Mentioned in:

Most Anticipated: The Great Winter 2025 Preview

It's cold, it's grey, its bleak—but winter, at the very least, brings with it a glut of anticipation-inducing books. Here you’ll find nearly 100 titles that we’re excited to cozy up with this season. Some we’ve already read in galley form; others we’re simply eager to devour based on their authors, subjects, or blurbs. We'd love for you to find your next great read among them.

The Millions will be taking a hiatus for the next few months, but we hope to see you soon.

—Sophia Stewart, editor

January

The Legend of Kumai by Shirato Sanpei, tr. Richard Rubinger (Drawn & Quarterly)

The epic 10-volume series, a touchstone of longform storytelling in manga now published in English for the first time, follows outsider Kamui in 17th-century Japan as he fights his way up from peasantry to the prized role of ninja. —Michael J. Seidlinger

The Life of Herod the Great by Zora Neale Hurston (Amistad)

In the years before her death in 1960, Hurston was at work on what she envisioned as a continuation of her 1939 novel, Moses, Man of the Mountain. Incomplete, nearly lost to fire, and now published for the first time alongside scholarship from editor Deborah G. Plant, Hurston’s final manuscript reimagines Herod, villain of the New Testament Gospel accounts, as a magnanimous and beloved leader of First Century Judea. —Jonathan Frey

Mood Machine by Liz Pelly (Atria)

When you eagerly posted your Spotify Wrapped last year, did you notice how much of what you listened to tended to sound... the same? Have you seen all those links to Bandcamp pages your musician friends keep desperately posting in the hopes that maybe, just maybe, you might give them money for their art? If so, this book is for you. —John H. Maher

My Country, Africa by Andrée Blouin (Verso)

African revolutionary Blouin recounts a radical life steeped in activism in this vital autobiography, from her beginnings in a colonial orphanage to her essential role in the continent's midcentury struggles for decolonization. —Sophia M. Stewart

The First and Last King of Haiti by Marlene L. Daut (Knopf)

Donald Trump repeatedly directs extraordinary animus towards Haiti and Haitians. This biography of Henry Christophe—the man who played a pivotal role in the Haitian Revolution—might help Americans understand why. —Claire Kirch

The Bewitched Bourgeois by Dino Buzzati, tr. Lawrence Venuti (NYRB)

This is the second story collection, and fifth book, by the absurdist-leaning midcentury Italian writer—whose primary preoccupation was war novels that blend the brutal with the fantastical—to get the NYRB treatment. May it not be the last. —JHM

Y2K by Colette Shade (Dey Street)

The recent Y2K revival mostly makes me feel old, but Shade's essay collection deftly illuminates how we got here, connecting the era's social and political upheavals to today. —SMS

Darkmotherland by Samrat Upadhyay (Penguin)

In a vast dystopian reimagining of Nepal, Upadhyay braids narratives of resistance (political, personal) and identity (individual, societal) against a backdrop of natural disaster and state violence. The first book in nearly a decade from the Whiting Award–winning author of Arresting God in Kathmandu, this is Upadhyay’s most ambitious yet. —JF

Metamorphosis by Ross Jeffery (Truborn)

From the author of I Died Too, But They Haven’t Buried Me Yet, a woman leads a double life as she loses her grip on reality by choice, wearing a mask that reflects her inner demons, as she descends into a hell designed to reveal the innermost depths of her grief-stricken psyche. —MJS

The Containment by Michelle Adams (FSG)

Legal scholar Adams charts the failure of desegregation in the American North through the story of the struggle to integrate suburban schools in Detroit, which remained almost completely segregated nearly two decades after Brown v. Board. —SMS

Death of the Author by Nnedi Okorafor (Morrow)

African Futurist Okorafor’s book-within-a-book offers interchangeable cover images, one for the story of a disabled, Black visionary in a near-present day and the other for the lead character’s speculative posthuman novel, Rusted Robots. Okorafor deftly keeps the alternating chapters and timelines in conversation with one another. —Nathalie op de Beeck

Open Socrates by Agnes Callard (Norton)

Practically everything Agnes Callard says or writes ushers in a capital-D Discourse. (Remember that profile?) If she can do the same with a study of the philosophical world’s original gadfly, culture will be better off for it. —JHM

Aflame by Pico Iyer (Riverhead)

Presumably he finds time to eat and sleep in there somewhere, but it certainly appears as if Iyer does nothing but travel and write. His latest, following 2023’s The Half Known Life, makes a case for the sublimity, and necessity, of silent reflection. —JHM

The In-Between Bookstore by Edward Underhill (Avon)

A local bookstore becomes a literal portal to the past for a trans man who returns to his hometown in search of a fresh start in Underhill's tender debut. —SMS

Good Girl by Aria Aber (Hogarth)

Aber, an accomplished poet, turns to prose with a debut novel set in the electric excess of Berlin’s bohemian nightlife scene, where a young German-born Afghan woman finds herself enthralled by an expat American novelist as her country—and, soon, her community—is enflamed by xenophobia. —JHM

The Orange Eats Creeps by Grace Krilanovich (Two Dollar Radio)

Krilanovich’s 2010 cult classic, about a runaway teen with drug-fueled ESP who searches for her missing sister across surreal highways while being chased by a killer named Dactyl, gets a much-deserved reissue. —MJS

Mona Acts Out by Mischa Berlinski (Liveright)

In the latest novel from the National Book Award finalist, a 50-something actress reevaluates her life and career when #MeToo allegations roil the off-off-Broadway Shakespearean company that has cast her in the role of Cleopatra. —SMS

Something Rotten by Andrew Lipstein (FSG)

A burnt-out couple leave New York City for what they hope will be a blissful summer in Denmark when their vacation derails after a close friend is diagnosed with a rare illness and their marriage is tested by toxic influences. —MJS

The Sun Won't Come Out Tomorrow by Kristen Martin (Bold Type)

Martin's debut is a cultural history of orphanhood in America, from the 1800s to today, interweaving personal narrative and archival research to upend the traditional "orphan narrative," from Oliver Twist to Annie. —SMS

We Do Not Part by Han Kang, tr. E. Yaewon and Paige Aniyah Morris (Hogarth)

Kang’s Nobel win last year surprised many, but the consistency of her talent certainly shouldn't now. The latest from the author of The Vegetarian—the haunting tale of a Korean woman who sets off to save her injured friend’s pet at her home in Jeju Island during a deadly snowstorm—will likely once again confront the horrors of history with clear eyes and clarion prose. —JHM

We Are Dreams in the Eternal Machine by Deni Ellis Béchard (Milkweed)

As the conversation around emerging technology skews increasingly to apocalyptic and utopian extremes, Béchard’s latest novel adopts the heterodox-to-everyone approach of embracing complexity. Here, a cadre of characters is isolated by a rogue but benevolent AI into controlled environments engineered to achieve their individual flourishing. The AI may have taken over, but it only wants to best for us. —JF

The Harder I Fight the More I Love You by Neko Case (Grand Central)

Singer-songwriter Case, a country- and folk-inflected indie rocker and sometime vocalist for the New Pornographers, takes her memoir’s title from her 2013 solo album. Followers of PNW music scene chronicles like Kathleen Hanna’s Rebel Girl and drummer Steve Moriarty’s Mia Zapata and the Gits will consider Case’s backstory a must-read. —NodB

The Loves of My Life by Edmund White (Bloomsbury)

The 85-year-old White recounts six decades of love and sex in this candid and erotic memoir, crafting a landmark work of queer history in the process. Seminal indeed. —SMS

Blob by Maggie Su (Harper)

In Su’s hilarious debut, Vi Liu is a college dropout working a job she hates, nothing really working out in her life, when she stumbles across a sentient blob that she begins to transform as her ideal, perfect man that just might resemble actor Ryan Gosling. —MJS

Sinkhole and Other Inexplicable Voids by Leyna Krow (Penguin)

Krow’s debut novel, Fire Season, traced the combustible destinies of three Northwest tricksters in the aftermath of an 1889 wildfire. In her second collection of short fiction, Krow amplifies surreal elements as she tells stories of ordinary lives. Her characters grapple with deadly viruses, climate change, and disasters of the Anthropocene’s wilderness. —NodB

Black in Blues by Imani Perry (Ecco)

The National Book Award winner—and one of today's most important thinkers—returns with a masterful meditation on the color blue and its role in Black history and culture. —SMS

Too Soon by Betty Shamieh (Avid)

The timely debut novel by Shamieh, a playwright, follows three generations of Palestinian American women as they navigate war, migration, motherhood, and creative ambition. —SMS

How to Talk About Love by Plato, tr. Armand D'Angour (Princeton UP)

With modern romance on its last legs, D'Angour revisits Plato's Symposium, mining the philosopher's masterwork for timeless, indispensable insights into love, sex, and attraction. —SMS

At Dark, I Become Loathsome by Eric LaRocca (Blackstone)

After Ashley Lutin’s wife dies, he takes the grieving process in a peculiar way, posting online, “If you're reading this, you've likely thought that the world would be a better place without you,” and proceeds to offer a strange ritual for those that respond to the line, equally grieving and lost, in need of transcendence. —MJS

February

No One Knows by Osamu Dazai, tr. Ralph McCarthy (New Directions)

A selection of stories translated in English for the first time, from across Dazai’s career, demonstrates his penchant for exploring conformity and society’s often impossible expectations of its members. —MJS

Mutual Interest by Olivia Wolfgang-Smith (Bloomsbury)

This queer love story set in post–Gilded Age New York, from the author of Glassworks (and one of my favorite Millions essays to date), explores on sex, power, and capitalism through the lives of three queer misfits. —SMS

Pure, Innocent Fun by Ira Madison III (Random House)

This podcaster and pop culture critic spoke to indie booksellers at a fall trade show I attended, regaling us with key cultural moments in the 1990s that shaped his youth in Milwaukee and being Black and gay. If the book is as clever and witty as Madison is, it's going to be a winner. —CK

Gliff by Ali Smith (Pantheon)

The Scottish author has been on the scene since 1997 but is best known today for a seasonal quartet from the late twenty-teens that began in 2016 with Autumn and ended in 2020 with Summer. Here, she takes the genre turn, setting two children and a horse loose in an authoritarian near future. —JHM

Land of Mirrors by Maria Medem, tr. Aleshia Jensen and Daniela Ortiz (D&Q)

This hypnotic graphic novel from one of Spain's most celebrated illustrators follows Antonia, the sole inhabitant of a deserted town, on a color-drenched quest to preserve the dying flower that gives her purpose. —SMS

Bibliophobia by Sarah Chihaya (Random House)

As odes to the "lifesaving power of books" proliferate amid growing literary censorship, Chihaya—a brilliant critic and writer—complicates this platitude in her revelatory memoir about living through books and the power of reading to, in the words of blurber Namwali Serpell, "wreck and redeem our lives." —SMS

Reading the Waves by Lidia Yuknavitch (Riverhead)

Yuknavitch continues the personal story she began in her 2011 memoir, The Chronology of Water. More than a decade after that book, and nearly undone by a history of trauma and the death of her daughter, Yuknavitch revisits the solace she finds in swimming (she was once an Olympic hopeful) and in her literary community. —NodB

The Dissenters by Youssef Rakha (Graywolf)

A son reevaluates the life of his Egyptian mother after her death in Rakha's novel. Recounting her sprawling life story—from her youth in 1960s Cairo to her experience of the 2011 Tahrir Square protests—a vivid portrait of faith, feminism, and contemporary Egypt emerges. —SMS

Tetra Nova by Sophia Terazawa (Deep Vellum)

Deep Vellum has a particularly keen eye for fiction in translation that borders on the unclassifiable. This debut from a poet the press has published twice, billed as the story of “an obscure Roman goddess who re-imagines herself as an assassin coming to terms with an emerging performance artist identity in the late-20th century,” seems right up that alley. —JHM

David Lynch's American Dreamscape by Mike Miley (Bloomsbury)

Miley puts David Lynch's films in conversation with literature and music, forging thrilling and unexpected connections—between Eraserhead and "The Yellow Wallpaper," Inland Empire and "mixtape aesthetics," Lynch and the work of Cormac McCarthy. Lynch devotees should run, not walk. —SMS

There's No Turning Back by Alba de Céspedes, tr. Ann Goldstein (Washington Square)

Goldstein is an indomitable translator. Without her, how would you read Ferrante? Here, she takes her pen to a work by the great Cuban-Italian writer de Céspedes, banned in the fascist Italy of the 1930s, that follows a group of female literature students living together in a Roman boarding house. —JHM

Beta Vulgaris by Margie Sarsfield (Norton)

Named for the humble beet plant and meaning, in a rough translation from the Latin, "vulgar second," Sarsfield’s surreal debut finds a seasonal harvest worker watching her boyfriend and other colleagues vanish amid “the menacing but enticing siren song of the beets.” —JHM

People From Oetimu by Felix Nesi, tr. Lara Norgaard (Archipelago)

The center of Nesi’s wide-ranging debut novel is a police station on the border between East and West Timor, where a group of men have gathered to watch the final of the 1998 World Cup while a political insurgency stirs without. Nesi, in English translation here for the first time, circles this moment broadly, reaching back to the various colonialist projects that have shaped Timor and the lives of his characters. —JF

Brother Brontë by Fernando A. Flores (MCD)

This surreal tale, set in a 2038 dystopian Texas is a celebration of resistance to authoritarianism, a mash-up of Olivia Butler, Ray Bradbury, and John Steinbeck. —CK

Alligator Tears by Edgar Gomez (Crown)

The High-Risk Homosexual author returns with a comic memoir-in-essays about fighting for survival in the Sunshine State, exploring his struggle with poverty through the lens of his queer, Latinx identity. —SMS

Theory & Practice by Michelle De Kretser (Catapult)

This lightly autofictional novel—De Krester's best yet, and one of my favorite books of this year—centers on a grad student's intellectual awakening, messy romantic entanglements, and fraught relationship with her mother as she minds the gap between studying feminist theory and living a feminist life. —SMS

The Lamb by Lucy Rose (Harper)

Rose’s cautionary and caustic folk tale is about a mother and daughter who live alone in the forest, quiet and tranquil except for the visitors the mother brings home, whom she calls “strays,” wining and dining them until they feast upon the bodies. —MJS

Disposable by Sarah Jones (Avid)

Jones, a senior writer for New York magazine, gives a voice to America's most vulnerable citizens, who were deeply and disproportionately harmed by the pandemic—a catastrophe that exposed the nation's disregard, if not outright contempt, for its underclass. —SMS

No Fault by Haley Mlotek (Viking)

Written in the aftermath of the author's divorce from the man she had been with for 12 years, this "Memoir of Romance and Divorce," per its subtitle, is a wise and distinctly modern accounting of the end of a marriage, and what it means on a personal, social, and literary level. —SMS

Enemy Feminisms by Sophie Lewis (Haymarket)

Lewis, one of the most interesting and provocative scholars working today, looks at certain malignant strains of feminism that have done more harm than good in her latest book. In the process, she probes the complexities of gender equality and offers an alternative vision of a feminist future. —SMS

Lion by Sonya Walger (NYRB)

Walger—an successful actor perhaps best known for her turn as Penny Widmore on Lost—debuts with a remarkably deft autobiographical novel (published by NYRB no less!) about her relationship with her complicated, charismatic Argentinian father. —SMS

The Voices of Adriana by Elvira Navarro, tr. Christina MacSweeney (Two Lines)

A Spanish writer and philosophy scholar grieves her mother and cares for her sick father in Navarro's innovative, metafictional novel. —SMS

Autotheories ed. Alex Brostoff and Vilashini Cooppan (MIT)

Theory wonks will love this rigorous and surprisingly playful survey of the genre of autotheory—which straddles autobiography and critical theory—with contributions from Judith Butler, Jamieson Webster, and more.

Fagin the Thief by Allison Epstein (Doubleday)

I enjoy retellings of classic novels by writers who turn the spotlight on interesting minor characters. This is an excursion into the world of Charles Dickens, told from the perspective iconic thief from Oliver Twist. —CK

Crush by Ada Calhoun (Viking)

Calhoun—the masterful memoirist behind the excellent Also A Poet—makes her first foray into fiction with a debut novel about marriage, sex, heartbreak, all-consuming desire. —SMS

Show Don't Tell by Curtis Sittenfeld (Random House)

Sittenfeld's observations in her writing are always clever, and this second collection of short fiction includes a tale about the main character in Prep, who visits her boarding school decades later for an alumni reunion. —CK

Right-Wing Woman by Andrea Dworkin (Picador)

One in a trio of Dworkin titles being reissued by Picador, this 1983 meditation on women and American conservatism strikes a troublingly resonant chord in the shadow of the recent election, which saw 45% of women vote for Trump. —SMS

The Talent by Daniel D'Addario (Scout)

If your favorite season is awards, the debut novel from D'Addario, chief correspondent at Variety, weaves an awards-season yarn centering on five stars competing for the Best Actress statue at the Oscars. If you know who Paloma Diamond is, you'll love this. —SMS

Death Takes Me by Cristina Rivera Garza, tr. Sarah Booker and Robin Myers (Hogarth)

The Pulitzer winner’s latest is about an eponymously named professor who discovers the body of a mutilated man with a bizarre poem left with the body, becoming entwined in the subsequent investigation as more bodies are found. —MJS

The Strange Case of Jane O. by Karen Thompson Walker (Random House)

Jane goes missing after a sudden a debilitating and dreadful wave of symptoms that include hallucinations, amnesia, and premonitions, calling into question the foundations of her life and reality, motherhood and buried trauma. —MJS

Song So Wild and Blue by Paul Lisicky (HarperOne)

If it weren’t Joni Mitchell’s world with all of us just living in it, one might be tempted to say the octagenarian master songstress is having a moment: this memoir of falling for the blue beauty of Mitchell’s work follows two other inventive books about her life and legacy: Ann Powers's Traveling and Henry Alford's I Dream of Joni. —JHM

Mornings Without Mii by Mayumi Inaba, tr. Ginny Tapley (FSG)

A woman writer meditates on solitude, art, and independence alongside her beloved cat in Inaba's modern classic—a book so squarely up my alley I'm somehow embarrassed. —SMS

True Failure by Alex Higley (Coffee House)

When Ben loses his job, he decides to pretend to go to work while instead auditioning for Big Shot, a popular reality TV show that he believes might be a launchpad for his future successes. —MJS

March

Woodworking by Emily St. James (Crooked Reads)

Those of us who have been reading St. James since the A.V. Club days may be surprised to see this marvelous critic's first novel—in this case, about a trans high school teacher befriending one of her students, the only fellow trans woman she’s ever met—but all the more excited for it. —JHM

Optional Practical Training by Shubha Sunder (Graywolf)

Told as a series of conversations, Sunder’s debut novel follows its recently graduated Indian protagonist in 2006 Cambridge, Mass., as she sees out her student visa teaching in a private high school and contriving to find her way between worlds that cannot seem to comprehend her. Quietly subversive, this is an immigration narrative to undermine the various reductionist immigration narratives of our moment. —JF

Love, Queenie by Mayukh Sen (Norton)

Merle Oberon, one of Hollywood's first South Asian movie stars, gets her due in this engrossing biography, which masterfully explores Oberon's painful upbringing, complicated racial identity, and much more. —SMS

The Age of Choice by Sophia Rosenfeld (Princeton UP)

At a time when we are awash with options—indeed, drowning in them—Rosenfeld's analysis of how our modingn idea of "freedom" became bound up in the idea of personal choice feels especially timely, touching on everything from politics to romance. —SMS

Sucker Punch by Scaachi Koul (St. Martin's)

One of the internet's funniest writers follows up One Day We'll All Be Dead and None of This Will Matter with a sharp and candid collection of essays that sees her life go into a tailspin during the pandemic, forcing her to reevaluate her beliefs about love, marriage, and what's really worth fighting for. —SMS

The Mysterious Disappearance of the Marquise of Loria by José Donoso, tr. Megan McDowell (New Directions)

The ever-excellent McDowell translates yet another work by the influential Chilean author for New Directions, proving once again that Donoso had a knack for titles: this one follows up 2024’s behemoth The Obscene Bird of Night. —JHM

Remember This by Anthony Giardina (FSG)

On its face, it’s another book about a writer living in Brooklyn. A layer deeper, it’s a book about fathers and daughters, occupations and vocations, ethos and pathos, failure and success. —JHM

Ultramarine by Mariette Navarro (Deep Vellum)

In this metaphysical and lyrical tale, a captain known for sticking to protocol begins losing control not only of her crew and ship but also her own mind. —MJS

We Tell Ourselves Stories by Alissa Wilkinson (Liveright)

Amid a spate of new books about Joan Didion published since her death in 2021, this entry by Wilkinson (one of my favorite critics working today) stands out for its approach, which centers Hollywood—and its meaning-making apparatus—as an essential key to understanding Didion's life and work. —SMS

Seven Social Movements that Changed America by Linda Gordon (Norton)

This book—by a truly renowned historian—about the power that ordinary citizens can wield when they organize to make their community a better place for all could not come at a better time. —CK

Mothers and Other Fictional Characters by Nicole Graev Lipson (Chronicle Prism)

Lipson reconsiders the narratives of womanhood that constrain our lives and imaginations, mining the canon for alternative visions of desire, motherhood, and more—from Kate Chopin and Gwendolyn Brooks to Philip Roth and Shakespeare—to forge a new story for her life. —SMS

Goddess Complex by Sanjena Sathian (Penguin)

Doppelgängers have been done to death, but Sathian's examination of Millennial womanhood—part biting satire, part twisty thriller—breathes new life into the trope while probing the modern realities of procreation, pregnancy, and parenting. —SMS

Stag Dance by Torrey Peters (Random House)

The author of Detransition, Baby offers four tales for the price of one: a novel and three stories that promise to put gender in the crosshairs with as sharp a style and swagger as Peters’ beloved latest. The novel even has crossdressing lumberjacks. —JHM

On Breathing by Jamieson Webster (Catapult)

Webster, a practicing psychoanalyst and a brilliant writer to boot, explores that most basic human function—breathing—to address questions of care and interdependence in an age of catastrophe. —SMS

Unusual Fragments: Japanese Stories (Two Lines)

The stories of Unusual Fragments, including work by Yoshida Tomoko, Nobuko Takai, and other seldom translated writers from the same ranks as Abe and Dazai, comb through themes like alienation and loneliness, from a storm chaser entering the eye of a storm to a medical student observing a body as it is contorted into increasingly violent positions. —MJS

The Antidote by Karen Russell (Knopf)

Russell has quipped that this Dust Bowl story of uncanny happenings in Nebraska is the “drylandia” to her 2011 Florida novel, Swamplandia! In this suspenseful account, a woman working as a so-called prairie witch serves as a storage vault for her townspeople’s most troubled memories of migration and Indigenous genocide. With a murderer on the loose, a corrupt sheriff handling the investigation, and a Black New Deal photographer passing through to document Americana, the witch loses her memory and supernatural events parallel the area’s lethal dust storms. —NodB

On the Clock by Claire Baglin, tr. Jordan Stump (New Directions)

Baglin's bildungsroman, translated from the French, probes the indignities of poverty and service work from the vantage point of its 20-year-old narrator, who works at a fast-food joint and recalls memories of her working-class upbringing. —SMS

Motherdom by Alex Bollen (Verso)

Parenting is difficult enough without dealing with myths of what it means to be a good mother. I who often felt like a failure as a mother appreciate Bollen's focus on a more realistic approach to parenting. —CK

The Magic Books by Anne Lawrence-Mathers (Yale UP)

For that friend who wants to concoct the alchemical elixir of life, or the person who cannot quit Susanna Clark’s Jonathan Strange and Mr. Norrell, Lawrence-Mathers collects 20 illuminated medieval manuscripts devoted to magical enterprise. Her compendium includes European volumes on astronomy, magical training, and the imagined intersection between science and the supernatural. —NodB

Theft by Abdulrazak Gurnah (Riverhead)

The first novel by the Tanzanian-British Nobel laureate since his surprise win in 2021 is a story of class, seismic cultural change, and three young people in a small Tanzania town, caught up in both as their lives dramatically intertwine. —JHM

Twelve Stories by American Women, ed. Arielle Zibrak (Penguin Classics)

Zibrak, author of a delicious volume on guilty pleasures (and a great essay here at The Millions), curates a dozen short stories by women writers who have long been left out of American literary canon—most of them women of color—from Frances Ellen Watkins Harper to Zitkala-Ša. —SMS

I'll Love You Forever by Giaae Kwon (Holt)

K-pop’s sky-high place in the fandom landscape made a serious critical assessment inevitable. This one blends cultural criticism with memoir, using major artists and their careers as a lens through which to view the contemporary Korean sociocultural landscape writ large. —JHM

The Buffalo Hunter Hunter by Stephen Graham Jones (Saga)

Jones, the acclaimed author of The Only Good Indians and the Indian Lake Trilogy, offers a unique tale of historical horror, a revenge tale about a vampire descending upon the Blackfeet reservation and the manifold of carnage in their midst. —MJS

True Mistakes by Lena Moses-Schmitt (University of Arkansas Press)

Full disclosure: Lena is my friend. But part of why I wanted to be her friend in the first place is because she is a brilliant poet. Selected by Patricia Smith as a finalist for the Miller Williams Poetry Prize, and blurbed by the great Heather Christle and Elisa Gabbert, this debut collection seeks to turn "mistakes" into sites of possibility. —SMS

Perfection by Vicenzo Latronico, tr. Sophie Hughes (NYRB)

Anna and Tom are expats living in Berlin enjoying their freedom as digital nomads, cultivating their passion for capturing perfect images, but after both friends and time itself moves on, their own pocket of creative freedom turns boredom, their life trajectories cast in doubt. —MJS

Guatemalan Rhapsody by Jared Lemus (Ecco)

Jemus's debut story collection paint a composite portrait of the people who call Guatemala home—and those who have left it behind—with a cast of characters that includes a medicine man, a custodian at an underfunded college, wannabe tattoo artists, four orphaned brothers, and many more.

Pacific Circuit by Alexis Madrigal (MCD)

The Oakland, Calif.–based contributing writer for the Atlantic digs deep into the recent history of a city long under-appreciated and under-served that has undergone head-turning changes throughout the rise of Silicon Valley. —JHM

Barbara by Joni Murphy (Astra)

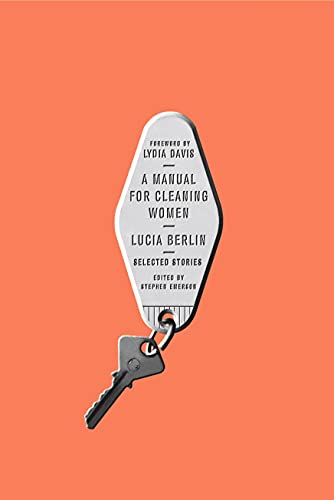

Described as "Oppenheimer by way of Lucia Berlin," Murphy's character study follows the titular starlet as she navigates the twinned convulsions of Hollywood and history in the Atomic Age.

Sister Sinner by Claire Hoffman (FSG)

This biography of the fascinating Aimee Semple McPherson, America's most famous evangelist, takes religion, fame, and power as its subjects alongside McPherson, whose life was suffused with mystery and scandal. —SMS

Trauma Plot by Jamie Hood (Pantheon)

In this bold and layered memoir, Hood confronts three decades of sexual violence and searches for truth among the wreckage. Kate Zambreno calls Trauma Plot the work of "an American Annie Ernaux." —SMS

Hey You Assholes by Kyle Seibel (Clash)

Seibel’s debut story collection ranges widely from the down-and-out to the downright bizarre as he examines with heart and empathy the strife and struggle of his characters. —MJS

James Baldwin by Magdalena J. Zaborowska (Yale UP)

Zaborowska examines Baldwin's unpublished papers and his material legacy (e.g. his home in France) to probe about the great writer's life and work, as well as the emergence of the "Black queer humanism" that Baldwin espoused. —CK

Stop Me If You've Heard This One by Kristen Arnett (Riverhead)

Arnett is always brilliant and this novel about the relationship between Cherry, a professional clown, and her magician mentor, "Margot the Magnificent," provides a fascinating glimpse of the unconventional lives of performance artists. —CK

Paradise Logic by Sophie Kemp (S&S)

The deal announcement describes the ever-punchy writer’s debut novel with an infinitely appealing appellation: “debauched picaresque.” If that’s not enough to draw you in, the truly unhinged cover should be. —JHM

[millions_email]

A Year in Reading: 2024

Welcome to the 20th (!) installment of The Millions' annual Year in Reading series, which gathers together some of today's most exciting writers and thinkers to share the books that shaped their year. YIR is not a collection of yearend best-of lists; think of it, perhaps, as an assemblage of annotated bibliographies. We've invited contributors to reflect on the books they read this year—an intentionally vague prompt—and encouraged them to approach the assignment however they choose.

In writing about our reading lives, as YIR contributors are asked to do, we inevitably write about our personal lives, our inner lives. This year, a number of contributors read their way through profound grief and serious illness, through new parenthood and cross-country moves. Some found escape in frothy romances, mooring in works of theology, comfort in ancient epic poetry. More than one turned to the wisdom of Ursula K. Le Guin. Many describe a book finding them just when they needed it.

Interpretations of the assignment were wonderfully varied. One contributor, a music critic, considered the musical analogs to the books she read, while another mapped her reads from this year onto constellations. Most people's reading was guided purely by pleasure, or else a desire to better understand events unfolding in their lives or larger the world. Yet others centered their reading around a certain sense of duty: this year one contributor committed to finishing the six Philip Roth novels he had yet to read, an undertaking that he likens to “eating a six-pack of paper towels.” (Lucky for us, he included in his essay his final ranking of Roth's oeuvre.)

The books that populate these essays range widely, though the most commonly noted title this year was Tony Tulathimutte’s story collection Rejection. The work of newly minted National Book Award winner Percival Everett, particularly his acclaimed novel James, was also widely read and written about. And as the genocide of Palestinians in Gaza enters its second year, many contributors sought out Isabella Hammad’s searing, clear-eyed essay Recognizing the Stranger.

Like so many endeavors in our chronically under-resourced literary community, Year in Reading is a labor of love. The Millions is a one-person editorial operation (with an invaluable assist from SEO maven Dani Fishman), and producing YIR—and witnessing the joy it brings contributors and readers alike—has been the highlight of my tenure as editor. I’m profoundly grateful for the generosity of this year’s contributors, whose names and entries will be revealed below over the next three weeks, concluding on Wednesday, December 18. Be sure to subscribe to The Millions’ free newsletter to get the week’s entries sent straight to your inbox each Friday.

—Sophia Stewart, editor

Becca Rothfeld, author of All Things Are Too Small

Carvell Wallace, author of Another Word for Love

Charlotte Shane, author of An Honest Woman

Brianna Di Monda, writer and editor

Nell Irvin Painter, author of I Just Keep Talking

Carrie Courogen, author of Miss May Does Not Exist

Ayşegül Savaş, author of The Anthropologists

Zachary Issenberg, writer

Tony Tulathimutte, author of Rejection

Ann Powers, author of Traveling: On the Path of Joni Mitchell

Lidia Yuknavitch, author of Reading the Waves

Nicholas Russell, writer and critic

Daniel Saldaña París, author of Planes Flying Over a Monster

Lili Anolik, author of Didion and Babitz

Deborah Ghim, editor

Emily Witt, author of Health and Safety

Nathan Thrall, author of A Day in the Life of Abed Salama

Lena Moses-Schmitt, author of True Mistakes

Jeremy Gordon, author of See Friendship

John Lee Clark, author of Touch the Future

Ellen Wayland-Smith, author of The Science of Last Things

Edwin Frank, publisher and author of Stranger Than Fiction

Sophia Stewart, editor of The Millions

A Year in Reading Archives: 2023, 2022, 2021, 2020, 2019, 2018, 2017, 2016, 2015, 2014, 2013, 2011, 2010, 2009, 2008, 2007, 2006, 2005

In Order to Live: Story Structure in the Horoscopic Style

In the late 12th century, the father of teenage Leonardo Fibonacci takes him off the North African streets and sets him at the feet of gruff Arab tutors. They can’t help it -- they like the kid, who they can tell is going to be a nightmare until they agree to teach him the Art of Nine Symbols. Back in Pisa, Fibonacci discovers an axiomatic sequence in which each number is the sum of the two preceding numbers (1, 1, 2, 3, 5, 8, 13, 21). The corresponding ratio describes the pleasing spiral he’s been staring at all day -- it just looks right. Eight hundred years later, a creative-writing student drafting a story is told it might help to draw its plot. And there it is. (See figure A.)

Structure

Here come the metaphors. John McPhee compares writing a story to prepping a meal, and to the gathering -- crystallizing -- of salt underground. His essay, “Structure,” traces the Continental Divide, pulls on “chronological drawstrings,” and knits the presumed narrative scarf from the “threads” everyone keeps talking about. McPhee encourages students to diagram a story as “a horizontal line with loops above and below it to represent the tangents along the storyline, a circle with lines shooting out of it that denote narrative pathways…” (See Figure B.) The rhetorical free-for-all disguises the wide influence of the gist -- the anatomy of storytelling. Speaking of stories, “the shape of the curve is what matters,” says Kurt Vonnegut. Whereas Gustav Freytag’s muse was, sadly, a triangle, the sign and symbol of Fibonacci-McPhee is more like a map. But they’re manifestations of the same idea: of stories seeking, building, bending like a river, or anyways conceived of less as an appeal to a reader than as science-ish fieldwork. This definition of structure -- indeed any definition of it -- begs the question: What if structure is not that geometric or quite so cosmic or even, according to an au courant diagnosis, “televisual?” What if structure consists of questions themselves and not strictly the objects of those questions with which plotting is synonymous: A dead body. An excess of suitors. “A fully armed and operational battle station.”

Stories posit a teller in the service of the told, who are now able to, if they must, rate that service with a fractional number of stars. But the novel especially is a kind of hopeless democracy of two. An author and a reader staring at the same machine -- the same story -- not sure if and when it worked. Two privileged children -- serialized TV and narrative nonfiction -- have done so well for themselves that they should have laid the framework bare. But an erudite incoherence about structure is the rule. One thing for sure is that structure’s an anxiety, about a better way to tell a story, and surer proof of our discernment -- that we get it. And so the idea of order in nature settles the nerves. The golden spiral is in the leaves, in shells -- in stories?

The Fibonacci-McPhee Sequence

Early on in Garth Risk Hallberg’s City on Fire there’s a transition in point of view, from William -- scion, dilettante, and ex-singer in a punk band -- to a blank-slate teen, Charlie, as he removes from its sleeve “the first Ex Post Facto LP from ’74.” This raised my hackles -- though perhaps I should admit to having the quick-trigger hackles of someone with too many bookmarks in too many novels, not to mention paused places in the middle of episode three of season two, etc. Along with the ambitious size of the book, the coincidences of City on Fire have been well scrutinized: “…overstuffed with characters, and the lines of action uniting them fray to the point of breaking;” “overuse of chance discoveries of buried evidence.” There’s a wariness about what exactly the novel’s up to, despite the fact that just a little later it more or less tells you. In what is either a cool nod to, or a hearty embrace of, genre convention, Charlie’s crush, Samantha Cicciaro, is mysteriously shot. But thereafter the book occupies itself less with whodunit than with the shots’ sound waves ringing out into the night, washing over 10 other characters and, in a quantum-mechanical whisper, telling them that no one is alone.

City on Fire is a needle threaded between conventional plotting and ambitious “structure.” It finds itself among contemporary novels exhibiting an inflated sense of connection -- storytelling in a kind of horoscopic style. It’s always been an odd thing to chalk up to a matter of belief: that one reader’s definition of a story is to another not a story at all. In a twist you would have never seen coming, “narrative architecture” becomes our term for what’s not necessarily there.

In time, those Unconscionable Maps no longer satisfied, and the Cartographers Guilds struck a Map of the Empire whose size was that of the Empire, and which coincided point for point with it.

-- Jorge Luis Borges, “On Exactitude in Science”

We have no idea what we’re talking about when we talk about structure. The following terms were used to describe the structure of narratives bearing the mark of horoscopic style (David Mitchell’s Cloud Atlas, Jennifer Egan’s A Visit from the Goon Squad, City on Fire, and David Benioff and D.B. Weiss’s TV adaptation Game of Thrones): “stereoscopic,” “televisual,” “kaleidoscopic,” “unfilmable” -- at least before the film. These structures were “non-linear,” “multi-head,” “multi-thread,” “rhizomatic,” “fragmented” -- this last appearing so often that I had to wonder just what constitutes whole, homogeneous storytelling. What was it about these structures that was so “innovative” and “experimental?” Or, for that matter, “soap operatic” and “ruthless?”

To wit, Cloud Atlas is defined by “mapping” and “maplessness.” Its structure is “cool.” Here’s what happens: The novel’s five story lines culminate palindromically in one central section before the stories pick up in reverse order in the second half of the book (A, B, C, D, E, F, E, D, C, B, A). But that’s not what’s happening. Circumstantially, the story lines are connected by a birthmark, and, thematically, by music. The Five Narratives are also connected by the fact that Mitchell wrote them impeccably and, in accordance with genre, faithfully. It is said that the author pulled it off by “immersing himself in the different narratives one at a time, even keeping them in different ‘folders.’” Here is structure conflated with something more like process -- the scout’s knot tying oneself to a chair. The story is a function of the author’s method of organizing for himself. McPhee describes his own use of Nabokovian note cards: “Then I move the cards around to see where I’m going to find a good structure, a legitimate structure.” It seems fair to ask: Who’s immersing whom here? Shall we perhaps hold each part of the story and think about whether or not it brings us joy?

These are the perils of “world-building.” A Game of Thrones episode marks time by cutting to each of its story lines, from Winterfell to Meereen, ne’er betraying a particular imperative to move the story in any direction but between. There’s a similar call-sheet structure to A Visit from the Goon Squad (the aforementioned rhizome); in her review, Sarah Churchwell sums up horoscopic style quite nicely:

Egan’s vision of history and time is also decidedly, and perhaps reassuringly, cyclical: the impacts these characters have upon each other are engineered not by coincidence but by connectedness itself, as the people we bump against and bang into become the story of our lives.

Not coincidentally, here is how Hallberg describes his intrepid journalist character: “A receiver. A connector. A machine made exactly for this.” Let us remember our Borges: that absolutely accurate “Map of the Empire” is torn to faded shreds, except, perhaps, where it showed us those places we’d put down our novels. Granted, these books are in almost every way excellent; Egan, Mitchell, and Hallberg are genius naturalists. Capable of invoking anything -- any clipper ship or anxiety or rhododendron. But that kind of genius can be difficult to distinguish from a painterly need to get into the corners of the frame. Structure should be instrumental to a thing’s use; a handle for the writer’s talent. And yet the imperial cartographer’s exactitude somehow became a suitable answer for how to keep a reader in thrall. These novels have been praised for, among other things, ambition, inventiveness, and that they are, but what connects them more than anything else is that they’re romantic about structure.

The least we could do is to stop insisting that we’re all referring to the same thing. Which is, generally, convention. Structure is nearly synonymous with aiming for the cheap seats of genre, where the detective and the wizard and the submissive sit together and watch the game. We’ve come to regard suspense as a market force -- an outline in chalk with which to take ingenious exception. And so we’re flush with cool hybrids. MacArthur fellows take on zombies; Ursula K. Le Guin gatekeeping Kazuo Ishiguro; a market for post-apocalypse in full bloom. But whenever much attention is paid to exceptions to the rule, one can only assume the rules are very clear. I’m speaking of genre, but also rent. Writing to market or furiously curating a social media platform are seen as considerations on the level of food on the table. A cottage industry in semi-pro writing has met popular -- and extremely earnest -- demand. In this sense, horoscopic style is both product and allergy to the “tools” of the craft industry; links to a “weak verb converter;” intensive three-day seminars for the low, low price of $995 for tuition and Final Draft software.

If our entertainments were piles of San Andrean rubble, wouldn’t we know? Perhaps, but structure has a way of passing itself off as an answer to the very question it presents -- it’s what works. “You can build a structure in such a way that it causes people to want to keep turning pages,” McPhee writes. And the other way?

“Listeners, we are currently fielding numerous reports that books have stopped working.”

-- Welcome to Night Vale, “Station Management”

“Fiction is the posing of narrative questions,” is actually something the writer David Lipsky has said aloud on multiple occasions. Lipsky teaches a class of singular usefulness, from which I basically repeat back lessons in a dazed monotone. Men call him Lipsky, and women call him David. We were of one mind to get a good seat, and another to duck and scribble. In class, Lipsky calls on people, a barbaric pedagogic practice literally frowned upon by most of us, and what’s more, there was a preponderance of correct answers -- never a drawing. The idea was that story -- or, synonymously -- structure, is no more and no less than to ask the reader leading questions in the hopes of interesting them. Of a given character -- will she or won’t she be fired, loved, caught, absolved? In the end, the class was approximately half Immunes, with the other half wearing white smocks sporting one of David’s terms of art printed in bold: withheld data.

No one likes to be asked what the story’s about. But Lipsky was never referring to the about of the abstract painting or the period of the historical novel. Nothing was an allegory of post-whatsit America. He meant: a girl is trying to fit in at a private school. Or: those letters were forged. And once the story’s little knife is stowed, and a quorum had nodded or squinted or furrowed, he would say ask us to make an annotation in the margin: If a particular story, once begun, should find itself resolved, another story has to take the baton.

Now and then I’ll read a novel by a writer who seems to have bought in. Lauren Groff’s Fates and Furies is a novel in two -- the technical term here would be “parts.” Groff sets up the reader for any number of things -- matriarchs withholding approval; a million-dollar bet on the marriage of an implausibly successful playwright to an “Ice queen from nowhere.” Readers will note the use of brackets. Nowhere-ian royalty Mathilde is “pretending to be faithful. [perhaps not].” Groff has referred to these bracketed asides as a “Greek chorus,” but what they are really is an efficient method of opening up dramatic-ironic gaps -- questions. “She couldn’t know, he thought. [She did!]”

Ironically it’s the alternatives to “narrative architecture” that can seem a little bloodless and technical. Structure, to George Saunders, consists of “tools with which to make your audience feel more deeply.” These being tools at anyone’s disposal, no matter how inconveniently literary. After all, there are high stakes in life as it is ordinarily lived, which is to say, pitched anxiously between desire and embarrassment. A story that works makes room for the possibility that it won’t. “It wouldn’t have to be good,” says the imperious, soon-wedded older sister in Rebecca Curtis’s “The Toast.” It just “needs to be appropriate.” And yet there are some of us who wouldn’t be caught dead using a “tool.” We might keep it in the drawer by the bed, but what writer told to tell their story, find their own voice -- “in order to live” -- would want to feed it through “clunky machinery.”

Who Cares? Case Studies

About Star Wars: The Force Awakens, critics had 8, 10, 11, 18, 32, 43, and 77 “questions,” 6 of which were of the “big” variety, 11 of which were size “huge.” And 7, 15, 17, and 25 questions had gone exasperatingly “Unanswered.” Question in this context means “plot hole,” of which 5, 9, 40 (and “20 more” on top of that) were “unforgivable.” Admittedly, some of the enumerated are more like inconsistencies -- does one need a map to reach coordinates in space? -- but many of these questions are entirely intentional plot devices. Where is Luke Skywalker? gets you the movie. Rey’s parentage gets you all three. To be clear, the notable equivalence here is between functional storytelling and the galling lack thereof. It’s hard to say just how this happens, but there might be a clue on the white smock, a variation on the lover’s quarrel: What’s the difference between not telling and a lie?

One more case study from the relevant world: Serial. When it became clear that a radio documentary had become a blockbuster, that people loved this murder, Sarah Koenig, it seems, felt herself painted into an ethical corner. Here she is, bristling at the notion of enacting “suspense,” with the NYT Magazine’s question in bold:

But the podcast is a hybrid of journalism and entertainment. You have a lot of information, and it seems you’ve structured it for maximum suspense. I don’t think that’s fair…To us, it didn’t feel that different from a really long magazine story or -- you know, any story that you would take care in structuring.

In the very first episode, Koenig describes Adnan Syed ’s mild manner -- he doesn’t seem like a vicious psychopath. “I know, I’m an idiot,” says Koenig, her tone pitched to effective self-deprecation. Koenig knows that 12 podcast episodes won’t decide whether in fact evil is human or inhuman. (Not even Janet Malcolm knows: “The concept of the psychopath is, in fact, an admission of failure to solve the mystery of evil -- it is merely a restatement of the mystery.”)

If not “suspense,” Koenig admits to “structuring.” But this distinction doesn’t hold up to scrutiny -- not that I question whatsoever Koenig’s integrity. Actually, Serial is too good, and too intelligently structured for her to have a leg to stand on. “I’m an idiot” is a play for identification. (“Silly me.” -- Season Two.) This line -- about looking into Adnan’s big brown eyes -- is right there in the script where, perhaps, there could have been a breakdown of cell-phone tower data (and after a useful delay of an episode or two, a questioning of its accuracy). I have little doubt about which was the better choice. When David Remnick asks Koenig about her method, she says, “I think I’m trying to convey that you can trust me because I’ve done my homework.” And in this sentiment, she sounds a lot like David Lipsky (“Bond with your reader. Tell them honest things.”). This trust is also a kind of structuring -- I know, I’m an idiot. But there are a lot of stories out there, and we tend to pick the one that looks us in the eye and asks, maybe a little preposterously, Can I tell you a secret?

Koenig is then asked about decisions she made with Serial’s decidedly unpatented voice. Co-producer Julie Snyder levels with her after an unsatisfying cut:

Edit after edit after edit…“It’s not working…It’s not good. I need to know what you -- Sarah Koenig -- make of all this. Otherwise I don’t care. I don’t know why you’re telling me all this...You need to make me care.” I was quite uncomfortable with that initially, but then I realized…That’s the thing that’s going to make you listen to the stuff I think is important.

If that sounds a lot like “Keep your eye on the ball,” you’re not wrong. But rest assured that our culture-making class hadn’t even thought of the ball much less kept an eye on it. (See: testaments to their confidence approximately everywhere you look.) Koenig’s discomforted by the idea that making someone else care is indistinguishable from selling it to them. To name just a few of the principled stands against Caring What Anyone Else Thinks: morning pages and the art-therapy discipline; The Compulsive’s Way -- simply not being able to stop; “Dance Like Nobody’s Watching,” or art as vocation (“I have gained a space of my own, a space that is free, where I feel active and present.” -- Elena Ferrante, not on Twitter). This has to do with one’s basic orientation as an author: Is art a means to cultivate or to reach? And if you must insist on writing, I have to ask -- just how acutely do you feel the need to be borne witness to? Because a singular question harries stories at every turn, echoing the unminced words at the Serial editing bay: What is any of this for? Inevitably, the answer occurs somewhat too late: Making someone else care is the highest commandment of structure.

Which is why, after the remedial instruction, almost all of what David Lipsky does is prose tips. The theory being that thinking unapologetically in terms of setting things up and paying them off frees the writer to devote themselves otherwise to sentence-making. The syllabus, with few exceptions, is composed of those writers who can really launch ships prose-wise: David Foster Wallace, Lorrie Moore, Vladimir Nabokov, Zadie Smith. In fact, the “system” -- would that it were my own batch of Kool-Aid -- kinda dead-ends at despairingly scintillating talent.

But generally speaking that talent is not responsible for America’s mass-market mysteries on short flights; or that which manages to hit her dull and chipped funny bone; or sate her great appetite for vanilla S&M and truer detectives. A working fallacy results. Tent poles such as Game of Thrones, The Marvel Universe -- they have a kind of ideological monopoly on What happens next? But the more we accept the premise that what succeeds in the market works, the easier it is to convince ourselves that the market itself strives to give us the culture we need. [It doesn’t.] The challenge for lit is the same for our culture at large from here on: distinguishing the market’s products from actual voices.

“Implausibility is part of the design.”

-- Louis Menand, “The Time of Broken Windows”

It’s not that Hallberg commits the ordinary fictional sin of superimposing a false meaning on his novel, which is ultimately just as believable as a line drawn to connect any one thing to another. City on Fire may be elaborately plotted, and a story richly told, but it is not given, not structured for us. Though, we can easily exaggerate the author’s sacrifice. It’s not quite walking in front of a tank; maybe more like picking up a shift. A sense of the uncanny, of a kind of empathic genius at work, is as essential an aspect of reading as structure, but most readers, I think, experience design as unforeseen plausibility.

Some things do work every time. For example, I go to the physical bookstore and get the “ambitious” book over and over, like Charlie Brown when Lucy promises to hold the football but instead of a football it’s that thing when The Times runs a review by Michiko Kakutani in the daily and then another on Sunday. Tour de force in hand, I go home and read the first chapter with a sheepish sense of my own demography. Along those lines, I can imagine how refining the concept of narrative structure must seem a split-hair, just another narcissistically small difference. Dirty tomatoes and organic stories at $26/lb -- not those factory-farm stories wrapped in pink blood on a bed of Styrofoam. But in the bathwater of authenticity are plenty of real distinctions -- I’m looking at you, Texas barbecue, starting a band, and the notion of a high literature that tells “honest things.” Whenever I hear that triumphalism -- lines grayed, blurred away! -- I find myself fondly missing the clarity of differences.

If you divide ten thousand by forty-one, you get two hundred and forty-three, which is Cascadia’s recurrence interval...That timespan is dangerous both because it is too long -- long enough for us to unwittingly build an entire civilization on top of our continent’s worst fault line -- and because it is not long enough.

-- Kathryn Schulz, “The Really Big One”

This is where it seems as if I should offer some kind of agnostic politesse. Endorse a descriptivism of storytelling -- all structures are “legitimate.” Any structure that makes you happy. “You don’t choose it so much as it chooses you,” says Carmine Cicciaro, Samantha’s father. It’s always tempting to side with anti-dogmatism. But I can’t do that. Because, what if there is a moral to this story?

Structure abides. Ex Machina’s key cards and power-outs; Groff’s unreliable Rashomon-esque narrators of sex after marriage. An out-of-print novelist sees a picture of Britney Spears exiting a restaurant holding a pack of cigarettes, her phone, “and then she’s got my second book.” (“Case #2: Britney”– Mystery Show.)

But it is literary reporting that has pretty much become structure’s standard bearer. In Rachel Aviv’s “Where Is your Mother?”, a healthy child cries in an empty apartment, and dust plumes off the bed. “I was born overseas,” the mother says, and nothing else. In “The Strange Case of Anna Stubblefield,” Daniel Engber asks “What if D.J. had a private chamber in his head, a place where grown-up thoughts were trapped behind his palsy?” Story writes itself, as they say. [Nope.] Then again, a sound almost like clockwork accompanies Kathryn Schulz writing of sixth-century tsunamis, barking dogs ahead of the wave, and a number: 243. In the first few paragraphs of these stories, it feels as if inspiration taken from McPhee’s looping squiggles was only ever as important as his old-hand assurance that the storytelling principle is ethically OK in “narrative nonfiction” or where’s-the-line journalism.

I’m not so worried about some moralizing theory of declining attentions spans -- our “distraction.” In fact, nothing could distract me from another form of anxiety: I desperately want to pay relentless attention to only the few, mattering things. Structure, truly evident, directs that attention. If stories are a means to tell us what you “think is important,” then by all means.

The policy of bracing honesty has these lesser known clauses: that you have to figure out what most needs to be said, and why anyone should want to hear you say it. If you happen to read pop physics, there’s what’s called the “observer effect.” Any observation affects the experiment (the “collapse of the wave function” -- what happens emerges from a prior limbo of possibilities). The observer effect also applies to the question of structure and the black box of process: none of it works, because it cannot be verifiably shown to have done what it intended to do. Writing is nothing until the precise moment the reader intuits a meaning. I want to tell you something. I can draw the map. Only you can tell me if it goes anywhere. Say the word.

Judging Books by Their Covers 2016: US vs. UK

The London Book Fair starts on April 12th. As a kick off, we thought it would be fun to compare the U.S. and U.K. covers of a few notable titles from last year, a task previously taken on by our much-loved outgoing editor, Mr. Max Magee.

I've lived in both the U.S. and the U.K. and always felt that if I could pinpoint the reason why the soap operas are so different -- the kleenex-lensed, pearly hues of The Young and the Restless vs. the gruff, flattened grays of East Enders as one example -- or articulate why marmite sandwiches appeal in one place when peanut butter and jelly is preferred in the other, I would finally understand where the two cultures divide.

Sometimes I look to book covers in an attempt for clarity. Why is a cover in the U.S. replaced with another in the U.K. when the words inside are exactly the same? I may not like marmite, but I do have a taste for books. I sat down to see if I could finally develop the overarching theory that has eluded me so far.

It's notable that many covers are the same. Some of the biggest books, like Helen Macdonald's H is for Hawk, Ta-Nehisi Coates's Between The World And Me, and Elena Ferrante's Neapolitan novels sport the same jackets in the U.S. and U.K. "It often comes down to differences in cultures and tastes. What appeals to people in one country doesn't appeal to others," says my literary agent, Denise Bukowski. "But if the book has been published first in one country and has been successful there, subsequent publishers often choose to capitalize on that success by using the original cover."

But many others titles still have completely different covers, which is fortunate as it means there is still plenty for us to argue about.

Below I present just a few of the choice examples. U.S. covers are on the left. U.K. covers are on the right. Your equally inexpert analysis, baseless opinions, and sweeping generalizations are encouraged in the comments.

Fates and Furies by Lauren Groff

These covers are intriguingly similar and yet so different. Swirls vs. angles, blues vs. reds, swishes vs. swipes, almost like a mirror of the two halves of the book, the first told by the husband, Lotto, and the second by the wife, Mathilde. I had trouble making sense of it all until I consulted an article called "How to Use Color Psychology to Give Your Business an Edge" and understood that there is subliminal messaging at work. The U.S. cover designer is on team Lotto and emphasized blue for grief, sadness, and distraction. In the U.K., the designer was on Mathilde's side, hence anger, rage, and ecstasy.

Hausfrau by Jill Alexander Essbaum

I love the U.S. cover for this book, but how does it relate to the story? Flowers are sex organs. This book is about sex organs. Then what of the U.K. cover -- embroidery is about not having sex. Or not messy sex. Maybe strictly missionary? Or if you get up to more, you have to make the bed perfectly afterwards, including carefully smoothing the bedspread so that no one will suspect what you've been up to. Which is exactly what this book is about.

The Girl on the Train by Paula Hawkins

These two covers clearly illustrate one big difference between the two countries, their respective outlooks on the events leading up to the U.S. presidential election. If you are a drunk woman in the U.S., the primaries feel like you are on a train and with all the antics, both comic and tragic, hurtling around you in an incomprehensible blur. If you are a drunk woman in the U.K., you watch from the outside and find yourself unable to take your wavering eyes off the speeding train -- the question that holds your attention is not if it will crash, but how.

Purity by Jonathan Franzen

Only a fool would think these covers came from different countries. They were clearly designed in alternate dimensions.

Did You Ever Have a Family by Bill Clegg

Both designs take inspiration from the publisher's description of the inciting incident: "This book of dark secrets opens with a blaze." However each seem to have decided that a different element of that incident is more enticing. In the U.S., readers might like dark, mildewy, water-damaged secrets, whereas in the U.K., a good house fire will make the book fly off the shelves?

A Little Life by Hanya Yanagihara

It's hard for me to imagine A Little Life without the ecstasy and agony conveyed by the iconic photograph on the U.S. edition, Orgasmic Man by Peter Hujar. I was struck by ecstasy every time I picked up this book and collapsed into agony after each reading session. I understand the reasoning behind the U.K. cover; it makes sense to put forward an image that evokes life in New York, but it doesn't echo the experience in the writing, as does Hujar's art. I wonder, are orgasms not a universal experience? Perhaps people in the U.K. do not have them.

Go Set a Watchman by Harper Lee

Finally, the clarity I seek. This one is straightforward. The U.S. cover lets you know the name of the book you are buying. The U.K. cover lets you know that you are buying a draft of a sequel that you won't enjoy unless you keep To Kill a Mockingbird in the back of your mind at all times while reading.

The Millions Top Ten: March 2016

We spend plenty of time here on The Millions telling all of you what we’ve been reading, but we are also quite interested in hearing about what you’ve been reading. By looking at our Amazon stats, we can see what books Millions readers have been buying, and we decided it would be fun to use those stats to find out what books have been most popular with our readers in recent months. Below you’ll find our Millions Top Ten list for March.

This Month

Last Month

Title

On List

1.

2.

Fortune Smiles

4 months

2.

3.

Slade House

6 months

3.

4.

The Big Green Tent

5 months

4.

5.

What Belongs to You

3 months

5.

6.

My Name is Lucy Barton

3 months

6.

10.

The Past

2 months

7.

9.

A Brief History of Seven Killings

4 months

8.

-

Girl Through Glass

1 month

9.

8.

City on Fire

6 months

10.

-

The Lost Time Accidents

1 month

Ascend, ascend Lauren Groff and Margaret Atwood! Set forth and lay claim to your spots within our Millions Hall of Fame. For one of these authors, it's their second time making the list. For the other, it's their debut. Can you guess which is which? The answer may surprise you.

And with the ascension of Fates and Futures and The Heart Goes Last, we welcome two newcomers to our monthly Top Ten: Girl Through Glass by Sari Wilson and The Lost Time Accidents by John Wray.

In his write-up for our Most Anticipated Book Preview three months ago, Matt Seidel described how Wilson's novel "alternates between late-1970s New York, where its heroine works her way into George Balanchine’s School of American Ballet, and the present day, where she is a dance professor having an affair with a student." It's a novel ripe with dramatic tension, and one more than a little fixated on body type, as Martha Anne Toll noted in her recent exploration of women -- lost, thin, and small -- in fiction.

Joining Wilson on the list this month is John Wray, whose newest novel, The Lost Time Accidents, covers a great many topics, such as physics, the Czech Republic, watch factories, Nazi war criminals, the Church of Scientology (but not really), and science fiction, among others. In her write-up for the Book Preview, Anne K. Yoder called it a "mash-up of sci-fi, time-travel, and family epic [that's] both madcap and ambitious." The novel was also covered by Michael Schaub in a recent edition of The Book Report -- come for the overview, but stay for Bong Crosby!

Stay tuned for next month's list, in which two more newcomers are poised to join our ranks.

This month's near misses included: The Queen of the Night, Mr. Splitfoot, The Turner House, Eternity Street: Violence and Justice in Frontier Los Angeles, and The Sellout. See Also: Last month's list.

The Tournament of Books

Welcome to a new episode of The Book Report presented by The Millions! This week, Janet and Mike got to serve as commentators for The Morning News Tournament of Books. They discuss the results, as well as some of the surprises along the way.

Discussed in this episode: The Sellout by Paul Beatty, The Tsar of Love and Techno by Anthony Marra, basketball, Fates and Furies and Arcadia by Lauren Groff, Bats of the Republic by Zachary Thomas Dodson, The Turner House by Angela Flournoy, A Little Life by Hanya Yanagihara, A Spool of Blue Thread by Anne Tyler, Jeff VanderMeer.

Not discussed in this episode: Mike's unfortunate prediction that A Gronking to Remember by Lacey Noonan would go all the way this year.

The Millions Top Ten: February 2016

We spend plenty of time here on The Millions telling all of you what we’ve been reading, but we are also quite interested in hearing about what you’ve been reading. By looking at our Amazon stats, we can see what books Millions readers have been buying, and we decided it would be fun to use those stats to find out what books have been most popular with our readers in recent months. Below you’ll find our Millions Top Ten list for February.

This Month

Last Month

Title

On List

1.

1.

Fates and Furies

6 months

2.

4.

Fortune Smiles

3 months

3.

3.

Slade House

5 months

4.

5.

The Big Green Tent

4 months

5.

8.

What Belongs to You

2 months

6.

9.

My Name is Lucy Barton

2 months

7.

6.

The Heart Goes Last

6 months

8.

7.

City on Fire

5 months

9.

10.

A Brief History of Seven Killings

3 months

10.

-

The Past

1 month

For the first time in five years, but also the third time in six, Jonathan Franzen sent one of his books to our site's Hall of Fame. And with the ascension of Purity, that makes Franzen three-for-three on his most recent novels reaching such hallowed ground. (Sorry, Kraus Project, but it looks like the streak is limited to fiction; and sorry as well, Strong Motion, but it looks like you arrived before the Franz-y* picked up full force; you'll have to content yourself with Brain Ted Jones's Millions essay instead of a HoF berth.)

Filling Purity's spot this month is The Past by Tessa Hadley, which was featured in both our Second-Half 2015 and also our Great 2016 Book Previews. The novel concerns siblings who reunite to sell their grandparents’ old house, but it really shouldn't be summed up by its plot. The author would protest. After all, in an interview for our site last year, Hadley remarked upon the dangers that come from focusing too narrowly on plot and sequential order, and how she controls that impulse when she writes:

Things in life don’t, on the whole, add up or get resolved in that deliciously satisfactory, finalizing way that novels are so good at. Nineteenth-century novelists resolved their plotty novels so magnificently because they shared convictions about meaning and fulfillment that we surely mislaid somewhere in the 20th century. But I do believe that “leaping over the gaps” doesn’t mean you can’t hold a story together. Rather, we’ve grown suspicious of stories that resolve too satisfactorily. The danger is that if you fill in all the gaps you lose the essence of the story, you write something stodgy and merely consecutive, instead of keeping your hand on the live wire of the life, which jumps from place to place.

Elsewhere on this month's list we see Marlon James's A Brief History... move up on spot, which is good because that means you're listening to my repeated pleas for you to buy that book. It also appears that next month our list will welcome two new additions, as both Fates and Furies and The Heart Goes Last seem destined for the Hall of Fame.

*No, I don't want to apologize for that. It was good.

This month's near misses included: The Queen of the Night, The Lost Time Accidents, Eternity Street: Violence and Justice in Frontier Los Angeles, Girl Through Glass, and The Turner House. See Also: Last month's list.

The Millions Top Ten: January 2016

We spend plenty of time here on The Millions telling all of you what we’ve been reading, but we are also quite interested in hearing about what you’ve been reading. By looking at our Amazon stats, we can see what books Millions readers have been buying, and we decided it would be fun to use those stats to find out what books have been most popular with our readers in recent months. Below you’ll find our Millions Top Ten list for January.

This Month

Last Month

Title

On List

1.

3.

Fates and Furies

5 months

2.

4.

Purity

6 months

3.

5.

Slade House

4 months

4.

7.

Fortune Smiles

2 months

5.

8.

The Big Green Tent

3 months

6.

9.

The Heart Goes Last

5 months

7.

10.

City on Fire

4 months

8.

-

What Belongs to You

1 month

9.

-

My Name is Lucy Barton

1 month

10.

-

A Brief History of Seven Killings

2 months

It's with a certain degree of triumph that I welcome Marlon James to the first Millions Top Ten of 2016. While this isn't the first time his superb novel A Brief History of Seven Killings has appeared on our list overall — that first occurred in October of last year — it nevertheless feels a bit like a personal victory for me, the humble author of this series, who has since that time urged each and every one of you to go out and purchase a copy (or three!) immediately. Well, it finally seems that the work has paid off. (Happy New Year to me!) Now let's work on keeping it here, eh?

This month we graduated three Top Ten fixtures to our Hall of Fame: Ta-Nehisi Coates's Between the World and Me, Hanya Yanagihara's A Little Life, and Harper Lee's Go Set a Watchman. The first two were fixtures atop our list for the past six months, while Lee's Mockingbird sequel-prequel got off to a hot start before ultimately settling in the middle of our ten-book pack.

Their success means Lauren Groff's Fates and Furies is the new top book in town. It's a novel that Margaret Eby described in her Year in Reading entry as the kind "I would start reading on a Saturday morning and soon find myself cancelling weekend plans to finish by Sunday night." To get acquainted with it, I recommend first checking out our exclusive first look at its opening lines, and then settling in for our interview with its author. If somehow you're still not convinced that this is a book you absolutely need to read in full, immediately, then allow our own Edan Lepucki's praise to coax you over the threshold:

I have read all of Groff’s novels, and each one is better than the last, which gives me vicarious hope for my own puny literary pursuits. I get the sense that Groff is always looking for new ways to tell stories, to show time passing, to express human longing, shame, desire, need, all without succumbing to the same-old conventions of scenic conflict and cause-and-effect. Plus, her prose is so shining and unexpected she could describe getting her license renewed at the DMV and I’d find it compelling.

Also this month in addition to A Brief History... we welcome two newcomers to our list: Garth Greenwell's What Belongs to You and Elizabeth Strout's My Name is Lucy Barton. Both novels have received heaps of praise — both appeared on our Most Anticipated preview — but Greenwell's in particular has been drawing some seriously effusive reviews. On our site, Jameson Fitzpatrick wrote that What Belongs to You "offers us the most exacting and visionary reading in contemporary literature of what it means to be gay in America today."

This month's near misses included: Eternity Street: Violence and Justice in Frontier Los Angeles, The Turner House, The 3 A.M. Epiphany, Undermajordomo Minor, and A Strangeness in My Mind. See Also: Last month's list.

The Millions Top Ten: December 2015

We spend plenty of time here on The Millions telling all of you what we’ve been reading, but we are also quite interested in hearing about what you’ve been reading. By looking at our Amazon stats, we can see what books Millions readers have been buying, and we decided it would be fun to use those stats to find out what books have been most popular with our readers in recent months. Below you’ll find our Millions Top Ten list for December.

This Month

Last Month

Title

On List

1.

1.

Between the World and Me

6 months

2.

2.

A Little Life

6 months

3.

6.

Fates and Furies

4 months

4.

3.

Purity

5 months

5.

4.

Slade House

3 months

6.

5.

Go Set a Watchman

6 months

7.

-

Fortune Smiles

1 month

8.

10.

The Big Green Tent

2 months

9.

9.

The Heart Goes Last

4 months

10.

8.

City on Fire

3 months

After being crowned the 2015 National Book Award winner, Fortune Smiles by Adam Johnson has received an even greater honor: entry onto The Millions's December 2015 Top Ten list! The collection was described in our second-half Book Preview* as being “six stories, about everything from a former Stasi prison guard in East Germany to a computer programmer ‘finding solace in a digital simulacrum of the president of the United States,’” and it was said to “echo” the author's “early work while also building upon the ambition of his prize-winning tome.”

Elsewhere on the list, small shakeups abound. Fates and Furies and The Big Green Tent rose three and two spots, respectively, while Garth Risk Hallberg's City on Fire moved from the eighth spot to the tenth. Beyond that? There isn't too much to report.

Next month, however, three fixtures on our list— Between the World and Me, A Little Life, and Go Set a Watchman — will likely head to our Hall of Fame, and their ascendance should free up space for fresh blood. They'll join Book of Numbers by Joshua Cohen, which joins the Hall this month. If past is prologue, most of those newcomers will have been culled from our Year in Reading series. If so, do you have any guesses on which ones will become fan favorites? Will it be another installment of Elena Ferrante's Neapolitan Quartet? (The first one's already in our Hall...) Will it be Maggie Nelson's The Argonauts? And whatever it may be, will it have a Florida connection?**

Stay tuned to find out.

* Speaking of Previews, have you checked out the first installment of our Great 2016 Book Preview, which posted this week?

** Probably. Everything does.