This year I wanted to read the last six Philip Roth novels I hadn’t read yet. While I wouldn’t call it a mistake, I will say it was like eating a six-pack of paper towels, and I say this as a longtime Roth head (Rothster? Rothario?), though he doesn’t really make admiration easy, the more you learn about him. You just have to accept that a guy who once faxed his ex-wife a bill for 62 billion dollars and was once described to me by one of his colleagues as “a Shit of Hell” can also write good books.

Sadly, this was not a year for the good ones, and it turns out his minor works don’t come up often for a reason. The first gaps to fill were the two novels after his debut collection Goodbye, Columbus. People tend to regard first novels as mission statements, but neither one bears much of Roth’s trademark topoi (penile slapstick, high-octane rants, New Jersey, Judaism, Philip Roth). Letting Go (1962) has a germ of the resentfully dutiful male leads and unstable love interests we see all throughout Roth, but it’s mostly a tame and VERY LONG exercise in conventional midcentury themes of conformity, adultery, and divorce. When She Was Good (1967), best known these days probably as a namecheck in an episode of Girls (“American Bitch,” the novel’s aprocryphal working title*). It is interesting mainly in that it’s Roth’s only book-length attempt at a female protagonist, and you can feel his joints bending the wrong way; his depiction of the rage-filled Lucy Nelson often comes off as rage toward Lucy Nelson.

Sadly, this was not a year for the good ones, and it turns out his minor works don’t come up often for a reason. The first gaps to fill were the two novels after his debut collection Goodbye, Columbus. People tend to regard first novels as mission statements, but neither one bears much of Roth’s trademark topoi (penile slapstick, high-octane rants, New Jersey, Judaism, Philip Roth). Letting Go (1962) has a germ of the resentfully dutiful male leads and unstable love interests we see all throughout Roth, but it’s mostly a tame and VERY LONG exercise in conventional midcentury themes of conformity, adultery, and divorce. When She Was Good (1967), best known these days probably as a namecheck in an episode of Girls (“American Bitch,” the novel’s aprocryphal working title*). It is interesting mainly in that it’s Roth’s only book-length attempt at a female protagonist, and you can feel his joints bending the wrong way; his depiction of the rage-filled Lucy Nelson often comes off as rage toward Lucy Nelson.

Next to choke down was the three-book bolus following Portnoy’s Complaint, the beginning of a decade-long refractory period, in a register of zany absurdism. Our Gang (1971) is a politically well-intentioned satire of the hypocrisies of the Nixon administration, whose protagonist is named Trick E. Dixon. The novella The Breast (1972), about what if a guy turned into a tit, isn’t much better, but is shorter; and The Great American Novel (1973) is the hands-down career nadir, 382 pages of stupendously unfunny baseball gags (protagonist name: Word Smith). Roth once said that out of all his books, that one was the most fun to write—well I’m glad someone was having a good time.

Next to choke down was the three-book bolus following Portnoy’s Complaint, the beginning of a decade-long refractory period, in a register of zany absurdism. Our Gang (1971) is a politically well-intentioned satire of the hypocrisies of the Nixon administration, whose protagonist is named Trick E. Dixon. The novella The Breast (1972), about what if a guy turned into a tit, isn’t much better, but is shorter; and The Great American Novel (1973) is the hands-down career nadir, 382 pages of stupendously unfunny baseball gags (protagonist name: Word Smith). Roth once said that out of all his books, that one was the most fun to write—well I’m glad someone was having a good time.

My last two to finish it off, near Roth’s terminus, neatly represent Late Roth’s two main concerns. The Humbling (2009), like his earlier Exit Ghost and Everyman, is a minor-key musing on mortality and senescence, but feels like a rehash of the superior Sabbath’s Theater, all the way down to the “stage performer reclaims his lost joie de vivre via unbecoming sexual affair” setup. Late Roth is also interested in guys who get utterly hosed by history, and that’s what we get in Indignation (2008), narrated posthumously by a prideful, serious-minded kid whose choices eventually get him turned into raw hamburger in Korea. Of his last five books, this is probably my favorite, with some of the formal jaunts and sex farce that make Roth fun to read, but I can’t really recommend anything after 9/11.

My last two to finish it off, near Roth’s terminus, neatly represent Late Roth’s two main concerns. The Humbling (2009), like his earlier Exit Ghost and Everyman, is a minor-key musing on mortality and senescence, but feels like a rehash of the superior Sabbath’s Theater, all the way down to the “stage performer reclaims his lost joie de vivre via unbecoming sexual affair” setup. Late Roth is also interested in guys who get utterly hosed by history, and that’s what we get in Indignation (2008), narrated posthumously by a prideful, serious-minded kid whose choices eventually get him turned into raw hamburger in Korea. Of his last five books, this is probably my favorite, with some of the formal jaunts and sex farce that make Roth fun to read, but I can’t really recommend anything after 9/11.

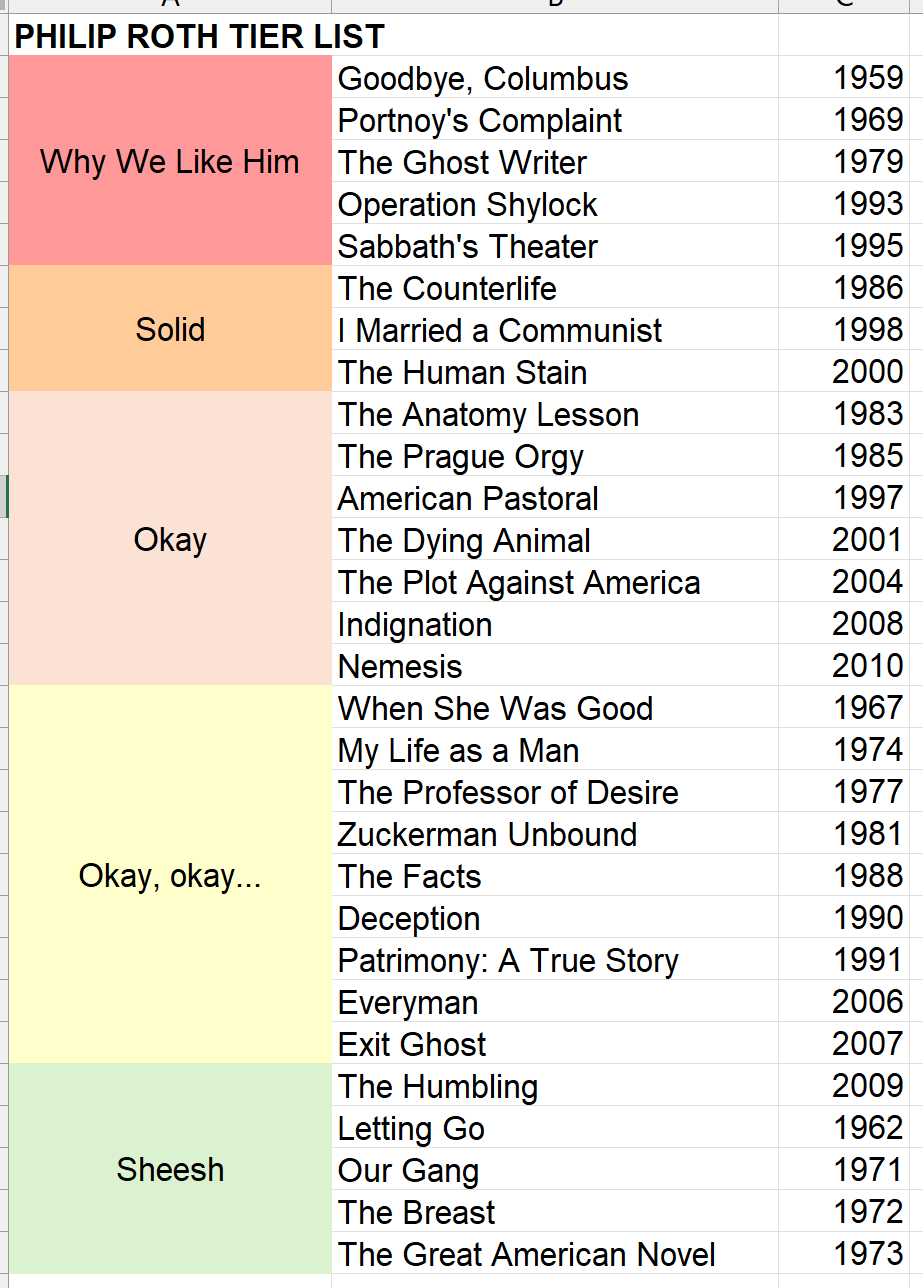

Of course misfires are necessary and inevitable, and I’d like to think that when writers flop, even several times, it doesn’t tarnish their best books, though it’s understandable if the reader becomes a bit less forgiving overall. So while it’s fine that these books exist, it also reminds you how there exists a kind of tenure system for novelists, where by dint of publishing regularly and selling reliably—say a book every 2-4 years—one can get away with books that would never, ever see publication from an unknown debut writer. Still, I think the good books are what matters, and we can just eat around the rest; by this accounting Roth figures as equivalent in merit to Charles Portis, who also wrote five great and distinctive novels. And speaking of accounting, here is my Excel tier list of all of his books, in my hobbyist opinion:

This year I also read all of another novelist’s books, but it only took me three days—the autobiographical graphic novels of Kabi Nagata, a reclusive artist who writes with incredible honesty about her grapples with mental health, social anxiety, sexuality, loneliness, underemployment, disordered eating, alcoholism and subsequent pancreatitis, sexual assault, and also the notoriety of writing the series itself. If you’ve ever seen Baby Reindeer, you’ll recall the feeling of mounting disbelief at each new layer of tribulation disclosed, and a similar unfolding is at work here. One difference, however, is that Nagata is not writing with any hindsight; she’s like one of those TV reporters they send into the middle of a hurricane. Nonetheless she maintains throughout a basically cheerful presentation of her struggles, which can be read in many ways. Is it heroic cope? A consoling blitheness? A symptom of delusion? An ironic underscoring of her misery? A bit of concern bait—the equivalent of saying I’m fine, don’t worry about me? The way it careens through these different reads throws a fascinating ambiguity over how we’re meant to receive the story.

This year I also read all of another novelist’s books, but it only took me three days—the autobiographical graphic novels of Kabi Nagata, a reclusive artist who writes with incredible honesty about her grapples with mental health, social anxiety, sexuality, loneliness, underemployment, disordered eating, alcoholism and subsequent pancreatitis, sexual assault, and also the notoriety of writing the series itself. If you’ve ever seen Baby Reindeer, you’ll recall the feeling of mounting disbelief at each new layer of tribulation disclosed, and a similar unfolding is at work here. One difference, however, is that Nagata is not writing with any hindsight; she’s like one of those TV reporters they send into the middle of a hurricane. Nonetheless she maintains throughout a basically cheerful presentation of her struggles, which can be read in many ways. Is it heroic cope? A consoling blitheness? A symptom of delusion? An ironic underscoring of her misery? A bit of concern bait—the equivalent of saying I’m fine, don’t worry about me? The way it careens through these different reads throws a fascinating ambiguity over how we’re meant to receive the story.

Final shoutouts go to Barbara Browning’s The Gift, Nafissa Thompson-Spires’s Heads of the Colored People, Charlotte Shane’s An Honest Woman, Paul Murray’s The Bee Sting, Rachel Aviv’s Strangers to Ourselves, Elaine Kraf’s The Princess of 72nd Street, Joseph Earl Thomas’s God Bless You, Otis Spunkmeyer, and a giant foam finger for Susie Boyt’s Loved and Missed, which I’ll write about elsewhere.

Final shoutouts go to Barbara Browning’s The Gift, Nafissa Thompson-Spires’s Heads of the Colored People, Charlotte Shane’s An Honest Woman, Paul Murray’s The Bee Sting, Rachel Aviv’s Strangers to Ourselves, Elaine Kraf’s The Princess of 72nd Street, Joseph Earl Thomas’s God Bless You, Otis Spunkmeyer, and a giant foam finger for Susie Boyt’s Loved and Missed, which I’ll write about elsewhere.

More from A Year in Reading 2024

*I actually got to ask Lena Dunham about this, and she said she heard it from her mom’s friend.