●

●

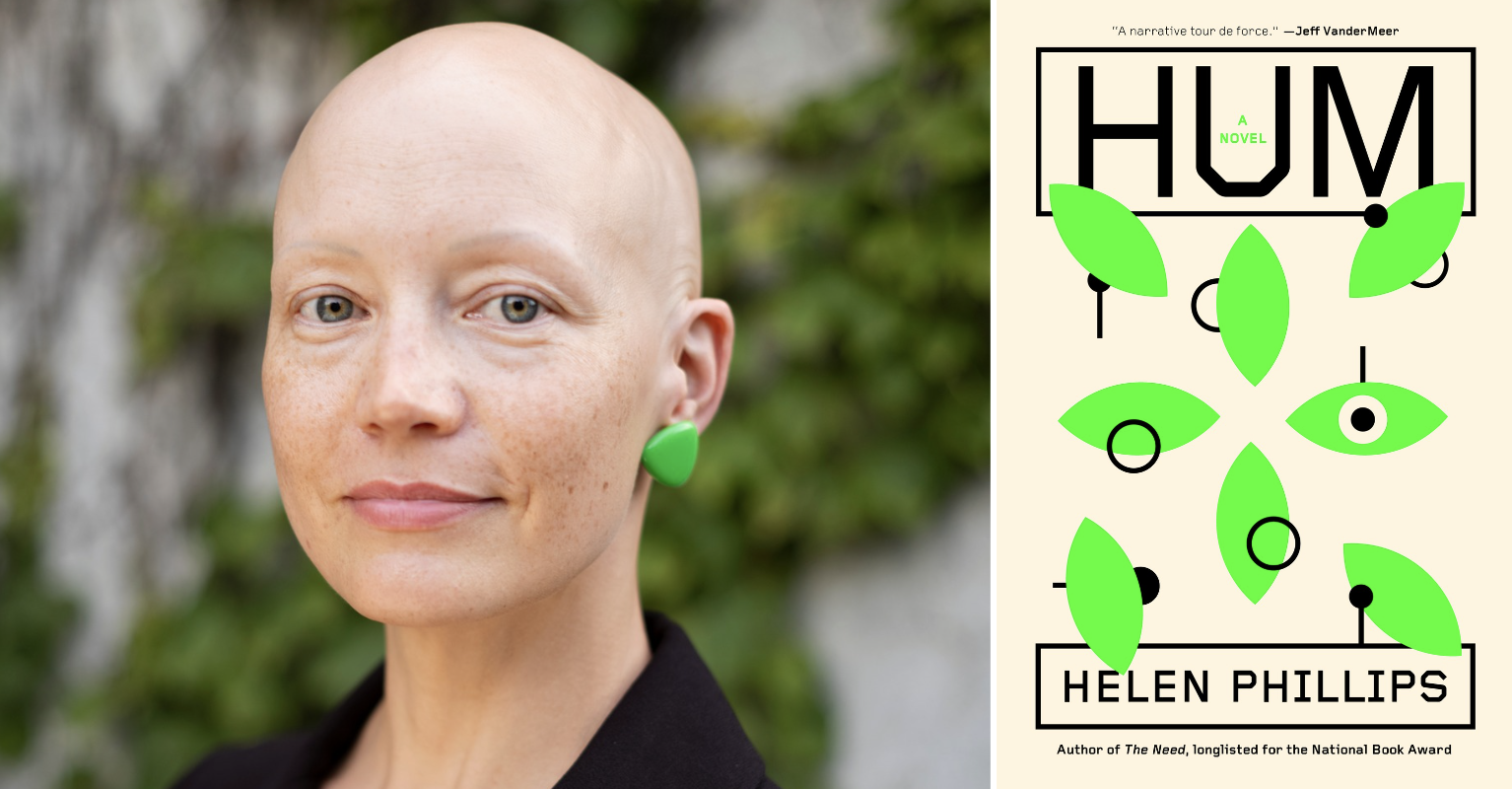

Helen Phillips Isn’t Afraid of the Algorithm

Some of the intrigue and fascination with artificial intelligence is very much in the realm of fantasy, because it seems that, so far, algorithms tend to accelerate bias and emphasize the worst aspects of human behavior.

●

●

●

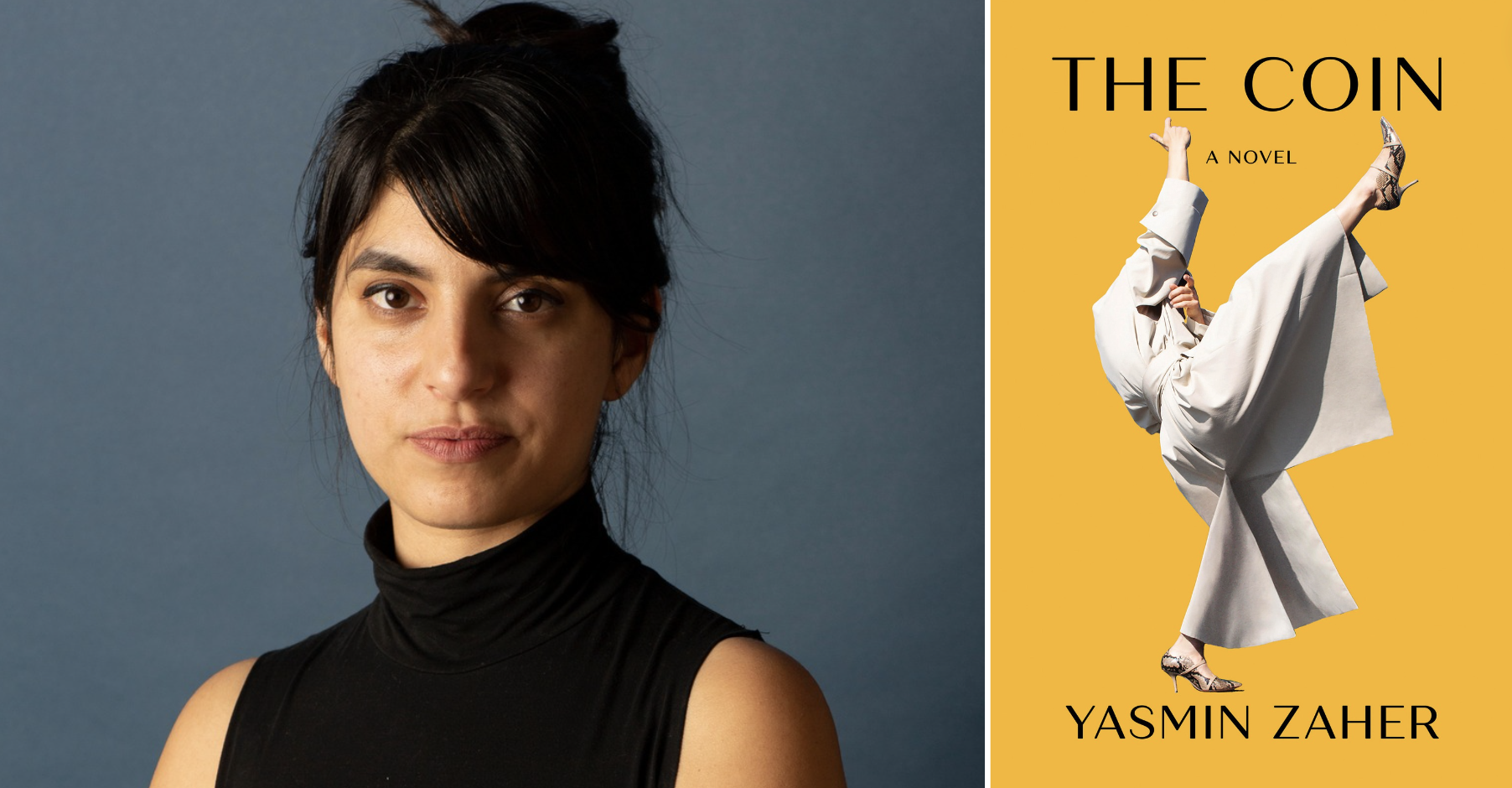

How Yasmin Zaher Wrote the Year’s Best New York City Novel

"This is going to sound absurd, but in a novel, you can say the truth, and in journalism, you cannot."

●

●

●

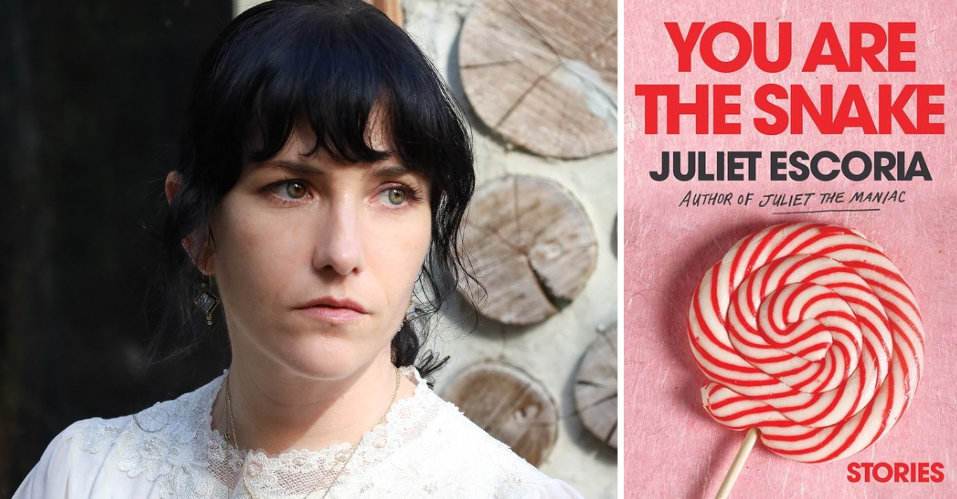

Juliet Escoria Wants to Bring Back Fistfights

In internet fights, people use this faux veneer of politeness, where they will veil something nasty with corporate HR language, and I find it morally repugnant.

●

●

●

Glynnis MacNicol on Marriage, Pleasure, and Orgasmic Narratives

"There’s no sense in a capitalist society that enjoying your life should be the basis for anything."

●

●

●

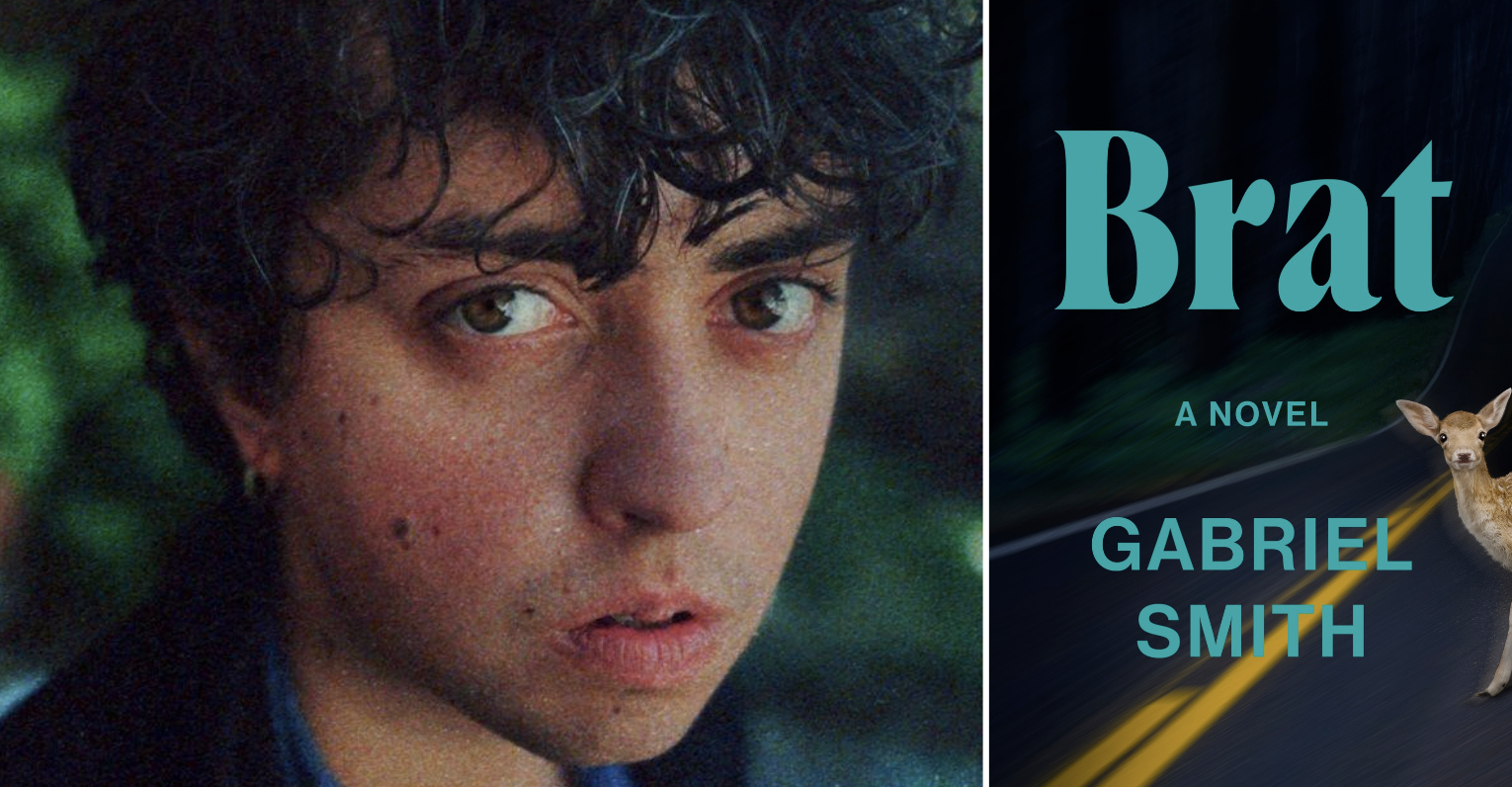

Gabriel Smith Writes Like He Has Nothing Left to Lose

"I think that almost all of the work under the 'autofiction' banner is politically corrupt."

●

●

●

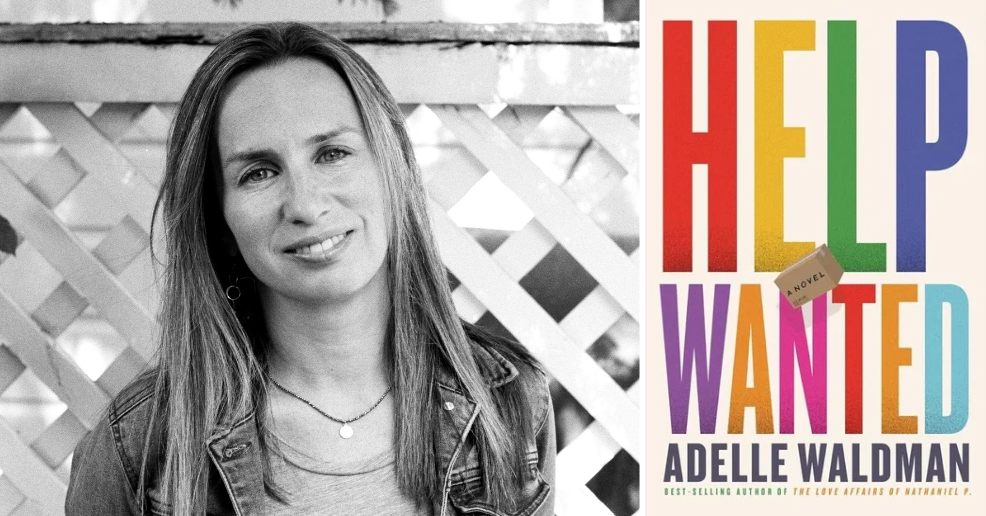

Adelle Waldman on Her

‘Nickel and Dimed’–Inspired Novel

"I think too many people—and I include myself in this—find ways of staying insulated from that reality."

●

●

●

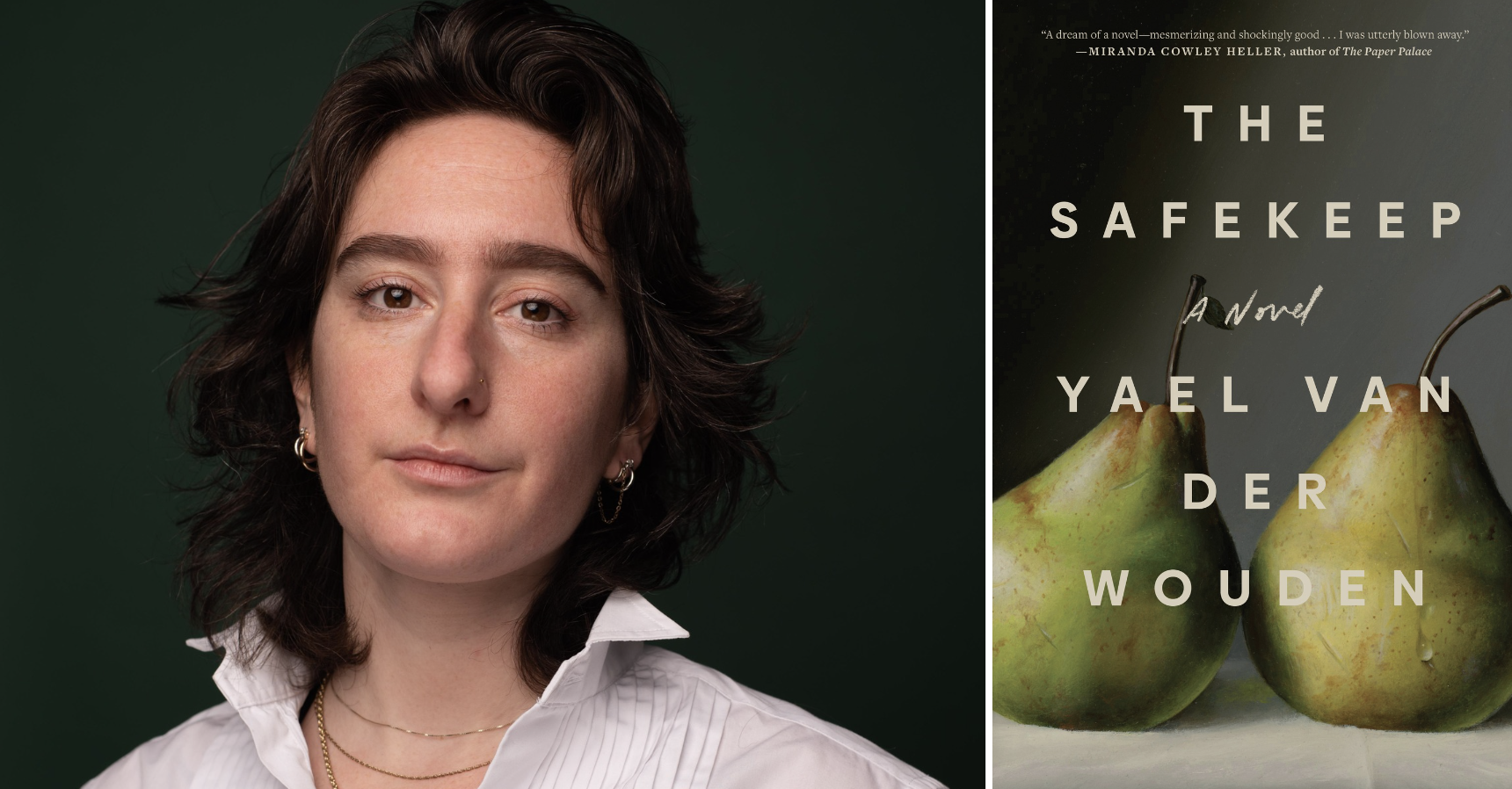

Yael van der Wouden Wants to Touch Everything

"The moment the sex turns gratuitous you lose the tension, and therein the emotional investment of your readers."

●

●

●

Lilly Dancyger Is Rethinking the Ethics of Memoir

"I do think that we, as writers, owe things to the people in our lives that we care about."

●

●

●

Why Write Memoir? Two Debut Authors Weigh In

"It was hard on many levels, and I had to keep going back to why I was writing in the first place."

●

●

●

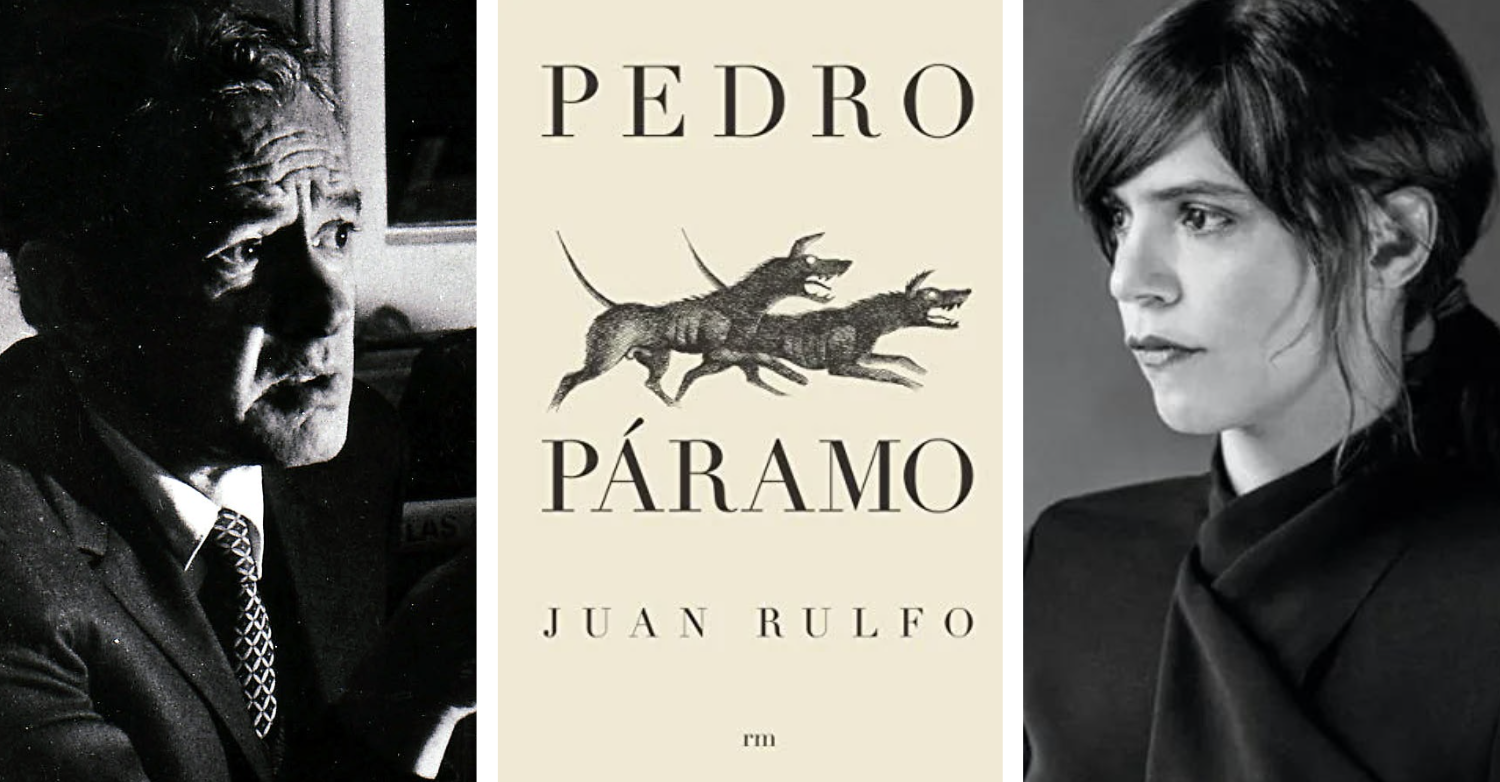

“You Can Almost Hear the Ghosts”:

Valeria Luiselli on Juan Rulfo

"Rulfo travels in time and space with an absolute freedom without us getting lost."

●

●

●