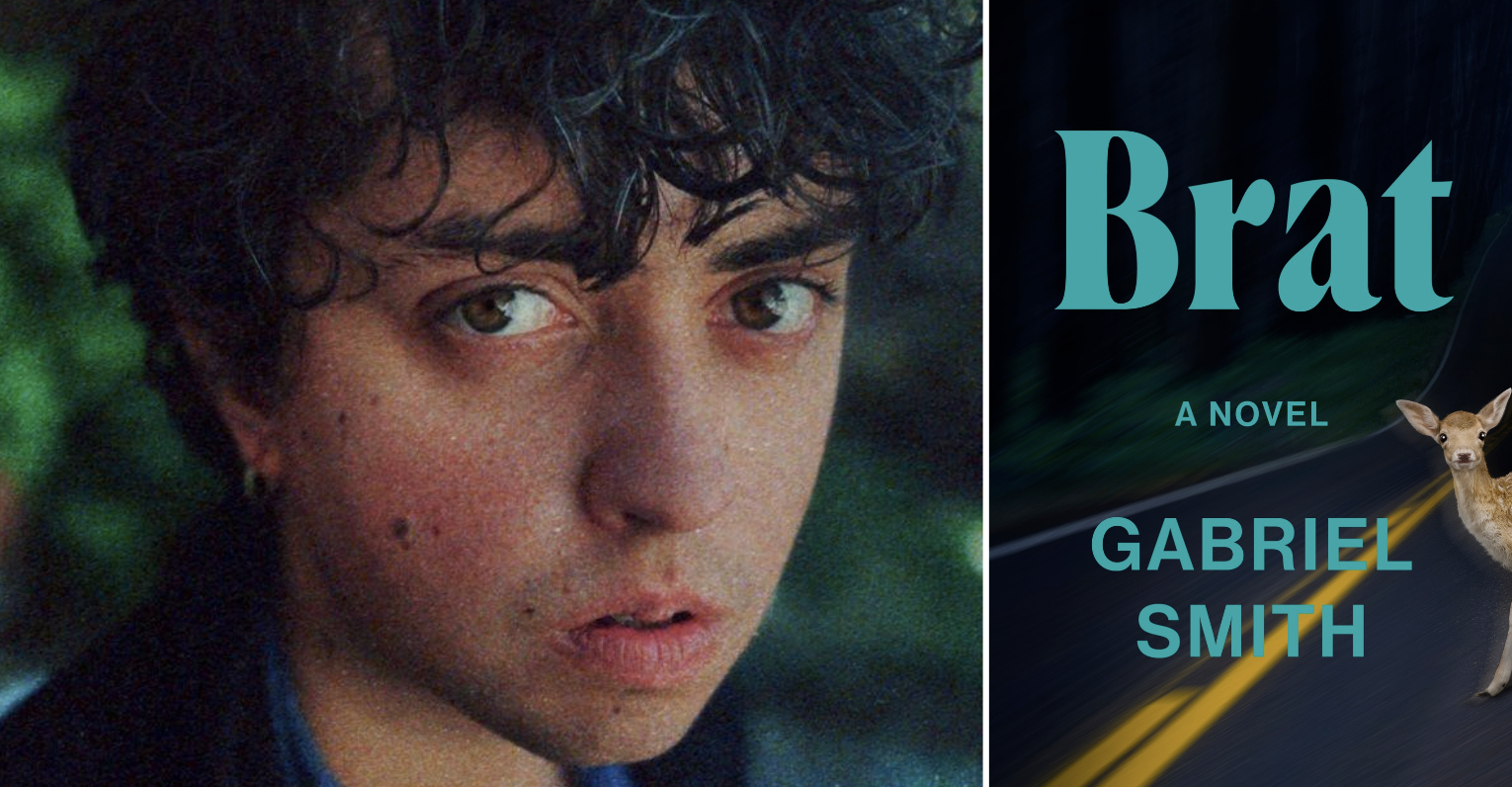

The most exciting thing to encounter in the world of publishing is a writer who doesn’t sound like anyone else. I first read Gabriel Smith at the Drift, where our then fiction editor spied his story, “The Complete,” in the slush, so it’s been a thrill to help bring out his debut novel, Brat, in my other role as an editor at Penguin Press. Brat is sharp, wickedly funny, moving, unusual, spooky, haunted, textually layered—the adjectives sort of flow endlessly. It’s a book you’ll keep turning over in your mind long after you’ve read it, which is why I relished the opportunity to chat with Gabe about the project of Brat and the process of writing fiction. I sent over some questions in the format every writer and editor loves most—Google Docs—and I hope you’ll enjoy his responses (and Brat itself) as much as I did.

Kiara Barrow: The U.K. edition of Brat is being published with the subtitle “A Ghost Story.” For the U.S., we went with the slightly more classic “A Novel,” in order to more straightforwardly telegraph its scope, ambition, and basic genre. Perhaps we were too quick to assume American readers have a lower tolerance for a tongue-in-cheek subtitle. Nevertheless, I’d love to hear how you think about genre and this book, which, yes, features ghosts, and to my mind draws on other literary traditions including horror (body and otherwise), the gothic, and the perhaps slightly more contemporary autofictional mode. How important are generic conventions to you? Is thinking about them productive or constraining?

Gabriel Smith: Actually I think Americans have a higher tolerance for novels! I didn’t choose either subtitle, to be quite clear. And I don’t know how tongue-in-cheek the U.K. one is. I think they’re trying to sell more copies to horror fans. You Americans sometimes think we’re being smarter or more ironic than we actually are.

One thing I love about horror, the gothic, whatever, is how strong the images are. You can watch the worst horror movie and it’ll have more interesting images than 99% of “literary fiction.” I doubt I’ll write another horror-adjacent novel, but I enjoyed the constraints of working partially within a genre. It’s good to have something to break.

KB: I am sorry—both to you and our readers—to harp on this one, but given the central role autofiction has played in the literary conversation over the past few years, it’s a difficult topic to avoid entirely when confronted with an author named Gabriel and a main character also named Gabriel. Should we talk about it? Is autofiction over? Is it still a valuable lens? Do you cosign everything Gabriel says in the novel?

GS: Autofiction is dead and Brat has killed it. No, only joking. In pop culture—especially debut novels, singles, films—“authenticity” is really important to audiences at the moment. The parasocial element. Like the biggest thing in the Kendrick/Drake spat that’s happening right now is who has the best gossip. So I had to roll with the dominant mode to some extent, and I think it’s a mode that’s produced some really wonderful novels. We should talk about it, because the form does have value as a mirror. I just prefer my art prismatic.

But I also think that almost all of the work under the “autofiction” banner is politically corrupt. I think it’s narcissistic in a bad way, extremely boring, and a dead end stylistically. It’s strange that people talk like it’s a new form, which it obviously isn’t. So there’s something else going on.

I’m of the opinion that its dominance reflects an inability or unwillingness to imagine alternatives to the present. But guess what—that is the literal job of the novelist. So the last decade or two, I think a lot of the work people have done in our tiny section of culture has either been from a place of incompetence, or just straight laziness. I think audiences have noticed that. Part of what the structure of Brat is about is exploding the mode. The protagonist of it has this very autofiction voice. And then the fictional just assaults him.

Obviously I don’t cosign everything fictional me says. The slurs Gabriel says in the novel, for example—people on Goodreads keep docking me stars for what the character says, and it’s like: If it’s not a creative choice to build character, do you think I am just addicted to writing slurs? Like I can’t stop myself?

KB: I know, from hearing you talk about it, that Brat—and your writing in general—bears the mark of a lot of non-literary influences. But I don’t think it’ll surprise your readers that films and music are important creative touchstones for you. Could you give us some insight into how that works, and how you see writing in dialogue with other art forms?

GS: Yeah, mainly it’s that I want my shit to look good and sound good. But I do think that over the last couple of decades there has been a lot of innovation in other art forms, music especially, and that fiction is quite a way behind. Novels don’t even really have sampling yet, something that’s been around explicitly in music since at least Charlie Parker. It’s fucked.

So it’s very important for me to be working in dialogue with these forms. For example, Brat is very sample-driven, and I was thinking very specifically about how samples are used in U.K. post-rave music and in vaporwave, the way those forms are haunted by warped, recurring samples.

There’s a deep luddite sentiment in literature generally. It’s embarrassing. Look at the response to AI language generation. It’s so precious, and self-centered, and I find it very hard to believe that most novelists care at all about their audience, let alone pushing the form forward. What would the Modernists have done with the tools and techniques we have now? What would Joyce be doing?

KB: Publishing timelines mean writers will often have finished a project years before it’s released, and are then asked to return and explain and re-inhabit their earlier selves and processes when doing press and promotion. How does it feel to be talking about Brat now? I think our readers would also be interested in the winding road the novel has taken to publication, and how that felt for you. Does any of this inform what you’re working on next, or how you’re doing so?

GS: Yeah, I mean, I wrote this thing in 2019, when I was 24. Its first editor was Giancarlo DiTrapano, of New York Tyrant, and he was going to put it out. But he passed in 2021, about six weeks before he was going to announce it.

I loved him very much. Gian was my hero when I was a teenager, getting into books, and he was more of a friend than an editor. So losing him was like losing three people. I think all of his writers felt that way. Everyone grieves differently, and I’m not good with it, which is probably evident in Brat.

So when people came asking about Brat, especially after you published “The Complete” in The Drift and it did mad numbers, I really didn’t feel like it was mine to sell. I sent some very aggressive responses to emails which I should probably apologize to people for at some point. I ended up just shelving Brat for ages and working on new stuff.

But also I’m not sorry at all to those people, the people who came disrespectfully or insensitively. Because when someone passes, and you have something of theirs, their work, you become a custodian of their legacy whether you like it or not. That responsibility is a part of being alive, of surviving.

I’m very lucky to have found two people in you and Chris at Scribner UK who get it, and who are both incredibly talented editors, and dignified, and who I can trust not just with Brat but with future stuff. There isn’t another way I could have published this book, I don’t think. You probably don’t know how grateful I am.

In terms of what I’ve worked on since, and will work on in the future: the only literary aspiration I ever had was to write a book for Gian. He really was my hero. So when he was taken from us it left me with nobody I cared about pleasing or pandering to. And for that aspiration to be within reach, and then gone: for the work, it’s freeing.

Gian once said to me, and I believe it’s a Gordon Lish line: The thing taken from you is your gift. I don’t think most authors get to see quite how transient the material/ego rewards are at the beginning of their career, before they’ve even had a book out. Or for it to be shown quite so starkly.

It’s confusing because I miss him so much. But also I can write like I don’t have anything left to lose, or to gain, because I don’t. Maybe this all sounds self-important or overly sincere. I don’t really care.