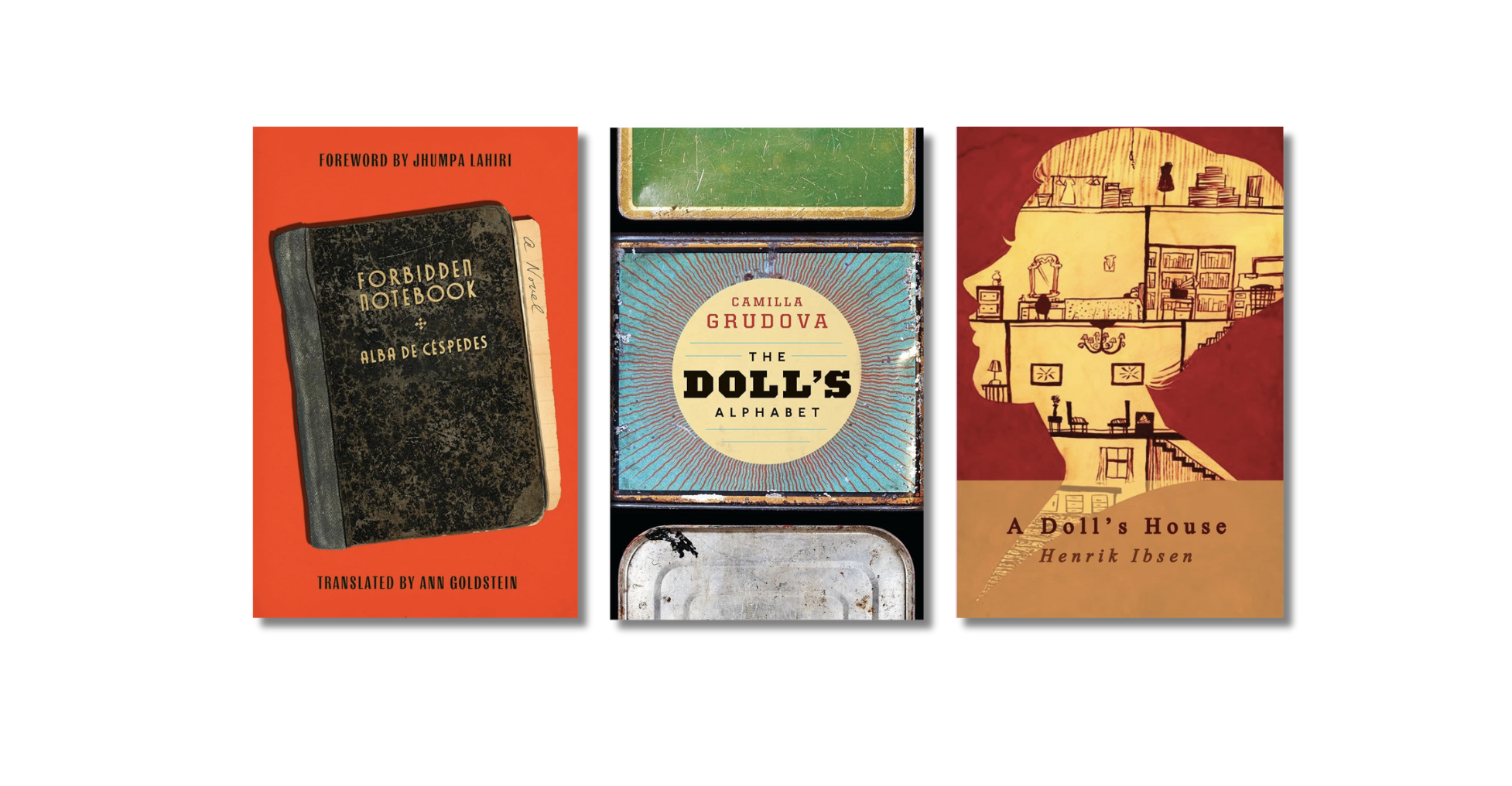

Most of my reading this year went towards studying fairy tales. I know, I know—the fairy tale has fallen out of favor. There’s a naive domesticity associated with its tales of marriage and castles and princes. Still, I found that learning their structures and tropes, and surrendering to their illogical sequence of events, left an imprint on my own writing. I began with the Grimm and Perrault fairy tale collections before turning to writers that draw upon them for inspiration, such as the feminist retellings of Angela Carter’s The Bloody Chamber and Camilla Grudova’s The Doll’s Alphabet. I began to see how the fairy tale’s refusal to explain the logic of its world invites a variety of interpretations, and moved into Bettelheim‘s Freudian analysis in The Uses of Enchantment and Christina Campo’s mystical investment in The Unforgivable. Trapped by the spell of the fairy tale, I read further and ended up in the realm of romance for the first time in my life. I read Pamela Regis’s A Natural History of the Romance Novel to get my bearings and then—I can’t believe I’m admitting this—Sarah J. Maas’s A Court of Thorns and Roses, which is ostensibly based on Beauty and the Beast. Each of these retellings and interpretations cannot possibly have been the intentions of the original tellers, and yet each of them make sense. I’m still reading through the fairy tale: after the myth, it is literature’s second great changeling.

Most of my reading this year went towards studying fairy tales. I know, I know—the fairy tale has fallen out of favor. There’s a naive domesticity associated with its tales of marriage and castles and princes. Still, I found that learning their structures and tropes, and surrendering to their illogical sequence of events, left an imprint on my own writing. I began with the Grimm and Perrault fairy tale collections before turning to writers that draw upon them for inspiration, such as the feminist retellings of Angela Carter’s The Bloody Chamber and Camilla Grudova’s The Doll’s Alphabet. I began to see how the fairy tale’s refusal to explain the logic of its world invites a variety of interpretations, and moved into Bettelheim‘s Freudian analysis in The Uses of Enchantment and Christina Campo’s mystical investment in The Unforgivable. Trapped by the spell of the fairy tale, I read further and ended up in the realm of romance for the first time in my life. I read Pamela Regis’s A Natural History of the Romance Novel to get my bearings and then—I can’t believe I’m admitting this—Sarah J. Maas’s A Court of Thorns and Roses, which is ostensibly based on Beauty and the Beast. Each of these retellings and interpretations cannot possibly have been the intentions of the original tellers, and yet each of them make sense. I’m still reading through the fairy tale: after the myth, it is literature’s second great changeling.

It was Lydia Davis who, in Essays One, said to read a few classics every year, and I’ve followed her advice ever since. I finished, reluctantly, Henry James’s Portrait of a Lady—only so I can say with conviction that everyone who told me to read his overwrought and pompous prose is a fed (maybe one day I’ll get it). On the other hand, I picked up Edith Wharton’s The Custom of the Country from a bookseller outside Trader Joe’s, and loved the satire of a woman scheming to marry rich so much that I read Age of Innocence and House of Mirth, both much less funny if still lucid social critiques, and the first books to get me interested in New York at the turn of the century. Otherwise, two lesser-known classics I read and loved: Katherine Cecil Thurston’s Max, a 1910 novel about a princess fleeing an arranged marriage and hiding as a man in Paris. It transparently works through issues the author had with her confined role as a woman, with the princess even defending herself by saying that she “made [herself] a man, not for a whim, but as a symbol.” Similarly, I loved Henrik Ibsen’s A Doll’s House, a play from 1879 in which a disillusioned housewife makes the quite radical decision to leave her husband and kids. This predates, by almost a hundred years, a story that became ever-more common in the twentieth century (I’m thinking especially of Annie Ernaux’s A Frozen Woman).

It was Lydia Davis who, in Essays One, said to read a few classics every year, and I’ve followed her advice ever since. I finished, reluctantly, Henry James’s Portrait of a Lady—only so I can say with conviction that everyone who told me to read his overwrought and pompous prose is a fed (maybe one day I’ll get it). On the other hand, I picked up Edith Wharton’s The Custom of the Country from a bookseller outside Trader Joe’s, and loved the satire of a woman scheming to marry rich so much that I read Age of Innocence and House of Mirth, both much less funny if still lucid social critiques, and the first books to get me interested in New York at the turn of the century. Otherwise, two lesser-known classics I read and loved: Katherine Cecil Thurston’s Max, a 1910 novel about a princess fleeing an arranged marriage and hiding as a man in Paris. It transparently works through issues the author had with her confined role as a woman, with the princess even defending herself by saying that she “made [herself] a man, not for a whim, but as a symbol.” Similarly, I loved Henrik Ibsen’s A Doll’s House, a play from 1879 in which a disillusioned housewife makes the quite radical decision to leave her husband and kids. This predates, by almost a hundred years, a story that became ever-more common in the twentieth century (I’m thinking especially of Annie Ernaux’s A Frozen Woman).

I make a point to do a chunk of my reading each year in translation. I read Alba de Céspedes’s The Forbidden Notebook, (translated by Ann Goldstein) which turns the feminist call to “write yourself back into your body” on its head by featuring a mother who, after beginning to write in a diary, goes insane from the self-reflection it requires of her. I got an advanced copy of Vigdis Hjorth’s If Only (translated by Charlotte Barslund), which was unfortunately the same book as Ernaux’s Getting Lost, and the two are perhaps my least favorite of both of their oeuvres. Finally, I did a writing residency in the fall and brought Elena Ferrante’s Frantumaglia (also translated by Goldstein) with me. It was the last of her books I’ve yet to read, perhaps because, if I really love an author, I never like to finish everything they’ve written (this started at an early age—my sister makes fun of me for skipping the fifth season of Buffy so I’d always “have something to look forward to”). But as I set out on what I’m only calling a “longform story,” I knew it was finally time to read this collection. Ferrante provided, as ever, endless inspiration and comfort: the reminder to trust that, whatever else happens, I just need to write a damn thing I believe in.

I make a point to do a chunk of my reading each year in translation. I read Alba de Céspedes’s The Forbidden Notebook, (translated by Ann Goldstein) which turns the feminist call to “write yourself back into your body” on its head by featuring a mother who, after beginning to write in a diary, goes insane from the self-reflection it requires of her. I got an advanced copy of Vigdis Hjorth’s If Only (translated by Charlotte Barslund), which was unfortunately the same book as Ernaux’s Getting Lost, and the two are perhaps my least favorite of both of their oeuvres. Finally, I did a writing residency in the fall and brought Elena Ferrante’s Frantumaglia (also translated by Goldstein) with me. It was the last of her books I’ve yet to read, perhaps because, if I really love an author, I never like to finish everything they’ve written (this started at an early age—my sister makes fun of me for skipping the fifth season of Buffy so I’d always “have something to look forward to”). But as I set out on what I’m only calling a “longform story,” I knew it was finally time to read this collection. Ferrante provided, as ever, endless inspiration and comfort: the reminder to trust that, whatever else happens, I just need to write a damn thing I believe in.