“When I was twelve,” Larry Levis wrote in “Family Romance,” “I used to stare at weeds / Along the road, at the way they kept trembling / Long after a car had passed.” The narrator watches “gnats in families hovering over / Some rotting peaches, & wonder why it was / I had been born a human. / Why not a weed, or a gnat? / Why not a horse, or a spider?” Levis was a master of such turns, although my favorite practitioner of poetic metamorphosis is Gerard Manley Hopkins. In 1887, Hopkins described Loch Lomond, where the “day was dark and partly hid the lake, yet it did not altogether disfigure it but gave a pensive or solemn beauty which left a deep impression on me.” “Inversnaid,” his poem of that place, follows the churning flow of a burn that is “horseback brown.” The poem’s final stanza arrives as a chant: “What would the world be, once bereft / Of wet and of wildness? Let them be left, / O let them be left, wildness and wet; / Long live the weeds and the wilderness yet.”

“When I was twelve,” Larry Levis wrote in “Family Romance,” “I used to stare at weeds / Along the road, at the way they kept trembling / Long after a car had passed.” The narrator watches “gnats in families hovering over / Some rotting peaches, & wonder why it was / I had been born a human. / Why not a weed, or a gnat? / Why not a horse, or a spider?” Levis was a master of such turns, although my favorite practitioner of poetic metamorphosis is Gerard Manley Hopkins. In 1887, Hopkins described Loch Lomond, where the “day was dark and partly hid the lake, yet it did not altogether disfigure it but gave a pensive or solemn beauty which left a deep impression on me.” “Inversnaid,” his poem of that place, follows the churning flow of a burn that is “horseback brown.” The poem’s final stanza arrives as a chant: “What would the world be, once bereft / Of wet and of wildness? Let them be left, / O let them be left, wildness and wet; / Long live the weeds and the wilderness yet.”

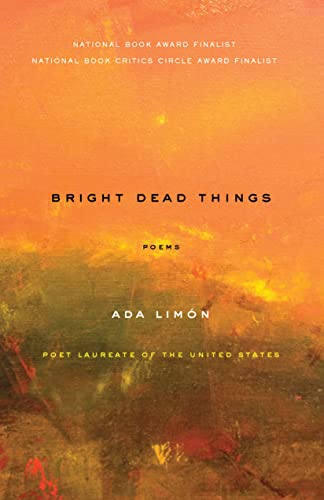

Bright Dead Things, the fourth book of poems by Ada Limón, begins with an epigraph from Levis — “Who among the numberless you have become desires this moment / Which comprehends nothing more than loss & fragility &; the fleeing of flesh” — yet the collection breeds her own particular mixture of wildness. The mixture is by turns melodious and tight. Endemic to a wildness of flee and freedom is a sense of transformation. I think again to Hopkins, who believed that the poetic sense was not merely meant to document the observed world, but that poetry should transform lived reality into a new plane. Limón’s poems are like fires in this way: charring the page, but leaving a smoke that remains past the close of the book.

The narrators — or perhaps singular narrator — of these poems has undergone a transformation from living in Brooklyn to Kentucky. In the prose poem “Mowing,” the narrator watches a man mow “40 acres on a small lawn mower” in slow, hypnotic fashion. “I imagine,” she says, “what it must be like to stay hidden, disappear in the dusky nothing and stay still in the night. It’s not sadness, though it may sound like it.”

The narrator demurs, but there is a curious link between wildness and sadness in the collection. “This land and I are rewilding,” says another narrator. The speakers of these poems lean on the pastoral world for support and rebirth; they are skeptical of God. Yet in “What It Looks Like To Us and the Words We Use,” the narrator plays with the reader’s spiritual sense. “All these great barns out here in the outskirts,” she begins, “black creosote boards knee-deep in the bluegrass. / They look so artfully abandoned, even in use.” Artfully, artifice: “You don’t believe in God?” The narrator doesn’t, but her interlocutor says she is merely mislabeling nature. Still: “we stood there, / low beasts among the white oaks, Spanish moss, / and spider webs, obsidian shards stuck in our pockets, / woodpecker flurry, and I refused to call it so.” Those feelings — doubt, wonder, rejection, flirtation, penance — swirl throughout the book, and are borne of the wildness of self: “I’m cold in my heart, coal-hard / knot in the mountain buried / deep in the boarded-up mine.”

There are also spaces for open hearts in the book, as in the aptly-titled “The Wild Divine.” It’s rare to read a poetics of affirmation — I don’t mean sappy songs, but rather a poet capturing joy, however temporary: “I could barely feel my hands, my limbs numbed / from the new touching that seemed strikingly / natural but also painfully kindled in the body’s stove.” Cue the wildness of Hopkins, for the euphoria that follows love is broken by a “wandering / madrone-skinned horse…bowed-back, higher than a man’s hat, high up / and hitched to nothing.” She thinks: “He seemed almost worthy of complete devotion.” The poem’s ending encapsulates the collection: “I thought, this was what it was to be blessed— / to know a love that was beyond an owning, beyond / the body and its needs, but went straight from wild / thing to wild thing, approving of its wildness.”

Bright Dead Things is an outdoor book, but this is not to say that Limón can’t write a poem about domestic and mundane spaces. “The Good Wave” is an ethereal baseball poem. Other poems sketch homes and apartments (Robert Bly was correct to title one of his collections of poetry essays American Poetry: Wildness and Domesticity). “Nashville After Hours” is a knockout: “Late night in a honky-tonk, fried pickles / in a red plastic basket, and it was all Loretta / on the heel-bruised stage, sung by a big girl / we kind of both had a crush on.” Limón effortlessly narrows the lens of a moment without narrowing its significance. “Good grief we were loaded,” the narrator quips, and in lines that made me long for Elizabeth Tallent’s “Why I Love Country Music,” Limón exits with the perfect breath: “I won’t deny it: I was there, / standing in the bar’s bathroom mirror, / saying my name like I was somebody.”

I look for a healthy tension in a book of poems; call it a scar of being reared on Robert Penn Warren and Allen Tate. The big-sky poems of this book are well-contrasted with heart-skipping narratives like “The Riveter.” The narrator, a manager whose office is in a “high rise,” learns that her mother has a month to live. She “called in my team” for advice about what to do next. Hospice? Total parenteral nutrition? She writes down advice “like this was a meeting / about a client who wasn’t happy,” and soon realizes that the hardest job belonged to her mother, whose work “was to let the machine / of survival break down.” I think of a later poem, “Outside Oklahoma, We See Boston,” that ends “How / masterful and mad is hope.” Madness, wildness, transcendence. Bright Dead Things offers many answers, but is equally appealing for its questions: “Yesterday I was nice, but in truth I resented / the contentment of the field. Why must we practice / this surrender?” May our poems always be wild.