Mentioned in:

A Year in Reading: 2024

Welcome to the 20th (!) installment of The Millions' annual Year in Reading series, which gathers together some of today's most exciting writers and thinkers to share the books that shaped their year. YIR is not a collection of yearend best-of lists; think of it, perhaps, as an assemblage of annotated bibliographies. We've invited contributors to reflect on the books they read this year—an intentionally vague prompt—and encouraged them to approach the assignment however they choose.

In writing about our reading lives, as YIR contributors are asked to do, we inevitably write about our personal lives, our inner lives. This year, a number of contributors read their way through profound grief and serious illness, through new parenthood and cross-country moves. Some found escape in frothy romances, mooring in works of theology, comfort in ancient epic poetry. More than one turned to the wisdom of Ursula K. Le Guin. Many describe a book finding them just when they needed it.

Interpretations of the assignment were wonderfully varied. One contributor, a music critic, considered the musical analogs to the books she read, while another mapped her reads from this year onto constellations. Most people's reading was guided purely by pleasure, or else a desire to better understand events unfolding in their lives or larger the world. Yet others centered their reading around a certain sense of duty: this year one contributor committed to finishing the six Philip Roth novels he had yet to read, an undertaking that he likens to “eating a six-pack of paper towels.” (Lucky for us, he included in his essay his final ranking of Roth's oeuvre.)

The books that populate these essays range widely, though the most commonly noted title this year was Tony Tulathimutte’s story collection Rejection. The work of newly minted National Book Award winner Percival Everett, particularly his acclaimed novel James, was also widely read and written about. And as the genocide of Palestinians in Gaza enters its second year, many contributors sought out Isabella Hammad’s searing, clear-eyed essay Recognizing the Stranger.

Like so many endeavors in our chronically under-resourced literary community, Year in Reading is a labor of love. The Millions is a one-person editorial operation (with an invaluable assist from SEO maven Dani Fishman), and producing YIR—and witnessing the joy it brings contributors and readers alike—has been the highlight of my tenure as editor. I’m profoundly grateful for the generosity of this year’s contributors, whose names and entries will be revealed below over the next three weeks, concluding on Wednesday, December 18. Be sure to subscribe to The Millions’ free newsletter to get the week’s entries sent straight to your inbox each Friday.

—Sophia Stewart, editor

Becca Rothfeld, author of All Things Are Too Small

Carvell Wallace, author of Another Word for Love

Charlotte Shane, author of An Honest Woman

Brianna Di Monda, writer and editor

Nell Irvin Painter, author of I Just Keep Talking

Carrie Courogen, author of Miss May Does Not Exist

Ayşegül Savaş, author of The Anthropologists

Zachary Issenberg, writer

Tony Tulathimutte, author of Rejection

Ann Powers, author of Traveling: On the Path of Joni Mitchell

Lidia Yuknavitch, author of Reading the Waves

Nicholas Russell, writer and critic

Daniel Saldaña París, author of Planes Flying Over a Monster

Lili Anolik, author of Didion and Babitz

Deborah Ghim, editor

Emily Witt, author of Health and Safety

Nathan Thrall, author of A Day in the Life of Abed Salama

Lena Moses-Schmitt, author of True Mistakes

Jeremy Gordon, author of See Friendship

John Lee Clark, author of Touch the Future

Ellen Wayland-Smith, author of The Science of Last Things

Edwin Frank, publisher and author of Stranger Than Fiction

Sophia Stewart, editor of The Millions

A Year in Reading Archives: 2023, 2022, 2021, 2020, 2019, 2018, 2017, 2016, 2015, 2014, 2013, 2011, 2010, 2009, 2008, 2007, 2006, 2005

The Great Fall 2024 Book Preview

With the arrival of autumn comes a deluge of great books. Here you'll find a sampling of new and forthcoming titles that caught our eye here at The Millions, and that we think might catch yours, too. Some we’ve already perused in galley form; others we’re eager to devour based on their authors, plots, or subject matters. We hope your next fall read is among them.

—Sophia Stewart, editor

October

Season of the Swamp by Yuri Herrera, tr. Lisa Dillman [F]

What it is: An epic, speculative account of the 18 months that Benito Juárez spent in New Orleans in 1853-54, years before he became the first and only Indigenous president of Mexico.

Who it's for: Fans of speculative history; readers who appreciate the magic that swirls around any novel set in New Orleans. —Claire Kirch

The Black Utopians by Aaron Robertson [NF]

What it is: An exploration of Black Americans' pursuit and visions of utopia—both ideological and physical—that spans the Reconstruction era to the present day and combines history, memoir, and reportage.

Who it's for: Fans of Saidiya Hartman's Wayward Lives, Beautiful Experiments and Kristen R. Ghodsee's Everyday Utopia. —Sophia M. Stewart

The Third Realm by Karl Ove Knausgaard, tr. Martin Aitken [F]

What it is: The third installment in Knausgaard's Morning Star series, centered on the appearance of a mysterious new star in the skies above Norway.

Who it's for: Real Knausgaard heads only—The Wolves of Eternity and Morning Star are required reading for this one. —SMS

Brown Women Have Everything by Sayantani Dasgupta [NF]

What it is: Essays on the contradictions and complexities of life as an Indian woman in America, probing everything from hair to family to the joys of travel.

Who it's for: Readers of Durga Chew-Bose, Erika L. Sánchez, and Tajja Isen. —SMS

The Plot Against Native America by Bill Vaughn [F]

What it is: The first narrative history of Native American boarding schools— which aimed "civilize" Indigenous children by violently severing them from their culture— and their enduring, horrifying legacy.

Who it's for: Readers of Ned Blackhawk and Kathleen DuVal. —SMS

The Mighty Red by Louise Erdrich [F]

What it is: Erdrich's latest novel set in North Dakota's Red River Valley is a tale of the intertwined lives of ordinary people striving to survive and even thrive in their rural community, despite environmental upheavals, the 2008 financial crisis, and other obstacles.

Who it's for: Readers of cli-fi; fans of Linda LeGarde Grover and William Faulkner. —CK

The Position of Spoons by Deborah Levy [NF]

What it is: The second book from Levy in as many years, diverging from a recent streak of surrealist fiction with a collection of essays marked by exceptional observance and style.

Who it's for: Close lookers and the perennially curious. —John H. Maher

The Bog Wife by Kay Chronister [F]

What it's about: The Haddesley family has lived on the same West Virginia bog for centuries, making a supernatural bargain with the land—a generational blood sacrifice—in order to do so—until an uncovered secret changes everything.

Who it's for: Readers of Karen Russell and Jeff VanderMeer; anyone who has ever used the phrase "girl moss." —SMS

The Great When by Alan Moore [F]

What it's about: When an 18-year old book reseller comes across a copy of a book that shouldn’t exist, it threatens to upend not just an already post-war-torn London, but reality as we know it.

Who it's for: Anyone looking for a Sherlock Holmes-style mystery dipped in thaumaturgical psychedelia. —Daniella Fishman

The Message by Ta-Nehisi Coates [NF]

What it's about: One of our sharpest critical thinkers on social justice returns to nonfiction, nearly a decade after Between the World and Me, visiting Dakar, to contemplate enslavement and the Middle Passage; Columbia, S.C., as a backdrop for his thoughts on Jim Crow and book bans; and the Israeli-occupied West Bank, where he sees contemporary segregation in the treatment of Palestinians.

Who it’s for: Fans of James Baldwin, George Orwell, and Angela Y. Davis; readers of Nikole Hannah-Jones’s The 1619 Project and Isabel Wilkerson’s Caste, to name just a few engagements with national and racial identity. —Nathalie op de Beeck

Abortion by Jessica Valenti [NF]

What it is: Columnist and memoirist Valenti, who tracks pro-choice advocacy and attacks on the right to choose in her Substack, channels feminist rage into a guide for freedom of choice advocacy.

Who it’s for: Readers of Robin Marty’s The New Handbook for a Post-Roe America, #ShoutYourAbortion proponents, and followers of Jennifer Baumgartner’s [I Had an Abortion] project. —NodB

Gifted by Suzuki Suzumi, tr. Allison Markin Powell [F]

What it's about: A young sex worker in Tokyo's red-light district muses on her life and recounts her abusive mother's final days, in what is Suzuki's first novel to be translated into English.

Who it's for: Readers of Susan Boyt and Mieko Kanai; fans of moody, introspective fiction; anyone with a fraught relationship to their mother. —SMS

Childish Literature by Alejandro Zambra, tr. Megan McDowell [F]

What it is: A wide-ranging collection of stories, essays, and poems that explore childhood, fatherhood, and family.

Who it's for: Fans of dad lit (see: Lucas Mann's Attachments, Keith Gessen's Raising Raffi, Karl Ove Knausgaard's seasons quartet, et al). —SMS

Books Are Made Out of Books ed. Michael Lynn Crews [NF]

What it is: A mining of the archives of the late Cormac McCarthy with a focus on the famously tight-lipped author's literary influences.

Who it's for: Anyone whose commonplace book contains the words "arquebus," "cordillera," or "vinegaroon." —JHM

Slaveroad by John Edgar Wideman [F]

What it is: A blend of memoir, fiction, and history that charts the "slaveroad" that runs through American history, spanning the Atlantic slave trade to the criminal justice system, from the celebrated author of Brothers and Keepers.

Who it's for: Fans of Clint Smith and Ta-Nehisi Coates. —SMS

Linguaphile by Julie Sedivy [NF]

What it's about: Linguist Sedivy reflects on a life spent loving language—its beauty, its mystery, and the essential role it plays in human existence.

Who it's for: Amateur (or professional) linguists; fans of the podcast A Way with Words (me). —SMS

An Image of My Name Enters America by Lucy Ives [NF]

What it is: A collection of interrelated essays that connect moments from Ives's life to larger questions of history, identity, and national fantasy,

Who it's for: Fans of Ives, one of our weirdest and most wondrous living writers—duh; anyone with a passing interest in My Little Pony, Cold War–era musicals, or The Three Body Problem, all of which are mined here for great effect. —SMS

Women's Hotel by Daniel Lavery [F]

What it is: A novel set in 1960s New York City, about the adventures of the residents of a hotel providing housing for young women that is very much evocative of the real-life legendary Barbizon Hotel.

Who it's for: Readers of Mary McCarthy's The Group and Rona Jaffe's The Best of Everything. —CK

The World in Books by Kenneth C. Davis [NF]

What it is: A guide to 52 of the most influential works of nonfiction ever published, spanning works from Plato to Ida B. Wells, bell hooks to Barbara Ehrenreich, and Sun Tzu to Joan Didion.

Who it's for: Lovers of nonfiction looking to cover their canonical bases. —SMS

Blue Light Hours by Bruna Dantas Lobato [F]

What it's about: Through the emanating blue-glow of their computer screens, a mother and daughter, four-thousand miles apart, find solace and loneliness in their nightly Skype chats in this heartstring-pulling debut.

Who it's for: Someone who needs to be reminded to CALL YOUR MOTHER! —DF

Riding Like the Wind by Iris Jamahl Dunkle [NF]

What it is: The biography of Sanora Babb, a contemporary of John Steinbeck's whose field notes and interviews with Dust Bowl migrants Steinbeck relied upon to write The Grapes of Wrath.

Who it's for: Steinbeck fans and haters alike; readers of Kristin Hannah's The Four Winds and the New York Times Overlooked column; anyone interested in learning more about the Dust Bowl migrants who fled to California hoping for a better life. —CK

Innie Shadows by Olivia M. Coetzee [F]

What it is: a work of crime fiction set on the outskirts of Cape Town, where a community marred by violence seeks justice and connection; also the first novel to be translated from Kaaps, a dialect of Afrikaans that was until recently only a spoken language.

Who it's for: fans of sprawling, socioeconomically-attuned crime dramas a la The Wire. —SMS

Dorothy Parker in Hollywood by Gail Crowther [NF]

What it is: A history of the famous wit—and famous New Yorker—in her L.A. era, post–Algonquin Round Table and mid–Red Scare.

Who it's for: Owners of a stack of hopelessly dog-eared Joan Didion paperbacks. —JHM

The Myth of American Idealism by Noam Chomsky and Nathan J. Robinson [NF]

What it is: A potent critique of the ideology behind America's foreign interventions and its status as a global power, and an treatise on how the nation's hubristic pursuit of "spreading democracy" threatens not only the delicate balance of global peace, but the already-declining health of our planet.

Who it's for: Chomskyites; policy wonks and casual critics of American recklessness alike. —DF

Mysticism by Simon Critchley [NF]

What it is: A study of mysticism—defined as an experience, rather than religious practice—by the great British philosopher Critchley, who mines music, poetry, and literature along the way.

Who it's for: Readers of John Gray, Jorge Luis Borges, and Simone Weil. —SMS

Q&A by Adrian Tomine [NF]

What it is: The Japanese American creator of the Optic Nerve comic book series for D&Q, and of many a New Yorker cover, shares his personal history and his creative process in this illustrated unburdening.

Who it’s for: Readers of Tomine’s melancholic, sometimes cringey, and occasionally brutal collections of comics short stories including Summer Blonde, Shortcomings, and Killing and Dying. —NodB

Sonny Boy by Al Pacino [NF]

What it is: Al Pacino's memoir—end of description.

Who it's for: Cinephiles; anyone curious how he's gonna spin fumbling Diane Keaton. —SMS

Seeing Baya by Alice Kaplan [NF]

What it is: The first biography of the enigmatic and largely-forgotten Algerian artist Baya Mahieddine, who first enchanted midcentury Paris as a teenager.

Who it's for: Admirers of Leonora Carrington, Hilma af Klint, Frida Kahlo, and other belatedly-celebrated women painters. —SMS

Absolution by Jeff VanderMeer [F]

What it is: A surprise return to the Area X, the stretch of unforbidding and uncanny coastline in the hit Southern Reach trilogy.

Who it's for: Anyone who's heard this song and got the reference without Googling it. —JHM

The Four Horsemen by Nick Curtola [NF]

What it is: The much-anticipated cookbook from the team behind Brooklyn's hottest restaurant (which also happens to be co-owned by James Murphy of LCD Soundsystem).

Who it's for: Oenophiles; thirty-somethings who live in north Williamsburg (derogatory). —SMS

Seeing Further by Esther Kinsky, tr. Caroline Schmidt [F]

What it's about: An unnamed German woman embarks on the colossal task of reviving a cinema in a small Hungarian village.

Who it's for: Fans of Jenny Erpenbeck; anyone charmed by Cinema Paradiso (not derogatory!). —SMS

Ripcord by Nate Lippens [NF]

What it's about: A novel of class, sex, friendship, and queer intimacy, written in delicious prose and narrated by a gay man adrift in Milwaukee.

Who it's for: Fans of Brontez Purnell, Garth Greenwell, Alexander Chee, and Wayne Koestenbaum. —SMS

The Use of Photography by Annie Ernaux and Marc Marie, tr. Alison L. Strayer [NF]

What it's about: Ernaux's love affair with Marie, a journalist, while she was undergoing treatment for cancer, and their joint project to document their romance.

Who it's for: The Ernaux hive, obviously; readers of Sontag's On Photography and Janet Malcolm's Still Pictures. —SMS

Nora Ephron at the Movies by Ilana Kaplan [NF]

What it is: Kaplan revisits Nora Ephron's cinematic watersheds—Silkwood, Heartburn, When Harry Met Sally, You've Got Mail, and Sleepless in Seattle—in this illustrated book. Have these iconic stories, and Ephron’s humor, weathered more than 40 years?

Who it’s for: Film history buffs who don’t mind a heteronormative HEA; listeners of the Hot and Bothered podcast; your coastal grandma. —NodB

[millions_email]

The Philosophy of Translation by Damion Searls [NF]

What it is: A meditation on the act and art of translation by one of today's most acclaimed practitioners, best known for his translations of Fosse, Proust, et al.

Who it's for: Regular readers of Words Without Borders and Asymptote; professional and amateur literary translators alike. —SMS

Salvage by Dionne Brand

What it is: A penetrating reevaluation of the British literary canon and the tropes once shaped Brand's reading life and sense of self—and Brand’s first major work of nonfiction since her landmark A Map to the Door of No Return.

Who it's for: Readers of Christina Sharpe's Ordinary Notes and Elizabeth Hardwick's Seduction and Betrayal. —SMS

Masquerade by Mike Fu [F]

What it's about: Housesitting for an artist friend in present-day New York, Meadow Liu stumbles on a novel whose author shares his name—the first of many strange, haunting happenings that lead up to the mysterious disappearance of Meadow's friend.

Who it's for: fans of Ed Park and Alexander Chee. —SMS

November

The Beggar Student by Osamu Dazai, tr. Sam Bett [F]

What it is: A novella in the moody vein of Dazai’s acclaimed No Longer Human, following the 30-something “fictional” Dazai into another misadventure spawned from a hubristic spat with a high schooler.

Who it's for: Longtime readers of Dazai, or new fans who discovered the midcentury Japanese novelist via TikTok and the Bungo Stray Dogs anime. —DF

In Thrall by Jane DeLynn [F]

What it is: A landmark lesbian bildungsroman about 16-year-old Lynn's love affair with her English teacher, originally published in 1982.

Who it's for: Fans of Joanna Russ's On Strike Against God and Edmund White's A Boy's Own Story —SMS

Washita Love Child by Douglas Kent Miller [NF]

What it is: The story of Jesse Ed Davis, the Indigenous musician who became on of the most sought after guitarists of the late '60s and '70s, playing alongside B.B. King, Bob Dylan, John Lennon, and more.

Who it's for: readers of music history and/or Indigenous history; fans of Joy Harjo, who wrote the foreword. —SMS

Set My Heart on Fire by Izumi Suzuki, tr. Helen O'Horan [F]

What it is: Gritty, sexy, and wholly rock ’n’ roll, Suzuki’s first novel translated into English (following her story collection, Hit Parade of Tears) follows 20-year-old Izumi navigating life, love, and music in the underground scene in '70s Japan.

Who it's for: Fans of Meiko Kawakami, Ursula K. Le Guin, and Marlowe Granados's Happy Hour. —DF

Didion & Babitz by Lili Anolik [NF]

What it is: A dual portrait of Joan Didion and Eve Babitz, who are so often compared to—and pitted against—each other on the basis of their mutual Los Angeles milieu.

Who it's for: Fans or haters of either writer (the book is fairly pro-Babitz, often at Didion's expense); anyone who has the Lit Hub Didion tote bag. —SMS

The Endless Refrain by David Rowell [NF]

What it's about: How the rise of music streaming, demonitizing of artist revenue, and industry tendency toward nostalgia have laid waste to the musical landscape, and the future of music culture.

Who it's for: Fans of Kyle Chayka, Spence Kornhaber, and Lindsay Zoladz. —SMS

Every Arc Bends Its Radian by Sergio De La Pava [F]

What it is: A mind- and genre-bending detective story set in Cali, Colombia, that blends high-stakes suspense with rigorous philosophy.

Who it's for: Readers of Raymond Chandler, Thomas Pynchon, and Jules Verne. —SMS

Something Close to Nothing by Tom Pyun [F]

What it’s about: At the airport with his white husband Jared, awaiting a flight to Cambodia to meet the surrogate mother carrying their adoptive child-to-be, Korean American Wynn decides parenthood isn't for him, and bad behavior ensues.

Who it’s for: Pyun’s debut is calculated to cut through saccharine depictions of queer parenthood—could pair well with Torrey Peters’s Detransition, Baby. —NodB

Rosenfeld by Maya Kessler [F]

What it is: Kessler's debut—rated R for Rosenfeld—follows one Noa Simmons through the tumultuous and ultimately profound power play that is courting (and having a lot of sex with) the titular older man who soon becomes her boss.

Who it's for: Fans of Sex and the City, Raven Leilani’s Luster, and Coco Mellor’s Cleopatra and Frankenstein. —DF

Lazarus Man by Richard Price [F]

What it is: The former The Wire writer offers yet another astute chronicle of urban life, this time of an ever-changing Harlem.

Who it's for: Fans of Colson Whitehead's Crook Manifesto and Paul Murray's The Bee Sting—and, of course, The Wire. —SMS

Stranger Than Fiction by Edwin Frank [NF]

What it is: An astute curveball of a read on the development and many manifestations of the novel throughout the tumultuous 20th century.

Who it's for: Readers who look at a book's colophon before its title. —JHM

Letters to His Neighbor by Marcel Proust, tr. Lydia Davis

What it is: A collection of Proust’s tormented—and frequently hilarious—letters to his noisy neighbor which, in a diligent translation from Davis, stand the test of time.

Who it's for: Proust lovers; people who live below heavy-steppers. —DF

Context Collapse by Ryan Ruby [NF]

What it is: A self-proclaimed "poem containing a history of poetry," from ancient Greece to the Iowa Workshop, from your favorite literary critic's favorite literary critic.

Who it's for: Anyone who read and admired Ruby's titanic 2022 essay on The Waste Land; lovers of poetry looking for a challenge. —SMS

How Sondheim Can Change Your Life by Richard Schoch [NF]

What it's about: Drama professor Schoch's tribute to Stephen Sondheim and the life lessons to be gleaned from his music.

Who it's for: Sondheim heads, former theater kids, end of list. —SMS

The Serviceberry by Robin Wall Kimmerer [NF]

What it is: 2022 MacArthur fellow and botanist Kimmerer, an enrolled member of the Citizen Potawatomi Nation, (re)introduces audiences to a flowering, fruiting native plant beloved of foragers and gardeners.

Who it’s for: The restoration ecologist in your life, along with anyone who loved Braiding Sweetgrass and needs a nature-themed holiday gift. —NodB

My Heart Belongs in an Empty Big Mac Container Buried Beneath the Ocean Floor by Homeless [F]

What it is: A pseudonymous, tenderly comic novel of blue whales and Golden Arches, mental illness and recovery.

Who it's for: Anyone who finds Thomas Pynchon a bit too staid. —JHM

Yoke and Feather by Jessie van Eerden [NF]

What it's about: Van Eerden's braided essays explore the "everyday sacred" to tease out connections between ancient myth and contemporary life.

Who it's for: Readers of Courtney Zoffness's Spilt Milk and Jeanna Kadlec's Heretic. —SMS

Camp Jeff by Tova Reich [F]

What it's about: A "reeducation" center for sex pests in the Catskills, founded by one Jeffery Epstein (no, not that one), where the dual phenomena of #MeToo and therapyspeak collide.

Who it's for: Fans of Philip Roth and Nathan Englander; cancel culture skeptics. —SMS

Selected Amazon Reviews by Kevin Killian [NF]

What it is: A collection of 16 years of Killian’s funniest, wittiest, and most poetic Amazon reviews, the sheer number of which helped him earn the rarefied “Top 100” and “Hall of Fame” status on the site.

Who it's for: Fans of Wayne Koestenbaum and Dodie Bellamy, who wrote introduction and afterword, respectively; people who actually leave Amazon reviews. —DF

Cher by Cher [NF]

What it is: The first in a two-volume memoir, telling the story of Cher's early life and ascendent career as only she can tell it.

Who it's for: Anyone looking to fill the My Name Is Barbra–sized hole in their heart, or looking for something to tide them over until the Liza memoir drops. —SMS

The City and Its Uncertain Walls by Haruki Murakami, tr. Philip Gabriel [F]

What it is: Murakami’s first novel in over six years returns to the high-walled city from his 1985 story "Hard-Boiled Wonderland and the End of the World" with one man's search for his lost love—and, simultaneously, an ode to libraries and literature itself.

Who it's for: Murakami fans who have long awaited his return to fiction. —DF

American Bulk by Emily Mester [NF]

What it's about: Reflecting on what it means to "live life to the fullest," Mester explores the cultural and personal impacts of America’s culture of overconsumption, from Costco hauls to hoarding to diet culture—oh my!

Who it's for: Lovers of sustainability; haters of excess; skeptics of the title essay of Becca Rothfeld's All Things Are Too Small. —DF

The Icon and the Idealist by Stephanie Gorton [NF]

What it is: A compelling look at the rivalry between Margaret Sanger, of Planned Parenthood fame, and Mary Ware Dennett, who each held radically different visions for the future of birth control.

Who it's for: Readers of Amy Sohn's The Man Who Hated Women and Katherine Turk's The Women of NOW; anyone interested in the history of reproductive rights. —SMS

December

Rental House by Weike Wang [F]

What it's about: Married college sweethearts invite their drastically different families on a Cape Code vacation, raising questions about marriage, intimacy, and kinship.

Who it's for: Fans of Wang's trademark wit and sly humor (see: Joan Is Okay and Chemistry); anyone with an in-law problem.

Woo Woo by Ella Baxter [F]

What it's about: A neurotic conceptual artist loses her shit in the months leading up to an exhibition that she hopes will be her big breakout, poking fun at the tropes of the "art monster" and the "woman of the verge" in one fell, stylish swoop.

Who it's for: Readers of Sheena Patel's I'm a Fan and Chris Kraus's I Love Dick; any woman who is grateful to but now also sort of begrudges Jenny Offil for introducing "art monster" into the lexicon (me). —SMS

Berlin Atomized by Julia Kornberg, tr. Jack Rockwell and Julia Kornberg [F]

What it's about: Spanning 2001 to 2034, three Jewish and downwardly mobile siblings come of age in various corners of the world against the backdrop of global crisis.

Who it's for: Fans of Catherine Lacey's Biography of X and Joshua Cohen's The Netanyahus. —SMS

Sand-Catcher by Omar Khalifah, tr. Barbara Romaine [F]

What it is: A suspenseful, dark satire of memory and nation, in which four young Palestinian journalists at a Jordanian newspaper are assigned to interview an elderly witness to the Nakba, the violent 1948 expulsion of native Palestinians from Israel—but to their surprise, the survivor doesn’t want to rehash his trauma for the media.

Who it’s for: Anyone looking insight—tinged with grim humor—into the years leading up to the present political crisis in the Middle East and the decades-long goal of Palestinian autonomy. —NodB

The Shutouts by Gabrielle Korn [F]

What it's about: In the dystopian future, mysteriously connected women fight to survive on the margins of society amid worsening climate collapse.

Who it's for: Fans of Korn's Yours for the Taking, which takes place in the same universe; readers of Becky Chambers and queer-inflected sci-fi. —SMS

What in Me Is Dark by Orlando Reade [NF]

What it's about: The enduring, evolving influence of Milton's Paradise Lost on political history—and particularly on the work of 12 revolutionary readers, including Malcom X and Hannah Arendt.

Who it's for: English majors and fans of Ryan Ruby and Sarah Bakewell—but I repeat myself. —SMS

The Afterlife Is Letting Go by Brandon Shimoda [NF]

What it's about: Shimoda researches the mass incarceration of Japanese Americans during WWII, and speaks with descendants of those imprisoned, for this essay collection about the “afterlife” of cruelty and xenophobia in the U.S.

Who it’s for: Anyone to ever visit a monument, museum, or designated site of hallowed ground where traumatic events have taken place. —NodB

No Place to Bury the Dead by Karina Sainz Borgo, tr. Elizabeth Bryer [F]

What it's about: When Angustias Romero loses both her children while fleeing a mysterious disease in her unnamed Latin American country, she finds herself in a surreal, purgatorial borderland where she's soon caught in a power struggle.

Who it's for: Fans of Maríana Enriquez and Mohsin Hamid. —SMS

The Rest Is Silence by Augusto Monterroso, tr. Aaron Kerner [F]

What it is: The author of some of the shortest, and tightest, stories in Latin American literature goes long with a metafictional skewering of literary criticism in his only novel.

Who it's for: Anyone who prefers the term "palm-of-the-hand stories" to "flash fiction." —JHM

Tali Girls by Siamak Herawi, tr. Sara Khalili [F]

What it is: An intimate, harrowing, and vital look at the lives of girls and women in an Afghan mountain village under Taliban rule, based on true stories.

Who it's for: Readers of Nadia Hashimi, Akwaeke Emezi, and Maria Stepanova. —SMS

Sun City by Tove Jansson, tr. Thomas Teal [F]

What it's about: During her travels through the U.S. in the 1970s, Jansson became interested in the retirement home as a peculiarly American institution—here, she imagines the tightly knit community within one of them.

Who it's for: Fans of Jansson's other fiction for adults, much of which explores the lives of elderly folks; anyone who watched that documentary about The Villages in Florida. —SMS

Editor's note: We're always looking to make our seasonal book previews more useful to the readers, writers, and critics they're meant to serve. Got an idea for how we can improve our coverage? Tell me about it at sophia@themillions.com.

[millions_email]

Literary Curveball

When most baseball players retire, they manage other teams, but Derek Jeter will manage a publishing imprint. The shortstop will open a publishing company, Jeter Publishing, in a partnership with Simon & Schuster. He expects to publish middle-grade fiction, children's picture books, adult nonfiction, and books for children learning how to read. The first title should hit shelves in 2014. Maybe this could have been a good backup career for The Art of Fielding's Henry Skrimshander.

Game Theory

Recommended: Art of Fielding author Chad Harbach on sports novels.

The Point of the Paperback

1.

“Why are they still bothering with paperbacks?” This came from a coffee-shop acquaintance when he heard my book was soon to come out in paperback, nine months after its hardcover release. “Anyone who wants it half price already bought it on ebook, or Amazon.”

Interestingly, his point wasn’t the usual hardcovers-are-dead-long-live-the-hardcover knell. To his mind, what was the use of a second, cheaper paper version anymore, when anyone who wanted it cheaply had already been able to get it in so many different ways?

I would have taken issue with his foregone conclusion about the domination of ebooks over paper, but I didn’t want to spend my babysitting time down that rabbit hole. But he did get me thinking about the role of the paperback relaunch these days, and how publishers go about getting attention for this third version of a novel — fourth, if you count audiobooks.

I did what I usually do when I’m puzzling through something, which is to go back to my journalism-school days and report on it. Judging by the number of writers who asked me to share what I heard, there are a good number of novelists who don’t quite know what to do with their paperbacks, either.

Here’s what I learned, after a month of talking to editors, literary agents, publishers, and other authors: A paperback isn’t just a cheaper version of the book anymore. It’s a makeover. A facelift. And for some, a second shot.

2.

About ebooks. How much are they really cutting into print, both paperbacks and hardcovers? Putting aside the hype and the crystal ball, how do the numbers really look?

The annual Bookstats Report from the Association of American Publishers (AAP), which collects data from 1,977 publishers, is one of the most reliable measures. In the last full report — which came out July 2012 — ebooks outsold hardcovers for the first time, representing $282.3 million in sales (up 28.1%), compared to adult hardcover ($229.6 million, up 2.7%). But not paperback — which, while down 10.5%, still represented $299.8 million in sales. The next report comes out this July, and it remains to be seen whether ebook sales will exceed paper. Monthly stat-shots put out by the AAP since the last annual report show trade paperbacks up, but the group’s spokesperson cautioned against drawing conclusions from interim reports rather than year-end numbers.

Numbers aside, do we need to defend whether the paperback-following-hardcover still has relevance?

“I think that as opposed to a re-release being less important, it’s more than ever important because it gives a book a second chance with a new cover and lower cost, plus you can use all the great reviews the hardcover got,” says MJ Rose, owner of the book marketing firm Authorbuzz, as well as a bestselling author of novels including The Book of Lost Fragrances. “So many books sell 2,000 or 3,000 copies in hardcover and high-priced ebooks, but take off when they get a second wind from trade paperback and their e-book prices drop.”

What about from readers’ perspectives? Is there something unique about the paperback format that still appeals?

I put the question to booksellers, though of course as bricks-and-mortar sellers, it’s natural that they would have a bias toward paper. Yet the question isn’t paper versus digital: it’s whether they are observing interest in a paper book can be renewed after it has already been out for nine months to a year, and already available at the lower price, electronically.

“Many people still want the portability of a lighter paper copy,” said Deb Sundin, manager of Wellesley Books in Wellesley, MA. “They come in before vacation and ask, ‘What’s new in paper?’ ”

“Not everyone e-reads,” says Nathan Dunbar, a manager at Barnes & Noble in Skokie, IL. “Many customers tell us they’ll wait for the paperback savings. Also, more customers will casually pick up the paperback over hardcover.”

Then there’s the issue of what a new cover can do. “For a lot of customers the paperback is like they’re seeing it for the first time,” says Mary Cotton, owner of Newtonville Books in Newtonvillle, MA. “It gives me an excuse to point it out to people again as something fresh and new, especially if it has a new cover.”

3.

A look at a paperback’s redesign tells you a thing or two about the publisher’s mindset: namely, whether or not the house believes the book has reached its intended audience, and whether there’s another audience yet to reach. Beyond that, it’s anyone’s Rorschach. Hardcovers with muted illustrations morph into pop art, and vice versa. Geometric-patterned book covers are redesigned with nature imagery; nature imagery in hardcover becomes photography of women and children in the paperback. Meg Wolitzer, on a panel about the positioning of women authors at the recent AWP conference, drew knowing laughter for a reference to the ubiquitous covers with girls in a field or women in water. Whether or not publishers want to scream book club, they at least want to whisper it.

“It seems that almost every book these days gets a new cover for the paperback. It’s almost as if they’re doing two different books for two different audiences, with the paperback becoming the ‘book club book,’” says Melanie Benjamin, author of The Aviator’s Wife. Benjamin watched the covers of her previous books, including Mrs. Tom Thumb and Alice I Have Been, change from hardcovers that were “beautiful, and a bit brooding” to versions that were “more colorful, more whimsical.”

A mood makeover is no accident, explains Sarah Knight, a senior editor at Simon & Schuster, and can get a paperback ordered in a store that wouldn’t be inclined to carry its hardcover. “New cover art can re-ignite interest from readers who simply passed the book over in hardcover, and can sometimes help get a book displayed in an account that did not previously order the hardcover because the new art is more in line with its customer base.” Some stores, like the big-boxes and airports, also carry far more paperbacks than hardcovers. Getting into those aisles in paperback can have an astronomical effect on sales.

An unscientific look at recent relaunches shows a wide range of books that got full makeovers: Olive Kitteridge, A Visit From the Goon Squad, The Newlyweds, The Language of Flowers, The Song Remains the Same, The Age of Miracles, Arcadia, and The Unlikely Pilgrimage of Harold Fry, as did my own this month (The Unfinished Work of Elizabeth D.)

Books that stayed almost completely the same, plus or minus a review quote and accent color, include Wild, Beautiful Ruins, The Snow Child, The Weird Sisters, The Paris Wife, Maine, The Marriage Plot, The Art of Fielding, The Tiger’s Wife, Rules of Civility, and The Orchardist.

Most interesting are the books that receive the middle-ground treatment, designers flirting with variations on their iconic themes. The Night Circus, The Invisible Bridge, State of Wonder, The Lifeboat, Billy Lynn’s Long Halftime Walk, Tell the Wolves I’m Home, Tigers in Red Weather, and The Buddha in the Attic are all so similar to the original in theme or execution that they’re like a wink to those in the know — and pique the memory of those who have a memory of wanting to read it the first time around.

Some writers become attached to their hardcovers and resist a new look in paperback. Others know it’s their greatest chance of coming out of the gate a second time — same race, fresh horse.

When Jenna Blum’s first novel, Those Who Save Us, came out in hardcover in 2004, Houghton Mifflin put train tracks and barbed wire on the cover. Gorgeous, haunting, and appropriate for a WWII novel, but not exactly “reader-friendly,” Blum recalls being told by one bookseller. The following year, the paperback cover — a girl in a bright red coat in front of a European bakery — telegraphed the novel’s Holocaust-era content without frightening readers away.

“The paperback cover helped save the book from the remainder bins, I suspect,” Blum says.

Armed with her paperback, Jenna went everywhere she was invited, which ended up tallying more than 800 book clubs. Three years later, her book hit the New York Times bestseller list.

“Often the hardcover is the friends-and-family edition, because that’s who buys it, in addition to collectors,” she says. “It’s imperative that a paperback give the novel a second lease on life if the hardcover didn’t reach all its intended audience, and unless you are Gillian Flynn, it probably won’t.”

There’s no hard-and-fast rule about when the paperback should ride in for that second lease. A year to paperback used to be standard, but now a paperback can release earlier — to capitalize on a moderately successful book before it’s forgotten — or later, if a hardcover is still turning a strong profit.

At issue: the moment to reissue, and the message to send.

“Some books slow down at a point, and the paperback is a great opportunity to repromote and reimagine,” says Sheila O’Shea, associate publisher for Broadway and Hogarth paperbacks at the Crown Publishing Group (including, I should add, mine). “The design of a paperback is fascinating, because you have to get it right in a different way than the hardcover. If it’s a book that relates specifically to females you want that accessibility at the table — women drawn in, wondering, Ooh, what’s that about.”

The opportunity to alter the message isn’t just for cover design, but the entire repackaging of the book — display text, reviews put on the jacket, synopses used online, and more. In this way, the paperback is not unlike the movie trailer which, when focus-grouped, can be reshaped to spotlight romantic undertones or a happy ending.

“Often by the time the paperback rolls around, both the author and publicist will have realized where the missed opportunities were for the hardcover, and have a chance to correct that,” says Simon & Schuster’s Sarah Knight. “Once your book has been focus-grouped on the biggest stage — hardcover publication — you get a sense of the qualities that resonate most with people, and maybe those were not the qualities you originally emphasized in hardcover. So you alter the flap copy, you change the cover art to reflect the best response from the ideal readership, and in many cases, the author can prepare original material to speak to that audience.”

Enter programs like P.S. (Harper Collins) and Extra Libris (Crown Trade and Hogarth), with new material in the back such as author interviews, essays, and suggested reading lists.

“We started Extra Libris last spring to create more value in the paperback, to give the author another opportunity to speak to readers. We had been doing research with booksellers and our reps and book club aficionados asking, What would you want in paperbacks? And it’s always extra content,” says Crown’s O’Shea. “Readers are accustomed to being close to the content and to the authors. It’s incumbent on us to have this product to continue the conversation.”

4.

Most of a paperback discussion centers on the tools at a publisher’s disposal, because frankly, so much of a book’s success is about what a publisher can do — from ads in trade and mainstream publications, print and online, to talking up the book in a way that pumps enthusiasm for the relaunch. But the most important piece is how, and whether, they get that stack in the store.

My literary agent Julie Barer swears the key to paperback success is physical placement. “A big piece of that is getting stores (including the increasingly important Costco and Target) to take large orders, and do major co-op. I believe one of the most important things that moves books is that big stack in the front of the store,” she says. “A lot of that piece is paid for and lobbied for by the publisher.”

Most publicists’ opportunities for reviews have come and gone with the hardcover, but not all, says Kathleen Zrelak Carter, a partner with the literary PR firm Goldberg McDuffie. “A main factor for us in deciding whether or not to get involved in a paperback relaunch is the off-the-book-page opportunities we can potentially pursue. This ranges from op-ed pieces to essays and guest blog posts,” she says. “It’s important for authors to think about all the angles in their book, their research and inspiration, but also to think about their expertise outside of being a writer, and how that can be utilized to get exposure.”

What else can authors do to support the paperback launch?

Readings have already been done in the towns where they have most connections, and bookstores don’t typically invite authors to come for a paperback relaunch. But many are, however, more than happy to have relaunching authors join forces with an author visiting for a new release, or participate in a panel of authors whose books touch on a common theme.

And just because a bookstore didn’t stock a book in hardcover doesn’t mean it won’t carry the paperback. Having a friend or fellow author bring a paperback to the attention of their local bookseller, talking up its accolades, can make a difference.

I asked folks smarter than I about branding, and they said the most useful thing for authors receiving a paperback makeover is to get on board with the new cover. That means fronting the new look everywhere: the author website, Facebook page, and Twitter. Change the stationery and business cards too if, like I did, you made them all about a cover that is no longer on the shelf.

“Sometimes a writer can feel, ‘But I liked this cover!’” says Crown’s O’Shea. “It’s important to be flexible about the approach, being open to the idea of reimagining your own work for a broader audience, and using the tools available to digitally promote the book with your publisher.”

More bluntly said, You want to sell books? Get in the game. Your hardcover might have come and gone, but in terms of your book’s rollout, it’s not even halftime yet.

“The paperback is truly a new release, and a smart author will treat it as such,” says Randy Susan Meyers, author The Murderer’s Daughters, her new novel The Comfort Of Lies, and co-author of the publishing-advice book What To Do Before Your Book Launch with book marketer and novelist M.J. Rose. “Make new bookmarks, spruce up your website, and introduce yourself to as many libraries as possible. Bookstores will welcome you, especially when you plan engaging multi-author events. There are opportunities for paperbacks that barely exist for hardcovers, including placement in stores such as Target, Costco, Walmart, and a host of others. Don’t let your paperback launch slip by. For me, as for many, it was when my book broke out.”

The Millions Top Ten: April 2012

We spend plenty of time here on The Millions telling all of you what we’ve been reading, but we are also quite interested in hearing about what you’ve been reading. By looking at our Amazon stats, we can see what books Millions readers have been buying, and we decided it would be fun to use those stats to find out what books have been most popular with our readers in recent months. Below you’ll find our Millions Top Ten list for April.

This

Month

Last

Month

Title

On List

1.

2.

Pulphead

5 months

2.

4.

The Shallows: What the Internet Is Doing to Our Brains

5 months

3.

5.

The Book of Disquiet

5 months

4.

6.

The Gift: Creativity and the Artist in the Modern World

5 months

5.

9.

New American Haggadah

2 months

6.

10.

Train Dreams

3 months

7.

-

The Swerve: How the World Became Modern

1 month

8.

-

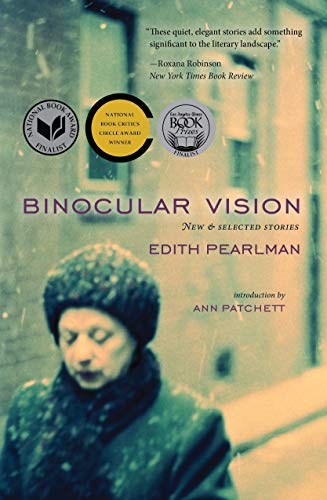

Binocular Vision

1 month

9.

-

Visual Storytelling: Inspiring a New Visual Language

1 month

10.

-

How to Sharpen Pencils

1 month

Last fall, the book world was abuzz with three new novels, the long-awaited books 1Q84 by Haruki Murakami and The Marriage Plot by Jeffrey Eugenides, as well as Chad Harbach's highly touted debut The Art of Fielding. Meanwhile, Millions favorite Helen DeWitt was emerging from a long, frustrating hiatus with Lightning Rods. Now all four are graduating to our Hall of Fame after long runs on our list.

This means we have a new number one: John Jermiah Sullivan's collection of essays Pulphead, which was discussed in glowing terms by our staffer Bill Morris in January. The graduates also open up room for four new books on our list.

A Pulitzer win has propelled Stephen Greenblatt's The Swerve: How the World Became Modern into our Top Ten (fiction finalist Train Dreams by Denis Johnson has already been on our list for a few months). Edith Pearlman's Binocular Vision is another recent award winner making our list for the first time. Don't miss our interview with her from last month.

In January, author Reif Larsen penned an engrossing exploration of the infographic for us. The essay has remained popular, and a book he focused on, Visual Storytelling: Inspiring a New Visual Language, has now landed on our Top Ten. And then in the final spot is David Rees' pencil sharpening manual How to Sharpen Pencils: A Practical and Theoretical Treatise on the Artisanal Craft of Pencil Sharpening. Our funny, probing interview with Rees from last month is a must read.

Near Misses: Leaving the Atocha Station, The Patrick Melrose Novels: Never Mind, Bad News, Some Hope, and Mother's Milk, 11/22/63, The Sense of an Ending, and The Great Frustration. See Also: Last month's list.

The Millions Top Ten: March 2012

We spend plenty of time here on The Millions telling all of you what we’ve been reading, but we are also quite interested in hearing about what you’ve been reading. By looking at our Amazon stats, we can see what books Millions readers have been buying, and we decided it would be fun to use those stats to find out what books have been most popular with our readers in recent months. Below you’ll find our Millions Top Ten list for March.

This

Month

Last

Month

Title

On List

1.

2.

1Q84

6 months

2.

3.

Pulphead

4 months

3.

4.

The Marriage Plot

6 months

4.

6.

The Shallows: What the Internet Is Doing to Our Brains

4 months

5.

7.

The Book of Disquiet

4 months

6.

5.

The Gift: Creativity and the Artist in the Modern World

4 months

7.

8.

The Art of Fielding

6 months

8.

9.

Lightning Rods

6 months

9.

-

New American Haggadah

1 month

10.

10.

Train Dreams

2 months

Ann Patchett's Kindle Single The Getaway Car: A Practical Memoir About Writing and Life has graduated to our Hall of Fame, and Haruki Murakami's 1Q84 slides back into the top spot.

Debuting on our list is Jonathan Safran Foer and Nathan Englander's New American Haggadah, just in time for Passover. We reviewed the new take on an ancient religous text last month. Next month should see a lot of movement on our list as we're likely to see four books graduate to the Hall of Fame, meaning we'll see four new titles debut.

Near Misses: Visual Storytelling: Inspiring a New Visual Language, The Sense of an Ending, Leaving the Atocha Station, The Great Frustration, and The Patrick Melrose Novels: Never Mind, Bad News, Some Hope, and Mother's Milk. See Also: Last month's list.

The Millions Top Ten: February 2012

We spend plenty of time here on The Millions telling all of you what we’ve been reading, but we are also quite interested in hearing about what you’ve been reading. By looking at our Amazon stats, we can see what books Millions readers have been buying, and we decided it would be fun to use those stats to find out what books have been most popular with our readers in recent months. Below you’ll find our Millions Top Ten list for February.

This

Month

Last

Month

Title

On List

1.

2.

The Getaway Car: A Practical Memoir About Writing and Life

6 months

2.

1.

1Q84

5 months

3.

4.

Pulphead

3 months

4.

3.

The Marriage Plot

5 months

5.

8.

The Gift: Creativity and the Artist in the Modern World

3 months

6.

6.

The Shallows: What the Internet Is Doing to Our Brains

3 months

7.

9.

The Book of Disquiet

3 months

8.

5.

The Art of Fielding

5 months

9.

10.

Lightning Rods

5 months

10.

-

Train Dreams

1 month

Ann Patchett's Kindle Single The Getaway Car: A Practical Memoir About Writing and Life lands atop our list, unseating Haruki Murakami's 1Q84, and another Kindle Single, Tom Rachman's short-story ebook The Bathtub Spy, graduates to our Hall of Fame. (Rachman's book The Imperfectionists is already a Hall of Famer.)

Debuting on our list is Denis Johnson's novella Train Dreams, which won mentions from Adam Ross, David Bezmozgis, and Dan Kois in 2011's Year in Reading series.

John Jeremiah Sullivan's Pulphead was a big mover again this month, and Lewis Hyde's The Gift: Creativity and the Artist in the Modern World also jumped a few spots.

Near Misses: The Great Frustration, The Sense of an Ending, Visual Storytelling: Inspiring a New Visual Language, 11/22/63, and The Sisters Brothers. See Also: Last month's list.

Judging Books by Their Covers: U.S. Vs. U.K.

Like we did last year, we thought it might be fun to compare the U.S. and U.K. book cover designs of this year's Morning News Tournament of Books contenders. Book cover design never seems to garner much discussion in the literary world, but, as readers, we are undoubtedly swayed by the little billboard that is the cover of every book we read. Even in the age of the Kindle, we are clicking through the images as we impulsively download this book or that one. I've always found it especially interesting that the U.K. and U.S. covers often differ from one another, suggesting that certain layouts and imagery will better appeal to readers on one side of the Atlantic rather than the other. These differences are especially striking when we look at the covers side by side. The American covers are on the left, and clicking through takes you to a page where you can get a larger image. Your equally inexpert analysis is encouraged in the comments.

The American cover is especially striking, with the bird and skeleton looking like something out of an old illustrated encyclopedia. And the wide black band suggests something important is hidden within. The British version feels generic, with the beach-front watercolor looking like a perhaps slightly more menacing version of the art you'd have hanging in your room at a seaside motel.

The Millions Top Ten: January 2012

We spend plenty of time here on The Millions telling all of you what we’ve been reading, but we are also quite interested in hearing about what you’ve been reading. By looking at our Amazon stats, we can see what books Millions readers have been buying, and we decided it would be fun to use those stats to find out what books have been most popular with our readers in recent months. Below you’ll find our Millions Top Ten list for January.

This

Month

Last

Month

Title

On List

1.

1.

1Q84

4 months

2.

2.

The Getaway Car: A Practical Memoir About Writing and Life

5 months

3.

3.

The Marriage Plot

4 months

4.

6.

Pulphead

2 months

5.

4.

The Art of Fielding

4 months

6.

8.

The Shallows: What the Internet Is Doing to Our Brains

2 months

7.

5.

The Bathtub Spy

6 months

8.

7.

The Gift: Creativity and the Artist in the Modern World

2 months

9.

10.

The Book of Disquiet

2 months

10.

9.

Lightning Rods

4 months

It was a quieter month for our list, with no new titles breaking in and 1Q84 still enthroned at #1. The big movers on the list were John Jeremiah Sullivan's Pulphead, which received a glowing write-up from our staffer Bill, and Nicholas Carr’s The Shallows, which Jonathan Safran Foer called a book that changed his life. With an array of hotly anticipated titles coming in February, we'll see if any newcomers can break in next time around.

Near Misses: Train Dreams, The Sense of an Ending, Leaves of Grass, The Great Frustration, and A Moment in the Sun. See Also: Last month's list.

HBO (Isn’t) Filming The Corrections at My Parents’ House: TV and Fiction

1.

A location scout came through my parents’ neighborhood last month and slid a letter printed on blue paper into each house’s screen door. The letter had HBO’s (fuzzily reproduced and definitely not hi-res) logo at the top and announced in all capital letters that a production team had descended on Mount Vernon, N.Y., in hopes of finding a “HOUSE WITH AN ATTACHED GARAGE.”

It happens that Chez Aronstein has one of those, and my mother found a copy of the letter when she got home from work. She called me in Chicago.

“Look, I won’t keep you,” she said, in a greeting that has become standard for our conversations, “Someone from HBO came to our house. Have you read that book called -- what is it -- ?” I could hear her rustling some papers on the other end, “The Corrections?”

“They want to film the TV series at our house,” she said.

2.

In a short essay written for The New York Times Sunday Book Review last month, Craig Fehrman points out that HBO has recently decided to pay attention to serious fiction -- or what used to be known in the TV industry as “Stuff We Don’t Buy.”

Last year, the premium channel acquired rights to The Corrections for a full four-year series and convinced Jonathan Franzen to write the scripts. Noah Baumbach will direct at least a few episodes. HBO execs also swiped up Jennifer Egan’s 2010 A Visit from the Goon Squad as well as two of 2011’s best-received novels, Karen Russell’s Swamplandia and Chad Harbach’s Art of Fielding. In the case of the latter two, it seems as though the TV rights were negotiated along with publishing rights, so quickly did HBO decide to option them.

Writers have long been squeamish about selling their work to Hollywood directors, let alone to television (not all writers, of course). In his own famously crotchety essay "Why Bother?", Franzen offers the familiar lament that television dumbs down cultural consumption. He argues, “Broadcast TV breaks pleasure into comforting little units—half-innings, twelve-minute acts -- the way my father, when I was very young, would cut my French toast into tiny bites.” To the Franzen of 1996, when compared with television (the Internet wasn’t yet on literature’s radar as an existential threat), the so-called “social” novel simply can’t match up on the issue of popularity. Neither can it win a resource war. “Few serious novelists,” he adds, “can pay for a quick trip to Singapore, or for the mass expert consulting that gives serial TV dramas like E.R. and NYPD Blue their veneer of authenticity.” Viewed as an enemy combatant, television competes directly with novels for eyes, attention, and dollars. Franzen’s essay ends on a hopeful note for books, but the assumption remains that TV and other forms of media will win away the majority of readers. Literature gets the consolation prize of mattering to an important few.

The Franzen of 2011 had a very different perspective when speaking with David Remnick at The New Yorker Festival. Describing his involvement with the HBO series based on his book, he excitedly insisted, “We had an opportunity here -- because it’s not a miniseries, it’s an actual series -- I think to do something that has not been done.” I don’t assume that an individual’s intellectual positions have to remain consistent over a lifetime, but this marks a pretty significant shift -- and one that characterizes what seems to be a growing number of writers. TV no longer stands as the primary enemy of fiction, as long one can write for the right kind of TV. Or: getting a contract with folks like HBO has become the new ideal.

What’s changed?

For one thing, the rise of premium cable has produced practical advantages for authors. Higher production values and an emphasis on multi-year serial dramas allow for financial security, giving them an incentive to stay involved with television projects. Moreover, HBO has demonstrated a willingness to allow novelists to maintain control of their work, offering folks like Franzen (and Egan, who turned down the opportunity) the opportunity to write the scripts. And perhaps most importantly, the popularity of shows like Mad Men, The Wire, and Homeland -- all of which find a place in what Fehrman rightly dubs “post-Sopranos” cable -- enables producers to make compelling cases for slower, unfolding, deliberate narratives. Slower, unfolding, and deliberate narratives comprise the bread and butter of literary fiction. Perhaps television audience tastes have simply come in line with the tastes of readers, while new content-delivery preferences make it possible to exploit the similarity. Tivo and OnDemand everything allow viewers to string together episodes of series on their own schedules -- to cater their media consumption to individual attention spans.

But especially interesting about Franzen’s position with regard to the series is his insistence that TV has allowed him more creative room to explore the themes of The Corrections than did the novel itself. In the same conversation with Remnick, he explains:

Because we had so much more time to work with than there was material in the novel, it was an opportunity to tell a story at many different points in time -- that is spread over thirty years -- and have those all have equal weights […] To figure out how to make that work, it seemed like it could be really cool.

By his account, it turns out that television will present freedom to explore plotlines that the novel limited or foreclosed. For the reigning king of American realist fiction to confess this point -- and to do it readily -- marks a sharp change of direction, suggesting that perhaps we need to start thinking differently about the relationship between television and fiction.

I don’t mean to make hasty qualitative or hierarchical distinctions between TV and novels. It’s easy to say indignantly “Novels are better than TV, you sell-out jerks!” like a petulant writer with exactly zero novels to his credit. (I’m working on it, OKAY?) But I don’t think anyone should begrudge writers like Egan or Franzen for working with HBO. At the very least, Franzen sounds a lot happier than he did 15 years ago, and the fact that The Corrections will reach millions more potential readers on HBO (and on DVD) sounds like an unmitigated win for literary fiction.

Nevertheless, we do need to think about the implications of suggesting that television’s aesthetic capacities can complement, or even supplant, those of novels. For once, we might not have to ask, “Will the novel survive?” Instead, we need to ask what it means that the novel’s future depends on a relationship with TV -- and whether this relationship will be a productive one in the long run.

I started thinking about all of this when it suddenly became possible that The Corrections would be filmed at the house where I grew up.

3.

For young(ish) writers, reading Jonathan Franzen’s The Corrections has for a long time seemed like a kind of prerequisite to engaging in literary practice: writing, reading, thinking about novels and their future or lack of future, or whatever else. When I was in college, the book seemed a kind of talismanic object, a guidebook, a blueprint to follow if I ever wanted to write serious fiction. At the same time, 18-year-old A-J secretly worried that Franzen’s depiction of American middle-class despair and loneliness, and the concurrent self-torture about the shallowness of this despair and loneliness, obviated the need for anything I would ever come up with to describe same. (It’s possible 18-year-old A-J should have been worried about other things, sure, but this is how the story goes).

Regardless, my copy of The Corrections bears the scars of obsessive, borderline psychotic reading: highlights and underlined passages; exclamation points and YESes; check marks and squiggles (most of which have no significance to me now). As an overzealous (and, it can’t be overemphasized, really obnoxious) undergraduate I wrote a chapter of my rambling 120-page thesis (a ponderous object titled “Realistically Speaking: The Politics of the Contemporary Realist Novel”) on Franzen’s work.

I also bought a copy of The Corrections for my father one Christmas and distinctly remember telling the family it was my favorite book. I later found it on a bookcase in our living room, wedged between How to Clean Practically Anything and The Bible for Dummies, its spine un-cracked.

I started giving my mother a précis of this personal literary history, but she cut me off and asked whether she should call HBO. She added that they offered anywhere between $1,000 and $3,000 for every day they were filming. My response was something along the lines of:

“YOU HAVE TO TELL THEM THAT YOU WILL DO WHATEVER IT TAKES TO FILM THIS SHOW IN OUR HOUSE.”

The fact that our house could play a central role in The Corrections validated a long-held suspicion that our Mount Vernon abode -- scene of my childhood -- had something quintessentially American about it. Its “ATTACHED GARAGE,” its magnolia tree and vegetable garden, its slate walk and bay windows could stand in for Franzen’s work. He may have written a book about such a house. But I lived in that house.

[For anyone else keeping score, it’s Aronstein, unpaid freelance essayist and freshman writing teacher, 1 – Franzen, National Book Award-winning author and American literary icon, 0].

I excitedly wondered how HBO would transform my parents’ home into that of the Lamberts, the family at the heart of The Corrections. Some rooms wouldn’t need any modification at all. For example, our garage seemed ready-made for Lambert patriarch Alfred’s metallurgical lab. The production designer wouldn’t have to move anything. The boxes marked “For Yard Sale” and the 1960s-era rocking horse, the Tupperware containers packed with quilts, and the workbench populated with dusty shot glasses all fit almost too perfectly with Franzen’s vision.

Then again, how would this transformation (or lack of transformation) warp my own reading of the book? And more unnervingly, how would the depiction of my childhood home on screen, written into the scripted version of a novel I’ve read at least four times, change the way I remembered and wanted to write about my own experiences? The translation of this particular novel to the screen seemed to have more personal ramifications than those of a general conversation about the relationship between cable and novels. It had to do with my own source material for fiction -- and the potential consequences of seeing what Franzen would do with the scene of my childhood.

And that idea weirded me out.

4.

The formal challenge of novels has always been to represent human experience in a way that attempts to transcend limitations of language: to create something like a shared consciousness among readers of a common text. That this shared consciousness takes place entirely in the realm of thought grants fiction its unique identity, distinguishing it from visual forms of media. What a novel leaves unsaid is often as important as what it does say, and for this reason a piece of fiction’s textual construction of narrative requires a lot of mental work on the part of authors and readers. It has less to do with the scope of a novel’s plot, and more to do with the depth of its inquiry into consciousness.

When we read, we take a mental inventory of the objects and people that inhabit our world and map them onto whatever the author offers us. No matter how meticulously an author creates an environment from words, we still find ourselves spending part of our time with a book trying to match up our own life, possessions, sensations, ideologies, misunderstandings, and relationships with imagined plots, settings, and people. We have to imagine how the sunlight glints through the magnolia tree, how a mother’s voice shouting “MEATLOAF” resonates off of light fixtures, how the wallpaper peels off the walls, how the dog howls at shadows on the ceiling during dinner. Regardless of the size of the screen or the total length of the movie/series/miniseries, visual forms of representation take away this pressure (and pleasure).

That is, in my reading of The Corrections, the Lamberts’ house has always felt and looked like my parents’ house.

What can I say? The brain is sometimes lazy. It conjures approximations of Mr. Darcy, or Daisy Buchanan, or Chip Lambert based on people we know. We try to understand a novel in the vernacular of our own experience. Our relationships condition our mental, emotional, and psychological connection with characters. And when we say that literary fiction is “character-driven,” we mean this: our private interactions with texts depend as much on the associations and imagination of the author as on the associations and imaginations of the reader. Our desire to know them -- and to know them on our own terms -- drives us to read.

Then again, once we see Viggo Mortensen playing Aragorn at Helm’s Deep, it’s difficult to imagine him any other way. Once Rooney Mara walks into the frame as Lisbeth Salander, all we can do is hem and haw about how her interpretation of the character either matches up with or fails to meet expectations that have been molded by books. And I worry that once Ewan McGregor puts on a midwestern accent and a pair of leather pants, I won’t be able to imagine myself as Chip Lambert ever again. Movies and television shows have the uncanny ability to restructure the way that we read novels because they gives us definitive answers about how to see them. When we say that movies fail to live up to expectations created by novels, it’s not just because they don’t comport with our individual imaginings of how the world of a novel is supposed to look. It’s because they rob us of the sense that we have a claim to a private interpretation.

Or more simply: even if I had always imagined our house standing in for the Lamberts’ house, I didn’t want the television to tell me that our house had to be the Lamberts’ house.

What makes novels unique when compared with television has little to do with having enough room to explore certain plotlines in a more detail. What distinguishes them from (even the best, most tasteful, best-acted and directed) television arises from the form of textual engagement itself. Serial dramas on premium cable might in some ways be able to increase the size of the canvas available to fiction writers, and certainly expand the reach of their work. They might demand more mental work than forms like the sitcom. But a novel like The Corrections can seem limitless to readers precisely because it leaves meanings open, leaves parts of characters’ lives only implicitly explored, allows readers to fill in the blanks.

It’s these blanks that I’m worried The Corrections on HBO will fill in.

5.

A representative from HBO came to my parents’ place. After walking around for about 30 minutes, he told them that the house was the right period, but likely too small. To film the scenes properly, they would need a lot more room for the cameras and crew.

It was likely the kind of house that they wanted, but they couldn’t film it effectively.

And, I think, it’s just as well. I’d like to write about that house one day.

Photo courtesy the author.

The Millions Top Ten: December 2011

We spend plenty of time here on The Millions telling all of you what we’ve been reading, but we are also quite interested in hearing about what you’ve been reading. By looking at our Amazon stats, we can see what books Millions readers have been buying, and we decided it would be fun to use those stats to find out what books have been most popular with our readers in recent months. Below you’ll find our Millions Top Ten list for December.

This

Month

Last

Month

Title

On List

1.

1.

1Q84

3 months

2.

3.

The Getaway Car: A Practical Memoir About Writing and Life

4 months

3.

2.

The Marriage Plot

3 months

4.

5.

The Art of Fielding

4 months

5.

4.

The Bathtub Spy

5 months

6.

-

Pulphead

1 month

7.

-

The Gift: Creativity and the Artist in the Modern World

1 month

8.

-

The Shallows: What the Internet Is Doing to Our Brains

1 month

9.

6.

Lightning Rods

4 months

10.

-

The Book of Disquiet

1 month

While the top of our final list for 2011 included the same familiar names and 1Q84 still enthroned at #1, our year-end coverage helped push four eclictic new titles onto the lower half of our list. John Jeremiah Sullivan's Pulphead was one of the most talked about books of 2011 and our own Bill and Garth offered glowing comments on the book in our Year in Reading. Jonathan Safran Foer touted Nicholas Carr’s The Shallows as a book that changed his life. (Our own Emily Mandel also wrote a fascinating essay inspired by the book over a year ago.) Colum McCann said of Fernando Pessoa’s Book of Disquiet, "It was like opening Joyce’s back door and finding another genius there in the garden." Finally, Hannah Gerson came up with "12 Holiday Gifts That Writers Will Actually Use" but only one of them was a book,

The Gift by Lewis Hyde.

With all these new books showing up on our list, four titles got knocked off: Stephen Greenblatt's The Swerve: How the World Became Modern, Julian Barnes' The Sense of an Ending, John Sayles's A Moment in the Sun, and Whitman's Leaves of Grass

Other Near Misses: Train Dreams and The Great Frustration See Also: Last month's list.

A Year in Reading 2011

If you're like me, you keep a list of books you read, and at this time of year, you may run your finger back over it, remembering not just the plots, the soul-lifting favorites, and the drudges cast aside in frustration. You also remember the when and where of each book. This one on a plane to somewhere cold, that one in bed on a warm summer night. That list, even if it is just titles and authors and nothing more, is a diary in layers. Your days, other plots, imaginary people.

And so when, in preparing our annual Year in Reading series, we ask our esteemed guests to tell us about the "best" book(s) they read all year, we do it not just because we want a great book recommendation from someone we admire (we do) and certainly not because we want to cobble together some unwieldy Top 100 of 2011 list (we don't). We do it because we want a peek into that diary. And in the responses we learn how anything from a 300-year-old work to last summer's bestseller reached out and insinuated itself into a life outside those pages.

With this in mind, for an eighth year, we asked some of our favorite writers, thinkers, and readers to look back, reflect, and share. Their charge was to name, from all the books they read this year, the one(s) that meant the most to them, regardless of publication date. Grouped together, these ruminations, cheers, squibs, and essays will be a chronicle of reading and good books from every era. We hope you find in them seeds that will help make your year in reading in 2012 a fruitful one.

As we have in prior years, the names of our 2011 "Year in Reading" contributors will be unveiled one at a time throughout the month as we post their contributions. You can bookmark this post and follow the series from here, or load up the main page for more new Year in Reading posts appearing at the top every day, or you can subscribe to our RSS feed and follow along in your favorite feed reader.

Stephen Dodson, coauthor of Uglier Than a Monkey’s Armpit, proprietor of Languagehat.

Jennifer Egan, author of A Visit from the Goon Squad.

Ben Marcus, author of The Flame Aphabet.

Eleanor Henderson, author of Ten Thousand Saints.

Colum McCann, author of Let the Great World Spin.

Nick Moran, The Millions intern.

Dan Kois, senior editor at Slate.

John Williams, founding editor of The Second Pass.

Michael Bourne, staff writer at The Millions.

Michael Schaub, book critic for NPR.org.

Scott Esposito, coauthor of Lady Chatterley's Brother, proprietor of Conversational Reading.

Hannah Pittard, author of The Fates Will Find Their Way.

Benjamin Hale, author of The Evolution of Bruno Littlemore.

Geoff Dyer, author of Otherwise Known as the Human Condition.

Chad Harbach, author of The Art of Fielding.

Deborah Eisenberg, author of Collected Stories.

Duff McKagan, author of It's So Easy: And Other Lies, former bassist for Guns N' Roses.

Nathan Englander, author of For the Relief of Unbearable Urges.

Amy Waldman, author of The Submission.

Charles Baxter, author of Gryphon: New and Selected Stories.

David Bezmozgis, author of The Free World.

Emma Straub, author of Other People We Married.

Adam Ross, author of Ladies and Gentlemen.

Philip Levine, Poet Laureate of the United States.

Mayim Bialik, actress, author of Beyond the Sling.

Hamilton Leithauser, lead singer of The Walkmen.

Chris Baio, bassist for Vampire Weekend.

Bill Morris, staff writer at The Millions.

Rosecrans Baldwin, author of You Lost Me There.

Carolyn Kellogg, staff writer at the LA Times.

Mark O'Connell, staff writer at The Millions.

Emily M. Keeler, Tumblrer at The Millions, books editor at The New Inquiry.

Edan Lepucki, staff writer at The Millions, author of If You're Not Yet Like Me.

Jami Attenberg, author of The Melting Season.

Dennis Cooper, author of The Marbled Swarm.

Alex Ross, author of Listen to This, New Yorker music critic.

Mona Simpson, author of My Hollywood.

Yaşar Kemal, author of They Burn the Thistles.

Siddhartha Deb, author of The Beautiful and The Damned: A Portrait of the New India.

David Vann, author of Legend of a Suicide.

Jonathan Safran Foer, author of Extremely Loud and Incredibly Close.

Edie Meidav, author of Lola, California.

Ward Farnsworth, author of Farnsworth's Classical English Rhetoric.

Daniel Orozco, author of Orientation and Other Stories.

Hannah Nordhaus, author of The Beekeeper's Lament.

Brad Listi, founder of The Nervous Breakdown.

Alex Shakar, author of Luminarium.

Denise Mina, author of The End of the Wasp Season.

Christopher Boucher, author of How to Keep Your Volkswagen Alive.

Parul Sehgal, books editor at NPR.org.

Patrick Brown, staff writer at The Millions.