Like we did last year, we’re going to have a little fun comparing the U.S. and U.K. book cover designs of this year’s Rooster contenders. Book cover design is a strange exercise in which one attempts to distill iconic imagery from hundreds of pages of text. Engaging the audience is the name of the game here. and it’s interesting to see how the different audiences and sensibilities on either side of the Atlantic can result in very different looks. The American covers are on the left, and clicking through takes you to a larger image. Your equally inexpert analysis is encouraged in the comments.

Judging Books by Their Covers: U.S. Vs. U.K.

The Ghost in My Hands: On Reading Digital Books

The virtual bookshelf on my Kindle is a list of titles that I've read but never held. These books are just ideas, abstractions, nothing less, nothing more.

●

●

●

Forty for 40: A Literary Reader for Lent

The Lenten narrative is marked by violence, suffering, anticipation, and finally, joy. Back by popular demand, here is a literary reader for Lent: 40 stories, poems, essays, and books for the 40 days of this season.

●

●

●

The Physical Book Will Surely Endure: But Will It Endure for the Right Reason?

As an empirical matter, reading on a tablet cannot remotely approach the sensual literary experience offered by an old-fashioned book. The latter is, I’d venture, intrinsically more pleasurable than the former, not unlike the intrinsic difference between high quality toilet paper and the sandpaper stuff used in bus stations.

●

●

●

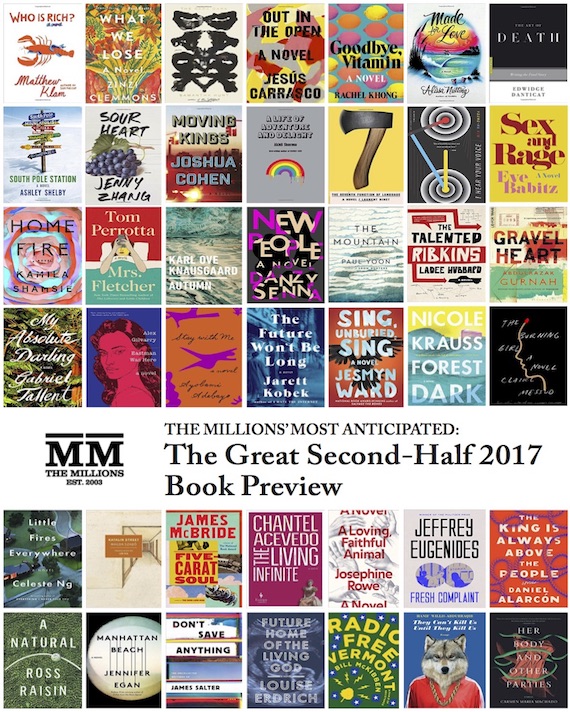

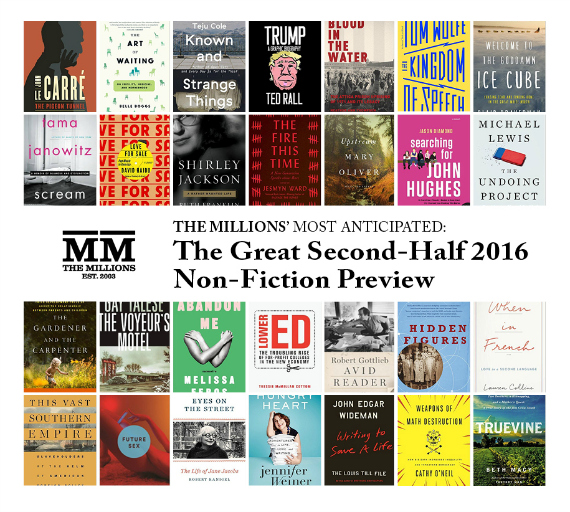

Most Anticipated, Too: The Great Second-Half 2016 Nonfiction Book Preview

Break out the beach umbrellas and the sun block. It’s shaping up to be a very hot summer (and fall!) for new nonfiction.

●

●

●