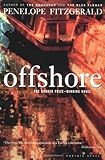

The LA Times called her “The finest British writer alive.”  Julian Barnes called her “the best English novelist of her time.” Penelope Fitzgerald (1916-2000) began publishing at the age of fifty-eight and produced nine novels, three biographies, and a book of short stories by the time she died at eighty-three. Her third novel, Offshore, won the Booker Prize in 1979, while her final novel,The Blue Flower, was named Book of the Year by nineteen British newspapers in 1995 and won the National Book Critics Circle Award in 1997.

Julian Barnes called her “the best English novelist of her time.” Penelope Fitzgerald (1916-2000) began publishing at the age of fifty-eight and produced nine novels, three biographies, and a book of short stories by the time she died at eighty-three. Her third novel, Offshore, won the Booker Prize in 1979, while her final novel,The Blue Flower, was named Book of the Year by nineteen British newspapers in 1995 and won the National Book Critics Circle Award in 1997.

Penelope Fitzgerald’s images enter the reader’s mind with crystalline precision, yet simultaneously, they make you want to re-read what you just read to make sure that what you think happened really happened. Her slim historical novels are the result, one realizes after the fact, of hundreds of hours of research, yet how does she manage to wear her learning so lightly? I first encountered Fitzgerald eleven years ago, thanks to Joan Acocella’s brilliant roundup of her work in The New Yorker. Each novel I read made me want to send the author a fan letter, but I held back, because I felt like I ought to read all of her books before I bothered her. As it happened, she died halfway through my reading jag, and I still regret having been so punctilious.

In the spring of this past year, I curated an eight-author memorial tribute to Penelope Fitzgerald at Manhattan’s KGB Bar. To prepare for the event, I re-read seven of Fitzgerald’s slyly devastating novels. If pressed to name a favorite before re-reading them, I would have said my top three were At Freddie’s, set in an acting school in London in the 1960s, The Beginning of Spring, set in Russia just before the Revolution, and Human Voices, set in the offices of the BBC during World War Two.

In the spring of this past year, I curated an eight-author memorial tribute to Penelope Fitzgerald at Manhattan’s KGB Bar. To prepare for the event, I re-read seven of Fitzgerald’s slyly devastating novels. If pressed to name a favorite before re-reading them, I would have said my top three were At Freddie’s, set in an acting school in London in the 1960s, The Beginning of Spring, set in Russia just before the Revolution, and Human Voices, set in the offices of the BBC during World War Two.

This spring, however, I found myself especially drawn to Fitzgerald’s eighth novel, The Gate of Angels, first published in 1990.

This spring, however, I found myself especially drawn to Fitzgerald’s eighth novel, The Gate of Angels, first published in 1990.

The Gate of Angels is a novel that pits science against religion with the lightest of touches, simply by reminding the reader that there are forces, desire among them, larger than our rational selves, which have the power to overturn all our best-laid plans. In this novel, set in Cambridge, 1912, Fred Fairly, the son of a poor country rector, lives in genteel poverty thanks to a Junior Fellowship at Cambridge, where he resides in the tiny College of Angels. To keep his fellowship, not only does Fred have to lecture in physics, not only does he have to serve as steward, treasurer, librarian, and organist for the College of Angels, he also has to abide by the College’s rules, the most exacting of which requires that he never marry. Of course Fred falls madly in love, and worse, with a girl not of the so-called “marriageable classes.” Daisy Saunders is a working-class girl on the edge of destitution, with whom Fred has little in common except, as we discover, his generosity of spirit, which with typical modesty, Fitzgerald characterizes as an inability on both Fred and Daisy’s part, when asked for help, to say no.

Fred’s troubles are twofold. On the one hand, it’s never clear whether he even has a chance with Daisy at all, until you reread and realize that Daisy can’t love a man until she feels sorry for him. On the other hand, Fitzgerald makes Fred choose between his fellowship at Angels and the girl without whom, in his words, he cannot live. If he marries Daisy, he’ll lose his job and his home. However, as Fitzgerald says, “if Daisy wouldn’t have him, he didn’t see that he would be able to go on at all.” Fred is basically ruining his life by pursuing Daisy, but Fitzgerald crafts a plot in which the reader cannot help but cheer him on.

In an interview with Kerry Fried, Fitzgerald referred to The Gate of Angels as the only novel of hers in which she pulled off a happy ending. Just at the moment when you can let yourself dare to hope that things might work out for Fred and Daisy, Fitzgerald stops, leaving you as breathless as the would-be lovers themselves. Beautiful.

More from A Year in Reading 2011

Don’t miss: A Year in Reading 2010, 2009, 2008, 2007, 2006, 2005

The good stuff: The Millions’ Notable articles

The motherlode: The Millions’ Books and Reviews

Like what you see? Learn about 5 insanely easy ways to Support The Millions, The Millions on Twitter, Facebook, Tumblr.