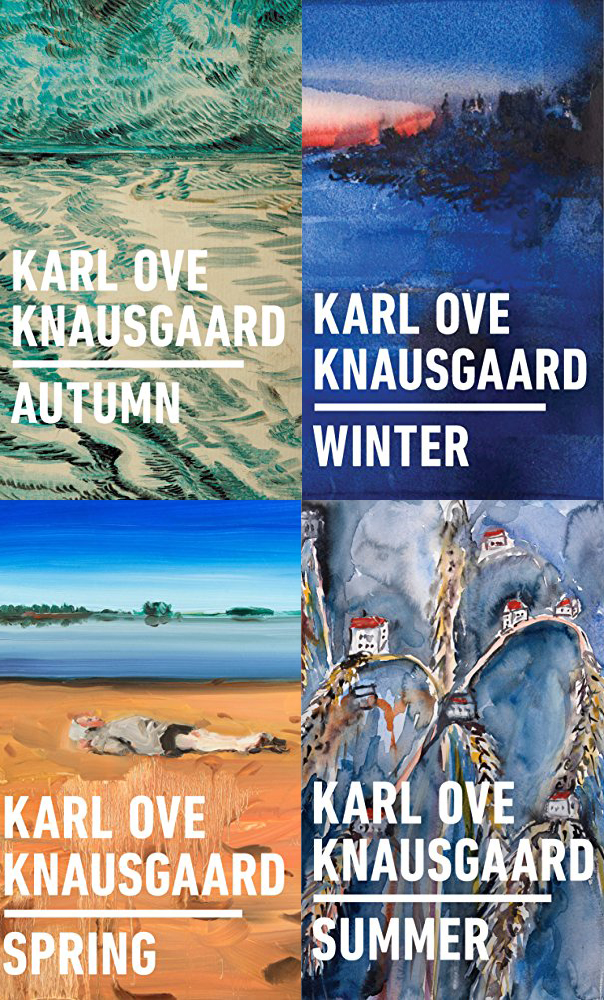

The “seasons quartet” by Karl Ove Knausgaard comprises four books. In order of publication, their titles in English are: Autumn, Winter, Spring, Summer. Made of paper (unless they’re in electronic form), each book resembles a flat rectangular box with three sides open and hinged lids on top and bottom. Inside are sheets of paper, bound with glue and thread to the “closed” side of the box. The cover of the box …

Never mind all that Knausgaardian verbiage. What’s really inside each book? Autumn’s chapters—“September,” “October,” “November”—start with “Letter to an Unborn Child”; short personal essays follow. Winter follows the same scheme, with “Letter to a Newborn Daughter” heading each month. Spring steps out of the group with a novelly structure. Summer falls more or less back in step with essays followed by diary entries, per month.

I was able to read the four books over their publication schedule. Spring I read straight through. Autumn, Winter, and Summer I put down and picked up at leisure. This is the way to do it. A forced march through the essays is not recommended. Even avoiding surfeit by taking them three or four texts at a time, I pondered if these books would have been better, more honest, with the dreck trimmed out, published as a single, longish book.

I was able to read the four books over their publication schedule. Spring I read straight through. Autumn, Winter, and Summer I put down and picked up at leisure. This is the way to do it. A forced march through the essays is not recommended. Even avoiding surfeit by taking them three or four texts at a time, I pondered if these books would have been better, more honest, with the dreck trimmed out, published as a single, longish book.

I didn’t feel that way about Knausgaard’s autofiction opus My Struggle, the first five volumes of which I read twice in a row (the sixth is not yet available), or A Time for Everything, his mind-boggling novel which tells of biblical angels and retells a few Bible stories I’d assumed I knew pretty well.

I didn’t feel that way about Knausgaard’s autofiction opus My Struggle, the first five volumes of which I read twice in a row (the sixth is not yet available), or A Time for Everything, his mind-boggling novel which tells of biblical angels and retells a few Bible stories I’d assumed I knew pretty well.

Those earlier books formed my conviction, shared by many (but not all, for sure), that Karl Ove Knausgaard is one of the greats whose literary works will live. Even given the enthusiasm carried by conviction, though, it’s plain that the seasons quartet would not stand without Knausgaard’s name on them. Leaving aside commercial ploys—banking on the author’s fame to sell a four-book project—should the seasons books have been published as they are, entirely?

Yes, they should have been published as they are, entirely.

The seasons books—and the wonders within—show the process of a literary writer. Sometimes he blathers. Sometimes the writing feels forced; sometimes it’s cutesy. Sometimes … you fall under that old Knausgaard spell, and if you can mark when that happens, you get to see a writer in his “flow.” Through the best and the worst of the seasons quartet, Knausgaard’s well-known quest for authenticity, exercised in My Struggle, is more transparent than ever. Authenticity, or truth, if you will: It’s the quest of every literary writer, from the most cynical to the most idealistic.

The project was conceived as a series of messages to Knausgaard’s then-unborn fourth child. At the beginning of Autumn, he addresses the child directly: “I want to show you our world as it is now: the door, the floor, the water tap and the sink, the garden chair close to the wall beneath the kitchen window, the sun, the water, the trees.”

Clearly, the unborn child is muse, not reader. This disconnect makes the tone disingenuous. In “Chairs” (Winter), the description is made for someone who hasn’t the foggiest idea of what a chair is: “A chair is for sitting on. It consists of four legs on which rests a board.” Of course, by the time the child can read these books, or can read at all, hopefully she’ll have the hang of chairs, doors, floors, etc.

So why describe the chair? (And not even that well, in this case. If you’re so naive to furniture that you need a chair described, and someone says it has four legs, won’t you think of a dog’s or cat’s legs? Four legs and a board to sit on. Picture it and laugh!) Should the editor have persuaded the writer to trim out from the books all the “A chair is for sitting on” bits?

No. Even if the descriptions fail to give us a child’s-eye look at mundane objects, the build-out of tedium can be marvelous. The essay “Winter Sounds” (Winter) starts with the less-than-brilliant observation: “Walking in the forest in winter is quite different from walking there in summer.” And moves to: “The screech of a crow … which in summer is just one note in a greater tapestry of sound, in winter is allowed to fill the air alone, and every single nuance in its rasping, hoarse, seemingly consonant-filled caws stands out: how they rise aggressively at first, then descend mournfully towards the end, leaving behind a sometimes melancholy, sometimes eerie mood among the trees.” Then to a close with snow falling: “That sound, which is no sound, only a nuance of silence, a kind of intensifying or deepening of it, is the sonic expression of winter’s essence.”

The main problem with reading too many of the essays in one sitting is that they can be formulaic. Physical description of an everyday object: “A chair is for sitting on …” Ruminations on the object’s use/activity in everyday life. Digression into deep thoughts. Close with an insightful non sequitur. Bada bing! You almost cringe in anticipation.

At times, the thoughts are trite, better to have been laid to rest in the closed covers of a journal. At times, they can reach right into the heart of life. “A household of family … exists in the real and aspires towards the ideal. All tragedies arise out of this duality, but also all triumphs.”

Then he goes on, “And the feeling of triumph is what prevails in me now, when the kitchen in the house on the other side of the lawn, lit up like a train compartment in the darkness, where only a few hours ago I did the Christmas cleaning, is sparkling clean and bright.”

Should the last bit have been edited out? Wouldn’t the text be more powerful ending with “A household of family,” which beautifully evokes Tolstoy’s opening of Anna Karenina: “Happy families are all alike; every unhappy family is unhappy in its own way”?

Should the last bit have been edited out? Wouldn’t the text be more powerful ending with “A household of family,” which beautifully evokes Tolstoy’s opening of Anna Karenina: “Happy families are all alike; every unhappy family is unhappy in its own way”?

That wouldn’t be Knausgaard. He doesn’t “edit out.” Nor is he beginning a book about a tragic love affair in the glittering courts of imperial Russia. He’s writing about his family and about himself, a man taking a smoke on the lawn of a modest country house in early 21st-century Sweden.

Spring stands apart. It’s a novel—autofiction along the lines of My Struggle—following the time frame of the other seasons books: the period around the birth of the youngest daughter. It’s ripping, heartrending, and like My Struggle, it raises the ethical problem of family-centered memoir and autofiction. On one hand, it’s the author’s and his family’s business. On the other hand, published, it becomes the business of whoever reads it. The exposure the family takes in Spring is daunting.

In Summer, Knausgaard’s diary segues in and out of a fiction whose narrator is an old woman looking back on a disastrous love affair. It’s somewhat in the footsteps of Knausgaard’s college mentor Jon Fosse, though not nearly as perplexing as Fosse’s fiction (at least, what’s available in English). Each time Knausgaard announces the story, within his diary entries, it’s with a similar device: “While so far in this text ‘I’ have represented a forty-seven-year-old Norwegian man residing in Sweden with a wife and four children, ‘I’ will soon, as soon as this sentence ends, represent a seventy-three-year-old woman who is sitting at a writing desk in an apartment in Malmö on a summer evening.”

The old woman’s story never goes far; it’s like an abandoned novel whose ending I didn’t particularly regret missing, though I enjoyed reading what there was of it. The problem was, after the first entry, the transition began to seem gimmicky, a clever device—should the old woman story have been deleted? Or the transitions made in a more conventional, less self-conscious way, by a space in the text, for example? Should the story have been gathered up into one segment, rather than scattered throughout the diary?

No. Leave them in, just as they are. The story and the way it’s told share the writer’s process.

Knausgaard writes most compellingly in the seasons books not of objects like toilets and toothbrushes but of his family’s life. He gazes on the belly of his pregnant wife and sees the child move within “almost like the ripples in water when a sea creature moves just beneath the waves.” He watches his son “curled up in a way I have always been affected by, with one knee pulled up to his belly, his head resting against his arm.” He doesn’t stifle the futile, aching urge to protect his children, nor conceal the shameful urge to judge and disparage them over trifles. He lets out the sheer fun of being with his children, both inside and outside their sphere. He lets us in on the joy of family and the deep fear—the deepest kind there is—that comes with deep love. And then he’ll rattle on about something like coins or kitchen utensils.

The spirit of Knausgaard’s seasons quartet lies in its process and its flaws, its moments of physical loveliness, the hapless insights, emotions joyful and big-hearted, petty and bitter. Like My Struggle, but using a different method, they show us a man (with a more-than-ordinary talent for putting himself in words). You might not identify with him at all, but you feel him. At times you’ll be glad you don’t know him personally. At other times, he’s a given, like a friend you’ve known almost too long: a friend who can irritate the hell out of you, whose messes you more or less forgive, whose gifts win you over time and again.