Mentioned in:

A Year in Reading: 2024

Welcome to the 20th (!) installment of The Millions' annual Year in Reading series, which gathers together some of today's most exciting writers and thinkers to share the books that shaped their year. YIR is not a collection of yearend best-of lists; think of it, perhaps, as an assemblage of annotated bibliographies. We've invited contributors to reflect on the books they read this year—an intentionally vague prompt—and encouraged them to approach the assignment however they choose.

In writing about our reading lives, as YIR contributors are asked to do, we inevitably write about our personal lives, our inner lives. This year, a number of contributors read their way through profound grief and serious illness, through new parenthood and cross-country moves. Some found escape in frothy romances, mooring in works of theology, comfort in ancient epic poetry. More than one turned to the wisdom of Ursula K. Le Guin. Many describe a book finding them just when they needed it.

Interpretations of the assignment were wonderfully varied. One contributor, a music critic, considered the musical analogs to the books she read, while another mapped her reads from this year onto constellations. Most people's reading was guided purely by pleasure, or else a desire to better understand events unfolding in their lives or larger the world. Yet others centered their reading around a certain sense of duty: this year one contributor committed to finishing the six Philip Roth novels he had yet to read, an undertaking that he likens to “eating a six-pack of paper towels.” (Lucky for us, he included in his essay his final ranking of Roth's oeuvre.)

The books that populate these essays range widely, though the most commonly noted title this year was Tony Tulathimutte’s story collection Rejection. The work of newly minted National Book Award winner Percival Everett, particularly his acclaimed novel James, was also widely read and written about. And as the genocide of Palestinians in Gaza enters its second year, many contributors sought out Isabella Hammad’s searing, clear-eyed essay Recognizing the Stranger.

Like so many endeavors in our chronically under-resourced literary community, Year in Reading is a labor of love. The Millions is a one-person editorial operation (with an invaluable assist from SEO maven Dani Fishman), and producing YIR—and witnessing the joy it brings contributors and readers alike—has been the highlight of my tenure as editor. I’m profoundly grateful for the generosity of this year’s contributors, whose names and entries will be revealed below over the next three weeks, concluding on Wednesday, December 18. Be sure to subscribe to The Millions’ free newsletter to get the week’s entries sent straight to your inbox each Friday.

—Sophia Stewart, editor

Becca Rothfeld, author of All Things Are Too Small

Carvell Wallace, author of Another Word for Love

Charlotte Shane, author of An Honest Woman

Brianna Di Monda, writer and editor

Nell Irvin Painter, author of I Just Keep Talking

Carrie Courogen, author of Miss May Does Not Exist

Ayşegül Savaş, author of The Anthropologists

Zachary Issenberg, writer

Tony Tulathimutte, author of Rejection

Ann Powers, author of Traveling: On the Path of Joni Mitchell

Lidia Yuknavitch, author of Reading the Waves

Nicholas Russell, writer and critic

Daniel Saldaña París, author of Planes Flying Over a Monster

Lili Anolik, author of Didion and Babitz

Deborah Ghim, editor

Emily Witt, author of Health and Safety

Nathan Thrall, author of A Day in the Life of Abed Salama

Lena Moses-Schmitt, author of True Mistakes

Jeremy Gordon, author of See Friendship

John Lee Clark, author of Touch the Future

Ellen Wayland-Smith, author of The Science of Last Things

Edwin Frank, publisher and author of Stranger Than Fiction

Sophia Stewart, editor of The Millions

A Year in Reading Archives: 2023, 2022, 2021, 2020, 2019, 2018, 2017, 2016, 2015, 2014, 2013, 2011, 2010, 2009, 2008, 2007, 2006, 2005

The Great Fall 2024 Book Preview

With the arrival of autumn comes a deluge of great books. Here you'll find a sampling of new and forthcoming titles that caught our eye here at The Millions, and that we think might catch yours, too. Some we’ve already perused in galley form; others we’re eager to devour based on their authors, plots, or subject matters. We hope your next fall read is among them.

—Sophia Stewart, editor

October

Season of the Swamp by Yuri Herrera, tr. Lisa Dillman [F]

What it is: An epic, speculative account of the 18 months that Benito Juárez spent in New Orleans in 1853-54, years before he became the first and only Indigenous president of Mexico.

Who it's for: Fans of speculative history; readers who appreciate the magic that swirls around any novel set in New Orleans. —Claire Kirch

The Black Utopians by Aaron Robertson [NF]

What it is: An exploration of Black Americans' pursuit and visions of utopia—both ideological and physical—that spans the Reconstruction era to the present day and combines history, memoir, and reportage.

Who it's for: Fans of Saidiya Hartman's Wayward Lives, Beautiful Experiments and Kristen R. Ghodsee's Everyday Utopia. —Sophia M. Stewart

The Third Realm by Karl Ove Knausgaard, tr. Martin Aitken [F]

What it is: The third installment in Knausgaard's Morning Star series, centered on the appearance of a mysterious new star in the skies above Norway.

Who it's for: Real Knausgaard heads only—The Wolves of Eternity and Morning Star are required reading for this one. —SMS

Brown Women Have Everything by Sayantani Dasgupta [NF]

What it is: Essays on the contradictions and complexities of life as an Indian woman in America, probing everything from hair to family to the joys of travel.

Who it's for: Readers of Durga Chew-Bose, Erika L. Sánchez, and Tajja Isen. —SMS

The Plot Against Native America by Bill Vaughn [F]

What it is: The first narrative history of Native American boarding schools— which aimed "civilize" Indigenous children by violently severing them from their culture— and their enduring, horrifying legacy.

Who it's for: Readers of Ned Blackhawk and Kathleen DuVal. —SMS

The Mighty Red by Louise Erdrich [F]

What it is: Erdrich's latest novel set in North Dakota's Red River Valley is a tale of the intertwined lives of ordinary people striving to survive and even thrive in their rural community, despite environmental upheavals, the 2008 financial crisis, and other obstacles.

Who it's for: Readers of cli-fi; fans of Linda LeGarde Grover and William Faulkner. —CK

The Position of Spoons by Deborah Levy [NF]

What it is: The second book from Levy in as many years, diverging from a recent streak of surrealist fiction with a collection of essays marked by exceptional observance and style.

Who it's for: Close lookers and the perennially curious. —John H. Maher

The Bog Wife by Kay Chronister [F]

What it's about: The Haddesley family has lived on the same West Virginia bog for centuries, making a supernatural bargain with the land—a generational blood sacrifice—in order to do so—until an uncovered secret changes everything.

Who it's for: Readers of Karen Russell and Jeff VanderMeer; anyone who has ever used the phrase "girl moss." —SMS

The Great When by Alan Moore [F]

What it's about: When an 18-year old book reseller comes across a copy of a book that shouldn’t exist, it threatens to upend not just an already post-war-torn London, but reality as we know it.

Who it's for: Anyone looking for a Sherlock Holmes-style mystery dipped in thaumaturgical psychedelia. —Daniella Fishman

The Message by Ta-Nehisi Coates [NF]

What it's about: One of our sharpest critical thinkers on social justice returns to nonfiction, nearly a decade after Between the World and Me, visiting Dakar, to contemplate enslavement and the Middle Passage; Columbia, S.C., as a backdrop for his thoughts on Jim Crow and book bans; and the Israeli-occupied West Bank, where he sees contemporary segregation in the treatment of Palestinians.

Who it’s for: Fans of James Baldwin, George Orwell, and Angela Y. Davis; readers of Nikole Hannah-Jones’s The 1619 Project and Isabel Wilkerson’s Caste, to name just a few engagements with national and racial identity. —Nathalie op de Beeck

Abortion by Jessica Valenti [NF]

What it is: Columnist and memoirist Valenti, who tracks pro-choice advocacy and attacks on the right to choose in her Substack, channels feminist rage into a guide for freedom of choice advocacy.

Who it’s for: Readers of Robin Marty’s The New Handbook for a Post-Roe America, #ShoutYourAbortion proponents, and followers of Jennifer Baumgartner’s [I Had an Abortion] project. —NodB

Gifted by Suzuki Suzumi, tr. Allison Markin Powell [F]

What it's about: A young sex worker in Tokyo's red-light district muses on her life and recounts her abusive mother's final days, in what is Suzuki's first novel to be translated into English.

Who it's for: Readers of Susan Boyt and Mieko Kanai; fans of moody, introspective fiction; anyone with a fraught relationship to their mother. —SMS

Childish Literature by Alejandro Zambra, tr. Megan McDowell [F]

What it is: A wide-ranging collection of stories, essays, and poems that explore childhood, fatherhood, and family.

Who it's for: Fans of dad lit (see: Lucas Mann's Attachments, Keith Gessen's Raising Raffi, Karl Ove Knausgaard's seasons quartet, et al). —SMS

Books Are Made Out of Books ed. Michael Lynn Crews [NF]

What it is: A mining of the archives of the late Cormac McCarthy with a focus on the famously tight-lipped author's literary influences.

Who it's for: Anyone whose commonplace book contains the words "arquebus," "cordillera," or "vinegaroon." —JHM

Slaveroad by John Edgar Wideman [F]

What it is: A blend of memoir, fiction, and history that charts the "slaveroad" that runs through American history, spanning the Atlantic slave trade to the criminal justice system, from the celebrated author of Brothers and Keepers.

Who it's for: Fans of Clint Smith and Ta-Nehisi Coates. —SMS

Linguaphile by Julie Sedivy [NF]

What it's about: Linguist Sedivy reflects on a life spent loving language—its beauty, its mystery, and the essential role it plays in human existence.

Who it's for: Amateur (or professional) linguists; fans of the podcast A Way with Words (me). —SMS

An Image of My Name Enters America by Lucy Ives [NF]

What it is: A collection of interrelated essays that connect moments from Ives's life to larger questions of history, identity, and national fantasy,

Who it's for: Fans of Ives, one of our weirdest and most wondrous living writers—duh; anyone with a passing interest in My Little Pony, Cold War–era musicals, or The Three Body Problem, all of which are mined here for great effect. —SMS

Women's Hotel by Daniel Lavery [F]

What it is: A novel set in 1960s New York City, about the adventures of the residents of a hotel providing housing for young women that is very much evocative of the real-life legendary Barbizon Hotel.

Who it's for: Readers of Mary McCarthy's The Group and Rona Jaffe's The Best of Everything. —CK

The World in Books by Kenneth C. Davis [NF]

What it is: A guide to 52 of the most influential works of nonfiction ever published, spanning works from Plato to Ida B. Wells, bell hooks to Barbara Ehrenreich, and Sun Tzu to Joan Didion.

Who it's for: Lovers of nonfiction looking to cover their canonical bases. —SMS

Blue Light Hours by Bruna Dantas Lobato [F]

What it's about: Through the emanating blue-glow of their computer screens, a mother and daughter, four-thousand miles apart, find solace and loneliness in their nightly Skype chats in this heartstring-pulling debut.

Who it's for: Someone who needs to be reminded to CALL YOUR MOTHER! —DF

Riding Like the Wind by Iris Jamahl Dunkle [NF]

What it is: The biography of Sanora Babb, a contemporary of John Steinbeck's whose field notes and interviews with Dust Bowl migrants Steinbeck relied upon to write The Grapes of Wrath.

Who it's for: Steinbeck fans and haters alike; readers of Kristin Hannah's The Four Winds and the New York Times Overlooked column; anyone interested in learning more about the Dust Bowl migrants who fled to California hoping for a better life. —CK

Innie Shadows by Olivia M. Coetzee [F]

What it is: a work of crime fiction set on the outskirts of Cape Town, where a community marred by violence seeks justice and connection; also the first novel to be translated from Kaaps, a dialect of Afrikaans that was until recently only a spoken language.

Who it's for: fans of sprawling, socioeconomically-attuned crime dramas a la The Wire. —SMS

Dorothy Parker in Hollywood by Gail Crowther [NF]

What it is: A history of the famous wit—and famous New Yorker—in her L.A. era, post–Algonquin Round Table and mid–Red Scare.

Who it's for: Owners of a stack of hopelessly dog-eared Joan Didion paperbacks. —JHM

The Myth of American Idealism by Noam Chomsky and Nathan J. Robinson [NF]

What it is: A potent critique of the ideology behind America's foreign interventions and its status as a global power, and an treatise on how the nation's hubristic pursuit of "spreading democracy" threatens not only the delicate balance of global peace, but the already-declining health of our planet.

Who it's for: Chomskyites; policy wonks and casual critics of American recklessness alike. —DF

Mysticism by Simon Critchley [NF]

What it is: A study of mysticism—defined as an experience, rather than religious practice—by the great British philosopher Critchley, who mines music, poetry, and literature along the way.

Who it's for: Readers of John Gray, Jorge Luis Borges, and Simone Weil. —SMS

Q&A by Adrian Tomine [NF]

What it is: The Japanese American creator of the Optic Nerve comic book series for D&Q, and of many a New Yorker cover, shares his personal history and his creative process in this illustrated unburdening.

Who it’s for: Readers of Tomine’s melancholic, sometimes cringey, and occasionally brutal collections of comics short stories including Summer Blonde, Shortcomings, and Killing and Dying. —NodB

Sonny Boy by Al Pacino [NF]

What it is: Al Pacino's memoir—end of description.

Who it's for: Cinephiles; anyone curious how he's gonna spin fumbling Diane Keaton. —SMS

Seeing Baya by Alice Kaplan [NF]

What it is: The first biography of the enigmatic and largely-forgotten Algerian artist Baya Mahieddine, who first enchanted midcentury Paris as a teenager.

Who it's for: Admirers of Leonora Carrington, Hilma af Klint, Frida Kahlo, and other belatedly-celebrated women painters. —SMS

Absolution by Jeff VanderMeer [F]

What it is: A surprise return to the Area X, the stretch of unforbidding and uncanny coastline in the hit Southern Reach trilogy.

Who it's for: Anyone who's heard this song and got the reference without Googling it. —JHM

The Four Horsemen by Nick Curtola [NF]

What it is: The much-anticipated cookbook from the team behind Brooklyn's hottest restaurant (which also happens to be co-owned by James Murphy of LCD Soundsystem).

Who it's for: Oenophiles; thirty-somethings who live in north Williamsburg (derogatory). —SMS

Seeing Further by Esther Kinsky, tr. Caroline Schmidt [F]

What it's about: An unnamed German woman embarks on the colossal task of reviving a cinema in a small Hungarian village.

Who it's for: Fans of Jenny Erpenbeck; anyone charmed by Cinema Paradiso (not derogatory!). —SMS

Ripcord by Nate Lippens [NF]

What it's about: A novel of class, sex, friendship, and queer intimacy, written in delicious prose and narrated by a gay man adrift in Milwaukee.

Who it's for: Fans of Brontez Purnell, Garth Greenwell, Alexander Chee, and Wayne Koestenbaum. —SMS

The Use of Photography by Annie Ernaux and Marc Marie, tr. Alison L. Strayer [NF]

What it's about: Ernaux's love affair with Marie, a journalist, while she was undergoing treatment for cancer, and their joint project to document their romance.

Who it's for: The Ernaux hive, obviously; readers of Sontag's On Photography and Janet Malcolm's Still Pictures. —SMS

Nora Ephron at the Movies by Ilana Kaplan [NF]

What it is: Kaplan revisits Nora Ephron's cinematic watersheds—Silkwood, Heartburn, When Harry Met Sally, You've Got Mail, and Sleepless in Seattle—in this illustrated book. Have these iconic stories, and Ephron’s humor, weathered more than 40 years?

Who it’s for: Film history buffs who don’t mind a heteronormative HEA; listeners of the Hot and Bothered podcast; your coastal grandma. —NodB

[millions_email]

The Philosophy of Translation by Damion Searls [NF]

What it is: A meditation on the act and art of translation by one of today's most acclaimed practitioners, best known for his translations of Fosse, Proust, et al.

Who it's for: Regular readers of Words Without Borders and Asymptote; professional and amateur literary translators alike. —SMS

Salvage by Dionne Brand

What it is: A penetrating reevaluation of the British literary canon and the tropes once shaped Brand's reading life and sense of self—and Brand’s first major work of nonfiction since her landmark A Map to the Door of No Return.

Who it's for: Readers of Christina Sharpe's Ordinary Notes and Elizabeth Hardwick's Seduction and Betrayal. —SMS

Masquerade by Mike Fu [F]

What it's about: Housesitting for an artist friend in present-day New York, Meadow Liu stumbles on a novel whose author shares his name—the first of many strange, haunting happenings that lead up to the mysterious disappearance of Meadow's friend.

Who it's for: fans of Ed Park and Alexander Chee. —SMS

November

The Beggar Student by Osamu Dazai, tr. Sam Bett [F]

What it is: A novella in the moody vein of Dazai’s acclaimed No Longer Human, following the 30-something “fictional” Dazai into another misadventure spawned from a hubristic spat with a high schooler.

Who it's for: Longtime readers of Dazai, or new fans who discovered the midcentury Japanese novelist via TikTok and the Bungo Stray Dogs anime. —DF

In Thrall by Jane DeLynn [F]

What it is: A landmark lesbian bildungsroman about 16-year-old Lynn's love affair with her English teacher, originally published in 1982.

Who it's for: Fans of Joanna Russ's On Strike Against God and Edmund White's A Boy's Own Story —SMS

Washita Love Child by Douglas Kent Miller [NF]

What it is: The story of Jesse Ed Davis, the Indigenous musician who became on of the most sought after guitarists of the late '60s and '70s, playing alongside B.B. King, Bob Dylan, John Lennon, and more.

Who it's for: readers of music history and/or Indigenous history; fans of Joy Harjo, who wrote the foreword. —SMS

Set My Heart on Fire by Izumi Suzuki, tr. Helen O'Horan [F]

What it is: Gritty, sexy, and wholly rock ’n’ roll, Suzuki’s first novel translated into English (following her story collection, Hit Parade of Tears) follows 20-year-old Izumi navigating life, love, and music in the underground scene in '70s Japan.

Who it's for: Fans of Meiko Kawakami, Ursula K. Le Guin, and Marlowe Granados's Happy Hour. —DF

Didion & Babitz by Lili Anolik [NF]

What it is: A dual portrait of Joan Didion and Eve Babitz, who are so often compared to—and pitted against—each other on the basis of their mutual Los Angeles milieu.

Who it's for: Fans or haters of either writer (the book is fairly pro-Babitz, often at Didion's expense); anyone who has the Lit Hub Didion tote bag. —SMS

The Endless Refrain by David Rowell [NF]

What it's about: How the rise of music streaming, demonitizing of artist revenue, and industry tendency toward nostalgia have laid waste to the musical landscape, and the future of music culture.

Who it's for: Fans of Kyle Chayka, Spence Kornhaber, and Lindsay Zoladz. —SMS

Every Arc Bends Its Radian by Sergio De La Pava [F]

What it is: A mind- and genre-bending detective story set in Cali, Colombia, that blends high-stakes suspense with rigorous philosophy.

Who it's for: Readers of Raymond Chandler, Thomas Pynchon, and Jules Verne. —SMS

Something Close to Nothing by Tom Pyun [F]

What it’s about: At the airport with his white husband Jared, awaiting a flight to Cambodia to meet the surrogate mother carrying their adoptive child-to-be, Korean American Wynn decides parenthood isn't for him, and bad behavior ensues.

Who it’s for: Pyun’s debut is calculated to cut through saccharine depictions of queer parenthood—could pair well with Torrey Peters’s Detransition, Baby. —NodB

Rosenfeld by Maya Kessler [F]

What it is: Kessler's debut—rated R for Rosenfeld—follows one Noa Simmons through the tumultuous and ultimately profound power play that is courting (and having a lot of sex with) the titular older man who soon becomes her boss.

Who it's for: Fans of Sex and the City, Raven Leilani’s Luster, and Coco Mellor’s Cleopatra and Frankenstein. —DF

Lazarus Man by Richard Price [F]

What it is: The former The Wire writer offers yet another astute chronicle of urban life, this time of an ever-changing Harlem.

Who it's for: Fans of Colson Whitehead's Crook Manifesto and Paul Murray's The Bee Sting—and, of course, The Wire. —SMS

Stranger Than Fiction by Edwin Frank [NF]

What it is: An astute curveball of a read on the development and many manifestations of the novel throughout the tumultuous 20th century.

Who it's for: Readers who look at a book's colophon before its title. —JHM

Letters to His Neighbor by Marcel Proust, tr. Lydia Davis

What it is: A collection of Proust’s tormented—and frequently hilarious—letters to his noisy neighbor which, in a diligent translation from Davis, stand the test of time.

Who it's for: Proust lovers; people who live below heavy-steppers. —DF

Context Collapse by Ryan Ruby [NF]

What it is: A self-proclaimed "poem containing a history of poetry," from ancient Greece to the Iowa Workshop, from your favorite literary critic's favorite literary critic.

Who it's for: Anyone who read and admired Ruby's titanic 2022 essay on The Waste Land; lovers of poetry looking for a challenge. —SMS

How Sondheim Can Change Your Life by Richard Schoch [NF]

What it's about: Drama professor Schoch's tribute to Stephen Sondheim and the life lessons to be gleaned from his music.

Who it's for: Sondheim heads, former theater kids, end of list. —SMS

The Serviceberry by Robin Wall Kimmerer [NF]

What it is: 2022 MacArthur fellow and botanist Kimmerer, an enrolled member of the Citizen Potawatomi Nation, (re)introduces audiences to a flowering, fruiting native plant beloved of foragers and gardeners.

Who it’s for: The restoration ecologist in your life, along with anyone who loved Braiding Sweetgrass and needs a nature-themed holiday gift. —NodB

My Heart Belongs in an Empty Big Mac Container Buried Beneath the Ocean Floor by Homeless [F]

What it is: A pseudonymous, tenderly comic novel of blue whales and Golden Arches, mental illness and recovery.

Who it's for: Anyone who finds Thomas Pynchon a bit too staid. —JHM

Yoke and Feather by Jessie van Eerden [NF]

What it's about: Van Eerden's braided essays explore the "everyday sacred" to tease out connections between ancient myth and contemporary life.

Who it's for: Readers of Courtney Zoffness's Spilt Milk and Jeanna Kadlec's Heretic. —SMS

Camp Jeff by Tova Reich [F]

What it's about: A "reeducation" center for sex pests in the Catskills, founded by one Jeffery Epstein (no, not that one), where the dual phenomena of #MeToo and therapyspeak collide.

Who it's for: Fans of Philip Roth and Nathan Englander; cancel culture skeptics. —SMS

Selected Amazon Reviews by Kevin Killian [NF]

What it is: A collection of 16 years of Killian’s funniest, wittiest, and most poetic Amazon reviews, the sheer number of which helped him earn the rarefied “Top 100” and “Hall of Fame” status on the site.

Who it's for: Fans of Wayne Koestenbaum and Dodie Bellamy, who wrote introduction and afterword, respectively; people who actually leave Amazon reviews. —DF

Cher by Cher [NF]

What it is: The first in a two-volume memoir, telling the story of Cher's early life and ascendent career as only she can tell it.

Who it's for: Anyone looking to fill the My Name Is Barbra–sized hole in their heart, or looking for something to tide them over until the Liza memoir drops. —SMS

The City and Its Uncertain Walls by Haruki Murakami, tr. Philip Gabriel [F]

What it is: Murakami’s first novel in over six years returns to the high-walled city from his 1985 story "Hard-Boiled Wonderland and the End of the World" with one man's search for his lost love—and, simultaneously, an ode to libraries and literature itself.

Who it's for: Murakami fans who have long awaited his return to fiction. —DF

American Bulk by Emily Mester [NF]

What it's about: Reflecting on what it means to "live life to the fullest," Mester explores the cultural and personal impacts of America’s culture of overconsumption, from Costco hauls to hoarding to diet culture—oh my!

Who it's for: Lovers of sustainability; haters of excess; skeptics of the title essay of Becca Rothfeld's All Things Are Too Small. —DF

The Icon and the Idealist by Stephanie Gorton [NF]

What it is: A compelling look at the rivalry between Margaret Sanger, of Planned Parenthood fame, and Mary Ware Dennett, who each held radically different visions for the future of birth control.

Who it's for: Readers of Amy Sohn's The Man Who Hated Women and Katherine Turk's The Women of NOW; anyone interested in the history of reproductive rights. —SMS

December

Rental House by Weike Wang [F]

What it's about: Married college sweethearts invite their drastically different families on a Cape Code vacation, raising questions about marriage, intimacy, and kinship.

Who it's for: Fans of Wang's trademark wit and sly humor (see: Joan Is Okay and Chemistry); anyone with an in-law problem.

Woo Woo by Ella Baxter [F]

What it's about: A neurotic conceptual artist loses her shit in the months leading up to an exhibition that she hopes will be her big breakout, poking fun at the tropes of the "art monster" and the "woman of the verge" in one fell, stylish swoop.

Who it's for: Readers of Sheena Patel's I'm a Fan and Chris Kraus's I Love Dick; any woman who is grateful to but now also sort of begrudges Jenny Offil for introducing "art monster" into the lexicon (me). —SMS

Berlin Atomized by Julia Kornberg, tr. Jack Rockwell and Julia Kornberg [F]

What it's about: Spanning 2001 to 2034, three Jewish and downwardly mobile siblings come of age in various corners of the world against the backdrop of global crisis.

Who it's for: Fans of Catherine Lacey's Biography of X and Joshua Cohen's The Netanyahus. —SMS

Sand-Catcher by Omar Khalifah, tr. Barbara Romaine [F]

What it is: A suspenseful, dark satire of memory and nation, in which four young Palestinian journalists at a Jordanian newspaper are assigned to interview an elderly witness to the Nakba, the violent 1948 expulsion of native Palestinians from Israel—but to their surprise, the survivor doesn’t want to rehash his trauma for the media.

Who it’s for: Anyone looking insight—tinged with grim humor—into the years leading up to the present political crisis in the Middle East and the decades-long goal of Palestinian autonomy. —NodB

The Shutouts by Gabrielle Korn [F]

What it's about: In the dystopian future, mysteriously connected women fight to survive on the margins of society amid worsening climate collapse.

Who it's for: Fans of Korn's Yours for the Taking, which takes place in the same universe; readers of Becky Chambers and queer-inflected sci-fi. —SMS

What in Me Is Dark by Orlando Reade [NF]

What it's about: The enduring, evolving influence of Milton's Paradise Lost on political history—and particularly on the work of 12 revolutionary readers, including Malcom X and Hannah Arendt.

Who it's for: English majors and fans of Ryan Ruby and Sarah Bakewell—but I repeat myself. —SMS

The Afterlife Is Letting Go by Brandon Shimoda [NF]

What it's about: Shimoda researches the mass incarceration of Japanese Americans during WWII, and speaks with descendants of those imprisoned, for this essay collection about the “afterlife” of cruelty and xenophobia in the U.S.

Who it’s for: Anyone to ever visit a monument, museum, or designated site of hallowed ground where traumatic events have taken place. —NodB

No Place to Bury the Dead by Karina Sainz Borgo, tr. Elizabeth Bryer [F]

What it's about: When Angustias Romero loses both her children while fleeing a mysterious disease in her unnamed Latin American country, she finds herself in a surreal, purgatorial borderland where she's soon caught in a power struggle.

Who it's for: Fans of Maríana Enriquez and Mohsin Hamid. —SMS

The Rest Is Silence by Augusto Monterroso, tr. Aaron Kerner [F]

What it is: The author of some of the shortest, and tightest, stories in Latin American literature goes long with a metafictional skewering of literary criticism in his only novel.

Who it's for: Anyone who prefers the term "palm-of-the-hand stories" to "flash fiction." —JHM

Tali Girls by Siamak Herawi, tr. Sara Khalili [F]

What it is: An intimate, harrowing, and vital look at the lives of girls and women in an Afghan mountain village under Taliban rule, based on true stories.

Who it's for: Readers of Nadia Hashimi, Akwaeke Emezi, and Maria Stepanova. —SMS

Sun City by Tove Jansson, tr. Thomas Teal [F]

What it's about: During her travels through the U.S. in the 1970s, Jansson became interested in the retirement home as a peculiarly American institution—here, she imagines the tightly knit community within one of them.

Who it's for: Fans of Jansson's other fiction for adults, much of which explores the lives of elderly folks; anyone who watched that documentary about The Villages in Florida. —SMS

Editor's note: We're always looking to make our seasonal book previews more useful to the readers, writers, and critics they're meant to serve. Got an idea for how we can improve our coverage? Tell me about it at sophia@themillions.com.

[millions_email]

Valeria Luiselli on Writing Through the Pandemic

After her latest novel, Lost Children Archive, won the British Rathbone Folio Prize, Valeria Luiselli spoke to Claudia Torrens at AP News about the importance of artists continuing to write during this uncertain time. “I think it is my duty, and the duty of every writer," she says, "whether is a science-fiction writer, a journalist, a poet, each at their own pace and within their own capacities, to document this moment."

A Year in Reading: Tanaïs

This year, I sought literature that reverberated with tenderness and rage. Reading afforded me much-needed quietude and pockets of silence in these increasingly fascist times, amidst a relentless, raucous political commentary that we can’t afford to turn off. We can’t afford ignorance, but we do still need spaces to dream, to reimagine the world, to counter erasures of stories we deserve and need to know, the ones omitted from the dominant culture’s record. As writers, we write ourselves and the stories we never saw ourselves in, the stories that are the most terrifying to tell. I craved intimate work that took me to subterranean, secret, otherworldly, historic, ancient, and syncretic corners of literature, where borders and identities dissolved into hybrid forms. I wanted to read work that made me feel connected to my body, my senses, and collective memories.

I Lalla, the utterances of 14th-century Kashmiri mystic poet Lal Ded, translated by poet and translator Ranjit Hoskote, were a portal into another time, when a rebellious woman renounced her family duties to become a devotee—and yet, I read this work in the context of the present-day political turmoil not only in India-occupied Kashmir but throughout India, where student protestors are being violently beaten and tear gassed by the police because of their opposition to the Citizenship Amendment Bill, which will allow the Indian government to send people without paperwork to detention camps. Reading Lal Ded today, each line is as much a wound as it is a balm.

I revisited iconic feminist works that have never felt more prescient, including Borderlands/La Frontera: The New Mestiza by Gloria Anzaldúa, which interrogates the U.S.-Mexico border: the history of white supremacist imperialism and indigenous genocide, feminist theory, and femme divine mythologies. Valeria Luiselli’s Lost Children Archive documented the heartbreaking dissolution of a family on a road trip across these desert borderlands, and I ached the entire book through, holding its heart—the children savagely separated from their parents at the border—close to my own. Another spectacular novel set in the desert, The Other Americans by Laila Lalami, masterfully weaves a polyphonic tapestry of narrators sharply divided by race, religion, class, desire, and aspirations, unfurling the story of a Moroccan immigrant killed in a hit-and-run. Imagining a Muslim family’s tragedy in the Mojave Desert felt like a necessary complement—one that I’ve never read before—to the post-9/11 literature set in New York City. Lalami’s structure summoned another masterful work of art, Kurosawa’s Rashomon. I loved how both of these novels draw the desertscape, in all of its solitude and endlessness and metaphors. Desertscape forms over millions of years, a steady denuding of the earth into monochromatic wasteland, where everything is wildly alive, but camouflaged, in plain sight.

Saidiya Hartman’s Wayward Lives, Beautiful Experiments opened a radical door of perception into early 20th-century black women’s intimacy as revolution, how their love and queerness and kinship was the heart of their survivorship against societal and state violence. Femme in Public, a poetry collection by ALOK, a nonbinary transfemme poet, performance artist, educator, and cultural theorist, probes the urgent question that I find myself wondering every time I show up to the page: What feminine part of yourself did you have to destroy in order to survive in this world? Each poem is a dart of truth puncturing the systemic, colonial violence of the gender binary, one of the first ways we learn to erase ourselves.

After Toni Morrison’s passing, I read her collected essays and speeches, The Source of Self-Regard, each night before bed, unmoored by the breadth and brilliance of her mind. Her nonfiction is a clarion light that has never felt more eternal, and it made me want to read her fictive masterpiece Beloved, for which I made a perfume (for an event in her honor) composed of notes in the book: sweet grass, salt water, rose, and blood cedar. There is no other writer who threads the olfactory with such elegant and devastating precision. Similarly, Arundhati Roy’s collected nonfiction My Seditious Heart reignited my blaze for her intellectual fire and activism and infinitely readable voice—and the collection illuminates her decades-long commitment to freedom and social justice. This work is a nonfictional journey between her two great works of fiction, The God of Small Things and The Ministry of Utmost Happiness.

Carmen Maria Machado’s memoir In the Dream House is a heart-wrenching, hybrid work that moved me to my core as a survivor. Over the years, I’ve learned that there is no greater feeling of solidarity than being able to bear witness to another survivor’s experience, and in the wake of so many public reckonings with abusers, to read a work that goes inward so inventively was a total wonder. When I think of how I learned to read and write, healing or holding space for trauma were not a part of the writer’s project, but the old rules don’t seem to matter as much to me anymore, we cannot afford to hold our tongues. Fariha Róisìn’s poetry collection How to Cure a Ghost bares and bears everything, and it felt like I’d found a book waiting for me my whole life, a way of seeing that reflects the world as I’ve lived in it, as a Bangladeshi, brown, bodied, Muslim femme person.

Poetry and essay are both forms that Hanif Abdurraquib renders with such elegant melancholy and beautiful rhythm, and I loved his poetry collection A Fortune for Your Disaster, as well as his essay series on the Paris Review, Notes on Pop, about songs and memory. My last book for the year will be published in 2020, My Baby First Birthday, a poetry collection by Jenny Zhang. It’s a radiant and resolute work that had me questioning everything, like what life means when you didn’t ask to be born; how we must translate ourselves for whiteness and patriarchy through our trauma, which can feel like selling ourselves out when we are never replenished by a system that asks us to sacrifice so much. And yet, these poems are a soothsaying for the future we want to live in, where we understand the innate beauty of our planet, of ourselves, our friendships, where we forgive our own transgressions, remembering to stay tilted towards the light.

A Year in Reading: Ayşe Papatya Bucak

I am vulnerable to the word

once.

“‘Once long ago,’ Rogni said, ‘an old woman in a flowered housedress sat on a kitchen chair steeping tea in a cracked brown teapot. She was the Nurse-of-Becoming; she was getting ready to imagine two sisters. Only she made three mistakes.'” So begins Kathryn Davis’s Labrador. The curtain parts. The world disappears.

One of my favorite things to read this year has been Sabrina Orah Mark’s series Happily, on fairy tales and motherhood, online at The Paris Review. “My son’s first grade teacher pulls me aside to tell me she’s concerned about Noah and the Ghost People,” the first essay begins. The curtain parts. The world divides. The ghost people appear by my side.

“In the house opposite, in the dark night of the garden, the governesses are playing cards. Eléonore who seems so straitlaced is laughing like a madwoman,” writes Anne Serre (and translator Mark Hutchinson), in The Governesses, another of my favorites. One that the New Directions catalog copy refers to as a “semi-deranged erotic fairy tale,” by the way. The curtains part. A light comes on the dark.

“Mouths open to the sun, they sleep,” begins Valeria Luiselli’s novel Lost Children Archive, yet another favorite. The curtain parts. The dream begins. Current events become story.

Each year I tell my creative writing classes they must attempt to write literature, and literature does not let readers escape the world, it forces them to engage with the world. Your writing can be in any genre, I tell them, but its goal must be engagement, not escape. There are lots of enjoyable books that serve as an escape, I say. But that’s not what we’re writing.

I am not so sure anymore though.

Don’t I use literature as an escape?

Once I asked a student what he

thought made a good book.

“A book that changes how you

think?” he said.

“Then what makes a great book?”

I asked.

“A book that changes how you

act?” he said.

Do books ever change how I act?

I wonder.

I tell my students that writing

should give the reader an experience.

That implies books could change

how we act. Experiences change how we act. Don’t they? Shouldn’t they?

In the spring, I was supposed to review Kathryn Davis’s novel The Silk Road. I volunteered to do it. I love the strange worlds of Kathryn Davis’s creations, and a novel that shifted between the Philadelphia suburbs of my mother’s ancestors and the silk road journeys of my father’s ancestors seemed custom-built for me. But I read it and I faltered. I didn’t understand it. I wasn’t sure if I liked it. So I read it again, and I liked it more, but understood it less. Possibly I became obsessed with it and the strange siblings that drift across its pages in some kind of maybe physical, maybe metaphysical journey after one of them has died. Possibly I read it three times. Still I couldn’t review it.

I suggested to the editor that I write an essay on Davis’s work as a whole instead. They agreed. So I reread Duplex, my favorite (schoolteacher dates sorcerer in suburban town studied by robots) and Hell, my second favorite (braided narrative of households across time and space, but much stranger than that makes it sound). I read Versailles (an often humorous Marie Antoinette retelling), The Walking Tour (two couples take a tour of Wales, not everybody comes home) and finally Labrador (awkward sister gets taken to Arctic by eccentric grandfather who is eaten by polar bear while graceful sister stays home and gets pregnant).

It was one of my favorite and strangest periods of reading. Dream upon dream. Not daydreams, which are carefully constructed fantasies, but night dreams, made up of recognizable parts assembled in peculiar configurations. I went into each novel and came back out again unable to recount exactly where I’d been. (The Silk Road aptly begins: “We were in the labyrinth.”) Maybe this doesn’t sound like a positive recommendation; but what I am trying to say is I lived inside of Kathryn Davis’s writing for awhile, and if you are the kind of person who wants to see the world with greater wonder, who is always looking for foreign lands in the backs of wardrobes, who understands death to be close all of the time but also probably not within the realm of imagining—these books are for you. They are an escape, though one from which you return with a greater capacity for seeing and appreciating the wondrous world.

But still I didn’t write the

essay.

Maybe this had less to do with

the difficulties of writing and more to do with the difficulties of life.

My father died this year. Now I have another father, of memory and story and imagination, an autofictional father existing in another dimension. Now I tell stories about him that he will never hear. On his death certificate, the funeral home listed him as female. They also handed his box of remains to my mother inside of a sparkly green gift bag. Upon receiving this gift, my mother and I did not react, nor look at each other, until we stepped outside of the building and burst into laughter. “It’s okay, I’ll reuse it,” my mother said. We laughed even harder. But my father, who appreciated jokes, perhaps would not have appreciated this one.

“Will you weep when I die?” he

used to ask me, as if there was any doubt.

Once once once. I had a father.

Escape engage. Escape engage.

The story of mourning.

In Turkish there is a storytelling tense, not past, not present, not future. The tense for repeating things you heard secondhand but did not have direct experience of. The once-upon-a-time tense. In that tense I still have a father.

When my father died he had both

Alzheimer’s and a rare form of mouth cancer. Because of the Alzheimer’s he

sometimes forgot he had cancer. My mother would have to tell him again. And again.

If she could have, my mother

would have let him forget. But my father would moan, or scream, or really

scream, that his mouth hurt, why wasn’t she taking him to the dentist, why

wasn’t she helping him. Even after weeks of chemo, he could still forget.

Wouldn’t it be nice if

forgetting was an escape? But all it did was make his pain inexplicable.

Because I am both Turkish and not, every year I read as many Turkish writers as I can. This year I had much appreciation for: Ayşegül Savaş’s lyric novel Walking on the Ceiling; jailed politician Selahattin Demirtaş’s sometimes charming, sometimes brutal story collection Dawn; Ece Temelkuran’s dire but believable warning that engagement without activism becomes the mere “expression and exchange of emotional responses” How to Lose a Country: The 7 Steps from Democracy to Dictatorship; Can Dündar’s surprisingly humorous and even joyful We Are Arrested: A Journalist’s Notes From a Turkish Prison; and journalist Ahmet Altan’s more somber I Will Never See the World Again (translated by Yasemin Congar), also written in jail and smuggled out via his lawyers.

But the book that stopped me in my tracks was More by Hakan Günday (translated by Zeynep Beler). You can’t find a summary or review of the novel that doesn’t include words like harrowing, disturbing, and unsettling. The narrator is a teenager engaged in the family business—smuggling refugees for money with zero concern for the refugees’ safety or survival. It is no surprise that this novel has not had the popularity of its much sunnier bookend, Mohsin Hamid’s Exit West. Where Hamid uses fantasy to create hope, Günday uses it to create horror. The title comes from the refugees’ cries for “more” food as the narrator scrapes excrement off the floor of the concrete bunker they are buried in during the smuggling process. The novel, which to be clear, I admired tremendously, reads very much like a nightmare—appropriately so given the real life circumstances it is trying to place the reader inside of. But even it, was also, for me, an escape. What have I done for the Syrian refugees other than imagine their nightmare? Doesn’t educating myself about the horrors of the world make me feel proud! But what does it do for those who suffer them?

I guess I believe reading

generates empathy. I feel pretty sure it can offer readers life experiences

they would not otherwise have. But does it change how we act?

Engage escape engage

escape.

When I read Ahmet Altan, I am outraged at his imprisonment. When I read the news of his release, I feel joy. When I read the news of his re-arrest, I feel outrage again. But feelings aren’t engagement, are they?

Are they?

For me, the action that reading triggers is writing. And here is my bigger fear: that writing isn’t engagement either.

I don’t doubt the value of

literature, of representation, of the framing of narratives, of making our pain

explicable, but writing isn’t enough. How could it be? And yet, at times, I

have treated it as if it is. Even now, even now as I type this and imagine you

reading it, I am hoping that you, not I, will be moved to act, to right the

world, right…now.

More from A Year in Reading 2019

Do you love Year in Reading and the amazing books and arts content that The Millions produces year round? We are asking readers for support to ensure that The Millions can stay vibrant for years to come. Please click here to learn about several simple ways you can support The Millions now.

Don't miss: A Year in Reading 2018, 2017, 2016, 2015, 2014, 2013, 2012, 2011, 2010, 2009, 2008, 2007, 2006, 2005

[millions_ad]

Man Booker Prize Names 2019 Longlist

The Man Booker Prize, which "aims to promote the finest in fiction by rewarding the best novel of the year written in English and published in the United Kingdom," announced its 2019 longlist.

Whittled down from 151 novels published in the U.K. or Ireland between Oct. 1, 2018 and Sept. 30, 2019, the 13-title longlist includes two previous winners (Salman Rushdie and Margaret Atwood), one American author (Lucy Ellmann), and one debut novelist (Oyinkan Braithwaite). We are also extremely excited that our own contributing editor Chigozie Obioma made the list!

Here's the 2019 "Booker Dozen," featuring 13 novels—plus applicable bonus links:

The Testaments by Margaret Atwood (Read our 2015 interview with Atwood)

Night Boat to Tangier by Kevin Barry (Read Barry's 2017 Year in Reading entry)

My Sister, The Serial Killer by Oyinkan Braithwaite (Featured in our November Most Anticipated List)

Ducks, Newburyport by Lucy Ellmann

Girl, Woman, Other by Bernardine Evaristo

The Wall by John Lanchester

The Man Who Saw Everything by Deborah Levy (Featured in our Great Second-Half Book Preview)

Lost Children Archive by Valeria Luiselli (Read reviews of Luiselli's other works here and here)

An Orchestra of Minorities by Chigozie Obioma (Our interview with Obioma)

Lanny by Max Porter (Read our review of Lanny)

Quichotte by Salman Rushdie

10 Minutes 38 Seconds in This Strange World by Elif Shafak

Frankissstein by Jeanette Winterson

The Man Booker Prize shortlist will be announced on Sept. 3rd.

[millions_ad]

Women’s Prize for Fiction Names 2019 Longlist

Previously known as the Bailey’s Prize for Fiction (2013-2016) and the Orange Prize for Fiction (1996-2012), the Women's Prize for Fiction announced its 2019 shortlist today. The award, created in the wake of a 1991 all-male Booker Prize shortlist, celebrates “excellence, originality and accessibility in women’s writing from throughout the world.” The longlist, which includes seven debut novels, is as follows (with bonus links when possible):The Silence of the Girls by Pat Barker (also nominated for the 2018 Costa Book Awards shortlist and featured in our September Preview)Remembered by Yvonne Battle-FeltonMy Sister, the Serial Killer by Oyinkan Braithwaite (featured in our November Preview) The Pisces by Melissa Broder (mentioned in Marta Bausell's 2018 Year in Reading and interviewed by The Millions here)Milkman by Anna Burns (winner of the 2018 Man Booker Prize)Freshwater by Akwaeke Emezi (mentioned in not one, or even two, but three Year in Reading posts; Emezi was also a 5 Under 35 honoree this year)Ordinary People by Diana Evans (featured in our September Preview)Swan Song by Kelleigh Greenberg-JephcottAn American Marriage by Tayari Jones (February Preview)Number One Chinese Restaurant by Lillian Li (interview with Li here, plus mentions in quite a few of our Year in Reading posts) Bottled Goods by Sophie van LlewynLost Children Archive by Valeria Luiselli (featured in two Previews and two Year in Reading posts)Praise Song for the Butterflies by Bernice L. McFadden (praised in Margaret Wilkerson Sexton's Year in Reading)Circe by Madeline Miller (Steph Opitz's , Marta Bausells's, and Kaulie Lewis's Year in Reading)Ghost Wall by Sarah Moss (reviewed here and here)Normal People by Sally Rooney (in two 2018 Year in Reading posts)The shortlist will be announced on April 29th, and the winner will be selected on June 5th.

Tuesday New Release Day: Starring Luiselli, Morrison, Williams, Newman, and More

Here’s a quick look at some notable books—new titles from the likes of Valeria Luiselli, Toni Morrison, John Williams, Sandra Newman and more—that are publishing this week.

Want to learn more about upcoming titles? Then go read our most recent book preview. Want to help The Millions keep churning out great books coverage? Then sign up to be a member today.

American Spy by Lauren Wilkinson

Here's what Publishers Weekly had to say about American Spy: "Wilkinson’s unflinching, incendiary debut combines the espionage novels of John le Carré with the racial complexity of Ralph Ellison’s Invisible Man. Marie Mitchell, the daughter of a Harlem-born cop and a Martinican mother, is an operative with the FBI in the mid-’80s peak of the Cold War. Marie is languishing in the bureaucratic doldrums of the agency, a black woman stultified by institutional prejudice relegated to running snitches associated with Pan-African movements with Communist links. All this changes when she is tapped by the CIA to insinuate herself with Thomas Sankara, the charismatic new leader of Burkina Faso, in a concerted effort to destabilize his fledgling government and sway them toward U.S. interests. Now the key player in a honeypot scheme to entrap Sankara, Marie finds herself questioning her loyalties as she edges closer to both Sankara and the insidious intentions of her handlers abroad. In the bargain, she also hopes to learn the circumstances surrounding the mysterious death of her elder sister, Helene, whose tragically short career in the intelligence community preceded Marie’s own. Written as a confession addressed to her twin sons following an assassination attempt on her life, the novel is a thrilling, razor-sharp examination of race, nationalism, and U.S. foreign policy that is certain to make Wilkinson’s name as one of the most engaging and perceptive young writers working today. Marie is a brilliant narrator who is forthright, direct, and impervious to deception—traits that endow the story with an honesty that is as refreshing as it is revelatory. This urgent and adventurous novel will delight fans of literary fiction and spy novels alike."

Lost Children Archive by Valeria Luiselli

Here's what Publishers Weekly had to say about Lost Children Archive: "Luiselli’s powerful, eloquent novel begins with a family embarking on a road trip and culminates in an indictment of America’s immigration system. An unnamed husband and wife drive, with their children in the backseat, from New York City to Arizona, he seeking to record remnants of Geronimo and the Chiricahua Apache, she hoping to locate two Mexican girls last seen awaiting deportation at a detention center. The husband recounts for the 10-year-old son and five-year-old daughter stories about a legendary band of Apache children. The wife explains how immigrant children become separated from parents, losing their way and sometimes their lives. Husband, wife, son, and daughter nickname themselves Cochise, Lucky Arrow, Swift Feather, and Memphis, respectively. When Swift Feather and Memphis go off alone, they become lost, then separated, then intermingled with the Apache and immigrant children, both imagined and all too real. As their parents frantically search, Memphis trades Swift Feather’s map, compass, flashlight, binoculars, and Swiss Army knife for a bow and arrow, leaving them with only their father’s stories about the area to guide them. Juxtaposing rich poetic prose with direct storytelling and brutal reality and alternating narratives with photos, documents, poems, maps, and music, Luiselli explores what holds a family and society together and what pulls them apart. Echoing themes from previous works (such as Tell Me How It Ends), Luiselli demonstrates how callousness toward other cultures erodes our own. Her superb novel makes a devastating case for compassion by documenting the tragic shortcomings of the immigration process."

The Source of Self-Regard by Toni Morrison

Here's what Publishers Weekly had to say about The Source of Self-Regard: "Some superb pieces headline this rich, if perhaps overstocked, collection of primarily spoken addresses and tributes by Nobel laureate Morrison. Many are prescient and highly relevant to the present political moment. For example, Morrison alludes in 1996 to controversy at the U.S.-Mexico border, writing that 'it is precisely ‘the south’ where walls, fences, armed guards, and foaming hysteria are, at this very moment, gathering.' She focuses, of course, on the issues closest to her heart: racism, the move away from compassion in modern-day society, the often invisible presence of African-Americans in American literature, and her own novels. Some of her strongest pieces are the longest: for example, her talk on Gertrude Stein, and her two essays on race in literature, 'Black Matter(s)' and 'Unspeakable Things Unspoken' are must-reads. The collection is organized thematically, which is helpful, but because the pieces jump around in time, dates would be a valuable addition to the essay titles. And while it is no doubt important to create a comprehensive collection of such a noted figure’s writings, the book, which includes 43 selections, can seem padded and overlong at times. Nevertheless, this thoughtful anthology makes for often unsettling, and relevant, reading."

Mother Winter by Sophia Shalmiyev

Here's what Publishers Weekly had to say about Mother Winter: "In this bold if uneven memoir, Shalmiyev, former nonfiction editor for the Portland Review, writes of being a motherless Russian immigrant, addressing the woman who 'left me for the bottle long before my father took me away to America.' Stitching together lyrical essays, fragmented narratives, and critical commentary, she reflects on 'Elena. Mother. Mama,' whose absence led her to seek 'surrogate mothers for myself: feminists, writers, activists, painters, ballbusters.' Loosely linear with discursive asides, Shalmiyev shares memories of her mother’s drunken promiscuity, her own neglected childhood raised by an enigmatic father, and their emigration from Leningrad to New York in 1990. After her arrival in America at age 11, the narrative becomes more chronological and focused. Shalmiyev describes her college years in Seattle as a sex worker; a fruitless trip to Russia to find Elena; and her subsequent marriage, miscarriage, and role as mother; she intersperses these accounts with musings on art, feminism, Russian history, and the work of Pauline Réage, Anaïs Nin, and Susan Sontag (whose son was raised by his father, 'purposefully, unlike my mom, so that she can think clearly and write'). Shalmiyev’s prose can be brilliant, but at times overreaches ('Father never got wintery feet' instead of, simply, cold feet), and the book’s ragged continuity stalls any momentum. This ambitious contemplation on a child’s unreciprocated love for her mother trips over its own story, resulting in an ambiguous, unresolved work."

The Cassandra by Sharma Shields

Here's what Publishers Weekly had to say about The Cassandra: "Shields (The Sasquatch Hunter’s Almanac) repurposes the Greek myth of Cassandra in this alluring, phantasmagoric story of a clairvoyant secretary working at a secret research facility during WWII. Eighteen-year-old Mildred Groves frequently has strange, dark dreams and visions that she can’t escape. After running away from her home in rural Washington, she joins the Women’s Army Corps and applies for a job at the mysterious Hanford research facility on the Columbia River. Hanford was established to support the war effort, but no one understands what is being made in the large compound. Mildred cautiously tries to keep her head down, making friends and avoiding unwanted attention from male colleagues. However, she’s prone to bouts of sleepwalking and having disturbing visions of skeletons and corpses, which become more ominous when she overhears snippets of information revealing that the facility is processing plutonium for the atomic bomb. Shields incorporates a strong feminist undercurrent, and the constant objectification of and casual workplace violence against the women of Hanford often makes for uncomfortable reading. Unfortunately, narrative suspense will be lessened for readers with basic knowledge of WWII history or the Cassandra myth. There is little redemption in Mildred’s story, a conclusion foreshadowed from the start. With a plucky, charismatic narrator and vivid scenes incorporating the history of a real WWII facility, Shield’s novel digs into the destructive arrogance of war."

The Heavens by Sandra Newman

Here's what Publishers Weekly had to say about The Heavens: "In Newman’s stellar novel (following The Country of Ice Cream Star), a woman’s ability to travel back in time in dreams—specifically, to 16th-century Britain—morphs into a world-altering liability. Kate, an art school dropout living in Brooklyn in 2000, has since childhood entered alternate worlds as she sleeps; but the dreams shift and intensify when, in her 20s, she meets and begins dating Ben, a grounded PhD student. Almost nightly Kate becomes Emilia, a pregnant Italian Jew from a family of court musicians, who escapes plague-ridden London in search of a means to save mankind. When Emilia becomes acquainted with melancholy actor Will, the resulting butterfly effect alters countless details of the present, from the president to the death of Ben’s mother. As Kate’s dream relationship with Will becomes increasingly involved (and hers with Ben twists into something strained and painful) visions of a post-apocalyptic world pepper her thoughts. While the world shifts, Kate must untangle the significance of her dreams and their implications for the future. Newman’s novel expertly marries historical and contemporary, plumbing the rich, all-too-human depths of present-day New York and early modern England, and racing toward a well-executed peak. But it’s the evolution of Kate and Ben’s relationship that serves as the book’s emotional anchor, making for a fantastic, ingenious novel."

Death Is Hard Work by Khaled Khalifa

Here's what Publishers Weekly had to say about Death Is Hard Work: "Khalifa’s novel compellingly tackles the strain of responsibility felt by a man in war-torn Syria. After his father, Abdel Latif, dies in hospital, 40-something Bolbol gathers his estranged siblings Hussein and Fatima and, with the corpse in the back of Hussein’s minibus, sets off from Damascus to honor Abdel’s deathbed wish to be buried alongside his sister in the village of Anabiya. Though the distance is short, the quartet’s quest is frequently interrupted by violence and corrupt military checkpoints, forcing the journey to stretch over days, during which time Abdel’s body bloats beneath its burial shroud. Khalifa (No Knives in the Kitchens of This City) punctuates repetitious roadblocks with segues detailing the histories of all four characters. For example, after taking refuge at the home of a former girlfriend, Bolbol reminisces about his father’s own pursuits of an old flame; and later, Hussein’s teenage abandonment of his parents and siblings crops up while their adult counterparts contemplate the purpose of fulfilling Abdel’s request. The narrative choice to summarize conversation indirectly, rather than placing the dialogue directly on the page, might distract some readers. Nonetheless, the novel is at times harrowing—the family flees wild dogs and faces masked guards—and serves as a reminder of the devastation of war and the power of integrity."

Rutting Season by Mandeliene Smith

Here's what Publishers Weekly had to say about Rutting Season: "In Smith’s unsettling debut, characters must confront the most basic, animal sides of themselves as they navigate crisis and tragedy, whether it is a husband’s sudden death, workplace tension, or a police face-off. In the title story, Carl’s boss Ray is constantly giving him a hard time, and one incident in front of Ray’s work crush may be the final straw. 'The Someday Cat' and 'You the Animal' make for an intriguing pair of stories—though they both center on the same climactic moment, they are told from two opposing viewpoints. In 'The Someday Cat,' Janie’s siblings are being put up for adoption one by one, and so her mother brings home a kitten to placate the children who are left. In 'You the Animal,' readers meet Jared, who’s about to be married and on the verge of quitting his job at the Department of Children and Families, which is where readers learn there’s something a little more sinister at play at Janie’s house. At their best, Smith’s characters skate the razor-thin line of brutality in a way that’s both chilling and compelling, although secondary characters too often come across as one-dimensional. Still, this collection proves Smith is an uncommonly talented writer with a particularly sharp eye for the serrated edge of human nature."

Northern Lights by Raymond Strom

Here's what Publishers Weekly had to say about Northern Lights: "Strom’s challenging debut follows recent high school graduate Shane’s roundabout search for his mother. When his uncle kicks him out of the house in the summer of 1997, Shane goes looking for his mother, who abandoned him years before. He tracks her to the small, rust belt town of Holm, Minn., where the locals react suspiciously to his androgynous looks and long hair. He falls in with erratic drug dealer J and angry, spiteful Jenny, who introduce him to increasingly serious drugs. When not getting high with them, Shane incurs the unbidden wrath and terrifying threats of wannabe Klansman Sven Svenson and pursues a confusing sexual relationship with Russell, who only seeks Shane out when drunk. Despite Shane’s plans to leave Holm in the fall for college, he becomes attached. When he finally gets a lead on his mother’s whereabouts and leaves town to pursue it, Jenny’s desperate measures to help her drug-addled mother lead to horrifying consequences. Strom’s insightful navigation of family trauma, sexual identity, and small-town despair blends with his chilling depictions of drug abuse. This bleak, unsentimental novel will resonate with readers who like gritty coming-of-age tales."

Also on shelves: Nothing but the Night by Stoner author John Williams.

February Preview: The Millions Most Anticipated (This Month)

We wouldn’t dream of abandoning our vast semi–annual Most Anticipated Book Previews, but we thought a monthly reminder would be helpful (and give us a chance to note titles we missed the first time around). Here’s what we’re looking out for this month—for more February titles, check out our First-Half Preview. Let us know what you’re looking forward to in the comments!

Want to learn more about upcoming titles? Then go read our most recent book preview. Want to help The Millions keep churning out great books coverage? Then sign up to be a member today.

Black Leopard, Red Wolf by Marlon James: Following up his Man Booker Prize for A Brief History of Seven Killings, James has written the first book in what is to be an epic trilogy that is part Lord of the Rings, part Game of Thrones, and part Black Panther. In this first volume, a band of mercenaries—made up of a witch, a giant, a buffalo, a shape-shifter, and a bounty hunter who can track anyone by smell (his name is Tracker)—are hired to find a boy, missing for three years, who holds special interest for the king. (Janet)

Where Reasons End by Yiyun Li: Where Reasons End is the latest novel by the critically acclaimed author of Dear Friend, from My Life I Write to You in Your Life. Li creates this fictional space where a mother can have an eternal, carefree conversation with her child Nikolai, who commits suicide at the age of 16. Suffused with intimacy and deepest sorrows, the book captures the affections and complexity of parenthood in a way that has never been portrayed before. (Jianan)

The Collected Schizophrenias by Esmé Weijun Wang: Wang writes brilliantly and beautifully about lives lived with mental illness. Her first novel, The Border of Paradise, traces a family through generations, revealing the ways each becomes inheritors of the previous generation’s isolation and depression. In The Collected Schizophrenias, her first essay collection (for which she was awarded the Whiting Award and Greywolf Nonfiction Prize), Wang draws from her experience as both patient and speaker/advocate navigating the vagaries of the mental healthcare system while also shedding light on the ways it robs patients of autonomy. What’s most astonishing is how Wang writes with such intelligence, insight, and care about her own struggle to remain functional while living with schizoaffective disorder. (Anne)

American Spy by Lauren Wilkinson: It’s the mid-1980s and American Cold War adventurism has set its sights on the emerging west African republic of Burkina Faso. There’s only one problem: the agent sent to help swing things America’s way is having second, and third, thoughts. The result is an engaging and intelligent stew of espionage and post-colonial political agency, but more important, a confessional account examining our baser selves and our unscratchable itch to fight wars that cannot be won. (Il’ja)

Lost Children Archive by Valeria Luiselli: The two-time finalist for the National Book Critic’s Circle Award has written a road novel for America in the 21st century. In the book, a family of four set out from their home in New York to visit a place in Arizona called Apacheria, a.k.a. the region once inhabited by the Apache tribe. On their way down south, the family reveals their own set of long-simmering conflicts, while the radio gives updates on an “immigration crisis” at the border. (Thom)

The White Book by Han Kang (translated by Deborah Smith): In 2016, Kang’s stunning novel The Vegetarian won the Man Booker Prize; in 2018, she drew Man Booker attention again with her autobiographical work The White Book. There are loose connections between the two—both concern sisters, for one, and loss, and both feature Han’s beautiful, spare prose—but The White Book is less a conventional story and more like a meditation in fragments. Written about and to the narrator’s older sister, who died as a newborn, and about the white objects of grief, Han’s work has been likened to “a secular prayer book,” one that “investigates the fragility, beauty and strangeness of life.” (Kaulie)

Bangkok Wakes to Rain by Pitchaya Sudbanthad: NYFA Fellow Sudbanthad’s debut novel, Bangkok Wakes to Rain, has already been hailed as “important, ambitious, and accomplished,” by Mohsin Hamid, and a book that “brilliantly sounds the resonant pulse of the city in a wise and far-reaching meditation on home,” by Claire Vaye Watkins. This polyphonic novel follows myriad characters—from a self-exiled jazz pianist to a former student revolutionary—through the thresholds of Bangkok’s past, present, and future. Sudbanthad, who splits his time between Bangkok and New York, says he wrote the novel by letting his mind wander the city of his birth: “I arrived at the site of a house that, to me, became a theatrical stage where characters…entered and left; I followed them, like a clandestine voyeur, across time and worlds, old and new.” (Anne)

The Source of Self-Regard by Toni Morrison: A new collection of nonfiction–speeches, essays, criticism, and reflections–from the Nobel-prize winning Morrison. Publishers Weekly says “Some superb pieces headline this rich collection…Prescient and highly relevant to the present political moment…” (Lydia)

Bowlaway by Elizabeth McCracken: It’s hard to believe it’s been 20 years since McCracken published her first novel, The Giant’s House, perhaps because, since then, she’s given us two brilliant short story collections and one of the most powerful memoirs in recent memory. Her fans will no doubt rejoice at the arrival of this second novel, which follows three generations of a family in a small New England town. Bowlaway refers to a candlestick bowling alley that Publishers Weekly, in its starred review, calls “almost a character, reflecting the vicissitudes of history that determine prosperity or its opposite.” In its own starred review, Kirkus praises McCracken’s “psychological acuity.” (Edan)

All My Goodbyes by Mariana Dimópulos (translated by Alice Whitmore): Argentinian writer Dimópulos’s first book in English is a novel that focuses on a narrator who has been traveling for a decade. The narrator reflects on her habit of leaving family, countries, and lovers. And when she decides to commit to a relationship, her lover is murdered, adding a haunting and sorrowful quality to her interiority. Julie Buntin writes, “The scattered pieces of her story—each of them wonderfully distinct, laced with insight, violence, and sensuality—cohere into a profound evocation of restlessness, of the sublime and imprisoning act of letting go.” (Zoë)

The Hundred Wells of Salaga by Ayesha Harruna Attah: An account of 19th-century Ghana, the novel follows twoyoung girls, Wurche and Aminah, who live in the titular city which is a notorious center preparing people for sale as slaves to Europeans and Americans. Attah’s novel gives a texture and specificity to the anonymous tales of the Middle Passage, with critic Nadifa Mohamad writing in The Guardian that “One of the strengths of the novel is that it complicates the idea of what ‘African history’ is.” (Ed)

The Age of Light by Whitney Scharer: This much sought-after debut, which was the object of a bidding war, is based on the life of Lee Miller, a Vogue model turned photographer who decided she would rather “take a picture than be one.” The novel focuses on Miller’s tumultuous romance with photographer Man Ray in early 1930s Paris, as Miller made the transition from muse to artist. Early reviews suggests that the novel more than lives up to its promise, with readers extolling its complicated heroine and page-turning pacing. (Hannah)

Adèle by Leila Slimani (translated by Sam Taylor): Slimani, who won the Prix Goncourt in 2016, became famous after publishing Dans le jardin de l’ogre, which is now being translated and published in English as Adèle. The French-Moroccon novelist’s debut tells the story of a titular heroine whose burgeoning sex addiction threatens to ruin her life. Upon winning an award in Morocco for the novel, Slimani said its primary focus is her character’s “loss of self.” (Thom)

Notes From a Black Woman’s Diary by Kathleen Collins: Not long after completing her first feature film, Losing Ground, in 1982, Collins died from breast cancer at age 46. In 2017, her short story collection about the lives and loves of black Americans in the 1960s, Whatever Happened to Interracial Love?, was published to ringing critical acclaim. Now comes Notes From a Black Woman’s Diary, which is much more than the title suggests. In addition to autobiographical material, the book includes fiction, plays, excerpts from an unfinished novel, and the screenplay of Losing Ground, with extensive directorial notes. This book is sure to burnish Collins’s flourishing posthumous reputation. (Bill)

Mother Winter by Sophia Shalmiyev: This debut is the memoir of a young woman’s life shaped by unrelenting existential terror. The story is told in fragmentary vignettes beginning with Shalmiyev’s fraught emigration as a young child from St. Petersburg, Russia to the United States, leaving behind the mother who had abandoned her. It closes with her resolve to find her estranged mother again. (Il’ja)

The Cassandra by Sharma Shields: Mildred Groves, The Cassandra’s titular prophetess, sometimes sees flashes of the future. She is also working at the top-secret Hanford Research Center in the 1940s, where the seeds of atomic weapons are sown and where her visions are growing more horrifying—and going ignored at best, punished at worst. Balancing thorough research and mythic lyricism, Shields’s novel is a timely warning of what happens when warnings go unheeded. (Kaulie)

A People’s Future of the United States edited by Victor LaValle and John Joseph Adams: An anthology of 25 speculative stories from a range of powerful storytellers, among them Maria Dahvana Headley, Daniel José Older, and Alice Sola Kim. LaValle and Adams sought stories that imagine a derailed future—tales that take our fractured present and make the ruptures even further. Editor LaValle, an accomplished speculative fiction writer himself (most recently The Changeling, and my personal favorite, the hilarious and booming Big Machine), is the perfect writer to corral these stories. LaValle has said “one of the great things about horror and speculative fiction is that you are throwing people into really outsized, dramatic situations a lot…[including] racism and sexism and classism, biases against the mentally ill”—the perfect description for this dynamic collection. (Nick R.)

[millions_ad]

Nothing but the Night by John Williams: The John Williams ofStoner fame revival continues with the reissue of his first novel by NYRB, first published in 1948, a story dealing with mental illness and trauma with echoes of Greek tragedy. (Lydia)

Vacuum in the Dark by Jen Beagin: Whiting Award winner Beagin is back with a sequel to her debut novel, Pretend I'm Dead. Two-years older, Mona is living in New Mexico and working as a cleaning woman. In an attempt to start over, Mona must heal wounds both new and old—and figure out who she wants to be. Dark, sharp, and poignant, Publishers Weekly's starred review calls the novel "viciously smart and morbidly funny." (Carolyn)

Willa & Hesper by Amy Feltman: Feltman's debut coming-of-age novel follows two queer woman who meet at their MFA program, fall in love, and then break up. In an effort to heal, both leave New York and travel to their respective ancestral homelands: Germany (Willa) and Tbilisi, Georgia (Hesper) Author Crystal Hana Kim called the novel "a lyrical, timely story about love, heartbreak, and healing." (Carolyn)

The Good Immigrant edited by Nikesh Shukla and Chimene Suleyman: In a follow-up to their UK edition, editors Shukla (The One Who Wrote Destiny) and Suleyman (Outside Looking On) gather 26 writers and scholars to write on the immigrant experience—many of which are in response to post-2016 America—including Porochista Khakpour, Teju Cole, Alexander Chee, and Jenny Zhang. With "joy, empathy, and fierceness," Publishers Weekly's starred review called the collection "a gift for anyone who understands or wants to learn about the breadth of experience among immigrants to the U.S." (Carolyn)

Most Anticipated: The Great First-Half 2019 Book Preview

As you learned last week, The Millions is entering into a new, wonderful epoch, a transition that means fretting over the Preview is no longer my purview. This is one of the things I’ll miss about editing The Millions: it has been a true, somewhat mind-boggling privilege to have an early look at what’s on the horizon for literature. But it’s also a tremendous relief. The worst thing about the Preview is that a list can never be comprehensive—we always miss something, one of the reasons that we established the monthly previews, which will continue—and as a writer I know that lists are hell, a font of anxiety and sorrow for other writers.

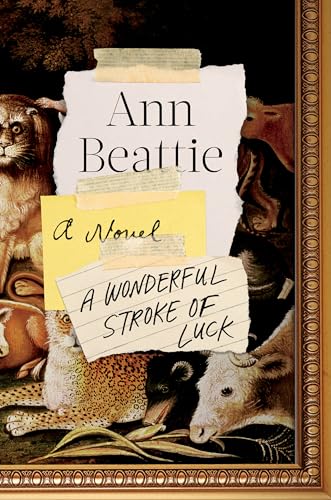

That said, the technical term for this particular January-through-June list is Huge Giant Monster. Clocking in at more than 120 books, it is quite simply, too long. (If I were still the editor and he were still the publisher, beloved site founder C. Max Magee would be absolutely furious with me.) But this over-abundance means blessings for all of us as readers. The first half of 2019 brings new books from Millions contributing editor Chigozie Obioma, and luminaries like Helen Oyeyemi, Sam Lipsyte, Marlon James, Yiyun Li, and Ann Beattie. There are mesmerizing debuts. Searing works of memoir and essay. There’s even a new book of English usage, fodder for your future fights about punctuation.