Mentioned in:

A Year in Reading: 2024

Welcome to the 20th (!) installment of The Millions' annual Year in Reading series, which gathers together some of today's most exciting writers and thinkers to share the books that shaped their year. YIR is not a collection of yearend best-of lists; think of it, perhaps, as an assemblage of annotated bibliographies. We've invited contributors to reflect on the books they read this year—an intentionally vague prompt—and encouraged them to approach the assignment however they choose.

In writing about our reading lives, as YIR contributors are asked to do, we inevitably write about our personal lives, our inner lives. This year, a number of contributors read their way through profound grief and serious illness, through new parenthood and cross-country moves. Some found escape in frothy romances, mooring in works of theology, comfort in ancient epic poetry. More than one turned to the wisdom of Ursula K. Le Guin. Many describe a book finding them just when they needed it.

Interpretations of the assignment were wonderfully varied. One contributor, a music critic, considered the musical analogs to the books she read, while another mapped her reads from this year onto constellations. Most people's reading was guided purely by pleasure, or else a desire to better understand events unfolding in their lives or larger the world. Yet others centered their reading around a certain sense of duty: this year one contributor committed to finishing the six Philip Roth novels he had yet to read, an undertaking that he likens to “eating a six-pack of paper towels.” (Lucky for us, he included in his essay his final ranking of Roth's oeuvre.)

The books that populate these essays range widely, though the most commonly noted title this year was Tony Tulathimutte’s story collection Rejection. The work of newly minted National Book Award winner Percival Everett, particularly his acclaimed novel James, was also widely read and written about. And as the genocide of Palestinians in Gaza enters its second year, many contributors sought out Isabella Hammad’s searing, clear-eyed essay Recognizing the Stranger.

Like so many endeavors in our chronically under-resourced literary community, Year in Reading is a labor of love. The Millions is a one-person editorial operation (with an invaluable assist from SEO maven Dani Fishman), and producing YIR—and witnessing the joy it brings contributors and readers alike—has been the highlight of my tenure as editor. I’m profoundly grateful for the generosity of this year’s contributors, whose names and entries will be revealed below over the next three weeks, concluding on Wednesday, December 18. Be sure to subscribe to The Millions’ free newsletter to get the week’s entries sent straight to your inbox each Friday.

—Sophia Stewart, editor

Becca Rothfeld, author of All Things Are Too Small

Carvell Wallace, author of Another Word for Love

Charlotte Shane, author of An Honest Woman

Brianna Di Monda, writer and editor

Nell Irvin Painter, author of I Just Keep Talking

Carrie Courogen, author of Miss May Does Not Exist

Ayşegül Savaş, author of The Anthropologists

Zachary Issenberg, writer

Tony Tulathimutte, author of Rejection

Ann Powers, author of Traveling: On the Path of Joni Mitchell

Lidia Yuknavitch, author of Reading the Waves

Nicholas Russell, writer and critic

Daniel Saldaña París, author of Planes Flying Over a Monster

Lili Anolik, author of Didion and Babitz

Deborah Ghim, editor

Emily Witt, author of Health and Safety

Nathan Thrall, author of A Day in the Life of Abed Salama

Lena Moses-Schmitt, author of True Mistakes

Jeremy Gordon, author of See Friendship

John Lee Clark, author of Touch the Future

Ellen Wayland-Smith, author of The Science of Last Things

Edwin Frank, publisher and author of Stranger Than Fiction

Sophia Stewart, editor of The Millions

A Year in Reading Archives: 2023, 2022, 2021, 2020, 2019, 2018, 2017, 2016, 2015, 2014, 2013, 2011, 2010, 2009, 2008, 2007, 2006, 2005

The Great Fall 2024 Book Preview

With the arrival of autumn comes a deluge of great books. Here you'll find a sampling of new and forthcoming titles that caught our eye here at The Millions, and that we think might catch yours, too. Some we’ve already perused in galley form; others we’re eager to devour based on their authors, plots, or subject matters. We hope your next fall read is among them.

—Sophia Stewart, editor

October

Season of the Swamp by Yuri Herrera, tr. Lisa Dillman [F]

What it is: An epic, speculative account of the 18 months that Benito Juárez spent in New Orleans in 1853-54, years before he became the first and only Indigenous president of Mexico.

Who it's for: Fans of speculative history; readers who appreciate the magic that swirls around any novel set in New Orleans. —Claire Kirch

The Black Utopians by Aaron Robertson [NF]

What it is: An exploration of Black Americans' pursuit and visions of utopia—both ideological and physical—that spans the Reconstruction era to the present day and combines history, memoir, and reportage.

Who it's for: Fans of Saidiya Hartman's Wayward Lives, Beautiful Experiments and Kristen R. Ghodsee's Everyday Utopia. —Sophia M. Stewart

The Third Realm by Karl Ove Knausgaard, tr. Martin Aitken [F]

What it is: The third installment in Knausgaard's Morning Star series, centered on the appearance of a mysterious new star in the skies above Norway.

Who it's for: Real Knausgaard heads only—The Wolves of Eternity and Morning Star are required reading for this one. —SMS

Brown Women Have Everything by Sayantani Dasgupta [NF]

What it is: Essays on the contradictions and complexities of life as an Indian woman in America, probing everything from hair to family to the joys of travel.

Who it's for: Readers of Durga Chew-Bose, Erika L. Sánchez, and Tajja Isen. —SMS

The Plot Against Native America by Bill Vaughn [F]

What it is: The first narrative history of Native American boarding schools— which aimed "civilize" Indigenous children by violently severing them from their culture— and their enduring, horrifying legacy.

Who it's for: Readers of Ned Blackhawk and Kathleen DuVal. —SMS

The Mighty Red by Louise Erdrich [F]

What it is: Erdrich's latest novel set in North Dakota's Red River Valley is a tale of the intertwined lives of ordinary people striving to survive and even thrive in their rural community, despite environmental upheavals, the 2008 financial crisis, and other obstacles.

Who it's for: Readers of cli-fi; fans of Linda LeGarde Grover and William Faulkner. —CK

The Position of Spoons by Deborah Levy [NF]

What it is: The second book from Levy in as many years, diverging from a recent streak of surrealist fiction with a collection of essays marked by exceptional observance and style.

Who it's for: Close lookers and the perennially curious. —John H. Maher

The Bog Wife by Kay Chronister [F]

What it's about: The Haddesley family has lived on the same West Virginia bog for centuries, making a supernatural bargain with the land—a generational blood sacrifice—in order to do so—until an uncovered secret changes everything.

Who it's for: Readers of Karen Russell and Jeff VanderMeer; anyone who has ever used the phrase "girl moss." —SMS

The Great When by Alan Moore [F]

What it's about: When an 18-year old book reseller comes across a copy of a book that shouldn’t exist, it threatens to upend not just an already post-war-torn London, but reality as we know it.

Who it's for: Anyone looking for a Sherlock Holmes-style mystery dipped in thaumaturgical psychedelia. —Daniella Fishman

The Message by Ta-Nehisi Coates [NF]

What it's about: One of our sharpest critical thinkers on social justice returns to nonfiction, nearly a decade after Between the World and Me, visiting Dakar, to contemplate enslavement and the Middle Passage; Columbia, S.C., as a backdrop for his thoughts on Jim Crow and book bans; and the Israeli-occupied West Bank, where he sees contemporary segregation in the treatment of Palestinians.

Who it’s for: Fans of James Baldwin, George Orwell, and Angela Y. Davis; readers of Nikole Hannah-Jones’s The 1619 Project and Isabel Wilkerson’s Caste, to name just a few engagements with national and racial identity. —Nathalie op de Beeck

Abortion by Jessica Valenti [NF]

What it is: Columnist and memoirist Valenti, who tracks pro-choice advocacy and attacks on the right to choose in her Substack, channels feminist rage into a guide for freedom of choice advocacy.

Who it’s for: Readers of Robin Marty’s The New Handbook for a Post-Roe America, #ShoutYourAbortion proponents, and followers of Jennifer Baumgartner’s [I Had an Abortion] project. —NodB

Gifted by Suzuki Suzumi, tr. Allison Markin Powell [F]

What it's about: A young sex worker in Tokyo's red-light district muses on her life and recounts her abusive mother's final days, in what is Suzuki's first novel to be translated into English.

Who it's for: Readers of Susan Boyt and Mieko Kanai; fans of moody, introspective fiction; anyone with a fraught relationship to their mother. —SMS

Childish Literature by Alejandro Zambra, tr. Megan McDowell [F]

What it is: A wide-ranging collection of stories, essays, and poems that explore childhood, fatherhood, and family.

Who it's for: Fans of dad lit (see: Lucas Mann's Attachments, Keith Gessen's Raising Raffi, Karl Ove Knausgaard's seasons quartet, et al). —SMS

Books Are Made Out of Books ed. Michael Lynn Crews [NF]

What it is: A mining of the archives of the late Cormac McCarthy with a focus on the famously tight-lipped author's literary influences.

Who it's for: Anyone whose commonplace book contains the words "arquebus," "cordillera," or "vinegaroon." —JHM

Slaveroad by John Edgar Wideman [F]

What it is: A blend of memoir, fiction, and history that charts the "slaveroad" that runs through American history, spanning the Atlantic slave trade to the criminal justice system, from the celebrated author of Brothers and Keepers.

Who it's for: Fans of Clint Smith and Ta-Nehisi Coates. —SMS

Linguaphile by Julie Sedivy [NF]

What it's about: Linguist Sedivy reflects on a life spent loving language—its beauty, its mystery, and the essential role it plays in human existence.

Who it's for: Amateur (or professional) linguists; fans of the podcast A Way with Words (me). —SMS

An Image of My Name Enters America by Lucy Ives [NF]

What it is: A collection of interrelated essays that connect moments from Ives's life to larger questions of history, identity, and national fantasy,

Who it's for: Fans of Ives, one of our weirdest and most wondrous living writers—duh; anyone with a passing interest in My Little Pony, Cold War–era musicals, or The Three Body Problem, all of which are mined here for great effect. —SMS

Women's Hotel by Daniel Lavery [F]

What it is: A novel set in 1960s New York City, about the adventures of the residents of a hotel providing housing for young women that is very much evocative of the real-life legendary Barbizon Hotel.

Who it's for: Readers of Mary McCarthy's The Group and Rona Jaffe's The Best of Everything. —CK

The World in Books by Kenneth C. Davis [NF]

What it is: A guide to 52 of the most influential works of nonfiction ever published, spanning works from Plato to Ida B. Wells, bell hooks to Barbara Ehrenreich, and Sun Tzu to Joan Didion.

Who it's for: Lovers of nonfiction looking to cover their canonical bases. —SMS

Blue Light Hours by Bruna Dantas Lobato [F]

What it's about: Through the emanating blue-glow of their computer screens, a mother and daughter, four-thousand miles apart, find solace and loneliness in their nightly Skype chats in this heartstring-pulling debut.

Who it's for: Someone who needs to be reminded to CALL YOUR MOTHER! —DF

Riding Like the Wind by Iris Jamahl Dunkle [NF]

What it is: The biography of Sanora Babb, a contemporary of John Steinbeck's whose field notes and interviews with Dust Bowl migrants Steinbeck relied upon to write The Grapes of Wrath.

Who it's for: Steinbeck fans and haters alike; readers of Kristin Hannah's The Four Winds and the New York Times Overlooked column; anyone interested in learning more about the Dust Bowl migrants who fled to California hoping for a better life. —CK

Innie Shadows by Olivia M. Coetzee [F]

What it is: a work of crime fiction set on the outskirts of Cape Town, where a community marred by violence seeks justice and connection; also the first novel to be translated from Kaaps, a dialect of Afrikaans that was until recently only a spoken language.

Who it's for: fans of sprawling, socioeconomically-attuned crime dramas a la The Wire. —SMS

Dorothy Parker in Hollywood by Gail Crowther [NF]

What it is: A history of the famous wit—and famous New Yorker—in her L.A. era, post–Algonquin Round Table and mid–Red Scare.

Who it's for: Owners of a stack of hopelessly dog-eared Joan Didion paperbacks. —JHM

The Myth of American Idealism by Noam Chomsky and Nathan J. Robinson [NF]

What it is: A potent critique of the ideology behind America's foreign interventions and its status as a global power, and an treatise on how the nation's hubristic pursuit of "spreading democracy" threatens not only the delicate balance of global peace, but the already-declining health of our planet.

Who it's for: Chomskyites; policy wonks and casual critics of American recklessness alike. —DF

Mysticism by Simon Critchley [NF]

What it is: A study of mysticism—defined as an experience, rather than religious practice—by the great British philosopher Critchley, who mines music, poetry, and literature along the way.

Who it's for: Readers of John Gray, Jorge Luis Borges, and Simone Weil. —SMS

Q&A by Adrian Tomine [NF]

What it is: The Japanese American creator of the Optic Nerve comic book series for D&Q, and of many a New Yorker cover, shares his personal history and his creative process in this illustrated unburdening.

Who it’s for: Readers of Tomine’s melancholic, sometimes cringey, and occasionally brutal collections of comics short stories including Summer Blonde, Shortcomings, and Killing and Dying. —NodB

Sonny Boy by Al Pacino [NF]

What it is: Al Pacino's memoir—end of description.

Who it's for: Cinephiles; anyone curious how he's gonna spin fumbling Diane Keaton. —SMS

Seeing Baya by Alice Kaplan [NF]

What it is: The first biography of the enigmatic and largely-forgotten Algerian artist Baya Mahieddine, who first enchanted midcentury Paris as a teenager.

Who it's for: Admirers of Leonora Carrington, Hilma af Klint, Frida Kahlo, and other belatedly-celebrated women painters. —SMS

Absolution by Jeff VanderMeer [F]

What it is: A surprise return to the Area X, the stretch of unforbidding and uncanny coastline in the hit Southern Reach trilogy.

Who it's for: Anyone who's heard this song and got the reference without Googling it. —JHM

The Four Horsemen by Nick Curtola [NF]

What it is: The much-anticipated cookbook from the team behind Brooklyn's hottest restaurant (which also happens to be co-owned by James Murphy of LCD Soundsystem).

Who it's for: Oenophiles; thirty-somethings who live in north Williamsburg (derogatory). —SMS

Seeing Further by Esther Kinsky, tr. Caroline Schmidt [F]

What it's about: An unnamed German woman embarks on the colossal task of reviving a cinema in a small Hungarian village.

Who it's for: Fans of Jenny Erpenbeck; anyone charmed by Cinema Paradiso (not derogatory!). —SMS

Ripcord by Nate Lippens [NF]

What it's about: A novel of class, sex, friendship, and queer intimacy, written in delicious prose and narrated by a gay man adrift in Milwaukee.

Who it's for: Fans of Brontez Purnell, Garth Greenwell, Alexander Chee, and Wayne Koestenbaum. —SMS

The Use of Photography by Annie Ernaux and Marc Marie, tr. Alison L. Strayer [NF]

What it's about: Ernaux's love affair with Marie, a journalist, while she was undergoing treatment for cancer, and their joint project to document their romance.

Who it's for: The Ernaux hive, obviously; readers of Sontag's On Photography and Janet Malcolm's Still Pictures. —SMS

Nora Ephron at the Movies by Ilana Kaplan [NF]

What it is: Kaplan revisits Nora Ephron's cinematic watersheds—Silkwood, Heartburn, When Harry Met Sally, You've Got Mail, and Sleepless in Seattle—in this illustrated book. Have these iconic stories, and Ephron’s humor, weathered more than 40 years?

Who it’s for: Film history buffs who don’t mind a heteronormative HEA; listeners of the Hot and Bothered podcast; your coastal grandma. —NodB

[millions_email]

The Philosophy of Translation by Damion Searls [NF]

What it is: A meditation on the act and art of translation by one of today's most acclaimed practitioners, best known for his translations of Fosse, Proust, et al.

Who it's for: Regular readers of Words Without Borders and Asymptote; professional and amateur literary translators alike. —SMS

Salvage by Dionne Brand

What it is: A penetrating reevaluation of the British literary canon and the tropes once shaped Brand's reading life and sense of self—and Brand’s first major work of nonfiction since her landmark A Map to the Door of No Return.

Who it's for: Readers of Christina Sharpe's Ordinary Notes and Elizabeth Hardwick's Seduction and Betrayal. —SMS

Masquerade by Mike Fu [F]

What it's about: Housesitting for an artist friend in present-day New York, Meadow Liu stumbles on a novel whose author shares his name—the first of many strange, haunting happenings that lead up to the mysterious disappearance of Meadow's friend.

Who it's for: fans of Ed Park and Alexander Chee. —SMS

November

The Beggar Student by Osamu Dazai, tr. Sam Bett [F]

What it is: A novella in the moody vein of Dazai’s acclaimed No Longer Human, following the 30-something “fictional” Dazai into another misadventure spawned from a hubristic spat with a high schooler.

Who it's for: Longtime readers of Dazai, or new fans who discovered the midcentury Japanese novelist via TikTok and the Bungo Stray Dogs anime. —DF

In Thrall by Jane DeLynn [F]

What it is: A landmark lesbian bildungsroman about 16-year-old Lynn's love affair with her English teacher, originally published in 1982.

Who it's for: Fans of Joanna Russ's On Strike Against God and Edmund White's A Boy's Own Story —SMS

Washita Love Child by Douglas Kent Miller [NF]

What it is: The story of Jesse Ed Davis, the Indigenous musician who became on of the most sought after guitarists of the late '60s and '70s, playing alongside B.B. King, Bob Dylan, John Lennon, and more.

Who it's for: readers of music history and/or Indigenous history; fans of Joy Harjo, who wrote the foreword. —SMS

Set My Heart on Fire by Izumi Suzuki, tr. Helen O'Horan [F]

What it is: Gritty, sexy, and wholly rock ’n’ roll, Suzuki’s first novel translated into English (following her story collection, Hit Parade of Tears) follows 20-year-old Izumi navigating life, love, and music in the underground scene in '70s Japan.

Who it's for: Fans of Meiko Kawakami, Ursula K. Le Guin, and Marlowe Granados's Happy Hour. —DF

Didion & Babitz by Lili Anolik [NF]

What it is: A dual portrait of Joan Didion and Eve Babitz, who are so often compared to—and pitted against—each other on the basis of their mutual Los Angeles milieu.

Who it's for: Fans or haters of either writer (the book is fairly pro-Babitz, often at Didion's expense); anyone who has the Lit Hub Didion tote bag. —SMS

The Endless Refrain by David Rowell [NF]

What it's about: How the rise of music streaming, demonitizing of artist revenue, and industry tendency toward nostalgia have laid waste to the musical landscape, and the future of music culture.

Who it's for: Fans of Kyle Chayka, Spence Kornhaber, and Lindsay Zoladz. —SMS

Every Arc Bends Its Radian by Sergio De La Pava [F]

What it is: A mind- and genre-bending detective story set in Cali, Colombia, that blends high-stakes suspense with rigorous philosophy.

Who it's for: Readers of Raymond Chandler, Thomas Pynchon, and Jules Verne. —SMS

Something Close to Nothing by Tom Pyun [F]

What it’s about: At the airport with his white husband Jared, awaiting a flight to Cambodia to meet the surrogate mother carrying their adoptive child-to-be, Korean American Wynn decides parenthood isn't for him, and bad behavior ensues.

Who it’s for: Pyun’s debut is calculated to cut through saccharine depictions of queer parenthood—could pair well with Torrey Peters’s Detransition, Baby. —NodB

Rosenfeld by Maya Kessler [F]

What it is: Kessler's debut—rated R for Rosenfeld—follows one Noa Simmons through the tumultuous and ultimately profound power play that is courting (and having a lot of sex with) the titular older man who soon becomes her boss.

Who it's for: Fans of Sex and the City, Raven Leilani’s Luster, and Coco Mellor’s Cleopatra and Frankenstein. —DF

Lazarus Man by Richard Price [F]

What it is: The former The Wire writer offers yet another astute chronicle of urban life, this time of an ever-changing Harlem.

Who it's for: Fans of Colson Whitehead's Crook Manifesto and Paul Murray's The Bee Sting—and, of course, The Wire. —SMS

Stranger Than Fiction by Edwin Frank [NF]

What it is: An astute curveball of a read on the development and many manifestations of the novel throughout the tumultuous 20th century.

Who it's for: Readers who look at a book's colophon before its title. —JHM

Letters to His Neighbor by Marcel Proust, tr. Lydia Davis

What it is: A collection of Proust’s tormented—and frequently hilarious—letters to his noisy neighbor which, in a diligent translation from Davis, stand the test of time.

Who it's for: Proust lovers; people who live below heavy-steppers. —DF

Context Collapse by Ryan Ruby [NF]

What it is: A self-proclaimed "poem containing a history of poetry," from ancient Greece to the Iowa Workshop, from your favorite literary critic's favorite literary critic.

Who it's for: Anyone who read and admired Ruby's titanic 2022 essay on The Waste Land; lovers of poetry looking for a challenge. —SMS

How Sondheim Can Change Your Life by Richard Schoch [NF]

What it's about: Drama professor Schoch's tribute to Stephen Sondheim and the life lessons to be gleaned from his music.

Who it's for: Sondheim heads, former theater kids, end of list. —SMS

The Serviceberry by Robin Wall Kimmerer [NF]

What it is: 2022 MacArthur fellow and botanist Kimmerer, an enrolled member of the Citizen Potawatomi Nation, (re)introduces audiences to a flowering, fruiting native plant beloved of foragers and gardeners.

Who it’s for: The restoration ecologist in your life, along with anyone who loved Braiding Sweetgrass and needs a nature-themed holiday gift. —NodB

My Heart Belongs in an Empty Big Mac Container Buried Beneath the Ocean Floor by Homeless [F]

What it is: A pseudonymous, tenderly comic novel of blue whales and Golden Arches, mental illness and recovery.

Who it's for: Anyone who finds Thomas Pynchon a bit too staid. —JHM

Yoke and Feather by Jessie van Eerden [NF]

What it's about: Van Eerden's braided essays explore the "everyday sacred" to tease out connections between ancient myth and contemporary life.

Who it's for: Readers of Courtney Zoffness's Spilt Milk and Jeanna Kadlec's Heretic. —SMS

Camp Jeff by Tova Reich [F]

What it's about: A "reeducation" center for sex pests in the Catskills, founded by one Jeffery Epstein (no, not that one), where the dual phenomena of #MeToo and therapyspeak collide.

Who it's for: Fans of Philip Roth and Nathan Englander; cancel culture skeptics. —SMS

Selected Amazon Reviews by Kevin Killian [NF]

What it is: A collection of 16 years of Killian’s funniest, wittiest, and most poetic Amazon reviews, the sheer number of which helped him earn the rarefied “Top 100” and “Hall of Fame” status on the site.

Who it's for: Fans of Wayne Koestenbaum and Dodie Bellamy, who wrote introduction and afterword, respectively; people who actually leave Amazon reviews. —DF

Cher by Cher [NF]

What it is: The first in a two-volume memoir, telling the story of Cher's early life and ascendent career as only she can tell it.

Who it's for: Anyone looking to fill the My Name Is Barbra–sized hole in their heart, or looking for something to tide them over until the Liza memoir drops. —SMS

The City and Its Uncertain Walls by Haruki Murakami, tr. Philip Gabriel [F]

What it is: Murakami’s first novel in over six years returns to the high-walled city from his 1985 story "Hard-Boiled Wonderland and the End of the World" with one man's search for his lost love—and, simultaneously, an ode to libraries and literature itself.

Who it's for: Murakami fans who have long awaited his return to fiction. —DF

American Bulk by Emily Mester [NF]

What it's about: Reflecting on what it means to "live life to the fullest," Mester explores the cultural and personal impacts of America’s culture of overconsumption, from Costco hauls to hoarding to diet culture—oh my!

Who it's for: Lovers of sustainability; haters of excess; skeptics of the title essay of Becca Rothfeld's All Things Are Too Small. —DF

The Icon and the Idealist by Stephanie Gorton [NF]

What it is: A compelling look at the rivalry between Margaret Sanger, of Planned Parenthood fame, and Mary Ware Dennett, who each held radically different visions for the future of birth control.

Who it's for: Readers of Amy Sohn's The Man Who Hated Women and Katherine Turk's The Women of NOW; anyone interested in the history of reproductive rights. —SMS

December

Rental House by Weike Wang [F]

What it's about: Married college sweethearts invite their drastically different families on a Cape Code vacation, raising questions about marriage, intimacy, and kinship.

Who it's for: Fans of Wang's trademark wit and sly humor (see: Joan Is Okay and Chemistry); anyone with an in-law problem.

Woo Woo by Ella Baxter [F]

What it's about: A neurotic conceptual artist loses her shit in the months leading up to an exhibition that she hopes will be her big breakout, poking fun at the tropes of the "art monster" and the "woman of the verge" in one fell, stylish swoop.

Who it's for: Readers of Sheena Patel's I'm a Fan and Chris Kraus's I Love Dick; any woman who is grateful to but now also sort of begrudges Jenny Offil for introducing "art monster" into the lexicon (me). —SMS

Berlin Atomized by Julia Kornberg, tr. Jack Rockwell and Julia Kornberg [F]

What it's about: Spanning 2001 to 2034, three Jewish and downwardly mobile siblings come of age in various corners of the world against the backdrop of global crisis.

Who it's for: Fans of Catherine Lacey's Biography of X and Joshua Cohen's The Netanyahus. —SMS

Sand-Catcher by Omar Khalifah, tr. Barbara Romaine [F]

What it is: A suspenseful, dark satire of memory and nation, in which four young Palestinian journalists at a Jordanian newspaper are assigned to interview an elderly witness to the Nakba, the violent 1948 expulsion of native Palestinians from Israel—but to their surprise, the survivor doesn’t want to rehash his trauma for the media.

Who it’s for: Anyone looking insight—tinged with grim humor—into the years leading up to the present political crisis in the Middle East and the decades-long goal of Palestinian autonomy. —NodB

The Shutouts by Gabrielle Korn [F]

What it's about: In the dystopian future, mysteriously connected women fight to survive on the margins of society amid worsening climate collapse.

Who it's for: Fans of Korn's Yours for the Taking, which takes place in the same universe; readers of Becky Chambers and queer-inflected sci-fi. —SMS

What in Me Is Dark by Orlando Reade [NF]

What it's about: The enduring, evolving influence of Milton's Paradise Lost on political history—and particularly on the work of 12 revolutionary readers, including Malcom X and Hannah Arendt.

Who it's for: English majors and fans of Ryan Ruby and Sarah Bakewell—but I repeat myself. —SMS

The Afterlife Is Letting Go by Brandon Shimoda [NF]

What it's about: Shimoda researches the mass incarceration of Japanese Americans during WWII, and speaks with descendants of those imprisoned, for this essay collection about the “afterlife” of cruelty and xenophobia in the U.S.

Who it’s for: Anyone to ever visit a monument, museum, or designated site of hallowed ground where traumatic events have taken place. —NodB

No Place to Bury the Dead by Karina Sainz Borgo, tr. Elizabeth Bryer [F]

What it's about: When Angustias Romero loses both her children while fleeing a mysterious disease in her unnamed Latin American country, she finds herself in a surreal, purgatorial borderland where she's soon caught in a power struggle.

Who it's for: Fans of Maríana Enriquez and Mohsin Hamid. —SMS

The Rest Is Silence by Augusto Monterroso, tr. Aaron Kerner [F]

What it is: The author of some of the shortest, and tightest, stories in Latin American literature goes long with a metafictional skewering of literary criticism in his only novel.

Who it's for: Anyone who prefers the term "palm-of-the-hand stories" to "flash fiction." —JHM

Tali Girls by Siamak Herawi, tr. Sara Khalili [F]

What it is: An intimate, harrowing, and vital look at the lives of girls and women in an Afghan mountain village under Taliban rule, based on true stories.

Who it's for: Readers of Nadia Hashimi, Akwaeke Emezi, and Maria Stepanova. —SMS

Sun City by Tove Jansson, tr. Thomas Teal [F]

What it's about: During her travels through the U.S. in the 1970s, Jansson became interested in the retirement home as a peculiarly American institution—here, she imagines the tightly knit community within one of them.

Who it's for: Fans of Jansson's other fiction for adults, much of which explores the lives of elderly folks; anyone who watched that documentary about The Villages in Florida. —SMS

Editor's note: We're always looking to make our seasonal book previews more useful to the readers, writers, and critics they're meant to serve. Got an idea for how we can improve our coverage? Tell me about it at sophia@themillions.com.

[millions_email]

A Year in Reading: Anna Wiener

I spent a lot of this year trying to write a book: lying on the floor, making spaghetti, chewing on my fingernails, staring at the wall, reading. I wanted to figure some things out, and surrounded myself with books that I thought would help. Instead of reading them, I got distracted. I read an endless number of articles and essays about politics, technology, politics and technology. I stuffed my brain with information. Wikipedia. I was thinking about Yelp culture and V.C. culture, so I read a lot of Yelp reviews, and a lot of tweets from venture capitalists and nascent venture capitalists. Medium posts. Hacker News.

After a while, this became boring, and I remembered how to read for pleasure. I read, or reread: Red Brick, Black Mountain, White Clay; Things I Don’t Want to Know; Stone Arabia; Asymmetry; Housekeeping; Fierce Attachments; The Maples Stories; Twilight of the Superheroes; Talk Stories; To the Lighthouse; Mating; Imperial San Francisco; The Book of Daniel; White Noise; The Fire Next Time; Close to the Machine. Essays from Happiness, and The Essential Ellen Willis, and The White Album, and Discontent and Its Civilizations, and The Earth Dies Streaming. This Boy’s Life and Stop-Time. I meant to reread Leaving the Atocha Station, but it fell into the bathtub; fine. 10:04. A stack of books about Silicon Valley history, many of which I did not finish; a lot of them told the same stories.

I read a 1971 edition of the Whole Earth Catalog, and the free e-book preview of The Devil Wears Prada, and some, but not all, of The Odyssey, the Emily Wilson translation. I got stoned before bed and read What Was the Hipster?––? I read Eileen and The Recovering and And Now We Have Everything and The Golden State and Chemistry and The Boatbuilder and Normal People and Breaking and Entering and Notes of a Native Son and Bright Lights, Big City and Heartburn and That Kind of Mother and How Fiction Works and Motherhood and Early Work and My Duck Is Your Duck and The Cost of Living and Who Is Rich? and The Mars Room. Some more pleasurable than others but all, or most, satisfying in their own ways.

I read the Amazon reviews for popular memoirs and regretted doing that. I did not read much poetry, and I regret that, too.

A few weeks ago, I read What We Should Have Known: Two Discussions, and No Regrets: Three Discussions. Five discussions! Not enough. I was very grateful for No Regrets, which felt both incomplete and expansive. Reading it was clarifying across multiple axes.

I wish I’d read more this year, or read with more direction, or at the very least kept track. I wish I’d read fewer books published within my lifetime. I wish I’d had more conversations. Staring at the wall is a solitary pursuit. I didn't really figure out what I hoped to understand, namely: time. Time? I asked everyone. Time??? (Structure? Ha-ha.) Whatever. It's fine. Not everything has to be a puzzle, and not everything has a solution. Time did pass.

More from A Year in Reading 2018

Do you love Year in Reading and the amazing books and arts content that The Millions produces year round? We are asking readers for support to ensure that The Millions can stay vibrant for years to come. Please click here to learn about several simple ways you can support The Millions now.

Don’t miss: A Year in Reading 2017, 2016, 2015, 2014, 2013, 2012, 2011, 2010, 2009, 2008, 2007, 2006, 2005

[millions_ad]

Youth and the Eisenberg Uncertainty Principle: Laura van den Berg’s The Isle of Youth

I began this all wrong, so the paragraph you’re reading now is actually a total do-over. Or maybe not “total” – if you swallow certain theories of the universe, a completed draft of that aborted essay exists somewhere in an alternate reality, one which follows the course of my errant lede. As far as I can tell, though, that’s still only a theory. Perhaps it seems a little too perfect that this misstep should transpire in an examination of Laura van den Berg’s second collection of short fiction, as the seven narratives in The Isle of Youth turn again and again at the point-zero restart, obsessed with roads-not-taken and changes so drastic that reality itself seems to skip to a new dimension. Perhaps it seems a little too perfect, but to read The Isle of Youth is to witness how every fresh start only brings a new set of complications.

Can this possibly be my life? Any of the six words in that sentence can hold the stress, and facing some intersection of the preposterous and the mundane, the female narrators in van den Berg’s debut collection (What The World Will Look Like When All The Water Leaves Us) consistently grappled with their own spin on the question. Can THIS possibly be...? An actress settles in a detour town with a stunted career and a terminal boyfriend; an art history student drops out of college to raise her troubled little brother after their parents are killed abroad; a botanist joins a lengthy research mission in Scotland to flee a crumbling relationship. While these women confronted the quotidian fuss of a life they never foresaw, van den Berg played with a counter-level of the unfathomable, situating unseen creatures on the fringe of each narrative: Bigfoot, the mapinguari, the Loch Ness Monster; all these believe-it-or-not haunts proving a minor threat compared to the demands of just getting by.

Before the close of that first book, the procession of tangential monsters threatened to lapse into shtick, and in The Isle of Youth van den Berg forces her characters to stand down life’s bafflements with little more than their own wits, prevarications, and sleight of hand. Without a “Missing Link” to further destabilize reality, in this new batch of stories van den Berg achieves the same dramatic weight by utilizing The Eisenberg Uncertainty Principle.

“By the time you see there’s a decision to be made,” short story master Deborah Eisenberg once wrote, “you can be pretty sure it’s a decision you’ve already made.” Originally I’d decided to use that quote as the opening sentence of this essay, but then I changed my mind after the subsequent paragraphs trailed off into an understory of Eisenberg’s gracefully canted prose, with The Isle of Youth nowhere in sight. What once appeared an ideal opening line now serves as a practical pivot point, clearing the way to set forth how – across three decades of short fiction – Eisenberg has found a way to channel narrative momentum less by plodding points and more by harnessing waves, jarring reality out of focus and gaining force by sharpening it once again.

Cobbled out of all four collections of Eisenberg’s stories, from Transactions in a Foreign Currency (1986) to Twilight of the Superheroes, (2006) The Eisenberg Uncertainty Principle incorporates derivations of The Many Worlds Theory (where all the possible outcomes of each decision and action exist in split copies of reality); the observer-effect (named for the guy who suggested that certainty was impossible since the tools for measurement inevitably impact the object being measured); and Viktor Shklovsky’s formalist principle of ostranenie, or “enstrangement” (wherein an artist recasts the common in a way that allows it to be appreciated anew – such as slipping an innocuous “n” into the word “estrangement” and voilà).

“We really don’t know to what degree time is linear, and under what circumstances,” suggests a mathematical genius in Eisenberg’s “Some Other, Better Otto.” “Is it actually, in fact, manifold? Or pleated? Is it frilly?”

Sure, that same genius was also prone to psychic breaks severe enough to require hospitalization, but that’s just the author being mischievous. Even in her earlier work, from the story of a teen girl who realizes she quibbled away a typical day while unaware her mother was dead to the narrative of a middling concert pianist who wakes in a foreign city after his wife has left him, Eisenberg has constructed her work around overlaps of time, with characters knocked for a loop by the “now-you-see-it, now-you-don’t quality about life that makes one so very nervous.”

The mysteries of time and space don’t resolve with age, observation, or relative sanity; in the post-9/11 title story of Twilight of the Superheroes, a widowed Manhattanite reflects on the “eternal, poignant weariness of youth” while his own sensory grasp of reality often betrays him: “During his waking hours, the food on his plate would abruptly lose its taste, the painting he was studying would bleach off the canvas, the friend he was talking to would turn into a stranger.”

Shklovsky’s oft-repeated quote is that estrangement serves “to make the stone stony,” and Eisenberg makes life lively through that formalist technique of defamiliarization, exploding moments where her characters see their lives in shards of bizarre impossibility, leading her fictions to crystalize at counter-epiphanies – rather than light bulb flashes of enlightenment or moral truth, readers are able to observe how direction takes shape from a blinding overwhelm.

“It is amazing to be able to find out what I want to do at any given moment, out of what seems to be nothing, out of not knowing at all,” says the narrator of Eisenberg’s “Days,” a woman who needs to develop entirely new concepts of time and identity after she quits smoking. “It is secretly and individually thrilling, like being able to open my fist and release into the air a flock of white doves.”

Should anyone in The Isle of Youth loose captive birds from their palm, don’t believe your eyes. Prestidigitators, performers, twins...amid stories of wit and misdirection van den Berg follows in Eisenberg’s suit, equally fascinated with capitulations and recapitulations, simulacra, and the suddenness of disorder. And when all else fails, van den Berg’s characters resort to the layperson’s application of The Many Worlds theory: the good old-fashioned whopper.

“Talking to someone who didn’t know me, who couldn’t separate the truth from the lie, always gave me the most ruthless sense of freedom,” says the narrator of “Acrobat.” That unbound freedom equates to a form of coherent superposition, the theoretical condition of existing in all possible states at once. Imagine two complete strangers who have yet to meet or speak – between them, a limitless world of possibility exists. Superposition, however, immediately collapses on contact: truth or lie, consequences unfold and the infinite gives way.

Distracted by a trio of Parisian street performers, the fib-prone narrator of “Acrobat” fails to hear a rather crucial bit of information about why her husband has decided to leave her right then and there. Among the next available steps, she chooses one of the least likely, following the acrobats from the Jardin de Tuileries to the Champs-Élysées to the Eiffel Tower, stopping at cafés and bistros for cigarettes and meals before finally joining the trio at a house party jammed with costumed contortionists and buskers. Though thoroughly disorienting, “Acrobat” applies The Eisenberg Uncertainty Principle to avoid pure randomness, with the narrator moving forward in time while trying to recapture a missed point. With a billion swirling atoms of possibility and just that one fixed coordinate, a story takes shape as van den Berg brings the unexpected into brilliant focus.

Often the best measure of a presence is the quality of its absence, and “Lessons” is the lone story in The Isle of Youth where van den Berg abandons The Eisenberg Uncertainty Principle, tipping her hand with foreshadowing and narrative ineluctability: a teenage survivalist drags her little brother along to serve as the lookout while she and her cousins pull a series of small-time stickup jobs. Inexorable forces + cute kid in peril = no room to breathe. Leaving a little wiggle room for the reader avoids manipulation, but in “Lessons” the kid’s name is Pinky and he just wants to build a robot and however many outcomes exist, you can be certain that none bode well.

Throughout the rest of The Isle of Youth, van den Berg’s protagonists continue to ask can this possibly be my life, with only the thread of family ties binding them to a prior state of being. Without ever dipping into fabulism or the surreal, the twin-swapping title story and the deceptively profound “Opa-Locka” challenge perceived reality; in the latter, sisters at loose ends decide to start their own detective agency, but as the mismatched duo puzzle out the disappearances of a client’s husband and their own long-gone father, the misguided energy of their surveillance skews the picture:

“I did feel partly responsible for whatever it was that had happened to her husband,” says the more sensible sister, “as though our mere presence had set something in motion that might have remained dormant otherwise.”

“Opa-Locka” begins amid the familiar tropes of a stakeout, but from the sisters’ flawed investigation van den Berg tells an entirely different story, one of secrets, risk, loss, and “two little girls who tried to make something out of nothing.” Such is the legerdemain of The Isle of Youth – which itself is both an ideal of new beginnings and also some shabby tourist trap off the coast of Cuba. There are few tidy resolutions between these alternate versions, though that shouldn’t come as any surprise: one of basic tenets of The Eisenberg Uncertainty Principle is that things don’t get any easier, they only get different.

Recovery in Pieces: A Study of the Literature of 9/11

Actually, I am sitting here in my pants, looking at a blank screen, finding nothing funny, scared out of my mind like everybody else, smoking a family-sized pouch of Golden Virginia.

–Zadie Smith, "This is how it feels to me," in The Guardian, October 13, 2001.

If you want to read the Greatest Work of 9/11 Literature, the consensus is: keep waiting. It will be a long time before someone writes it.

We don’t know what it will look like. It could be the Moby Dick of the Twenty-First Century, or maybe a new Gatsby, but more likely it will be neither. Maybe it won’t be a novel at all. It could be a sweeping history (maybe) of New York at the turn of the Millennium and of America on the precipice of total economic implosion (or not). We will read it on our iPad34 (or maybe by then Amazon will beam narratives directly into our brain for $1.99). One thing that seems certain is that no one has yet written that book. Not DeLillo (too sterile), Safran Foer (too cloying), Hamid (too severe), Messud (too prissy), O’Neill (too realist), Spiegelman (too panicked), Eisenberg (too cryptic) or the 9/11 Commission (too thorough).

The idea is that it will take time to determine what — if any — single piece of literature best captures the events of September 11, 2001 and their aftermath. We can name any number of reasons why authors seem to have underwhelmed us during the past decade. Perhaps they suffered from an extended period of crippling fear of the kind Zadie Smith described just weeks after the attacks. Literary production can tend to feel superfluous in the aftermath of large loss of life. Or perhaps it’s our persistent closeness to the events. We’re still only a decade out, despite the sense that we’ve been waiting in airport security lines for an eternity. (By comparison, Heller wrote Catch-22 almost 20 years after Pearl Harbor; War and Peace wasn’t finished until 50 years after France’s invasion of Russia; and I think the jury may still be out on who wrote the definitive work on Vietnam). We can’t blame earnest authors for trying. It just wasn’t long enough ago yet.

None of this stops critics from trying to figure out the best 9/11 book so far.

We gather books about 9/11 (and some would go as far as to make the hyperbolic-somewhat-tongue-in-cheek claim “they’re all post-9/11 books now”) into a single pile and determine who has best distilled the essence of terrorism’s various traumatic effects on our national psyche and our ordinary life. On one hand, it seems plausible to blame this tic on our collective reduced attention spans and expectations for rapid literary responses to cultural and historical events. Or more simply: we want our book and we want it now. On the other hand, the imperative to produce a 9/11 book became a kind of authorly compulsion — a new way to justify the craft of writing to an audience whose numbers always seem to be inexorably marching toward zero. Amid conversations about “the death of the novel” (and we often fail to remember that these discussions were robust and ominous-sounding back in 2001 too), 9/11 provided a renewed opportunity for books to become culturally relevant. Fiction, poetry, creative nonfiction — the whole lot. Any literary rendering of the post-9/11 world would be preferable to the unmediated reality of it. Or more simply: writers could come to the rescue of a traumatized public. Or even more simply: why shouldn’t it have been writing that could have soothed us and given us some kind of answers?

Whether these considerations will eventually vindicate the authors who tried to translate 9/11 into literature just a few raw years after the fact, we can’t say. My contention is simply that, for now, they shouldn’t be so universally panned for trying. In the meantime, perhaps this decade anniversary isn’t an opportunity to determine who’s written the best book so far, but rather to reconsider accepted notions about what constitutes the Literature of 9/11 in the first place. The books we have written and read since 2001 tell us more about ourselves than about the capacity of literature to encompass the consequences of an event like these terrorist attacks. Rather than rank these books, we should fit them into categories that allow us to consider why we turn to literature in the aftermath of a traumatic event. We can more usefully ask ourselves “Why read?” and think about why this particular historical moment produced such a rapid and rapidly evolving body of literature.

Here are some ideas to help get this conversation started. I don’t intend these bullet point-style assertions to be a decisive argument. Rather, I guess I’m just trying to figure out a way to group and regroup the books that have been on our collective radar for the past ten years.

1. To understand the post-9/11 world, we should look to the literature of the last moments before September 11, 2001.

Jonathan Franzen’s The Corrections was published on September 1, 2001. Concerned with biotech, the dot-com crash, and the erosion of middle class family life in millennial America, Franzen’s novel captures a vague sense of menace in the days immediately before 9/11. And, though she has become better known for A Visit from the Goon Squad (which mentions the World Trade Center, only briefly) Jennifer Egan’s Look at Me proves that fiction can often seem to predict the world just ahead of us. The events of the novel so uncannily represent the shadow presence of terrorism in the unseen spaces of American everyday life that Egan, who wrote the book entirely before 9/11, included an afterward to the novel in 2002. She writes: “Had Look at Me been a work-in-progress last fall, I would have had to receive the novel in light of what happened. Instead, it remains an imaginative artifact of a more innocent time.” This last line has always been problematic for me. Were we really that innocent before 9/11? Authors seemed totally capable of exposing the dread underlying the exuberance (rational or otherwise) at the close of the Millennium. I wonder to whether we’ll remember the pre-9/11 years as one of innocence or willful ignorance.

2. There is no single body of 9/11 Literature.

As I have mentioned, the tendency in the past decade has been to lump together all works of fiction about 9/11. As the number of works that deal directly and indirectly with the terrorist attacks has ballooned, the moniker “9/11 Literature” has become a dull catchall term used to describe too many types of books. Instead, we can try to make some distinctions to figure out more precisely what different kinds of books have done, and stop trying to judge them all by the same criteria. It can be helpful, for example, to distinguish between 9/11 Literature and Post-9/11 Literature. Whereas Mohsin Hamid’s The Reluctant Fundamentalist and Don DeLillo’s Falling Man pivot around the events of September 11, books like Claire Messud’s The Emperor’s Children suggest how the events and their effects can be pushed to the margins. Works of 9/11 Literature obsess about the intricate and far-reaching effects of 9/11 on the lives of characters, whereas Post-9/11 Literature emphasizes how individuals can move beyond the trauma of the attacks and allow ordinary life to resume its flow.

3. The literary response to 9/11 better helps us understand the longer-term psychological effects of terrorism on families, communities, and nations.

Art Spiegelman’s In the Shadow of No Towers and Jonathan Safran Foer’s Extremely Loud and Incredibly Close help us understand how the effects of cultural trauma reach into future generations. They explore how we are all implicated into broader narratives of belonging to national and cultural heritages. Spiegelman had to publish the serial version of his comics in Germany because squeamish newspapers in America believed that his critiques of the Bush Administration would be poorly received at home. Likewise, Safran Foer’s novel was frequently criticized as playing on themes of grief and loss that seemed too fresh. As time passes, these criticisms fall away, and what we’re left with is a more subtle understanding of how — in the immediate aftermath of a cultural trauma — we must try to recover as individuals.

4. The relationship between The 9/11 Commission Report and The 9/11 Report: A Graphic Adaptation stands as one of the most compelling pairs of books to emerge in the past ten years — and neither one of these is a novel.

While I’d argue that no single works stands out as the definitive representation of the terrorist attacks, a reader could do no better to understand the attacks of September 11, 2001 than to devour the 9/11 Commission’s official report. To 9/11 truthers, it probably makes sense that the government would produce an eloquent and sophisticated rendering of the attacks, and the complicated histories of terrorism and American intelligence failures that led to them. But to the rest of us, it comes as a fascinating surprise — one that reveals the government’s investment in the production of a literary artifact of some serious depth and skilled sentence-making. The 9/11 Commission Report defies the expectation that a government document should be stodgy and defensive. Instead, it reveals — often in a tone that breaks its own rigid impartiality and becomes downright moving — the grating human oversights of regulators and the humanity of the terrorists themselves as they bumblingly tried to find a hiding place in America.

When read alongside Sid Jacobson and Ernie Colon’s adaptation of the report, the two works become a breathtaking and genre-bending account of 9/11. Together, they are proof that an event like 9/11 can actually produce new artistic forms. The effort to describe and understand — to probe and render aesthetically — gives rise to new ways of thinking about the world. These are not novels, but they certainly rise to the level of literature, no matter how one decides to define it.

5. It’s time to start re-thinking the place of 9/11 in the landscape of American literary production.

It has become more apparent that 9/11 is moving to the background of our cultural consciousness. Its influence remains, but its effects have faded when compared to what seem like more pressing economic and political concerns. Books like Deborah Eisenberg’s Twilight of the Superheroes help us understand what this process of fading looks like. But to return to Franzen and Egan, no two books seem better suited to the moment after the post-9/11 moment than Freedom and A Visit from the Goon Squad. To understand how authors have begun to fill their blank screens with something other than images of the World Trade Center on fire, it’s hard to do better. Franzen tackles the Bush Administration while Egan projects into a future New York, in which the 9/11 memorial has become an old landmark in Lower Manhattan. Literature looks forward at the next moment — toward a space and time during which we will no longer use the term Post-9/11 to describe ourselves, if only because newer and more troubling problems will take its place.

* * *

I have left out many works and many ideas. Where are Joseph O’Neill and Ian McEwan? Where are Colum McCann and John Updike? I have left out (in the very last minute) Lorraine Adams, whose book Harbor absolutely changed the way I thought about post-9/11 America when I read it, even though it had little if anything to do with 9/11. All of this is just to say: the conversation should continue, and I think it will only get more interesting throughout the next decade.

Image credit: WarmSleepy/Flickr

The Millions Top Ten: June 2010

We spend plenty of time here on The Millions telling all of you what we’ve been reading, but we are also quite interested in hearing about what you’ve been reading. By looking at our Amazon stats, we can see what books Millions readers have been buying, and we decided it would be fun to use those stats to find out what books have been most popular with our readers in recent months. Below you’ll find our Millions Top Ten list for June.

This

Month

Last

Month

Title

On List

1.

1.

Reality Hunger

5 months

2.

5.

Stoner

6 months

3.

8.

Tinkers

2 months

4.

6.

The Big Short

4 months

5. (tie)

-

The Thousand Autumns of Jacob de Zoet

1 month

5. (tie)

-

The Girl Who Kicked the Hornet's Nest

1 month

7.

10.

Wolf Hall

6 months

8.

9.

War and Peace

3 months

9.

-

The Girl Who Played With Fire

1 month

10.

-

Out of Sheer Rage: Wrestling With D.H. Lawrence

1 month

With four books -- The Death of Ivan Ilych and Other Stories, The Mystery Guest, Let the Great World Spin, and The Interrogative Mood? -- graduating to our Hall of Fame, we have plenty of room for newcomers on our latest list. The late Stieg Larsson, whose The Girl with the Dragon Tattoo is already in our Hall of Fame, has the rest of his trilogy make the list, The Girl Who Played With Fire and the recently released The Girl Who Kicked the Hornet's Nest.

Meanwhile, David Mitchell's new novel, The Thousand Autumns of Jacob de Zoet, which was released only a few days ago, debuts tied at number five, and Geoff Dyer's 1998 bio of D.H. Lawrence, Out of Sheer Rage, which was recently championed by David Shields in these pages, debuts in the last spot on the list.

And it's Shields' controversial Reality Hunger that's still holding on to our top spot.

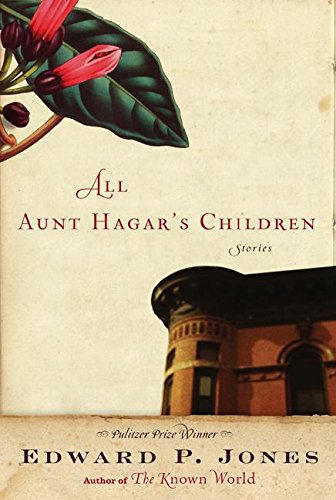

Near Misses: Twilight of the Superheroes, Although Of Course You End Up Becoming Yourself: A Road Trip with David Foster Wallace, The Known World, Then We Came to the End, The Imperfectionists

See Also: Last month's list

The Millions Top Ten: May 2010

We spend plenty of time here on The Millions telling all of you what we’ve been reading, but we are also quite interested in hearing about what you’ve been reading. By looking at our Amazon stats, we can see what books Millions readers have been buying, and we decided it would be fun to use those stats to find out what books have been most popular with our readers in recent months. Below you’ll find our Millions Top Ten list for May.

This

Month

Last

Month

Title

On List

1.

3.

Reality Hunger

4 months

2.

2.

The Death of Ivan Ilyich and Other Stories

6 months

3.

4.

Let the Great World Spin

6 months

4.

5.

The Mystery Guest

6 months

5.

6.

Stoner

5 months

6.

8.

The Big Short

3 months

7.

9.

The Interrogative Mood

6 months

8.

-

Tinkers

1 month

9.

10.

War and Peace

2 months

10.

7.

Wolf Hall

5 months

This month, David Shields' controversial Reality Hunger slips into the top spot. Shields recently offered an energetic defense of the book and an accompanying reading list.

Graduating to our Hall of Fame this month is Jonathan Franzen's The Corrections, which appeared at the top of our panel's list and number eight on our readers' list in our "Best of the Millennium (So Far)" series last year. We've been learning more about Franzen's next novel, Freedom, out later this year.

Our only debut this month is the surprise Pulitzer winner and small press hero, Tinkers by Paul Harding.

Near Misses: The Girl Who Kicked the Hornet's Nest, Although Of Course You End Up Becoming Yourself: A Road Trip with David Foster Wallace, The Known World, Twilight of the Superheroes, Then We Came to the End

See Also: Last month's list

Reality Squared: A Profile of Deborah Eisenberg

By most external measures, Deborah Eisenberg has been on a roll lately. There are the rarefied reviews that greeted 2006's Twilight of the Superheroes ("masterful"; "masterly"; "wise, careful, benevolent"). There's the 2009 MacArthur "Genius" Grant. And, just this month, there's the publication of a 950-plus page omnibus that - like a camera pulling back from a single edifice to reveal the skyline's sweep - lays bare the scope of what she's been up to these last 30 years.

If Eisenberg's Collected Stories tell us anything, though, it's that external measures are the least interesting kind, and, reached by phone at her New York apartment, she expresses a kind of shambolic bemusement at her achievements, as though they might just as easily have accrued to some other fiction writer who shares her name. "I'm terribly inarticulate," she apologizes at one point. "Glacially slow," is how she describes her process at another.

Actually, she's frightfully quick. In conversation as on the page, she moves fluidly from the telling detail to the big idea and back again. Metaphors emerge at thoughtful intervals, like amuse-bouche at a casually brilliant restaurant. But it would be a mistake to write off Eisenberg's eloquent disavowal of her own eloquence as mere good manners. Rather, it is emblematic of the antinomies that animate her long short stories: articulate muzziness, ironic passion, controlled chaos. Together, they comprise an ethos we might call active passivity - a kind of curiosity about the things that simply seem to happen to one. That is, against the aura of willful exertion that usually clings to the word "master," The Collected Stories arise from their maker's patient attunement to the accidents of character and of art.

For Eisenberg, the first accident was to be raised in Winnetka, Illinois, a predominantly Gentile suburb 20 miles north of Chicago. Some of the Eisenhower-era temperament of the place can be glimpsed in her Reagen-era short story "The Robbery." Though there were "some deeply, deeply liberal people there," she says now, "It was very conservative in certain ways," and sharply divided from the Jewish enclaves it abutted. She was not conscious of the "anti-Semitic element" until after she left, but had a sense of being different from an early age. Outwardly a "very nice girl," she felt inwardly "like a complete Martian."

This is in some measure the fate of all sensitive and intelligent children, existing as they do in a world controlled by somewhat less sensitive and intelligent adults. (Eisenberg would soon be plucked from her public school and packed off to a boarding academy in Vermont.) But her sense of unbelonging had a political dimension that soon made itself felt. At the height of the Civil Rights Movement, she managed to get herself thrown in jail as part of a group working on a project "in a KKK county somewhere in the Smoky Mountains. . . . I can't take credit for it," she insists (a high-school friend had invited her along) but "It was probably the thing I'm most proud of in my whole life." It was what happened afterward, however, that would make the biggest impression on her art. She returned north to find the adult world eager to chalk the injustices she'd witnessed up to adolescent hyperbole. "It was an eye-opening experience: the experience of being told you didn't see what you saw."

The ultimate remedy for this estrangement lay in the city, which had always seemed "very glamorous and beautiful" to Eisenberg - a glamor more powerful for being forbidden. "'Lock your door, Jill'" says the mother in "The Robbery," as she drives her daughter in

to one of the stately old department stores, or to a matinee when the ballet came to town . . . and at that moment the earth seemed to become transparent, and they would drive toward its center, penetrating worlds and then worlds. When they reemerged on the surface, which was settled on a human scale with houses and shrubs and newly covered driveways, her mother would draw in her breath deeply, and the road would heal up behind them and become opaque. But later the hidden day would emit around Jill the troubling light of a dream.

After a stint at Marlboro College and a period of hitchhiking around the country with a boyfriend, Eisenberg ended up in New York. She was rudderless, directionless, "confused and desperate," she remembers, "in the condition of a beached whale. . . . I was always confused in those days." New York did not end that confusion so much as provide a hospitable setting for it, as it would for so many of Eisenberg's characters. "My expectations were not of a glittering life of any sort, but I loved the metropolitan tolerance, the metropolitan disorder, the feeling of something continually being generated, even if it was anarchic, and quite scary." She was comforted, too, by the anonymity the city offered. "It was like crawling into a great rumpled bed," she says approvingly. "A bed in which there are already people."

One of those people was the actor and playwright Wallace Shawn, whose life had been running on a parallel track. Having grown up even more fully ensconced in the fruits of postwar prosperity - Putney; Harvard; father the editor of The New Yorker - Shawn had grown concomitantly more uneasy about the provenance of those fruits (as he describes in his recent book, Essays). When he and Eisenberg began seeing each other, it was not only a meeting of the minds - "the wonderful writer with whom I live," is how she refers to him these days - but also the opening, albeit obscure, of a vocational path.

The first story she wrote was a diary-like thing called "Days," whose precipitating incident was the protagonist's decision to quit smoking. "My only autobiographical story," Eisenberg calls it. Though she began it many years after she herself had given up cigarettes, she was, like her protagonist, "falling apart" at the time of composition. "I was in terrible shape," she recalls, "like a heap of shredded paper on the floor. [Shawn] gave me a pen and paper and said, well you have nothing to lose." The result is, in its brilliant images, absurdist wit, and sensitivity to the slightest shifts in the inner life of its protagonist, like Svevo's Confessions of Zeno in miniature. And one senses, between the lines, a writer discovering her own powers. Late in the story, the narrator suggests that

It is amazing to be able to find out what I want to do at any given moment, out of what seems to be nothing, out of not knowing at all. It is secretly and individually thrilling, like being able to open my fist and release into the air a flock of white doves.

Another critical intervention - or happy accident, depending on one's orientation - came in the person of Joe Papp, renowned founder and director of New York's Public Theater. After a friend of Eisenberg's had directed a staged reading of "Days" at the Public, Papp asked her to write something for the theater. At first, she declined, but when he offered money, she set to work on her first and only play, Pastorale. Eisenberg's ear for dialogue, soon to be celebrated, was at that point an unknown quantity, even to herself; "Days" had contained relatively few lines of direct speech. But she felt "weirdly confident" in Pastorale, and even though Papp "ended up hating it," she might not have become a professional writer had he not first mistaken her for one.

A series of first-person stories followed, which, somewhat to their author's surprise, would become the collection Transactions in a Foreign Currency. As in "Days," the form of the dramatic monologue offered Eisenberg intimate, moment-by-moment access to the surprises and disappointments of her characters. She had a sense that she was cheating, somehow, by making all of her protagonists an "I," but feared that the linguistic plasticity that interested her wouldn't be possible otherwise. And then one day, she says, she decided that it would. She began writing her first third-person stories, which would appear in her breakout collection, Under the 82nd Airborne. "It had taken me all these years to figure it out," she says. "The stories had taken shape under water, sort of."

In the shift from first- to third-person, she had discovered a voice to match her sensibility: a voice struggling toward objective fidelity to subjectivity of lived life. It is the sound of a mind talking to itself, replete with hesitations, gaps, interjections (of course), and adverbs, which Eisenberg wields more expertly than any writer since Henry James. Expressionism and realism reveal themselves as aspects of a single phenomenon. Here, for example, is the waitress Patty, in "A Cautionary Tale," climbing into the lap of one of her customers, a transvestite dancer named Ginger (in this scene wearing theatrical wings).

Ginger brushed his cheek against Patty's lashes, and when she opened her eyes again the eyes that gleamed back were feral and slanting. "Little flower mouth," he said, and Patty's mouth opened, too, as he arched, letting her glide it from his jeweled earlobe down his polished neck and along the sweep of his collarbone, but there was a quick explosion in her brain as "Waitress! Waitress!" someone called, and Patty scrambled trembling to her feet, scraping her shoulder against papier-mâché.

The other (related) innovation of Under the 82nd Airborne was its explicit engagement with the political. Its title story is set in Honduras, which the Reagan Administration had been using to facilitate not-so-covert aid to the Nicaraguan Contras. Another story, "Holy Week" - and three in the collection that followed, All Around Atlantis - would take place in Central American landscapes scarred by three-plus decades of antidemocratic U.S. interventions. These stories arose, Eisenberg says, from her travels in the region with Shawn, which began around the time of the Iran-Contra scandal and continued through the end of the go-go '80s. Shawn, she says

was very interested to see Nicaragua, to see a socialist revolution. Of course, I didn't know a socialist from a socialite. But I wanted to see Guatemala. You know...lakes, volcanoes. Wallace asked did I know what I was talking about, and suggested I do some reading. I said I'd do it when I got back.

Then again, Eisenberg was not exactly disinterested in the subject of justice. She admits,

I did start to read about U.S. policy in the region and then wanted very much to go to Honduras. . . . The whole thing was so shattering, that to come back to the unreality that New York was was simply intolerable for a while, so we kept going back and back.

Together, Under the 82nd Airborne and All Around Atlantis work to suggest a context for the lives of privilege and disorder depicted in Eisenberg's earlier fiction. As she puts it, "Guatemala provided a way to understand what was going on in my own country, which is corporatocracy." It was a short jump from seeing U.S. military power propping up banana republics abroad to the sense of pervasive but intangible powers at home - a real world behind the unreal world, or vice versa. "Well, actually," Eisenberg corrects herself, "there are two sets of real worlds and two sets of unreal worlds. . . . There's the actual real-real, which is always in flux," and there's "the real world in the sense of the structures that form the world we live in." And then, she says, confidence growing, there's "the very unreal world that we in the U.S. live in, the parochial world of what used to be the middle class and is the educated elite now that the middle class doesn't exist anymore." And finally there's the subjunctive unreality - the personal realm of desire and wish and dream - we move through daily. This layering of worlds and the attempt to negotiate it would persist in Twilight of the Superheroes, set against the backdrop of September 11 and the War on Terror.

Of course ideas - especially political ideas, and especially one's own - pose certain risks for fiction. It is a peculiarity of Eisenberg's writing (Norman Rush may be her only peer in this) that it manages to adumbrate "the structures of the world we live in" without ever telling us what to do. A key strategy is irony, and particularly a willingness to concede that right-minded characters are often wrong and wrong-minded characters right. Take "A Cautionary Tale," for example: about which Eisenberg says, "I amused myself partly by instilling attitudes that are mine" not in Patty, the heroine, but in an "absolutely intolerable," fire-breathing liberal named Stuart. Or take "Revenge of the Dinosaurs," from 2003, whose main character, Lulu, combines glimmerings of historical awareness with utter interpersonal ineptitude. In The Collected Stories, as in the actual-real-real, people rarely manage to keep their personal and political lives consistent.

Indeed, Eisenberg points out, fiction liberates one from the burdens of consistency.

I think one of the great things about fiction is that you don't have to adhere to a formal idea about building a case. The responsibility is almost to go beyond the confines of any case you could build. And people do talk about things, of course. They don't just talk about nail polish. You can go for days thinking, "All anybody cares about anymore is square footage," and then have three extraordinary conversations in the grocery store.

It helps, she says, that her own ideas "aren't even complete. Always, they're being shaped by reality." That's actual real reality, of course, which may help to explain why the last decade (which saw "reality-based community" become an epithet) so unsettled Eisenberg's characters. "This is a very interesting moment to be alive," she says, "and that is the only thing that makes it bearable."

As for what comes next, she has "absolutely no idea. I really want to move along . . . I really do. But I'm sort of desperately throwing myself against pieces of paper and only coming up with what look like bug smears." Of course, she has felt glacially slow and terribly inarticulate in writing her first 27 stories. "But one wants to say, oh, when I complained then, I wasn't really serious. Now I'm serious. I have to reconfigure my brain somehow. . . . It hasn't quite reconfigured itself yet."

This last emendation - from the active voice to the reflexive - has come to seem like a classic Eisenberg move. It's as if a too-proprietary stance toward her own mind might endanger the flow of perceptions that shape her art. As if knowing might get in the way of seeing, and feeling. But one has every confidence that eventually active passivity, or passive activity, will win out - that her brain will have been reconfigured. And if, for all her perceptiveness, Deborah Eisenberg can't quite see what she's accomplished in all these years of hurling herself against pieces of paper - "I myself don't see any particular thing in this collection," she confesses - perhaps she doesn't need to. The actual, real reality is there, between the covers of The Collected Stories, waiting for prepared spirits to receive it.

(Photo © Diana Michener)

Bonus Links:

An excerpt from The Collected Stories

Our review of Under the 82nd Airborne

Deborah Eisenberg reads from "Revenge of the Dinosaurs"

The Millions Top Ten: April 2010

We spend plenty of time here on The Millions telling all of you what we’ve been reading, but we are also quite interested in hearing about what you’ve been reading. By looking at our Amazon stats, we can see what books Millions readers have been buying, and we decided it would be fun to use those stats to find out what books have been most popular with our readers in recent months. Below you’ll find our Millions Top Ten list for April.

This

Month

Last

Month

Title

On List

1.

1.

The Corrections

6 months

3.

3.

The Death of Ivan Ilyich and Other Stories

5 months

3.

2.

Reality Hunger

3 months

4.

4.

Let the Great World Spin

5 months

5.

10.

The Mystery Guest

5 months

6.

9.

Stoner

4 months

7.

6.

Wolf Hall

4 months

8.

5.

The Big Short

2 months

9.

7.

The Interrogative Mood

5 months

10.

-

War and Peace

1 month

Graduating to our Hall of Fame this month is W.G. Sebald's Austerlitz, which appeared on both our panel's list and our readers list in our "Best of the Millennium (So Far)" series last year. Our panel's winner in the same series, Jonathan Franzen's The Corrections, stays in the top spot. We've been looking forward to Franzen's next novel, Freedom, out later this year.

Our only debut this month is a classic. Leo Tolstoy's War and Peace landed on lots of reading lists after we published Kevin's thoughtful meditation on the book and what it means to be affected by great art.

Near Misses: Although Of Course You End Up Becoming Yourself: A Road Trip with David Foster Wallace, Asterios Polyp, The Known World, Tinkers, Solar, Twilight of the Superheroes

See Also: Last month's list

Dissecting the List: An Excursus

Of Lists, Generally

Most Emailed Articles. Most Beautiful People. 100 Best Singles. 50 Greatest Novelists Between the Ages of 31 and 33. Verily, as William H. Gass observes in his wonderful essay collection Tests of Time — which made the New York Times Notable Books List even as it missed Bestsellers by a mile — we are nowadays "obsessed by hierarchies in the form of lists."

The etiology of this obsession is elaborate enough that a list of the Top 10 causes would not begin to exhaust it. Still, near the head of such a list, as Gass suggests, would have to be "our egalitarian and plural society," which renders questions of value both vital and vexed. And somewhere nearby (just above, or below, or beside?) would be our access to a venue where the itch to list can be almost continuously scratched: the Internet. Online tools for the gathering and measuring and dissemination of data have made list-making so ridiculously easy as to be ubiquitous. Kissing listservs and bookmarks and blogrolls goodbye would be something like turning your back on the Internet altogether.

Still, for a certain kind of mind, the lists Gass is referring to — lists that not only collect objects but rank them — would seem to give rise to at least three problems (which appear here in no particular order):

They are always incomplete — either arbitrarily circumscribed or made on the basis of incomplete information. Who has time to listen to every Single of the Decade? To gawk at every Beautiful Person?