Mentioned in:

A Year in Reading: 2024

Welcome to the 20th (!) installment of The Millions' annual Year in Reading series, which gathers together some of today's most exciting writers and thinkers to share the books that shaped their year. YIR is not a collection of yearend best-of lists; think of it, perhaps, as an assemblage of annotated bibliographies. We've invited contributors to reflect on the books they read this year—an intentionally vague prompt—and encouraged them to approach the assignment however they choose.

In writing about our reading lives, as YIR contributors are asked to do, we inevitably write about our personal lives, our inner lives. This year, a number of contributors read their way through profound grief and serious illness, through new parenthood and cross-country moves. Some found escape in frothy romances, mooring in works of theology, comfort in ancient epic poetry. More than one turned to the wisdom of Ursula K. Le Guin. Many describe a book finding them just when they needed it.

Interpretations of the assignment were wonderfully varied. One contributor, a music critic, considered the musical analogs to the books she read, while another mapped her reads from this year onto constellations. Most people's reading was guided purely by pleasure, or else a desire to better understand events unfolding in their lives or larger the world. Yet others centered their reading around a certain sense of duty: this year one contributor committed to finishing the six Philip Roth novels he had yet to read, an undertaking that he likens to “eating a six-pack of paper towels.” (Lucky for us, he included in his essay his final ranking of Roth's oeuvre.)

The books that populate these essays range widely, though the most commonly noted title this year was Tony Tulathimutte’s story collection Rejection. The work of newly minted National Book Award winner Percival Everett, particularly his acclaimed novel James, was also widely read and written about. And as the genocide of Palestinians in Gaza enters its second year, many contributors sought out Isabella Hammad’s searing, clear-eyed essay Recognizing the Stranger.

Like so many endeavors in our chronically under-resourced literary community, Year in Reading is a labor of love. The Millions is a one-person editorial operation (with an invaluable assist from SEO maven Dani Fishman), and producing YIR—and witnessing the joy it brings contributors and readers alike—has been the highlight of my tenure as editor. I’m profoundly grateful for the generosity of this year’s contributors, whose names and entries will be revealed below over the next three weeks, concluding on Wednesday, December 18. Be sure to subscribe to The Millions’ free newsletter to get the week’s entries sent straight to your inbox each Friday.

—Sophia Stewart, editor

Becca Rothfeld, author of All Things Are Too Small

Carvell Wallace, author of Another Word for Love

Charlotte Shane, author of An Honest Woman

Brianna Di Monda, writer and editor

Nell Irvin Painter, author of I Just Keep Talking

Carrie Courogen, author of Miss May Does Not Exist

Ayşegül Savaş, author of The Anthropologists

Zachary Issenberg, writer

Tony Tulathimutte, author of Rejection

Ann Powers, author of Traveling: On the Path of Joni Mitchell

Lidia Yuknavitch, author of Reading the Waves

Nicholas Russell, writer and critic

Daniel Saldaña París, author of Planes Flying Over a Monster

Lili Anolik, author of Didion and Babitz

Deborah Ghim, editor

Emily Witt, author of Health and Safety

Nathan Thrall, author of A Day in the Life of Abed Salama

Lena Moses-Schmitt, author of True Mistakes

Jeremy Gordon, author of See Friendship

John Lee Clark, author of Touch the Future

Ellen Wayland-Smith, author of The Science of Last Things

Edwin Frank, publisher and author of Stranger Than Fiction

Sophia Stewart, editor of The Millions

A Year in Reading Archives: 2023, 2022, 2021, 2020, 2019, 2018, 2017, 2016, 2015, 2014, 2013, 2011, 2010, 2009, 2008, 2007, 2006, 2005

The Great Fall 2024 Book Preview

With the arrival of autumn comes a deluge of great books. Here you'll find a sampling of new and forthcoming titles that caught our eye here at The Millions, and that we think might catch yours, too. Some we’ve already perused in galley form; others we’re eager to devour based on their authors, plots, or subject matters. We hope your next fall read is among them.

—Sophia Stewart, editor

October

Season of the Swamp by Yuri Herrera, tr. Lisa Dillman [F]

What it is: An epic, speculative account of the 18 months that Benito Juárez spent in New Orleans in 1853-54, years before he became the first and only Indigenous president of Mexico.

Who it's for: Fans of speculative history; readers who appreciate the magic that swirls around any novel set in New Orleans. —Claire Kirch

The Black Utopians by Aaron Robertson [NF]

What it is: An exploration of Black Americans' pursuit and visions of utopia—both ideological and physical—that spans the Reconstruction era to the present day and combines history, memoir, and reportage.

Who it's for: Fans of Saidiya Hartman's Wayward Lives, Beautiful Experiments and Kristen R. Ghodsee's Everyday Utopia. —Sophia M. Stewart

The Third Realm by Karl Ove Knausgaard, tr. Martin Aitken [F]

What it is: The third installment in Knausgaard's Morning Star series, centered on the appearance of a mysterious new star in the skies above Norway.

Who it's for: Real Knausgaard heads only—The Wolves of Eternity and Morning Star are required reading for this one. —SMS

Brown Women Have Everything by Sayantani Dasgupta [NF]

What it is: Essays on the contradictions and complexities of life as an Indian woman in America, probing everything from hair to family to the joys of travel.

Who it's for: Readers of Durga Chew-Bose, Erika L. Sánchez, and Tajja Isen. —SMS

The Plot Against Native America by Bill Vaughn [F]

What it is: The first narrative history of Native American boarding schools— which aimed "civilize" Indigenous children by violently severing them from their culture— and their enduring, horrifying legacy.

Who it's for: Readers of Ned Blackhawk and Kathleen DuVal. —SMS

The Mighty Red by Louise Erdrich [F]

What it is: Erdrich's latest novel set in North Dakota's Red River Valley is a tale of the intertwined lives of ordinary people striving to survive and even thrive in their rural community, despite environmental upheavals, the 2008 financial crisis, and other obstacles.

Who it's for: Readers of cli-fi; fans of Linda LeGarde Grover and William Faulkner. —CK

The Position of Spoons by Deborah Levy [NF]

What it is: The second book from Levy in as many years, diverging from a recent streak of surrealist fiction with a collection of essays marked by exceptional observance and style.

Who it's for: Close lookers and the perennially curious. —John H. Maher

The Bog Wife by Kay Chronister [F]

What it's about: The Haddesley family has lived on the same West Virginia bog for centuries, making a supernatural bargain with the land—a generational blood sacrifice—in order to do so—until an uncovered secret changes everything.

Who it's for: Readers of Karen Russell and Jeff VanderMeer; anyone who has ever used the phrase "girl moss." —SMS

The Great When by Alan Moore [F]

What it's about: When an 18-year old book reseller comes across a copy of a book that shouldn’t exist, it threatens to upend not just an already post-war-torn London, but reality as we know it.

Who it's for: Anyone looking for a Sherlock Holmes-style mystery dipped in thaumaturgical psychedelia. —Daniella Fishman

The Message by Ta-Nehisi Coates [NF]

What it's about: One of our sharpest critical thinkers on social justice returns to nonfiction, nearly a decade after Between the World and Me, visiting Dakar, to contemplate enslavement and the Middle Passage; Columbia, S.C., as a backdrop for his thoughts on Jim Crow and book bans; and the Israeli-occupied West Bank, where he sees contemporary segregation in the treatment of Palestinians.

Who it’s for: Fans of James Baldwin, George Orwell, and Angela Y. Davis; readers of Nikole Hannah-Jones’s The 1619 Project and Isabel Wilkerson’s Caste, to name just a few engagements with national and racial identity. —Nathalie op de Beeck

Abortion by Jessica Valenti [NF]

What it is: Columnist and memoirist Valenti, who tracks pro-choice advocacy and attacks on the right to choose in her Substack, channels feminist rage into a guide for freedom of choice advocacy.

Who it’s for: Readers of Robin Marty’s The New Handbook for a Post-Roe America, #ShoutYourAbortion proponents, and followers of Jennifer Baumgartner’s [I Had an Abortion] project. —NodB

Gifted by Suzuki Suzumi, tr. Allison Markin Powell [F]

What it's about: A young sex worker in Tokyo's red-light district muses on her life and recounts her abusive mother's final days, in what is Suzuki's first novel to be translated into English.

Who it's for: Readers of Susan Boyt and Mieko Kanai; fans of moody, introspective fiction; anyone with a fraught relationship to their mother. —SMS

Childish Literature by Alejandro Zambra, tr. Megan McDowell [F]

What it is: A wide-ranging collection of stories, essays, and poems that explore childhood, fatherhood, and family.

Who it's for: Fans of dad lit (see: Lucas Mann's Attachments, Keith Gessen's Raising Raffi, Karl Ove Knausgaard's seasons quartet, et al). —SMS

Books Are Made Out of Books ed. Michael Lynn Crews [NF]

What it is: A mining of the archives of the late Cormac McCarthy with a focus on the famously tight-lipped author's literary influences.

Who it's for: Anyone whose commonplace book contains the words "arquebus," "cordillera," or "vinegaroon." —JHM

Slaveroad by John Edgar Wideman [F]

What it is: A blend of memoir, fiction, and history that charts the "slaveroad" that runs through American history, spanning the Atlantic slave trade to the criminal justice system, from the celebrated author of Brothers and Keepers.

Who it's for: Fans of Clint Smith and Ta-Nehisi Coates. —SMS

Linguaphile by Julie Sedivy [NF]

What it's about: Linguist Sedivy reflects on a life spent loving language—its beauty, its mystery, and the essential role it plays in human existence.

Who it's for: Amateur (or professional) linguists; fans of the podcast A Way with Words (me). —SMS

An Image of My Name Enters America by Lucy Ives [NF]

What it is: A collection of interrelated essays that connect moments from Ives's life to larger questions of history, identity, and national fantasy,

Who it's for: Fans of Ives, one of our weirdest and most wondrous living writers—duh; anyone with a passing interest in My Little Pony, Cold War–era musicals, or The Three Body Problem, all of which are mined here for great effect. —SMS

Women's Hotel by Daniel Lavery [F]

What it is: A novel set in 1960s New York City, about the adventures of the residents of a hotel providing housing for young women that is very much evocative of the real-life legendary Barbizon Hotel.

Who it's for: Readers of Mary McCarthy's The Group and Rona Jaffe's The Best of Everything. —CK

The World in Books by Kenneth C. Davis [NF]

What it is: A guide to 52 of the most influential works of nonfiction ever published, spanning works from Plato to Ida B. Wells, bell hooks to Barbara Ehrenreich, and Sun Tzu to Joan Didion.

Who it's for: Lovers of nonfiction looking to cover their canonical bases. —SMS

Blue Light Hours by Bruna Dantas Lobato [F]

What it's about: Through the emanating blue-glow of their computer screens, a mother and daughter, four-thousand miles apart, find solace and loneliness in their nightly Skype chats in this heartstring-pulling debut.

Who it's for: Someone who needs to be reminded to CALL YOUR MOTHER! —DF

Riding Like the Wind by Iris Jamahl Dunkle [NF]

What it is: The biography of Sanora Babb, a contemporary of John Steinbeck's whose field notes and interviews with Dust Bowl migrants Steinbeck relied upon to write The Grapes of Wrath.

Who it's for: Steinbeck fans and haters alike; readers of Kristin Hannah's The Four Winds and the New York Times Overlooked column; anyone interested in learning more about the Dust Bowl migrants who fled to California hoping for a better life. —CK

Innie Shadows by Olivia M. Coetzee [F]

What it is: a work of crime fiction set on the outskirts of Cape Town, where a community marred by violence seeks justice and connection; also the first novel to be translated from Kaaps, a dialect of Afrikaans that was until recently only a spoken language.

Who it's for: fans of sprawling, socioeconomically-attuned crime dramas a la The Wire. —SMS

Dorothy Parker in Hollywood by Gail Crowther [NF]

What it is: A history of the famous wit—and famous New Yorker—in her L.A. era, post–Algonquin Round Table and mid–Red Scare.

Who it's for: Owners of a stack of hopelessly dog-eared Joan Didion paperbacks. —JHM

The Myth of American Idealism by Noam Chomsky and Nathan J. Robinson [NF]

What it is: A potent critique of the ideology behind America's foreign interventions and its status as a global power, and an treatise on how the nation's hubristic pursuit of "spreading democracy" threatens not only the delicate balance of global peace, but the already-declining health of our planet.

Who it's for: Chomskyites; policy wonks and casual critics of American recklessness alike. —DF

Mysticism by Simon Critchley [NF]

What it is: A study of mysticism—defined as an experience, rather than religious practice—by the great British philosopher Critchley, who mines music, poetry, and literature along the way.

Who it's for: Readers of John Gray, Jorge Luis Borges, and Simone Weil. —SMS

Q&A by Adrian Tomine [NF]

What it is: The Japanese American creator of the Optic Nerve comic book series for D&Q, and of many a New Yorker cover, shares his personal history and his creative process in this illustrated unburdening.

Who it’s for: Readers of Tomine’s melancholic, sometimes cringey, and occasionally brutal collections of comics short stories including Summer Blonde, Shortcomings, and Killing and Dying. —NodB

Sonny Boy by Al Pacino [NF]

What it is: Al Pacino's memoir—end of description.

Who it's for: Cinephiles; anyone curious how he's gonna spin fumbling Diane Keaton. —SMS

Seeing Baya by Alice Kaplan [NF]

What it is: The first biography of the enigmatic and largely-forgotten Algerian artist Baya Mahieddine, who first enchanted midcentury Paris as a teenager.

Who it's for: Admirers of Leonora Carrington, Hilma af Klint, Frida Kahlo, and other belatedly-celebrated women painters. —SMS

Absolution by Jeff VanderMeer [F]

What it is: A surprise return to the Area X, the stretch of unforbidding and uncanny coastline in the hit Southern Reach trilogy.

Who it's for: Anyone who's heard this song and got the reference without Googling it. —JHM

The Four Horsemen by Nick Curtola [NF]

What it is: The much-anticipated cookbook from the team behind Brooklyn's hottest restaurant (which also happens to be co-owned by James Murphy of LCD Soundsystem).

Who it's for: Oenophiles; thirty-somethings who live in north Williamsburg (derogatory). —SMS

Seeing Further by Esther Kinsky, tr. Caroline Schmidt [F]

What it's about: An unnamed German woman embarks on the colossal task of reviving a cinema in a small Hungarian village.

Who it's for: Fans of Jenny Erpenbeck; anyone charmed by Cinema Paradiso (not derogatory!). —SMS

Ripcord by Nate Lippens [NF]

What it's about: A novel of class, sex, friendship, and queer intimacy, written in delicious prose and narrated by a gay man adrift in Milwaukee.

Who it's for: Fans of Brontez Purnell, Garth Greenwell, Alexander Chee, and Wayne Koestenbaum. —SMS

The Use of Photography by Annie Ernaux and Marc Marie, tr. Alison L. Strayer [NF]

What it's about: Ernaux's love affair with Marie, a journalist, while she was undergoing treatment for cancer, and their joint project to document their romance.

Who it's for: The Ernaux hive, obviously; readers of Sontag's On Photography and Janet Malcolm's Still Pictures. —SMS

Nora Ephron at the Movies by Ilana Kaplan [NF]

What it is: Kaplan revisits Nora Ephron's cinematic watersheds—Silkwood, Heartburn, When Harry Met Sally, You've Got Mail, and Sleepless in Seattle—in this illustrated book. Have these iconic stories, and Ephron’s humor, weathered more than 40 years?

Who it’s for: Film history buffs who don’t mind a heteronormative HEA; listeners of the Hot and Bothered podcast; your coastal grandma. —NodB

[millions_email]

The Philosophy of Translation by Damion Searls [NF]

What it is: A meditation on the act and art of translation by one of today's most acclaimed practitioners, best known for his translations of Fosse, Proust, et al.

Who it's for: Regular readers of Words Without Borders and Asymptote; professional and amateur literary translators alike. —SMS

Salvage by Dionne Brand

What it is: A penetrating reevaluation of the British literary canon and the tropes once shaped Brand's reading life and sense of self—and Brand’s first major work of nonfiction since her landmark A Map to the Door of No Return.

Who it's for: Readers of Christina Sharpe's Ordinary Notes and Elizabeth Hardwick's Seduction and Betrayal. —SMS

Masquerade by Mike Fu [F]

What it's about: Housesitting for an artist friend in present-day New York, Meadow Liu stumbles on a novel whose author shares his name—the first of many strange, haunting happenings that lead up to the mysterious disappearance of Meadow's friend.

Who it's for: fans of Ed Park and Alexander Chee. —SMS

November

The Beggar Student by Osamu Dazai, tr. Sam Bett [F]

What it is: A novella in the moody vein of Dazai’s acclaimed No Longer Human, following the 30-something “fictional” Dazai into another misadventure spawned from a hubristic spat with a high schooler.

Who it's for: Longtime readers of Dazai, or new fans who discovered the midcentury Japanese novelist via TikTok and the Bungo Stray Dogs anime. —DF

In Thrall by Jane DeLynn [F]

What it is: A landmark lesbian bildungsroman about 16-year-old Lynn's love affair with her English teacher, originally published in 1982.

Who it's for: Fans of Joanna Russ's On Strike Against God and Edmund White's A Boy's Own Story —SMS

Washita Love Child by Douglas Kent Miller [NF]

What it is: The story of Jesse Ed Davis, the Indigenous musician who became on of the most sought after guitarists of the late '60s and '70s, playing alongside B.B. King, Bob Dylan, John Lennon, and more.

Who it's for: readers of music history and/or Indigenous history; fans of Joy Harjo, who wrote the foreword. —SMS

Set My Heart on Fire by Izumi Suzuki, tr. Helen O'Horan [F]

What it is: Gritty, sexy, and wholly rock ’n’ roll, Suzuki’s first novel translated into English (following her story collection, Hit Parade of Tears) follows 20-year-old Izumi navigating life, love, and music in the underground scene in '70s Japan.

Who it's for: Fans of Meiko Kawakami, Ursula K. Le Guin, and Marlowe Granados's Happy Hour. —DF

Didion & Babitz by Lili Anolik [NF]

What it is: A dual portrait of Joan Didion and Eve Babitz, who are so often compared to—and pitted against—each other on the basis of their mutual Los Angeles milieu.

Who it's for: Fans or haters of either writer (the book is fairly pro-Babitz, often at Didion's expense); anyone who has the Lit Hub Didion tote bag. —SMS

The Endless Refrain by David Rowell [NF]

What it's about: How the rise of music streaming, demonitizing of artist revenue, and industry tendency toward nostalgia have laid waste to the musical landscape, and the future of music culture.

Who it's for: Fans of Kyle Chayka, Spence Kornhaber, and Lindsay Zoladz. —SMS

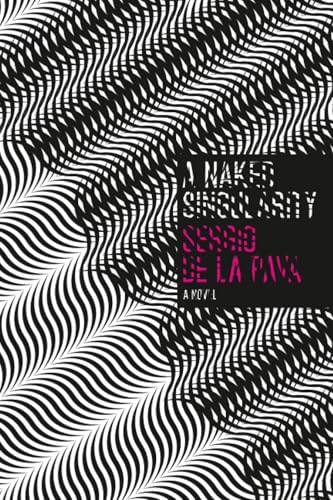

Every Arc Bends Its Radian by Sergio De La Pava [F]

What it is: A mind- and genre-bending detective story set in Cali, Colombia, that blends high-stakes suspense with rigorous philosophy.

Who it's for: Readers of Raymond Chandler, Thomas Pynchon, and Jules Verne. —SMS

Something Close to Nothing by Tom Pyun [F]

What it’s about: At the airport with his white husband Jared, awaiting a flight to Cambodia to meet the surrogate mother carrying their adoptive child-to-be, Korean American Wynn decides parenthood isn't for him, and bad behavior ensues.

Who it’s for: Pyun’s debut is calculated to cut through saccharine depictions of queer parenthood—could pair well with Torrey Peters’s Detransition, Baby. —NodB

Rosenfeld by Maya Kessler [F]

What it is: Kessler's debut—rated R for Rosenfeld—follows one Noa Simmons through the tumultuous and ultimately profound power play that is courting (and having a lot of sex with) the titular older man who soon becomes her boss.

Who it's for: Fans of Sex and the City, Raven Leilani’s Luster, and Coco Mellor’s Cleopatra and Frankenstein. —DF

Lazarus Man by Richard Price [F]

What it is: The former The Wire writer offers yet another astute chronicle of urban life, this time of an ever-changing Harlem.

Who it's for: Fans of Colson Whitehead's Crook Manifesto and Paul Murray's The Bee Sting—and, of course, The Wire. —SMS

Stranger Than Fiction by Edwin Frank [NF]

What it is: An astute curveball of a read on the development and many manifestations of the novel throughout the tumultuous 20th century.

Who it's for: Readers who look at a book's colophon before its title. —JHM

Letters to His Neighbor by Marcel Proust, tr. Lydia Davis

What it is: A collection of Proust’s tormented—and frequently hilarious—letters to his noisy neighbor which, in a diligent translation from Davis, stand the test of time.

Who it's for: Proust lovers; people who live below heavy-steppers. —DF

Context Collapse by Ryan Ruby [NF]

What it is: A self-proclaimed "poem containing a history of poetry," from ancient Greece to the Iowa Workshop, from your favorite literary critic's favorite literary critic.

Who it's for: Anyone who read and admired Ruby's titanic 2022 essay on The Waste Land; lovers of poetry looking for a challenge. —SMS

How Sondheim Can Change Your Life by Richard Schoch [NF]

What it's about: Drama professor Schoch's tribute to Stephen Sondheim and the life lessons to be gleaned from his music.

Who it's for: Sondheim heads, former theater kids, end of list. —SMS

The Serviceberry by Robin Wall Kimmerer [NF]

What it is: 2022 MacArthur fellow and botanist Kimmerer, an enrolled member of the Citizen Potawatomi Nation, (re)introduces audiences to a flowering, fruiting native plant beloved of foragers and gardeners.

Who it’s for: The restoration ecologist in your life, along with anyone who loved Braiding Sweetgrass and needs a nature-themed holiday gift. —NodB

My Heart Belongs in an Empty Big Mac Container Buried Beneath the Ocean Floor by Homeless [F]

What it is: A pseudonymous, tenderly comic novel of blue whales and Golden Arches, mental illness and recovery.

Who it's for: Anyone who finds Thomas Pynchon a bit too staid. —JHM

Yoke and Feather by Jessie van Eerden [NF]

What it's about: Van Eerden's braided essays explore the "everyday sacred" to tease out connections between ancient myth and contemporary life.

Who it's for: Readers of Courtney Zoffness's Spilt Milk and Jeanna Kadlec's Heretic. —SMS

Camp Jeff by Tova Reich [F]

What it's about: A "reeducation" center for sex pests in the Catskills, founded by one Jeffery Epstein (no, not that one), where the dual phenomena of #MeToo and therapyspeak collide.

Who it's for: Fans of Philip Roth and Nathan Englander; cancel culture skeptics. —SMS

Selected Amazon Reviews by Kevin Killian [NF]

What it is: A collection of 16 years of Killian’s funniest, wittiest, and most poetic Amazon reviews, the sheer number of which helped him earn the rarefied “Top 100” and “Hall of Fame” status on the site.

Who it's for: Fans of Wayne Koestenbaum and Dodie Bellamy, who wrote introduction and afterword, respectively; people who actually leave Amazon reviews. —DF

Cher by Cher [NF]

What it is: The first in a two-volume memoir, telling the story of Cher's early life and ascendent career as only she can tell it.

Who it's for: Anyone looking to fill the My Name Is Barbra–sized hole in their heart, or looking for something to tide them over until the Liza memoir drops. —SMS

The City and Its Uncertain Walls by Haruki Murakami, tr. Philip Gabriel [F]

What it is: Murakami’s first novel in over six years returns to the high-walled city from his 1985 story "Hard-Boiled Wonderland and the End of the World" with one man's search for his lost love—and, simultaneously, an ode to libraries and literature itself.

Who it's for: Murakami fans who have long awaited his return to fiction. —DF

American Bulk by Emily Mester [NF]

What it's about: Reflecting on what it means to "live life to the fullest," Mester explores the cultural and personal impacts of America’s culture of overconsumption, from Costco hauls to hoarding to diet culture—oh my!

Who it's for: Lovers of sustainability; haters of excess; skeptics of the title essay of Becca Rothfeld's All Things Are Too Small. —DF

The Icon and the Idealist by Stephanie Gorton [NF]

What it is: A compelling look at the rivalry between Margaret Sanger, of Planned Parenthood fame, and Mary Ware Dennett, who each held radically different visions for the future of birth control.

Who it's for: Readers of Amy Sohn's The Man Who Hated Women and Katherine Turk's The Women of NOW; anyone interested in the history of reproductive rights. —SMS

December

Rental House by Weike Wang [F]

What it's about: Married college sweethearts invite their drastically different families on a Cape Code vacation, raising questions about marriage, intimacy, and kinship.

Who it's for: Fans of Wang's trademark wit and sly humor (see: Joan Is Okay and Chemistry); anyone with an in-law problem.

Woo Woo by Ella Baxter [F]

What it's about: A neurotic conceptual artist loses her shit in the months leading up to an exhibition that she hopes will be her big breakout, poking fun at the tropes of the "art monster" and the "woman of the verge" in one fell, stylish swoop.

Who it's for: Readers of Sheena Patel's I'm a Fan and Chris Kraus's I Love Dick; any woman who is grateful to but now also sort of begrudges Jenny Offil for introducing "art monster" into the lexicon (me). —SMS

Berlin Atomized by Julia Kornberg, tr. Jack Rockwell and Julia Kornberg [F]

What it's about: Spanning 2001 to 2034, three Jewish and downwardly mobile siblings come of age in various corners of the world against the backdrop of global crisis.

Who it's for: Fans of Catherine Lacey's Biography of X and Joshua Cohen's The Netanyahus. —SMS

Sand-Catcher by Omar Khalifah, tr. Barbara Romaine [F]

What it is: A suspenseful, dark satire of memory and nation, in which four young Palestinian journalists at a Jordanian newspaper are assigned to interview an elderly witness to the Nakba, the violent 1948 expulsion of native Palestinians from Israel—but to their surprise, the survivor doesn’t want to rehash his trauma for the media.

Who it’s for: Anyone looking insight—tinged with grim humor—into the years leading up to the present political crisis in the Middle East and the decades-long goal of Palestinian autonomy. —NodB

The Shutouts by Gabrielle Korn [F]

What it's about: In the dystopian future, mysteriously connected women fight to survive on the margins of society amid worsening climate collapse.

Who it's for: Fans of Korn's Yours for the Taking, which takes place in the same universe; readers of Becky Chambers and queer-inflected sci-fi. —SMS

What in Me Is Dark by Orlando Reade [NF]

What it's about: The enduring, evolving influence of Milton's Paradise Lost on political history—and particularly on the work of 12 revolutionary readers, including Malcom X and Hannah Arendt.

Who it's for: English majors and fans of Ryan Ruby and Sarah Bakewell—but I repeat myself. —SMS

The Afterlife Is Letting Go by Brandon Shimoda [NF]

What it's about: Shimoda researches the mass incarceration of Japanese Americans during WWII, and speaks with descendants of those imprisoned, for this essay collection about the “afterlife” of cruelty and xenophobia in the U.S.

Who it’s for: Anyone to ever visit a monument, museum, or designated site of hallowed ground where traumatic events have taken place. —NodB

No Place to Bury the Dead by Karina Sainz Borgo, tr. Elizabeth Bryer [F]

What it's about: When Angustias Romero loses both her children while fleeing a mysterious disease in her unnamed Latin American country, she finds herself in a surreal, purgatorial borderland where she's soon caught in a power struggle.

Who it's for: Fans of Maríana Enriquez and Mohsin Hamid. —SMS

The Rest Is Silence by Augusto Monterroso, tr. Aaron Kerner [F]

What it is: The author of some of the shortest, and tightest, stories in Latin American literature goes long with a metafictional skewering of literary criticism in his only novel.

Who it's for: Anyone who prefers the term "palm-of-the-hand stories" to "flash fiction." —JHM

Tali Girls by Siamak Herawi, tr. Sara Khalili [F]

What it is: An intimate, harrowing, and vital look at the lives of girls and women in an Afghan mountain village under Taliban rule, based on true stories.

Who it's for: Readers of Nadia Hashimi, Akwaeke Emezi, and Maria Stepanova. —SMS

Sun City by Tove Jansson, tr. Thomas Teal [F]

What it's about: During her travels through the U.S. in the 1970s, Jansson became interested in the retirement home as a peculiarly American institution—here, she imagines the tightly knit community within one of them.

Who it's for: Fans of Jansson's other fiction for adults, much of which explores the lives of elderly folks; anyone who watched that documentary about The Villages in Florida. —SMS

Editor's note: We're always looking to make our seasonal book previews more useful to the readers, writers, and critics they're meant to serve. Got an idea for how we can improve our coverage? Tell me about it at sophia@themillions.com.

[millions_email]

A Reader’s Diary: On Alan Moore’s ‘Jerusalem’

“This will be very hard for you.”

-- Alan Moore, Jerusalem (spoken by an angel)

Day 1.

Jerusalem, the new novel by Alan Moore, sits on my desk, thick and foreboding. At 1,279 pages, it’s a behemoth compared to the author’s last prose work, Voice of the Fire, a relatively scant 304.

One doesn’t just dive into a novel this size without testing the water. So I hold the book in my hands (it’s heavy, as expected, like a dense loaf of bread). I flip through the pages (the resultant breeze feels nice on this soupy summer day). I read over the marketing copy (vague, as expected). I think back on other Alan Moore works I’ve enjoyed (Watchmen, of course, but also his true magnum opus, the Jack the Ripper study From Hell). I wonder why I’ve taken up the task of reading this novel when my shelves are a graveyard of similarly sized ones, finished (Thomas Pynchon's Against the Day) and unfinished (David Foster Wallace's Infinite Jest) alike.

I think: Alan Moore’s an imaginative storyteller. Despite Jerusalem's intimidating size, it should be fun.

I also think: Maybe I should be reading this book on a Kindle.

Day 2.

There’s no clear way to approach Jerusalem other than to plunge in, so I do.

I’m a little over 200 pages in and already getting a sense of how Jerusalem is less a “mere” novel and more a grand literary project: an ambitious attempt by Moore to encapsulate the soul of his hometown of Northampton, England. The city was the same setting for his first novel, in which its spirit was captured by polyphonic voices speaking to us from 4000 B.C. to the end of the 20th century.

So far, Jerusalem is a novel the conceit of which (chapters told from different characters’ perspectives at different historical moments in different literary styles) has more strength than the story. I’m briefly introduced to Mick and Alma Warren, modern-day sibling residents of Northampton on whom the rest of the novel’s events (both past and present) supposedly hinges. I’m more excited to be thrown back into the past in chapters the disparate subjects of which seek to cast Northampton as the omphalos of England; the nexus of existence in which can be gleaned the entire story of humanity.

This is an obvious Joycean undertaking, and it goes a long way toward explaining (and perhaps justifying) Jerusalem's generous length. Moore’s writing is nothing if not hyper-descriptive; baroque, even. One wonders if this is compensation for the lack of visuals that accompany his similarly grand, tangled comic book narratives. These early chapters cross the point into self-indulgence. But just as I’m about to give up, Moore casts me into a different time frame and I’m enthralled.

One moment, I’m peering over the shoulder of a fresco restoration artist in St. Paul’s cathedral hallucinating (or not) a conversation with an angel. The next, I’m following a drug-addled sex worker walking Northampton’s streets in 2006. If there’s one thing uniting his characters here, it’s their station as members of the working class. They live and work in The Burroughs, Northampton’s lower-class area and the site of frequent tension with the forces of redevelopment.

Is there some kind of equitable justice above these streets? Some cosmic force that can set things right? Knowing Moore’s work, I’m sure these questions will have not just metaphoric answers, but literal ones as well.

Day 6.

I decided not to bring Jerusalem with me on a three-day vacation. So now I’m back at home and hunkered down in Alan Moore’s Northampton. My new goal: read around 150 pages a day.

I carry Jerusalem with me everywhere. I take the novel on public transportation to and from work, where it sits open in my lap like an infant. I try to read it on the elliptical machine at the gym, an awkward task that means I’m switching to a reclining stationary bike for the next week or so. I dip into the novel during my lunch break, after dinner, before bed.

This is heavy reading in more ways than one. The density of Moore’s prose forces me to constantly come up for air. And yet, I’m never tempted to stay above water for long. I’m intrigued by the characters: a Benedictine monk making a spiritual stop in medieval “Hamtun;” “Black Charley,” an American transplant and one of Northampton’s first black residents; the struggling modern-day poet Benedict Perrit, doing what all us struggling writers do best (namely, beg friends for drinking money).

Some characters, like the aforementioned poet, we follow from the moment they wake up to the moment they return to bed at close of day. Moore pays particular attention to mapping the city streets his characters wander. I’m reminded of a similar scene in From Hell, where Dr. William Gull’s calculated perambulations past London landmarks ultimately reveal the shape of a pentagram. I’m also reminded of W.G. Sebald, whose semi-fictional wanderers uncover the psychogeography of particular places; the secret histories trapped in landscapes and buildings.

There is true world-building going on here. Whitmanesque, these pages contain multitudes. And I’m starting to realize these disparate voices aren’t that disparate at all; in fact, they’re delicately interconnected. Figures from the past and the present, alive and dead, bob and weave and brush up against one another.

This book, I’m learning, is haunted by history.

Day 7.

One of the most striking things of Moore’s best work over the years: his focus on the nature of space-time; of time as a fourth dimension; of past, present, and future all happening at once. Time, in his Weltanschauung, is an architectural dimension that can be mapped and explored. It’s the same philosophy that haunts Dr. Manhattan in Watchmen and that propels Jack the Ripper’s legacy through time in From Hell.

Jerusalem is a startling expansion on these ideas. While ideas of space-time have appeared in nearly every chapter so far, they’re concentrated in one marvelous section I’ve just finished. Snowy, a member of the Vernall clan (of whom the siblings Mick and Alma Warren are present-day descendants), hangs off the top of a building while below, in the gutter, his wife gives birth to a daughter. During this moment of suspended time, Snowy explores the idea of the world as an “eternal city” -- one in which everything has been preordained.

There’s something frightening (and oddly comforting) about this philosophy, which borrows from the poet and mystic William Blake (an influence on Moore’s work), Friedrich Nietzsche's myth of “eternal recurrence,” and the ideas of like-minded thinkers. We’re meant to see this idea as not a curse but a kind of hope.

If it’s true, it means, in a sense, I’ll be reading this book forever.

Day 8.

I’m now over 400 pages in, and I’ve just discovered that Jerusalem is also available in a three-volume slipcase edition. My wrists ache.

While the economy of reading an enormous book in more manageable, digestible “books” are a comfort (see a similar edition for Roberto Bolaño's 2666), I’ve convinced myself that by reading Jerusalem in its uninterrupted, single-bound version, I’m getting the more authentic reading experience.

The 2016 Olympics are on in the background. Indeed, there’s something Olympian about reading Jerusalem as one entire text. I feel strong.

I’m also glad I’ve opted out of reading Moore’s novel on an e-reader. I’d most likely miss out on the physical sense of accomplishment that comes from feeling the weight of this book gradually increase in my left palm and decrease in my right: one page, then 10 pages, then 50 pages.

Day 9.

The second hefty part of Jerusalem finally lays bare the vast supernatural cosmology Moore’s hinted at in previous pages, with all their angelic visions and ghostly hauntings. What he’s created: a three-tiered universe of Northampton: the Burroughs (in our everyday reality), Mansoul (a sort of astral plane from which all time and space can be seen, the name borrowed from John Bunyan), and a mysterious Third Burrough.

For more than 300 pages, we follow Mick Warren on an odyssey through this landscape, the result of a near-death experience as a child in 1959. During the few moments where Mick’s body loses consciousness, we travel in and around this “world above a world.” We meet angels (known as “builders”). We meet demons (former “builders”). We meet a ragtag gang of ghost children called The Dead Dead Gang, some of whose members can literally dig through time. We’re flung back to seminal moments in Northampton’s history, spending the night with Oliver Cromwell on the eve of a decisive battle in the English Civil War and watching two fire demons, salamanders, cavort through the city and bring about the Great Fire of 1675.

There are some indelible images in these pages, including the ghost of a suicide bomber who’s eternally trapped in mid-explosion (the rules of this afterlife being that the form you occupy is the form you had during your greatest moment of joy) and a serpentine ghoul that haunts the River Nene and plucks newly dead souls into her underwater purgatory.

Day 12.

It’s unfair to expect perfection from mammoth books. Yet the longer a novel runs, the more unforgiving a reader becomes about moments in the story that could be tightened, or excised altogether. Great Big Novels bring out the editor inside us all.

I’ve spent three days trapped, so to speak, in the otherworldly realm of Mansoul. I’m starting to long for the voices of the humans back on three-dimensional Earth. Moore’s too talented a writer to waste his time (and ours) with much of this rambling middle section. You’ll get an important episode told from one perspective, then a shift in perspective in the next chapter that requires a recap of earlier events. This means pages go by before the narrative moves forward.

Twelve days after starting this book (holding at bay, for the moment, the deluge of other reading materials in my life), I round the halfway point of Jerusalem. It’s the moment where the spine finally cracks and I can read the book on a desk without the use of my hands.

I like to think I crack the spine out of necessity, not vindictiveness.

Day 14.

Moore, you sadist.

I’m back on the human plane of existence, back in the polyphony of voices that is Jerusalem's strength. And then, on page 900, I’m dropped into a 48-page narrative from the perspective of James Joyce’s mentally ill daughter, Lucia, a patient at Northampton’s St. Andrew’s Hospital.

These pages are written in a mock-Finnegans Wake word salad built on puns and double meanings. It feels a little sadistic, placing such a passage here. It’s an inventive idea that’s fun at first, but, like a lot in this novel, it goes on for longer than it should. Also: I’m frustrated at being impeded so close to the end by having to sort through this linguistic playground.

So here is where I make a confession. I skimmed. With a copy of the original Finnegans Wake looming over me on my bookshelf (similarly unfinished), I quickly stopped trying to parse the logic of each sentence. As soon as I got the idea -- al fresco assignations with men who may not really be there, painful memories of childhood abuse -- I moved on.

Perhaps one day this section will be worth revising and translating. As of now, I’m rabid for Jerusalem to end.

Day 15.

Moore, you genius.

A few chapters after my troubled date with Lucia Joyce, I come across one of the more brilliant, transcendent sections in the novel. It’s composed of a pivotal character’s final earthly moments interspersed with a fantastical journey in which his essence (along with that of his deceased granddaughter) travels into the future. Together, the pair witness the evolution of the human race, its eventual demise, the resurgence of giant crabs and land-walking whales as the new lords of the earth, the heat death of the universe, and the last spark of light before eternal darkness.

It’s a lovely, touching moment that rewards my investment in this novel. Arriving on the heels of a farcical play (featuring the ghosts of Samuel Beckett, Thomas Becket, John Bunyan, and John Clare), it’s a testament to Moore’s skill at genre juggling, at cultivating a sense of awe at the universe’s frightening expanse and its beautiful mysteries.

Day 16.

Sixteen days later, making the final lap of a noir-ish detective story, a poem from the perspective of a drug-addled and ghost-haunted runaway, and a somewhat anti-climactic gallery opening, I arrive at the last page.

I close Jerusalem and drop it on the floor at my feet. I don’t need to do this; it’s a purely dramatic gesture. The resultant thud is a satisfying testament to my accomplishment.

I’m drained. But I’m also grateful. And a little sad.

It’s a paradoxical feeling I get after finishing big books like this one. The quiet thrill of having been completely submerged in an author’s vision. The feeling of finally coming up for a merciful breath of air. The longing to read flash fiction by Lydia Davis.

I’m still thinking about this fascinating mess of a book and its countless allusions (both major and minor): the art of William Blake, episodes of the U.K. version of Shameless, comic books, modern art and poetry, the time theories of Charles Howard Hinton and Albert Einstein, the hymns of John Newton, demons from apocryphal books of the Bible, H.P. Lovecraft, Melinda Gebbie (Moore’s wife), Tony Blair, Jack the Ripper, Buffalo Bill, billiards, global warming, the Crusades, the War in Iraq, the end of the world. A cacophony of material that doesn’t always coalesce perfectly but that, fittingly, creates what one character describes as “an apocalyptic narrative that speaks the language of the poor.” And the mad. And the sad. And the frustrated, the lonely, the lost.

In a sense, all of us.

Day 17.

My wrists stop aching.

Like Father, Like Son: Literary Parentage in Reif Larsen’s ‘I Am Radar’

Reif Larsen’s first novel The Selected Works of T.S. Spivet was a frustrating narrative wrapped in a beautiful work of art. Parts of it, story-wise, worked wonderfully, but many sections dragged ponderously along, and then the confounding and ill-fitting finale was rushed, as if impatient to be over. But the imagination of the novel –– the lovely images annotating the text, T.S. himself –– is undeniable, as is the talent of its author. But one can always forgive a debut novel its ambition, so it was with much interest that I embarked upon Larsen’s second effort, I Am Radar, a measurably better novel than T.S. Spivet, both for its leanness and its grandness. It’s an epic page-turner filled with small, tender moments of wonder, beginning with its almost archetypally postmodern opening:

It was just after midnight in birthing room 4C and Dr. Sherman, the mustached obstetrician presiding over the delivery, was sweating slightly into his cotton underwear, holding out his hands like a beggar, ready to receive the imminent cranium.

Without warning, the room plunged into total darkness.

The “imminent cranium” belongs to Radar Radmanovic, the center, if not exactly the protagonist, of this tale, and when the lights come back on in the delivery room, Radar comes out a pitch black baby -- was it the electrical event somehow? -- with white parents. It’s 1975 in New Jersey and rumors spread, leading Radar’s mother, Charlene, to find every doctor she can to figure what happened to her son. Soon, the family lands in Norway so that Radar can undergo an experimental procedure involving a machine called a vircator, which can emit a large electromagnetic pulse and somehow rid Radar of his skin abnormality. It works, Radar’s skin lightens until it becomes “a slightly yellowish, flushed cream color,” but it also causes Radar to suffer epileptic seizures. The procedure is overseen by a group of artists/activists/puppeteers called Kirkenesferda, who are, as a group, the real protagonist of I Am Radar. After the first section, we’re launched into various histories surrounding Kirkenesferda. First we learn of the group’s master puppeteer, Miroslav Danilovic and his father, Danilo, both caught in the precursors to the Bosnian War. Miro’s creations seem impossible, puppets with no puppeteer. We get the history of a man named Raksmey Raksmey who, as a baby, was found floating on Cambodia’s Mekong River in a basket. There is also a man in the Congo who is attempting to collect every book in the world. And finally there is Kermin, Radar’s father, who may have inadvertently caused a giant rolling blackout in New Jersey.

If this all sounds eerily Pynchonian to you, that’s because it is. Deliberately. Charlene, Radar’s mother, is described reading The Crying of Lot 49, feeling “overcome with what we are able to accomplish with the simple constellation of words.” The phrase “gravity’s rainbow” appears. One sequence features the mysterious Tunguska Event from 1908, when, in the words of one character:

There was a huge explosion in Siberia. It blew out two thousand square meters of forest, something like this. Eighty million trees destroyed. Center of explosion was seventy kilometers from Vanavara, but people there, they still feel heat blast all across their skin. The shockwave broke windows, collapsed woodsheds. It blew men right off their horse. It was powerful, so powerful. Stronger than an atom bomb.

This perfectly Pynchonian (and perfectly true) historical event was also explored in Thomas Pynchon’s unjustly dismissed masterwork Against the Day, the novel to which I Am Radar is most closely aligned, in my eyes. But Larsen is doing more than simply riffing on one of his favorite author’s themes –– rather, he is riffing on many of his favorite authors' themes. One can, while reading, pick up references to Herman Melville, Leo Tolstoy, Charles Dickens, and Nikolai Gogol (Akaky Akakievich, the protagonist from one of my very favorite short stories, “The Overcoat,” show ups) and you can sense –– in the structure, in the prose, in the language –– the influence of Salman Rushdie, Jorge Luis Borges, David Foster Wallace, Mark Z.Danielewski, and, of course, Pynchon. This is a novel steeped in its own influences.

Additionally, within this 653-page tome are fictional books, like, for instance, a book on the history of Kirkenesferda, which the narrator references throughout (replete with excerpts, images, and footnotes), and a novella on part of the life of Raksmey Raksmey. There is also Radar’s book, which, within the novel’s world, he hasn’t written yet. Is I Am Radar the book Radar will write? Well, yes and no. See, on page 621, there is an image taken, a note tells us, from “Radmanovic, R. (2013) I Am Radar, p. 621,” which would suggest that, indeed, the book we’re holding in our hands is this same book. Yet, just a little later, on page 641, another image credit refers to page 705. Radar, we are to assume, wrote his own version that extends beyond the story here and that we won’t get to read.

So real books and fake books –– but what’s the point? Why engage in such esoteric literary pastiche? The short answer is that, like Radar and the other sons here, Larsen wants to declare himself.

The primary emotional thread of I Am Radar is fathers and sons, of familial legacy and individual identity. Kermin and Radar. Miro and Danilo. Raksmey and his adopted father Jean-Baptiste de Broglie. Each son struggles with becoming their own person while still acknowledging (sometimes begrudgingly) their forebears. They are like their fathers, but they are different. Like father, like son...sort of.

Larsen makes a clear connection between these literal fathers and sons and literary fathers and sons. Near the end of the book, as Radar and companions head up the Congo toward a massive secret library created by the man hoping to collect all the world’s books, an almost Biblical passage appears. It lasts nearly two pages, and comes in the form of a speech by Professor Funes, the ambitious collector who also happens to have “perfect and complete memory.” Because he can remember everything in great detail, he’s able to list all of the authors he read throughout his life. Here is a short excerpt:

I read Defoe and Asturias and Sterne and Stendhal and Verga and Carducci and Blasco Ibáñez and Hugo and Verne and Balzac and Stendhal and Flaubert and Baudelaire and Sand and Verlaine and Paz and Maupassant and Ibsen and Wordsworth and Austen and Coleridge and Shelley and Keats and Blake and Scott and Carpentier and García Márquez and Puig and Cortázar and García Lorca.

And so on, until it more or less moves it way up to “DeLillo and Mailer and Salinger.” This is like a personal version of Genesis or Chronicles with all those endless begats. Larsen, as the finale shows, acknowledges the great authors who came before him, how their influence on him is undeniable, unavoidable, deep –– but that he is still his own writer, one with formidable gifts and looming ambition.

If not everything quite works in I Am Radar –– like, e.g., characters’ names sometimes change and are hard to keep track of, which lessens the emotional impact of some of their arcs; and sometimes it’s difficult to tell if we’re reading an omniscient narrator or borrowed information from one of the fictional books or some hybrid of the two –– it’s partly due to Larsen’s maximalist approach. How can any writer sustain perfection in such a large undertaking? It’s nearly impossible to do. Anna Karenina has parts that lag, that underwhelm (most notably Levin’s long diatribes on his serfs), as does Ulysses and The Brothers Karamozov and Infinite Jest. Novels like I Am Radar, which would technically fall under the “historiographic metafiction,” are especially prone to unwieldy excess and inscrutability. Pynchon’s books fall into that same category, and his novels are unquestionably flawed. And here is Larsen, continuing the legacy, in the same vein but in his own way. Like father, like son. Sort of.

The Art of the Epigraph

1.

I don't know what I'm preparing for. My whole life I've considered valuable certain experiences, accomplishments, and knowledge simply because I imagine they'll be useful to me in the future. I'm beginning to doubt this proposition.

Here's an example. For the last ten years, I've kept a Word document for quotes. Any time I come across a worthy passage, I file it away. By now, the file has grown to over 30,000 words from hundreds of books, articles, poems, and plays. I do this not in the interest of collecting quotable prose or for the benefit of inspiration or encouragement or even insight. What I'm looking for are potential epigraphs.

You see, I love epigraphs. Everything about them. I love the white space surrounding the words. I love the centered text, the dash of the attribution. I love the promise. When I was a kid, they intimidated me with their suggested erudition. I wanted to be the type of person able to quote Shakespeare or Milton or, hell, Stephen King appropriately. I wanted to be the type of writer who understood their own work so well that they could pair it with an apt selection from another writer's work.

If I ever wrote a novel, I told myself, about a writer, maybe I could quote Barbara Kingsolver: "A writer’s occupational hazard: I think of eavesdropping as minding my own business.” Or maybe one of Philip Roth's many memorable passages on the writer's life, like:

No, one’s story isn’t a skin to be shed — it’s inescapable, one’s body and blood. You go on pumping it out till you die, the story veined with the themes of your life, the ever-recurring story that’s at once your invention and the invention of you.

Or, taking a different tack:

It may look to outsiders like the life of freedom — not on a schedule, in command of yourself, singled out for glory, the choice apparently to write about anything. But once one’s writing, it’s all limits. Bound to a subject. Bound to make sense of it. Bound to make a book of it. If you want to be reminded of your limitations virtually every minute, there’s no better occupation to choose. Your memory, your diction, your intelligence, your sympathies, your observations, your sensations, your understanding — never enough. You find out more about what’s missing in you than you really ought to know. All of you an enclosure you keep trying to break out of. And all the obligations more ferocious for being self-imposed.

In some cases, I'd read something that was so eloquent and succinct, so insightful, I'd be inspired to write something around it, even if I didn't have anything to go on other than the quote. Aleksander Hemon's The Lazarus Project is positively riddled with possible epigraphs. Right away, on page two, we get this: "All the lives I could live, all the people I will never know, never will be, they are everywhere. That is all that the world is.” (Recognize that one? If you do, that's because it has already been used as an epigraph for Colum McCann's Let the Great World Spin, except McCann changes all of the I's to we's.) Then, on the very next page, this: "There has been life before this. Home is where somebody notices when you are no longer there.” A few pages later: "I am just like everybody else, Isador always says, because there is nobody like me in the whole world.” On page 106: "Nobody can control resemblances, any more than you can control echoes." That one made me want to write about a despotic father and the son who's trying to avoid following in his footsteps. I didn't have a great need to write that story, but the quote would have fit it so perfectly I actually have an unfinished draft somewhere in my discarded Word documents.

This is, of course, a stupid way to go about crafting fiction. I learned that lesson. You can't write something simply because you've found the perfect epigraph, the perfect title, the perfect premise –– there has to be a greater need, a desire that you can't stymie. Charles Baxter once wrote, "Art that is overcontrolled by its meaning may start to go a bit dead." The same is true of art overcontrolled by anything other than the inexplicable urge to put story to paper. I know this now.

Yet I still collect possible epigraphs. And so far, I have yet to use a single entry from my document at the beginning of a piece of fiction.

2.

Epigraphs, despite what my young mind believed, are more than mere pontification. Writers don't use them to boast. They are less like some wine and entrée pairing and more like the first lesson in a long class. Writers must teach a reader how to read their book. They must instruct the tone, the pace, the ostensible project of a given work. An epigraph is an opportunity to situate a novel, a story, or an essay, and, more importantly, to orient the reader to the book's intentions.

To demonstrate the multiple uses of the epigraph, I'd like to discuss a few salient examples. But I'm going to shy away from the classic epigraphs we all know, those of Hemingway, Tolstoy, etc., the kinds regularly found in lists with titles like "The 15 Greatest Epigraphs of All Time," and talk about some recent books, since those are the ones that have excited (and, in some cases, confounded) me enough to write about the subject in the first place.

A good epigraph establishes the theme, but when it works best it does more than this. A theme can be represented in an infinity of ways, so it is the particular selection of quotation that should do the most work. Philip Roth's Indignation opens with this section of E.E. Cummings's "i sing of Olaf glad and big":

Olaf (upon what were once knees)

does almost ceaselessly repeat

"there is some shit I will not eat"

For a book titled Indignation, this seems a perfect tone with which to begin the novel. Olaf's a heroic figure, who suffered unrelenting torture and still refused to kill for any reason, which means Roth here is also elevating the narrative of his angry protagonist to heroic status. Marcus Messner is a straight-laced boy in the early 1950s, attending college in rural Ohio. Despite his best efforts, Marcus gets caught up in the moral hypocrisy of American values, winding up getting killed in the Korean War. Marcus and Olaf are, as Cummings wrote, "more brave than me:more blond than you."

Authors do this kind of thing all the time. They borrow more than just the quoted lines. In Roth's case, it was Cummings's moral outrage about American war he wanted aligned with his novel.

In Jennifer Egan's Pulitzer Prize-winning A Visit from the Goon Squad, she opens with two separate passages from Proust's In Search of Lost Time:

Poets claim that we recapture for a moment the self that we were long ago when we enter some house or garden in which we used to live in our youth. But these are most hazardous pilgrimages, which end as often in disappointment as in success. It is in ourselves that we should rather seek to find those fixed places, contemporaneous with different years.

The unknown element in the lives of other people is like that of nature, which each fresh scientific discovery merely reduces but does not abolish.

The theme of Egan's novel is time and its effects on us –– how we survive or endure, how we perish, how things change, etc. –– a fact established here by quoting the foremost authority on fictive examinations of time, memory, and life gone by. But more than that, Egan is connecting her novel –– which is full of formal daring and partly takes place in the future –– to a canonical author whose own experimentation has now become standard. Like the music industry in her book, the world of literature has changed, maybe not for the worse but irrevocably nonetheless, and Proust's monumental achievement has become, to most modern readers, an impenetrable and uninteresting work. Egan's choice of epigraph places her squarely in the same tradition. The Modernism of Proust gave way to the Postmodernism of Egan. Years on, to readers not yet born, A Visit from the Good Squad may seem a hopelessly old-fashioned relic. Such is the power of time.

James Franco also opens his story collection Palo Alto with a selection from In Search of Lost Time, but the effect is severely diminished in his case. First of all, the quoted passage reads:

There is hardly a single action that we perform in that phase which we would not give anything, in later life, to be able to annul. Whereas what we ought to regret is that we no longer possess the spontaneity which made us perform them. In later life we look at things in a more practical way, in full conformity with the rest of society, but adolescence is the only period in which we learn anything.

Though a fitting passage for a work that focuses on young, troubled California teenagers, there is nothing other than the expressed idea that justifies Franco's specific use of Proust as opposed to anyone else. And Franco attributes the quotation to Within a Budding Grove, which is the second book in, as Franco has it here, Remembrance of Things Past. Those two translations of the titles are, by now, somewhat obsolete, the titles of older translations. Within a Budding Grove is now usually referred to as In the Shadows of Young Girls in Flower. There is something a tad disingenuous about Franco's usage here, a more transparently self-conscious attempt to legitimize his stories, something he didn't need to do. His stories, despite some backlash he's received, are pretty good.

Some writers are just masters of the epigraph. Thomas Pynchon always knows an evocative way to open his books. His Against the Day is a vast, panoramic novel that features dozens of characters in as many settings. The story begins at the World's Fair in Chicago in 1893 and goes until the 1920s, a period of remarkable technological change the world over. Electricity had been commercialized and was becoming commonplace. Tesla was conducting all his experiments. Pynchon reduces all of these pursuits to a wonderfully succinct quote:

It's always night, or we wouldn't need light.

–– Thelonious Monk

First of all, have you ever even thought about the universe in this way? That darkness is its default setting? Secondly, have you ever heard a more beautiful and concise explanation for one of the great plights of humanity? We're afraid of the dark, and the desire for light (both literal and metaphorical) consumes us. Referencing Monk does the opposite of referencing Proust. Pynchon's working with high theme here, but he's coming at it with the spirit of a brilliant and erratic jazz artist.

His so-called "beach read," Inherent Vice takes place at the end of the 1960s, an era that clearly means a lot to Pynchon. Earlier, in Vineland, radicals from the 60s have become either irrelevant eccentrics or have joined the establishment. It's a strange, mournful meditation on the failures of free love. Inherent Vice takes a similar approach. Doc Sportello is a disinterested P.I. for whom the promise of that optimistic decade offers very little. That optimism is where we begin the novel:

Under the paving-stones, the beach!

–– Graffito, Paris, May 1968

A very pointed reference. Paris in May of 1968, of course, was a hotbed of protest and civic unrest, a time of strikes and occupations, and, for hippies and radicals, a harbinger of the changes to come. Well, Inherent Vice takes place on a beach. No paving-stones need be removed for the beach to appear. Yet the promise of the graffito –– i.e., that beauty and natural life exist under the surface of the establishment –– seems, to Doc Sportello (and us, as readers, in retrospect) a temporary hope that, like fog, will eventually lift and disappear forever. In the end, as Doc literally drives through a deep fog settling in over Los Angeles, he wonders "how many people he knew had been caught out" in the fog or "were indoors fogbound in front of the tube or in bed just falling asleep." He continues:

Someday...there'd be phones as standard equipment in every car, maybe even dashboard computers. People could exchange names and addresses and life stories and form alumni associations to gather once a year at some bar off a different freeway exit each time, to remember the night they set up a temporary commune to help each other home through the fog.

The fog will lift, and the dream of the 60s will become a memory, murky but present. For Doc, and for us, all he can do is wait "for the fog to burn away, and for something else this time, somehow, to be there instead."

For many, Inherent Vice was a light novel, a nice little diversion, and it mostly is, but for me it has more straightforward (and dare I say, sentimental?) emotional resonance than many of Pynchon's earlier novels. And this epigraph is part of its poignancy. Doc's complicated personal life becomes a panegyric for an entire generation, all in the form of a "beach read."

Sometimes, though, epigraphs offer a different kind of poignancy Christopher Hitchens’s last collection of essays, Arguably, opens with this:

Live all you can: It's a mistake not to.

–– Lambert Strether, in The Ambassadors

Hitchens, by the time Arguably was published, had already been diagnosed with esophageal cancer. He knew he was dying. This epigraph stands as Hitchens's final assertion of his unwavering worldview. Even more retrospectively moving are the epigraphs of Hitch-22, a memoir he wrote before the doctors told him the news. One of these passages is the wonderful, remarkable opening of Hitchens's friend Richard Dawkins's book Unweaving the Rainbow:

We are going to die, and that makes us the lucky ones. Most people are never going to die because they are never going to be born. The potential people who could have been here in my place but who will in fact never see the light of day outnumber the sand grains of the Sahara. Certainly those unborn ghosts include greater poets than Keats, scientists greater than Newton. We know this because the set of possible people allowed by our DNA so massively outnumbers the set of actual people. In the teeth of these stupefying odds it is you and I, in our ordinariness, who are here.

Though I'm not sure how "ordinary" Hitchens viewed himself (he seems to have thought a great deal of himself), this still seems an uncannily prescient sentiment to be quoted so soon before his diagnosis.

But maybe my all-time favorite epigraph comes from Michael Chabon's recent Telegraph Avenue:

Call me Ishmael.

––Ishmael Reed, probably

This is one of the cleverest, funniest, and most arrogant epigraphs I've come across in recent years. "Call me Ishmael" is, as we all know, the opening sentence of Moby Dick. Ishmael Reed was a black experimental novelist, author of the classic Mumbo Jumbo, a writer steeped in African American culture not depicted in mainstream art. Chabon's novel takes place in Oakland and focuses, in part, on race. It is Chabon's most direct attempt to write a Great American Novel (it even suggests as much on the inside flap of the hardcover), with its grand themes and storied setting, its 12-page-long sentence, its general literariness. By framing his book with an irreverent reference to one of America's definitive Great American Novels, placed in the mouth of a black writer, Chabon both announces his intention to write a Great book and denounces the entire notion that there can be Great books. How does the supposed greatness of Moby Dick speak to the black experience? What does its language offer them? So here, the most revered sentence in American literature becomes, for a man named Ishmael, a quotidian utterance, a common request. Call me Ishmael. Just another day for Ishmael Reed. And Telegraph Avenue works like that, too. It's just another day for Archy and Nat, the book's main characters. Is Telegraph Avenue Chabon's Moby Dick? His Ulysses? Perhaps. But it's certainly in conversation with those books; the epigraph makes that much clear.

Epigraphs are, ultimately, like many components of art, in that they can pretty much accomplish anything the writer wants them to. They can support a theme or contradict it. They can prepare readers or mislead them. They can situate a book into its intended company or they can renounce any relationship with the past. And when used effectively, they can be just as vital to a novel's meaning as the title, the themes, the prose. An epigraph may not make or break a book, but it can certainly enhance its richness.

And, more, they can enhance the richness of the epigraph itself. Because of Michael Chabon, I can never look at Moby Dick's famous opening the same way again. When I read Cummings's poem "i sing of Olaf glad and big," I have a new appreciation for its political implications. Literature is wonderful that way. It isn't merely the creation of new work; it's the extension of the art itself. Each new novel, each new story, not only adds to the great well of work, it actually reaches back into the past and changes the static text. It alters how we see the past. The giant conversation of literature knows no restrictions to time or geography, and epigraphs are a big part of it. Writers continuously resurrect the dead, salute the present and, like epigraphs, hint at what's to come in the future.

3.

Now that I think about it, I realize that all those quotes I'd been saving up over the years finally have a purpose. Since I've become a literary critic, I've mined my ever-growing document numerous times, not for an epigraph, but as assistance to my analysis of a literary work. I've used them to characterize a writer's style, their recurring motifs or as examples of their insight. These quotations have become extremely useful, invaluable even. In fact, I see my collection as a kind of epigraph to my own career. At first, I didn't understand their import, but as I lived on (and, appropriately, as I read on), those borrowed words slowly started to announce their purpose, and when I revisit them (like flipping back to the front page of a novel after finishing it), I find they have new meaning to me now. They are the same, but they are different. Like Pynchon writes in Inherent Vice: "What goes around may come around, but it never ends up exactly the same place, you ever notice? Like a record on a turntable, all it takes is one groove’s difference and the universe can be on into a whole ‘nother song.”

Most Anticipated: The Great Second-Half 2013 Book Preview

The first half of 2013 delighted us with new books by the likes of George Saunders, Karen Russell, and Colum McCann, among many others. And if the last six months had many delights on offer for book lovers, the second half of the year can only be described as an invitation to gluttony. In the next six months, you'll see new books by Jhumpa Lahiri, Margaret Atwood, Donna Tartt, Marisha Pessl, Norman Rush, Jonathan Lethem, and none other than Thomas Pynchon. And beyond those headliners there are many other tantalizing titles in the wings, including some from overseas and others from intriguing newcomers.

The list that follows isn’t exhaustive – no book preview could be – but, at 9,000 words strong and encompassing 86 titles, this is the only second-half 2013 book preview you will ever need. Scroll down and get started.

July:

Visitation Street by Ivy Pochoda: Crime writer Dennis Lehane chose Pochoda’s lyrical and atmospheric second novel for his eponymous imprint at Ecco/Harper, calling it “gritty and magical.” Pitched as a literary thriller about the diverse inhabitants of Red Hook, Brooklyn, Visitation Street has already received starred reviews from Publisher’s Weekly, Kirkus Reviews, and Library Journal. Lionel Shriver says, “I loved it,” and Deborah Harkness calls it “marvelous.” (Edan)

Love, Dishonor, Marry, Die, Cherish, Perish by David Rakoff: Rakoff was the author of three books of essays, the winner of the Thurber Prize for American Humor, and a beloved regular on This American Life who died last year shortly after finishing this book. A novel written entirely in verse (a form in which he was masterful, as evidenced here), its characters range across the 20th century, each connected to the next by an act of generosity or cruelty. (Janet)

The Love Affairs of Nathaniel P. by Adelle Waldman: Waldman recently weighed in for us on the centuries-old Richardson vs. Fielding debate. Now, in her first novel, she expertly plays the former's psychological penetration off the latter's civic vision. The titular Nathaniel, one of Brooklyn's sad young literary men, seeks to navigate between his public ambitions and his private compulsions in a series of romantic encounters. Those without 718 area codes shouldn't let the milieu scare them off; questions of whether Nate can heed the difficult imperatives of the conscience—and of how Waldman will pull off a whole book from the man's point of view—keep the pages turning, while generating volumes of quotable insight, in the manner of The Marriage Plot. (Garth)

Fin & Lady by Cathleen Schine: A country mouse moves to the city in Cathleen Schine’s ninth novel. The mouse is Fin, an orphaned eleven-year old boy, and the city is Greenwich Village in the 1960s. Under the guardianship of his glamorous half-sister, Lady, Fin gets to know both the city and his wild sister, and encounters situations that are a far cry from his Connecticut dairy farm upbringing. As with many of Schine’s previous novels, Fin & Lady explores changing definitions of family. (Hannah)

My Education by Susan Choi: Reflect upon your sordid graduate school days with a novel of the perverse master-student relationship and adulterous sex triangle. Professor Brodeur is evidently the kind of man whose name is scrawled on restroom walls by vengeful English majors—rather than end up in the sack with him, Choi’s protagonist Regina instead starts up an affair with his wife. Later in the novel and in time, Regina reflects on this period in her life and the changes wrought by the intervening 15 years. Choi was a Pulitzer Prize finalist for her second novel, American Woman. (Lydia)

Five Star Billionaire by Tash Aw: The third novel from the winner of the 2005 Whitbread First Novel Award follows the lives and business ventures of five characters in Shanghai, each representing various—and at times dichotomous—social strata. There’s Phoebe, the poor and unsophisticated migrant worker from Malaysia; and there’s Yinghui, the rich and ambitious businesswoman. There’s Gary, the waylaid pop star; and there’s Justin, the scion of a wealthy real estate family. Lastly there’s Walter, the eponymous billionaire, who meddles behind the scenes with the lives of almost everybody. Altogether, their multi-layered, intersecting lives contribute to make “Shanghai itself [into] the book’s real main character,” writes Jill Baker in the Asian Review of Books. It’s a city “luring in people hoping for a second chance or … any chance at all.” (Nick)

Lotería by Mario Alberto Zambrano: It’s a rare first novel that can appeal to partisans of both S.E. Hinton and Julio Cortázar, but Lotería does just that. The story 11-year-old Luz Maria Castillo begins telling us from her room in a state institution is deceptively plainspoken: Here’s how I got here. But as the story proceeds in fragments, keyed not to chronology but to a deck of cards from Lotería (a kind of Mexican bingo), things get shiftier. Color reproductions of the cards introduce each chapter, making the book, if not exactly Kindle-proof, then at least uncommonly handsome. (Garth)

The Unknowns by Gabriel Roth: Gabriel Roth’s debut novel follows Eric Muller from his lonely high school days as a computer geek to his millionaire success in Silicon Valley as a computer geek. Slightly disoriented by his newfound abilities to make money and bed women, Muller wryly observes his life as if he is that same awkward teenager trapped in a dream life. When he falls in love with Maya, a beautiful woman with a mysterious past, he must choose between the desire to emotionally (and literally) hack into it, or to trust his good fortune. (Janet)

The Hare by César Aira: A recent bit of contrarianism in The New Republic blamed the exhaustive posthumous marketing of Roberto Bolaño for crowding other Latin American writers out of the U.S. marketplace. If anything, it seems to me, it’s the opposite: the success of The Savage Detectives helped publishers realize there was a market for Daniel Sada, Horacio Castellanos Moya, and the fascinating Argentine César Aira. The past few years have seen seven of Aira’s many novels translated into English. Some of them, like Ghosts, are transcendently good, but none has been a breakout hit. Maybe the reissue of The Hare, which appeared in the U.K. in 1998, will be it. At the very least, it’s the longest Aira to appear in English: a picaresque about a naturalist’s voyage into the Argentinean pampas. (Garth)

August:

Night Film by Marisha Pessl: Pessl’s first novel since Special Topics in Calamity Physics, her celebrated 2006 debut, concerns a David Lynchish filmmaker whose daughter has died in Lower Manhattan under suspicious circumstances. Soon, reporter Scott McGrath has launched an investigation that will take him to the heart of the auteur’s secretive empire: his cult following, his whacked-out body of work, and his near impenetrable upstate compound. With interpolated web pages and documents and Vanity Fair articles, the novel’s a hot pop mess, but in the special way of a latter-day Kanye West album or a movie co-directed by Charlie Kaufman and Michael Bay, and the climax alone—a 65-page haunted-house tour-de-force—is worth the price of admission. (Garth)