Mentioned in:

A Year in Reading: 2024

Welcome to the 20th (!) installment of The Millions' annual Year in Reading series, which gathers together some of today's most exciting writers and thinkers to share the books that shaped their year. YIR is not a collection of yearend best-of lists; think of it, perhaps, as an assemblage of annotated bibliographies. We've invited contributors to reflect on the books they read this year—an intentionally vague prompt—and encouraged them to approach the assignment however they choose.

In writing about our reading lives, as YIR contributors are asked to do, we inevitably write about our personal lives, our inner lives. This year, a number of contributors read their way through profound grief and serious illness, through new parenthood and cross-country moves. Some found escape in frothy romances, mooring in works of theology, comfort in ancient epic poetry. More than one turned to the wisdom of Ursula K. Le Guin. Many describe a book finding them just when they needed it.

Interpretations of the assignment were wonderfully varied. One contributor, a music critic, considered the musical analogs to the books she read, while another mapped her reads from this year onto constellations. Most people's reading was guided purely by pleasure, or else a desire to better understand events unfolding in their lives or larger the world. Yet others centered their reading around a certain sense of duty: this year one contributor committed to finishing the six Philip Roth novels he had yet to read, an undertaking that he likens to “eating a six-pack of paper towels.” (Lucky for us, he included in his essay his final ranking of Roth's oeuvre.)

The books that populate these essays range widely, though the most commonly noted title this year was Tony Tulathimutte’s story collection Rejection. The work of newly minted National Book Award winner Percival Everett, particularly his acclaimed novel James, was also widely read and written about. And as the genocide of Palestinians in Gaza enters its second year, many contributors sought out Isabella Hammad’s searing, clear-eyed essay Recognizing the Stranger.

Like so many endeavors in our chronically under-resourced literary community, Year in Reading is a labor of love. The Millions is a one-person editorial operation (with an invaluable assist from SEO maven Dani Fishman), and producing YIR—and witnessing the joy it brings contributors and readers alike—has been the highlight of my tenure as editor. I’m profoundly grateful for the generosity of this year’s contributors, whose names and entries will be revealed below over the next three weeks, concluding on Wednesday, December 18. Be sure to subscribe to The Millions’ free newsletter to get the week’s entries sent straight to your inbox each Friday.

—Sophia Stewart, editor

Becca Rothfeld, author of All Things Are Too Small

Carvell Wallace, author of Another Word for Love

Charlotte Shane, author of An Honest Woman

Brianna Di Monda, writer and editor

Nell Irvin Painter, author of I Just Keep Talking

Carrie Courogen, author of Miss May Does Not Exist

Ayşegül Savaş, author of The Anthropologists

Zachary Issenberg, writer

Tony Tulathimutte, author of Rejection

Ann Powers, author of Traveling: On the Path of Joni Mitchell

Lidia Yuknavitch, author of Reading the Waves

Nicholas Russell, writer and critic

Daniel Saldaña París, author of Planes Flying Over a Monster

Lili Anolik, author of Didion and Babitz

Deborah Ghim, editor

Emily Witt, author of Health and Safety

Nathan Thrall, author of A Day in the Life of Abed Salama

Lena Moses-Schmitt, author of True Mistakes

Jeremy Gordon, author of See Friendship

John Lee Clark, author of Touch the Future

Ellen Wayland-Smith, author of The Science of Last Things

Edwin Frank, publisher and author of Stranger Than Fiction

Sophia Stewart, editor of The Millions

A Year in Reading Archives: 2023, 2022, 2021, 2020, 2019, 2018, 2017, 2016, 2015, 2014, 2013, 2011, 2010, 2009, 2008, 2007, 2006, 2005

The Great Fall 2024 Book Preview

With the arrival of autumn comes a deluge of great books. Here you'll find a sampling of new and forthcoming titles that caught our eye here at The Millions, and that we think might catch yours, too. Some we’ve already perused in galley form; others we’re eager to devour based on their authors, plots, or subject matters. We hope your next fall read is among them.

—Sophia Stewart, editor

October

Season of the Swamp by Yuri Herrera, tr. Lisa Dillman [F]

What it is: An epic, speculative account of the 18 months that Benito Juárez spent in New Orleans in 1853-54, years before he became the first and only Indigenous president of Mexico.

Who it's for: Fans of speculative history; readers who appreciate the magic that swirls around any novel set in New Orleans. —Claire Kirch

The Black Utopians by Aaron Robertson [NF]

What it is: An exploration of Black Americans' pursuit and visions of utopia—both ideological and physical—that spans the Reconstruction era to the present day and combines history, memoir, and reportage.

Who it's for: Fans of Saidiya Hartman's Wayward Lives, Beautiful Experiments and Kristen R. Ghodsee's Everyday Utopia. —Sophia M. Stewart

The Third Realm by Karl Ove Knausgaard, tr. Martin Aitken [F]

What it is: The third installment in Knausgaard's Morning Star series, centered on the appearance of a mysterious new star in the skies above Norway.

Who it's for: Real Knausgaard heads only—The Wolves of Eternity and Morning Star are required reading for this one. —SMS

Brown Women Have Everything by Sayantani Dasgupta [NF]

What it is: Essays on the contradictions and complexities of life as an Indian woman in America, probing everything from hair to family to the joys of travel.

Who it's for: Readers of Durga Chew-Bose, Erika L. Sánchez, and Tajja Isen. —SMS

The Plot Against Native America by Bill Vaughn [F]

What it is: The first narrative history of Native American boarding schools— which aimed "civilize" Indigenous children by violently severing them from their culture— and their enduring, horrifying legacy.

Who it's for: Readers of Ned Blackhawk and Kathleen DuVal. —SMS

The Mighty Red by Louise Erdrich [F]

What it is: Erdrich's latest novel set in North Dakota's Red River Valley is a tale of the intertwined lives of ordinary people striving to survive and even thrive in their rural community, despite environmental upheavals, the 2008 financial crisis, and other obstacles.

Who it's for: Readers of cli-fi; fans of Linda LeGarde Grover and William Faulkner. —CK

The Position of Spoons by Deborah Levy [NF]

What it is: The second book from Levy in as many years, diverging from a recent streak of surrealist fiction with a collection of essays marked by exceptional observance and style.

Who it's for: Close lookers and the perennially curious. —John H. Maher

The Bog Wife by Kay Chronister [F]

What it's about: The Haddesley family has lived on the same West Virginia bog for centuries, making a supernatural bargain with the land—a generational blood sacrifice—in order to do so—until an uncovered secret changes everything.

Who it's for: Readers of Karen Russell and Jeff VanderMeer; anyone who has ever used the phrase "girl moss." —SMS

The Great When by Alan Moore [F]

What it's about: When an 18-year old book reseller comes across a copy of a book that shouldn’t exist, it threatens to upend not just an already post-war-torn London, but reality as we know it.

Who it's for: Anyone looking for a Sherlock Holmes-style mystery dipped in thaumaturgical psychedelia. —Daniella Fishman

The Message by Ta-Nehisi Coates [NF]

What it's about: One of our sharpest critical thinkers on social justice returns to nonfiction, nearly a decade after Between the World and Me, visiting Dakar, to contemplate enslavement and the Middle Passage; Columbia, S.C., as a backdrop for his thoughts on Jim Crow and book bans; and the Israeli-occupied West Bank, where he sees contemporary segregation in the treatment of Palestinians.

Who it’s for: Fans of James Baldwin, George Orwell, and Angela Y. Davis; readers of Nikole Hannah-Jones’s The 1619 Project and Isabel Wilkerson’s Caste, to name just a few engagements with national and racial identity. —Nathalie op de Beeck

Abortion by Jessica Valenti [NF]

What it is: Columnist and memoirist Valenti, who tracks pro-choice advocacy and attacks on the right to choose in her Substack, channels feminist rage into a guide for freedom of choice advocacy.

Who it’s for: Readers of Robin Marty’s The New Handbook for a Post-Roe America, #ShoutYourAbortion proponents, and followers of Jennifer Baumgartner’s [I Had an Abortion] project. —NodB

Gifted by Suzuki Suzumi, tr. Allison Markin Powell [F]

What it's about: A young sex worker in Tokyo's red-light district muses on her life and recounts her abusive mother's final days, in what is Suzuki's first novel to be translated into English.

Who it's for: Readers of Susan Boyt and Mieko Kanai; fans of moody, introspective fiction; anyone with a fraught relationship to their mother. —SMS

Childish Literature by Alejandro Zambra, tr. Megan McDowell [F]

What it is: A wide-ranging collection of stories, essays, and poems that explore childhood, fatherhood, and family.

Who it's for: Fans of dad lit (see: Lucas Mann's Attachments, Keith Gessen's Raising Raffi, Karl Ove Knausgaard's seasons quartet, et al). —SMS

Books Are Made Out of Books ed. Michael Lynn Crews [NF]

What it is: A mining of the archives of the late Cormac McCarthy with a focus on the famously tight-lipped author's literary influences.

Who it's for: Anyone whose commonplace book contains the words "arquebus," "cordillera," or "vinegaroon." —JHM

Slaveroad by John Edgar Wideman [F]

What it is: A blend of memoir, fiction, and history that charts the "slaveroad" that runs through American history, spanning the Atlantic slave trade to the criminal justice system, from the celebrated author of Brothers and Keepers.

Who it's for: Fans of Clint Smith and Ta-Nehisi Coates. —SMS

Linguaphile by Julie Sedivy [NF]

What it's about: Linguist Sedivy reflects on a life spent loving language—its beauty, its mystery, and the essential role it plays in human existence.

Who it's for: Amateur (or professional) linguists; fans of the podcast A Way with Words (me). —SMS

An Image of My Name Enters America by Lucy Ives [NF]

What it is: A collection of interrelated essays that connect moments from Ives's life to larger questions of history, identity, and national fantasy,

Who it's for: Fans of Ives, one of our weirdest and most wondrous living writers—duh; anyone with a passing interest in My Little Pony, Cold War–era musicals, or The Three Body Problem, all of which are mined here for great effect. —SMS

Women's Hotel by Daniel Lavery [F]

What it is: A novel set in 1960s New York City, about the adventures of the residents of a hotel providing housing for young women that is very much evocative of the real-life legendary Barbizon Hotel.

Who it's for: Readers of Mary McCarthy's The Group and Rona Jaffe's The Best of Everything. —CK

The World in Books by Kenneth C. Davis [NF]

What it is: A guide to 52 of the most influential works of nonfiction ever published, spanning works from Plato to Ida B. Wells, bell hooks to Barbara Ehrenreich, and Sun Tzu to Joan Didion.

Who it's for: Lovers of nonfiction looking to cover their canonical bases. —SMS

Blue Light Hours by Bruna Dantas Lobato [F]

What it's about: Through the emanating blue-glow of their computer screens, a mother and daughter, four-thousand miles apart, find solace and loneliness in their nightly Skype chats in this heartstring-pulling debut.

Who it's for: Someone who needs to be reminded to CALL YOUR MOTHER! —DF

Riding Like the Wind by Iris Jamahl Dunkle [NF]

What it is: The biography of Sanora Babb, a contemporary of John Steinbeck's whose field notes and interviews with Dust Bowl migrants Steinbeck relied upon to write The Grapes of Wrath.

Who it's for: Steinbeck fans and haters alike; readers of Kristin Hannah's The Four Winds and the New York Times Overlooked column; anyone interested in learning more about the Dust Bowl migrants who fled to California hoping for a better life. —CK

Innie Shadows by Olivia M. Coetzee [F]

What it is: a work of crime fiction set on the outskirts of Cape Town, where a community marred by violence seeks justice and connection; also the first novel to be translated from Kaaps, a dialect of Afrikaans that was until recently only a spoken language.

Who it's for: fans of sprawling, socioeconomically-attuned crime dramas a la The Wire. —SMS

Dorothy Parker in Hollywood by Gail Crowther [NF]

What it is: A history of the famous wit—and famous New Yorker—in her L.A. era, post–Algonquin Round Table and mid–Red Scare.

Who it's for: Owners of a stack of hopelessly dog-eared Joan Didion paperbacks. —JHM

The Myth of American Idealism by Noam Chomsky and Nathan J. Robinson [NF]

What it is: A potent critique of the ideology behind America's foreign interventions and its status as a global power, and an treatise on how the nation's hubristic pursuit of "spreading democracy" threatens not only the delicate balance of global peace, but the already-declining health of our planet.

Who it's for: Chomskyites; policy wonks and casual critics of American recklessness alike. —DF

Mysticism by Simon Critchley [NF]

What it is: A study of mysticism—defined as an experience, rather than religious practice—by the great British philosopher Critchley, who mines music, poetry, and literature along the way.

Who it's for: Readers of John Gray, Jorge Luis Borges, and Simone Weil. —SMS

Q&A by Adrian Tomine [NF]

What it is: The Japanese American creator of the Optic Nerve comic book series for D&Q, and of many a New Yorker cover, shares his personal history and his creative process in this illustrated unburdening.

Who it’s for: Readers of Tomine’s melancholic, sometimes cringey, and occasionally brutal collections of comics short stories including Summer Blonde, Shortcomings, and Killing and Dying. —NodB

Sonny Boy by Al Pacino [NF]

What it is: Al Pacino's memoir—end of description.

Who it's for: Cinephiles; anyone curious how he's gonna spin fumbling Diane Keaton. —SMS

Seeing Baya by Alice Kaplan [NF]

What it is: The first biography of the enigmatic and largely-forgotten Algerian artist Baya Mahieddine, who first enchanted midcentury Paris as a teenager.

Who it's for: Admirers of Leonora Carrington, Hilma af Klint, Frida Kahlo, and other belatedly-celebrated women painters. —SMS

Absolution by Jeff VanderMeer [F]

What it is: A surprise return to the Area X, the stretch of unforbidding and uncanny coastline in the hit Southern Reach trilogy.

Who it's for: Anyone who's heard this song and got the reference without Googling it. —JHM

The Four Horsemen by Nick Curtola [NF]

What it is: The much-anticipated cookbook from the team behind Brooklyn's hottest restaurant (which also happens to be co-owned by James Murphy of LCD Soundsystem).

Who it's for: Oenophiles; thirty-somethings who live in north Williamsburg (derogatory). —SMS

Seeing Further by Esther Kinsky, tr. Caroline Schmidt [F]

What it's about: An unnamed German woman embarks on the colossal task of reviving a cinema in a small Hungarian village.

Who it's for: Fans of Jenny Erpenbeck; anyone charmed by Cinema Paradiso (not derogatory!). —SMS

Ripcord by Nate Lippens [NF]

What it's about: A novel of class, sex, friendship, and queer intimacy, written in delicious prose and narrated by a gay man adrift in Milwaukee.

Who it's for: Fans of Brontez Purnell, Garth Greenwell, Alexander Chee, and Wayne Koestenbaum. —SMS

The Use of Photography by Annie Ernaux and Marc Marie, tr. Alison L. Strayer [NF]

What it's about: Ernaux's love affair with Marie, a journalist, while she was undergoing treatment for cancer, and their joint project to document their romance.

Who it's for: The Ernaux hive, obviously; readers of Sontag's On Photography and Janet Malcolm's Still Pictures. —SMS

Nora Ephron at the Movies by Ilana Kaplan [NF]

What it is: Kaplan revisits Nora Ephron's cinematic watersheds—Silkwood, Heartburn, When Harry Met Sally, You've Got Mail, and Sleepless in Seattle—in this illustrated book. Have these iconic stories, and Ephron’s humor, weathered more than 40 years?

Who it’s for: Film history buffs who don’t mind a heteronormative HEA; listeners of the Hot and Bothered podcast; your coastal grandma. —NodB

[millions_email]

The Philosophy of Translation by Damion Searls [NF]

What it is: A meditation on the act and art of translation by one of today's most acclaimed practitioners, best known for his translations of Fosse, Proust, et al.

Who it's for: Regular readers of Words Without Borders and Asymptote; professional and amateur literary translators alike. —SMS

Salvage by Dionne Brand

What it is: A penetrating reevaluation of the British literary canon and the tropes once shaped Brand's reading life and sense of self—and Brand’s first major work of nonfiction since her landmark A Map to the Door of No Return.

Who it's for: Readers of Christina Sharpe's Ordinary Notes and Elizabeth Hardwick's Seduction and Betrayal. —SMS

Masquerade by Mike Fu [F]

What it's about: Housesitting for an artist friend in present-day New York, Meadow Liu stumbles on a novel whose author shares his name—the first of many strange, haunting happenings that lead up to the mysterious disappearance of Meadow's friend.

Who it's for: fans of Ed Park and Alexander Chee. —SMS

November

The Beggar Student by Osamu Dazai, tr. Sam Bett [F]

What it is: A novella in the moody vein of Dazai’s acclaimed No Longer Human, following the 30-something “fictional” Dazai into another misadventure spawned from a hubristic spat with a high schooler.

Who it's for: Longtime readers of Dazai, or new fans who discovered the midcentury Japanese novelist via TikTok and the Bungo Stray Dogs anime. —DF

In Thrall by Jane DeLynn [F]

What it is: A landmark lesbian bildungsroman about 16-year-old Lynn's love affair with her English teacher, originally published in 1982.

Who it's for: Fans of Joanna Russ's On Strike Against God and Edmund White's A Boy's Own Story —SMS

Washita Love Child by Douglas Kent Miller [NF]

What it is: The story of Jesse Ed Davis, the Indigenous musician who became on of the most sought after guitarists of the late '60s and '70s, playing alongside B.B. King, Bob Dylan, John Lennon, and more.

Who it's for: readers of music history and/or Indigenous history; fans of Joy Harjo, who wrote the foreword. —SMS

Set My Heart on Fire by Izumi Suzuki, tr. Helen O'Horan [F]

What it is: Gritty, sexy, and wholly rock ’n’ roll, Suzuki’s first novel translated into English (following her story collection, Hit Parade of Tears) follows 20-year-old Izumi navigating life, love, and music in the underground scene in '70s Japan.

Who it's for: Fans of Meiko Kawakami, Ursula K. Le Guin, and Marlowe Granados's Happy Hour. —DF

Didion & Babitz by Lili Anolik [NF]

What it is: A dual portrait of Joan Didion and Eve Babitz, who are so often compared to—and pitted against—each other on the basis of their mutual Los Angeles milieu.

Who it's for: Fans or haters of either writer (the book is fairly pro-Babitz, often at Didion's expense); anyone who has the Lit Hub Didion tote bag. —SMS

The Endless Refrain by David Rowell [NF]

What it's about: How the rise of music streaming, demonitizing of artist revenue, and industry tendency toward nostalgia have laid waste to the musical landscape, and the future of music culture.

Who it's for: Fans of Kyle Chayka, Spence Kornhaber, and Lindsay Zoladz. —SMS

Every Arc Bends Its Radian by Sergio De La Pava [F]

What it is: A mind- and genre-bending detective story set in Cali, Colombia, that blends high-stakes suspense with rigorous philosophy.

Who it's for: Readers of Raymond Chandler, Thomas Pynchon, and Jules Verne. —SMS

Something Close to Nothing by Tom Pyun [F]

What it’s about: At the airport with his white husband Jared, awaiting a flight to Cambodia to meet the surrogate mother carrying their adoptive child-to-be, Korean American Wynn decides parenthood isn't for him, and bad behavior ensues.

Who it’s for: Pyun’s debut is calculated to cut through saccharine depictions of queer parenthood—could pair well with Torrey Peters’s Detransition, Baby. —NodB

Rosenfeld by Maya Kessler [F]

What it is: Kessler's debut—rated R for Rosenfeld—follows one Noa Simmons through the tumultuous and ultimately profound power play that is courting (and having a lot of sex with) the titular older man who soon becomes her boss.

Who it's for: Fans of Sex and the City, Raven Leilani’s Luster, and Coco Mellor’s Cleopatra and Frankenstein. —DF

Lazarus Man by Richard Price [F]

What it is: The former The Wire writer offers yet another astute chronicle of urban life, this time of an ever-changing Harlem.

Who it's for: Fans of Colson Whitehead's Crook Manifesto and Paul Murray's The Bee Sting—and, of course, The Wire. —SMS

Stranger Than Fiction by Edwin Frank [NF]

What it is: An astute curveball of a read on the development and many manifestations of the novel throughout the tumultuous 20th century.

Who it's for: Readers who look at a book's colophon before its title. —JHM

Letters to His Neighbor by Marcel Proust, tr. Lydia Davis

What it is: A collection of Proust’s tormented—and frequently hilarious—letters to his noisy neighbor which, in a diligent translation from Davis, stand the test of time.

Who it's for: Proust lovers; people who live below heavy-steppers. —DF

Context Collapse by Ryan Ruby [NF]

What it is: A self-proclaimed "poem containing a history of poetry," from ancient Greece to the Iowa Workshop, from your favorite literary critic's favorite literary critic.

Who it's for: Anyone who read and admired Ruby's titanic 2022 essay on The Waste Land; lovers of poetry looking for a challenge. —SMS

How Sondheim Can Change Your Life by Richard Schoch [NF]

What it's about: Drama professor Schoch's tribute to Stephen Sondheim and the life lessons to be gleaned from his music.

Who it's for: Sondheim heads, former theater kids, end of list. —SMS

The Serviceberry by Robin Wall Kimmerer [NF]

What it is: 2022 MacArthur fellow and botanist Kimmerer, an enrolled member of the Citizen Potawatomi Nation, (re)introduces audiences to a flowering, fruiting native plant beloved of foragers and gardeners.

Who it’s for: The restoration ecologist in your life, along with anyone who loved Braiding Sweetgrass and needs a nature-themed holiday gift. —NodB

My Heart Belongs in an Empty Big Mac Container Buried Beneath the Ocean Floor by Homeless [F]

What it is: A pseudonymous, tenderly comic novel of blue whales and Golden Arches, mental illness and recovery.

Who it's for: Anyone who finds Thomas Pynchon a bit too staid. —JHM

Yoke and Feather by Jessie van Eerden [NF]

What it's about: Van Eerden's braided essays explore the "everyday sacred" to tease out connections between ancient myth and contemporary life.

Who it's for: Readers of Courtney Zoffness's Spilt Milk and Jeanna Kadlec's Heretic. —SMS

Camp Jeff by Tova Reich [F]

What it's about: A "reeducation" center for sex pests in the Catskills, founded by one Jeffery Epstein (no, not that one), where the dual phenomena of #MeToo and therapyspeak collide.

Who it's for: Fans of Philip Roth and Nathan Englander; cancel culture skeptics. —SMS

Selected Amazon Reviews by Kevin Killian [NF]

What it is: A collection of 16 years of Killian’s funniest, wittiest, and most poetic Amazon reviews, the sheer number of which helped him earn the rarefied “Top 100” and “Hall of Fame” status on the site.

Who it's for: Fans of Wayne Koestenbaum and Dodie Bellamy, who wrote introduction and afterword, respectively; people who actually leave Amazon reviews. —DF

Cher by Cher [NF]

What it is: The first in a two-volume memoir, telling the story of Cher's early life and ascendent career as only she can tell it.

Who it's for: Anyone looking to fill the My Name Is Barbra–sized hole in their heart, or looking for something to tide them over until the Liza memoir drops. —SMS

The City and Its Uncertain Walls by Haruki Murakami, tr. Philip Gabriel [F]

What it is: Murakami’s first novel in over six years returns to the high-walled city from his 1985 story "Hard-Boiled Wonderland and the End of the World" with one man's search for his lost love—and, simultaneously, an ode to libraries and literature itself.

Who it's for: Murakami fans who have long awaited his return to fiction. —DF

American Bulk by Emily Mester [NF]

What it's about: Reflecting on what it means to "live life to the fullest," Mester explores the cultural and personal impacts of America’s culture of overconsumption, from Costco hauls to hoarding to diet culture—oh my!

Who it's for: Lovers of sustainability; haters of excess; skeptics of the title essay of Becca Rothfeld's All Things Are Too Small. —DF

The Icon and the Idealist by Stephanie Gorton [NF]

What it is: A compelling look at the rivalry between Margaret Sanger, of Planned Parenthood fame, and Mary Ware Dennett, who each held radically different visions for the future of birth control.

Who it's for: Readers of Amy Sohn's The Man Who Hated Women and Katherine Turk's The Women of NOW; anyone interested in the history of reproductive rights. —SMS

December

Rental House by Weike Wang [F]

What it's about: Married college sweethearts invite their drastically different families on a Cape Code vacation, raising questions about marriage, intimacy, and kinship.

Who it's for: Fans of Wang's trademark wit and sly humor (see: Joan Is Okay and Chemistry); anyone with an in-law problem.

Woo Woo by Ella Baxter [F]

What it's about: A neurotic conceptual artist loses her shit in the months leading up to an exhibition that she hopes will be her big breakout, poking fun at the tropes of the "art monster" and the "woman of the verge" in one fell, stylish swoop.

Who it's for: Readers of Sheena Patel's I'm a Fan and Chris Kraus's I Love Dick; any woman who is grateful to but now also sort of begrudges Jenny Offil for introducing "art monster" into the lexicon (me). —SMS

Berlin Atomized by Julia Kornberg, tr. Jack Rockwell and Julia Kornberg [F]

What it's about: Spanning 2001 to 2034, three Jewish and downwardly mobile siblings come of age in various corners of the world against the backdrop of global crisis.

Who it's for: Fans of Catherine Lacey's Biography of X and Joshua Cohen's The Netanyahus. —SMS

Sand-Catcher by Omar Khalifah, tr. Barbara Romaine [F]

What it is: A suspenseful, dark satire of memory and nation, in which four young Palestinian journalists at a Jordanian newspaper are assigned to interview an elderly witness to the Nakba, the violent 1948 expulsion of native Palestinians from Israel—but to their surprise, the survivor doesn’t want to rehash his trauma for the media.

Who it’s for: Anyone looking insight—tinged with grim humor—into the years leading up to the present political crisis in the Middle East and the decades-long goal of Palestinian autonomy. —NodB

The Shutouts by Gabrielle Korn [F]

What it's about: In the dystopian future, mysteriously connected women fight to survive on the margins of society amid worsening climate collapse.

Who it's for: Fans of Korn's Yours for the Taking, which takes place in the same universe; readers of Becky Chambers and queer-inflected sci-fi. —SMS

What in Me Is Dark by Orlando Reade [NF]

What it's about: The enduring, evolving influence of Milton's Paradise Lost on political history—and particularly on the work of 12 revolutionary readers, including Malcom X and Hannah Arendt.

Who it's for: English majors and fans of Ryan Ruby and Sarah Bakewell—but I repeat myself. —SMS

The Afterlife Is Letting Go by Brandon Shimoda [NF]

What it's about: Shimoda researches the mass incarceration of Japanese Americans during WWII, and speaks with descendants of those imprisoned, for this essay collection about the “afterlife” of cruelty and xenophobia in the U.S.

Who it’s for: Anyone to ever visit a monument, museum, or designated site of hallowed ground where traumatic events have taken place. —NodB

No Place to Bury the Dead by Karina Sainz Borgo, tr. Elizabeth Bryer [F]

What it's about: When Angustias Romero loses both her children while fleeing a mysterious disease in her unnamed Latin American country, she finds herself in a surreal, purgatorial borderland where she's soon caught in a power struggle.

Who it's for: Fans of Maríana Enriquez and Mohsin Hamid. —SMS

The Rest Is Silence by Augusto Monterroso, tr. Aaron Kerner [F]

What it is: The author of some of the shortest, and tightest, stories in Latin American literature goes long with a metafictional skewering of literary criticism in his only novel.

Who it's for: Anyone who prefers the term "palm-of-the-hand stories" to "flash fiction." —JHM

Tali Girls by Siamak Herawi, tr. Sara Khalili [F]

What it is: An intimate, harrowing, and vital look at the lives of girls and women in an Afghan mountain village under Taliban rule, based on true stories.

Who it's for: Readers of Nadia Hashimi, Akwaeke Emezi, and Maria Stepanova. —SMS

Sun City by Tove Jansson, tr. Thomas Teal [F]

What it's about: During her travels through the U.S. in the 1970s, Jansson became interested in the retirement home as a peculiarly American institution—here, she imagines the tightly knit community within one of them.

Who it's for: Fans of Jansson's other fiction for adults, much of which explores the lives of elderly folks; anyone who watched that documentary about The Villages in Florida. —SMS

Editor's note: We're always looking to make our seasonal book previews more useful to the readers, writers, and critics they're meant to serve. Got an idea for how we can improve our coverage? Tell me about it at sophia@themillions.com.

[millions_email]

A Year in Reading: Dustin Kurtz

Had a fun year this past year. No real reason for it. Ever have one of those? Just a good time. Each morning waking up, feeling swell. Glad to be awake. Each day not only a joy but memorable, you know? The kind you’re proud to tell your kid about. Days where you hate to shut your eyes, put an end to them. Nights swaddled in a rich thick sleep. Brain full of health and juices, taut, toothsome, like a lychee. Just a good year. How are things, people ask. Great, you say. Things are great.

The thing with having a swell year is that you spend a lot of your time kind of trying to get yourself as close to a state of big blank noise as you can. Like, degrade your waveform down into the background hiss, you know? Get the pitch of the nothing in your head closer to the pitch of the bigger nothing. On account of how good you feel. One way to do that is to stare at your phone, mouth open as if you’re gagging. Maybe make an animal whine. Importantly, reading a book is not a good means to that end. Chalk it up in the How Books Are Bad column, I guess: They shore you up as a reading subject instead of letting you blur out. What a misdeed. Probably we should stop making them. Or, me specifically, I should. Again, due to feeling good.

I read a few books in spite of that. Enjoyed some of those. Cried at most, probably. A real softy. That’s the hell of it, right? To still be there enough that the weather can blow you around a bit. If I’m gonna live with a crow in my mouth let it have the decency to stay there. It’s the coming and going, when you sort of realize how to move your mouth again, wiggle that jaw, close that throat, but you know the damned thing’ll come back to roost, that’s what’ll get you.

One note: I work for Catapult / Counterpoint / Soft Skull. I talk about their books online. Part of that job means being fair in the mention I give to our authors. Because of that, I won’t be mentioning any of our own books here, though they make up the bulk of my reading life. There isn’t space to talk about them all, so I won’t pick and choose.

I read A Maggot by John Fowles. Had this one on my shelf for a while. Only the second of his I’ve read, after that little book about trees and fathers. This one was a real delight, an epistolary murder mystery set in eighteenth century Britain—Exmoor among other places—involving puritans, Stonehenge, sex, satanic panic, jurisprudence and a hard pivot into the fantastic. I love thinking about the mood of this alongside some of the recent work of M. John Harrison.

Reminded me, too, of parts of The Return of the Native, some of which I reread this year, as I’ve done every year lately. When he hides under the turf. The cart tucked away in a firelit cleft. The well. The mummers, outside in the cold waiting to enter. People mention Hardy’s cruelty to his characters but his greater cruelty is in reminding us again and again of the grave we miss but to which we can’t find the way back.

Another book I reread every year is After Ikkyu by Jim Harrison. These are poems, most of them toying with zen practice. They’re extremely Harrison—that is to say, they revel in a kind of needy gruffness, a deflation of romance, gentle horniness, some mourning, some birds and rocks thrown in for the hell of it. His dog sleeps on his zabuton. My admiration for Harrison is my northern Michigan birthright and I don’t expect I’ll shake it any time soon.

I read three chapbooks from speCT! Books in Oakland: Wildfires by my old colleague Will Vincent, Delphiniums by Amanda Nadelberg and selected emails by Jan-Henry Gray and enjoyed them all. The last is, ostensibly, a transcription of email from author to publisher leading up to the creation of itself, the chapbook, as an object. It engages directly with anxieties of creation, of deadlines, and—something poetry sidesteps as a rule—issues of veracity. If you work in publishing it will make you pale with inbox panic.

I read Wayward Heroes by Halldor Laxness, translated by Philip Roughton. Brilliant brilliant book. A novel that situates the heroics that inform the Poetic Edda in a more materialist context. The result is that the heroes look and speak like absolute psychopaths, go around slaughtering and robbing strangers with impunity, and act very much with an eye to fame and posterity. I’ve compared it—online—to a sort of pre-modern Icelandic Man Bites Dog.

Read Underland by Robert Macfarlane soon after. Another book dealing in graves, more explicitly so. Grave planet.

I read We Both Laughed in Pleasure: The Selected Diaries of Lou Sullivan edited by Ellis Martin and Zach Ozma. Bought it at McNally Jackson in Williamsburg, along with a book—I Thought I Saw an Elephant!—where you poke your finger in a hole and shift an elephant cutout around the page. Lou Sullivan was a gay transgender man and an early activist working to shape a space for men like himself, and the book pulls from his diaries, beginning as a ten year old in Wisconsin, up to his AIDS related death in ‘91. The writing is great, and, joyfully, aware of it’s own skill. The entries collected deal with obsession, politics, bodies (the sex scenes are great), medicine, longing. Easily one of the best things I read this year. My colleague Cal wrote about it here and you should read that.

I read some Stephen Dixon—not strictly because he died, though he did die. Mourned him a bit with his real fans. Me, I’m an interloper. Never knew him. Haven’t read his most famous work. I read a lot of 30: Pieces of a Novel, which is Dixon in a more, I dunno, Frederick Barthelme mode? Maybe that’s a shitty comparison. Reread some of What Is All This? Uncollected Stories, which is sometimes in a more gonzo mood. That book is an amazing object, kudos to Fantagraphics.

Read my first Mark Fisher this year, too—his Capitalist Realism. I’ll work my way through more. No rush, he also died and his work won’t get any less relevant, even after we seize the means to forge a continued path for human survival on this planet.

When you’re having a very good year, books are also a kind of nesting doll signifier for all the things you know yourself to enjoy, or have built an identity performing enjoyment of—online. “Am I capable of liking things” is a fun question you end up asking yourself with every page of every book you read, during a good year. I mean to say that when I tell you I liked a book, let’s understand that to mean I recognized it as good, decouple it from affect, yes?

[millions_ad]

I read Camera by Marcelline Delbecq, translated by Emmelene Landon, very Kluge. Got that one as part of a gift from my wife, a subscription to Ugly Duckling Presse’s books in translation. One of the best gifts I’ve gotten in recent memory. Another highlight from what they sent: The Winter Garden Photograph by Cuban poet Reina Maria Rodriguez, translated by Kristin Dykstra and Nancy Gates Madsen. I’m flipping through that again right now and god these poems are so deeply satisfying, so controlled but a control that hints at the surreality at the core of all image. Like a dancer, taut, still form screaming abandon. Ha wait am I stumbling ass backward into THE DIALECTIC.

I finally read Slave Old Man by Patrick Chamoiseau, translated by Linda Coverdale. If I’d been paying attention enough to learn that it engages with the work of Edouard Glissant I’d have grabbed it sooner. I loved this book. I loved the generosity of the translation, the end notes, the structure, all of it. There is a page about midway through where the narration, switches from close third to first; I had to cover my face at the recognition of what Chamoiseau was doing there, the force of it. It’s a novel, too, in explicit conversation with Walcott.

I read Mark Haber’s wonderful and fun Reinhardt’s Garden, which is a bit Fitzcarraldo by way of Thomas Bernhard and Robert Burton. The Bernhard comparison, and what we mean when we toss that name around, is explicitly addressed in this conversation he had with Martin Riker.

I read Joao Gilberto Noll’s Lord, another fugue state narration that kind of bridges a gap—stylistically—between the Haber and the Chamoiseau. All the Noll I’ve read thus far thrums with dread, alienation, misunderstanding between character and world and reader and character, and this is no different. I’m such a fan.

Read a couple of books by other contributors to the year in reading this year. What’s the etiquette on commenting on those? Happily enough I enjoyed them both—Females by Andrea Long Chu and The Trojan War Museum and Other Stories by Ayşe Papatya Bucak. Females is that rare joy, a book that starts with a premise and works through consequences. And, too, I knew so little about Valerie Solanas going into it. What did I do in college? The Trojan War Museum I haven’t been able to get out of my head—tender and haunting.

I read The Corner That Held Them by Sylvia Townsend Warner and quickly found myself a very loud evangelist for it. This is a brilliant materialist novel that begins with a kind of "Matty Groves" scene—adultery, naked swordplay—but then immediately sends you into a convent where you follow nuns trying to find ways to pay for bridge upkeep over something like 400 pages and 300 years. This is what I want in a novel. Tell me who’s bringing the firewood and why. Who milks the cows when the black death rolls through and what happens the season after? It’s great for fans of Tuchman’s A Distant Mirror.

I read The Incompletes by Sergio Chejfec, translated by Heather Cleary. Chejfec has been the author of some of the most lasting scenes in my reading life—fleeting things: fences, muddy pathways, a bird, a stretch of track. The Incompletes revels in clue-ness, significance, but with no puzzle or expectation of an answer. Chejfec is one of the great writers of our age and this is no exception.

I read Animalia by Jean-Baptiste Del Amo, translated by Frank Wynne. It was grim and somehow—a neat trick—silent, if you know what I mean. I don’t know what I mean. Another of the best books I read this year, and a kind of answer to Zola. Ah, I see now Grove even cites Zola in their damned copy for the book. Well, it’s apt. Hi Grove. Animalia opens with a family of French peasant farmers and gets meatier and more foul over the course of decades as industrialized capitalism and mechanized death progress. It was an interesting pairing with the only Counterpoint book I’ll cite, Jean Giono’s Joy of Man’s Desiring. He’s dead, it’s fine, it’s fine to talk about this one. That novel, too, opens with a peasant farmer on a hardscrabble farm in France. In Giono’s case, though, it’s a book about rediscovering communal joy and wonder, a beautiful novel, written in ‘36 when Giono was a vocal pacifist. It’s almost a direct inverse of Del Amo’s book in every way and I far preferred Animalia. I’d be curious to hear if he’s read it and his thoughts on it.

When I read, in the span of this, the good year, I read alongside a better me, one having less of a swell time, a self who is not having and has never had a very fun year. And for every moment in which I fuzzed out or slept or hid my face beneath the cool darkness of a book just to hide, he kept reading and he felt the words. He felt them, not just the echo of when another reader might be expected to feel them. He felt them and he felt happy to feel them. What a clown.

The Millions Top Ten: July 2019

We spend plenty of time here on The Millions telling all of you what we’ve been reading, but we are also quite interested in hearing about what you’ve been reading. By looking at our Amazon stats, we can see what books Millions readers have been buying, and we decided it would be fun to use those stats to find out what books have been most popular with our readers in recent months. Below you’ll find our Millions Top Ten list for July.

This Month

Last Month

Title

On List

1.

2.

The Shell Game: Writers Play with Borrowed Forms

6 months

2.

4.

The Practicing Stoic: A Philosophical User's Manual

3 months

3.

5.

Normal People

3 months

4.

7.

The New Me

3 months

5.

6.

Educated: A Memoir

6 months

6.

10.

The Golden State

4 months

7.

9.

Slave Old Man

2 months

8.

8.

Becoming

3 months

9.

-

The Nickel Boys

1 month

10.

-

Conversations with Friends

1 month

Both Milkman by Anna Burns and Dreyer's English by Benjamin Dreyer graduated to our site's Hall of Fame this month, marking each author's first appearance on that hallowed list. Dreyer's book also becomes the first style guide to appear on a list otherwise dominated by novels, albeit interspersed with occasional rarities including at least one treatise on sharpening pencils.

Meanwhile it's heartening to see former site editor Lydia Kiesling's debut novel The Golden State ascend toward the upper-half of this month's Top Ten. The book belongs in your hands and on your shelves, but in order to get there it must first appear on our list. The higher it is, the farther it's reaching, and so on.

Newcomers on this month's list include The Nickel Boys by Colson Whitehead and Conversations with Friends by Sally Rooney. Whitehead's latest was recently featured in our Great Second-Half 2019 Book Preview, and surely it will soon be joined by additional titles on that massive list. (Have you read through it all yet?) It's also noteworthy that Rooney now has two of her books listed simultaneously on our Top Ten, an extremely rare feat around these parts.

This month’s near misses included: Selected Stories, 1968-1994 (Alice Munro), On Earth We're Briefly Gorgeous, Fever Dream, The Great Believers, and The White Card: A Play. See Also: Last month's list.

[millions_ad]

The Millions Top Ten: June 2019

We spend plenty of time here on The Millions telling all of you what we’ve been reading, but we are also quite interested in hearing about what you’ve been reading. By looking at our Amazon stats, we can see what books Millions readers have been buying, and we decided it would be fun to use those stats to find out what books have been most popular with our readers in recent months. Below you’ll find our Millions Top Ten list for June.

This Month

Last Month

Title

On List

1.

1.

Dreyer's English: An Utterly Correct Guide to Clarity and Style

6 months

2.

3.

The Shell Game: Writers Play with Borrowed Forms

5 months

3.

4.

Milkman

6 months

4.

10.

The Practicing Stoic: A Philosophical User's Manual

2 months

5.

9.

Normal People

2 months

6.

6.

Educated: A Memoir

5 months

7.

8.

The New Me

2 months

8.

7.

Becoming

2 months

9.

-

Slave Old Man

1 month

10.

-

The Golden State

3 months

This month Lydia Kiesling's The Golden State published in the United Kingdom and Australia, so it's fitting that it returns to our list. Kiesling's debut novel tracks its protagonist through some unique stresses of motherhood, but in so doing, as the author noted this week in an Australian interview, we experience the more universal stresses quite vividly:

It was my feeling when I had a very young child, as someone who reads a lot, that I hadn't really seen the minute-to-minute of care-taking portrayed on the page, and it struck me as somewhat unfair ... [In those moments] you feel like you're in some sort of epic, but one that has never really been commemorated on the page—as with going to sea, or going to war—but it can feel that big even though it's an experience that we think of as fairly mundane. That was certainly something I thought about when I sat down to write: trying to transmit some of how relentless it can feel in the moment.

Another new arrival this month is Linda Coverdale’s translation of Patrick Chamoiseau’s novel Slave Old Man, which recently won this year’s Best Translated Books Award in fiction. In an interview for our site, P.T. Smith spoke with Coverdale about her approach to translating the text:

My approach to translating has always been based on trying to make the English text reflect not just what the French says, but also what it means to native French-speakers, who are immersed—to varying degrees—in the worlds of their language, a language that has ranged widely in certain parts of the real world.

Elsewhere on this month's list, Sally Rooney's Normal People rose four spots to fifth position. This rise was so explosive it enabled her earlier novel, Conversations with Friends, to draft upwards as well, and now it ranks among this month's "near misses."

In the coming weeks, we'll publish our annual Great Book Preview, so stay tuned for shake-ups to our list after July!

This month’s near misses included: Conversations with Friends, Last Night in Nuuk, On Earth We're Briefly Gorgeous, Congo, Inc.: Bismarck's Testament, and My Sister, the Serial Killer. See Also: Last month's list.

[millions_ad]

Best Translated Book Awards Spotlight: The Millions Interviews Linda Coverdale

Linda Coverdale’s translation of Patrick Chamoiseau’s novel Slave Old Man won this year’s Best Translated Books Award in fiction. Shortly after the prize was awarded, Coverdale and I sat down to talk about Chamoiseau’s work and the importance of conveying tone and style in translated works.

The Millions: When did you first encounter this book? It’s the first work of Patrick Chamoiseau’s to be translated in over two decades. You translated him before, Creole Folktales (1995) and School Days (1996). Texaco was published in 1998. What happened then? Was he someone you wanted to continue translating, and it just wasn’t working out?

Linda Coverdale: The first Chamoiseau I ever read was Chronique des sept misères (1986), for a reader report, and I fell instantly in love with this astonishing unknown voice coming bang out of the blue, so when Carcanet Press offered to buy it if I would translate it, I was miserable saying no, but an honest translator knows when she is overmatched, and I wasn’t anywhere near ready to jump into Martinique. When the late and very great André Schiffrin offered me Au temps de l’antan (1988), however, I knew that I could begin to learn to handle both the language and the terroir with that one, so to speak. The New Press published it as Creole Folktales in 1995, and that was the first time Chamoiseau appeared in English. Baby steps in Creole-inflected text for me, with children’s stories, but they are clever tales of survival in a colonized land, already imbued with the mystique of the storyteller that colors all Chamoiseau’s writing, both in fiction and his essays. The Creole storyteller on the slave plantation becomes a secret agent in enemy territory, where his words must carry out their soul-saving mission in disguise…I started amassing my now huge stashes of books, notes, glossaries, Xeroxes of things Caribbean, all grist for the mill when the translator sets to work.

Then I moved up a notch with Chemin d’école (1994) for School Days in 1996. The word scratcher was born. He would carry his world and Creole tongue into the French empire of language while holding fast to his “inky lifeline of survival”—and he would beat the French at their own literary game. Ten years later, to my joy, the University of Nebraska gave me back that first Chamoiseau crush, Chronicle of the Seven Sorrows (1999), and I was ready: each time the bar is higher, but the terrain is more familiar, so the challenge can again be met and the beauty of the original in its humanity and wisdom can survive.

I’d read L'esclave vieil homme et le molosse when it came out in 1997 and it was breathtaking, a creation myth of such heart and purity. But it had already been bought over here, so that was that. Every once in a while I’d try to find out why it hadn’t appeared in English, but I could never learn the answer. Then The New Press returned from a buying expedition with L'empreinte à Crusoé (2012) for a reader report, but a casual remark revealed that L'Esclave vieil homme et le molosse was back in play after almost 20 years (my second second chance at a Chamoiseau treasure!), so I pounced on it. The New Press acquired it, and then the fun began.

TM: Has Chamoiseau been involved in the translations? If so, to what degree did you work together?

LC: I do sometimes contact an author, either for answers to nagging questions or—if the author speaks English—to ask what she or he thinks of the translation, and in a few cases, as with an author’s first book, we’ve worked together to remedy a few flaws in the original text, and that is always a happy experience.

Patrick Chamoiseau, however, is not only an accomplished novelist, he’s a prolific theoretician, one of the founders of the 1980’s literary movement of Créolité, and he has amply explained his views on this valorization of the Caribbean experience as a reclamation of life-affirming values imperiled by deep remnants of plantation slavery. He has famously championed the essential mystery and multivalence of his language and been sparing in his specific textual explanations, but his translators receive a basic glossary, and whenever I have contacted him, as I did with School Days and Chronicle of the Seven Sorrows, he has helped me with difficult interpretations. My m.o. has always been to do absolutely as much as I can on my own before “bothering” an author, and Chamoiseau, who is now well-known and busy in a million ways, wrote L'Esclave vieil homme et le molosse over 20 years ago.

So I definitely bless the internet: Fighting through that jungle while working on this short novel over many, many months honed my research skills to the point of tracking down even the author’s own recondite sources, and I can honestly say that at length—great length—I finally found the answers to my gazillion questions and then called it quits.

I trust that Chamoiseau is pleased to have had this novel be a finalist for a 2019 National Book Critics Circle Award and a winner of both a French-American Foundation Translation Prize and a Best Translated Books Award in 2019. And I’m delighted.

TM: What is your background with Creole, or with Martinique? It’s clear from the language, the copious notes, and your afterword that this translation is thoroughly researched, but it also feels like lived experience.

LC: My “background” with Creole is simply the love my family has had for languages and books: The idea was to read early, read widely, and read beyond your years. My parents spoke French, I learned French as a child in France, studied German on my own because my mother spoke it, studied Latin and Spanish in school, tried to learn Russian on my own, earned a doctorate in French literature, studied Italian (messed up by my Spanish), and failed risibly at Dutch (screwed up by German and English). Before the Internet took hold, I think I knew the location of every little library in New York City with a dictionary of any French Caribbean Creole, and translating works by the Haitian authors Lyonel Trouillot and René Philoctète gave me more background. I also translated the Martinican writer Raphaël Confiant, whose magisterial dictionary of Martinican Creole is itself a teaching tool of unparalleled complexity.

If you love languages, you get a feel for them and instincts that can’t be measured but which operate as if on their own, and despite the hazards of sometimes-chaotic spelling and regional variations—if you keep at it, you can track things down. I searched for the meaning of one word for months, off and on, and finally found telling clues in a Polish Ph.D. dissertation on School Days that quoted a passage including the word, and my vestigial Russian told me only that the word was an obscenity, but that was enough to dissect it into separate Martinican Creole words, allow for the optional adhesion of the definite article to a noun, in its diminutive form, and bingo: I had my word in English. Confirmed by an amused native speaker.

And NYC is full of Caribbeans: I found Martinicans delighted to help my sleuthing, even relatives of Édouard Glissant who were invaluable in their discussions of his often gnomic writings. In short, this translation was a major adventure, one that at times confounded me but in the end came out just as I had hoped.

As for the “lived” experience, I’ve often gone to the Caribbean, and over the years have been to most of the Guadeloupe Islands: Basse-Terre, Grande-Terre, Les Saintes, Marie-Galante, La Désirade, and along with the rain forests of Costa Rica in particular, they’ve been models of sensory overload: sunlight shattering through the lush tropical overstory, standing inside a massive hollow silk-cotton tree listening to the invisible life all around—these things take root, branch out into words, and imagination takes things from there.

It may seem strange, but I no longer really want to go to Martinique after all these years. I’ve grown used to the island in my mind.

[millions_ad]

TM: In addition to your afterword and endnotes, you open the book with a translator’s note. These are all valuable and interesting additions to the book, and I was happy to have them. What do you see their role as? Are they essential for a reader, or additional?

One of the things that makes Slave Old Man stand out is the original used both French and Martinican Creole. The French itself is not “standard” either, is it? In your opening note, you explain the biggest translation choice you made. The Creole is mostly left in the original, where context explains, or you use combinations, like “djok-strong.” For the most complicated words, you use the endnotes. In between is where the more unusual choice is: “once there was an old back man, a vieux-nègre, without misbehaves or gros-saut orneriness or showy ways.” So words are glossed, almost doubled. It works. It keeps the reader aware of the boundaries of Creole and French, and it fits the tone, where there is already repetition, variation, quick hits of commas, and lists. Did you consider or even try out other routes? What really made this one win for you?

LC: My approach to translating has always been based on trying to make the English text reflect not just what the French says, but also what it means to native French-speakers, who are immersed—to varying degrees—in the worlds of their language, a language that has ranged widely in certain parts of the real world. Francophone literature is dear to the French, and the writings of Marguerite Duras, for example, born and raised in French Indochina, have more dimensions in their eyes than they do in ours. Unless we do our homework. But who does, before picking up a book?

As a translator, I’m responsible for providing information encoded in the text that is, or might be, more easily accessible to a French reader, and to do that as discreetly as possible. Slave Old Man is a short but extremely complex and dense text. The creolization of the text was so widespread that it had to be maintained without disrupting the story, and frankly, you’ve already outlined the reasons why I did what I did: individual words could either remain untranslated, like gnomic little lumps in the text, or be translated into English, in which case they would simply vanish (not an option), or they would have all been translated in a huge glossary, which would have been a royal pain for the reader. Therefore, they were dealt with in situ, and as you said, this was (literally) fitting.

As for the translator’s note and endnotes, I found them necessary, but any reader is free to ignore them, although ignoring the endnotes would leave big lumps everywhere. The publisher then suggested that I add something about Chamoiseau and Glissant, and that became the afterword—again, optional, but very helpful in context. Here I might add that The New Press could not have been more supportive of my take on this translation, and dared to publish a most unusual text. Because even the “straight” French is quite like an idiolect: Chamoiseau writes in…Chamoiseau.

TM: This is a book that lives or dies on tone/style. The man at the center is a fascinating figure, but it’s the mythical tone, the unique combination of a sort of detached perspective and an immediate, pressing urgency, that makes this a special translation. A significant portion of the book is a mastiff, with an almost magical aura, chasing a slave, who is painfully human, but also already almost a legendary figure, both to other slaves and his master. Are there places in the novel, moments, lines, recurrences, that helped you lock this tone down? The full introduction of the mastiff was one for me, as a reader.

LC: Every reader reads a different story, and will react in a personal way to the text, but my interpretation is locked to the French. And that belongs to Chamoiseau. I try to match his tone, his style, and there’s no strategy to that: I try to stay out of the way. Read; write. I do have favorite moments, of course, they’re everywhere, but as an example of something modest but telling in the seismic balance of the novel, I’d cite page 13, at the end of the first chapter, where the plantation is introduced, its inhabitants sketched…and suddenly chaos sets in. For hours, the master is at a loss, cudgeling his brain, when like a Fate emerging from the shadows to announce the arrival of Destiny, “a clairvoyant négresse advances to tell him, in the sunny flash of her teeth, ‘It’s that one who’s escaped his body, oui.’” That’s it, that’s all, that is her one moment in this tale: the old slave has escaped, the master comes out of his trance—and realizes that the mastiff has been howling for hours! A howling that in Creole (défolmante) is “dis-in-te-gra-ting” the master’s world. The black crone speaks “dans l’embellie de ses dents”: an embellie, in French, is when the sun breaks through clouds, and the author uses the word five times in this tale. On page five, after announcing that the Master adores the savage mastiff because it always catches runaways, Chamoiseau tells us that “The sudden sunshine of his smile [embellie de sourire] breaks through only for this beast.” And a few pages later, we find the tables are turned, as the lowest of his slaves bares her teeth at him in a “sunny flash.” His smile, her teeth: that’s the plot in a nutshell. The second chapter now returns to the beginning, to tell the story from inside that mythical space you described. All a translator has to do is follow Chamoiseau’s lead, carefully, and it’s up to the reader to pay attention.

TM: Now, call it a spoiler if you want, but eventually, the novel switches to first person. The balance between mythical distance and realist immediacy shifts. Both elements are still there, but in a different way than before. It’s a masterful change, by both Patrick Chamoiseau and you. Even the way Creole is used after seems to be a little different. Did you find this a particular challenge, or something that came with your overall conception of the translation?

LC: Again, Chamoiseau leads, I track him, I follow. The moment when the narrative voice shifts to “I” for the runaway is dramatic, but the dog and its master are shifting as well. This book is infused with the spirit of time, and holocaust, and man’s inhumanity to man, and the heroism of great souls in surprising places, and the sacredness of art that, like the Stone, keeps life alive even in death. All the faults, injustices, oppressions, and destructions our species embodies flourish in the institution of slavery, and when the old slave breaks free to run back in time and into nature to shelter in the Stone he becomes, with all his imperfections, a lightning flash of hope, the “crystal of light” the amazed mastiff glimpses on page 90. Slave Old Man has the sublime arc of a rainbow, which leads not to a treacherous pot of gold, but to the Stone, a vision of chaos, acceptance, and redemption.

TM: Do you feel any pressure with role or responsibility translating from cultures with colonial histories like Martinique? And what should readers know about Creole and literature? Where is the movement now? This year the longlist had a book from French and Martinican Creole and one entirely from Haitian Kreyòl, Drézafi. You even discuss the latter in your note.

LC: As I said in the afterword, there is a vision of language and the world that sees the Caribbean as a self-creating model for justice and beauty, to push back against colonialism and imperialism in the widest sense. Control, exploitation, oppression—these are elements of our daily life, really, and they’re writ large in misogyny, racism, all the prejudices we harbor. I haven’t translated a single book that was all sweetness and light; six of my 80 translations were about genocide. Not including the ones about the two World Wars. My responsibility is to the French text, and as long as I’m attuned to this text, and familiar with its terrain, that takes care of everything.

That said, the extreme situation of colonialization still affects much Caribbean literature, for the local slave cultures were exclusively oral, and Chamoiseau makes no bones about his devotion to the orality and the potpourri nature of Creoles, born of the mix of African voices with the particular European language of an island’s white ruling class. His mantra: “I sacrifice everything to the music of the words.” A codicil might well be: “Screw the gaze of The Other: I wander where I please!” So did Shakespeare and Rabelais, and the more the merrier.

And Caribbean Creoles, looked at in their origins—the rubbing together of languages that create new ones—are a model of how language itself lives on. There are only 26 letters in the English alphabet, but the possibilities are infinite. I don’t teach anymore, and would never presume to speak about “Creole and literature,” but I think it’s safe to say that once-marginal voices all through our societies are speaking up, and loudly—some of them, at least—for tolerance and the opening up of all the world’s cultures, which is a welcome and wonderful thing. And we read constantly about the fading and death of languages around the globe, so any books in any Creoles are welcome saviors of the fragile worlds they sustain.

[millions_email]

And the Winners of the 2019 Best Translated Book Awards Are…

The 2019 Best Translated Book Awards were given to Slave Old Man and Of Death. Minimal Odes this evening at a ceremony at the New York Rights Fair in Manhattan.

Slave Old Man, written by Patrick Chamoiseau, translated by Linda Coverdale, and published by The New Press, won for fiction. Of Death. Minimal Odes, written by Hilda Hilst, translated by Laura Cesarco Eglin, and published by co-im-press, took the prize for poetry.

Slave Old Man is translated from the French and Creole. It is the first BTBA win for a book from the French. It is also the first victory for an author from Martinique.

Of Death. Minimal Odes is translated from the Portuguese. It is the second time poetry from Brazil has claimed the prize, after Rilke Shake won the 2016 award.

It is the first victory for both translators, and for The New Press and co-im-press. Linda Coverdale and The New Press were previously finalists for Jean Echenoz’s The Lightning.

Here is the jury’s statement on Slave Old Man:

In turns biblical and mythical, Patrick Chamoiseau’s Slave Old Man is a powerful reckoning with the agonies of the past and their persistence into the present. It is a modern epic, a history of the Caribbean, and a tribute to Creole languages, all told through the story of one slave old man. Linda Coverdale's translation sings as she beautifully renders language as lush and vividly alive as the wilderness the old man plunges into in his flight to freedom. It is dreamy yet methodical prose, vivid, sensual but also a touch strange, forcing you to slow down and reread. Thoughtful, considered footnotes provide added context and explanation, enriching the reader’s understanding of this powerful and subversive work of genius by a master storyteller. Slave Old Man is a thunderclap of a novel. His rich language, brilliant in Coverdale’s English, evokes the underground forces of resistance that carry the slave old man away. It's a novel for fugitives, and for the future.

And here's the jury statement on Of Death. Minimal Odes:

The first collection of Hilda Hilst’s poetry to be appear in English, Of Death. Minimal Odes is masterfully translated by Laura Cesarco Eglin. Hilda Hilst’s odes are searing, tender blasphemies. One is drawn to Of Death in the way we're drawn to things that might be dangerous. These are poems that lure readers well beyond their best interests, regardless of whatever scars might be sustained. In language that is twisted, animalistic, yet at times plain, Eglin reveals another layer in the work of this Brazilian great.

The fiction jury included Pierce Alquist (BookRiot), Caitlin L. Baker (Island Books), Kasia Bartoszyńska (Monmouth College), Tara Cheesman (freelance book critic), George Carroll (litintranslation.com), Adam Hetherington (reader), Keaton Patterson (Brazos Bookstore), Sofia Samatar (writer), Elijah Watson (A Room of One’s Own). The poetry jury included Jarrod Annis (Greenlight Bookstore), Katrine Øgaard Jensen (EuropeNow), Tess Lewis (writer and translator), Aditi Machado (poet and translator), and Laura Marris (writer and translator).

We announced the longlists and finalists here at the site earlier this spring.

Thanks to grant funds from the Amazon Literary Partnership, the living winning author and the translators will each receive $2,000 cash prizes. Three Percent at the University of Rochester founded the BTBAs in 2008, and since then, the Amazon Literary Partnership has contributed more than $150,000 to international authors and their translators through the BTBA. For more information, visit the official Best Translated Book Award site and the official BTBA Facebook page, and follow the award on Twitter.

[millions_ad]

Best Translated Book Awards Names 2019 Finalists

The Best Translated Books Awards today named its 2019 finalists for fiction and poetry. The award, founded by Three Percent at the University of Rochester, comes with $10,000 in prizes from the Amazon Literary Partnership.

In the past seven years, the ALP has contributed more than $150,000 to international authors and their translators through the BTBA.

This year’s BTBA finalists are as follows—and be sure to check out this year’s fiction and poetry longlists, which we announced last month.

Fiction Finalists

Congo Inc.: Bismarck’s Testament by In Koli Jean Bofane, translated from the French by Marjolijn de Jager (Democratic Republic of Congo, Indiana University Press)

The Hospital by Ahmed Bouanani, translated from the French by Lara Vergnaud (Morocco, New Directions)

Slave Old Man by Patrick Chamoiseau, translated from the French by Linda Coverdale (Martinique, New Press)

Pretty Things by Virginie Despentes, translated from the French by Emma Ramadan, (France, Feminist Press)

Moon Brow by Shahriar Mandanipour, translated from the Persian by Khalili Sara (Iran, Restless Books)

Bricks and Mortar by Clemens Meyer, translated from the German by Katy Derbyshire (Germany, Fitzcarraldo Editions)

Convenience Store Woman by Sayaka Murata, translated from the Japanese by Ginny Tapley Takemori (Japan, Grove)

The Governesses by Anne Serre, translated from the French by Mark Hutchinson (France, New Directions)

Öræfï by Ófeigur Sigurðsson, translated from the Icelandic by Lytton Smith (Iceland, Deep Vellum)

Fox by Dubravka Ugresic, translated from the Croatian by Ellen Elias-Bursac and David Williams (Croatia, Open Letter)

Poetry Finalists

The Future Has an Appointment with the Dawn by Tanella Boni, translated from the French by Todd Fredson (Cote D’Ivoire, University of Nebraska)

Moss & Silver by Jure Detela, translated from the Slovenian by Raymond Miller and Tatjana Jamnik (Slovenia, Ugly Duckling)

Of Death. Minimal Odes by Hilda Hilst, translated from the Portuguese by Laura Cesarco Eglin (Brazil, co-im-press)

Autobiography of Death by Kim Hyesoon, translated from the Korean by Don Mee Choi(Korea, New Directions)

Negative Space by Luljeta Lleshanaku, translated from the Albanian by Ani Gjika (Albania, New Directions)

The winners will be announced on Wednesday, May 29 as part of the New York Rights Fair.

[millions_ad]

Best Translated Book Awards Names 2019 Longlists

Celebrating its 12th year of honoring literature in translation, the Best Translated Book Awards named its 2019 longlists for both fiction and poetry.

Announced here—with a write-up tomorrow from BTBA founder Chad Post at Three Percent—the lists include a diverse range of authors, languages, countries, and publishers. It features familiar presses—Ugly Duckling Presse, Coffee House, New Directions—along with presses appearing for the first time, such as Song Cave and Fitzcarraldo.

Nineteen different translators are making their first appearance, while last year’s winning team of author Rodrigo Fresán and translator Will Vanderhyden returns. The lists feature authors writing in 16 different languages, from 24 different countries. The books were published by 26 different presses, the majority either independent or university presses.

Thanks to grant funds from the Amazon Literary Partnership, the winning authors and translators will each receive $5,000. The finalists for both the fiction and poetry awards will be announced on Wednesday, May 15.

Best Translated Book Award 2019: Fiction Longlist

Congo Inc.: Bismarck’s Testament by In Koli Jean Bofane, translated from the French by Marjolijn de Jager (Democratic Republic of Congo, Indiana University Press)

The Hospital by Ahmed Bouanani, translated from the French by Lara Vergnaud (Morocco, New Directions)

A Dead Rose by Aurora Cáceres, translated from the Spanish by Laura Kanost (Peru, Stockcero)

Love in the New Millennium by Xue Can, translated from the Chinese by Annelise Finegan Wasmoen (China, Yale University Press)

Slave Old Man by Patrick Chamoiseau, translated from the French by Linda Coverdale (Martinique, New Press)

Wedding Worries by Stig Dagerman, translated from the Swedish by Paul Norlen and Lo Dagerman (Sweden, David Godine)

Pretty Things by Virginie Despentes, translated from the French by Emma Ramadan, (France, Feminist Press)

Disoriental by Negar Djavadi, translated from the French by Tina Kover (Iran, Europa Editions)

Dézafi by Frankétienne, translated from the French by Asselin Charles (published by Haiti, University of Virginia Press)

Bottom of the Sky by Rodrigo Fresán, translated from the Spanish by Will Vanderhyden (Argentina, Open Letter)

Bride and Groom by Alisa Ganieva, translated from the Russian by Carol Apollonio (Russia, Deep Vellum)

People in the Room by Norah Lange, translated from the Spanish by Charlotte Whittle (Argentina, And Other Stories)

Comemadre by Roque Larraquy, translated from the Spanish by Heather Cleary (Argentina, Coffee House)

Moon Brow by Shahriar Mandanipour, translated from the Persian by Khalili Sara (Iran, Restless Books)

Bricks and Mortar by Clemens Meyer, translated from the German by Katy Derbyshire (Germany, Fitzcarraldo Editions)

Convenience Store Woman by Sayaka Murata, translated from the Japanese by Ginny Tapley Takemori (Japan, Grove)

After the Winter by Guadalupe Nettel, translated from the Spanish by Rosalind Harvey (Mexico, Coffee House)

Transparent City by Ondjaki, translated from the Portuguese by Stephen Henighan (Angola, Biblioasis)

Lion Cross Point by Masatsugo Ono, translated from the Japanese by Angus Turvill (Japan, Two Lines Press)

The Governesses by Anne Serre, translated from the French by Mark Hutchinson (France, New Directions)

Öræfï by Ófeigur Sigurðsson, translated from the Icelandic by Lytton Smith (Iceland, Deep Vellum)

Codex 1962 by Sjón, translated from the Icelandic by Victoria Cribb (Iceland, FSG)

Flights by Olga Tokarczuk, translated from the Polish by Jennifer Croft (Poland, Riverhead)

Fox by Dubravka Ugresic, translated from the Croatian by Ellen Elias-Bursac and David Williams (Croatia, Open Letter)

Seventeen by Hideo Yokoyama, translated from the Japanese by Louise Heal Kawai (Japan, FSG)

This year’s fiction jury is made up of: Pierce Alquist (BookRiot), Caitlin L. Baker (Island Books), Kasia Bartoszyńska (Monmouth College), Tara Cheesman (freelance book critic), George Carroll (litintranslation.com), Adam Hetherington (reader), Keaton Patterson (Brazos Bookstore), Sofia Samatar (writer), Ely Watson (A Room of One’s Own).

[millions_ad]

Best Translated Book Award 2019: Poetry Longlist

The Future Has an Appointment with the Dawn by Tenella Boni, translated from the French by Todd Fredson (Cote D’Ivoire, University of Nebraska)

Dying in a Mother Tongue by Roja Chamankar, translated from the Persian by Blake Atwood (Iran, University of Texas)

Moss & Silver by Jure Detela, translated from the Slovenian by Raymond Miller and Tatjana Jamnik (Slovenia, Ugly Duckling)

Of Death. Minimal Odes by Hilda Hilst, translated from the Portuguese by Laura Cesarco Eglin (Brazil, co-im-press)

Autobiography of Death by Kim Hyesoon, translated from the Korean by Don Mee Choi (Korea, New Directions)

Negative Space by Luljeta Lleshanaku, translated from the Albanian by Ani Gjika (Albania, New Directions)

Scardanelli by Frederike Mayrocker, translated from the German by Jonathan Larson (Austria, Song Cave)

the easiness and the loneliness by Asta Olivia Nordenhof, translated from the Danish by Susanna Nied (Denmark, Open Letter)

Nioque of the Early-Spring by Francis Ponge, translated from the French by Jonathan Larson (France, Song Cave)

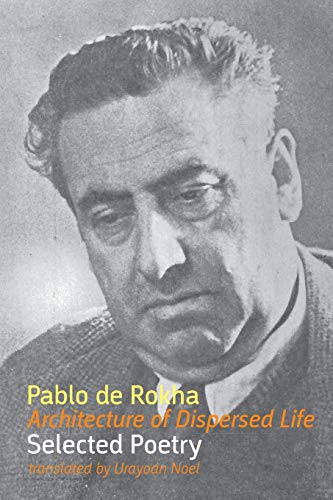

Architecture of a Dispersed Life by Pable de Rokha, translated from the Spanish by Urayoán Noel (Chile, Shearsman Books)

The poetry jury includes: Jarrod Annis (Greenlight Bookstore), Katrine Øgaard Jensen (EuropeNow), Tess Lewis (writer and translator), Aditi Machado (poet and translator), and Laura Marris (writer and translator).

For more information, visit the Best Translated Book Award site, the BTBA Facebook page, and the BTBA Twitter. And check out our coverage from 2016, 2017, and 2018.

National Book Critics Circle Award Finalists Announced

The National Book Critics Circle announced their 2018 Award Finalists, and the winners of three awards: the Ivan Sandrof Lifetime Achievement Award, John Leonard Prize, and Nona Balakian Citation for Excellence in Reviewing.

The finalists include 31 writers across six different categories: Fiction, Nonfiction, Biography, Autobiography, Fiction, Poetry, and Criticism. Here are the finalists separated by genre:

Fiction:

Milkman by Anna Burns (winner of the Man Booker Prize)

Slave Old Man by Patrick Chamoiseau (translated by Linda Coverdale)

The Largesse of the Sea Maiden by Denis Johnson

The Mars Room by Rachel Kushner

The House of Broken Angels by Luis Alberto Urrea

Nonfiction:

The Line Becomes a River: Dispatches from the Border by Francisco Cantú (part of our 2018 Great Book Preview)

Directorate S: The C.I.A. and America’s Secret Wars in Afghanistan and Pakistan by Steve Coll

The Coddling of the American Mind: How Good Intentions and Bad Ideas Are Setting Up a Generation for Failure by Greg Lukianoff and Jonathan Haidt

We the Corporations: How American Businesses Won Their Civil Rights by Adam Winkler