Mentioned in:

A Year in Reading: 2024

Welcome to the 20th (!) installment of The Millions' annual Year in Reading series, which gathers together some of today's most exciting writers and thinkers to share the books that shaped their year. YIR is not a collection of yearend best-of lists; think of it, perhaps, as an assemblage of annotated bibliographies. We've invited contributors to reflect on the books they read this year—an intentionally vague prompt—and encouraged them to approach the assignment however they choose.

In writing about our reading lives, as YIR contributors are asked to do, we inevitably write about our personal lives, our inner lives. This year, a number of contributors read their way through profound grief and serious illness, through new parenthood and cross-country moves. Some found escape in frothy romances, mooring in works of theology, comfort in ancient epic poetry. More than one turned to the wisdom of Ursula K. Le Guin. Many describe a book finding them just when they needed it.

Interpretations of the assignment were wonderfully varied. One contributor, a music critic, considered the musical analogs to the books she read, while another mapped her reads from this year onto constellations. Most people's reading was guided purely by pleasure, or else a desire to better understand events unfolding in their lives or larger the world. Yet others centered their reading around a certain sense of duty: this year one contributor committed to finishing the six Philip Roth novels he had yet to read, an undertaking that he likens to “eating a six-pack of paper towels.” (Lucky for us, he included in his essay his final ranking of Roth's oeuvre.)

The books that populate these essays range widely, though the most commonly noted title this year was Tony Tulathimutte’s story collection Rejection. The work of newly minted National Book Award winner Percival Everett, particularly his acclaimed novel James, was also widely read and written about. And as the genocide of Palestinians in Gaza enters its second year, many contributors sought out Isabella Hammad’s searing, clear-eyed essay Recognizing the Stranger.

Like so many endeavors in our chronically under-resourced literary community, Year in Reading is a labor of love. The Millions is a one-person editorial operation (with an invaluable assist from SEO maven Dani Fishman), and producing YIR—and witnessing the joy it brings contributors and readers alike—has been the highlight of my tenure as editor. I’m profoundly grateful for the generosity of this year’s contributors, whose names and entries will be revealed below over the next three weeks, concluding on Wednesday, December 18. Be sure to subscribe to The Millions’ free newsletter to get the week’s entries sent straight to your inbox each Friday.

—Sophia Stewart, editor

Becca Rothfeld, author of All Things Are Too Small

Carvell Wallace, author of Another Word for Love

Charlotte Shane, author of An Honest Woman

Brianna Di Monda, writer and editor

Nell Irvin Painter, author of I Just Keep Talking

Carrie Courogen, author of Miss May Does Not Exist

Ayşegül Savaş, author of The Anthropologists

Zachary Issenberg, writer

Tony Tulathimutte, author of Rejection

Ann Powers, author of Traveling: On the Path of Joni Mitchell

Lidia Yuknavitch, author of Reading the Waves

Nicholas Russell, writer and critic

Daniel Saldaña París, author of Planes Flying Over a Monster

Lili Anolik, author of Didion and Babitz

Deborah Ghim, editor

Emily Witt, author of Health and Safety

Nathan Thrall, author of A Day in the Life of Abed Salama

Lena Moses-Schmitt, author of True Mistakes

Jeremy Gordon, author of See Friendship

John Lee Clark, author of Touch the Future

Ellen Wayland-Smith, author of The Science of Last Things

Edwin Frank, publisher and author of Stranger Than Fiction

Sophia Stewart, editor of The Millions

A Year in Reading Archives: 2023, 2022, 2021, 2020, 2019, 2018, 2017, 2016, 2015, 2014, 2013, 2011, 2010, 2009, 2008, 2007, 2006, 2005

The Great Fall 2024 Book Preview

With the arrival of autumn comes a deluge of great books. Here you'll find a sampling of new and forthcoming titles that caught our eye here at The Millions, and that we think might catch yours, too. Some we’ve already perused in galley form; others we’re eager to devour based on their authors, plots, or subject matters. We hope your next fall read is among them.

—Sophia Stewart, editor

October

Season of the Swamp by Yuri Herrera, tr. Lisa Dillman [F]

What it is: An epic, speculative account of the 18 months that Benito Juárez spent in New Orleans in 1853-54, years before he became the first and only Indigenous president of Mexico.

Who it's for: Fans of speculative history; readers who appreciate the magic that swirls around any novel set in New Orleans. —Claire Kirch

The Black Utopians by Aaron Robertson [NF]

What it is: An exploration of Black Americans' pursuit and visions of utopia—both ideological and physical—that spans the Reconstruction era to the present day and combines history, memoir, and reportage.

Who it's for: Fans of Saidiya Hartman's Wayward Lives, Beautiful Experiments and Kristen R. Ghodsee's Everyday Utopia. —Sophia M. Stewart

The Third Realm by Karl Ove Knausgaard, tr. Martin Aitken [F]

What it is: The third installment in Knausgaard's Morning Star series, centered on the appearance of a mysterious new star in the skies above Norway.

Who it's for: Real Knausgaard heads only—The Wolves of Eternity and Morning Star are required reading for this one. —SMS

Brown Women Have Everything by Sayantani Dasgupta [NF]

What it is: Essays on the contradictions and complexities of life as an Indian woman in America, probing everything from hair to family to the joys of travel.

Who it's for: Readers of Durga Chew-Bose, Erika L. Sánchez, and Tajja Isen. —SMS

The Plot Against Native America by Bill Vaughn [F]

What it is: The first narrative history of Native American boarding schools— which aimed "civilize" Indigenous children by violently severing them from their culture— and their enduring, horrifying legacy.

Who it's for: Readers of Ned Blackhawk and Kathleen DuVal. —SMS

The Mighty Red by Louise Erdrich [F]

What it is: Erdrich's latest novel set in North Dakota's Red River Valley is a tale of the intertwined lives of ordinary people striving to survive and even thrive in their rural community, despite environmental upheavals, the 2008 financial crisis, and other obstacles.

Who it's for: Readers of cli-fi; fans of Linda LeGarde Grover and William Faulkner. —CK

The Position of Spoons by Deborah Levy [NF]

What it is: The second book from Levy in as many years, diverging from a recent streak of surrealist fiction with a collection of essays marked by exceptional observance and style.

Who it's for: Close lookers and the perennially curious. —John H. Maher

The Bog Wife by Kay Chronister [F]

What it's about: The Haddesley family has lived on the same West Virginia bog for centuries, making a supernatural bargain with the land—a generational blood sacrifice—in order to do so—until an uncovered secret changes everything.

Who it's for: Readers of Karen Russell and Jeff VanderMeer; anyone who has ever used the phrase "girl moss." —SMS

The Great When by Alan Moore [F]

What it's about: When an 18-year old book reseller comes across a copy of a book that shouldn’t exist, it threatens to upend not just an already post-war-torn London, but reality as we know it.

Who it's for: Anyone looking for a Sherlock Holmes-style mystery dipped in thaumaturgical psychedelia. —Daniella Fishman

The Message by Ta-Nehisi Coates [NF]

What it's about: One of our sharpest critical thinkers on social justice returns to nonfiction, nearly a decade after Between the World and Me, visiting Dakar, to contemplate enslavement and the Middle Passage; Columbia, S.C., as a backdrop for his thoughts on Jim Crow and book bans; and the Israeli-occupied West Bank, where he sees contemporary segregation in the treatment of Palestinians.

Who it’s for: Fans of James Baldwin, George Orwell, and Angela Y. Davis; readers of Nikole Hannah-Jones’s The 1619 Project and Isabel Wilkerson’s Caste, to name just a few engagements with national and racial identity. —Nathalie op de Beeck

Abortion by Jessica Valenti [NF]

What it is: Columnist and memoirist Valenti, who tracks pro-choice advocacy and attacks on the right to choose in her Substack, channels feminist rage into a guide for freedom of choice advocacy.

Who it’s for: Readers of Robin Marty’s The New Handbook for a Post-Roe America, #ShoutYourAbortion proponents, and followers of Jennifer Baumgartner’s [I Had an Abortion] project. —NodB

Gifted by Suzuki Suzumi, tr. Allison Markin Powell [F]

What it's about: A young sex worker in Tokyo's red-light district muses on her life and recounts her abusive mother's final days, in what is Suzuki's first novel to be translated into English.

Who it's for: Readers of Susan Boyt and Mieko Kanai; fans of moody, introspective fiction; anyone with a fraught relationship to their mother. —SMS

Childish Literature by Alejandro Zambra, tr. Megan McDowell [F]

What it is: A wide-ranging collection of stories, essays, and poems that explore childhood, fatherhood, and family.

Who it's for: Fans of dad lit (see: Lucas Mann's Attachments, Keith Gessen's Raising Raffi, Karl Ove Knausgaard's seasons quartet, et al). —SMS

Books Are Made Out of Books ed. Michael Lynn Crews [NF]

What it is: A mining of the archives of the late Cormac McCarthy with a focus on the famously tight-lipped author's literary influences.

Who it's for: Anyone whose commonplace book contains the words "arquebus," "cordillera," or "vinegaroon." —JHM

Slaveroad by John Edgar Wideman [F]

What it is: A blend of memoir, fiction, and history that charts the "slaveroad" that runs through American history, spanning the Atlantic slave trade to the criminal justice system, from the celebrated author of Brothers and Keepers.

Who it's for: Fans of Clint Smith and Ta-Nehisi Coates. —SMS

Linguaphile by Julie Sedivy [NF]

What it's about: Linguist Sedivy reflects on a life spent loving language—its beauty, its mystery, and the essential role it plays in human existence.

Who it's for: Amateur (or professional) linguists; fans of the podcast A Way with Words (me). —SMS

An Image of My Name Enters America by Lucy Ives [NF]

What it is: A collection of interrelated essays that connect moments from Ives's life to larger questions of history, identity, and national fantasy,

Who it's for: Fans of Ives, one of our weirdest and most wondrous living writers—duh; anyone with a passing interest in My Little Pony, Cold War–era musicals, or The Three Body Problem, all of which are mined here for great effect. —SMS

Women's Hotel by Daniel Lavery [F]

What it is: A novel set in 1960s New York City, about the adventures of the residents of a hotel providing housing for young women that is very much evocative of the real-life legendary Barbizon Hotel.

Who it's for: Readers of Mary McCarthy's The Group and Rona Jaffe's The Best of Everything. —CK

The World in Books by Kenneth C. Davis [NF]

What it is: A guide to 52 of the most influential works of nonfiction ever published, spanning works from Plato to Ida B. Wells, bell hooks to Barbara Ehrenreich, and Sun Tzu to Joan Didion.

Who it's for: Lovers of nonfiction looking to cover their canonical bases. —SMS

Blue Light Hours by Bruna Dantas Lobato [F]

What it's about: Through the emanating blue-glow of their computer screens, a mother and daughter, four-thousand miles apart, find solace and loneliness in their nightly Skype chats in this heartstring-pulling debut.

Who it's for: Someone who needs to be reminded to CALL YOUR MOTHER! —DF

Riding Like the Wind by Iris Jamahl Dunkle [NF]

What it is: The biography of Sanora Babb, a contemporary of John Steinbeck's whose field notes and interviews with Dust Bowl migrants Steinbeck relied upon to write The Grapes of Wrath.

Who it's for: Steinbeck fans and haters alike; readers of Kristin Hannah's The Four Winds and the New York Times Overlooked column; anyone interested in learning more about the Dust Bowl migrants who fled to California hoping for a better life. —CK

Innie Shadows by Olivia M. Coetzee [F]

What it is: a work of crime fiction set on the outskirts of Cape Town, where a community marred by violence seeks justice and connection; also the first novel to be translated from Kaaps, a dialect of Afrikaans that was until recently only a spoken language.

Who it's for: fans of sprawling, socioeconomically-attuned crime dramas a la The Wire. —SMS

Dorothy Parker in Hollywood by Gail Crowther [NF]

What it is: A history of the famous wit—and famous New Yorker—in her L.A. era, post–Algonquin Round Table and mid–Red Scare.

Who it's for: Owners of a stack of hopelessly dog-eared Joan Didion paperbacks. —JHM

The Myth of American Idealism by Noam Chomsky and Nathan J. Robinson [NF]

What it is: A potent critique of the ideology behind America's foreign interventions and its status as a global power, and an treatise on how the nation's hubristic pursuit of "spreading democracy" threatens not only the delicate balance of global peace, but the already-declining health of our planet.

Who it's for: Chomskyites; policy wonks and casual critics of American recklessness alike. —DF

Mysticism by Simon Critchley [NF]

What it is: A study of mysticism—defined as an experience, rather than religious practice—by the great British philosopher Critchley, who mines music, poetry, and literature along the way.

Who it's for: Readers of John Gray, Jorge Luis Borges, and Simone Weil. —SMS

Q&A by Adrian Tomine [NF]

What it is: The Japanese American creator of the Optic Nerve comic book series for D&Q, and of many a New Yorker cover, shares his personal history and his creative process in this illustrated unburdening.

Who it’s for: Readers of Tomine’s melancholic, sometimes cringey, and occasionally brutal collections of comics short stories including Summer Blonde, Shortcomings, and Killing and Dying. —NodB

Sonny Boy by Al Pacino [NF]

What it is: Al Pacino's memoir—end of description.

Who it's for: Cinephiles; anyone curious how he's gonna spin fumbling Diane Keaton. —SMS

Seeing Baya by Alice Kaplan [NF]

What it is: The first biography of the enigmatic and largely-forgotten Algerian artist Baya Mahieddine, who first enchanted midcentury Paris as a teenager.

Who it's for: Admirers of Leonora Carrington, Hilma af Klint, Frida Kahlo, and other belatedly-celebrated women painters. —SMS

Absolution by Jeff VanderMeer [F]

What it is: A surprise return to the Area X, the stretch of unforbidding and uncanny coastline in the hit Southern Reach trilogy.

Who it's for: Anyone who's heard this song and got the reference without Googling it. —JHM

The Four Horsemen by Nick Curtola [NF]

What it is: The much-anticipated cookbook from the team behind Brooklyn's hottest restaurant (which also happens to be co-owned by James Murphy of LCD Soundsystem).

Who it's for: Oenophiles; thirty-somethings who live in north Williamsburg (derogatory). —SMS

Seeing Further by Esther Kinsky, tr. Caroline Schmidt [F]

What it's about: An unnamed German woman embarks on the colossal task of reviving a cinema in a small Hungarian village.

Who it's for: Fans of Jenny Erpenbeck; anyone charmed by Cinema Paradiso (not derogatory!). —SMS

Ripcord by Nate Lippens [NF]

What it's about: A novel of class, sex, friendship, and queer intimacy, written in delicious prose and narrated by a gay man adrift in Milwaukee.

Who it's for: Fans of Brontez Purnell, Garth Greenwell, Alexander Chee, and Wayne Koestenbaum. —SMS

The Use of Photography by Annie Ernaux and Marc Marie, tr. Alison L. Strayer [NF]

What it's about: Ernaux's love affair with Marie, a journalist, while she was undergoing treatment for cancer, and their joint project to document their romance.

Who it's for: The Ernaux hive, obviously; readers of Sontag's On Photography and Janet Malcolm's Still Pictures. —SMS

Nora Ephron at the Movies by Ilana Kaplan [NF]

What it is: Kaplan revisits Nora Ephron's cinematic watersheds—Silkwood, Heartburn, When Harry Met Sally, You've Got Mail, and Sleepless in Seattle—in this illustrated book. Have these iconic stories, and Ephron’s humor, weathered more than 40 years?

Who it’s for: Film history buffs who don’t mind a heteronormative HEA; listeners of the Hot and Bothered podcast; your coastal grandma. —NodB

[millions_email]

The Philosophy of Translation by Damion Searls [NF]

What it is: A meditation on the act and art of translation by one of today's most acclaimed practitioners, best known for his translations of Fosse, Proust, et al.

Who it's for: Regular readers of Words Without Borders and Asymptote; professional and amateur literary translators alike. —SMS

Salvage by Dionne Brand

What it is: A penetrating reevaluation of the British literary canon and the tropes once shaped Brand's reading life and sense of self—and Brand’s first major work of nonfiction since her landmark A Map to the Door of No Return.

Who it's for: Readers of Christina Sharpe's Ordinary Notes and Elizabeth Hardwick's Seduction and Betrayal. —SMS

Masquerade by Mike Fu [F]

What it's about: Housesitting for an artist friend in present-day New York, Meadow Liu stumbles on a novel whose author shares his name—the first of many strange, haunting happenings that lead up to the mysterious disappearance of Meadow's friend.

Who it's for: fans of Ed Park and Alexander Chee. —SMS

November

The Beggar Student by Osamu Dazai, tr. Sam Bett [F]

What it is: A novella in the moody vein of Dazai’s acclaimed No Longer Human, following the 30-something “fictional” Dazai into another misadventure spawned from a hubristic spat with a high schooler.

Who it's for: Longtime readers of Dazai, or new fans who discovered the midcentury Japanese novelist via TikTok and the Bungo Stray Dogs anime. —DF

In Thrall by Jane DeLynn [F]

What it is: A landmark lesbian bildungsroman about 16-year-old Lynn's love affair with her English teacher, originally published in 1982.

Who it's for: Fans of Joanna Russ's On Strike Against God and Edmund White's A Boy's Own Story —SMS

Washita Love Child by Douglas Kent Miller [NF]

What it is: The story of Jesse Ed Davis, the Indigenous musician who became on of the most sought after guitarists of the late '60s and '70s, playing alongside B.B. King, Bob Dylan, John Lennon, and more.

Who it's for: readers of music history and/or Indigenous history; fans of Joy Harjo, who wrote the foreword. —SMS

Set My Heart on Fire by Izumi Suzuki, tr. Helen O'Horan [F]

What it is: Gritty, sexy, and wholly rock ’n’ roll, Suzuki’s first novel translated into English (following her story collection, Hit Parade of Tears) follows 20-year-old Izumi navigating life, love, and music in the underground scene in '70s Japan.

Who it's for: Fans of Meiko Kawakami, Ursula K. Le Guin, and Marlowe Granados's Happy Hour. —DF

Didion & Babitz by Lili Anolik [NF]

What it is: A dual portrait of Joan Didion and Eve Babitz, who are so often compared to—and pitted against—each other on the basis of their mutual Los Angeles milieu.

Who it's for: Fans or haters of either writer (the book is fairly pro-Babitz, often at Didion's expense); anyone who has the Lit Hub Didion tote bag. —SMS

The Endless Refrain by David Rowell [NF]

What it's about: How the rise of music streaming, demonitizing of artist revenue, and industry tendency toward nostalgia have laid waste to the musical landscape, and the future of music culture.

Who it's for: Fans of Kyle Chayka, Spence Kornhaber, and Lindsay Zoladz. —SMS

Every Arc Bends Its Radian by Sergio De La Pava [F]

What it is: A mind- and genre-bending detective story set in Cali, Colombia, that blends high-stakes suspense with rigorous philosophy.

Who it's for: Readers of Raymond Chandler, Thomas Pynchon, and Jules Verne. —SMS

Something Close to Nothing by Tom Pyun [F]

What it’s about: At the airport with his white husband Jared, awaiting a flight to Cambodia to meet the surrogate mother carrying their adoptive child-to-be, Korean American Wynn decides parenthood isn't for him, and bad behavior ensues.

Who it’s for: Pyun’s debut is calculated to cut through saccharine depictions of queer parenthood—could pair well with Torrey Peters’s Detransition, Baby. —NodB

Rosenfeld by Maya Kessler [F]

What it is: Kessler's debut—rated R for Rosenfeld—follows one Noa Simmons through the tumultuous and ultimately profound power play that is courting (and having a lot of sex with) the titular older man who soon becomes her boss.

Who it's for: Fans of Sex and the City, Raven Leilani’s Luster, and Coco Mellor’s Cleopatra and Frankenstein. —DF

Lazarus Man by Richard Price [F]

What it is: The former The Wire writer offers yet another astute chronicle of urban life, this time of an ever-changing Harlem.

Who it's for: Fans of Colson Whitehead's Crook Manifesto and Paul Murray's The Bee Sting—and, of course, The Wire. —SMS

Stranger Than Fiction by Edwin Frank [NF]

What it is: An astute curveball of a read on the development and many manifestations of the novel throughout the tumultuous 20th century.

Who it's for: Readers who look at a book's colophon before its title. —JHM

Letters to His Neighbor by Marcel Proust, tr. Lydia Davis

What it is: A collection of Proust’s tormented—and frequently hilarious—letters to his noisy neighbor which, in a diligent translation from Davis, stand the test of time.

Who it's for: Proust lovers; people who live below heavy-steppers. —DF

Context Collapse by Ryan Ruby [NF]

What it is: A self-proclaimed "poem containing a history of poetry," from ancient Greece to the Iowa Workshop, from your favorite literary critic's favorite literary critic.

Who it's for: Anyone who read and admired Ruby's titanic 2022 essay on The Waste Land; lovers of poetry looking for a challenge. —SMS

How Sondheim Can Change Your Life by Richard Schoch [NF]

What it's about: Drama professor Schoch's tribute to Stephen Sondheim and the life lessons to be gleaned from his music.

Who it's for: Sondheim heads, former theater kids, end of list. —SMS

The Serviceberry by Robin Wall Kimmerer [NF]

What it is: 2022 MacArthur fellow and botanist Kimmerer, an enrolled member of the Citizen Potawatomi Nation, (re)introduces audiences to a flowering, fruiting native plant beloved of foragers and gardeners.

Who it’s for: The restoration ecologist in your life, along with anyone who loved Braiding Sweetgrass and needs a nature-themed holiday gift. —NodB

My Heart Belongs in an Empty Big Mac Container Buried Beneath the Ocean Floor by Homeless [F]

What it is: A pseudonymous, tenderly comic novel of blue whales and Golden Arches, mental illness and recovery.

Who it's for: Anyone who finds Thomas Pynchon a bit too staid. —JHM

Yoke and Feather by Jessie van Eerden [NF]

What it's about: Van Eerden's braided essays explore the "everyday sacred" to tease out connections between ancient myth and contemporary life.

Who it's for: Readers of Courtney Zoffness's Spilt Milk and Jeanna Kadlec's Heretic. —SMS

Camp Jeff by Tova Reich [F]

What it's about: A "reeducation" center for sex pests in the Catskills, founded by one Jeffery Epstein (no, not that one), where the dual phenomena of #MeToo and therapyspeak collide.

Who it's for: Fans of Philip Roth and Nathan Englander; cancel culture skeptics. —SMS

Selected Amazon Reviews by Kevin Killian [NF]

What it is: A collection of 16 years of Killian’s funniest, wittiest, and most poetic Amazon reviews, the sheer number of which helped him earn the rarefied “Top 100” and “Hall of Fame” status on the site.

Who it's for: Fans of Wayne Koestenbaum and Dodie Bellamy, who wrote introduction and afterword, respectively; people who actually leave Amazon reviews. —DF

Cher by Cher [NF]

What it is: The first in a two-volume memoir, telling the story of Cher's early life and ascendent career as only she can tell it.

Who it's for: Anyone looking to fill the My Name Is Barbra–sized hole in their heart, or looking for something to tide them over until the Liza memoir drops. —SMS

The City and Its Uncertain Walls by Haruki Murakami, tr. Philip Gabriel [F]

What it is: Murakami’s first novel in over six years returns to the high-walled city from his 1985 story "Hard-Boiled Wonderland and the End of the World" with one man's search for his lost love—and, simultaneously, an ode to libraries and literature itself.

Who it's for: Murakami fans who have long awaited his return to fiction. —DF

American Bulk by Emily Mester [NF]

What it's about: Reflecting on what it means to "live life to the fullest," Mester explores the cultural and personal impacts of America’s culture of overconsumption, from Costco hauls to hoarding to diet culture—oh my!

Who it's for: Lovers of sustainability; haters of excess; skeptics of the title essay of Becca Rothfeld's All Things Are Too Small. —DF

The Icon and the Idealist by Stephanie Gorton [NF]

What it is: A compelling look at the rivalry between Margaret Sanger, of Planned Parenthood fame, and Mary Ware Dennett, who each held radically different visions for the future of birth control.

Who it's for: Readers of Amy Sohn's The Man Who Hated Women and Katherine Turk's The Women of NOW; anyone interested in the history of reproductive rights. —SMS

December

Rental House by Weike Wang [F]

What it's about: Married college sweethearts invite their drastically different families on a Cape Code vacation, raising questions about marriage, intimacy, and kinship.

Who it's for: Fans of Wang's trademark wit and sly humor (see: Joan Is Okay and Chemistry); anyone with an in-law problem.

Woo Woo by Ella Baxter [F]

What it's about: A neurotic conceptual artist loses her shit in the months leading up to an exhibition that she hopes will be her big breakout, poking fun at the tropes of the "art monster" and the "woman of the verge" in one fell, stylish swoop.

Who it's for: Readers of Sheena Patel's I'm a Fan and Chris Kraus's I Love Dick; any woman who is grateful to but now also sort of begrudges Jenny Offil for introducing "art monster" into the lexicon (me). —SMS

Berlin Atomized by Julia Kornberg, tr. Jack Rockwell and Julia Kornberg [F]

What it's about: Spanning 2001 to 2034, three Jewish and downwardly mobile siblings come of age in various corners of the world against the backdrop of global crisis.

Who it's for: Fans of Catherine Lacey's Biography of X and Joshua Cohen's The Netanyahus. —SMS

Sand-Catcher by Omar Khalifah, tr. Barbara Romaine [F]

What it is: A suspenseful, dark satire of memory and nation, in which four young Palestinian journalists at a Jordanian newspaper are assigned to interview an elderly witness to the Nakba, the violent 1948 expulsion of native Palestinians from Israel—but to their surprise, the survivor doesn’t want to rehash his trauma for the media.

Who it’s for: Anyone looking insight—tinged with grim humor—into the years leading up to the present political crisis in the Middle East and the decades-long goal of Palestinian autonomy. —NodB

The Shutouts by Gabrielle Korn [F]

What it's about: In the dystopian future, mysteriously connected women fight to survive on the margins of society amid worsening climate collapse.

Who it's for: Fans of Korn's Yours for the Taking, which takes place in the same universe; readers of Becky Chambers and queer-inflected sci-fi. —SMS

What in Me Is Dark by Orlando Reade [NF]

What it's about: The enduring, evolving influence of Milton's Paradise Lost on political history—and particularly on the work of 12 revolutionary readers, including Malcom X and Hannah Arendt.

Who it's for: English majors and fans of Ryan Ruby and Sarah Bakewell—but I repeat myself. —SMS

The Afterlife Is Letting Go by Brandon Shimoda [NF]

What it's about: Shimoda researches the mass incarceration of Japanese Americans during WWII, and speaks with descendants of those imprisoned, for this essay collection about the “afterlife” of cruelty and xenophobia in the U.S.

Who it’s for: Anyone to ever visit a monument, museum, or designated site of hallowed ground where traumatic events have taken place. —NodB

No Place to Bury the Dead by Karina Sainz Borgo, tr. Elizabeth Bryer [F]

What it's about: When Angustias Romero loses both her children while fleeing a mysterious disease in her unnamed Latin American country, she finds herself in a surreal, purgatorial borderland where she's soon caught in a power struggle.

Who it's for: Fans of Maríana Enriquez and Mohsin Hamid. —SMS

The Rest Is Silence by Augusto Monterroso, tr. Aaron Kerner [F]

What it is: The author of some of the shortest, and tightest, stories in Latin American literature goes long with a metafictional skewering of literary criticism in his only novel.

Who it's for: Anyone who prefers the term "palm-of-the-hand stories" to "flash fiction." —JHM

Tali Girls by Siamak Herawi, tr. Sara Khalili [F]

What it is: An intimate, harrowing, and vital look at the lives of girls and women in an Afghan mountain village under Taliban rule, based on true stories.

Who it's for: Readers of Nadia Hashimi, Akwaeke Emezi, and Maria Stepanova. —SMS

Sun City by Tove Jansson, tr. Thomas Teal [F]

What it's about: During her travels through the U.S. in the 1970s, Jansson became interested in the retirement home as a peculiarly American institution—here, she imagines the tightly knit community within one of them.

Who it's for: Fans of Jansson's other fiction for adults, much of which explores the lives of elderly folks; anyone who watched that documentary about The Villages in Florida. —SMS

Editor's note: We're always looking to make our seasonal book previews more useful to the readers, writers, and critics they're meant to serve. Got an idea for how we can improve our coverage? Tell me about it at sophia@themillions.com.

[millions_email]

Genuinely Weird

Jeff Vandermeer's Southern Reach trilogy: a genuinely weird work of ecological fiction, a hyper-object, or a strangely beautiful "glimpse of a whole that’s, by its nature, unknowable"? Joshua Rothman argues for all three in a review for The New Yorker. For more from Vandermeer himself, check out his Millions interview with Richard House, author of The Kills.

More Stark Than Bleak: The Millions Interviews Richard House

For me, the best read of 2014 was Richard House’s thousand-page hardcover The Kills. I traveled a lot last year and I lugged The Kills around with me everywhere, undaunted by the fact that it was not built for shoving into an airplane seat-back pocket. It was the tome I could not put down, and it captured me so utterly that I begged off meal invites and bar get-togethers to finish it. I resented gigs because if I was reading my own work I wasn’t reading The Kills.

The Kills begins with a classic set-up: embezzled money, predatory contractors, and illegal U.S. waste burning sites in the Iraqi desert. A character known as “Sutler” (not his real name) serves as the front for a much larger conspiracy. From the literal and figurative wreckage of secret machinations, the novel explodes outward, exploring every bit of shrapnel and collateral damage, every consequence of the initial corruption. As Sutler flees the scene, other characters come into focus and then disappear into the anonymity from whence they came. Identities are abandoned, replaced with new fictions and mythologies about the self. The soldiers in charge of the burn pit reappear in a different context later in the novel. A book about serial killers in Italy -- based on real events? -- permeates all four sections and influences decisions by the soldiers back in civilian life.

House gives the reader exactly what we need to know about each character and situation through deft shifting between points of view, but no more than that. The overall structure has immense power as a result, thwarting normal reader expectations while showing great respect for the reader’s imagination. Comparisons to Thomas Pynchon, John le Carré, and Roberto Bolaño apply, but really are only a way of letting readers know the general territory they’re about to traverse. In short, the novel is surprising and unique -- and, in the end, cathartic.

Published in the U.K. in 2013, The Kills was long-listed for the Man Booker Prize. It’s been highly lauded, and House, an accomplished filmmaker, has created audio/video extras that further illuminate the story. I interviewed House recently via email to explore some of the ideas in The Kills.

Jeff VanderMeer: In what ways does fiction infiltrate history? And, as individuals, are we fated to turn life into a story of some kind, whether we mean to or not? Is this different for U.K. writers?

Richard House: There's a cultural difference in what happens in the U.S., the U.K., and Europe -- in how writers do and don't directly address social issues. I don't want to generalise, but I do think U.S. writers allow themselves a broader platform in terms of subject, and also in how they approach form. It's engaged and also playful. I've a lot of respect for that.

On a more fundamental level we (as in a generic 'we,' not just writers) have bad habits when it comes to translating life into any kind of narrative. I think this is almost automatic -- and I really want to resist this -- the way that fictive structures begin to shape and command history. The sense that events have a beginning, a middle, and an end is pernicious. It's so deep we rarely question it. For me it comes from the way I was taught at school, from the way the media shape events, and even from the way my parents and peers speak about the world. There's an artificiality to all of these stories, because they are always complete, and lessons are always learned. There's always a point. I find this notion of closure really dangerous and it works against my experience of the world, of history -- there's a sense of putting something away, of learning from it, and of trying to establish one dominant way of regard. As if what we go through has a design, so that something occurs in the world for the explicit purpose of teaching us something, or proving a point. I find this artificial and frightening. It's a form of consumption. It's also, essentially, lazy. That three-part structure oversimplifies everything. I dislike the transformation of life or events into a received three-part act with an intensity.

That said, I think fiction is a useful, perhaps the most useful, way to digest the world, to consider ideas and positions that you otherwise couldn't enter so willingly or freely -- and fiction, like all disciplines, has certain necessary defining structures, genre to genre. Plus, it's almost impossible not to narrate the world in some way, which is all about finding your feet, I suppose. I prefer fiction which struggles with topical events and wrestles with how to tell them -- and that often comes through the lens of a specific genre.

JV: I don't think of you as an absurdist in the way Franz Kafka was, but there is a streak of the irrational running through The Kills that struck me as very true to the way the world works. Where does this come from? I'm curious about your personal entry point or observation platform.

RH: For me this is a structural thing also. I want to resist that desire to round off, to teach, to give across an explicit position. In fiction there's enough space to allow a reader to construct their own story. That roughness, of one thing knocking into another, is for me, pretty much how the world works.

I'm 53 and too much of a pragmatist to be truly absurd (although I've a weakness for humour which tends toward the absurd). Experience very rarely matches expectation (usually a very good thing, sometimes just awful) because at any given time the story or event which you think will play out in certain way, just isn't the same story or event to anyone else. Experience is always oddly articulated -- seldom ever what you expect. Things collide. Our perspectives are intimately subjective, and therefore always skewed. The good thing is that we're not alone in this. Everyone bumps along, one way or another, all at different speeds. Most of the time there's a sense that this or that is under our control, but that can fluctuate in a nano-second depending on a million other things. This goes back to your first question, how the world as we speak about it isn't really the world that we experience.

JV: Are there parts of the novel you meant to be darkly funny?

RH: Definitely. Some of the core ideas -- like building a city in the middle of nowhere -- are to me rich with potential. I try to level that darker stuff as it can dominate -- more stark than bleak, I guess. I particularly enjoyed writing the sections with Rem in Iraq, it's not that these sections are funny, so much, but I liked writing about how men congregate, socialise, wrestle for position. Similarly with characters like Rike and her sister, there's a competition and friendship that I hope comes through with a little more lightness than in other sections. There's a wryness to the German Berens also. I've known many people like that who seem to closely observe themselves. In person I'm a lot more affable than my writing probably indicates.

JV: The section entitled "The Kill" and set in Italy is, to me, the center of the novel thematically and it radiates out fictional affects that impact the real world. There's a potential resonance or connection with the parts set in Iraq in the depictions of war-time life as well. Were there other, less obvious connections, you want the reader to make?

RH: As I worked on the main body of The Kills, the idea that there would be a separate story which would somehow refocus ideas and issues in the other books became useful. I was very particular that The Kills would show an occupation from the occupiers perspective -- my father was in the military, and this was my experience of Malta, Cyprus, Germany, where we had very limited interaction with any local population. In the Naples story, I was able to look, in a small way, at the other side of an occupation, and by setting that in Europe, and referring to WWII, I could give a perspective to what an occupation could mean, one that most of us could readily follow. What was happening in Iraq was immediate, we could see it in the news as it happened. But it was also removed, in happening in some remote place about which we have no proper or developed understanding. Iraq is somewhere else, foreign, distant. It's almost a rule of action, that every country in which we have a conflict (I'm specifically thinking of the U.K. here) becomes abstract, and in some way, lesser. This is exactly what happened in Naples in 1943. If you look at a place as a theatre for war, then it makes it easier for us not to consider the reality of what is happening. That makes the consequences very hard, very bitter -- and long term. I think the third book, “The Kill,” was a way of looking at this from a different angle.

Almost every character is out of water, in some circumstance they can't control, to which they have to adapt, change, react. In “The Kill” the characters are outside in some way, being foreign, unable to speak a language, a sex worker, gay, not that these are equitable positions in any way, but they each add a level of complication to how they manage in the world. The same fish out of water issue stands for [several other characters].

“The Kill” works from a basic proposition. Two brothers deciding “what if.” There's no consideration of what might happen afterward. In fact, there's some delight for these brothers in how they leave behind them as big a mess as possible. I don't believe this was our intention in Iraq, but it is the effect. There's something deliberate and wilful about breaking a country apart and in attempting to restructure it as a marketplace -- particularly a country which largely worked on traditional models of kinship and association. We demolished a country, every structure was devalued, disassembled, and when we came to reassemble it, we just couldn't manage. Parts of Europe underwent similar destruction, except our obligation to restructure -- propelled by a fear of communism -- was followed through -- for good or bad.

JV: I've heard "The Kill" was written first. Did the rest accrete around that? How much exploration was there structurally for you?

RH: I wanted to write something like Leonardo Sciascia's Equal Danger, a short book that starts out as a crime novel but quickly unravels, and while seeming to be simple (the murder of high court judges) it addresses why these killings are happening, rather than who is doing the killing. Which is a smart distinction, and it opens up an ever-expanding problem. It's a scary read, and there's a film version by Francesco Rosi called Cadaveri Eccelente that was largely shot in Naples and is superb.

I took a side trip to Naples, thinking I'd write something lighter and quicker than usual, and ended up spending a considerable amount of time there, back and forth, over a couple of years. Whenever I met people, Italians, there would be this groaning realisation that if I was a writer, in Naples, then I'd probably be writing a crime novel or a thriller, and that the city was, and is, overburdened with these narratives. I set the book aside, and once the main story based on the Massive developed (the idea of a city being built in the desert in Iraq, and of focussing on contractors rather than the military) I included "The Kill," the novel set in Naples, as a private reference. Not a joke exactly, but I didn't want to let those ideas disappear.

JV: Did you realize after you'd finished The Kills that you might've written something that mimicked certain genres but didn't really fulfill the trope-arc of those genres?

RH: I wanted to play with different kinds of narratives, partly because, as a reader, it sets up an expectation. As a writer it is hugely interesting to twist and articulate, and also frustrate those expectations. I'm a big fan of Wilkie Collins The Moonstone because almost too much is happening, it's uncategorisable because it acknowledges different expectations -- it's a penny-thriller, a heist (sort of), a ghost story, a romance, a story divided between narrators and forms. Big fun. Thrillers and crime novels are also populated by different kinds of characters, which is for me their main pleasure. Mainstream literature can tend towards normalization -- even when characters aren't straight and white, they might as well be for all of the values represented. While thrillers and crime novels tend to freak difference and can be hugely problematic in how they stereotype (particularly women), they also show difference. I might not like some of the gay characters I read in crime novels, but once in a while there will be some humane, amazing character that I just won't find anywhere else. I think I'm mimicking that kind of inclusion. I hope that those smaller characters (particularly in “The Kill”) matter. Part of how I worked their stories is that you're engaged with a character only when and where they intersect the main narrative -- more or less.

This might not be right, but when I read a thriller the characters, in some ways, fit the narrative, they work within that world, so much so that you're right in that world with them, but they are clearly constructions. I'm aiming for that. There's a real pleasure for me in seeing the artifice of something while you are also involved within it. A performer, Nancy Forrest Brown, used to perform these events where she would inhabit these characters, which was a kind of a drag act in a way. You'd be aware that this character was Nancy, but also, simultaneously, this character. I love that fluctuation. Fiction does that for me. Fake and real at the same time. Genre writing excels in this.

In terms of structure, I think readers are, or can be, highly sophisticated. As soon as a story starts we're already working on the middle and the ending -- and while we progress through a book tiny modifications or clarifications are happening to that overall plan. I prefer works which mess with this, and articulate themselves in unanticipated ways. Not fulfilling a genre's expectation is going to frustrate a reader, and in some ways I take it for granted that a reader can complete a story arc without it needing to be spelled out. I have a particular dislike of being instructed, of being told how everything works, how I should feel, how I should think. Closure is an artifice, and it's also the point where a writer can display their moral position or a neatly packaged world view -- which is almost always problematic. I don't read to be instructed, I read to discover and debate and to be challenged.

JV: Did you think that you were writing something metafictional just because a text embedded in your narrative replicates itself in people's minds? I don't personally see the novel as metafictional, but that might just be my world view intruding.

RH: Good question. There are certain pleasures here, some quotes from other writers that I love -- in many senses the book is a map of writing that I value. There's Sciascia, Highsmith, a bunch of others I forget. What I enjoyed in writing The Kills is that I'd given myself something huge to work across, and that some ideas could be re-articulated, and that other ideas could be set and returned to many hundreds of pages later. It's tricky, because I'd like to set up a narrative where some associations or links are explicit, and others are implicit, without impeding the story. It would make me very happy if a reader started to make connections I hadn't intended. I wanted to set up that potential. When I think about events in my own past I often have realizations -- 'oh, ok, that meant such and such,' -- notions which you revisit, revise, there's the potential for this in a long-form narrative.

JV: There's the novel in your head and then the novel on the page, and then the novel in the reader's head. Have readers, generally, gotten what you were going for? The novel tends to keep making you re-evaluate how to read it from section to section.

RH: I have to be totally honest. Most discussions, frustratingly, are about the book's size. It takes a certain temperament and intention to take on. We're all watching that "% of pages read" progress bar on the kindle or iPad, which turns a novel into a challenge, not an experience, and takes out all of the pleasure. I've had a few people ask what happened to Eric, or Sutler, or Lila, and I love the idea that this question means that they could push the stories further for themselves.

I wanted a book that was packed with ideas and invention, without being too cumbersome. I also wanted a book which shifts in direction and has a logic that assembles itself as you read. I think I achieved that.

JV: What's been the most interesting reader or reviewer response?

RH: A great deal of writing is about process, and about finding your way, so reviews are useful in helping me reflect back on what I've done. I think I was a little stunned once it was finished, so any kind of discussion helps me gain perspective, and I'm very grateful for that. It's a scary prospect putting out something so huge and so involved. The book has received some passionate and particular support. As a very general rule, people who read a hell of a lot tend to get the overall project. People who don't tend to read a huge amount think, erm, well, what kind of a thriller is this? Which makes the book a tough proposal. It makes me unspeakably happy when someone does get it. Some reviewers have asked questions about genre, which has been hugely productive for me to consider.

A good number of people think I invented the burn pits. Which sadly exist, and have caused ongoing health problems, perhaps even some deaths.

JV: Did Sutler make it out?

RH: No. I think not. You know that frozen man, Otzi...

Tuesday New Release Day: Grossman; House; Gaffney; Montefiore; Tanweer; Leslie-Hynan; Brooks; Gordon; Livings; Schottenfeld; Kennedy; Bertino; Gay

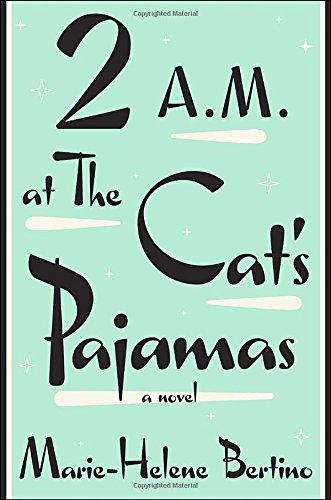

Out this week: The Magician's Land by Lev Grossman; The Kills by Richard House; When the World Was Young by Elizabeth Gaffney; Secrets of the Lighthouse by Santa Montefiore; The Scatter Here is Too Great by Bilal Tanweer; Ride Around Shining by Chris Leslie-Hynan; Painted Horses by Malcolm Brooks; The Liar’s Wife by Mary Gordon; The Dog by Jack Livings; Bluff City Pawn by Stephen Schottenfeld; Beneath the Neon Egg by Thomas E. Kennedy; 2 A.M. at The Cat’s Pajamas by Marie-Helene Bertino; and Bad Feminist by Year in Reading alum Roxane Gay, who also came out with a novel a few months ago.

Most Anticipated: The Great Second-Half 2014 Book Preview

2014 has already offered a literary bounty for readers, including new books by E.L. Doctorow, Lorrie Moore, Teju Cole, and Lydia Davis. The second-half of 2014 is looking even more plentiful, with new books from superstars like Haruki Murakami, David Mitchell, Ian McEwan, Marilynne Robinson, Denis Johnson, Hilary Mantel, Margaret Atwood and quite a few more. Here at The Millions, we're especially excited that three of our long-time staff writers -- Edan Lepucki, Bill Morris, and Emily St. John Mandel -- will soon have new books on shelves. All three books are winning impressive advance praise.

The list that follows isn’t exhaustive – no book preview could be – but, at over 8,000 words strong and encompassing 84 titles, this is the only second-half 2014 book preview you will ever need. Scroll down and get started.

July:

California by Edan Lepucki: Millions staffer Edan Lepucki’s first full-length novel has been praised by Jennifer Egan, Dan Chaon, and Sherman Alexie, and championed by Stephen Colbert, who’s using it as a case study in sticking it to Amazon. A post-apocalyptic novel set in a California of the not-too-distant future, California follows a young couple struggling to make it work in a shack in the wilderness — dealing with everyday struggles like marriage and privacy as much as dystopian ones likes food and water — until a change in circumstance sends them on a journey to find what’s left of civilization, and what’s left of their past lives. (Janet)

Motor City Burning by Bill Morris: Bill Morris made his literary debut 20 years ago with Motor City, a novel set amid the rich history of 1950s Detroit. Since then, he's pursued various other interests, writing a novel set in Bangkok and contributing frequently to The Millions as a staff writer. But as anyone who follows Bill's essays can tell you, his hometown is rarely far from his mind. Now, with the Motor City much in the news, he returns to explore class, race, bloodshed and baseball in the 1960s. (Garth)

The Land of Love and Drowning by Tiphanie Yanique: Tiphanie Yanique follows her much lauded story collection, How to Escape From a Leper Colony, with “an epic multigenerational tale set in the U.S. Virgin Islands that traces the ambivalent history of its inhabitants during the course of the 20th century.” That’s according to Publishers Weekly, who gave The Land of Love and Drowning a starred review. Yanique’s debut novel has been receiving raves all over the place; in its starred review, Kirkus called it, “Bubbling with talent and ambition, this novel is a head-spinning Caribbean cocktail.” (Edan)

Friendship by Emily Gould: Gould, who put the gawk in Gawker in the middle part of the last decade, turns to fiction with a debut novel that at times reads like a series of blog entries written in the third person. In the novel, two friends, Bev and Amy, are trying to make it as writers in New York when Bev gets pregnant. The question of whether Bev should keep the baby, and what Amy should think about the fact that Bev is even considering it, turns the novel into a meditation on growing up in a world built for the young. (Michael)

Last Stories and Other Stories by William T. Vollmann: Vollmann has over 30 years and damn near as many books earned a reputation as a wildly prolific novelist. Still, almost a decade has passed since his last full-length work of fiction, the National Book Award-winning Europe Central. Here, he offers what may have started as a suite of ghost stories… but is now another sprawling atlas of Vollmann's obsessions. Stories of violence, romance, and cultural collision are held together by supernatural elements and by Vollmann's psychedelically sui generis prose. (Garth)

High as the Horses' Bridles by Scott Cheshire: To the distinguished roster of fictional evangelicals — Faulkner's Whitfield, Ellison's Bliss — this first novel adds Josiah Laudermilk, a child-prodigy preacher in 1980s Queens. Cheshire makes huge leaps in time and space to bring us the story of Laudermilk's transformation into an adult estranged from his father and his faith. (Garth)

The Hundred-Year House by Rebecca Makkai: The second novel from Rebecca Makkai (after 2011’s The Borrower) moves back and forth in the 20th century to tell a story of love, ghosts, and intrigue. The house for which The Hundred-Year House is named is Laurelfield, a rambling estate and former artists’ colony in Chicago’s wealthy North Shore. Owned by the Devohr family for generations, it now finds Zee (née Devohr) and her husband returning to live in the carriage house while she teaches at a local college and he supposedly writes a poet’s biography. What he does instead is ghostwrite teen novels and uncover family secrets. (Janet)

Tigerman by Nick Harkaway: Having written about ninjas, spies in their eighties and mechanical bees in his last two novels, Nick Harkaway is in a tough spot if he wants to top himself this time around. All the indications are that he may have done it, though — Tigerman sees a powerful United Nations carry out a cockamie plan to wipe out a former British colony. The protagonist, a former British soldier, takes it upon himself to fight for his patch of the old empire. (Thom)

Panic in a Suitcase by Yelena Akhtiorskaya: Yelena Akhtiorskaya is one of New York's best young writers — funny and inventive and stylistically daring, yes, but also clear-eyed and honest. Born in Odessa and raised in Brighton Beach, she's been publishing essays and fiction in smart-set venues for a few years. Now she delivers her first novel, about two decades in the life of a Ukrainian family resettled in Russian-speaking Brooklyn. An excerpt is available at n+1. (Garth)

The Great Glass Sea by Josh Weil: "And then one day when the lake ice had broken and geese had come again, two brothers, twins, stole a little boat and rowed together out towards Nizhi." In an alternate Russia, twin brothers Yarik and Dima work together at Oranzheria, the novel’s titular “sea of glass” greenhouse, until their lives veer into conflict. Weil’s exquisite pen and ink illustrations “frame the titles of all 29 chapters and decorate the novel’s endpapers,” making the book, literally, a work of art. If The New Valley, Weil’s lyric first book of linked novellas, is any indication, this new book will be memorable. (Nick R.)

August:

Colorless Tsukuru Tazaki and His Years of Pilgrimage by Haruki Murakami: Murakami's previous novel, 1Q84, was a sprawling, fantastical work. His latest is just the opposite: a concise, focused story about a 37-year-old man still trying to come terms with a personal trauma that took place seventeen years earlier — when he was unceremoniously cut out of a tight knit group of friends. The novel has less magical strangeness than most Murakami books, and may be his most straightforward tale since Norwegian Wood. (Kevin)

We Are Not Ourselves by Matthew Thomas: Thomas spreads his canvas wide in this 640-page doorstop of a novel, which follows three generations of an Irish American family from Queens, but at heart the book is an intimate tale of a family’s struggle to make its peace with a catastrophic illness that strikes one of its members at precisely the wrong moment. Simon & Schuster spent more than a million dollars on this first novel whose author was then teaching high school in New York, thus assuring that the book will either be the fall’s Cinderella story or a poster child for outsized advances given to untested authors. (Michael)

Bad Feminist by Roxane Gay: Is it “the year of Roxane Gay?” Time suggested it in a review of Gay’s new novel, An Untamed State; when asked (in a self-interview) how that made her feel, she said, “First, I tinkled on myself. Then my ego exploded and I am still cleaning up the mess.” It’s as good a glimpse as any into the wonder that is Roxane Gay — her Twitterstorms alone are brilliant bits of cultural criticism, and her powerful essays, on her blog, Tumblr, and at various magazines, leave you with the sense that this is a woman who can write dazzlingly on just about any topic. In her first essay collection, we’re promised a wide-ranging list of subjects: Sweet Valley High, Django Unchained, abortion, Girls, Chris Brown, and the meaning of feminism. (Elizabeth)

The Kills by Richard House: House's vast tetralogy, at once a border-hopping thriller and a doorstopping experiment, was longlisted for last year's Man Booker Prize in the U.K. Taking as its backdrop the machinery of the global war on terror, it should be of equal interest on these shores. (Garth)

Before, During, After by Richard Bausch: Since 1980, Richard Bausch has been pouring out novels and story collections that have brilliantly twinned the personal with the epic. His twelfth novel, Before, During, After, spins a love story between two ordinary people – Natasha, a lonely congressional aide, and Michael Faulk, an Episcopalian priest – whose affair and marriage are undone by epic events, one global, one personal. While Michael nearly dies during the 9/11 terrorist attacks, Natasha’s error on a Caribbean shore leads to a private, unspeakable trauma. As the novel unspools, Before and During prove to be no match for After. (Bill)

Your Face In Mine by Jess Row: Possibly inspired by the ageless Black Like Me, Jess Row tells the story of Kelly Thorndike, a native Baltimorean who moves back to his hometown and discovers that an old friend has gotten surgery to change his race. At one time a skinny, white, Jewish man, Martin is now African-American, and he's kept his new identity secret from his friends and family. Martin tells Kelly he wants to come clean, and the two become mired in a fractious, thought-provoking controversy. (Thom)

Flings by Justin Taylor: "Our faith makes us crazy in the world"; so reads a line in The Gospel of Anarchy, Taylor’s novel about a Florida commune of anarchist hippies. The original sentence comes from Don DeLillo’s Mao II, an appropriate literary mentor — Taylor is equal parts hilarious and prescient, capable of finding the sublime in the most prosaic, diverse material. On the first page of the collection’s title story alone: labor history, love, and "an inspired treatise on the American government's illegal 1921 deployment of the Air Force to bomb striking mine workers at Blair Mountain, West Virginia." (Nick R.)

Augustus by John Williams: There are things that are famous for being famous, such as the Kardashians, and then there are things that are famous for being not famous, such as John Williams’s Stoner. Since its publication in 1965, the “forgotten” work has enjoyed quite a history – metamorphosing from under-appreciated gem into international bestseller and over-praised classic. Indeed, it’s forgivable at this point to forget that Williams’s most appreciated work was actually his final novel, Augustus, which split the National Book Award and earned more praise during its author's lifetime than his other books put together. Interestingly, readers of both Stoner and Butcher's Crossing will here encounter an altogether new version of the John Williams they've come to know: Augustus is an epistolary novel set in classical Rome. It's a rare genius who can reinvent himself in his final work and earn high praise for doing so. (Nick M.)

Alfred Ollivant's Bob, Son of Battle by Lydia Davis: In the early 1900s, Bob, Son of Battle became a popular children's tale in England and the United States. Focused on a young boy caught up in a rivalry between two sheepdogs on the moors between Scotland and England, the story eventually found its way into Lydia Davis's childhood bedroom. Alas, the years have not been kind to the thick Cumbrian dialect in which it was written ("hoodoo" = "how do you do" and "gammy" = "illness," e.g.) and the work fell out of popularity as a result. Now, however, Davis has updated the work into clear, modern vernacular in order to bring the story to an entirely new generation of readers, and perhaps the next generation of Lydia Davises (if one could ever possibly exist). (Nick M.)

September:

Station Eleven by Emily St. John Mandel: Station Eleven is Millions staff writer Emily St. John Mandel's fourth novel, and if pre-publication buzz is any indication, it's her best, most ambitious work yet. Post-apocalyptic tales are all the rage this season, but Mandel's intricate plotting and deftness with drawing character makes this novel of interlinked tales stand out as a beguiling read. Beginning with the onslaught of the deadly Georgian flu and the death of a famous actor onstage, and advancing twenty years into the future to a traveling troupe of Shakespearean actors who perform for the few remaining survivors, the novel sits with darkness while searching for the beauty in art and human connection. (Anne)

The Secret Place by Tana French: People have been bragging about snagging this galley all summer, and for good reason: Tana French’s beautifully written, character-driven mysteries about the detectives of the Dublin Murder Squad are always a literary event. Her latest concerns a murder at an all girls’ school, and detective Frank Mackey’s daughter Holly might just be a suspect. My fellow staff writer Janet Potter said The Secret Place is damn good, and if you're smart you will trust Janet Potter. (Edan)

The Bone Clocks by David Mitchell: David Mitchell has evidently returned to his genre-, time-, and location-bending best with a novel that weaves the Iraq War with punk rock with immortal beings with the End Times. This is a novel that had Publisher’s Weekly asking, “Is The Bone Clocks the most ambitious novel ever written, or just the most Mitchell-esque?” A tall order, either way. A thrill, either way. (Lydia)

Not That Kind of Girl by Lena Dunham: The creator, producer and star of the HBO series Girls — and also, it must be stated, an Oberlin College graduate — has penned a comic essay collection à la David Sedaris or Tina Fey… though something tells me Dunham’s will be more candid and ribald. As Lena herself writes: “No, I am not a sexpert, a psychologist, or a registered dietician. I am not a married mother of three or the owner of a successful hosiery franchise. But I am a girl with a keen interest in self-actualization, sending hopeful dispatches from the front lines of that struggle.” Amen, Lena, amen! (Edan)

The Paying Guests by Sarah Waters: After her masterful handling of the haunted house story in The Little Stranger, Waters again taps into the narrative potential of domestic intrusion. This time, it’s lodgers rather than ghosts who are the nuisance. In 1922, a cash-strapped widow and her spinster daughter living by themselves in a large London house let out rooms to a young couple. Annoyances and class tensions soon ignite in these combustible confines, and from the looks of it, the security deposit won’t even begin to cover the damages. The novel promises to be a well-crafted, claustrophobic thriller. (Matt)

The Children Act by Ian McEwan: McEwan’s thirteenth novel treads some familiar ground — a tense moral question sits at the heart of the narrative: whether it is right for parents to refuse medical treatment for their children on religious grounds. Discussing the novel at the Oxford Literary Festival this past spring, McEwan said that the practice was “utterly perverse and inhumane.” It’s not the first time McEwan has expressed displeasure with religion: in 2005 he told the Believer he had “no patience whatsoever” for it; three years later, he made international news discussing Islam and Christianity, saying he didn’t “like these medieval visions of the world according to which God is coming to save the faithful and to damn the others.” (Elizabeth)

10:04 by Ben Lerner: Ben Lerner follows the unexpected success of his superb first novel Leaving the Atocha Station with a book about a writer whose first novel is an unexpected success. Which is actually something like what you’d expect if you’d read that superb and unexpectedly successful first novel, with its artful manipulations of the boundaries between fiction and memoir. The suddenly successful narrator of 10:04 also gets diagnosed with a serious heart condition and is asked by a friend to help her conceive a child. Two extracts from the novel, “Specimen Days” and “False Spring,” have run in recent issues of the Paris Review. (Mark)

Stone Mattress: Nine Tales by Margaret Atwood: Some fans will remember well the titular story in Atwood’s forthcoming collection, which was published in the New Yorker in December of 2011, and which begins, in Atwood's typical-wonderful droll fashion: “At the outset, Verna had not intended to kill anyone.” With this collection, according to the jacket copy, “Margaret Atwood ventures into the shadowland earlier explored by fabulists and concoctors of dark yarns such as Robert Louis Stevenson, Daphne du Maurier and Arthur Conan Doyle…” If you aren’t planning to read this book, it means you like boring stuff. (Edan)

The Assassination of Margaret Thatcher: Stories by Hilary Mantel: Just this month, Mantel was made a dame; the reigning queen of British fiction, she’s won two of the last five Man Booker Prizes. But Mantel’s ascension to superstardom was long in the making: she is at work on her twelfth novel in a career that’s spanned four decades. This fall sees the publication of her second collection of short stories, set several centuries on from the novels that earned her those Bookers. Her British publisher, Nicholas Pearson, said, “Where her last two novels explore how modern England was forged, The Assassination of Margaret Thatcher shows us the country we have become. These stories are Mantel at her observant best.” (Elizabeth)

The Dog by Joseph O'Neill: In his first novel since his 2008 PEN/Faulkner-winning Netherland, about a Dutch immigrant in post 9/11 New York, O’Neill tells another fish-out-of-water tale, this time about a New Yorker who takes a job as a “family officer” for a wealthy family in Dubai. Surrounded by corruption and overwhelmed by daily life in the desert metropolis, the narrator becomes obsessed with the disappearance of another American in what Publishers Weekly calls “a beautifully crafted narrative about a man undone by a soulless society.” (Michael)

Barbarian Days by William Finnegan: William Finnegan is both a journalist's journalist and one of the New Yorker's most consistently engaging voices. Over the years, he's written about everything from apartheid in South Africa to the broken economy at home (Cold New World now looks prophetic). My favorite of his New Yorker pieces, though, is an insanely long memoir about surfing (Part 1; Part 2) that, legend has it, was crashed into the magazine just before the arrival of Tina Brown as editor. Two decades on, Finnegan returns to this lifelong passion, at book length.

Wittgenstein, Jr. by Lars Iyer: With their ingenious blend of philosophical dialogue and vaudevillian verve, Iyer's trilogy, Spurious, Dogma and Exodus, earned a cult following. Wittgenstein, Jr. compacts Iyer's concerns into a single campus novel, set at early 21st-century Cambridge. It should serve as an ideal introduction to his work. (Garth)

The Emerald Light in the Air by Donald Antrim: No one makes chaos as appealing a spectacle as Antrim, whether it’s unloosed on the dilapidated red library from The Hundred Brothers, its priceless rugs, heraldic arms and rare books threatened by drunken siblings and a bounding Doberman; the pancake house from The Verificationist; or the moated suburban neighborhood from Elect Mr. Robinson for a Better World. His latest is a collection of stories written over the past fifteen years, each of which was published in the New Yorker. The Emerald Light in the Air demonstrates that Antrim’s controlled anarchy translates beautifully to the shorter form. (Matt)

Hold the Dark by William Giraldi: Having built a reputation for critical savagery following the hatchet he sank into a pair of Alix Ohlin books in the Times in 2012, Giraldi puts his own neck on the line with this literary thriller set in a remote Alaskan village where wolves are eating children. Billed as an “Alaskan Oresteia,” the novel follows a pair of men, one an aging nature writer, the other a returning soldier, who come to learn secrets “about the unkillable bonds of family, and the untamed animal in the soul of every human being.” That sound you hear is the whine of blades touching grindstones across literary America. (Michael)

Barracuda by Christos Tsiolkas: The title of Christos Tsiolkas’s fifth novel — his first since the international bestseller, The Slap — is a nickname for Daniel Kelly, an Australian swimming prodigy so ruthless in the water that he gets likened to the sharp-toothed, predatory fish. But Daniel’s Olympic ambitions are thwarted by a crime whose nature Tsiolkas hints at but shrewdly withholds. This novel, like all of Tsiolkas’s work, is a vigorous, sometimes vicious argument about what it means to be Australian. As one character concludes, “We are parochial and narrow-minded and we are racist and ungenerous and…” It gets worse, gorgeously worse. (Bill)

Prelude to Bruise by Saeed Jones: You’re showing your age and (lack of) internet bona fides if you admit that you’re unfamiliar with Jones’s work. For years now the Buzzfeed LGBT editor has been lighting it up at his day job, and also on Twitter, with a ferocity befitting his name. Now, after earning praise from D.A. Powell and after winning a NYC-based Literary Death Match bout, Jones will use his debut collection to prominently display his poetry chops. (Ed. note: check out an excerpt over here.) (Nick M.)

Faithful and Virtuous Night by Louise Glück: The UK publisher (Carcanet) of Louise Glück’s newest collection — her twelfth — describes the poems as “a sequence of journeys and explorations through time and memory.” Macmillan describes it as “a story of adventure, an encounter with the unknown, a knight’s undaunted journey into the kingdom of death; this is a story of the world you’ve always known... every familiar facet has been made to shimmer like the contours of a dream…” In other words, Glück’s newest work is interested in a kind of reiterative, collage-like experience of narrative — “tells a single story but the parts are mutable.” (Sonya)

Gangsterland by Tod Goldberg: In Goldberg’s latest novel, infamous Chicago mafia hit man Sal Cupertine must flee to Las Vegas to escape the FBI, where he assumes the identity of… Rabbi David Cohen. The Mafia plus the Torah makes for a darkly funny and suspenseful morality tale. Goldberg, who runs UC Riverside-Palm Desert’s low residency MFA program, is also the author of Living Dead Girl, which was an LA Times Fiction Prize finalist, and the popular Burn Notice series, among others. The man can spin a good yarn. (Edan)

Happiness: Ten Years of n+1 by Editors of n+1: Happiness is a collection of the best pieces from n+1’s first decade, selected by the magazine’s editors. Ten years is a pretty long time for any literary journal to continue existing, but when you consider the number of prominent younger American writers who have had a long association with the magazine, it’s actually sort of surprising that it hasn’t been around longer. Chad Harbach, Keith Gessen, Benjamin Kunkel and Elif Batuman all launched their careers through its pages. Pieces by these writers, and several more, are included here. (Mark)

Neverhome by Laird Hunt: According to letters and accounts from the time, around 400 women disguised themselves as men to fight in the Civil War. Years ago, Laird Hunt read a collection of one of those women’s letters, and the idea for this novel has been germinating ever since. It tells the story of Constance Thompson, a farm wife who leaves her husband behind, calls herself Ash and fights for the Union. Neverhome is both a story about the harrowing life of a cross-dressing soldier, and an investigation into the mysterious circumstances that led her there. (Janet)

My Life as a Foreign Country by Brian Turner: Brian Turner served for seven years in the US Army, spending time in both Bosnia-Herzegovina and Iraq. Since then, he has published two collections of poetry — Here, Bullet and the T.S. Elliot Prize-shortlisted Phantom Noise — both of which draw heavily on his experiences in those wars. His new book is a memoir about his year in Iraq, and about the aftermath of that experience. Turner also makes a leap of conceptual identification, attempting to imagine the conflict through the experience of the Iraqi other. Tim O’Brien, author of The Things They Carried, has praised it as “brilliant and beautiful”, and as ranking “with the best war memoirs I’ve ever encountered”. (Mark)

Wallflowers: Stories by Eliza Robertson: Robertson's stories — often told from the perspectives of outsiders, often concerned with the mysteries of love and family, set in places ranging from the Canadian suburbs to Marseilles — have earned her a considerable following in her native Canada. Her debut collection includes "We Walked on Water," winner of the Commonwealth Short Story Prize, and "L'Etranger," shortlisted for the CBC Short Story Prize. (Emily)

On Bittersweet Place by Ronna Wineberg: On Bittersweet Place is the second publication from Relegation Books, a small press founded by author Dallas Hudgens. The novel — Wineberg's first, following her acclaimed story collection Second Language — concerns Lena Czernitski, a young Russian Jewish immigrant trying to find her place in the glamour and darkness of 1920s Chicago. (Emily)

The Betrayers by David Bezmozgis: Following on the heels of the acclaimed The Free World, Bezmozgis's second novel is about 24 hours in the life of Baruch Kotler, a disgraced Israeli politician who meets the Soviet-era spy who denounced him decades earlier. (Kevin)

How to Build a Girl by Caitlin Moran: The feminist journalist and author of How to Be a Woman, once called “the UK’s answer to Tina Fey, Chelsea Handler, and Lena Dunham all rolled into one” by Marie Claire, is publishing her first novel. It follows Johanna Morrigan, who at 14 decides to start life over as Dolly Wilde. Two years later she’s a goth chick and “Lady Sex Adventurer” with a gig writing reviews for a music paper, when she starts to wonder about what she lost when she reinvented herself. (Janet)

On Immunity: An Innoculation by Eula Biss: When Biss became a mother, she began looking into the topic of vaccination. What she had assumed would be a few hours of personal research turned into a fascination, and the result is a sweeping work that considers the concept of immunity, the history of vaccination — a practice that sometimes seems to function as a lightning rod for our most paranoid fears about the chemical-laden modern world in which we find ourselves, but that has its roots in centuries-old folk medicine — and the ways in which we're interconnected, with meditations on writers ranging from Voltaire to Bram Stoker. (Emily)

October:

Yes, Please by Amy Poehler: The Leslie Knopes among us cannot wait for Poehler’s first book of personal stories and advice, in the vein of Tina Fey’s Bossypants and Mindy Kaling’s Is Everyone Hanging Out Without Me? In Poehler’s delightful New Yorker essay about her job at an ice cream parlor, she wrote, “It’s important to know when it’s time to turn in your kazoo.” Wise words from one of America's most beloved comics and actresses. (Anne)

The Peripheral by William Gibson: William Gibson fans rejoice, for his first novel in four years is upon us. The novel follows an army veteran with futuristic nerve damage wrought during his time in a futuristic kill squad. (Technically, according to Gibson, it’s a novel taking place in multiple futures, so it’s probably more complicated than that). You can watch him read the first two pages here. If William Gibson were a tense, he’d be future-noir. (Lydia)

Lila by Marilynne Robinson: Marilynne Robinson published her brilliant debut novel Housekeeping in 1980 and then basically went dark for a decade and a half, but has been relatively prolific in the last ten years. After re-emerging with 2004’s gorgeous and heartbreaking Gilead, she followed up four years later with Home, a retelling of the prodigal son parable that revisited a story and characters from Gilead. James Wood’s description of the relationship between the two books is exact and lovely: “Home is not a sequel [to Gilead],” he wrote, “but more like that novel’s brother.” With her new novel, Robinson has given those books a sister. The novel tells the story of Lila – the young bride of Gilead’s narrator, Rev. John Ames – who was abandoned as a toddler and raised by a drifter. (Mark) (Ed. Note: You can read an excerpt over here.)