Mentioned in:

A Year in Reading: 2024

Welcome to the 20th (!) installment of The Millions' annual Year in Reading series, which gathers together some of today's most exciting writers and thinkers to share the books that shaped their year. YIR is not a collection of yearend best-of lists; think of it, perhaps, as an assemblage of annotated bibliographies. We've invited contributors to reflect on the books they read this year—an intentionally vague prompt—and encouraged them to approach the assignment however they choose.

In writing about our reading lives, as YIR contributors are asked to do, we inevitably write about our personal lives, our inner lives. This year, a number of contributors read their way through profound grief and serious illness, through new parenthood and cross-country moves. Some found escape in frothy romances, mooring in works of theology, comfort in ancient epic poetry. More than one turned to the wisdom of Ursula K. Le Guin. Many describe a book finding them just when they needed it.

Interpretations of the assignment were wonderfully varied. One contributor, a music critic, considered the musical analogs to the books she read, while another mapped her reads from this year onto constellations. Most people's reading was guided purely by pleasure, or else a desire to better understand events unfolding in their lives or larger the world. Yet others centered their reading around a certain sense of duty: this year one contributor committed to finishing the six Philip Roth novels he had yet to read, an undertaking that he likens to “eating a six-pack of paper towels.” (Lucky for us, he included in his essay his final ranking of Roth's oeuvre.)

The books that populate these essays range widely, though the most commonly noted title this year was Tony Tulathimutte’s story collection Rejection. The work of newly minted National Book Award winner Percival Everett, particularly his acclaimed novel James, was also widely read and written about. And as the genocide of Palestinians in Gaza enters its second year, many contributors sought out Isabella Hammad’s searing, clear-eyed essay Recognizing the Stranger.

Like so many endeavors in our chronically under-resourced literary community, Year in Reading is a labor of love. The Millions is a one-person editorial operation (with an invaluable assist from SEO maven Dani Fishman), and producing YIR—and witnessing the joy it brings contributors and readers alike—has been the highlight of my tenure as editor. I’m profoundly grateful for the generosity of this year’s contributors, whose names and entries will be revealed below over the next three weeks, concluding on Wednesday, December 18. Be sure to subscribe to The Millions’ free newsletter to get the week’s entries sent straight to your inbox each Friday.

—Sophia Stewart, editor

Becca Rothfeld, author of All Things Are Too Small

Carvell Wallace, author of Another Word for Love

Charlotte Shane, author of An Honest Woman

Brianna Di Monda, writer and editor

Nell Irvin Painter, author of I Just Keep Talking

Carrie Courogen, author of Miss May Does Not Exist

Ayşegül Savaş, author of The Anthropologists

Zachary Issenberg, writer

Tony Tulathimutte, author of Rejection

Ann Powers, author of Traveling: On the Path of Joni Mitchell

Lidia Yuknavitch, author of Reading the Waves

Nicholas Russell, writer and critic

Daniel Saldaña París, author of Planes Flying Over a Monster

Lili Anolik, author of Didion and Babitz

Deborah Ghim, editor

Emily Witt, author of Health and Safety

Nathan Thrall, author of A Day in the Life of Abed Salama

Lena Moses-Schmitt, author of True Mistakes

Jeremy Gordon, author of See Friendship

John Lee Clark, author of Touch the Future

Ellen Wayland-Smith, author of The Science of Last Things

Edwin Frank, publisher and author of Stranger Than Fiction

Sophia Stewart, editor of The Millions

A Year in Reading Archives: 2023, 2022, 2021, 2020, 2019, 2018, 2017, 2016, 2015, 2014, 2013, 2011, 2010, 2009, 2008, 2007, 2006, 2005

The Great Fall 2024 Book Preview

With the arrival of autumn comes a deluge of great books. Here you'll find a sampling of new and forthcoming titles that caught our eye here at The Millions, and that we think might catch yours, too. Some we’ve already perused in galley form; others we’re eager to devour based on their authors, plots, or subject matters. We hope your next fall read is among them.

—Sophia Stewart, editor

October

Season of the Swamp by Yuri Herrera, tr. Lisa Dillman [F]

What it is: An epic, speculative account of the 18 months that Benito Juárez spent in New Orleans in 1853-54, years before he became the first and only Indigenous president of Mexico.

Who it's for: Fans of speculative history; readers who appreciate the magic that swirls around any novel set in New Orleans. —Claire Kirch

The Black Utopians by Aaron Robertson [NF]

What it is: An exploration of Black Americans' pursuit and visions of utopia—both ideological and physical—that spans the Reconstruction era to the present day and combines history, memoir, and reportage.

Who it's for: Fans of Saidiya Hartman's Wayward Lives, Beautiful Experiments and Kristen R. Ghodsee's Everyday Utopia. —Sophia M. Stewart

The Third Realm by Karl Ove Knausgaard, tr. Martin Aitken [F]

What it is: The third installment in Knausgaard's Morning Star series, centered on the appearance of a mysterious new star in the skies above Norway.

Who it's for: Real Knausgaard heads only—The Wolves of Eternity and Morning Star are required reading for this one. —SMS

Brown Women Have Everything by Sayantani Dasgupta [NF]

What it is: Essays on the contradictions and complexities of life as an Indian woman in America, probing everything from hair to family to the joys of travel.

Who it's for: Readers of Durga Chew-Bose, Erika L. Sánchez, and Tajja Isen. —SMS

The Plot Against Native America by Bill Vaughn [F]

What it is: The first narrative history of Native American boarding schools— which aimed "civilize" Indigenous children by violently severing them from their culture— and their enduring, horrifying legacy.

Who it's for: Readers of Ned Blackhawk and Kathleen DuVal. —SMS

The Mighty Red by Louise Erdrich [F]

What it is: Erdrich's latest novel set in North Dakota's Red River Valley is a tale of the intertwined lives of ordinary people striving to survive and even thrive in their rural community, despite environmental upheavals, the 2008 financial crisis, and other obstacles.

Who it's for: Readers of cli-fi; fans of Linda LeGarde Grover and William Faulkner. —CK

The Position of Spoons by Deborah Levy [NF]

What it is: The second book from Levy in as many years, diverging from a recent streak of surrealist fiction with a collection of essays marked by exceptional observance and style.

Who it's for: Close lookers and the perennially curious. —John H. Maher

The Bog Wife by Kay Chronister [F]

What it's about: The Haddesley family has lived on the same West Virginia bog for centuries, making a supernatural bargain with the land—a generational blood sacrifice—in order to do so—until an uncovered secret changes everything.

Who it's for: Readers of Karen Russell and Jeff VanderMeer; anyone who has ever used the phrase "girl moss." —SMS

The Great When by Alan Moore [F]

What it's about: When an 18-year old book reseller comes across a copy of a book that shouldn’t exist, it threatens to upend not just an already post-war-torn London, but reality as we know it.

Who it's for: Anyone looking for a Sherlock Holmes-style mystery dipped in thaumaturgical psychedelia. —Daniella Fishman

The Message by Ta-Nehisi Coates [NF]

What it's about: One of our sharpest critical thinkers on social justice returns to nonfiction, nearly a decade after Between the World and Me, visiting Dakar, to contemplate enslavement and the Middle Passage; Columbia, S.C., as a backdrop for his thoughts on Jim Crow and book bans; and the Israeli-occupied West Bank, where he sees contemporary segregation in the treatment of Palestinians.

Who it’s for: Fans of James Baldwin, George Orwell, and Angela Y. Davis; readers of Nikole Hannah-Jones’s The 1619 Project and Isabel Wilkerson’s Caste, to name just a few engagements with national and racial identity. —Nathalie op de Beeck

Abortion by Jessica Valenti [NF]

What it is: Columnist and memoirist Valenti, who tracks pro-choice advocacy and attacks on the right to choose in her Substack, channels feminist rage into a guide for freedom of choice advocacy.

Who it’s for: Readers of Robin Marty’s The New Handbook for a Post-Roe America, #ShoutYourAbortion proponents, and followers of Jennifer Baumgartner’s [I Had an Abortion] project. —NodB

Gifted by Suzuki Suzumi, tr. Allison Markin Powell [F]

What it's about: A young sex worker in Tokyo's red-light district muses on her life and recounts her abusive mother's final days, in what is Suzuki's first novel to be translated into English.

Who it's for: Readers of Susan Boyt and Mieko Kanai; fans of moody, introspective fiction; anyone with a fraught relationship to their mother. —SMS

Childish Literature by Alejandro Zambra, tr. Megan McDowell [F]

What it is: A wide-ranging collection of stories, essays, and poems that explore childhood, fatherhood, and family.

Who it's for: Fans of dad lit (see: Lucas Mann's Attachments, Keith Gessen's Raising Raffi, Karl Ove Knausgaard's seasons quartet, et al). —SMS

Books Are Made Out of Books ed. Michael Lynn Crews [NF]

What it is: A mining of the archives of the late Cormac McCarthy with a focus on the famously tight-lipped author's literary influences.

Who it's for: Anyone whose commonplace book contains the words "arquebus," "cordillera," or "vinegaroon." —JHM

Slaveroad by John Edgar Wideman [F]

What it is: A blend of memoir, fiction, and history that charts the "slaveroad" that runs through American history, spanning the Atlantic slave trade to the criminal justice system, from the celebrated author of Brothers and Keepers.

Who it's for: Fans of Clint Smith and Ta-Nehisi Coates. —SMS

Linguaphile by Julie Sedivy [NF]

What it's about: Linguist Sedivy reflects on a life spent loving language—its beauty, its mystery, and the essential role it plays in human existence.

Who it's for: Amateur (or professional) linguists; fans of the podcast A Way with Words (me). —SMS

An Image of My Name Enters America by Lucy Ives [NF]

What it is: A collection of interrelated essays that connect moments from Ives's life to larger questions of history, identity, and national fantasy,

Who it's for: Fans of Ives, one of our weirdest and most wondrous living writers—duh; anyone with a passing interest in My Little Pony, Cold War–era musicals, or The Three Body Problem, all of which are mined here for great effect. —SMS

Women's Hotel by Daniel Lavery [F]

What it is: A novel set in 1960s New York City, about the adventures of the residents of a hotel providing housing for young women that is very much evocative of the real-life legendary Barbizon Hotel.

Who it's for: Readers of Mary McCarthy's The Group and Rona Jaffe's The Best of Everything. —CK

The World in Books by Kenneth C. Davis [NF]

What it is: A guide to 52 of the most influential works of nonfiction ever published, spanning works from Plato to Ida B. Wells, bell hooks to Barbara Ehrenreich, and Sun Tzu to Joan Didion.

Who it's for: Lovers of nonfiction looking to cover their canonical bases. —SMS

Blue Light Hours by Bruna Dantas Lobato [F]

What it's about: Through the emanating blue-glow of their computer screens, a mother and daughter, four-thousand miles apart, find solace and loneliness in their nightly Skype chats in this heartstring-pulling debut.

Who it's for: Someone who needs to be reminded to CALL YOUR MOTHER! —DF

Riding Like the Wind by Iris Jamahl Dunkle [NF]

What it is: The biography of Sanora Babb, a contemporary of John Steinbeck's whose field notes and interviews with Dust Bowl migrants Steinbeck relied upon to write The Grapes of Wrath.

Who it's for: Steinbeck fans and haters alike; readers of Kristin Hannah's The Four Winds and the New York Times Overlooked column; anyone interested in learning more about the Dust Bowl migrants who fled to California hoping for a better life. —CK

Innie Shadows by Olivia M. Coetzee [F]

What it is: a work of crime fiction set on the outskirts of Cape Town, where a community marred by violence seeks justice and connection; also the first novel to be translated from Kaaps, a dialect of Afrikaans that was until recently only a spoken language.

Who it's for: fans of sprawling, socioeconomically-attuned crime dramas a la The Wire. —SMS

Dorothy Parker in Hollywood by Gail Crowther [NF]

What it is: A history of the famous wit—and famous New Yorker—in her L.A. era, post–Algonquin Round Table and mid–Red Scare.

Who it's for: Owners of a stack of hopelessly dog-eared Joan Didion paperbacks. —JHM

The Myth of American Idealism by Noam Chomsky and Nathan J. Robinson [NF]

What it is: A potent critique of the ideology behind America's foreign interventions and its status as a global power, and an treatise on how the nation's hubristic pursuit of "spreading democracy" threatens not only the delicate balance of global peace, but the already-declining health of our planet.

Who it's for: Chomskyites; policy wonks and casual critics of American recklessness alike. —DF

Mysticism by Simon Critchley [NF]

What it is: A study of mysticism—defined as an experience, rather than religious practice—by the great British philosopher Critchley, who mines music, poetry, and literature along the way.

Who it's for: Readers of John Gray, Jorge Luis Borges, and Simone Weil. —SMS

Q&A by Adrian Tomine [NF]

What it is: The Japanese American creator of the Optic Nerve comic book series for D&Q, and of many a New Yorker cover, shares his personal history and his creative process in this illustrated unburdening.

Who it’s for: Readers of Tomine’s melancholic, sometimes cringey, and occasionally brutal collections of comics short stories including Summer Blonde, Shortcomings, and Killing and Dying. —NodB

Sonny Boy by Al Pacino [NF]

What it is: Al Pacino's memoir—end of description.

Who it's for: Cinephiles; anyone curious how he's gonna spin fumbling Diane Keaton. —SMS

Seeing Baya by Alice Kaplan [NF]

What it is: The first biography of the enigmatic and largely-forgotten Algerian artist Baya Mahieddine, who first enchanted midcentury Paris as a teenager.

Who it's for: Admirers of Leonora Carrington, Hilma af Klint, Frida Kahlo, and other belatedly-celebrated women painters. —SMS

Absolution by Jeff VanderMeer [F]

What it is: A surprise return to the Area X, the stretch of unforbidding and uncanny coastline in the hit Southern Reach trilogy.

Who it's for: Anyone who's heard this song and got the reference without Googling it. —JHM

The Four Horsemen by Nick Curtola [NF]

What it is: The much-anticipated cookbook from the team behind Brooklyn's hottest restaurant (which also happens to be co-owned by James Murphy of LCD Soundsystem).

Who it's for: Oenophiles; thirty-somethings who live in north Williamsburg (derogatory). —SMS

Seeing Further by Esther Kinsky, tr. Caroline Schmidt [F]

What it's about: An unnamed German woman embarks on the colossal task of reviving a cinema in a small Hungarian village.

Who it's for: Fans of Jenny Erpenbeck; anyone charmed by Cinema Paradiso (not derogatory!). —SMS

Ripcord by Nate Lippens [NF]

What it's about: A novel of class, sex, friendship, and queer intimacy, written in delicious prose and narrated by a gay man adrift in Milwaukee.

Who it's for: Fans of Brontez Purnell, Garth Greenwell, Alexander Chee, and Wayne Koestenbaum. —SMS

The Use of Photography by Annie Ernaux and Marc Marie, tr. Alison L. Strayer [NF]

What it's about: Ernaux's love affair with Marie, a journalist, while she was undergoing treatment for cancer, and their joint project to document their romance.

Who it's for: The Ernaux hive, obviously; readers of Sontag's On Photography and Janet Malcolm's Still Pictures. —SMS

Nora Ephron at the Movies by Ilana Kaplan [NF]

What it is: Kaplan revisits Nora Ephron's cinematic watersheds—Silkwood, Heartburn, When Harry Met Sally, You've Got Mail, and Sleepless in Seattle—in this illustrated book. Have these iconic stories, and Ephron’s humor, weathered more than 40 years?

Who it’s for: Film history buffs who don’t mind a heteronormative HEA; listeners of the Hot and Bothered podcast; your coastal grandma. —NodB

[millions_email]

The Philosophy of Translation by Damion Searls [NF]

What it is: A meditation on the act and art of translation by one of today's most acclaimed practitioners, best known for his translations of Fosse, Proust, et al.

Who it's for: Regular readers of Words Without Borders and Asymptote; professional and amateur literary translators alike. —SMS

Salvage by Dionne Brand

What it is: A penetrating reevaluation of the British literary canon and the tropes once shaped Brand's reading life and sense of self—and Brand’s first major work of nonfiction since her landmark A Map to the Door of No Return.

Who it's for: Readers of Christina Sharpe's Ordinary Notes and Elizabeth Hardwick's Seduction and Betrayal. —SMS

Masquerade by Mike Fu [F]

What it's about: Housesitting for an artist friend in present-day New York, Meadow Liu stumbles on a novel whose author shares his name—the first of many strange, haunting happenings that lead up to the mysterious disappearance of Meadow's friend.

Who it's for: fans of Ed Park and Alexander Chee. —SMS

November

The Beggar Student by Osamu Dazai, tr. Sam Bett [F]

What it is: A novella in the moody vein of Dazai’s acclaimed No Longer Human, following the 30-something “fictional” Dazai into another misadventure spawned from a hubristic spat with a high schooler.

Who it's for: Longtime readers of Dazai, or new fans who discovered the midcentury Japanese novelist via TikTok and the Bungo Stray Dogs anime. —DF

In Thrall by Jane DeLynn [F]

What it is: A landmark lesbian bildungsroman about 16-year-old Lynn's love affair with her English teacher, originally published in 1982.

Who it's for: Fans of Joanna Russ's On Strike Against God and Edmund White's A Boy's Own Story —SMS

Washita Love Child by Douglas Kent Miller [NF]

What it is: The story of Jesse Ed Davis, the Indigenous musician who became on of the most sought after guitarists of the late '60s and '70s, playing alongside B.B. King, Bob Dylan, John Lennon, and more.

Who it's for: readers of music history and/or Indigenous history; fans of Joy Harjo, who wrote the foreword. —SMS

Set My Heart on Fire by Izumi Suzuki, tr. Helen O'Horan [F]

What it is: Gritty, sexy, and wholly rock ’n’ roll, Suzuki’s first novel translated into English (following her story collection, Hit Parade of Tears) follows 20-year-old Izumi navigating life, love, and music in the underground scene in '70s Japan.

Who it's for: Fans of Meiko Kawakami, Ursula K. Le Guin, and Marlowe Granados's Happy Hour. —DF

Didion & Babitz by Lili Anolik [NF]

What it is: A dual portrait of Joan Didion and Eve Babitz, who are so often compared to—and pitted against—each other on the basis of their mutual Los Angeles milieu.

Who it's for: Fans or haters of either writer (the book is fairly pro-Babitz, often at Didion's expense); anyone who has the Lit Hub Didion tote bag. —SMS

The Endless Refrain by David Rowell [NF]

What it's about: How the rise of music streaming, demonitizing of artist revenue, and industry tendency toward nostalgia have laid waste to the musical landscape, and the future of music culture.

Who it's for: Fans of Kyle Chayka, Spence Kornhaber, and Lindsay Zoladz. —SMS

Every Arc Bends Its Radian by Sergio De La Pava [F]

What it is: A mind- and genre-bending detective story set in Cali, Colombia, that blends high-stakes suspense with rigorous philosophy.

Who it's for: Readers of Raymond Chandler, Thomas Pynchon, and Jules Verne. —SMS

Something Close to Nothing by Tom Pyun [F]

What it’s about: At the airport with his white husband Jared, awaiting a flight to Cambodia to meet the surrogate mother carrying their adoptive child-to-be, Korean American Wynn decides parenthood isn't for him, and bad behavior ensues.

Who it’s for: Pyun’s debut is calculated to cut through saccharine depictions of queer parenthood—could pair well with Torrey Peters’s Detransition, Baby. —NodB

Rosenfeld by Maya Kessler [F]

What it is: Kessler's debut—rated R for Rosenfeld—follows one Noa Simmons through the tumultuous and ultimately profound power play that is courting (and having a lot of sex with) the titular older man who soon becomes her boss.

Who it's for: Fans of Sex and the City, Raven Leilani’s Luster, and Coco Mellor’s Cleopatra and Frankenstein. —DF

Lazarus Man by Richard Price [F]

What it is: The former The Wire writer offers yet another astute chronicle of urban life, this time of an ever-changing Harlem.

Who it's for: Fans of Colson Whitehead's Crook Manifesto and Paul Murray's The Bee Sting—and, of course, The Wire. —SMS

Stranger Than Fiction by Edwin Frank [NF]

What it is: An astute curveball of a read on the development and many manifestations of the novel throughout the tumultuous 20th century.

Who it's for: Readers who look at a book's colophon before its title. —JHM

Letters to His Neighbor by Marcel Proust, tr. Lydia Davis

What it is: A collection of Proust’s tormented—and frequently hilarious—letters to his noisy neighbor which, in a diligent translation from Davis, stand the test of time.

Who it's for: Proust lovers; people who live below heavy-steppers. —DF

Context Collapse by Ryan Ruby [NF]

What it is: A self-proclaimed "poem containing a history of poetry," from ancient Greece to the Iowa Workshop, from your favorite literary critic's favorite literary critic.

Who it's for: Anyone who read and admired Ruby's titanic 2022 essay on The Waste Land; lovers of poetry looking for a challenge. —SMS

How Sondheim Can Change Your Life by Richard Schoch [NF]

What it's about: Drama professor Schoch's tribute to Stephen Sondheim and the life lessons to be gleaned from his music.

Who it's for: Sondheim heads, former theater kids, end of list. —SMS

The Serviceberry by Robin Wall Kimmerer [NF]

What it is: 2022 MacArthur fellow and botanist Kimmerer, an enrolled member of the Citizen Potawatomi Nation, (re)introduces audiences to a flowering, fruiting native plant beloved of foragers and gardeners.

Who it’s for: The restoration ecologist in your life, along with anyone who loved Braiding Sweetgrass and needs a nature-themed holiday gift. —NodB

My Heart Belongs in an Empty Big Mac Container Buried Beneath the Ocean Floor by Homeless [F]

What it is: A pseudonymous, tenderly comic novel of blue whales and Golden Arches, mental illness and recovery.

Who it's for: Anyone who finds Thomas Pynchon a bit too staid. —JHM

Yoke and Feather by Jessie van Eerden [NF]

What it's about: Van Eerden's braided essays explore the "everyday sacred" to tease out connections between ancient myth and contemporary life.

Who it's for: Readers of Courtney Zoffness's Spilt Milk and Jeanna Kadlec's Heretic. —SMS

Camp Jeff by Tova Reich [F]

What it's about: A "reeducation" center for sex pests in the Catskills, founded by one Jeffery Epstein (no, not that one), where the dual phenomena of #MeToo and therapyspeak collide.

Who it's for: Fans of Philip Roth and Nathan Englander; cancel culture skeptics. —SMS

Selected Amazon Reviews by Kevin Killian [NF]

What it is: A collection of 16 years of Killian’s funniest, wittiest, and most poetic Amazon reviews, the sheer number of which helped him earn the rarefied “Top 100” and “Hall of Fame” status on the site.

Who it's for: Fans of Wayne Koestenbaum and Dodie Bellamy, who wrote introduction and afterword, respectively; people who actually leave Amazon reviews. —DF

Cher by Cher [NF]

What it is: The first in a two-volume memoir, telling the story of Cher's early life and ascendent career as only she can tell it.

Who it's for: Anyone looking to fill the My Name Is Barbra–sized hole in their heart, or looking for something to tide them over until the Liza memoir drops. —SMS

The City and Its Uncertain Walls by Haruki Murakami, tr. Philip Gabriel [F]

What it is: Murakami’s first novel in over six years returns to the high-walled city from his 1985 story "Hard-Boiled Wonderland and the End of the World" with one man's search for his lost love—and, simultaneously, an ode to libraries and literature itself.

Who it's for: Murakami fans who have long awaited his return to fiction. —DF

American Bulk by Emily Mester [NF]

What it's about: Reflecting on what it means to "live life to the fullest," Mester explores the cultural and personal impacts of America’s culture of overconsumption, from Costco hauls to hoarding to diet culture—oh my!

Who it's for: Lovers of sustainability; haters of excess; skeptics of the title essay of Becca Rothfeld's All Things Are Too Small. —DF

The Icon and the Idealist by Stephanie Gorton [NF]

What it is: A compelling look at the rivalry between Margaret Sanger, of Planned Parenthood fame, and Mary Ware Dennett, who each held radically different visions for the future of birth control.

Who it's for: Readers of Amy Sohn's The Man Who Hated Women and Katherine Turk's The Women of NOW; anyone interested in the history of reproductive rights. —SMS

December

Rental House by Weike Wang [F]

What it's about: Married college sweethearts invite their drastically different families on a Cape Code vacation, raising questions about marriage, intimacy, and kinship.

Who it's for: Fans of Wang's trademark wit and sly humor (see: Joan Is Okay and Chemistry); anyone with an in-law problem.

Woo Woo by Ella Baxter [F]

What it's about: A neurotic conceptual artist loses her shit in the months leading up to an exhibition that she hopes will be her big breakout, poking fun at the tropes of the "art monster" and the "woman of the verge" in one fell, stylish swoop.

Who it's for: Readers of Sheena Patel's I'm a Fan and Chris Kraus's I Love Dick; any woman who is grateful to but now also sort of begrudges Jenny Offil for introducing "art monster" into the lexicon (me). —SMS

Berlin Atomized by Julia Kornberg, tr. Jack Rockwell and Julia Kornberg [F]

What it's about: Spanning 2001 to 2034, three Jewish and downwardly mobile siblings come of age in various corners of the world against the backdrop of global crisis.

Who it's for: Fans of Catherine Lacey's Biography of X and Joshua Cohen's The Netanyahus. —SMS

Sand-Catcher by Omar Khalifah, tr. Barbara Romaine [F]

What it is: A suspenseful, dark satire of memory and nation, in which four young Palestinian journalists at a Jordanian newspaper are assigned to interview an elderly witness to the Nakba, the violent 1948 expulsion of native Palestinians from Israel—but to their surprise, the survivor doesn’t want to rehash his trauma for the media.

Who it’s for: Anyone looking insight—tinged with grim humor—into the years leading up to the present political crisis in the Middle East and the decades-long goal of Palestinian autonomy. —NodB

The Shutouts by Gabrielle Korn [F]

What it's about: In the dystopian future, mysteriously connected women fight to survive on the margins of society amid worsening climate collapse.

Who it's for: Fans of Korn's Yours for the Taking, which takes place in the same universe; readers of Becky Chambers and queer-inflected sci-fi. —SMS

What in Me Is Dark by Orlando Reade [NF]

What it's about: The enduring, evolving influence of Milton's Paradise Lost on political history—and particularly on the work of 12 revolutionary readers, including Malcom X and Hannah Arendt.

Who it's for: English majors and fans of Ryan Ruby and Sarah Bakewell—but I repeat myself. —SMS

The Afterlife Is Letting Go by Brandon Shimoda [NF]

What it's about: Shimoda researches the mass incarceration of Japanese Americans during WWII, and speaks with descendants of those imprisoned, for this essay collection about the “afterlife” of cruelty and xenophobia in the U.S.

Who it’s for: Anyone to ever visit a monument, museum, or designated site of hallowed ground where traumatic events have taken place. —NodB

No Place to Bury the Dead by Karina Sainz Borgo, tr. Elizabeth Bryer [F]

What it's about: When Angustias Romero loses both her children while fleeing a mysterious disease in her unnamed Latin American country, she finds herself in a surreal, purgatorial borderland where she's soon caught in a power struggle.

Who it's for: Fans of Maríana Enriquez and Mohsin Hamid. —SMS

The Rest Is Silence by Augusto Monterroso, tr. Aaron Kerner [F]

What it is: The author of some of the shortest, and tightest, stories in Latin American literature goes long with a metafictional skewering of literary criticism in his only novel.

Who it's for: Anyone who prefers the term "palm-of-the-hand stories" to "flash fiction." —JHM

Tali Girls by Siamak Herawi, tr. Sara Khalili [F]

What it is: An intimate, harrowing, and vital look at the lives of girls and women in an Afghan mountain village under Taliban rule, based on true stories.

Who it's for: Readers of Nadia Hashimi, Akwaeke Emezi, and Maria Stepanova. —SMS

Sun City by Tove Jansson, tr. Thomas Teal [F]

What it's about: During her travels through the U.S. in the 1970s, Jansson became interested in the retirement home as a peculiarly American institution—here, she imagines the tightly knit community within one of them.

Who it's for: Fans of Jansson's other fiction for adults, much of which explores the lives of elderly folks; anyone who watched that documentary about The Villages in Florida. —SMS

Editor's note: We're always looking to make our seasonal book previews more useful to the readers, writers, and critics they're meant to serve. Got an idea for how we can improve our coverage? Tell me about it at sophia@themillions.com.

[millions_email]

Turn the Page: Your Next Rock ‘N’ Roll Book Club

My wife carries the distinction of being, among many other things, the world’s most ardent fan of the southern California folk-rock band Dawes. If they’re playing a show within 100 miles of our home, she will unquestionably be there; when they announce the release of a new recording, she pre-orders it as soon as she can. And if they offer a book club -- in which, every other month, a member of Dawes sends out a paperback, along with an explanation of why he chose that book -- she will become a member, excessive cost be damned. Since she joined in August, we’ve received three Dawes-approved titles: Italo Calvino’s If on a Winter’s Night a Traveler, Ken Kesey’s Sometimes a Great Notion, and, most recently, Henry Miller’s Big Sur and the Oranges of Hieronymus Bosch. “[Miller] leans heavily on some of the pre-existing tenets of eastern religion,” drummer Griffin Goldsmith writes in his “Dawes Book Report,” “particularly the idea that an individual’s happiness is not only contingent upon where they are in the world, but also upon a confluence of internal emotions.”

To put it mildly, such knottiness is not what my wife expected from her fluffy-haired purveyors of golden-hued singalongs. (And I can’t really blame her; in college, I abandoned Sometimes a Great Notion after 15 flummoxing, headache-inducing pages.) All I can do is clear out shelf space for her new and difficult books -- and suggest, politely, that she join one of the following competing rock 'n' roll reading clubs, which, of course, include their own book reports.

Ozzy Osbourne: Of Mice and Men

So, Of Mice and Men, it’s got this big dumb wanker, Christ, I can’t remember his name -- wait, wait, it’s Denny, no, Lenny, that’s it -- and his mate, this teensy little shitter, George. This George fellow is like the Oates to Lenny’s Hall, if that makes any sense. I don’t think it does. Fucking “Maneater,” innit. Anyway, they’re all kinda walking around and what, like, camping? And the big one, he’s always killing the animals ‘cos he’s so fucking big. Like, you ever see that guy, whatsit, Joey Ramone? I met him once in Boston, or like Tokyo? He was fuckin’ huge, and that’s who I kept thinking of when I was reading this book. At the end of the book, the guy from the Ramones kills this kind of hooker-type bird in a barn, and that was pretty much that. Christ, I don’t know what this book was on about.

Bob Dylan: Twilight

Twilight is a book about a girl who falls in love with a boy who, I’ll tell you right now, just happens to be a vampire. Life is funny like that sometimes. But this girl, her name is Bella. And she can’t do anything about this love of hers; she just can’t put it through. Some hoodoo about magic powers, is what I’m gathering. Young love is like that, I’ve found -- untrustworthy at its heart and cold where it shouldn’t be. The book asks a certain kind of question, one that the wise men have been wrestling since the days of Plato, since the days of Little Richard, banging out his mystic sounds: is true love possible? And if not, how about vampire love? Now, I don’t know if it is or not, since I never was able to finish the book. I couldn’t make hide nor hair of it, to be honest on all fronts. It’s really long -- longer than the mighty Mississippi, where you can hear that steam whistle blow, far off into the night. Out beyond them sycamore trees standing out in the dark. A sound to scare the vampires, if there are any vampires around to scare.

Jimmy Buffett: American Psycho

Maybe you weren’t expecting Bret Easton Ellis’s American Psycho to be the first selection of my book club. Jimmy, I hear you plead, you’re the bard of the beachfront, the Wordsworth of the waves. You once released an album called License to Chill; you write songs about delicious cheeseburgers. Why kick things off with a harrowing, full-bore descent into the savage, blood-spattered heart of our long-dead modern dream? Why confront us with this jagged, debauched journey into a pornographic, torturous vision? Why not give us something easy, something by Carl Hiaasen or, you know, Dave Barry -- or better yet, one of your own books, like the lounge-chair-ready A Salty Piece of Land or Where is Joe Merchant?

My response is this, my faithful Parrotheads: beneath every placid exterior lies a festering, maggot-ridden core, a hellish pit of snakes and raw-boned, scalding pain. Stare into those waves lapping gently against the shore long enough, and soon enough you’ll see the nihilism in their relentless pounding; that water at your sunburned feet should remind us all of the steady encroachment of death.

Anyway, where was I? Oh, yes -- I hope you dig the book! Up next after this one: The Lincoln Lawyer, by Michael Connelly!

Adam Levine: Ulysses

Hey, Maroon 5 Book Clubbers! This month’s super-cool novel is James Joyce’s Ulysses, which is hugely important to me, and not just because it’s the most prominent landmark in modernist literature -- or that in 1998 the Modern Library named it the best English-language novel of the 20th Century! I chose Ulysses because it’s a work in which life’s complexities are depicted with unprecedented, and unequalled, linguistic and stylistic virtuosity. (Seriously, guys, it is!) But that’s not all: in its characters we see, according to some lex eterna, an ineluctable condition of their very existence! Isn’t that rad? All right now, Fivers, get to it -- I hope you love it as much as I did! ‘Cause I totally read it -- and other books, too! I didn’t just have my assistant cut and paste lines from Wikipedia to make it seem like I had read Joyce’s sublime masterpiece, which, I have to say, depicts life's complexities with unprecedented, and unequalled, linguistic and stylistic virtuosity!

Image Credit: Wikipedia/jon rubin.

Fifty Shades of Sociological Commentary

In her new book, Hard-Core Romance, Eva Illouz has published the first serious, book-length academic analysis of the Fifty Shades of Grey. The critically-panned Fifty Shades trilogy, originally a Twilight fan fiction, has sold 32 million copies in the US so far. At The New Republic, William Giraldi seizes the opportunity for a brutal send-up of author E. L. James and the “dreck” she represents. "At least people are reading,” he writes, “You’ve no doubt heard that before. But we don’t say of the diabetic obese, At least people are eating.” Pair with The Millions’ essay on literary predecessors in published fan fiction.

Nathaniel P. Gets the Fanfic Treatment: On Adelle Waldman’s “New Year’s”

Among its many other splendors, the Web has created a market for a strain of ancillary fiction that takes the characters and themes of an existing story - George Lucas's Star Wars, say, or Stephenie Meyer's Twilight - and creates a new story designed to shed light on the existing one. Fan fiction, it's called. So far, fan fiction has focused mostly on genre stories, especially sci-fi and fantasy, but there's no reason literary fiction can't have its own fan fiction - and perhaps the quickest way to kick off the trend would be for literary authors to write a little fanfic of their own.

To a certain degree, this appears to be what has happened with the publication of Adelle Waldman’s “New Year’s,” a Kindle Single timed for the paperback release of her 2013 breakout novel The Love Affairs of Nathaniel P. "New Year's" is a fully rendered work of literary fiction, just short of novella length, but the story, helpfully subtitled, “Nathaniel P. as Seen Through the Eyes of his Friend Aurit,” almost certainly wouldn’t exist, at least not in this form, were it not for the paperback release of Nathaniel P. Genre writers have been releasing these add-on stories for some time now, but this is among the first I have seen from a literary author, and it’s illuminating, both in terms of the risks a talented writer takes in rushing out a story to meet an artificial deadline, and more broadly, as an object lesson in the risks writers face when the traditional obstacles to publishing a work of fiction fall away.

I am, for the record, an admirer of Waldman’s writing and of Nathaniel P., though I recognize it isn’t for everybody. Waldman’s characters live in certain self-consciously liberal neighborhoods in Brooklyn and are nearly all upper-middle-class, attractive, well-educated, and to some degree freakishly successful in the arts. There are people out there, one is given to understand, who are not quite so lucky in their intellectual capacities or their socio-economic circumstances – a phenomenon Waldman’s characters respond to by writing sympathetic essays, which they hope will land in prestigious magazines and further their careers.

Waldman’s fictive universe is, in short, a bit hard to take. But she possesses a rare gift for dramatizing psychological insight, and in Nathaniel P., her first novel, she focuses on Nate Piven, a thirty-year-old novelist, who like so many young Brooklyn artists, lives in mortal terror of having to one day grow up. In Nate’s case, this terror takes the form of an abiding fear of commitment in romantic relationships – which, after all, lead inevitably to marriage and children – and in the pages of the book, we watch Nate skillfully manipulate a girlfriend into breaking up with him.

It’s riveting in its way, especially since Waldman is so good at exploring the ways intelligent people can be so blind to their own monstrousness. In “New Year’s,” Waldman’s emotional radar remains quiveringly intact, but the story itself is as slack and shapeless as a Sunday morning at a Brooklyn coffee house. The plot, such as it is, turns on whether Nate and Aurit, an Israeli-born writer who was a minor character in the original novel, will become a couple. But Waldman seems only intermittently interested in this central narrative, and instead fills page after page with backstory about Aurit’s school years, which too often reads like one of those background histories actors write for themselves to help them get into character.

We learn, in excruciating detail, how after her family’s immigration from Israel, Aurit was desperate to fit in with the crowd at her suburban Boston middle school, but clueless about fashion and American pop culture, found herself passed over by her classmates who saw her as hopelessly “bespectacled, bookish, [and] brown-skinned.” Later, thanks to some savvy clothing and hair choices, Aurit pulls off a “punk-inspired asexual, alternative look,” and following a pre-college weight loss, she acquires an actual boyfriend. None of this is unconvincing as social detail, nor does it make Aurit seem less worthy a subject for fictional treatment, but it does make one hanker for the, um, story to begin.

When it finally does, it’s over before the reader has a chance to savor it. While hanging out together after a New Year’s party, Nate tells Aurit, “You give me feedback I don’t get anywhere else.” This is as close as a man like Nate comes to a statement of undying love, and it gives Aurit reason to think they might become more than friends. Then, all too quickly he returns to form, an overgrown man-child incapable of a mature relationship with a woman – and we’re done.

What’s most maddening about this is that, setting aside that long dry spell about Aurit’s teen angst, there is a kernel of a great story here about the difference between romantic love and the platonic kind. Everyone has had a close relationship that works better as a friendship than as a romance, and at some half-drunken moment of intimacy, everyone has wondered why. “New Year’s” seems a story poised to answer this very human question, and then, for some reason, it simply doesn’t.

Writing great fiction is a little like hitting Major League pitching – even the best in the game fail to get a hit seven times out of ten. But here one can’t help wondering if the ease of its publication may not have also played a role in the story’s failure to fully engage. In an analog world, Waldman might well have wanted to tell a story from the perspective of a minor character that provided insight into the protagonist of her recently published novel – to write a bit of self-initiated fan fiction, as it were – but she would have faced some thorny logistical problems.

For one thing, virtually no one publishes stand-alone novellas in print. Perhaps Waldman could have trimmed it to a more standard story length – pruned some of that backstory about Aurit’s formative years, say. But even then she would have had to find a literary journal willing to take the story on its own terms, not merely as an online add-on to a paperback release, or she would have had to wait until she had enough other publishable stories to make a full collection.

It is unwise, of course, to make too much of one misbegotten story. We are still in the experimentation phase with Web-only publication, and the point of experiments is that they don’t always work. One can only imagine what a restless mind like William Faulkner’s would make of a world in which an author wishing to fill in extra detail about an existing literary world need only write up the story, slap a title on it, and post it to the web.

At the same time, though, when it comes to literary fiction, perhaps we should be mindful of the special demands of print. The cost of printing and distributing physical books has never stopped bad books from being published, but it does raise the barrier to entry. It creates an intermediary rank of editors, agents, and publishers whose job it is to be rigorous with authors, forcing them to make their work as strong as it can possibly be. If the Web is the future of fiction – and how can it not be? – we don’t want to stifle innovation. Still, it’s a mistake to make it too easy for writers to reach readers, because part of what makes a story good is how many hurdles it has had to jump before it finds its way to a reader’s hands.

Teaching the ‘Law and Order’ Short Story

At the beginning of each semester, I gather basic information from my fiction writing students such as major, hometown, and favorite book. Some of this arrives from the registrar before the semester begins, but the information isn’t always accurate, and many students accustomed to large, impersonal classes appreciate even perfunctory interest in their lives. My students’ majors are varied, and the students come from all over the world, even at a state university. With few exceptions, their book selections are depressing.

The selections are not depressing because the books are sad. That would be great. I mean depressing as in uninspired, as in the last book the students can remember reading in high school, the book a movie was based on (sometimes they have only seen the movie), the Twilight series or Hunger Games series. Pretty much any series. This semester three students picked Lord of the Flies and three picked Harry Potter, edging “no response” as the most popular titles. It’s not that these books are necessarily bad, though some are. Instead, it’s what these choices suggest to me, that books occupy an ancillary role in the students’ lives. Books are something they had to read in class, or something a movie is based on, a movie everyone else is seeing. The book is rarely the thing the student willingly came to first.

Although my students and I infrequently read the same books, we watch some of the same television shows. We’re more likely to find common ground discussing Breaking Bad than Yiyun Li. If I watched Game of Thrones or The Walking Dead, we’d have a lot to talk about because those programs influence their writing more than any author, living or dead. Other influences: CSI (in its various locales), Law and Order (in its various incarnations), True Blood (vampire everything). I’m not trying to be glib or cute. These are the narratives that influence students’ writing. It’s something I need to take seriously.

Who am I to determine what’s good or bad? That’s a reasonable question. Isn’t it my job, as possibly the only creative writing instructor these students will ever have, to place moving stories into their hands, instill the virtues of reading, caution them against the culture’s basest offerings? Yes, gladly. But that’s not the question I find myself asking. The question isn’t even how to teach writing to students who don’t read. The question is how to teach writing to students who watch movies and television instead of reading.

This class, I should note, is an upper-level elective. All of my students arrive voluntarily, and most are upperclassmen. My classes are unfailingly populated with curious young men and women. They’re earnest and respectful and hard-working. I genuinely like them. Every fall and spring there is a waitlist because students want to write stories. What they don’t particularly want to do is read them. Reading literary fiction for the pleasure or edification of reading literary fiction is something very few of my students do.

What they reliably do is watch movies and television. I’m not sure if I’ve encountered a student who doesn’t. When I was in college — this is the last time I’ll allow myself this indulgence — I remember few conversations about television and little time spent watching it. There was a TV in the communal lounge, but it was a shabby space relative to the temptations elsewhere. To be fair, television has improved since I was a student. David Chase’s The Sopranos and David Simon’s The Wire, everyone seems to agree, raised the bar for what a television show could be. One can debate Simon’s characterization of The Wire as a “visual novel,” but for some of my students, it’s the only novel they choose to consume.

I have my students read a lot of stories. I make a point, as most instructors do, to vary the subjects and styles, to include authors of different ages, ethnicities, genders, classes, and backgrounds. Every two years I change all of the stories, so I’m not flying on autopilot. There is no shortage of incredible short fiction. The students digest the stories dutifully. Sometimes students are visibly moved in class, which visibly moves me. These mutually-moved moments don’t happen all of the time. I’ve learned to appreciate them.

When a student really likes a story, she will often compare it to a favorite episode, and then this happens:

“It totally reminds me of the Dexter when he —”

“Oh my God, I’m obsessed with that show.”

(General murmurs of approval.)

“Have you seen the one where he [kills someone in a mildly unpredictable way for morally dubious reasons]?”

“That one is amazing.”

Nobody says she is obsessed with Denis Johnson.

My students love Dexter. I have watched enough episodes to conclude I do not love Dexter, though it’s an interesting case study, as it attempts to communicate the protagonist’s inner life. This is harder to do on the screen than on the page, and while I applaud the show’s writers for taking this aspect seriously, the character’s monologues strike me as clumsy and inorganic. They’re supposed to be funny, but they’re not funny.

I have yet to find a voiceover that doesn’t make me cringe. As great as Vertigo is, the voiceover bums me out every time. I feel like Hitchcock doesn’t trust me — or his filmmaking — enough, and I’m thrown out of what John Gardner calls the “vivid and continuous dream.” If American Hustle wins a bunch of academy awards, it will be in spite of the lazy voiceover.

Good fiction grants you sustained, nuanced entry into a character’s mind that is difficult to achieve on the screen. This is one of the reasons the best books rarely translate into transcendent films, no matter how many times studios try (e.g. The Great Gatsby). It’s also why some of the best films come from books that aren’t universally regarded (e.g. The Godfather). That The Godfather works better as a film than a book doesn’t diminish the story. Film and literature aren’t interchangeable, and watching the former isn’t necessarily going to help you write the latter. Indeed, it may give you some bad habits. In the classroom, I regularly find myself contradicting the students’ first teacher, the screen.

Each Law and Order episode begins with the short dramatization of a crime. Those two minutes set the tone for the rest of the hour. The showrunner makes a contract with the audience before each episode: There will be a crime, it will be investigated, there will be red herrings, but the crime will be solved. Although the characters are more or less the same from episode to episode, the crimes are self-contained. Clearly, this formula works. It’s hard to find someone who hasn’t enjoyed an episode of Law and Order. I particularly enjoy the halcyon days of Special Victims Unit with Christopher Meloni, Mariska Hargitay, Ice-T, and BD Wong, whom I regard as a master of deadpan.

What I don’t enjoy are short stories inspired by SVU. Meloni and Hargitay are fine actors, but on the show, their inner lives are straightforward. They’re driven by primal and singular impulses. The world they inhabit offers little complexity. Sex offenders are bad. Detectives are good. Sometimes good people have to do bad things to get bad guys; that’s about as morally ambiguous as the show gets. It also has a fetish for vigilantism that I don’t share.

One of the most common student stories begins with a scene of violence. It’s unclear who is involved, or why they’re doing what they’re doing. Typically, nobody is named. There’s a space break signifying a leap in time and place, and then the story unfolds in a linear fashion. By the end, the villain (easier to spot than the writer imagines) is apprehended, often with a bit of insufferable banter. The story doesn’t work. My students didn’t learn this formula from reading.

I reference the stories we read. Look where Raymond Carver starts his story. What is all of the protagonist’s furniture doing on the front lawn? Why does Mary Robinson have the strange woman stop by the house on the second page? Start the story as late in the action as you can, I tell my students. Make sure your protagonist wants something, even if only a glass of water. I tell them Kurt Vonnegut gave me this advice. Some of them read Slaughterhouse Five in high school. We’re getting somewhere. Did you read any of his other books? Blank stares.

Ideally, the stories I assign and recommend will lead my students to read fiction on their own. Sometimes this happens. They take other classes with me, stop by my office hours, write me emails. Few things make me happier than students from past semesters soliciting books. I hope they’re still writing, but if they’re only reading, they’re enlarging their sense of human experience. They’re becoming more empathetic and, in turn, better brothers and sisters, sons and daughters, boyfriends and girlfriends. I believe this.

Most students I never hear from again. We get fifteen weeks, twice a week, eighty minutes a class. It’s not a lot of time to inspire a lifetime of reading. It’s not a lot of time to give students a framework from which they might begin to construct meaningful stories on their own.

Each student writes two stories for my class, but the time he or she spends thinking about the published stories I assign is arguably more important. Students who haven’t taken many writing or literature classes at the university will likely arrive with few reference points, and I treat each story as an opportunity to teach students about character or structure or language. When students reference television shows, I counter with stories. If the story isn’t protected by copyright, I’ll post a link to Blackboard. Anyone can read Anton Chekhov’s “Gusev” or James Joyce’s “Araby” or Alice Munro’s “The Bear Came Over the Mountain” for free online. Publishers mail me unsolicited books all of the time; I give the good ones to my students.

Sometimes when students reference television shows, I go with it. I ask students what they like about the show and what, if anything, they might apply to their writing. If I admire the film they reference, and I think it offers something narratively rewarding, we discuss why. Occasionally, I reference a moment in a film, for better or worse. The Third Man delays the introduction of the antagonist in a way that’s supremely effective (it doesn’t hurt that Graham Greene wrote the screenplay). I rather like Lost in Translation, but the scene where Bill Murray whispers something unheard to Scarlett Johansson strikes me as a narrative betrayal. The writer and character, I’ve told them, shouldn’t know more than the reader. Like all teachers, I’m happy when students intelligently disagree.

In their own stories, I encourage students to write something that makes them uncomfortable. If they’re going to write autobiographically, and many do, they have to be prepared to show their worst characteristics. Probably, the protagonist should do something stupid or ugly. That’s what the reader wants. If they’re going to make something up completely, and I encourage this, they have to move beyond formula. If they crib a violent scene from The Walking Dead, I give them Flannery O’Connor. It’s no less gruesome.

My students are curious in my own tastes, to an extent. What do I like to watch? I tell them. I pair the film with a book. They want to know why the book is always better than the movie. They’re referring to Harry Potter or The Hunger Games. They’ve been told this so many times they believe it, even if they don’t see it personally. It’s because your imagination is so much more interesting than what’s on the screen, I tell them. They don’t buy it. Their interest wanes. The reader and the writer co-create the story, I insist. Reading is collaborative in a way that watching a screen isn’t. You prefer your image to the director’s, no matter how beautiful Jennifer Lawrence might be. You’re narcissistic that way. It’s okay.

They nod reluctantly, like maybe it is.

Reasons Not to Self-Publish in 2011-2012: A List

In a previous essay, I interviewed four self-published authors I admire, and I examined some of the benefits of that career path. Midway through writing the piece, I realized I'd have to continue the discussion in a second essay in order to fully explore my feelings (complicated) on the topic (multifaceted). You see, Reader, I still don't plan on self-publishing my first novel, though I don't deny the positive aspects of that choice.

Below I've outlined a few reasons behind my decision, informed by our contemporary moment. I can't predict the future, though I'm sure I'll remain comfortable with my opinions for at least another thirteen months. It's in a list format, the pet genre of the blogosphere. How else was I to keep my head from imploding?

1. I Guess I'm Not a Hater

People love to talk about how traditional publishing is dying, but is that actually true? According to The New York Times, the industry has seen a 5.8% increase in net revenue since 2008. E-books are "another bright spot" in the industry, and the revenue of adult fiction grew by 8.8% in three years. (Take that, Twilight!)

Of course, the industry has troubles. The slim profit margins of books; the problems of bookstore returns; the quandary of Borders closing and Amazon forever selling books as a loss-leader; how to make people actually pay for content, and so on. Furthermore, the gamble of the large advance strikes me as ridiculous -- and reckless, considering that editors and marketing teams have no real clue which books will be hits and which ones won't. (Still, what writer is going to kick half-a-million out of bed?) And there's the always-chilling question: With mounting pressure to turn a profit, how do editors justify publishing an amazing book that might not speak to a large audience? Talented authors -- new and mid-list -- are bound to get lost in this system.

And yet. And yet. I read good books by large publishing houses all the time, books that take my breath away, make me laugh and cry and wonder at the brilliance of humanity. I trust publishers. They don't always get it right, but more often than not, they do. As I said in the piece that started me off on this whole investigation: "I want a reputable publishing house standing behind my book; I want them to tell you it’s good so that I don’t have to."

2. I Write Literary Fiction

Before you get your talons out, let me clarify: I don't consider literary fiction superior to other kinds of fiction, just different; to me, it's simply another genre, subject-wise and/or marketing-wise. Many of the writers who have found success in self-publishing are writers of straightforward genre fiction. Amanda Hocking writes young adult fantasy, dwarfs and all. Valerie Forster, who published traditionally before setting out on her own, writes legal thrillers. Romance, too, often does just fine without a publisher. Aside from Anthropology of An American Girl by Hilary Thayer Hamann, I can't think of another literary novel that enjoyed critical praise and healthy sales when self-published. That's not to say that it can't -- and shouldn't -- happen, it's only to point out that it's a tougher road for writers of certain sorts of stories. Readers like me aren't seeking out self-published books. Why not? That's for another essay. (Please, can someone else write that one?) Until the likes of Jeffrey Eugenides and Alice Munro begin publishing their work via CreateSpace, I don't see the landscape for literary fiction changing anytime soon.

3. I'd Prefer a Small Press to a Vanity Press

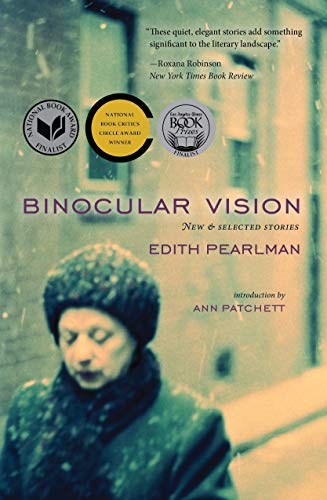

The conversation about self-publishing too often ignores the role of independent publishing houses in this shifting reading landscape. Whether it be larger independents like Algonquin and Graywolf, or small gems like Featherproof and Two Dollar Radio, or university presses like Lookout Books, the imprint at the University of North Carolina, Wilmington, which recently published Edith Pearlman's Binocular Vision (nominated for this year's National Book Award), independent presses offer diversity to readers, and provide yet another professional option for authors. These presses are run and curated by well-read, talented people, and they provide readers with the same services that a large press provides: namely, a vote of confidence in a writer the public might have never heard of. Smaller presses, too, enjoy a specificity of brand and identity that too often eludes a larger house.

In this terrific interview, publisher Fred Ramey of Unbridled Books puts it this way:

I believe that the iron grip that large publishers and their marketing partners have had on readers' attention since the 1990s has slipped quite a bit with the arrival of online retailers and opinion-makers. Obviously patrons of online booksellers can see the breadth of reading options - "Others who bought this item also bought...." Patrons of independent bookstores know of those options, too, and depend on the recommendations of their booksellers. The few "designated" titles from the big house are still dominant, of course, even in independent stores. But if you are an author in one of those corporations whose book has not been "designated" your reality can become pretty stark.

Independent presses can offer a real chance to a talented writer who might not fit the formulas of the big house. Yes, I know that each conglomerate has a few imprints and a good many editors dedicated to the best of books -- to maintaining the course of American letters. Those are the prestigious imprints that aren't always required to pretend the sales of a prior book predict the performance of the next book. (I'm often astounded at how willing the industry is to act as though it believes that. We all know it isn't true.) But independent presses are all dedicated to finding and presenting the best of books, dedicated to the books in and of themselves and to the promise of the authors.

A year ago, I published my novella If You're Not Yet Like Me with a tiny press called Flatmancrooked, and I consider it the highlight of my career so far. Not only did I get to work with a sharp and talented editor, Deena Drewis, and have my book designed by the press's risk-taking founder Elijah Jenkins, I also had so much fun participating in the press's LAUNCH program, where the limited first-edition went on pre-order for just a week. My book sold out in three days, and getting that first paycheck was exhilarating. My tiny book got me on a panel at the Los Angeles Times Festival of Books, a few awesome readings, and it even found its way to two different editors at larger houses. It became my literary calling card. When readers received my book in the mail, it was signed and numbered by me. It also came with a condom.

Flatmancrooked, sadly, closed its doors earlier this year, but Drewis has continued the LAUNCH program with her new press, Nouvella. The success of Flatmancrooked showed me that small can mean flexible and daring in its editorial and marketing choices. Small presses try things that large, established houses are too huge, and possibly too chickenshit, to even consider. The fact that Flatmancrooked is now defunct showed me that a labor of love is still a labor (especially when its laborers have other full-time jobs to go to), and that instability is unavoidable in the small press (or the small, small, small press) game.

Some writers are forever wed to the small press landscape. Others, like Blake Butler, Amelia Gray, Benjamin Percy, and Emma Straub first published with smaller outfits and have since moved onto larger houses. Perhaps the small press world is becoming the real proving ground for literary writers.

4. Self-Publishing is Better for the Already-Published

Perhaps the smarter, and far more seductive, path is the one where the writer begins his career with a traditional publisher, and then, once he's built a base of loyal readers, sets off on his own. The man who loves to talk smack about the publishing industry, J.A. Konrath, already had an audience from his traditionally-published books by the time he decided to take matters into his own hands. It's much harder to create a readership out of nothing.

I'm interested to see how Neal Pollack's latest novel, Jewball, does as a self-published book. Short story writer Tod Goldberg is also trying this approach with his new mini-collection, Where You Lived, self-published as an e-book. I don't need an intermediary to tell me about these writers because their previously published books speak for them.

5. I Value the Publishing Community

I decided to ask the most famous writer I know, Peter Straub, if he's ever considered leaving the world of big publishing and putting out a book all by his lonesome. After all, he's a bestselling author and editor of more than 25 books (18 novels alone!), and he's a horror writer beloved by genre geeks and snobby literary types alike. A few of his fans probably sport tattoos of his bespectacled face on their pecs. (Or: Peter Straub tramp stamps! Yes!) In an email response, Straub acknowledged how quickly the publishing world and our reading habits are changing, and he said he just might experiment with self-publishing short fiction in the coming years. He told me:

True self-publication means writers upload content themselves, and plenty already do it. I'm not quite sure how you then publicize the work in question, or get it reviewed, but that I am unsure about these elements is part of the reason I seek always, at least for the present, to have my work published in book form by an old-style trade publisher. The trade publisher, which has contracted for the right to do so, then brings the book out in e-form and as an audiobook, so I am not ignoring that audience.

What he went on to say gave me a special kind of hope:

Most of the editors I have worked with over the past thirty-five years have made crucial contributions to the books entrusted to them, and the copy-editors have always, in every case, done exactly the same. They have enriched the books that came into their hands. Can you have good, thoughtful, creative editing and precise, accurate, immaculate copy-editing if you self-publish? And if you can't, what is being said about the status or role of selflessness before the final form of the fiction as accepted by the audience, I mean the willingness of the author to submerge his ego to produce the novel that is truest to itself?

This -- this! -- I get. Even though my first novel was rejected by traditional publishers, one assistant editor's notes on it -- notes that were thorough, thoughtful, challenging, and compassionate -- were enough to show me that these professionals are valuable to the process of book-making. I know you can hire experienced editors and copy-editors, but how is that role affected when the person paying is the writer himself? What if the hired editor told you not to publish? Would that even happen?

6. The E-Reading Conundrum; or, I don't want to be Amazon's Bitch

Many self-published authors have gone totally electronic, eschewing print versions of their work altogether. I can't see myself taking that route, however, because I don't own an e-reader, and I don't have plans to buy one (not yet, anyway... I read a lot in the bath, etc., etc.). It seems odd that I wouldn't be able to buy my own book -- I mean, shouldn't I be my own ideal reader? I also prefer to shop at independent bookstores, and in fact, I pay full price for my books all the time. The thought of Amazon being the only place to purchase my novel shivers my timbers. I don't mind if someone else chooses to read my work electronically, just as I don't mind if Amazon is one of the places to purchase my work; I'm simply wary of Amazon monopolizing the reading landscape. Self-publishing has certainly offered an alternative path for writers, but it's naive to believe that a self-published author is "fighting the system" if that self-published book is produced and made available by a single monolithic corporation. In effect, they've rejected "The Big 6" for "The Big 1."

7. Is it Best for Readers?

In September, when my brother-in-law learned that my book still hadn't sold, he said, "Please don't self-publish!" He was actually wincing. If I did self-publish, he said, he'd buy it because we were family, but otherwise, he'd happily ignore my novel in search of something he'd read about on The Millions, or heard about on NPR, or had a friend recommend. There are simply too many books out there as it is.

Our conversation reminded me of Laura Miller's humorous and perspicacious essay, "When Anyone Can be a Published Author," in which she reminds us that the people who celebrate self-publishing often overlook what it means for book buyers and readers. She writes:

Readers themselves rarely complain that there isn’t enough of a selection on Amazon or in their local superstore; they’re more likely to ask for help in narrowing down their choices. So for anyone who has, however briefly, played that reviled gatekeeper role, a darker question arises: What happens once the self-publishing revolution really gets going, when all of those previously rejected manuscripts hit the marketplace, en masse, in print and e-book form, swelling the ranks of 99-cent Kindle and iBook offerings by the millions? Is the public prepared to meet the slush pile?

As a member of the reading public, I am not prepared, or willing, to wade through all that unfiltered literature. As a writer, I must put my head back to the grindstone and write a book that more than a handful of readers can fall in love with.

8. I'm Busy. Writing.

Today I wrote two pages of my new novel while my mother took my five-month-old son to the mall. I get twelve hours of childcare a week, and six of those are dedicated to preparing for my classes and running a private writing school. The other six hours I devote to my new novel. The old one, the one that traditional editors didn't go nuts for, is in the drawer. Some might say I've given up; I say, I'm just getting warmed up. I'm still writing, aren't I? My career isn't one book, but many. And like every other writer out there, I decide what road I want to travel.

Image credit: purplesmog/Flickr

Nobody Wants to Go Home: A Unified Theory of Reality TV

I.

In the 1990s, a scourge swept across the world of entertainment. It threatened the livelihoods of those in the creative industry and presented a world where the average person, dwelling in obscurity, could be plucked from the masses and made a star. It was equal parts thrilling and horrifying. No, I'm not talking about the internet, I'm talking about its cultural predecessor, reality television. Reality TV was supposed to devour television. It was going to make writers and actors irrelevant, and single-handedly lower the national reading level by two full grades. Reality television became shorthand for stupidity and quickly found a place as a scapegoat for one side or another of the culture war. These shows, with their cameras hidden and seen, were Orwellian nightmares come to life, Jean Beaudrillard essays in pixelated form. They were the beginning of the end of the world. Except that they weren't. They didn't really do any of the things they were feared to do. And yet, though their overall presence on the airwaves is a fraction what it was at their peak, their influence remains enormous.

We can say this now, from our perch in the shiny new decade. We've largely moved on to other fascinations, other distractions. We're scapegoating Twilight now, and we're all terrified of the internet. Or we're terrified of Twilight and scapegoating the internet. Paris Hilton has moved on to Twitter. We've all moved on to Twitter. But it wasn't too long ago when none of this seemed possible. It was a time before Lost, before The Wire, before the end. It was the glory days of reality television, and it all started on a cable network that had hours to fill, and little money with which to fill them.

II.

MTV wanted to make a soap opera. Like all the new cable networks, they had to fill the hours. America, it turned out, had an insatiable appetite for television, and the new cable networks were struggling to keep up. Some of them turned to re-runs of programs that had been modest hits in their original network incarnations -- the My Two Dads and Eight Is Enoughs of the world -- while others made cut-rate game shows and aired Just One of the Guys four times a day.

MTV had tried a few different things to kill time -- most notably, a twenty-year experiment in which they showed music videos in their entirety -- but had finally settled on a strategy of appealing to youth culture: the eternal fountain of disposable income. MTV's dilemma, however, was that, while it recognized that a soap opera would likely be popular and would round out its lineup of oversexed game shows and quasi-journalistic news programs, they lacked the funds to produce such a show. Their solution was brilliant -- they'd simply make a show without actors or writers -- two of the most expensive parts of any decent soap opera.

The result was The Real World, whose premise was neatly summed up in its introductory statement: "This is the true story of seven strangers picked to live in a house and have their lives taped to find out what happens when people stop being polite and start being real." That I can remember this sentence, awkward though it may be, with greater ease than I can The Pledge of Allegiance is testament to the incredible success of The Real World. Not only is it the longest running program in MTV's history (the network recently renewed the program for a 26th season), it created an entire category of programming and influenced some of the most successful shows on television today.

III.

The first two seasons of The Real World contain the seeds of all reality television, as well some elements that would find their way into today's most successful scripted programming. At first glance, the first season of The Real World appears to be a collection of random, diverse twenty-somethings thrown together in Manhattan. A closer look reveals that all of the cast members, from model/actor wannabe Eric Nies to writer/journalist Kevin Powell, aspired to a career in entertainment or the arts. The casting logic of the show was fairly simple: find some young people willing to try this experiment in exchange for some exposure. In this way, the cast member's situation wasn't unlike that of today's bloggers and vloggers -- they worked for free in exchange for an audience, presumably with the hope that the experience would translate into a career. For some it did; for others, not so much.

The first season of The Real World relied heavily on the pressures of their various careers for dramatic tension. We saw the characters balancing the time commitments of practice, rehearsal and performance with their newfound quasi-family unit back at the loft, a situation the young audience for the show could begin to appreciate. This balancing act -- with help from some racial tension -- blew up infamously when Kevin missed a group dinner meeting and was threatened with expulsion from the loft and the show. In the end, Kevin remained, but one could see that this episode, easily the most dramatic of the season, would not be an isolated incident in future iterations of the show.

Season two of The Real World is, arguably, the single most important season of any TV show of the last twenty years. It is one of those watershed moments that happens once or twice a generation. The first season of The Sopranos was such a moment. The third season of Mad Men, one could argue, was another. The second season of The Real World is so important because it revealed the flaws in the show's premise and, more importantly, several ways to work around those flaws. It provided, in a way, the template for all of the major reality TV shows to follow, though one could be forgiven for not realizing it at the time.

The second season took roughly the same premise as the first and moved it to Los Angeles, where it played up the aspirational angle a little bit more. Again we saw characters who desired fame and success -- singer Tami, comedian David, country singer Jon -- and again there was a healthy dollop of racial and sexual tension. This volatile mix exploded mid-season when David "assaulted" Tami, pulling a blanket off of her after she repeatedly asked him not to, revealing her in her underwear. For this crime -- something kids at camp do every summer -- David was forced out of the house and off the show entirely.

Several aspects of the controversy are worth noting. Firstly, the incident initially appeared to be a joke. While the house was somewhat divided over how serious it was (from where I stand, it's pretty clear that David was trying to be funny and, maybe, a little bit flirty), the general consensus, at first blush, was that it wasn't a big deal. It was only after the issue was rehashed several times in the confessional that each person seemed to realize it as a moment of great import. One could almost see each cast member realizing that this made great drama as the issue built and built. In the end, the producers cited Tami's request for safety and removed David.

Secondly, it's no coincidence that the two characters at the heart of the major strife in seasons one and two were both black men. The Real World aimed to be a microcosm of American society, and at least in this respect, it succeeded. Black men would find themselves vilified and ostracized for much of the show's run.