Mentioned in:

Most Anticipated: The Great Winter 2025 Preview

It's cold, it's grey, its bleak—but winter, at the very least, brings with it a glut of anticipation-inducing books. Here you’ll find nearly 100 titles that we’re excited to cozy up with this season. Some we’ve already read in galley form; others we’re simply eager to devour based on their authors, subjects, or blurbs. We'd love for you to find your next great read among them.

The Millions will be taking a hiatus for the next few months, but we hope to see you soon.

—Sophia Stewart, editor

January

The Legend of Kumai by Shirato Sanpei, tr. Richard Rubinger (Drawn & Quarterly)

The epic 10-volume series, a touchstone of longform storytelling in manga now published in English for the first time, follows outsider Kamui in 17th-century Japan as he fights his way up from peasantry to the prized role of ninja. —Michael J. Seidlinger

The Life of Herod the Great by Zora Neale Hurston (Amistad)

In the years before her death in 1960, Hurston was at work on what she envisioned as a continuation of her 1939 novel, Moses, Man of the Mountain. Incomplete, nearly lost to fire, and now published for the first time alongside scholarship from editor Deborah G. Plant, Hurston’s final manuscript reimagines Herod, villain of the New Testament Gospel accounts, as a magnanimous and beloved leader of First Century Judea. —Jonathan Frey

Mood Machine by Liz Pelly (Atria)

When you eagerly posted your Spotify Wrapped last year, did you notice how much of what you listened to tended to sound... the same? Have you seen all those links to Bandcamp pages your musician friends keep desperately posting in the hopes that maybe, just maybe, you might give them money for their art? If so, this book is for you. —John H. Maher

My Country, Africa by Andrée Blouin (Verso)

African revolutionary Blouin recounts a radical life steeped in activism in this vital autobiography, from her beginnings in a colonial orphanage to her essential role in the continent's midcentury struggles for decolonization. —Sophia M. Stewart

The First and Last King of Haiti by Marlene L. Daut (Knopf)

Donald Trump repeatedly directs extraordinary animus towards Haiti and Haitians. This biography of Henry Christophe—the man who played a pivotal role in the Haitian Revolution—might help Americans understand why. —Claire Kirch

The Bewitched Bourgeois by Dino Buzzati, tr. Lawrence Venuti (NYRB)

This is the second story collection, and fifth book, by the absurdist-leaning midcentury Italian writer—whose primary preoccupation was war novels that blend the brutal with the fantastical—to get the NYRB treatment. May it not be the last. —JHM

Y2K by Colette Shade (Dey Street)

The recent Y2K revival mostly makes me feel old, but Shade's essay collection deftly illuminates how we got here, connecting the era's social and political upheavals to today. —SMS

Darkmotherland by Samrat Upadhyay (Penguin)

In a vast dystopian reimagining of Nepal, Upadhyay braids narratives of resistance (political, personal) and identity (individual, societal) against a backdrop of natural disaster and state violence. The first book in nearly a decade from the Whiting Award–winning author of Arresting God in Kathmandu, this is Upadhyay’s most ambitious yet. —JF

Metamorphosis by Ross Jeffery (Truborn)

From the author of I Died Too, But They Haven’t Buried Me Yet, a woman leads a double life as she loses her grip on reality by choice, wearing a mask that reflects her inner demons, as she descends into a hell designed to reveal the innermost depths of her grief-stricken psyche. —MJS

The Containment by Michelle Adams (FSG)

Legal scholar Adams charts the failure of desegregation in the American North through the story of the struggle to integrate suburban schools in Detroit, which remained almost completely segregated nearly two decades after Brown v. Board. —SMS

Death of the Author by Nnedi Okorafor (Morrow)

African Futurist Okorafor’s book-within-a-book offers interchangeable cover images, one for the story of a disabled, Black visionary in a near-present day and the other for the lead character’s speculative posthuman novel, Rusted Robots. Okorafor deftly keeps the alternating chapters and timelines in conversation with one another. —Nathalie op de Beeck

Open Socrates by Agnes Callard (Norton)

Practically everything Agnes Callard says or writes ushers in a capital-D Discourse. (Remember that profile?) If she can do the same with a study of the philosophical world’s original gadfly, culture will be better off for it. —JHM

Aflame by Pico Iyer (Riverhead)

Presumably he finds time to eat and sleep in there somewhere, but it certainly appears as if Iyer does nothing but travel and write. His latest, following 2023’s The Half Known Life, makes a case for the sublimity, and necessity, of silent reflection. —JHM

The In-Between Bookstore by Edward Underhill (Avon)

A local bookstore becomes a literal portal to the past for a trans man who returns to his hometown in search of a fresh start in Underhill's tender debut. —SMS

Good Girl by Aria Aber (Hogarth)

Aber, an accomplished poet, turns to prose with a debut novel set in the electric excess of Berlin’s bohemian nightlife scene, where a young German-born Afghan woman finds herself enthralled by an expat American novelist as her country—and, soon, her community—is enflamed by xenophobia. —JHM

The Orange Eats Creeps by Grace Krilanovich (Two Dollar Radio)

Krilanovich’s 2010 cult classic, about a runaway teen with drug-fueled ESP who searches for her missing sister across surreal highways while being chased by a killer named Dactyl, gets a much-deserved reissue. —MJS

Mona Acts Out by Mischa Berlinski (Liveright)

In the latest novel from the National Book Award finalist, a 50-something actress reevaluates her life and career when #MeToo allegations roil the off-off-Broadway Shakespearean company that has cast her in the role of Cleopatra. —SMS

Something Rotten by Andrew Lipstein (FSG)

A burnt-out couple leave New York City for what they hope will be a blissful summer in Denmark when their vacation derails after a close friend is diagnosed with a rare illness and their marriage is tested by toxic influences. —MJS

The Sun Won't Come Out Tomorrow by Kristen Martin (Bold Type)

Martin's debut is a cultural history of orphanhood in America, from the 1800s to today, interweaving personal narrative and archival research to upend the traditional "orphan narrative," from Oliver Twist to Annie. —SMS

We Do Not Part by Han Kang, tr. E. Yaewon and Paige Aniyah Morris (Hogarth)

Kang’s Nobel win last year surprised many, but the consistency of her talent certainly shouldn't now. The latest from the author of The Vegetarian—the haunting tale of a Korean woman who sets off to save her injured friend’s pet at her home in Jeju Island during a deadly snowstorm—will likely once again confront the horrors of history with clear eyes and clarion prose. —JHM

We Are Dreams in the Eternal Machine by Deni Ellis Béchard (Milkweed)

As the conversation around emerging technology skews increasingly to apocalyptic and utopian extremes, Béchard’s latest novel adopts the heterodox-to-everyone approach of embracing complexity. Here, a cadre of characters is isolated by a rogue but benevolent AI into controlled environments engineered to achieve their individual flourishing. The AI may have taken over, but it only wants to best for us. —JF

The Harder I Fight the More I Love You by Neko Case (Grand Central)

Singer-songwriter Case, a country- and folk-inflected indie rocker and sometime vocalist for the New Pornographers, takes her memoir’s title from her 2013 solo album. Followers of PNW music scene chronicles like Kathleen Hanna’s Rebel Girl and drummer Steve Moriarty’s Mia Zapata and the Gits will consider Case’s backstory a must-read. —NodB

The Loves of My Life by Edmund White (Bloomsbury)

The 85-year-old White recounts six decades of love and sex in this candid and erotic memoir, crafting a landmark work of queer history in the process. Seminal indeed. —SMS

Blob by Maggie Su (Harper)

In Su’s hilarious debut, Vi Liu is a college dropout working a job she hates, nothing really working out in her life, when she stumbles across a sentient blob that she begins to transform as her ideal, perfect man that just might resemble actor Ryan Gosling. —MJS

Sinkhole and Other Inexplicable Voids by Leyna Krow (Penguin)

Krow’s debut novel, Fire Season, traced the combustible destinies of three Northwest tricksters in the aftermath of an 1889 wildfire. In her second collection of short fiction, Krow amplifies surreal elements as she tells stories of ordinary lives. Her characters grapple with deadly viruses, climate change, and disasters of the Anthropocene’s wilderness. —NodB

Black in Blues by Imani Perry (Ecco)

The National Book Award winner—and one of today's most important thinkers—returns with a masterful meditation on the color blue and its role in Black history and culture. —SMS

Too Soon by Betty Shamieh (Avid)

The timely debut novel by Shamieh, a playwright, follows three generations of Palestinian American women as they navigate war, migration, motherhood, and creative ambition. —SMS

How to Talk About Love by Plato, tr. Armand D'Angour (Princeton UP)

With modern romance on its last legs, D'Angour revisits Plato's Symposium, mining the philosopher's masterwork for timeless, indispensable insights into love, sex, and attraction. —SMS

At Dark, I Become Loathsome by Eric LaRocca (Blackstone)

After Ashley Lutin’s wife dies, he takes the grieving process in a peculiar way, posting online, “If you're reading this, you've likely thought that the world would be a better place without you,” and proceeds to offer a strange ritual for those that respond to the line, equally grieving and lost, in need of transcendence. —MJS

February

No One Knows by Osamu Dazai, tr. Ralph McCarthy (New Directions)

A selection of stories translated in English for the first time, from across Dazai’s career, demonstrates his penchant for exploring conformity and society’s often impossible expectations of its members. —MJS

Mutual Interest by Olivia Wolfgang-Smith (Bloomsbury)

This queer love story set in post–Gilded Age New York, from the author of Glassworks (and one of my favorite Millions essays to date), explores on sex, power, and capitalism through the lives of three queer misfits. —SMS

Pure, Innocent Fun by Ira Madison III (Random House)

This podcaster and pop culture critic spoke to indie booksellers at a fall trade show I attended, regaling us with key cultural moments in the 1990s that shaped his youth in Milwaukee and being Black and gay. If the book is as clever and witty as Madison is, it's going to be a winner. —CK

Gliff by Ali Smith (Pantheon)

The Scottish author has been on the scene since 1997 but is best known today for a seasonal quartet from the late twenty-teens that began in 2016 with Autumn and ended in 2020 with Summer. Here, she takes the genre turn, setting two children and a horse loose in an authoritarian near future. —JHM

Land of Mirrors by Maria Medem, tr. Aleshia Jensen and Daniela Ortiz (D&Q)

This hypnotic graphic novel from one of Spain's most celebrated illustrators follows Antonia, the sole inhabitant of a deserted town, on a color-drenched quest to preserve the dying flower that gives her purpose. —SMS

Bibliophobia by Sarah Chihaya (Random House)

As odes to the "lifesaving power of books" proliferate amid growing literary censorship, Chihaya—a brilliant critic and writer—complicates this platitude in her revelatory memoir about living through books and the power of reading to, in the words of blurber Namwali Serpell, "wreck and redeem our lives." —SMS

Reading the Waves by Lidia Yuknavitch (Riverhead)

Yuknavitch continues the personal story she began in her 2011 memoir, The Chronology of Water. More than a decade after that book, and nearly undone by a history of trauma and the death of her daughter, Yuknavitch revisits the solace she finds in swimming (she was once an Olympic hopeful) and in her literary community. —NodB

The Dissenters by Youssef Rakha (Graywolf)

A son reevaluates the life of his Egyptian mother after her death in Rakha's novel. Recounting her sprawling life story—from her youth in 1960s Cairo to her experience of the 2011 Tahrir Square protests—a vivid portrait of faith, feminism, and contemporary Egypt emerges. —SMS

Tetra Nova by Sophia Terazawa (Deep Vellum)

Deep Vellum has a particularly keen eye for fiction in translation that borders on the unclassifiable. This debut from a poet the press has published twice, billed as the story of “an obscure Roman goddess who re-imagines herself as an assassin coming to terms with an emerging performance artist identity in the late-20th century,” seems right up that alley. —JHM

David Lynch's American Dreamscape by Mike Miley (Bloomsbury)

Miley puts David Lynch's films in conversation with literature and music, forging thrilling and unexpected connections—between Eraserhead and "The Yellow Wallpaper," Inland Empire and "mixtape aesthetics," Lynch and the work of Cormac McCarthy. Lynch devotees should run, not walk. —SMS

There's No Turning Back by Alba de Céspedes, tr. Ann Goldstein (Washington Square)

Goldstein is an indomitable translator. Without her, how would you read Ferrante? Here, she takes her pen to a work by the great Cuban-Italian writer de Céspedes, banned in the fascist Italy of the 1930s, that follows a group of female literature students living together in a Roman boarding house. —JHM

Beta Vulgaris by Margie Sarsfield (Norton)

Named for the humble beet plant and meaning, in a rough translation from the Latin, "vulgar second," Sarsfield’s surreal debut finds a seasonal harvest worker watching her boyfriend and other colleagues vanish amid “the menacing but enticing siren song of the beets.” —JHM

People From Oetimu by Felix Nesi, tr. Lara Norgaard (Archipelago)

The center of Nesi’s wide-ranging debut novel is a police station on the border between East and West Timor, where a group of men have gathered to watch the final of the 1998 World Cup while a political insurgency stirs without. Nesi, in English translation here for the first time, circles this moment broadly, reaching back to the various colonialist projects that have shaped Timor and the lives of his characters. —JF

Brother Brontë by Fernando A. Flores (MCD)

This surreal tale, set in a 2038 dystopian Texas is a celebration of resistance to authoritarianism, a mash-up of Olivia Butler, Ray Bradbury, and John Steinbeck. —CK

Alligator Tears by Edgar Gomez (Crown)

The High-Risk Homosexual author returns with a comic memoir-in-essays about fighting for survival in the Sunshine State, exploring his struggle with poverty through the lens of his queer, Latinx identity. —SMS

Theory & Practice by Michelle De Kretser (Catapult)

This lightly autofictional novel—De Krester's best yet, and one of my favorite books of this year—centers on a grad student's intellectual awakening, messy romantic entanglements, and fraught relationship with her mother as she minds the gap between studying feminist theory and living a feminist life. —SMS

The Lamb by Lucy Rose (Harper)

Rose’s cautionary and caustic folk tale is about a mother and daughter who live alone in the forest, quiet and tranquil except for the visitors the mother brings home, whom she calls “strays,” wining and dining them until they feast upon the bodies. —MJS

Disposable by Sarah Jones (Avid)

Jones, a senior writer for New York magazine, gives a voice to America's most vulnerable citizens, who were deeply and disproportionately harmed by the pandemic—a catastrophe that exposed the nation's disregard, if not outright contempt, for its underclass. —SMS

No Fault by Haley Mlotek (Viking)

Written in the aftermath of the author's divorce from the man she had been with for 12 years, this "Memoir of Romance and Divorce," per its subtitle, is a wise and distinctly modern accounting of the end of a marriage, and what it means on a personal, social, and literary level. —SMS

Enemy Feminisms by Sophie Lewis (Haymarket)

Lewis, one of the most interesting and provocative scholars working today, looks at certain malignant strains of feminism that have done more harm than good in her latest book. In the process, she probes the complexities of gender equality and offers an alternative vision of a feminist future. —SMS

Lion by Sonya Walger (NYRB)

Walger—an successful actor perhaps best known for her turn as Penny Widmore on Lost—debuts with a remarkably deft autobiographical novel (published by NYRB no less!) about her relationship with her complicated, charismatic Argentinian father. —SMS

The Voices of Adriana by Elvira Navarro, tr. Christina MacSweeney (Two Lines)

A Spanish writer and philosophy scholar grieves her mother and cares for her sick father in Navarro's innovative, metafictional novel. —SMS

Autotheories ed. Alex Brostoff and Vilashini Cooppan (MIT)

Theory wonks will love this rigorous and surprisingly playful survey of the genre of autotheory—which straddles autobiography and critical theory—with contributions from Judith Butler, Jamieson Webster, and more.

Fagin the Thief by Allison Epstein (Doubleday)

I enjoy retellings of classic novels by writers who turn the spotlight on interesting minor characters. This is an excursion into the world of Charles Dickens, told from the perspective iconic thief from Oliver Twist. —CK

Crush by Ada Calhoun (Viking)

Calhoun—the masterful memoirist behind the excellent Also A Poet—makes her first foray into fiction with a debut novel about marriage, sex, heartbreak, all-consuming desire. —SMS

Show Don't Tell by Curtis Sittenfeld (Random House)

Sittenfeld's observations in her writing are always clever, and this second collection of short fiction includes a tale about the main character in Prep, who visits her boarding school decades later for an alumni reunion. —CK

Right-Wing Woman by Andrea Dworkin (Picador)

One in a trio of Dworkin titles being reissued by Picador, this 1983 meditation on women and American conservatism strikes a troublingly resonant chord in the shadow of the recent election, which saw 45% of women vote for Trump. —SMS

The Talent by Daniel D'Addario (Scout)

If your favorite season is awards, the debut novel from D'Addario, chief correspondent at Variety, weaves an awards-season yarn centering on five stars competing for the Best Actress statue at the Oscars. If you know who Paloma Diamond is, you'll love this. —SMS

Death Takes Me by Cristina Rivera Garza, tr. Sarah Booker and Robin Myers (Hogarth)

The Pulitzer winner’s latest is about an eponymously named professor who discovers the body of a mutilated man with a bizarre poem left with the body, becoming entwined in the subsequent investigation as more bodies are found. —MJS

The Strange Case of Jane O. by Karen Thompson Walker (Random House)

Jane goes missing after a sudden a debilitating and dreadful wave of symptoms that include hallucinations, amnesia, and premonitions, calling into question the foundations of her life and reality, motherhood and buried trauma. —MJS

Song So Wild and Blue by Paul Lisicky (HarperOne)

If it weren’t Joni Mitchell’s world with all of us just living in it, one might be tempted to say the octagenarian master songstress is having a moment: this memoir of falling for the blue beauty of Mitchell’s work follows two other inventive books about her life and legacy: Ann Powers's Traveling and Henry Alford's I Dream of Joni. —JHM

Mornings Without Mii by Mayumi Inaba, tr. Ginny Tapley (FSG)

A woman writer meditates on solitude, art, and independence alongside her beloved cat in Inaba's modern classic—a book so squarely up my alley I'm somehow embarrassed. —SMS

True Failure by Alex Higley (Coffee House)

When Ben loses his job, he decides to pretend to go to work while instead auditioning for Big Shot, a popular reality TV show that he believes might be a launchpad for his future successes. —MJS

March

Woodworking by Emily St. James (Crooked Reads)

Those of us who have been reading St. James since the A.V. Club days may be surprised to see this marvelous critic's first novel—in this case, about a trans high school teacher befriending one of her students, the only fellow trans woman she’s ever met—but all the more excited for it. —JHM

Optional Practical Training by Shubha Sunder (Graywolf)

Told as a series of conversations, Sunder’s debut novel follows its recently graduated Indian protagonist in 2006 Cambridge, Mass., as she sees out her student visa teaching in a private high school and contriving to find her way between worlds that cannot seem to comprehend her. Quietly subversive, this is an immigration narrative to undermine the various reductionist immigration narratives of our moment. —JF

Love, Queenie by Mayukh Sen (Norton)

Merle Oberon, one of Hollywood's first South Asian movie stars, gets her due in this engrossing biography, which masterfully explores Oberon's painful upbringing, complicated racial identity, and much more. —SMS

The Age of Choice by Sophia Rosenfeld (Princeton UP)

At a time when we are awash with options—indeed, drowning in them—Rosenfeld's analysis of how our modingn idea of "freedom" became bound up in the idea of personal choice feels especially timely, touching on everything from politics to romance. —SMS

Sucker Punch by Scaachi Koul (St. Martin's)

One of the internet's funniest writers follows up One Day We'll All Be Dead and None of This Will Matter with a sharp and candid collection of essays that sees her life go into a tailspin during the pandemic, forcing her to reevaluate her beliefs about love, marriage, and what's really worth fighting for. —SMS

The Mysterious Disappearance of the Marquise of Loria by José Donoso, tr. Megan McDowell (New Directions)

The ever-excellent McDowell translates yet another work by the influential Chilean author for New Directions, proving once again that Donoso had a knack for titles: this one follows up 2024’s behemoth The Obscene Bird of Night. —JHM

Remember This by Anthony Giardina (FSG)

On its face, it’s another book about a writer living in Brooklyn. A layer deeper, it’s a book about fathers and daughters, occupations and vocations, ethos and pathos, failure and success. —JHM

Ultramarine by Mariette Navarro (Deep Vellum)

In this metaphysical and lyrical tale, a captain known for sticking to protocol begins losing control not only of her crew and ship but also her own mind. —MJS

We Tell Ourselves Stories by Alissa Wilkinson (Liveright)

Amid a spate of new books about Joan Didion published since her death in 2021, this entry by Wilkinson (one of my favorite critics working today) stands out for its approach, which centers Hollywood—and its meaning-making apparatus—as an essential key to understanding Didion's life and work. —SMS

Seven Social Movements that Changed America by Linda Gordon (Norton)

This book—by a truly renowned historian—about the power that ordinary citizens can wield when they organize to make their community a better place for all could not come at a better time. —CK

Mothers and Other Fictional Characters by Nicole Graev Lipson (Chronicle Prism)

Lipson reconsiders the narratives of womanhood that constrain our lives and imaginations, mining the canon for alternative visions of desire, motherhood, and more—from Kate Chopin and Gwendolyn Brooks to Philip Roth and Shakespeare—to forge a new story for her life. —SMS

Goddess Complex by Sanjena Sathian (Penguin)

Doppelgängers have been done to death, but Sathian's examination of Millennial womanhood—part biting satire, part twisty thriller—breathes new life into the trope while probing the modern realities of procreation, pregnancy, and parenting. —SMS

Stag Dance by Torrey Peters (Random House)

The author of Detransition, Baby offers four tales for the price of one: a novel and three stories that promise to put gender in the crosshairs with as sharp a style and swagger as Peters’ beloved latest. The novel even has crossdressing lumberjacks. —JHM

On Breathing by Jamieson Webster (Catapult)

Webster, a practicing psychoanalyst and a brilliant writer to boot, explores that most basic human function—breathing—to address questions of care and interdependence in an age of catastrophe. —SMS

Unusual Fragments: Japanese Stories (Two Lines)

The stories of Unusual Fragments, including work by Yoshida Tomoko, Nobuko Takai, and other seldom translated writers from the same ranks as Abe and Dazai, comb through themes like alienation and loneliness, from a storm chaser entering the eye of a storm to a medical student observing a body as it is contorted into increasingly violent positions. —MJS

The Antidote by Karen Russell (Knopf)

Russell has quipped that this Dust Bowl story of uncanny happenings in Nebraska is the “drylandia” to her 2011 Florida novel, Swamplandia! In this suspenseful account, a woman working as a so-called prairie witch serves as a storage vault for her townspeople’s most troubled memories of migration and Indigenous genocide. With a murderer on the loose, a corrupt sheriff handling the investigation, and a Black New Deal photographer passing through to document Americana, the witch loses her memory and supernatural events parallel the area’s lethal dust storms. —NodB

On the Clock by Claire Baglin, tr. Jordan Stump (New Directions)

Baglin's bildungsroman, translated from the French, probes the indignities of poverty and service work from the vantage point of its 20-year-old narrator, who works at a fast-food joint and recalls memories of her working-class upbringing. —SMS

Motherdom by Alex Bollen (Verso)

Parenting is difficult enough without dealing with myths of what it means to be a good mother. I who often felt like a failure as a mother appreciate Bollen's focus on a more realistic approach to parenting. —CK

The Magic Books by Anne Lawrence-Mathers (Yale UP)

For that friend who wants to concoct the alchemical elixir of life, or the person who cannot quit Susanna Clark’s Jonathan Strange and Mr. Norrell, Lawrence-Mathers collects 20 illuminated medieval manuscripts devoted to magical enterprise. Her compendium includes European volumes on astronomy, magical training, and the imagined intersection between science and the supernatural. —NodB

Theft by Abdulrazak Gurnah (Riverhead)

The first novel by the Tanzanian-British Nobel laureate since his surprise win in 2021 is a story of class, seismic cultural change, and three young people in a small Tanzania town, caught up in both as their lives dramatically intertwine. —JHM

Twelve Stories by American Women, ed. Arielle Zibrak (Penguin Classics)

Zibrak, author of a delicious volume on guilty pleasures (and a great essay here at The Millions), curates a dozen short stories by women writers who have long been left out of American literary canon—most of them women of color—from Frances Ellen Watkins Harper to Zitkala-Ša. —SMS

I'll Love You Forever by Giaae Kwon (Holt)

K-pop’s sky-high place in the fandom landscape made a serious critical assessment inevitable. This one blends cultural criticism with memoir, using major artists and their careers as a lens through which to view the contemporary Korean sociocultural landscape writ large. —JHM

The Buffalo Hunter Hunter by Stephen Graham Jones (Saga)

Jones, the acclaimed author of The Only Good Indians and the Indian Lake Trilogy, offers a unique tale of historical horror, a revenge tale about a vampire descending upon the Blackfeet reservation and the manifold of carnage in their midst. —MJS

True Mistakes by Lena Moses-Schmitt (University of Arkansas Press)

Full disclosure: Lena is my friend. But part of why I wanted to be her friend in the first place is because she is a brilliant poet. Selected by Patricia Smith as a finalist for the Miller Williams Poetry Prize, and blurbed by the great Heather Christle and Elisa Gabbert, this debut collection seeks to turn "mistakes" into sites of possibility. —SMS

Perfection by Vicenzo Latronico, tr. Sophie Hughes (NYRB)

Anna and Tom are expats living in Berlin enjoying their freedom as digital nomads, cultivating their passion for capturing perfect images, but after both friends and time itself moves on, their own pocket of creative freedom turns boredom, their life trajectories cast in doubt. —MJS

Guatemalan Rhapsody by Jared Lemus (Ecco)

Jemus's debut story collection paint a composite portrait of the people who call Guatemala home—and those who have left it behind—with a cast of characters that includes a medicine man, a custodian at an underfunded college, wannabe tattoo artists, four orphaned brothers, and many more.

Pacific Circuit by Alexis Madrigal (MCD)

The Oakland, Calif.–based contributing writer for the Atlantic digs deep into the recent history of a city long under-appreciated and under-served that has undergone head-turning changes throughout the rise of Silicon Valley. —JHM

Barbara by Joni Murphy (Astra)

Described as "Oppenheimer by way of Lucia Berlin," Murphy's character study follows the titular starlet as she navigates the twinned convulsions of Hollywood and history in the Atomic Age.

Sister Sinner by Claire Hoffman (FSG)

This biography of the fascinating Aimee Semple McPherson, America's most famous evangelist, takes religion, fame, and power as its subjects alongside McPherson, whose life was suffused with mystery and scandal. —SMS

Trauma Plot by Jamie Hood (Pantheon)

In this bold and layered memoir, Hood confronts three decades of sexual violence and searches for truth among the wreckage. Kate Zambreno calls Trauma Plot the work of "an American Annie Ernaux." —SMS

Hey You Assholes by Kyle Seibel (Clash)

Seibel’s debut story collection ranges widely from the down-and-out to the downright bizarre as he examines with heart and empathy the strife and struggle of his characters. —MJS

James Baldwin by Magdalena J. Zaborowska (Yale UP)

Zaborowska examines Baldwin's unpublished papers and his material legacy (e.g. his home in France) to probe about the great writer's life and work, as well as the emergence of the "Black queer humanism" that Baldwin espoused. —CK

Stop Me If You've Heard This One by Kristen Arnett (Riverhead)

Arnett is always brilliant and this novel about the relationship between Cherry, a professional clown, and her magician mentor, "Margot the Magnificent," provides a fascinating glimpse of the unconventional lives of performance artists. —CK

Paradise Logic by Sophie Kemp (S&S)

The deal announcement describes the ever-punchy writer’s debut novel with an infinitely appealing appellation: “debauched picaresque.” If that’s not enough to draw you in, the truly unhinged cover should be. —JHM

[millions_email]

A Year in Reading: 2024

Welcome to the 20th (!) installment of The Millions' annual Year in Reading series, which gathers together some of today's most exciting writers and thinkers to share the books that shaped their year. YIR is not a collection of yearend best-of lists; think of it, perhaps, as an assemblage of annotated bibliographies. We've invited contributors to reflect on the books they read this year—an intentionally vague prompt—and encouraged them to approach the assignment however they choose.

In writing about our reading lives, as YIR contributors are asked to do, we inevitably write about our personal lives, our inner lives. This year, a number of contributors read their way through profound grief and serious illness, through new parenthood and cross-country moves. Some found escape in frothy romances, mooring in works of theology, comfort in ancient epic poetry. More than one turned to the wisdom of Ursula K. Le Guin. Many describe a book finding them just when they needed it.

Interpretations of the assignment were wonderfully varied. One contributor, a music critic, considered the musical analogs to the books she read, while another mapped her reads from this year onto constellations. Most people's reading was guided purely by pleasure, or else a desire to better understand events unfolding in their lives or larger the world. Yet others centered their reading around a certain sense of duty: this year one contributor committed to finishing the six Philip Roth novels he had yet to read, an undertaking that he likens to “eating a six-pack of paper towels.” (Lucky for us, he included in his essay his final ranking of Roth's oeuvre.)

The books that populate these essays range widely, though the most commonly noted title this year was Tony Tulathimutte’s story collection Rejection. The work of newly minted National Book Award winner Percival Everett, particularly his acclaimed novel James, was also widely read and written about. And as the genocide of Palestinians in Gaza enters its second year, many contributors sought out Isabella Hammad’s searing, clear-eyed essay Recognizing the Stranger.

Like so many endeavors in our chronically under-resourced literary community, Year in Reading is a labor of love. The Millions is a one-person editorial operation (with an invaluable assist from SEO maven Dani Fishman), and producing YIR—and witnessing the joy it brings contributors and readers alike—has been the highlight of my tenure as editor. I’m profoundly grateful for the generosity of this year’s contributors, whose names and entries will be revealed below over the next three weeks, concluding on Wednesday, December 18. Be sure to subscribe to The Millions’ free newsletter to get the week’s entries sent straight to your inbox each Friday.

—Sophia Stewart, editor

Becca Rothfeld, author of All Things Are Too Small

Carvell Wallace, author of Another Word for Love

Charlotte Shane, author of An Honest Woman

Brianna Di Monda, writer and editor

Nell Irvin Painter, author of I Just Keep Talking

Carrie Courogen, author of Miss May Does Not Exist

Ayşegül Savaş, author of The Anthropologists

Zachary Issenberg, writer

Tony Tulathimutte, author of Rejection

Ann Powers, author of Traveling: On the Path of Joni Mitchell

Lidia Yuknavitch, author of Reading the Waves

Nicholas Russell, writer and critic

Daniel Saldaña París, author of Planes Flying Over a Monster

Lili Anolik, author of Didion and Babitz

Deborah Ghim, editor

Emily Witt, author of Health and Safety

Nathan Thrall, author of A Day in the Life of Abed Salama

Lena Moses-Schmitt, author of True Mistakes

Jeremy Gordon, author of See Friendship

John Lee Clark, author of Touch the Future

Ellen Wayland-Smith, author of The Science of Last Things

Edwin Frank, publisher and author of Stranger Than Fiction

Sophia Stewart, editor of The Millions

A Year in Reading Archives: 2023, 2022, 2021, 2020, 2019, 2018, 2017, 2016, 2015, 2014, 2013, 2011, 2010, 2009, 2008, 2007, 2006, 2005

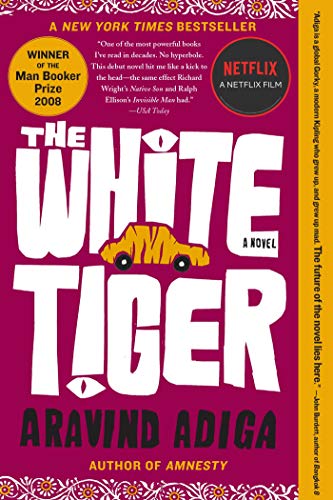

Tuesday New Release Day: Starring Burns, Adiga, Taylor, Phillips, Vollmann, and More

Here’s a quick look at some notable books—new titles from the likes of Anna Burns, Aravind Adiga, Brandon Taylor, Rowan Ricardo Phillips, William T. Vollmann, and more—that are publishing this week.

Want to learn more about upcoming titles? Then go read our most recent book preview. Want to help The Millions keep churning out great books coverage? Then sign up to be a member today.

Little Constructions by Anna Burns

Here's what Publishers Weekly had to say about Little Constructions: "Belfast native Burns’s raucous, exacting modernist crime novel (after the Booker Prize–winning Milkman) skewers men’s incomprehension of women. After a young woman named Jetty Doe confounds a gun shop owner in a town known as Tiptoe Floorboard by snatching a Kalashnikov rifle and throwing a pile of money at him in pursuit of a crime of passion, shop owner Tom Spaders, already traumatized from being stabbed by teenagers in a mugging the year before, copes with the shock by blubbering to a friend about the woman’s apparent ignorance over the type of gun she’d wanted. The story then zigs and zags through a wild chronicle of the Doe crime syndicate and its core members’ immediate family, whose similar-sounding names—Jotty, John, Johnjoe, Janet, Janine, etc.—belie their complex, distinct identities (on Julie Doe: 'This fifteen-year-old was older than her mother’s thirtysomething friend'). Burns’s narrator is a garrulous raconteur who drops in damning characterizations of men ('Why couldn’t she be quiet and just listen and remain quiet even after she’d listened?,' one wonders about his wife) while unspooling the freewheeling account of the Doe family’s occult superstitions, their quirky sensitivity to noises, and the bloody brouhaha that follows the arrest of several gang members. While the narrator’s digressive woolgathering will test some readers’ patience, the acerbic gender commentary tightens the slack. Burns’s fans will find much to chew on."

Amnesty by Aravind Adiga

Here's what Publishers Weekly had to say about Amnesty: "Adiga (The White Tiger) briskly captures an undocumented immigrant’s moral dilemma over whether to help the police solve a murder or remain under the radar in this engrossing tale. After leaving Sri Lanka to attend college in Sydney, Dhananjaya 'Danny' Rajaratnam quits school, loses his student visa, and fails to gain refugee status, but he stays in Australia out of fear for his safety back home, where he was misidentified as a Tamil terrorist. He sleeps in a grocery storeroom and earns cash cleaning homes and doing odd jobs. For four years he escapes notice by authorities; even his leftist Vietnamese girlfriend, Sonja, doesn’t know he’s in the country illegally. After one of his clients—Indian-born Radha Thomas—is murdered, Danny deduces that her murderer is her lover, a violent man nicknamed the Doctor. Danny knows Radha and the Doctor frequented the creek where Radha’s body was discovered, and that the Doctor owned a jacket resembling the one wrapped around the body. Adiga recounts Danny’s thoughts, memories, doubts, and hesitation as well as his aborted phone calls with police and ominous contacts with the Doctor, all within a single day. With nuance and vivid faced by a range of Asian Australians while highlighting the dangers faced by the Tamils of Sri Lanka. Adiga’s enthralling depiction of one immigrant’s tough situation humanizes a complex and controversial global dilemma."

Real Life by Brandon Taylor

Here's what Publishers Weekly had to say about Real Life: "Taylor’s intense, introspective debut tackles the complicated desires of a painfully introverted gay black graduate student over the course of a tumultuous weekend. Wallace, a biochemistry student from Alabama at an unnamed contemporary Midwestern university, discovers his experiment involving breeding nematodes ruined by contaminating mold. Though distraught and facing tedious work, he reluctantly meets up with friends from his program to celebrate the last weekend of summer. He discloses to them the recent death of his estranged father, who did not protect him from sexual abuse by a family friend as a child. Wallace is perpetually ill at ease with his white friends and labmates, especially surly Miller, who unexpectedly admits a sexual interest in Wallace. Over the following two days, Wallace and Miller awkwardly begin a secret, volatile sexual relationship with troubling violence between them at its margins. As Wallace begins to doubt his future as an academic and continues to have fraught social interactions, he reveals more about his heartbreaking past to Miller, building toward an unsettling, unresolved conclusion between the two men. Wallace’s inconsistent emotional states when he’s in Miller’s company can be jarring; the novel is at its best and most powerful when Wallace is alone and readers witness his interior solitude in the face of the racism and loneliness he endures. Taylor’s perceptive, challenging exploration of the many kinds of emotional costs will resonate with readers looking for complex characters and rich prose."

Living Weapon by Rowan Ricardo Phillips

Here's what Publishers Weekly had to say about Living Weapon: "In his dazzling third collection, Phillips (Heaven) explores social ills while celebrating poetry’s ability to provide solace and sense during times of upheaval. Two prose poems anchor the book: the first, the standout of the collection, is '1776,' in which Phillips imagines himself as a winged angel standing atop the Freedom Tower in New York City, observing the city below: 'Lit streets run from it, electric arteries and veins. Manhattan’s never seemed so empty, so narrow, a pupil of a cat’s eye.' Phillips imbues the book with the divisiveness and violence of the present moment: 'We are all in prison./ This is the brutal lesson of the slouching century,// Swilled like a sour stone/ Through the vein of the beast.' In 'Mortality Ode,' he narrates a scene in which several police officers enter a cellphone store and browse casually. Nothing dramatic occurs, but the simple presence of the officers conveys a tension born from the speaker’s subtle understanding that the police are a threat to his safety. In 'Thoughts and Prayers,' Phillips addresses the subject of gun violence directly, declaring that the refusal to take action to stop the epidemic is the real evil: 'the end of endings; the death/ Of change.' Phillips’s latest is lyrical, imaginative, and steeped in a keen understanding of current events."

Home Making by Lee Matalone

Here's what Publishers Weekly had to say about Home Making: "Rumpus columnist Matalone’s heady, lyrical debut overlays an adopted woman’s journey into motherhood with her daughter’s story of making a home for herself as an adult. Born in Tokyo to a Japanese mother and French father, Cybil is adopted by an American couple in Arizona in the 1950s and eventually has a daughter, Chloe, who, in the present, struggles to make a home out of a sprawling house she buys in Virginia while estranged from her husband, Pat, contrasting their old house with Le Corbusier’s aphorism, 'A house is a machine for living in' ('machines break, become defunct'). In spare chapters, Mantalone moves back and forth in time to trace the shapes of Cybil’s and Chloe’s identities through their relationships to domestic spaces. As Chloe wanders from dining room to kitchen to closet in her new house, she ruminates on the varied meanings of home, reflecting on her childhood and contemplating a future with her best friend, Beau, a gay man who glibly encourages her, 'As the great sculpture of pirouetting steel, Richard Serra, said, space is material.' In measured prose, Matalone draws out connections between past and present to illuminate the mother and daughter’s shared sense of ambiguity toward motherhood. Matalone’s cool reflections on art and architecture will appeal to fans of Chris Kraus."

The Lucky Star by William T. Vollmann

Here's what Publishers Weekly had to say about The Lucky Star: "Vollmann’s sprawling and provocatively playful novel revisits the sordid setting of his early collection The Rainbow Stories, where sexual desire shapes characters’ self-expression and pursuit of love, power, and human connection. A circle of friends is bonded by their relationship to a character named Neva, often referred to as 'the lesbian.' They meet at a San Francisco spot called the Y Bar in 2015, where they find support in their collective company and become a de facto family. Among them are the matriarch, a bartender named Francine; Shantelle, a transgender prostitute; the largely unnoticed hard-drinking barfly Richard, who provides florid narration; and the starry-eyed Frank, who has renamed himself after his icon, Judy Garland. Vollmann elaborately researched the tumultuous life of the real Garland, lending passion and credence to Richard’s extensive knowledge of the late singer. As Neva evolves from an innocent to an icon on par with Marlene Dietrich, at least in the eyes of the Y Bar circle, she guides and mentors their sexual self-discovery, helping define their boundaries and gain confidence. The Y Bar crowd’s otherwise static plotlines are tightened by the interweaving of their common experiences. Vollmann’s challenging novel is full of memorable moments."

Also on shelves: Where You’re All Going by Joan Frank.

The Stories That Change Us Forever: The Millions Interviews Julie Buntin

For readers who haven’t already discovered Julie Buntin’s Marlena, this visceral, gripping novel combines humanity with a thrilling edge. We watch as Marlena descends into addiction, but rather than being allowed to simply be voyeurs, we’re forced to face our own complicity in the vulnerability of girls—all girls, not just the reckless ones.

I was lucky enough to catch Julie during her paperback tour, and over a few weeks of emailing, we had the following conversation.

The Millions: One of the (many) gorgeously vivid, telling images of the book, for me, came near the end, when the narrator, Cat, goes back to one of the places she frequented as a teen and finds this: “A poster on the leftmost wall of a girl bent over, holding her ass apart, her face hanging down between her ankles, a cigarette burn in the middle of each cheek.”

As a psychiatrist, one aspect of the book I really appreciated and want to make sure gets the recognition it deserves is how skillfully and artfully you weave together the twin themes of trauma and addiction. It's estimated that nearly 80 percent of people with PTSD, either from “civilian” causes (such as childhood sexual abuse and rape) or “military” (from combat exposure), suffer from some form of addiction, the most common of which is nicotine dependence and heavy smoking, with up to half of PTSD patients in some cohorts reporting some degree of opioid abuse (most commonly prescription). We know also that the endogenous opioid system (endorphin, dynorphin) is engaged during the formation of traumatic memories. So at this point in the history of neuroscience, we actually know a lot about the science that links trauma with addiction [for readers particularly interested in this, I recommend Neurobiology of Addiction, by George Koob, a genius scientist at the NIH].

Yet one of the strengths of your novel is how all that history, all the science and statistics, are so effectively submerged and seen through an adolescent perspective that absolutely knows “something is wrong” but not exactly what. In that way the book reminded me of Emma Donoghue’s Room, where the 5-year-old boy's view makes clear how disturbed the situation is without ever getting “clinical” and removing the reader from the visceral experiences that he's going through.

That poster—the brutally degraded young woman, senselessly violated with those painful cigarette burns but posing for a picture, allowing herself to be consumed—that in one image tells so much about the story of trauma and addiction and how they're linked, how Marlena's most self-abasing moments reflect such a complex mix of the symptoms of PTSD (self-blame, cognitive distortions, risk-taking/recklessness, suicidality, hopelessness, hypervigilance) and her ongoing craving to use.

What did you already know about addiction and trauma before writing the book, and what do you feel like you learned, and how did you learn it? Are there experiences from writing the book that you feel could be useful for emerging writers? What do you think are some of the key differences between writing about addiction in the memoir vs. novel mode? Did you intend, as I felt, that Marlena has so much more self-knowledge than she is sharing with the (younger) narrator Cat—and yet there's something really avoidant in this "best friendship" for Marlena?

Julie Buntin: Most of what I knew about addiction and trauma prior to writing the book came from lived experience—by which I mean not necessarily experiences I’d had firsthand, but ones I’d witnessed. I have a family member, a young woman, who struggles with addiction, and her relationship to drugs and alcohol does seem intertwined with the fact that, even though she is blessed in many ways, her life has also had an outsize number of losses, including a central one that seems to have infected her worldview in a destructive way.

As I wrote the book, focusing in on Marlena’s character, I was always asking myself what felt true. I’m not sure if this will be useful to emerging writers, but it was useful to me; what feels true for your character isn’t always going to be the thing you want to write. Especially when Cat and Marlena start drifting apart near the end—I knew that was the authentic thing, considering the seriousness of Marlena’s addiction, but I hated writing it. And thank you for your observation that the friendship is avoidant for Marlena—I think that is absolutely right. She gets so close to Cat in part because Cat isn’t going to call her out, isn’t going to challenge her outright, and Cat’s someone she can fool into thinking she’s OK. But then, when Cat starts to figure it out, Marlena retreats inward.

[millions_ad]

TM: Did you, as you were writing the novel, think about "heroin chic" and any problems of glamorizing addiction and its aftermath? The one consequence presented as a discrete event is Marlena's (sudden) death—but even that has so much brilliant shadowing around it (in particular the brief scene where Cat sees her looking like a scarecrow, a "meth-head," skeletal and even her beautiful hair ugly). Other consequences seem more pervasive, subtle, expressed through mood shifts in the narrator, like the wistfulness you conveyed so beautifully as Cat compares what she's doing in Silver Lake with what her school friend Haesung would've done, or the letter Cat writes to her absent father. There's no question that we feel the negatives of addiction. And yet these kinds of sentences convey the thrill as well: “It's not a question. I love this wildness. I crave it.”

Did you consciously think about or set up this ambivalence, to have “drug glamour” in there along with devastation?

JB: I thought a lot about the danger of glamorizing addiction while writing this, especially because I hoped that the book might be read by older teenagers. It was constantly on my mind, and while I had no interest in writing a cautionary tale, either, if the balance doesn’t tilt more toward cautionary tale then I’ve failed myself a little bit. I had to walk a careful line in the narrative—I needed to show all the ways this lifestyle could be intoxicating, how it might suck a girl like Cat in, and then slowly reveal the way those choices add up to a trap that nobody is going to want to find themselves in—and furthermore, a trap that extends past the teenage years and into adulthood. One of the ways of doing that, narratively, was to make Cat, herself, an addict.

I’ve often had people tell me very matter-of-factly that Cat drinks because she’s sad/guilty about what happened with Marlena, and while I never argue with that interpretation—certainly the narrative, structured as it is, argues that—I always find it very interesting that no one ever says, oh, of course Cat’s an alcoholic, because she started binge drinking frequently at 15 years old and her brain chemistry changed forever. I wanted both of those things to be at work at once, and for Cat’s trajectory, which on the surface seems great—upwardly mobile, at the very least—to be itself a warning about the danger of experimentation that goes too far. It’s not just your life that’s at stake, in terms of an early death, as in Marlena’s case; it’s also the possibility of living a life that’s not reliant upon a substance, that’s not in some way dimmed and hemmed in by dependency.

TM: So one of the other major symptoms of PTSD is "numbing" or "numbness." Current science actually identifies a subgroup of PTSD patients who mainly are numbed out, who dissociate from current reality when remembering or reminded of their trauma, rather than showing more of a "fight or flight" response. I felt that the New York sections of the book told from Cat's adult perspective so adeptly expressed what it is like to be numb in this way, and it made me think differently about what Cat and Marlena went through (including with various exploitative adult males). Can you talk about the craft challenges of writing a "numb" narrator? I'm thinking of Bret Easton Ellis's Less than Zero (describing some of those scenes of drug use among a slightly younger cohort of adults in their early vs. late 20s) but also of Zadie Smith in The Autograph Man and even Aravind Adiga's narrator in The White Tiger and Akhil Sharma's narrator in An Obedient Father. All of these have numb narrators facing the aftermath, one could argue, of being complicit in one's own traumatization. Numbness as a form of self-punishment but also involuntary. And numbness seems to become a force for delay, for waiting to move forward, for even blocking oneself from moving forward. A kind of semi-paralyzing spell that can only be broken by the person experiencing it and not externally by a therapist pointing it out.

How can you (how did you?) sustain an energetic and gripping narrative drive while writing a narrator who was experiencing a (very understandable) numbness? Did this challenge relate to what you said you did in 2015 (rewrite the novel substantially after it sold) and, to support other writers out there breathing hard from "editorial letters," can you talk about your revision process and what that was like?

JB: Oh, I love this question, and I love that you used the word numb. Also, I wasn’t aware of that background on PTSD, though it relates so deeply to how I thought of Cat’s character. Certainly the experience of befriending Marlena, all of her experiences in Silver Lake, and then the sudden loss of Marlena all formed this hinge point in her life: She was one way before, and she would never be the same again after. That’s the kind of moment I’m fascinated by as a novelist—this periods when we become ourselves, for better or worse, the stories that change us forever.

When I was writing Cat as an adult, I was actively striving for numbness, which was challenging! You can never sacrifice your reader’s interest to achieve an effect, or I don’t believe you should, anyway, so I had to make those scenes in New York feel sort of muffled while being interesting and moving the story forward, which was genuinely hard. As you mention in your question, I did rewrite the novel after it sold, in an attempt to address some of my editor’s concerns—and as I worked through her comments, I kept coming up against a sort of larger question. We’re often, as writers, told that we need to know the answer to the question, “Why this story?” And I definitely knew why I was writing it—as I’ve discussed a little bit above. So the urgency and intensity were there, but there was something missing structurally. The question wasn’t just why this story, I realized—it was why this story, now? Why is Cat revisiting this at this precise moment in her life? And the answer actually was that numbness. She’s gotten everything—a whole new life, a better life than her mother and Jimmy, and yet why is she numb?

I thought I might be able to make it gripping and interesting by virtue of the contrast between the past sections and the present sections—the tonal dissonance, so to speak, might keep readers moving forward, wanting to know how Cat got to be quite like this. I also worked on varying the language, clipping it a little when Cat’s sober, and making it loose and blurry when she’s not. I also think there’s something inherently interesting, for better or for worse, about reading someone who is on the brink in their own life, and Cat really is, with her drinking. I hoped the reader would care enough about her, even if they didn’t exactly like her, to want to figure out whether she was going to pull through.

Most Anticipated: The Great 2017 Book Preview

Although 2016 has gotten a bad rap, there were, at the very least, a lot of excellent books published. But this year! Books from George Saunders, Roxane Gay, Hari Kunzru, J.M. Coetzee, Rachel Cusk, Jesmyn Ward? A lost manuscript by Claude McKay? A novel by Elif Batuman? Short stories by Penelope Lively? A memoir by Yiyun Li? Books from no fewer than four Millions staffers? It's a feast. We hope the following list of 80-something upcoming books peps you up for the (first half of the) new year. You'll notice that we've re-combined our fiction and nonfiction lists, emphasizing fiction as in the past. And, continuing a tradition we started this fall, we'll be doing mini previews at the beginning of each month -- let us know if there are other things we should be looking forward to. (If you are a big fan of our bi-annual Previews and find yourself referring to them year-round, please consider supporting our efforts by becoming a member!)

January

Difficult Women by Roxane Gay: Gay has had an enormously successful few years. In 2014, her novel, An Untamed State, and an essay collection, Bad Feminist, met with wide acclaim, and in the wake of unrest over anti-black police violence, hers was one of the clearest voices in the national conversation. While much of Gay’s writing since then has dealt in political thought and cultural criticism, she returns in 2017 with this short story collection exploring the various textures of American women’s experience. (Ismail)

Human Acts by Han Kang: Korean novelist Kang says all her books are variations on the theme of human violence. The Vegetarian, her first novel translated into English, arrested readers with the contempt showered upon an “unremarkable” wife who became a vegetarian after waking from a nightmare. Kang’s forthcoming Human Acts focuses on the 1980 Korean Gwangju Uprising, when Gwangju locals took up arms in retaliation for the massacre of university students who were protesting. Within Kang tries to unknot “two unsolvable riddles” -- the intermingling of two innately human yet disparate tendencies, the capacity for cruelty alongside that for selflessness and dignity. (Anne)

Transit by Rachel Cusk: Everyone who read and reveled in the nimble formal daring of Outline is giddy to read Transit, which follows the same protagonist, Faye, as she navigates life after separating from her husband. Both Transit and Outline are made up of stories other people tell Faye, and in her rave in The Guardian, Tessa Hadley remarks that Cusk's structure is "a striking gesture of relinquishment. Faye’s story contends for space against all these others, and the novel’s meaning is devolved out from its centre in her to a succession of characters. It’s a radically different way of imagining a self, too -- Faye’s self." (Edan)

4321 by Paul Auster: Multiple timelines are nothing new at this point, but it’s doubtful they’ve ever been used in quite the way they are in 4321, Auster’s first novel since his 2010 book Sunset Park. In his latest, four timelines branch off the moment the main character is born, introducing four separate Archibald Isaac Fergusons that grow more different as the plot wears on. They’re all, in their own ways, tied up with Amy Schneiderman, who appears throughout the book’s realities. (Thom)

Collected Stories by E.L. Doctorow: Doctorow is known for historical novels like Ragtime and The Book of Daniel, but he also wrote some terrific stories, and shortly before his death in 2015 he selected and revised 15 of his best. Fans who already own his 2011 collection All the Time in the World may want to give this new one a miss, since many of the selections overlap, but readers who only know Doctorow as a novelist may want to check out his classic early story “A Writer in the Family,” as well as others like “The Water Works” and “Liner Notes: The Songs of Billy Bathgate,” which are either precursors of or companion pieces to his novels. (Michael B.)

Enigma Variations by André Aciman: The CUNY Professor New York magazine called “the most exciting new fiction writer of the 21st century” returns with a romantic/erotic bildungsroman following protagonist Paul from Italy to New York, from adolescence to adulthood. Kirkus called it an “eminently adult look at desire and attachment.” (Lydia)

Scratch: Writers, Money, and the Art of Making a Living, edited by Manjula Martin: Martin ran the online magazine Scratch from 2013 to 2015 and in those two years published some terrific and refreshingly transparent interviews with writers about cash money and how it's helped and hindered their lives as artists. The magazine is no longer online, but this anthology includes many of those memorable conversations as well as some new ones. Aside from interviews with the likes of Cheryl Strayed and Jonathan Franzen, the anthology also includes honest and vulnerable essays about making art and making a career --and where those two meet -- from such writers as Meaghan O'Connell and Alexander Chee. It's a useful and inspiring read. (Edan)

Homesick for Another World by Ottessa Moshfegh: A long, dull day of jury duty in 2008 was redeemed by a lunchtime discovery of Unsaid magazine and its lead story “Help Yourself!” by Moshfegh, whose characters were alluring and honest and full of contempt. I made a point to remember her name at the time, but now Moshfegh’s stories appear regularly in The Paris Review and The New Yorker, and her novel Eileen was shortlisted for the 2016 Booker Prize. Her debut collection of stories, Homesick for Another World, gathers many of these earlier stories, and is bound to show why she’s considered one of literature’s most striking new voices. (Anne)

Glaxo by Hernán Ronsino: Ronsino’s English-language debut (translated by Samuel Rutter) is only 100 pages but manages to host four narrators and cover 40 years. Set in a dusty, stagnating town in Argentina, the novel cautiously circles around a decades-old murder, a vanished wife, and past political crimes. Allusions to John Sturges’s Last Train From Gun Hill hint at the vengeance, or justice, to come in this sly Latin American Western. (Matt)

Lucky Boy by Shanthi Sekaran: Set in Berkeley, Sekaran’s novel follows two women: Soli, an undocumented woman from Mexico raising a baby alone while cleaning houses, and an Indian-American woman struggling with infertility who becomes a foster parent to Soli’s son. Kirkus called it “superbly crafted and engrossing.” (Lydia)

A Mother’s Tale by Phillip Lopate: One day in the mid-'80s, Lopate sat down with his tape recorder to capture his mother’s life story, which included, at various times, a stint owning a candy store, a side gig as an actress and singer, and a job on the line at a weapons factory at the height of World War II. Although Lopate didn’t use the tapes for decades, he unearthed them recently and turned them into this book, which consists of a long conversation between himself, his mother, and the person he was in the '80s. (Thom)

The Gringo Champion by Aura Xilonen: Winner of Mexico’s Mauricio Achar Prize for Fiction, Xilonen’s novel (written when she was only 19, and here translated by Andrea Rosenberg) tells the story of a young boy who crosses the Rio Grande. Mixing Spanish and English, El Sur Mexico lauded the novel’s “vulgar idiom brilliantly transformed into art.” (Lydia)

Selection Day by Aravind Adiga: If Selection Day goes on to hit it big, we may remember it as our era’s definitive cricket novel. Adiga -- a Man Booker laureate who won the prize in 2008 for his epic The White Tiger -- follows the lives of Radha and Manju, two brothers whose father raised them to be master batsmen. In the way of The White Tiger, all the characters are deeply affected by changes in Indian society, most of which are transposed into changes in the country’s huge cricket scene. (Thom)

Huck Out West by Robert Coover: Coover, the CAVE-dwelling postmodern luminary, riffs on American’s great humorist in this sequel to Mark Twain’s classic set out West. From the opening pages, in which Tom, over Huck’s objections, sells Jim to slaveholding Cherokees, it is clear that Coover’s picaresque will be a tale of disillusionment. Unlike Tom, “who is always living in a story he’s read in a book so he knows what happens next,” Huck seems wearied and shaken by his continued adventures: “So many awful things had happened since then, so much outright meanness. It was almost like there was something wicked about growing up.” (Matt)

Fever Dream by Samanta Schweblin. Nobel Laureate Mario Vargas Llosa called Schweblin “one of the most promising voices in modern literature in Spanish.” The Argentinian novelist’s fifth book, about “obsession, identity and motherhood,” is her first to be translated into English (by Megan McDowell). It’s been described “deeply unsettling and disorientating” by the publisher and “a wonderful nightmare of a book” by novelist Juan Gabriel Vásquez. (Elizabeth)

Perfect Little World by Kevin Wilson. Wilson’s first novel, The Family Fang, was about the children of performance artists. His second is about a new mother who joins a sort of utopian community called the “Infinite Family Project,” living alongside other couples raising newborns, which goes well until eventually “the gentle equilibrium among the families is upset and it all starts to disintegrate.” He’s been described by novelist Owen King as the “unholy child of George Saunders and Carson McCullers.” (Elizabeth)

Foreign Soil by Maxine Beneba Clarke: Clarke’s award-winning short story collection Foreign Soil is now being published in the U.S. and includes a new story “Aviation,” specifically written for this edition. These character-driven stories take place worldwide -- Australia, Africa, the West Indies, and the U.S. -- and explore loss, inequity, and otherness. Clarke is hailed as an essential writer whose collection challenges and transforms the reader. (Zoë)

American Berserk by Bill Morris: Five years ago, a Millions commenter read Morris’s crackling piece about his experience as a young reporter in Chambersburg, Penn., during the 1970s: “Really, I wish this essay would be a book.” Ask, and you shall receive. To refresh your memories, Morris encountered what one would expect in the pastoral serenity of Pennsylvania Dutch country: “Kidnapping, ostracism, the paranormal, rape, murder, insanity, arson, more murder, attempted suicide -- it added up to a collective nervous breakdown.” Morris has plenty to work with in these lurid tales, but the book is also about the pleasure of profiling those “interesting nobodies” whose stories never make it to the front page, no matter how small the paper. (Matt)

February

Lincoln in the Bardo by George Saunders: For Saunders fans, the prospect of a full-length novel from the short-story master has been something to speculate upon, if not actually expect. Yet Lincoln in the Bardo is a full 368-page blast of Saunders -- dealing in the 1862 death of Abraham Lincoln’s son, the escalating Civil War, and, of course, Buddhist philosophy. Saunders has compared the process of writing longer fiction to “building custom yurts and then somebody commissioned a mansion” -- and Saunders’s first novel is unlikely to resemble any other mansion on the block. (Jacob)

The Schooldays of Jesus by J.M. Coetzee: This sequel to the Nobel Prize-winning South African author’s 2013 novel The Childhood of Jesus picks up shortly after Simón and Inés flee from authorities with their adopted son, David. Childhood was a sometimes thin-feeling allegory of immigration that found Coetzee meditating with some of his perennial concerns -- cultural memory, language, naming, and state violence -- at the expense of his characters. In Schooldays, the allegorical element recedes somewhat into the background as Coetzee tells the story of David’s enrollment in a dance school, his discovery of his passion for dancing, and his disturbing encounters with adult authority. This one was longlisted for the 2016 Man Booker Prize. (Ismail)

To Be a Machine by Mark O’Connell: Millions staffer and author of Millions Original Epic Fail O’Connell brings his superb writing and signature wit and empathy to a nonfiction exploration of the transhumanist movement, complete with cryogenic freezing, robots, and an unlikely presidential bid from the first transhumanist candidate. O’Connell’s sensibility -- his humanity, if you will -- and his subject matter are a match made in heaven. It’s an absolutely wonderful book, but don’t take my non-impartial word for it: Nicholson Baker and Margaret Atwood have plugged it too. (Lydia)

The Refugees by Viet Thanh Nguyen: Pulitzer Prize Winner Nguyen’s short story collection The Refugees has already received starred pre-publication reviews from Kirkus Reviews and Publishers Weekly, among others. Nguyen’s brilliant new work of fiction offers vivid and intimate portrayals of characters and explores identity, war, and loss in stories collected over a period of two decades. (Zoë)

Amiable with Big Teeth by Claude McKay: A significant figure in the Harlem Renaissance, McKay is best-known for his novel Home to Harlem -- which was criticized by W.E.B. Dubois for portraying black people (i.e. Harlem nightlife) as prurient -- “after the dirtier parts of its filth I feel distinctly like taking a bath.” The novel went on to win the prestigious (if short-lived) Harmon Gold Medal and is widely praised for its sensual and brutal accuracy. In 2009, UPenn English professor Jean-Christophe Cloutier discovered the unpublished Amiable with Big Teeth in the papers of notorious, groundbreaking publisher Samuel Roth. A collaboration between Cloutier and Brent Hayes Edwards, a long-awaited, edited, scholarly edition of the novel will be released by Penguin in February. (Sonya)

Dear Friend, from My Life I Write to You in Your Life by Yiyun Li: The Oakland-based Li delivers this memoir of chronic depression and a life lived with books. Weaving sharp literary criticism with a perceptive narrative about her life as an immigrant in America, Your Life isn’t as interested in exploring how literature helps us make sense of ourselves as it is in how literature situates us amongst others. (Ismail)

Autumn by Ali Smith: Her 2015 Baileys prize-winning How to Be Both was an experiment in how a reader experiences time. It has two parts, which can be read in any order. Now, Smith brings us Autumn, the first novel in what will be a Seasonal quartet -- four stand-alone books, each one named after one of the four seasons. Known for writing with experimental elegance, she turns to time in the post Brexit world, specifically Autumn 2016, “exploring what time is, how we experience it, and the recurring markers in the shapes our lives take.” (Claire)

A Separation by Katie Kitamura: A sere and unsettling portrait of a marriage come undone, critics are hailing Kitamura's third book as "mesmerizing" and "magnificent." The narrator, a translator, goes to a remote part of Greece in search of her serially unfaithful husband, only to be further unmoored from any sense that she (and in turn the reader) had of the contours of their shared life. Blurbed by no fewer than six literary heavyweights -- Rivka Galchen, Jenny Offill, Leslie Jamison, Teju Cole, Rachel Kushner, and Karl Ove Knausgaard -- A Separation looks poised to be the literary Gone Girl of 2017. (Kirstin B.)

Things We Lost in the Fire by Mariana Enriquez: This young Argentinian journalist and author has already drawn a lot of attention for her “chilling, compulsive” gothic short stories. One made a December 2016 issue of The New Yorker; many more will be published this spring as Things We Lost in the Fire, which has drawn advanced praise from Helen Oyeyemi and Dave Eggers. The stories themselves follow addicts, muggers, and narcos -- characters Oyeyemi calls “funny, brutal, bruised” -- as they encounter the terrors of everyday life. Fair warning: these stories really will scare you. (Kaulie)

Universal Harvester by John Darnielle. Darnielle is best known for the The Mountain Goats, a band in which he has often been the only member. But his debut novel, Wolf in White Van, was nominated for a number of awards, including the National Book Award for Fiction. His second novel, set in Iowa in the 1990s, is about a video store clerk who discovers disturbing scenes on the store’s tapes. (Elizabeth)

300 Arguments by Sarah Manguso: It's as if, like the late David Markson, Manguso is on a gnomic trajectory toward some single, ultimate truth expressed in the fewest words possible -- or perhaps her poetic impulses have just grown even stronger over time. As its title suggests, this slim volume comprises a sequence of aphorisms ("Bad art is from no one to no one") that in aggregate construct a self-portrait of the memoirist at work. "This book is the good sentences from the novel I didn't write," its narrator writes. (Kirstin B.)

The Woman Next Door by Yewande Omotoso: Set in South Africa, Omotoso’s novel describes the bitter feud between two neighbors, both well-to-do, both widows, both elderly, one black, one white. Described by the TLS as one of the “Best Books by Women Every Man Should Read.” (Lydia)

Running by Cara Hoffman: The third novel from Hoffman, celebrated author of Be Safe I Love You, Running follows a group of three outsiders trying to make it the red light district of Athens in the 1980s. Bridey Sullivan, a wild teenager escaping childhood trauma in the States, falls in with a pair of young “runners” working to lure tourists to cheap Athenian hotels in return for bed and board. The narrative itself flashes between Athens, Sullivan’s youth, and her friend and runner Milo’s life in modern-day New York City. According to Kirkus, this allows the novel to be “crisp and immediate,” “beautiful and atmospheric,” and “original and deeply sad.” (Kaulie)

Lower Ed by Tressie McMillan Cottom: Academic and Twitter eminence McMillan Cottom tackles a subject that, given a recent spate of lawsuits, investigations, and closings, was front-page news for a good part of 2016. Drawing on interviews with students, activists, and executives at for-profit colleges and universities, Lower Ed aims to connect the rise of such institutions with ballooning levels of debt and larger trends of income inequality across the U.S. (Kirstin B.)

Abandon Me by Melissa Febos. Febos’s gifts as a writer seemingly increase with the types of subjects and themes that typically falter in the hands of many memoirists: love (both distant and immediate), family, identity, and addiction. Her adoptive father, a sea captain, looms large in her work: “My captain did not give me religion but other treasures. A bloom of desert roses the size of my arm, a freckled ostrich egg, true pirate stories. My biological father, on the other hand, had given me nothing of use but life...and my native blood.” Febos transports, but her lyricism is always grounded in the now, in the sweet music of loss. (Nick R.)

Pachinko by Min Jin Lee: A sweeping look at four generations of a Korean family who immigrates to Japan after Japan's 1910 annexation of Korea, from the author of Free Food for Millionaires. Junot Díaz says “Pachinko confirms Lee's place among our finest novelists.” (Lydia)

Flâneuse by Lauren Elkin: Following in the literary tradition of Charles Baudelaire, Virginia Woolf and Edgar Allan Poe, Elkin is fascinated by street wanderers and wanderings, but with a twist. The traditional flâneur was always male; Elkin sets out to follow the lives of the subversive flâneuses, those women who have always been “keenly attuned to the creative potential of the city, and the liberating possibilities of a good walk.” In a review in The Guardian, Elkin is imagined as “an intrepid feminist graffiti artist,” writing the names of women across the city she loves; in her book, a combination of “cultural meander” and memoir, she follows the lives of flaneuses as varied as George Sand and Martha Gellhorn in order to consider “what is at stake when a certain kind of light-footed woman encounters the city.” (Kaulie)

March

Exit West by Mohsin Hamid: In an unnamed city, two young people fall in love as a civil war breaks out. As the violence escalates, they begin to hear rumors of a curious new kind of door: at some risk, and for a price, it’s possible to step through a portal into an entirely different place -- Mykonos, for instance, or London. In a recent interview, Hamid said that the portals allowed him “to compress the next century or two of human migration on our planet into the space of a single year, and to explore what might happen after.” (Emily)

The Idiot by Elif Batuman: Between The Possessed -- her 2010 lit-crit/travelogue on a life in Russian letters and her snort-inducing Twitter feed, I am a confirmed Batuman superfan. This March, her debut novel samples Fyodor Dostoevsky in a Bildungsroman featuring the New Jersey-bred daughter of Turkish immigrants who discovers that Harvard is absurd, Europe disturbed, and love positively barking. Yet prose this fluid and humor this endearing are oddly unsettling, because behind the pleasant façade hides a thoughtful examination of the frenzy and confusion of finding your way in the world. (Il’ja R.)

White Tears by Hari Kunzru: A fascinating-sounding novel about musical gentrification, and two white men whose shared obsession with hard-to-find blues recordings leads them to perdition. In a starred review, Publishers Weekly called White Tears "perhaps the ultimate literary treatment of the so-called hipster, tracing the roots of the urban bedroom deejay to the mythic blues troubadours of the antebellum South.” (Lydia)

South and West: From a Notebook by Joan Didion: Excerpts from two of the legendary writer’s commonplace books from the 1970s: one from a road trip through the American south, and one from a Rolling Stone assignment to cover the Patty Hearst trial in California. Perhaps the origin of her observation in Where I Was From: “One difference between the West and the South, I came to realize in 1970, was this: in the South they remained convinced that they had bloodied their land with history. In California we did not believe that history could bloody the land, or even touch it.” (Lydia)