Mentioned in:

A Year in Reading: 2024

Welcome to the 20th (!) installment of The Millions' annual Year in Reading series, which gathers together some of today's most exciting writers and thinkers to share the books that shaped their year. YIR is not a collection of yearend best-of lists; think of it, perhaps, as an assemblage of annotated bibliographies. We've invited contributors to reflect on the books they read this year—an intentionally vague prompt—and encouraged them to approach the assignment however they choose.

In writing about our reading lives, as YIR contributors are asked to do, we inevitably write about our personal lives, our inner lives. This year, a number of contributors read their way through profound grief and serious illness, through new parenthood and cross-country moves. Some found escape in frothy romances, mooring in works of theology, comfort in ancient epic poetry. More than one turned to the wisdom of Ursula K. Le Guin. Many describe a book finding them just when they needed it.

Interpretations of the assignment were wonderfully varied. One contributor, a music critic, considered the musical analogs to the books she read, while another mapped her reads from this year onto constellations. Most people's reading was guided purely by pleasure, or else a desire to better understand events unfolding in their lives or larger the world. Yet others centered their reading around a certain sense of duty: this year one contributor committed to finishing the six Philip Roth novels he had yet to read, an undertaking that he likens to “eating a six-pack of paper towels.” (Lucky for us, he included in his essay his final ranking of Roth's oeuvre.)

The books that populate these essays range widely, though the most commonly noted title this year was Tony Tulathimutte’s story collection Rejection. The work of newly minted National Book Award winner Percival Everett, particularly his acclaimed novel James, was also widely read and written about. And as the genocide of Palestinians in Gaza enters its second year, many contributors sought out Isabella Hammad’s searing, clear-eyed essay Recognizing the Stranger.

Like so many endeavors in our chronically under-resourced literary community, Year in Reading is a labor of love. The Millions is a one-person editorial operation (with an invaluable assist from SEO maven Dani Fishman), and producing YIR—and witnessing the joy it brings contributors and readers alike—has been the highlight of my tenure as editor. I’m profoundly grateful for the generosity of this year’s contributors, whose names and entries will be revealed below over the next three weeks, concluding on Wednesday, December 18. Be sure to subscribe to The Millions’ free newsletter to get the week’s entries sent straight to your inbox each Friday.

—Sophia Stewart, editor

Becca Rothfeld, author of All Things Are Too Small

Carvell Wallace, author of Another Word for Love

Charlotte Shane, author of An Honest Woman

Brianna Di Monda, writer and editor

Nell Irvin Painter, author of I Just Keep Talking

Carrie Courogen, author of Miss May Does Not Exist

Ayşegül Savaş, author of The Anthropologists

Zachary Issenberg, writer

Tony Tulathimutte, author of Rejection

Ann Powers, author of Traveling: On the Path of Joni Mitchell

Lidia Yuknavitch, author of Reading the Waves

Nicholas Russell, writer and critic

Daniel Saldaña París, author of Planes Flying Over a Monster

Lili Anolik, author of Didion and Babitz

Deborah Ghim, editor

Emily Witt, author of Health and Safety

Nathan Thrall, author of A Day in the Life of Abed Salama

Lena Moses-Schmitt, author of True Mistakes

Jeremy Gordon, author of See Friendship

John Lee Clark, author of Touch the Future

Ellen Wayland-Smith, author of The Science of Last Things

Edwin Frank, publisher and author of Stranger Than Fiction

Sophia Stewart, editor of The Millions

A Year in Reading Archives: 2023, 2022, 2021, 2020, 2019, 2018, 2017, 2016, 2015, 2014, 2013, 2011, 2010, 2009, 2008, 2007, 2006, 2005

The Great Fall 2024 Book Preview

With the arrival of autumn comes a deluge of great books. Here you'll find a sampling of new and forthcoming titles that caught our eye here at The Millions, and that we think might catch yours, too. Some we’ve already perused in galley form; others we’re eager to devour based on their authors, plots, or subject matters. We hope your next fall read is among them.

—Sophia Stewart, editor

October

Season of the Swamp by Yuri Herrera, tr. Lisa Dillman [F]

What it is: An epic, speculative account of the 18 months that Benito Juárez spent in New Orleans in 1853-54, years before he became the first and only Indigenous president of Mexico.

Who it's for: Fans of speculative history; readers who appreciate the magic that swirls around any novel set in New Orleans. —Claire Kirch

The Black Utopians by Aaron Robertson [NF]

What it is: An exploration of Black Americans' pursuit and visions of utopia—both ideological and physical—that spans the Reconstruction era to the present day and combines history, memoir, and reportage.

Who it's for: Fans of Saidiya Hartman's Wayward Lives, Beautiful Experiments and Kristen R. Ghodsee's Everyday Utopia. —Sophia M. Stewart

The Third Realm by Karl Ove Knausgaard, tr. Martin Aitken [F]

What it is: The third installment in Knausgaard's Morning Star series, centered on the appearance of a mysterious new star in the skies above Norway.

Who it's for: Real Knausgaard heads only—The Wolves of Eternity and Morning Star are required reading for this one. —SMS

Brown Women Have Everything by Sayantani Dasgupta [NF]

What it is: Essays on the contradictions and complexities of life as an Indian woman in America, probing everything from hair to family to the joys of travel.

Who it's for: Readers of Durga Chew-Bose, Erika L. Sánchez, and Tajja Isen. —SMS

The Plot Against Native America by Bill Vaughn [F]

What it is: The first narrative history of Native American boarding schools— which aimed "civilize" Indigenous children by violently severing them from their culture— and their enduring, horrifying legacy.

Who it's for: Readers of Ned Blackhawk and Kathleen DuVal. —SMS

The Mighty Red by Louise Erdrich [F]

What it is: Erdrich's latest novel set in North Dakota's Red River Valley is a tale of the intertwined lives of ordinary people striving to survive and even thrive in their rural community, despite environmental upheavals, the 2008 financial crisis, and other obstacles.

Who it's for: Readers of cli-fi; fans of Linda LeGarde Grover and William Faulkner. —CK

The Position of Spoons by Deborah Levy [NF]

What it is: The second book from Levy in as many years, diverging from a recent streak of surrealist fiction with a collection of essays marked by exceptional observance and style.

Who it's for: Close lookers and the perennially curious. —John H. Maher

The Bog Wife by Kay Chronister [F]

What it's about: The Haddesley family has lived on the same West Virginia bog for centuries, making a supernatural bargain with the land—a generational blood sacrifice—in order to do so—until an uncovered secret changes everything.

Who it's for: Readers of Karen Russell and Jeff VanderMeer; anyone who has ever used the phrase "girl moss." —SMS

The Great When by Alan Moore [F]

What it's about: When an 18-year old book reseller comes across a copy of a book that shouldn’t exist, it threatens to upend not just an already post-war-torn London, but reality as we know it.

Who it's for: Anyone looking for a Sherlock Holmes-style mystery dipped in thaumaturgical psychedelia. —Daniella Fishman

The Message by Ta-Nehisi Coates [NF]

What it's about: One of our sharpest critical thinkers on social justice returns to nonfiction, nearly a decade after Between the World and Me, visiting Dakar, to contemplate enslavement and the Middle Passage; Columbia, S.C., as a backdrop for his thoughts on Jim Crow and book bans; and the Israeli-occupied West Bank, where he sees contemporary segregation in the treatment of Palestinians.

Who it’s for: Fans of James Baldwin, George Orwell, and Angela Y. Davis; readers of Nikole Hannah-Jones’s The 1619 Project and Isabel Wilkerson’s Caste, to name just a few engagements with national and racial identity. —Nathalie op de Beeck

Abortion by Jessica Valenti [NF]

What it is: Columnist and memoirist Valenti, who tracks pro-choice advocacy and attacks on the right to choose in her Substack, channels feminist rage into a guide for freedom of choice advocacy.

Who it’s for: Readers of Robin Marty’s The New Handbook for a Post-Roe America, #ShoutYourAbortion proponents, and followers of Jennifer Baumgartner’s [I Had an Abortion] project. —NodB

Gifted by Suzuki Suzumi, tr. Allison Markin Powell [F]

What it's about: A young sex worker in Tokyo's red-light district muses on her life and recounts her abusive mother's final days, in what is Suzuki's first novel to be translated into English.

Who it's for: Readers of Susan Boyt and Mieko Kanai; fans of moody, introspective fiction; anyone with a fraught relationship to their mother. —SMS

Childish Literature by Alejandro Zambra, tr. Megan McDowell [F]

What it is: A wide-ranging collection of stories, essays, and poems that explore childhood, fatherhood, and family.

Who it's for: Fans of dad lit (see: Lucas Mann's Attachments, Keith Gessen's Raising Raffi, Karl Ove Knausgaard's seasons quartet, et al). —SMS

Books Are Made Out of Books ed. Michael Lynn Crews [NF]

What it is: A mining of the archives of the late Cormac McCarthy with a focus on the famously tight-lipped author's literary influences.

Who it's for: Anyone whose commonplace book contains the words "arquebus," "cordillera," or "vinegaroon." —JHM

Slaveroad by John Edgar Wideman [F]

What it is: A blend of memoir, fiction, and history that charts the "slaveroad" that runs through American history, spanning the Atlantic slave trade to the criminal justice system, from the celebrated author of Brothers and Keepers.

Who it's for: Fans of Clint Smith and Ta-Nehisi Coates. —SMS

Linguaphile by Julie Sedivy [NF]

What it's about: Linguist Sedivy reflects on a life spent loving language—its beauty, its mystery, and the essential role it plays in human existence.

Who it's for: Amateur (or professional) linguists; fans of the podcast A Way with Words (me). —SMS

An Image of My Name Enters America by Lucy Ives [NF]

What it is: A collection of interrelated essays that connect moments from Ives's life to larger questions of history, identity, and national fantasy,

Who it's for: Fans of Ives, one of our weirdest and most wondrous living writers—duh; anyone with a passing interest in My Little Pony, Cold War–era musicals, or The Three Body Problem, all of which are mined here for great effect. —SMS

Women's Hotel by Daniel Lavery [F]

What it is: A novel set in 1960s New York City, about the adventures of the residents of a hotel providing housing for young women that is very much evocative of the real-life legendary Barbizon Hotel.

Who it's for: Readers of Mary McCarthy's The Group and Rona Jaffe's The Best of Everything. —CK

The World in Books by Kenneth C. Davis [NF]

What it is: A guide to 52 of the most influential works of nonfiction ever published, spanning works from Plato to Ida B. Wells, bell hooks to Barbara Ehrenreich, and Sun Tzu to Joan Didion.

Who it's for: Lovers of nonfiction looking to cover their canonical bases. —SMS

Blue Light Hours by Bruna Dantas Lobato [F]

What it's about: Through the emanating blue-glow of their computer screens, a mother and daughter, four-thousand miles apart, find solace and loneliness in their nightly Skype chats in this heartstring-pulling debut.

Who it's for: Someone who needs to be reminded to CALL YOUR MOTHER! —DF

Riding Like the Wind by Iris Jamahl Dunkle [NF]

What it is: The biography of Sanora Babb, a contemporary of John Steinbeck's whose field notes and interviews with Dust Bowl migrants Steinbeck relied upon to write The Grapes of Wrath.

Who it's for: Steinbeck fans and haters alike; readers of Kristin Hannah's The Four Winds and the New York Times Overlooked column; anyone interested in learning more about the Dust Bowl migrants who fled to California hoping for a better life. —CK

Innie Shadows by Olivia M. Coetzee [F]

What it is: a work of crime fiction set on the outskirts of Cape Town, where a community marred by violence seeks justice and connection; also the first novel to be translated from Kaaps, a dialect of Afrikaans that was until recently only a spoken language.

Who it's for: fans of sprawling, socioeconomically-attuned crime dramas a la The Wire. —SMS

Dorothy Parker in Hollywood by Gail Crowther [NF]

What it is: A history of the famous wit—and famous New Yorker—in her L.A. era, post–Algonquin Round Table and mid–Red Scare.

Who it's for: Owners of a stack of hopelessly dog-eared Joan Didion paperbacks. —JHM

The Myth of American Idealism by Noam Chomsky and Nathan J. Robinson [NF]

What it is: A potent critique of the ideology behind America's foreign interventions and its status as a global power, and an treatise on how the nation's hubristic pursuit of "spreading democracy" threatens not only the delicate balance of global peace, but the already-declining health of our planet.

Who it's for: Chomskyites; policy wonks and casual critics of American recklessness alike. —DF

Mysticism by Simon Critchley [NF]

What it is: A study of mysticism—defined as an experience, rather than religious practice—by the great British philosopher Critchley, who mines music, poetry, and literature along the way.

Who it's for: Readers of John Gray, Jorge Luis Borges, and Simone Weil. —SMS

Q&A by Adrian Tomine [NF]

What it is: The Japanese American creator of the Optic Nerve comic book series for D&Q, and of many a New Yorker cover, shares his personal history and his creative process in this illustrated unburdening.

Who it’s for: Readers of Tomine’s melancholic, sometimes cringey, and occasionally brutal collections of comics short stories including Summer Blonde, Shortcomings, and Killing and Dying. —NodB

Sonny Boy by Al Pacino [NF]

What it is: Al Pacino's memoir—end of description.

Who it's for: Cinephiles; anyone curious how he's gonna spin fumbling Diane Keaton. —SMS

Seeing Baya by Alice Kaplan [NF]

What it is: The first biography of the enigmatic and largely-forgotten Algerian artist Baya Mahieddine, who first enchanted midcentury Paris as a teenager.

Who it's for: Admirers of Leonora Carrington, Hilma af Klint, Frida Kahlo, and other belatedly-celebrated women painters. —SMS

Absolution by Jeff VanderMeer [F]

What it is: A surprise return to the Area X, the stretch of unforbidding and uncanny coastline in the hit Southern Reach trilogy.

Who it's for: Anyone who's heard this song and got the reference without Googling it. —JHM

The Four Horsemen by Nick Curtola [NF]

What it is: The much-anticipated cookbook from the team behind Brooklyn's hottest restaurant (which also happens to be co-owned by James Murphy of LCD Soundsystem).

Who it's for: Oenophiles; thirty-somethings who live in north Williamsburg (derogatory). —SMS

Seeing Further by Esther Kinsky, tr. Caroline Schmidt [F]

What it's about: An unnamed German woman embarks on the colossal task of reviving a cinema in a small Hungarian village.

Who it's for: Fans of Jenny Erpenbeck; anyone charmed by Cinema Paradiso (not derogatory!). —SMS

Ripcord by Nate Lippens [NF]

What it's about: A novel of class, sex, friendship, and queer intimacy, written in delicious prose and narrated by a gay man adrift in Milwaukee.

Who it's for: Fans of Brontez Purnell, Garth Greenwell, Alexander Chee, and Wayne Koestenbaum. —SMS

The Use of Photography by Annie Ernaux and Marc Marie, tr. Alison L. Strayer [NF]

What it's about: Ernaux's love affair with Marie, a journalist, while she was undergoing treatment for cancer, and their joint project to document their romance.

Who it's for: The Ernaux hive, obviously; readers of Sontag's On Photography and Janet Malcolm's Still Pictures. —SMS

Nora Ephron at the Movies by Ilana Kaplan [NF]

What it is: Kaplan revisits Nora Ephron's cinematic watersheds—Silkwood, Heartburn, When Harry Met Sally, You've Got Mail, and Sleepless in Seattle—in this illustrated book. Have these iconic stories, and Ephron’s humor, weathered more than 40 years?

Who it’s for: Film history buffs who don’t mind a heteronormative HEA; listeners of the Hot and Bothered podcast; your coastal grandma. —NodB

[millions_email]

The Philosophy of Translation by Damion Searls [NF]

What it is: A meditation on the act and art of translation by one of today's most acclaimed practitioners, best known for his translations of Fosse, Proust, et al.

Who it's for: Regular readers of Words Without Borders and Asymptote; professional and amateur literary translators alike. —SMS

Salvage by Dionne Brand

What it is: A penetrating reevaluation of the British literary canon and the tropes once shaped Brand's reading life and sense of self—and Brand’s first major work of nonfiction since her landmark A Map to the Door of No Return.

Who it's for: Readers of Christina Sharpe's Ordinary Notes and Elizabeth Hardwick's Seduction and Betrayal. —SMS

Masquerade by Mike Fu [F]

What it's about: Housesitting for an artist friend in present-day New York, Meadow Liu stumbles on a novel whose author shares his name—the first of many strange, haunting happenings that lead up to the mysterious disappearance of Meadow's friend.

Who it's for: fans of Ed Park and Alexander Chee. —SMS

November

The Beggar Student by Osamu Dazai, tr. Sam Bett [F]

What it is: A novella in the moody vein of Dazai’s acclaimed No Longer Human, following the 30-something “fictional” Dazai into another misadventure spawned from a hubristic spat with a high schooler.

Who it's for: Longtime readers of Dazai, or new fans who discovered the midcentury Japanese novelist via TikTok and the Bungo Stray Dogs anime. —DF

In Thrall by Jane DeLynn [F]

What it is: A landmark lesbian bildungsroman about 16-year-old Lynn's love affair with her English teacher, originally published in 1982.

Who it's for: Fans of Joanna Russ's On Strike Against God and Edmund White's A Boy's Own Story —SMS

Washita Love Child by Douglas Kent Miller [NF]

What it is: The story of Jesse Ed Davis, the Indigenous musician who became on of the most sought after guitarists of the late '60s and '70s, playing alongside B.B. King, Bob Dylan, John Lennon, and more.

Who it's for: readers of music history and/or Indigenous history; fans of Joy Harjo, who wrote the foreword. —SMS

Set My Heart on Fire by Izumi Suzuki, tr. Helen O'Horan [F]

What it is: Gritty, sexy, and wholly rock ’n’ roll, Suzuki’s first novel translated into English (following her story collection, Hit Parade of Tears) follows 20-year-old Izumi navigating life, love, and music in the underground scene in '70s Japan.

Who it's for: Fans of Meiko Kawakami, Ursula K. Le Guin, and Marlowe Granados's Happy Hour. —DF

Didion & Babitz by Lili Anolik [NF]

What it is: A dual portrait of Joan Didion and Eve Babitz, who are so often compared to—and pitted against—each other on the basis of their mutual Los Angeles milieu.

Who it's for: Fans or haters of either writer (the book is fairly pro-Babitz, often at Didion's expense); anyone who has the Lit Hub Didion tote bag. —SMS

The Endless Refrain by David Rowell [NF]

What it's about: How the rise of music streaming, demonitizing of artist revenue, and industry tendency toward nostalgia have laid waste to the musical landscape, and the future of music culture.

Who it's for: Fans of Kyle Chayka, Spence Kornhaber, and Lindsay Zoladz. —SMS

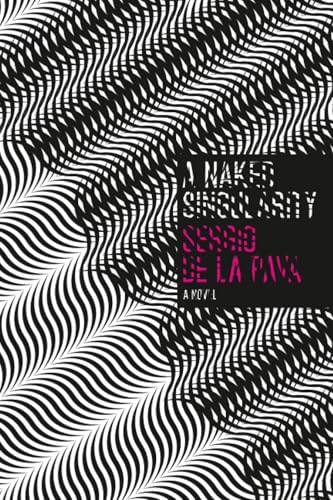

Every Arc Bends Its Radian by Sergio De La Pava [F]

What it is: A mind- and genre-bending detective story set in Cali, Colombia, that blends high-stakes suspense with rigorous philosophy.

Who it's for: Readers of Raymond Chandler, Thomas Pynchon, and Jules Verne. —SMS

Something Close to Nothing by Tom Pyun [F]

What it’s about: At the airport with his white husband Jared, awaiting a flight to Cambodia to meet the surrogate mother carrying their adoptive child-to-be, Korean American Wynn decides parenthood isn't for him, and bad behavior ensues.

Who it’s for: Pyun’s debut is calculated to cut through saccharine depictions of queer parenthood—could pair well with Torrey Peters’s Detransition, Baby. —NodB

Rosenfeld by Maya Kessler [F]

What it is: Kessler's debut—rated R for Rosenfeld—follows one Noa Simmons through the tumultuous and ultimately profound power play that is courting (and having a lot of sex with) the titular older man who soon becomes her boss.

Who it's for: Fans of Sex and the City, Raven Leilani’s Luster, and Coco Mellor’s Cleopatra and Frankenstein. —DF

Lazarus Man by Richard Price [F]

What it is: The former The Wire writer offers yet another astute chronicle of urban life, this time of an ever-changing Harlem.

Who it's for: Fans of Colson Whitehead's Crook Manifesto and Paul Murray's The Bee Sting—and, of course, The Wire. —SMS

Stranger Than Fiction by Edwin Frank [NF]

What it is: An astute curveball of a read on the development and many manifestations of the novel throughout the tumultuous 20th century.

Who it's for: Readers who look at a book's colophon before its title. —JHM

Letters to His Neighbor by Marcel Proust, tr. Lydia Davis

What it is: A collection of Proust’s tormented—and frequently hilarious—letters to his noisy neighbor which, in a diligent translation from Davis, stand the test of time.

Who it's for: Proust lovers; people who live below heavy-steppers. —DF

Context Collapse by Ryan Ruby [NF]

What it is: A self-proclaimed "poem containing a history of poetry," from ancient Greece to the Iowa Workshop, from your favorite literary critic's favorite literary critic.

Who it's for: Anyone who read and admired Ruby's titanic 2022 essay on The Waste Land; lovers of poetry looking for a challenge. —SMS

How Sondheim Can Change Your Life by Richard Schoch [NF]

What it's about: Drama professor Schoch's tribute to Stephen Sondheim and the life lessons to be gleaned from his music.

Who it's for: Sondheim heads, former theater kids, end of list. —SMS

The Serviceberry by Robin Wall Kimmerer [NF]

What it is: 2022 MacArthur fellow and botanist Kimmerer, an enrolled member of the Citizen Potawatomi Nation, (re)introduces audiences to a flowering, fruiting native plant beloved of foragers and gardeners.

Who it’s for: The restoration ecologist in your life, along with anyone who loved Braiding Sweetgrass and needs a nature-themed holiday gift. —NodB

My Heart Belongs in an Empty Big Mac Container Buried Beneath the Ocean Floor by Homeless [F]

What it is: A pseudonymous, tenderly comic novel of blue whales and Golden Arches, mental illness and recovery.

Who it's for: Anyone who finds Thomas Pynchon a bit too staid. —JHM

Yoke and Feather by Jessie van Eerden [NF]

What it's about: Van Eerden's braided essays explore the "everyday sacred" to tease out connections between ancient myth and contemporary life.

Who it's for: Readers of Courtney Zoffness's Spilt Milk and Jeanna Kadlec's Heretic. —SMS

Camp Jeff by Tova Reich [F]

What it's about: A "reeducation" center for sex pests in the Catskills, founded by one Jeffery Epstein (no, not that one), where the dual phenomena of #MeToo and therapyspeak collide.

Who it's for: Fans of Philip Roth and Nathan Englander; cancel culture skeptics. —SMS

Selected Amazon Reviews by Kevin Killian [NF]

What it is: A collection of 16 years of Killian’s funniest, wittiest, and most poetic Amazon reviews, the sheer number of which helped him earn the rarefied “Top 100” and “Hall of Fame” status on the site.

Who it's for: Fans of Wayne Koestenbaum and Dodie Bellamy, who wrote introduction and afterword, respectively; people who actually leave Amazon reviews. —DF

Cher by Cher [NF]

What it is: The first in a two-volume memoir, telling the story of Cher's early life and ascendent career as only she can tell it.

Who it's for: Anyone looking to fill the My Name Is Barbra–sized hole in their heart, or looking for something to tide them over until the Liza memoir drops. —SMS

The City and Its Uncertain Walls by Haruki Murakami, tr. Philip Gabriel [F]

What it is: Murakami’s first novel in over six years returns to the high-walled city from his 1985 story "Hard-Boiled Wonderland and the End of the World" with one man's search for his lost love—and, simultaneously, an ode to libraries and literature itself.

Who it's for: Murakami fans who have long awaited his return to fiction. —DF

American Bulk by Emily Mester [NF]

What it's about: Reflecting on what it means to "live life to the fullest," Mester explores the cultural and personal impacts of America’s culture of overconsumption, from Costco hauls to hoarding to diet culture—oh my!

Who it's for: Lovers of sustainability; haters of excess; skeptics of the title essay of Becca Rothfeld's All Things Are Too Small. —DF

The Icon and the Idealist by Stephanie Gorton [NF]

What it is: A compelling look at the rivalry between Margaret Sanger, of Planned Parenthood fame, and Mary Ware Dennett, who each held radically different visions for the future of birth control.

Who it's for: Readers of Amy Sohn's The Man Who Hated Women and Katherine Turk's The Women of NOW; anyone interested in the history of reproductive rights. —SMS

December

Rental House by Weike Wang [F]

What it's about: Married college sweethearts invite their drastically different families on a Cape Code vacation, raising questions about marriage, intimacy, and kinship.

Who it's for: Fans of Wang's trademark wit and sly humor (see: Joan Is Okay and Chemistry); anyone with an in-law problem.

Woo Woo by Ella Baxter [F]

What it's about: A neurotic conceptual artist loses her shit in the months leading up to an exhibition that she hopes will be her big breakout, poking fun at the tropes of the "art monster" and the "woman of the verge" in one fell, stylish swoop.

Who it's for: Readers of Sheena Patel's I'm a Fan and Chris Kraus's I Love Dick; any woman who is grateful to but now also sort of begrudges Jenny Offil for introducing "art monster" into the lexicon (me). —SMS

Berlin Atomized by Julia Kornberg, tr. Jack Rockwell and Julia Kornberg [F]

What it's about: Spanning 2001 to 2034, three Jewish and downwardly mobile siblings come of age in various corners of the world against the backdrop of global crisis.

Who it's for: Fans of Catherine Lacey's Biography of X and Joshua Cohen's The Netanyahus. —SMS

Sand-Catcher by Omar Khalifah, tr. Barbara Romaine [F]

What it is: A suspenseful, dark satire of memory and nation, in which four young Palestinian journalists at a Jordanian newspaper are assigned to interview an elderly witness to the Nakba, the violent 1948 expulsion of native Palestinians from Israel—but to their surprise, the survivor doesn’t want to rehash his trauma for the media.

Who it’s for: Anyone looking insight—tinged with grim humor—into the years leading up to the present political crisis in the Middle East and the decades-long goal of Palestinian autonomy. —NodB

The Shutouts by Gabrielle Korn [F]

What it's about: In the dystopian future, mysteriously connected women fight to survive on the margins of society amid worsening climate collapse.

Who it's for: Fans of Korn's Yours for the Taking, which takes place in the same universe; readers of Becky Chambers and queer-inflected sci-fi. —SMS

What in Me Is Dark by Orlando Reade [NF]

What it's about: The enduring, evolving influence of Milton's Paradise Lost on political history—and particularly on the work of 12 revolutionary readers, including Malcom X and Hannah Arendt.

Who it's for: English majors and fans of Ryan Ruby and Sarah Bakewell—but I repeat myself. —SMS

The Afterlife Is Letting Go by Brandon Shimoda [NF]

What it's about: Shimoda researches the mass incarceration of Japanese Americans during WWII, and speaks with descendants of those imprisoned, for this essay collection about the “afterlife” of cruelty and xenophobia in the U.S.

Who it’s for: Anyone to ever visit a monument, museum, or designated site of hallowed ground where traumatic events have taken place. —NodB

No Place to Bury the Dead by Karina Sainz Borgo, tr. Elizabeth Bryer [F]

What it's about: When Angustias Romero loses both her children while fleeing a mysterious disease in her unnamed Latin American country, she finds herself in a surreal, purgatorial borderland where she's soon caught in a power struggle.

Who it's for: Fans of Maríana Enriquez and Mohsin Hamid. —SMS

The Rest Is Silence by Augusto Monterroso, tr. Aaron Kerner [F]

What it is: The author of some of the shortest, and tightest, stories in Latin American literature goes long with a metafictional skewering of literary criticism in his only novel.

Who it's for: Anyone who prefers the term "palm-of-the-hand stories" to "flash fiction." —JHM

Tali Girls by Siamak Herawi, tr. Sara Khalili [F]

What it is: An intimate, harrowing, and vital look at the lives of girls and women in an Afghan mountain village under Taliban rule, based on true stories.

Who it's for: Readers of Nadia Hashimi, Akwaeke Emezi, and Maria Stepanova. —SMS

Sun City by Tove Jansson, tr. Thomas Teal [F]

What it's about: During her travels through the U.S. in the 1970s, Jansson became interested in the retirement home as a peculiarly American institution—here, she imagines the tightly knit community within one of them.

Who it's for: Fans of Jansson's other fiction for adults, much of which explores the lives of elderly folks; anyone who watched that documentary about The Villages in Florida. —SMS

Editor's note: We're always looking to make our seasonal book previews more useful to the readers, writers, and critics they're meant to serve. Got an idea for how we can improve our coverage? Tell me about it at sophia@themillions.com.

[millions_email]

A Bloodletting: On Mark Doten’s ‘The Infernal’

In an essay for the Los Angeles Review of Books, the writer and Iraq War veteran Roy Scranton outlined what he called “the myth of the trauma hero.” It goes like this:

Every true war story is a story of trauma and recovery. A boy goes to war, his head full of romantic visions of glory, courage, and sacrifice, his heart yearning to achieve heroic deeds, but on the field of battle he finds only death and horror. He sees, suffers, and causes brutal and brutalizing violence. Such violence wounds the soldier’s very soul.

After the war the boy, now a veteran and a man, returns to the world of peace haunted by his experience, wracked by the central compulsion of trauma and atrocity: the struggle between the need to bear witness to his shattering encounter with violence, and the compulsion to repress it. The veteran tries to make sense of his memory but finds it all but impossible. Most people don’t want to hear the awful truths that war has taught him, the political powers that be want to cover up the shocking reality of war, and anybody who wasn’t there simply can’t understand what it was like.

The truth of war, the veteran comes to learn, is a truth beyond words, a truth that can only be known by having been there, an unspeakable truth he must bear for society.

So goes the myth of the trauma hero.

Scranton locates the origins of this myth in the 18-century Romanticism that valued individual experience above all else. He tracks the myth through two world wars, Vietnam, and up to the United States's most recent conflicts in Iraq and Afghanistan. The last few years have seen an outpouring of memoirs, novels, and films about these two wars, and many of the most commercially and critically successful offer their own take on the trauma hero. Scranton, however, finds this myth dangerous, saying that it “serves a scapegoat function, discharging national bloodguilt by substituting the victim of trauma, the soldier, for the victim of violence, the enemy.” He doesn’t fault the writers of such narratives as much as their readers, eager to honor the tales told by trauma heroes, and in so doing avoid hearing stories of war that detail the victims of violence, and -- more to the point -- those responsible for it.

The Infernal, a novel by Mark Doten, seeks to tell that kind of story, one that accounts for those involved in the War on Terror at nearly every level, from the grunts lugging 80-pound packs to the residents of dusty villages on the other side of the world to the highest echelons of American power. I fear that this description, however, might give the impression that the book has the dutiful, even-handed tone of an episode of Frontline. That is not the case. The Infernal is certifiably insane, a monstrous, cartoon nightmare of a book.

Open up the book, and you’ll find a “Dramatis Personae” section, like in a 19th-century Russian novel. This one doesn’t track family trees and patronymics, however; characters include Dick Cheney, Condoleeza Rice, and Mark Zuckerberg, as well as more inscrutable entries for “The Omnosyne” and “The Memex.” What is going on? Is this a postmodern swipe at American society like Robert Coover’s The Public Burning, a novelization of the Rosenberg trial that featured Richard Nixon as its protagonist? A gloss on celebrity like Bruce Wagner’s Dead Stars, in which Michael Douglas appears as a hologram of a character? The action and language of The Infernal are of the moment, but you might have to go all the way back to the novel’s namesake to get an idea of what Doten is up to. In The Inferno, Dante Alighieri placed all his enemies from 14th-century Florence in Hell, where they gave accounts of their sins while suffering elaborate, ironic punishments. Doten wants to place these historical figures in his fiction where they will be forced to explain themselves, as this is unlikely to happen in the real world.

The novel begins in the Akkad Valley of Iraq, at a geological formation known as Al-Madkhanah, or the Chimney. Strange clouds appear at the peak of the Chimney. A patrol of soldiers goes to investigate. One of them climbs to the top, where he discovers a boy burned almost beyond recognition. The soldiers return the boy to a base. He cannot speak, sign, or communicate in any way. But the Commission, a shadowy organization that seems to catalog and thus control the world, needs the information that the boy has. They decide to bring the traitor Jimmy Wales out of prison so he can use his invention, the Omnosyne, to extract a confession from the boy.

Jimmy Wales? Isn’t that the guy who created Wikipedia? That is indeed who he is IRL, as they say, but in the universe of The Infernal, Wales was a student at Dr. Vannevar Bush’s Institute for Youth Advances, where he helped create the Memex, a worldwide network of knowledge that served as a kind of precursor to the Internet, except it was only available to the Commission. Wales broke with Dr. Bush and the Institute, however, when he invented the Omnosyne, an information-gathering tool that is half lie detector, half torture device. To use the Omnosyne, an elaborate system of wires are inserted into the subject’s tongue and spine, extracting the essential information from his very nerves and bones. The wires are hooked up to what looks like a typewriter, printing out the subject’s confession in Omnotic Code, which only Wales can decipher. Once he created the Omnosyne, however, Wales killed a dozen instructors at the Institute for Youth Advances, at which point the Commission placed him in jail for life and mothballed the Omnosyne. The Commission is desperate for the Akkad Boy’s confession, however, so they bring Wales and his device to the Akkad Valley.

Due to the invasive nature of the Omnosyne, an extraction results in the death of the subject. This is deemed acceptable, as the Akkad Boy’s confession will surely prove invaluable. When Wales hooks him up to the Omnosyne and begins the extraction, however, the pages that are printed out in Omnotic Code give not the boy’s confession, but rather the confessions of a host of different people, all involved in the War on Terror in one way or another: Osama Bin Laden, L. Paul Bremer, an Iraqi woman named Noor, and on and on. These polysyllabic confessions form the text of The Infernal, which can read as if William Faulkner were blogging about current events, as in this passage written from the perspective of Bremer, Presidential Envoy to Iraq.

Not much in the way of running water, friends, mostly this here’s a porta-potty town, Jay told us, I told Condi on the cell.

Meanwhile Saddam flew past . . .

Meanwhile Saddam flew right past us . . .

And meanwhile Saddam in statue form, poster form, some billboards, too, and murals of Saddam, that sonofabitch just kept on flying on past us, One hell, I said, one hell of an Ozymandian tribute, Jay with no idea, Florida State University, then Shippensburg, never overcame those early obstacles...

Elsewhere, Osama Bin Laden, holed up in a cave, has his followers construct a new dialysis machine, which quickly devolves into violent slapstick; two drone-strike survivors named Rashid and Hakim stumble around like Laurel and Hardy; US Attorney General Alberto Gonzalez crawls through the air ducts of Guantanamo; Iraq War Veteran Tom Pally hobbles around his ranch house on an artificial leg, trying to make dinner plans for his and his wife’s anniversary, instead getting accosted by the vengeful maitre d’ of the restaurant. In the background of all this, there are intimations of a New City coming into being, a realm of pure information that the Commission plans to upload themselves into, leaving behind the corporeal world.

At this point in the review, I’m guessing that you either really want to read The Infernal, or you really don’t. It seems like an ideal object for the enthusiastic scholarship of a devoted cult, and I sincerely look forward to the WikiLink page that will explain all of the book’s mysteries. But Doten has written his idiosyncratic book about events that will be familiar to many, perhaps even overly familiar, and it’s worth asking why.

Part of an answer may lie in Doten’s biography. Doten is currently the literary editor at Soho Press, the publishing house whose renaissance The Millions covered last year. Before that, Doten was an associate editor at The Huffington Post, working for the site at its very beginning in 2005. (Andrew Breitbart was one of the site’s cofounders, though he soon left after a falling-out with Arianna Huffington, and The Infernal has a great, nasty joke made at his expense.) Doten is sure to have edited hundreds, maybe even thousands, of stories about the War on Terror and its many players, to the point where they very well might have seemed less like human beings and more like hallucinations, the characters in a compensatory power fantasy dreamed up by a traumatized, vengeful public. That’s not the kind of story you can tell as a journalist, however, and it’s possible Doten looked to the role of novelist as a way of telling the deeper, spiritual truth about our disastrous recent history, the kind of truth that fiction is still best-equipped to tell.

Debts to postmodern fiction aside, the book that The Infernal most reminded me of was George Packer’s The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New America. Packer’s book is nonfiction, drawing on extensive interviews with ordinary citizens (remember when journalists did that?) as well as secondary sources for accounts of big name movers and shakers, but it’s structured very much like a novel, using the stories of its constituent characters to tell a larger, cohesive story about our current social reality, and what led to it. In fact, Packer explicitly modeled his book on novelist John Dos Passos’s U.S.A. trilogy, an account of the tumultuous events of the early part of the 20th century.[1] Packer’s goal in the book is quixotic, using the tools of serious journalism to try and offer a diagnosis of the sickness afflicting the body politic, the reporter doing the work of the artist.

Doten also thinks that 21st-century America is sick, but The Infernal isn’t a diagnosis. It’s a bloodletting. As the Omnosyne extracts the Akkad Boy’s confession and the voices of those in power and the powerless inculpate themselves with every profession of innocence, the reader has the sense that all the lies and deceit of the last dozen years, the courage shown and the suspicion that it meant little, have been brought together in one place, between the covers of a single book. Here’s hoping that people open it.

[1] A little inside baseball: Scranton’s essay is, in part, a response to George Packer’s essay on recent books about the Iraq and Afghanistan Wars for The New Yorker. Scranton takes Packer to task for only considering works that fulfill the trauma hero myth “while ignoring works that don’t fit that frame, such as John Dos Passos’s epic U.S.A. trilogy.” Writer, read thyself.

A Year in Reading: Garth Risk Hallberg

This year, for the first time since I was 18, I suffered a bout of what you might call Reader's Block. It hit me in the spring and lasted about six weeks. The proximate cause was an excess of work, hunched hours in front of a computer that left me feeling like a jeweler's loupe was lodged in each eye. I'd turn to the door of my study -- Oh, God! An axe-wielding giant! No, wait: that's just my two year old, offering a mauled bagel. And because the only prose that doesn't look comparably distorted at that level of magnification belongs to E.B. White, Gertrude Stein, and whoever wrote the King James Bible, I mostly confined myself to the newspaper, when I read anything at all.

This hiatus from literature gave me a new compassion for people who glance up from smartphones to tell me they're too busy to read, and for those writers (students, mostly) who claim to avoid other people's work when they're working. Yet I found that for me, at least, the old programmer's maxim applies: Garbage In, Garbage Out. I mean this not just as someone with aesthetic aspirations, or pretensions, or whatever, but also as a human being.

The deeper cause of my reader's block, I can admit now, was my father's death at the end of May, after several years of illness. He was a writer, too; he'd published a novel when he was about the age I am now, and subsequently a travelogue. And maybe I had absorbed, over the years, some of his misapprehensions about what good writing might accomplish, vis-a-vis mortality; maybe I was now rebelling against the futility of the whole enterprise. I don't know. I do know that in the last weeks before he died, those weeks of no reading, I felt anxious, adrift, locked inside my grief.

Then in June, on some instinct to steer into the skid, I reached for Henderson the Rain King. It was the last of the major Bellows I hadn't read. I'd shied away partly for fear of its African setting, but mostly because it was the Saul Bellow book my father would always recommend. I'd say I was reading Humboldt's Gift, and he'd say, "But have you read Henderson the Rain King?" Or I'd say I was reading Middlemarch, and he'd say "Sure, but have you read Henderson the Rain King?" I'd say I was heavily into early Sonic Youth. "Okay, but there's this wonderful book..." There were times when I wondered if he'd actually read Henderson the Rain King, or if, having established that I hadn't read it, he saw it as a safe way to short-circuit any invitation into my inner life. And I suppose I was afraid that if I finally read Henderson and was unmoved, or worse, it would either confirm the hypothesis or demolish for all time my sense of my dad as a person of taste.

But of course the novel's mise-en-scène is a ruse (as Bellow well knew, never having been to Africa). Or if that still sounds imperialist, a dreamscape. Really, the whole thing is set at the center of a battered, lonely, yearning, and comical human heart. A heart that says, "I want, I want, I want." A heart that could have been my father's. Or my own. And though that heart doesn't get what it wants -- that's not its nature -- it gets something perhaps more durable. Midway through the novel, King Dahfu of the Wariri tries to talk a woebegone Henderson into hanging out with a lion:

"What can she do for you? Many things. First she is unavoidable. Test it, and you will find she is unavoidable. And this is what you need, as you are an avoider. Oh, you have accomplished momentous avoidances. But she will change that. She will make consciousness to shine. She will burnish you. She will force the present moment upon you. Second, lions are experiences. But not in haste. They experience with deliberate luxury...Then there are more subtle things, as how she leaves hints, or elicits caresses. But I cannot expect you to see this at first. She has much to teach you."

To which Henderson replies: "‘Teach? You really mean that she might change me.’"

"‘Excellent,'" the king says:

"Precisely. Change. You fled what you were. You did not believe you had to perish. Once more, and a last time, you tried the world. With a hope of alteration. Oh, do not be surprised by such a recognition."

The lion stuff in Henderson, like the tennis stuff in Infinite Jest, inclines pretty nakedly toward ars poetica. Deliberate luxury, burnished consciousness, a sense of inevitability -- aren't these a reader's hopes, too? And then: the deep recognition, the resulting change. Henderson the Rain King gave me all that, at the time when I needed it most. Then again, such a recognition is always surprising, because it's damn hard to come by. And so, though I'm already at 800 words here, I'd like to list some of my other best reading experiences of 2014 (the back half of which amounted to a long, post-Henderson binge). Maybe one of them will do for you what that lion did for me.

Light Years, by James Salter

Despite the eloquent advocacy of my Millions colleague Sonya Chung, I'd always had this idea of James Salter as some kind of Mandarin, a writer for other writers. But I read Light Years over two days in August, and found it a masterpiece. The beauty of Salter's prose -- and it is beautiful -- isn't the kind that comes from fussing endlessly over clauses, but the kind that comes from looking up from the page, listening hard to whatever's beyond. And what Light Years hears, as the title suggests, is time passing, the arrival and inevitable departure of everything dear to us. It is music like ice cracking, a river in the spring.

The Prime of Miss Jean Brodie, by Muriel Spark

I've long known I should read Muriel Spark, but it took the republication of some of her backlist (by New Directions) to get me off the fence. Spark shares with Salter a sublime detachment, an almost Olympian view of the passage of time. This latter seems to be her real subject in Miss Jean Brodie, inscribed even in the dazzling structure of the novel. But unlike Salter, Spark is funny. Really funny. Her reputation for mercilessness is not unearned, but the comedy here is deeper, I think. As in Jonathan Franzen's novels, it issues less from the exposure of flawed and unlikeable characters than from the author's warring impulses: to see them clearly, vs. to love them. Ultimately, in most good fiction, these amount to the same thing.

The Unbearable Lightness of Being, by Milan Kundera

This was a popular novel among grown-ups when I was a kid, and so I was pleasantly surprised to discover how stubborn and weird a work it is. And lovable for all that. Kundera keeps us at a peculiar distance from his protagonists, almost as if telling a fairy tale. Description is sparing. Plot is mostly sex. Also travel. At times, I had to remind myself which character was which. In a short story, this might be a liability. Yet somehow, over the length of the novel, through nuances of juxtaposition and patterning, Kundera manages to evoke states of feeling I've never seen on the page before. Political sadness. Emotional philosophy. The unbearable lightness of the title. All of this would seem to be as relevant in the U.S. in 2015 as in 1970s Prague.

The Infatuations, by Javier Marías

Hari Kunzru has captured, in a previous Year in Reading entry, how forbidding Javier Marías's novels can seem from a distance. (Though maybe this is true of all great stylists. Lolita, anyone?) Marías is a formidably cerebral writer, whose long sentences are like fugues: a theme is introduced, toyed with, pursued to another theme, put down, taken up again. None of this screams pleasure. But neither would a purely formal description of an Alfred Hitchcock movie. The tremendous pleasure of The Infatuations, Marías's most recent novel to appear in English, arrives from those most uncerebral places: plot, suspense, character. It's like a literary version of Strangers on a Train, cool formal mastery put to exquisitely visceral effect. "Don't open that door, Maria!" The Infatuations is the best new novel I read all year; I knew within the first few pages that I would be reading every book Mariás has written.

All the Birds, Singing, by Evie Wyld

This haunting, poetic novel manages to convey in a short space a great deal about compulsion and memory and the human capacity for good and evil. Wyld's narrator, Jake, is one of the most distinctive and sympathetic heroines in recent literature, a kind of Down Under Huck Finn. Her descriptions of the Australian outback are indelible. And the novel's backward-and-forward form manages a beautiful trick: it simultaneously dramatizes the effects of trauma and attends to our more literary hungers: for form, for style. It reminded me forcefully of another fine book that came out of the U.K. this year, Eimear McBride's A Girl is a Half-Formed Thing.

Wolf Hall and Bring Up the Bodies, by Hilary Mantel

I'd be embarrassed at my lateness to the Thomas Cromwell saga, were I not so glad to have finally made it. Mantel's a serious enough historical novelist not to shy away from those conventions of the genre that usually turn me off; the deliberate pacing of her trilogy-in-progress requires some getting used to. But more than a chronicler, Mantel is a novelist, full-stop. She excels at pretty much everything, and plays the long game brilliantly. By the time you get into the intrigues of Bring Up the Bodies, you're flying so fast you hardly notice the beautiful calibration of the prose, or the steady deepening of the psychology, or the big thoughts the novel is thinking about pragmatism and Englishness and gender and the mystery of personality.

Dispatches, by Michael Herr

If you took the horrific public-burning scene from Wolf Hall, multiplied that by 100, put those pages in a hot-boxed Tomahawk piloted by Dr. Strangelove, and attempted to read them over the blare of the Jefferson Airplane, you'd end up with something like Dispatches. It is simultaneously one of the greatest pieces of New Journalism I've ever read and one of the greatest pieces of war writing. Indeed, each achievement enables the other. The putatively embedded journalism of our own wars already looks dated by comparison. Since the publication of Dispatches in 1977, Herr's output has been slender, but I'd gladly read anything he wrote.

White Girls, by Hilton Als

This nonfiction collection casts its gaze all over the cultural map, from Flannery O'Connor to Michael Jackson, yet even more than most criticism, it adds up to a kind of diffracted autobiography. The longest piece in the book is devastating, the second-longest tough to penetrate, but this unevenness speaks to Als's virtues as an essayist. His sentences have a quality most magazine writing suffocates beneath a veneer of glibness: the quality of thinking. That is, he seems at once to have a definite point-of-view, passionately held, and to be very much a work in progress. It's hard to think of higher praise for a critic.

Utopia or Bust, by Benjamin Kunkel

This collection of sterling essays (many of them from the London Review of Books) covers work by David Graeber, Robert Brenner, Slavoj Zizek, and others, offering a state-of-the-union look at what used to be called political economy -- a nice complement to the research findings of Thomas Piketty. Kunkel is admirably unembarrassed by politics as such, and is equally admirable as an autodidact in the field of macroeconomics. He synthesizes from his subjects one of the more persuasive accounts you'll read about how we got into the mess we're in. And his writing has lucidity and wit. Of Fredric Jameson, for example, he remarks: "Not often in American writing since Henry James can there have been a mind displaying at once such tentativeness and force."

The Origin of the Brunists, by Robert Coover

The publication this spring of a gargantuan sequel, The Brunist Day of Wrath, gave me an excuse to go back and read Coover's first novel, from 48 years ago. As a fan of his midcareer highlights, The Public Burning and Pricksongs and Descants, I was expecting postmodern glitter. Instead I got something closer to William Faulkner: tradition and modernity collide in a mining town beset by religious fanaticism. Yet with the attenuation of formal daring comes an increased access to Coover's capacity for beauty, in which he excels many of his well-known peers. Despite its (inspired) misanthropy, this is a terrific novel. I couldn't help wishing, as I did with much of what I read this year, that my old man was still around, that I might recommend it to him, and so repay the debt.

More from A Year in Reading 2014

Don't miss: A Year in Reading 2013, 2012, 2011, 2010, 2009, 2008, 2007, 2006, 2005

The good stuff: The Millions' Notable articles

The motherlode: The Millions' Books and Reviews

Like what you see? Learn about 5 insanely easy ways to Support The Millions, and follow The Millions on Twitter, Facebook, Tumblr.

June Books: A Reading List for the Month of Rituals

June is sickly sweet; it's insipid. Is that because it's so warm, or because it rhymes so easily? June / moon / spoon / balloon... But while Robert Burns happily rhymed his "red, red rose / That's newly sprung in June" with a "melody / that's sweetly played in tune," Gwendolyn Brooks burned off any sugar in the terse rhythms of "We Real Cool": the rhyme she finds for "Jazz June"? "Die soon."

Tom Nissley’s column A Reader's Book of Days is adapted from his book of the same name.

June is called "midsummer," even though it's the beginning, not the middle, of the season. It's the traditional month for weddings -- Shakespeare's Midsummer Night's Dream is overflowing with matrimony -- but it's also the home of another modern ritual, graduation day -- or, as it's more evocatively known, commencement, an ending that's a beginning. It's an occasion that brings out both hope and world-weariness in elders and advice givers. It brought David Foster Wallace, in his 2005 Kenyon College commencement address reprinted as This Is Water, perhaps as close as he ever came to the unironic statement his busy mind was striving for.

But the graduation speech is an especially potent scene in African American literature. There's the narrator's friend "Shiny" in James Weldon Johnson's Autobiography of an Ex-Colored Man, speaking to a white audience like "a gladiator tossed into the arena and bade to fight for his life," and there's Richard Wright, in his memoir Black Boy, giving a rough speech he'd composed himself instead of the one written, cynically, for him. Ralph Ellison's Invisible Man is invited to give his class speech before the town's leading white citizens, only to find himself instead pitted in a "battle royal" with his classmates, while in Maya Angelou's I Know Why the Caged Bird Sings, a young student follows a white dignitary's patronizing words to the graduates with an unprompted and subversive leading of the "Negro national anthem," "Lift Ev'ry Voice and Sing" (whose lyrics, to bring the tradition full circle, were written by none other than James Weldon Johnson).

Here is a selection of June reading for the beginnings and endings that midsummer brings:

McTeague by Frank Norris (1899)

One of American literature's most memorable -- and most disastrous -- weddings ends, after an orgy of oyster soup, stewed prunes, roast goose, and champagne, with Trina whispering to her groom, McTeague, "Oh, you must be very good to me -- very, very good to me, dear, for you're all that I have in the world now."

Ulysses by James Joyce (1922)

Five days after Joyce met Nora Barnacle on a Dublin street, and one day after she stood him up, they went on their first date. Eighteen years later, he celebrated that day -- June 16, 1904 -- with a book.

Suite Française by Irène Némirovsky (1942/2004)

After reading Colette's account of the migration out of Paris forced by the German occupation, Némirovsky remarked, "If that's all she could get out of June, I'm not worried," and continued work on her own version, "Storm in June," the first of the two sections of her fictional suite she'd survive the Nazis long enough to complete.

"The Lottery" by Shirley Jackson (1948)

It's a "clear and sunny" morning on June 27 when the men, women, and children of an unnamed village assemble to conduct their annual choosing of lots.

"The Day Lady Died" by Frank O'Hara (1959)

Writing during the lunch hour of his job at the Museum of Modern Art, O'Hara gathered the moments of his afternoon into a poem: the train schedule to Long Island, a shoeshine, the "quandariness" of choosing a book, the sweat of summer, and the memory of how Billie Holiday once took his breath away.

Blues for Mister Charlie by James Baldwin (1964) and "Where Is the Voice Coming From?" by Eudora Welty (1963)

On the day (June 12, 1963) Medgar Evers was assassinated, Baldwin vowed that "nothing under heaven would prevent" him from finishing the play he was working on, about another notorious murder of a black man in Mississippi, while Welty, on hearing of the murder in her hometown of Jackson, quickly wrote a story, told from the mind of the presumed killer, that was published in The New Yorker within weeks.

Jaws by Peter Benchley (1974)

Is the greatest beach read the one that could keep you from ever wanting to go into the water again?

Blind Ambition by John Dean (197?)

We know the story of the June 1972 Watergate break-in best from All the President's Men, but Dean's insider's memoir of how it quickly went wrong, co-written with future civil rights historian Taylor Branch, is an equally thrilling and well-told tale.

The Public Burning by Robert Coover (1977)

We've never quite known what to do with The Public Burning, Coover's wild American pageant starring Nixon, a foul and folksy Uncle Sam, and the Rosenbergs, whose June execution is at its center: it's too long, too angry, too crazy, and, for the publisher's lawyers who said it couldn't be released while its main character, the freshly deposed president, was still alive, it was too soon.

Sleepless Nights by Elizabeth Hardwick (1979)

Sleepless Nights begins in a hot, blinding June but soon fragments across time, into memories from the narrator's life -- which closely resembles Hardwick's -- and stories from the lives of others, a method that has the paradoxical effect of heightening time's power.

Clockers by Richard Price (1992)

It's often said that no modern novel can match the storytelling power of The Wire, but its creators drew inspiration from Price's novel of an unsolved summertime murder in the low-level New Jersey crack trade, and for their third season they added Price to their scriptwriting team.

When the World Was Steady by Claire Messud (1995)

Bali is hot but dry in June, while the Isle of Skye is gray and wet, at least until the weather makes yet another change. Messud's first novel follows two English sisters just on the far side of middle age who find themselves on those distant and different islands, reckoning with the choices they've made and suddenly open to the life around them.

"Brokeback Mountain" by Annie Proulx (1997)

Meeting again nearly four summers after they last parted on Brokeback Mountain, Jack Twist and Ennis del Mar are drawn together with such a jolt that Jack's teeth draw blood from Ennis's mouth.

Three Junes by Julia Glass (2002)

Three Junes might well be called "Three Funerals"--each of its three sections, set in summers that stretch across a decade, takes place in the wake of a death. But the warmth of the month in Glass's title hints at the story inside, and the way her characters hold on to life wherever they find it.

Image via circasassy/Flickr

The Ragged Spawn of E.L. Doctorow’s Ragtime

Miniatures on a Broad Canvas

At the National Book Awards ceremony in New York City on November 2, E.L. Doctorow received the Medal for Distinguished Contribution to American Letters. On that night he joined a rarefied posse of past recipients that includes Eudora Welty, Toni Morrison, Norman Mailer, John Updike, Joan Didion, Philip Roth, Gore Vidal, Stephen King, Tom Wolfe, John Ashbery, and Elmore Leonard, among others. The award formalized something legions of readers have known for more than half a century: E.L. Doctorow is a national treasure.

While I wouldn't presume to single out one of Doctorow's dozen novels or story collections as his "best" book, I do think it is fair to say that, so far, his best known and best loved work is the novel Ragtime. And I would argue that this has also been his most influential book, the one that has done more than all the others to change the way American authors approach the writing of novels.

Ragtime, like so much of Doctorow's fiction, is pinned to a particular, acutely rendered moment in American history. In other novels he has taken us back to the Wild West (Welcome to Hard Times, 1960), the Civil War (The March, 2005), post-bellum New York City (The Waterworks, 1994), the Depression (World's Fair, 1985, winner of the National Book Award; Loon Lake, 1980; and Billy Bathgate, 1989), and the Cold War (The Book of Daniel, 1971).

In Ragtime he takes us back to the years immediately preceding the First World War, when America and much of the world lived in a state of dreamy innocence, oblivious that twinned calamities loomed. The book's theme, as I read it, is that such innocence is an untenable luxury, then and now, and its inevitable loss is always laced with trauma, pain, and bloodshed. To heighten the trauma, Doctorow first builds a nearly pastoral world. Here is the novel's serene opening:

In 1902 Father built a house at the crest of the Broadview Avenue hill in New Rochelle, New York. It was a three-story brown shingle with dormers, bay windows, and a screened porch. Striped awnings shaded the windows. The family took possession of this stout manse on a sunny day in June and it seemed for some years thereafter that all their days would be warm and fair.

In just four deceptively simple sentences, Doctorow has established the novel's tone and central strategy. The key word in this passage is seemed, for it hints that this stout manse will not be able to provide the stability it promises. More subtly – and crucially – Doctorow also establishes a slippery narrative voice, which will be a key to the novel's success. When we learn that "Father" built this house, we assume that the man's son or daughter is narrating the story. Later references to "Grandfather" and "Mother" and "Mother's Younger Brother" and "the Little Boy" reinforce the familial sleight of hand. But three sentences after the intimate introduction of "Father," Doctorow switches to the impersonal third-person plural and tells us that after "the family" took possession of the house, it seemed that "their" days would be warm and fair. It is a deft shift of focus, a quiet, barely noticeable pulling back, but it gives Doctorow the freedom to have it both ways – to paint miniatures on a broad canvas. The strategy is crucial to everything that will follow.

The novel was stylistically innovative in other ways. The paragraphs are long, unbroken by quoted dialog. This allows Doctorow to immerse the reader in the seamless atmosphere of a particular place and time. In the middle of the novel's long opening paragraph, Doctorow plays the gambit that will become the novel's signature and the source of its enduring influence on the way many American novelists work right up to today: he starts injecting historical figures into his fictional world.

The gambit unfolds like this: "Across America sex and death were barely distinguishable. Runaway women died in the rigors of ecstasy. Stories were hushed up and reporters paid off by rich families. One read between the lines of the journals and gazettes. In New York City the papers were full of the shooting of the famous architect Stanford White by Harry K. Thaw, eccentric scion of a coke and railroad fortune. Harry K. Thaw was the husband of Evelyn Nesbit, the celebrated beauty who had once been Stanford White's mistress." A few lines later Emma Goldman, the revolutionary, strolls onto the page. Soon after that, Harry Houdini wrecks his car, "a black 45-horsepower Pope-Toledo Runabout," in front of the family's house in New Rochelle. Five pages in, and Doctorow is already off to the races.

In the course of the novel we'll meet the muckraking journalist Jacob Riis, Sigmund Freud, Theodore Dreiser, Archduke Franz Ferdinand, Henry Ford, J.P. Morgan, Booker T. Washington, and Emiliano Zapata. With one exception – a luncheon meeting between Ford and Morgan – the appearance of these historical figures feels unforced and plausible. Doctorow's historical research is obviously prodigious, but the reader never feels that the author is emptying his notebook or showing off. The historical details, such as Houdini's "black 45-horsepower Pope-Toledo Runabout," are chosen carefully and slipped into the narrative without fanfare. In other words, Doctorow's mastery of his material and his narrative voice prevents the novel's central conceit from sliding into mere schtick.

From Kohlhase to Kohlhaas to Coalhouse

All writing comes from other writing, and of course E.L. Doctorow was not the first writer to populate a fictional narrative with historical figures. It just seemed that way to many people when Ragtime was published, to great fanfare, in the summer of 1975.

But as Doctorow happily admitted in an interview in 1988, Ragtime sprang from a very specific source – an 1810 novella called Michael Kohlhaas by the German writer Heinrich von Kleist. The parallels between the two books are unmistakable. In Kleist's novella, the title character is based on an historical figure, a 16th-century horse dealer named Hans Kohlhase, who seeks justice when he is swindled out of two horses and a servant, a campaign that wins the support of Martin Luther but eventually leads to Kohlhass's violent death; in Doctorow's novel, the black musician Coalhouse Walker mounts an equally fierce campaign for justice when his pristine Model T is desecrated by a company of racist firemen, a campaign that wins the support of Booker T. Washington but eventually leads to Coalhouse's violent death.

"Kleist is a great master," Doctorow told the interviewer. "I was first attracted to his prose, his stories, and the location of his narrative somewhere between history and fiction... Ragtime is a quite deliberate homage. You know, writers lift things from other writers all the time. I always knew I wanted to use Michael Kohlhaas in some way, but I didn't know until my black musician was driving up the Broadview Avenue hill in his Model T Ford that the time had come to do that."

Ragtime's Ragged Spawn

I read Ragtime not as a conventional historical novel – that is, a novel that hangs its fictions on a scaffold of known events – but rather as a novel that makes selective use of historical figures and events to create its own plausible but imaginary past. Yes, Doctorow did his research and he includes factual renderings of numerous historical figures and events, but these are springboards for his imaginings, not the essence of his enterprise. Put another way, Doctorow is after truth, not mere facts. But as he set out to write the book he understood that a prevailing hunger for facts had put the art of conventional storytelling under extreme pressure. He explained it this way in a 2008 interview with New York magazine: "I did have a feeling that the culture of factuality was so dominating that storytelling had lost all its authority. I thought, If they want fact, I'll give them facts that will leave their heads spinning." And when William Shawn, editor of The New Yorker, refused to run a review of the novel, Doctorow remarked, "I had transgressed in making up words and thoughts that people never said. Now it happens almost every day. I think that opened the gates."

I think he's right. Doctorow's selective use of historical figures and events lends Ragtime its air of verisimilitude without robbing him of the freedom to imagine and distort and mythologize. It is, for a writer of fiction, the best of all possible worlds. Small wonder, then, that Doctorow's strategy, radical in 1975, is now so commonplace that it's impossible to keep up with the torrent of novels, short stories, and movies that owe a debt to his act of transgression.

(For an interesting take on how transgressions can become commonplace, go see the 100th-anniversary recreation of the Armory Show, currently at the New York Historical Society. Works by Duchamp, Matisse, and Gauguin that shocked America in 1913 – the precise moment when Ragtime is set – are now part of the Modernist canon, tame and acceptable.)

Colum McCann, the decorated Irish writer now living in New York, is among the many writers who have come around to Doctorow's way of writing novels. McCann's early fiction is loosely based on historical events but populated with fictional characters. Then in 2003 he published Dancer, a fictional telling of Rudolf Nureyev's life. McCann's National Book Award-winning novel from 2009, Let the Great World Spin, pivots on Philippe Petit's mesmerizing high-wire walk between the Twin Towers in 1974. Earlier this year, McCann published TransAtlantic, a triptych that fictionalizes the stories of three journeys across the ocean by actual historical figures: the aviators John Alcock and Arthur Brown; the abolitionist Frederick Douglass; and the former U.S. Senator and peace envoy George Mitchell. In an interview with The Guardian, McCann explained his shift toward historical figures and events over the past decade by citing a maxim from the cultural anthropologist Clifford Geertz: "The real is as imagined as the imaginary." It follows that the imagined is as real as the real. McCann added, "I said about 12 years ago that writing about biographical figures showed a sort of failure of the writer's imagination." And then? "Absolutely busted. Because then I wrote Dancer...and then more or less ever since I've been hovering in this territory."

He's not alone. Here is a list, far from exhaustive and widely varying in quality, of Ragtime's progeny, with some of the historical figures who appear in each work: Blonde by Joyce Carol Oates (Marilyn Monroe); Cloudsplitter by Russell Banks (John Brown); Quiet Dell by Jayne Anne Phillips (the mass-murderer Harry F. Powers); Hollywood by Gore Vidal (William Randolph Hearst, Warren Harding, Marion Davies, Douglas Fairbanks – not to mention Vidal's more conventional historical novels such as Lincoln, Burr and 1876); The Public Burning by Robert Coover (Julius and Ethel Rosenberg, Joe McCarthy, Richard Nixon, the Marx Brothers); Wolf Hall and Bring Up the Bodies by Hilary Mantel (King Henry VIII, Thomas Cromwell, Sir Thomas More); The Women by T.C. Boyle (Frank Lloyd Wright); DaVinci's Bicycle by Guy Davenport (Picasso, Leonardo, Joyce, and Apollinaire); Z: A Novel of Zelda Fitzgerald by Therese Anne Fowler (Zelda and Scott, Hem, Ezra Pound); Dead Stars and Still Holding by Bruce Wagner (Michael Douglas, the Kardashians, a Russell Crowe look-alike and a Drew Barrymore look-alike); The 100-Year-Old Man Who Climbed Out the Window and Disappeared by Jonas Jonasson (Franco, Truman, Stalin, Churchill, Mao); and the movies Forrest Gump (Tom Hanks meets Elvis, Bear Bryant, JFK, LBJ, and Richard Nixon) and Zelig (Woody Allen brushes up against Babe Ruth, Adolph Hitler, and others in this faux documentary, with added commentary from the real-life Susan Sontag, Saul Bellow, and Bruno Bettelheim).

The last three items on this list illustrate the dangers of the strategy Doctorow pursued in Ragtime. In each of these three works, the central character encounters historical figures by pure chance and for no good reason, other than to amuse the reader or audience, or show off the filmmaker's technical wizardry. There is nothing organic or plausible about any of these contrived encounters, and they drag the works down to the level of mere schtick.

On the other end of spectrum is one of Ragtime's worthiest successors, the under-appreciated 1990 novel Silver Light by David Thomson, a writer best known for A Biographical Dictionary of Film. The novel takes the central conceit of Ragtime – fictional characters interacting with historical figures – and then gives it a delicious twist. Using the medium he knows so well, the movies, Thomson gives us a rambling cast of characters, a mix of real and imagined people and – here's the twist – the actors who played some of them in movies. It was not until I read the extensive Note on Characters at the end of the book that I understood the histories of these people. The character Noah Cross, for instance, was lifted directly from the 1974 movie Chinatown. The (real? imagined?) character Susan Garth is the cantankerous 80-year-old daughter of a cattle rancher named Matthew Garth, who was played by Montgomery Clift in the 1948 Howard Hawks movie Red River, which was based on a Saturday Evening Post story by Borden Chase. Thomson makes superb use of this layered source material. In a scene that goes to the heart of such fiction, Thomson puts Susan Garth on the Red River set outside Willcox, Arizona, in 1946 with Hawks, Clift, and John Wayne. No one on the movie crew is aware that Susan is the daughter of the character Clift is playing in the movie. She has told Hawks her name is Hickey, and when Clift arrives on the set, Hawks performs the introductions:

"Miss Hickey...may I introduce Mr. Clift, our Matthew Garth?"

The spurious father and the unknown daughter shook hands, worlds and fifty years apart.

"Interesting role you've got," said Susan.

"Well, look," grinned Clift, tolerantly, "this is just a Western, you know."

"Still," she persevered, "the real Garth. He was an unusual fellow."

"Hey, Howard," whined Clift, "was Garth a real person? Is that right?"

Delicate and dangerous, Howard saunteringly rejoined them. "There are no real people," he told them. "See if they sue."

There are no real people; there are only the ones we can imagine truly. When I read Hawks's made-up words, I could hear echoes of Clifford Geertz and Colum McCann and E.L. Doctorow and every writer on my incomplete and ever-growing list.

The I's Have It

This homage to Ragtime would not be complete without mention of two related strains of fiction. In the first, a writer places a historical figure at center stage and then attempts to channel that character's voice and enter his mind. One of this strain's early avatars was the wildly popular 1934 novel I, Claudius, in which Robert Graves set out to refute the conventional view that the man who ruled the Roman Empire from 41 to 54 A.D. was a stuttering, doddering idiot. (Graves followed it a year later with Claudius the God.) Jerry Stahl took on a similar revisionist challenge in 2008 with I, Fatty, a look into the dark soul of the supposedly sunny silent-movie star Roscoe Arbuckle. Other figures from history, literature, and myth who have become titles of I, ______ novels include Hogarth, Iago and Lucifer. And then there are such masterpieces of ventriloquism as Peter Carey's True History of the Kelly Gang, Margeurite Yourcenar's Memoirs of Hadrian, and Thomas Berger's Little Big Man (whose narrator, fictional 111-year-old Jack Crabb, recounts his encounters with such historical figures as Gen. George Armstrong Custer, Wyatt Earp, and Wild Bill Hickok).

In the Epilogue to Little Big Man, Ralph Fielding Snell, the fictional character who tape-recorded Jack Crabb's reminiscences of the West, offers this caveat about their veracity: "So as I take my departure, dear reader, I leave the choice in your capable hands. Jack Crabb was either the most neglected hero in the history of this country or a liar of insane proportions." Or maybe he was both. Does it matter? This novel, like Ragtime, is distinguished not by the facts it relates, but by the truths it reveals.

The second strain is something that has come to be known as "self-insertion," which sounds like a sexual kink but is actually the increasingly common practice of writers inserting themselves, as characters with their own names, into their novels and stories. The practice – gimmick? – has proven irresistible to Ben Marcus, Jonathan Ames, David Foster Wallace, Kurt Vonnegut, Bret Easton Ellis, Douglas Coupland, Philip Roth, and Nick Tosches, among others. As the wave of postmodernism became a tsunami, this trend was probably inevitable; mercifully it's not yet universal. I can't imagine coming across a character named E.L. Doctorow in a novel by E.L. Doctorow. His imagination is too rich and too demanding to allow such a thing.

Too Much Like Work