Mentioned in:

Most Anticipated: The Great Winter 2025 Preview

It's cold, it's grey, its bleak—but winter, at the very least, brings with it a glut of anticipation-inducing books. Here you’ll find nearly 100 titles that we’re excited to cozy up with this season. Some we’ve already read in galley form; others we’re simply eager to devour based on their authors, subjects, or blurbs. We'd love for you to find your next great read among them.

The Millions will be taking a hiatus for the next few months, but we hope to see you soon.

—Sophia Stewart, editor

January

The Legend of Kumai by Shirato Sanpei, tr. Richard Rubinger (Drawn & Quarterly)

The epic 10-volume series, a touchstone of longform storytelling in manga now published in English for the first time, follows outsider Kamui in 17th-century Japan as he fights his way up from peasantry to the prized role of ninja. —Michael J. Seidlinger

The Life of Herod the Great by Zora Neale Hurston (Amistad)

In the years before her death in 1960, Hurston was at work on what she envisioned as a continuation of her 1939 novel, Moses, Man of the Mountain. Incomplete, nearly lost to fire, and now published for the first time alongside scholarship from editor Deborah G. Plant, Hurston’s final manuscript reimagines Herod, villain of the New Testament Gospel accounts, as a magnanimous and beloved leader of First Century Judea. —Jonathan Frey

Mood Machine by Liz Pelly (Atria)

When you eagerly posted your Spotify Wrapped last year, did you notice how much of what you listened to tended to sound... the same? Have you seen all those links to Bandcamp pages your musician friends keep desperately posting in the hopes that maybe, just maybe, you might give them money for their art? If so, this book is for you. —John H. Maher

My Country, Africa by Andrée Blouin (Verso)

African revolutionary Blouin recounts a radical life steeped in activism in this vital autobiography, from her beginnings in a colonial orphanage to her essential role in the continent's midcentury struggles for decolonization. —Sophia M. Stewart

The First and Last King of Haiti by Marlene L. Daut (Knopf)

Donald Trump repeatedly directs extraordinary animus towards Haiti and Haitians. This biography of Henry Christophe—the man who played a pivotal role in the Haitian Revolution—might help Americans understand why. —Claire Kirch

The Bewitched Bourgeois by Dino Buzzati, tr. Lawrence Venuti (NYRB)

This is the second story collection, and fifth book, by the absurdist-leaning midcentury Italian writer—whose primary preoccupation was war novels that blend the brutal with the fantastical—to get the NYRB treatment. May it not be the last. —JHM

Y2K by Colette Shade (Dey Street)

The recent Y2K revival mostly makes me feel old, but Shade's essay collection deftly illuminates how we got here, connecting the era's social and political upheavals to today. —SMS

Darkmotherland by Samrat Upadhyay (Penguin)

In a vast dystopian reimagining of Nepal, Upadhyay braids narratives of resistance (political, personal) and identity (individual, societal) against a backdrop of natural disaster and state violence. The first book in nearly a decade from the Whiting Award–winning author of Arresting God in Kathmandu, this is Upadhyay’s most ambitious yet. —JF

Metamorphosis by Ross Jeffery (Truborn)

From the author of I Died Too, But They Haven’t Buried Me Yet, a woman leads a double life as she loses her grip on reality by choice, wearing a mask that reflects her inner demons, as she descends into a hell designed to reveal the innermost depths of her grief-stricken psyche. —MJS

The Containment by Michelle Adams (FSG)

Legal scholar Adams charts the failure of desegregation in the American North through the story of the struggle to integrate suburban schools in Detroit, which remained almost completely segregated nearly two decades after Brown v. Board. —SMS

Death of the Author by Nnedi Okorafor (Morrow)

African Futurist Okorafor’s book-within-a-book offers interchangeable cover images, one for the story of a disabled, Black visionary in a near-present day and the other for the lead character’s speculative posthuman novel, Rusted Robots. Okorafor deftly keeps the alternating chapters and timelines in conversation with one another. —Nathalie op de Beeck

Open Socrates by Agnes Callard (Norton)

Practically everything Agnes Callard says or writes ushers in a capital-D Discourse. (Remember that profile?) If she can do the same with a study of the philosophical world’s original gadfly, culture will be better off for it. —JHM

Aflame by Pico Iyer (Riverhead)

Presumably he finds time to eat and sleep in there somewhere, but it certainly appears as if Iyer does nothing but travel and write. His latest, following 2023’s The Half Known Life, makes a case for the sublimity, and necessity, of silent reflection. —JHM

The In-Between Bookstore by Edward Underhill (Avon)

A local bookstore becomes a literal portal to the past for a trans man who returns to his hometown in search of a fresh start in Underhill's tender debut. —SMS

Good Girl by Aria Aber (Hogarth)

Aber, an accomplished poet, turns to prose with a debut novel set in the electric excess of Berlin’s bohemian nightlife scene, where a young German-born Afghan woman finds herself enthralled by an expat American novelist as her country—and, soon, her community—is enflamed by xenophobia. —JHM

The Orange Eats Creeps by Grace Krilanovich (Two Dollar Radio)

Krilanovich’s 2010 cult classic, about a runaway teen with drug-fueled ESP who searches for her missing sister across surreal highways while being chased by a killer named Dactyl, gets a much-deserved reissue. —MJS

Mona Acts Out by Mischa Berlinski (Liveright)

In the latest novel from the National Book Award finalist, a 50-something actress reevaluates her life and career when #MeToo allegations roil the off-off-Broadway Shakespearean company that has cast her in the role of Cleopatra. —SMS

Something Rotten by Andrew Lipstein (FSG)

A burnt-out couple leave New York City for what they hope will be a blissful summer in Denmark when their vacation derails after a close friend is diagnosed with a rare illness and their marriage is tested by toxic influences. —MJS

The Sun Won't Come Out Tomorrow by Kristen Martin (Bold Type)

Martin's debut is a cultural history of orphanhood in America, from the 1800s to today, interweaving personal narrative and archival research to upend the traditional "orphan narrative," from Oliver Twist to Annie. —SMS

We Do Not Part by Han Kang, tr. E. Yaewon and Paige Aniyah Morris (Hogarth)

Kang’s Nobel win last year surprised many, but the consistency of her talent certainly shouldn't now. The latest from the author of The Vegetarian—the haunting tale of a Korean woman who sets off to save her injured friend’s pet at her home in Jeju Island during a deadly snowstorm—will likely once again confront the horrors of history with clear eyes and clarion prose. —JHM

We Are Dreams in the Eternal Machine by Deni Ellis Béchard (Milkweed)

As the conversation around emerging technology skews increasingly to apocalyptic and utopian extremes, Béchard’s latest novel adopts the heterodox-to-everyone approach of embracing complexity. Here, a cadre of characters is isolated by a rogue but benevolent AI into controlled environments engineered to achieve their individual flourishing. The AI may have taken over, but it only wants to best for us. —JF

The Harder I Fight the More I Love You by Neko Case (Grand Central)

Singer-songwriter Case, a country- and folk-inflected indie rocker and sometime vocalist for the New Pornographers, takes her memoir’s title from her 2013 solo album. Followers of PNW music scene chronicles like Kathleen Hanna’s Rebel Girl and drummer Steve Moriarty’s Mia Zapata and the Gits will consider Case’s backstory a must-read. —NodB

The Loves of My Life by Edmund White (Bloomsbury)

The 85-year-old White recounts six decades of love and sex in this candid and erotic memoir, crafting a landmark work of queer history in the process. Seminal indeed. —SMS

Blob by Maggie Su (Harper)

In Su’s hilarious debut, Vi Liu is a college dropout working a job she hates, nothing really working out in her life, when she stumbles across a sentient blob that she begins to transform as her ideal, perfect man that just might resemble actor Ryan Gosling. —MJS

Sinkhole and Other Inexplicable Voids by Leyna Krow (Penguin)

Krow’s debut novel, Fire Season, traced the combustible destinies of three Northwest tricksters in the aftermath of an 1889 wildfire. In her second collection of short fiction, Krow amplifies surreal elements as she tells stories of ordinary lives. Her characters grapple with deadly viruses, climate change, and disasters of the Anthropocene’s wilderness. —NodB

Black in Blues by Imani Perry (Ecco)

The National Book Award winner—and one of today's most important thinkers—returns with a masterful meditation on the color blue and its role in Black history and culture. —SMS

Too Soon by Betty Shamieh (Avid)

The timely debut novel by Shamieh, a playwright, follows three generations of Palestinian American women as they navigate war, migration, motherhood, and creative ambition. —SMS

How to Talk About Love by Plato, tr. Armand D'Angour (Princeton UP)

With modern romance on its last legs, D'Angour revisits Plato's Symposium, mining the philosopher's masterwork for timeless, indispensable insights into love, sex, and attraction. —SMS

At Dark, I Become Loathsome by Eric LaRocca (Blackstone)

After Ashley Lutin’s wife dies, he takes the grieving process in a peculiar way, posting online, “If you're reading this, you've likely thought that the world would be a better place without you,” and proceeds to offer a strange ritual for those that respond to the line, equally grieving and lost, in need of transcendence. —MJS

February

No One Knows by Osamu Dazai, tr. Ralph McCarthy (New Directions)

A selection of stories translated in English for the first time, from across Dazai’s career, demonstrates his penchant for exploring conformity and society’s often impossible expectations of its members. —MJS

Mutual Interest by Olivia Wolfgang-Smith (Bloomsbury)

This queer love story set in post–Gilded Age New York, from the author of Glassworks (and one of my favorite Millions essays to date), explores on sex, power, and capitalism through the lives of three queer misfits. —SMS

Pure, Innocent Fun by Ira Madison III (Random House)

This podcaster and pop culture critic spoke to indie booksellers at a fall trade show I attended, regaling us with key cultural moments in the 1990s that shaped his youth in Milwaukee and being Black and gay. If the book is as clever and witty as Madison is, it's going to be a winner. —CK

Gliff by Ali Smith (Pantheon)

The Scottish author has been on the scene since 1997 but is best known today for a seasonal quartet from the late twenty-teens that began in 2016 with Autumn and ended in 2020 with Summer. Here, she takes the genre turn, setting two children and a horse loose in an authoritarian near future. —JHM

Land of Mirrors by Maria Medem, tr. Aleshia Jensen and Daniela Ortiz (D&Q)

This hypnotic graphic novel from one of Spain's most celebrated illustrators follows Antonia, the sole inhabitant of a deserted town, on a color-drenched quest to preserve the dying flower that gives her purpose. —SMS

Bibliophobia by Sarah Chihaya (Random House)

As odes to the "lifesaving power of books" proliferate amid growing literary censorship, Chihaya—a brilliant critic and writer—complicates this platitude in her revelatory memoir about living through books and the power of reading to, in the words of blurber Namwali Serpell, "wreck and redeem our lives." —SMS

Reading the Waves by Lidia Yuknavitch (Riverhead)

Yuknavitch continues the personal story she began in her 2011 memoir, The Chronology of Water. More than a decade after that book, and nearly undone by a history of trauma and the death of her daughter, Yuknavitch revisits the solace she finds in swimming (she was once an Olympic hopeful) and in her literary community. —NodB

The Dissenters by Youssef Rakha (Graywolf)

A son reevaluates the life of his Egyptian mother after her death in Rakha's novel. Recounting her sprawling life story—from her youth in 1960s Cairo to her experience of the 2011 Tahrir Square protests—a vivid portrait of faith, feminism, and contemporary Egypt emerges. —SMS

Tetra Nova by Sophia Terazawa (Deep Vellum)

Deep Vellum has a particularly keen eye for fiction in translation that borders on the unclassifiable. This debut from a poet the press has published twice, billed as the story of “an obscure Roman goddess who re-imagines herself as an assassin coming to terms with an emerging performance artist identity in the late-20th century,” seems right up that alley. —JHM

David Lynch's American Dreamscape by Mike Miley (Bloomsbury)

Miley puts David Lynch's films in conversation with literature and music, forging thrilling and unexpected connections—between Eraserhead and "The Yellow Wallpaper," Inland Empire and "mixtape aesthetics," Lynch and the work of Cormac McCarthy. Lynch devotees should run, not walk. —SMS

There's No Turning Back by Alba de Céspedes, tr. Ann Goldstein (Washington Square)

Goldstein is an indomitable translator. Without her, how would you read Ferrante? Here, she takes her pen to a work by the great Cuban-Italian writer de Céspedes, banned in the fascist Italy of the 1930s, that follows a group of female literature students living together in a Roman boarding house. —JHM

Beta Vulgaris by Margie Sarsfield (Norton)

Named for the humble beet plant and meaning, in a rough translation from the Latin, "vulgar second," Sarsfield’s surreal debut finds a seasonal harvest worker watching her boyfriend and other colleagues vanish amid “the menacing but enticing siren song of the beets.” —JHM

People From Oetimu by Felix Nesi, tr. Lara Norgaard (Archipelago)

The center of Nesi’s wide-ranging debut novel is a police station on the border between East and West Timor, where a group of men have gathered to watch the final of the 1998 World Cup while a political insurgency stirs without. Nesi, in English translation here for the first time, circles this moment broadly, reaching back to the various colonialist projects that have shaped Timor and the lives of his characters. —JF

Brother Brontë by Fernando A. Flores (MCD)

This surreal tale, set in a 2038 dystopian Texas is a celebration of resistance to authoritarianism, a mash-up of Olivia Butler, Ray Bradbury, and John Steinbeck. —CK

Alligator Tears by Edgar Gomez (Crown)

The High-Risk Homosexual author returns with a comic memoir-in-essays about fighting for survival in the Sunshine State, exploring his struggle with poverty through the lens of his queer, Latinx identity. —SMS

Theory & Practice by Michelle De Kretser (Catapult)

This lightly autofictional novel—De Krester's best yet, and one of my favorite books of this year—centers on a grad student's intellectual awakening, messy romantic entanglements, and fraught relationship with her mother as she minds the gap between studying feminist theory and living a feminist life. —SMS

The Lamb by Lucy Rose (Harper)

Rose’s cautionary and caustic folk tale is about a mother and daughter who live alone in the forest, quiet and tranquil except for the visitors the mother brings home, whom she calls “strays,” wining and dining them until they feast upon the bodies. —MJS

Disposable by Sarah Jones (Avid)

Jones, a senior writer for New York magazine, gives a voice to America's most vulnerable citizens, who were deeply and disproportionately harmed by the pandemic—a catastrophe that exposed the nation's disregard, if not outright contempt, for its underclass. —SMS

No Fault by Haley Mlotek (Viking)

Written in the aftermath of the author's divorce from the man she had been with for 12 years, this "Memoir of Romance and Divorce," per its subtitle, is a wise and distinctly modern accounting of the end of a marriage, and what it means on a personal, social, and literary level. —SMS

Enemy Feminisms by Sophie Lewis (Haymarket)

Lewis, one of the most interesting and provocative scholars working today, looks at certain malignant strains of feminism that have done more harm than good in her latest book. In the process, she probes the complexities of gender equality and offers an alternative vision of a feminist future. —SMS

Lion by Sonya Walger (NYRB)

Walger—an successful actor perhaps best known for her turn as Penny Widmore on Lost—debuts with a remarkably deft autobiographical novel (published by NYRB no less!) about her relationship with her complicated, charismatic Argentinian father. —SMS

The Voices of Adriana by Elvira Navarro, tr. Christina MacSweeney (Two Lines)

A Spanish writer and philosophy scholar grieves her mother and cares for her sick father in Navarro's innovative, metafictional novel. —SMS

Autotheories ed. Alex Brostoff and Vilashini Cooppan (MIT)

Theory wonks will love this rigorous and surprisingly playful survey of the genre of autotheory—which straddles autobiography and critical theory—with contributions from Judith Butler, Jamieson Webster, and more.

Fagin the Thief by Allison Epstein (Doubleday)

I enjoy retellings of classic novels by writers who turn the spotlight on interesting minor characters. This is an excursion into the world of Charles Dickens, told from the perspective iconic thief from Oliver Twist. —CK

Crush by Ada Calhoun (Viking)

Calhoun—the masterful memoirist behind the excellent Also A Poet—makes her first foray into fiction with a debut novel about marriage, sex, heartbreak, all-consuming desire. —SMS

Show Don't Tell by Curtis Sittenfeld (Random House)

Sittenfeld's observations in her writing are always clever, and this second collection of short fiction includes a tale about the main character in Prep, who visits her boarding school decades later for an alumni reunion. —CK

Right-Wing Woman by Andrea Dworkin (Picador)

One in a trio of Dworkin titles being reissued by Picador, this 1983 meditation on women and American conservatism strikes a troublingly resonant chord in the shadow of the recent election, which saw 45% of women vote for Trump. —SMS

The Talent by Daniel D'Addario (Scout)

If your favorite season is awards, the debut novel from D'Addario, chief correspondent at Variety, weaves an awards-season yarn centering on five stars competing for the Best Actress statue at the Oscars. If you know who Paloma Diamond is, you'll love this. —SMS

Death Takes Me by Cristina Rivera Garza, tr. Sarah Booker and Robin Myers (Hogarth)

The Pulitzer winner’s latest is about an eponymously named professor who discovers the body of a mutilated man with a bizarre poem left with the body, becoming entwined in the subsequent investigation as more bodies are found. —MJS

The Strange Case of Jane O. by Karen Thompson Walker (Random House)

Jane goes missing after a sudden a debilitating and dreadful wave of symptoms that include hallucinations, amnesia, and premonitions, calling into question the foundations of her life and reality, motherhood and buried trauma. —MJS

Song So Wild and Blue by Paul Lisicky (HarperOne)

If it weren’t Joni Mitchell’s world with all of us just living in it, one might be tempted to say the octagenarian master songstress is having a moment: this memoir of falling for the blue beauty of Mitchell’s work follows two other inventive books about her life and legacy: Ann Powers's Traveling and Henry Alford's I Dream of Joni. —JHM

Mornings Without Mii by Mayumi Inaba, tr. Ginny Tapley (FSG)

A woman writer meditates on solitude, art, and independence alongside her beloved cat in Inaba's modern classic—a book so squarely up my alley I'm somehow embarrassed. —SMS

True Failure by Alex Higley (Coffee House)

When Ben loses his job, he decides to pretend to go to work while instead auditioning for Big Shot, a popular reality TV show that he believes might be a launchpad for his future successes. —MJS

March

Woodworking by Emily St. James (Crooked Reads)

Those of us who have been reading St. James since the A.V. Club days may be surprised to see this marvelous critic's first novel—in this case, about a trans high school teacher befriending one of her students, the only fellow trans woman she’s ever met—but all the more excited for it. —JHM

Optional Practical Training by Shubha Sunder (Graywolf)

Told as a series of conversations, Sunder’s debut novel follows its recently graduated Indian protagonist in 2006 Cambridge, Mass., as she sees out her student visa teaching in a private high school and contriving to find her way between worlds that cannot seem to comprehend her. Quietly subversive, this is an immigration narrative to undermine the various reductionist immigration narratives of our moment. —JF

Love, Queenie by Mayukh Sen (Norton)

Merle Oberon, one of Hollywood's first South Asian movie stars, gets her due in this engrossing biography, which masterfully explores Oberon's painful upbringing, complicated racial identity, and much more. —SMS

The Age of Choice by Sophia Rosenfeld (Princeton UP)

At a time when we are awash with options—indeed, drowning in them—Rosenfeld's analysis of how our modingn idea of "freedom" became bound up in the idea of personal choice feels especially timely, touching on everything from politics to romance. —SMS

Sucker Punch by Scaachi Koul (St. Martin's)

One of the internet's funniest writers follows up One Day We'll All Be Dead and None of This Will Matter with a sharp and candid collection of essays that sees her life go into a tailspin during the pandemic, forcing her to reevaluate her beliefs about love, marriage, and what's really worth fighting for. —SMS

The Mysterious Disappearance of the Marquise of Loria by José Donoso, tr. Megan McDowell (New Directions)

The ever-excellent McDowell translates yet another work by the influential Chilean author for New Directions, proving once again that Donoso had a knack for titles: this one follows up 2024’s behemoth The Obscene Bird of Night. —JHM

Remember This by Anthony Giardina (FSG)

On its face, it’s another book about a writer living in Brooklyn. A layer deeper, it’s a book about fathers and daughters, occupations and vocations, ethos and pathos, failure and success. —JHM

Ultramarine by Mariette Navarro (Deep Vellum)

In this metaphysical and lyrical tale, a captain known for sticking to protocol begins losing control not only of her crew and ship but also her own mind. —MJS

We Tell Ourselves Stories by Alissa Wilkinson (Liveright)

Amid a spate of new books about Joan Didion published since her death in 2021, this entry by Wilkinson (one of my favorite critics working today) stands out for its approach, which centers Hollywood—and its meaning-making apparatus—as an essential key to understanding Didion's life and work. —SMS

Seven Social Movements that Changed America by Linda Gordon (Norton)

This book—by a truly renowned historian—about the power that ordinary citizens can wield when they organize to make their community a better place for all could not come at a better time. —CK

Mothers and Other Fictional Characters by Nicole Graev Lipson (Chronicle Prism)

Lipson reconsiders the narratives of womanhood that constrain our lives and imaginations, mining the canon for alternative visions of desire, motherhood, and more—from Kate Chopin and Gwendolyn Brooks to Philip Roth and Shakespeare—to forge a new story for her life. —SMS

Goddess Complex by Sanjena Sathian (Penguin)

Doppelgängers have been done to death, but Sathian's examination of Millennial womanhood—part biting satire, part twisty thriller—breathes new life into the trope while probing the modern realities of procreation, pregnancy, and parenting. —SMS

Stag Dance by Torrey Peters (Random House)

The author of Detransition, Baby offers four tales for the price of one: a novel and three stories that promise to put gender in the crosshairs with as sharp a style and swagger as Peters’ beloved latest. The novel even has crossdressing lumberjacks. —JHM

On Breathing by Jamieson Webster (Catapult)

Webster, a practicing psychoanalyst and a brilliant writer to boot, explores that most basic human function—breathing—to address questions of care and interdependence in an age of catastrophe. —SMS

Unusual Fragments: Japanese Stories (Two Lines)

The stories of Unusual Fragments, including work by Yoshida Tomoko, Nobuko Takai, and other seldom translated writers from the same ranks as Abe and Dazai, comb through themes like alienation and loneliness, from a storm chaser entering the eye of a storm to a medical student observing a body as it is contorted into increasingly violent positions. —MJS

The Antidote by Karen Russell (Knopf)

Russell has quipped that this Dust Bowl story of uncanny happenings in Nebraska is the “drylandia” to her 2011 Florida novel, Swamplandia! In this suspenseful account, a woman working as a so-called prairie witch serves as a storage vault for her townspeople’s most troubled memories of migration and Indigenous genocide. With a murderer on the loose, a corrupt sheriff handling the investigation, and a Black New Deal photographer passing through to document Americana, the witch loses her memory and supernatural events parallel the area’s lethal dust storms. —NodB

On the Clock by Claire Baglin, tr. Jordan Stump (New Directions)

Baglin's bildungsroman, translated from the French, probes the indignities of poverty and service work from the vantage point of its 20-year-old narrator, who works at a fast-food joint and recalls memories of her working-class upbringing. —SMS

Motherdom by Alex Bollen (Verso)

Parenting is difficult enough without dealing with myths of what it means to be a good mother. I who often felt like a failure as a mother appreciate Bollen's focus on a more realistic approach to parenting. —CK

The Magic Books by Anne Lawrence-Mathers (Yale UP)

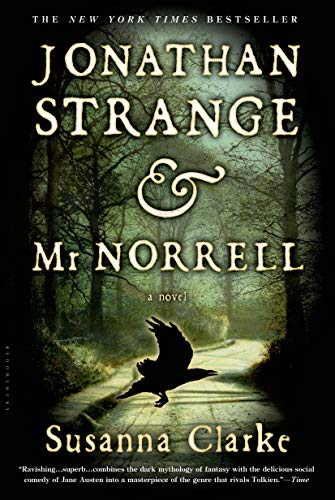

For that friend who wants to concoct the alchemical elixir of life, or the person who cannot quit Susanna Clark’s Jonathan Strange and Mr. Norrell, Lawrence-Mathers collects 20 illuminated medieval manuscripts devoted to magical enterprise. Her compendium includes European volumes on astronomy, magical training, and the imagined intersection between science and the supernatural. —NodB

Theft by Abdulrazak Gurnah (Riverhead)

The first novel by the Tanzanian-British Nobel laureate since his surprise win in 2021 is a story of class, seismic cultural change, and three young people in a small Tanzania town, caught up in both as their lives dramatically intertwine. —JHM

Twelve Stories by American Women, ed. Arielle Zibrak (Penguin Classics)

Zibrak, author of a delicious volume on guilty pleasures (and a great essay here at The Millions), curates a dozen short stories by women writers who have long been left out of American literary canon—most of them women of color—from Frances Ellen Watkins Harper to Zitkala-Ša. —SMS

I'll Love You Forever by Giaae Kwon (Holt)

K-pop’s sky-high place in the fandom landscape made a serious critical assessment inevitable. This one blends cultural criticism with memoir, using major artists and their careers as a lens through which to view the contemporary Korean sociocultural landscape writ large. —JHM

The Buffalo Hunter Hunter by Stephen Graham Jones (Saga)

Jones, the acclaimed author of The Only Good Indians and the Indian Lake Trilogy, offers a unique tale of historical horror, a revenge tale about a vampire descending upon the Blackfeet reservation and the manifold of carnage in their midst. —MJS

True Mistakes by Lena Moses-Schmitt (University of Arkansas Press)

Full disclosure: Lena is my friend. But part of why I wanted to be her friend in the first place is because she is a brilliant poet. Selected by Patricia Smith as a finalist for the Miller Williams Poetry Prize, and blurbed by the great Heather Christle and Elisa Gabbert, this debut collection seeks to turn "mistakes" into sites of possibility. —SMS

Perfection by Vicenzo Latronico, tr. Sophie Hughes (NYRB)

Anna and Tom are expats living in Berlin enjoying their freedom as digital nomads, cultivating their passion for capturing perfect images, but after both friends and time itself moves on, their own pocket of creative freedom turns boredom, their life trajectories cast in doubt. —MJS

Guatemalan Rhapsody by Jared Lemus (Ecco)

Jemus's debut story collection paint a composite portrait of the people who call Guatemala home—and those who have left it behind—with a cast of characters that includes a medicine man, a custodian at an underfunded college, wannabe tattoo artists, four orphaned brothers, and many more.

Pacific Circuit by Alexis Madrigal (MCD)

The Oakland, Calif.–based contributing writer for the Atlantic digs deep into the recent history of a city long under-appreciated and under-served that has undergone head-turning changes throughout the rise of Silicon Valley. —JHM

Barbara by Joni Murphy (Astra)

Described as "Oppenheimer by way of Lucia Berlin," Murphy's character study follows the titular starlet as she navigates the twinned convulsions of Hollywood and history in the Atomic Age.

Sister Sinner by Claire Hoffman (FSG)

This biography of the fascinating Aimee Semple McPherson, America's most famous evangelist, takes religion, fame, and power as its subjects alongside McPherson, whose life was suffused with mystery and scandal. —SMS

Trauma Plot by Jamie Hood (Pantheon)

In this bold and layered memoir, Hood confronts three decades of sexual violence and searches for truth among the wreckage. Kate Zambreno calls Trauma Plot the work of "an American Annie Ernaux." —SMS

Hey You Assholes by Kyle Seibel (Clash)

Seibel’s debut story collection ranges widely from the down-and-out to the downright bizarre as he examines with heart and empathy the strife and struggle of his characters. —MJS

James Baldwin by Magdalena J. Zaborowska (Yale UP)

Zaborowska examines Baldwin's unpublished papers and his material legacy (e.g. his home in France) to probe about the great writer's life and work, as well as the emergence of the "Black queer humanism" that Baldwin espoused. —CK

Stop Me If You've Heard This One by Kristen Arnett (Riverhead)

Arnett is always brilliant and this novel about the relationship between Cherry, a professional clown, and her magician mentor, "Margot the Magnificent," provides a fascinating glimpse of the unconventional lives of performance artists. —CK

Paradise Logic by Sophie Kemp (S&S)

The deal announcement describes the ever-punchy writer’s debut novel with an infinitely appealing appellation: “debauched picaresque.” If that’s not enough to draw you in, the truly unhinged cover should be. —JHM

[millions_email]

A Year in Reading: 2024

Welcome to the 20th (!) installment of The Millions' annual Year in Reading series, which gathers together some of today's most exciting writers and thinkers to share the books that shaped their year. YIR is not a collection of yearend best-of lists; think of it, perhaps, as an assemblage of annotated bibliographies. We've invited contributors to reflect on the books they read this year—an intentionally vague prompt—and encouraged them to approach the assignment however they choose.

In writing about our reading lives, as YIR contributors are asked to do, we inevitably write about our personal lives, our inner lives. This year, a number of contributors read their way through profound grief and serious illness, through new parenthood and cross-country moves. Some found escape in frothy romances, mooring in works of theology, comfort in ancient epic poetry. More than one turned to the wisdom of Ursula K. Le Guin. Many describe a book finding them just when they needed it.

Interpretations of the assignment were wonderfully varied. One contributor, a music critic, considered the musical analogs to the books she read, while another mapped her reads from this year onto constellations. Most people's reading was guided purely by pleasure, or else a desire to better understand events unfolding in their lives or larger the world. Yet others centered their reading around a certain sense of duty: this year one contributor committed to finishing the six Philip Roth novels he had yet to read, an undertaking that he likens to “eating a six-pack of paper towels.” (Lucky for us, he included in his essay his final ranking of Roth's oeuvre.)

The books that populate these essays range widely, though the most commonly noted title this year was Tony Tulathimutte’s story collection Rejection. The work of newly minted National Book Award winner Percival Everett, particularly his acclaimed novel James, was also widely read and written about. And as the genocide of Palestinians in Gaza enters its second year, many contributors sought out Isabella Hammad’s searing, clear-eyed essay Recognizing the Stranger.

Like so many endeavors in our chronically under-resourced literary community, Year in Reading is a labor of love. The Millions is a one-person editorial operation (with an invaluable assist from SEO maven Dani Fishman), and producing YIR—and witnessing the joy it brings contributors and readers alike—has been the highlight of my tenure as editor. I’m profoundly grateful for the generosity of this year’s contributors, whose names and entries will be revealed below over the next three weeks, concluding on Wednesday, December 18. Be sure to subscribe to The Millions’ free newsletter to get the week’s entries sent straight to your inbox each Friday.

—Sophia Stewart, editor

Becca Rothfeld, author of All Things Are Too Small

Carvell Wallace, author of Another Word for Love

Charlotte Shane, author of An Honest Woman

Brianna Di Monda, writer and editor

Nell Irvin Painter, author of I Just Keep Talking

Carrie Courogen, author of Miss May Does Not Exist

Ayşegül Savaş, author of The Anthropologists

Zachary Issenberg, writer

Tony Tulathimutte, author of Rejection

Ann Powers, author of Traveling: On the Path of Joni Mitchell

Lidia Yuknavitch, author of Reading the Waves

Nicholas Russell, writer and critic

Daniel Saldaña París, author of Planes Flying Over a Monster

Lili Anolik, author of Didion and Babitz

Deborah Ghim, editor

Emily Witt, author of Health and Safety

Nathan Thrall, author of A Day in the Life of Abed Salama

Lena Moses-Schmitt, author of True Mistakes

Jeremy Gordon, author of See Friendship

John Lee Clark, author of Touch the Future

Ellen Wayland-Smith, author of The Science of Last Things

Edwin Frank, publisher and author of Stranger Than Fiction

Sophia Stewart, editor of The Millions

A Year in Reading Archives: 2023, 2022, 2021, 2020, 2019, 2018, 2017, 2016, 2015, 2014, 2013, 2011, 2010, 2009, 2008, 2007, 2006, 2005

Tuesday New Release Day: Starring Popkey, Hass, Reid, Palahniuk, and More

Here’s a quick look at some notable books—new titles from the likes of Miranda Popkey, Robert Hass, Kiley Reid, Chuck Palahniuk, and more—that are publishing this week.

Want to learn more about upcoming titles? Then go read our most recent book preview. Want to help The Millions keep churning out great books coverage? Then sign up to be a member today.

Topics of Conversation by Miranda Popkey

Here's what Publishers Weekly had to say about Topics of Conversation: "The women in Popkey’s astute debut bristle with wanting. Readers meet the unnamed narrator in Italy, 'twenty-one and daffy with sensation,' where she is working as a nanny for a well-off friend’s younger brothers while her friend leaves her behind in favor of Greek tourists she’s met on the beach. In her third week, she has a late-night conversation with her friend’s mother, Artemisia, an Argentinean psychoanalyst, about their paralleled romantic histories with much older men, both their former professors. These conversations about power, responsibility, and desire, often as they manifest in relationships with men, provide the backbone for the subsequent sections of the novel, which follow the narrator through breakups with friends, with lovers, and motherhood. As the years progress, the narrator’s hyperawareness and cheeky playfulness when it comes to her narrative as something she owns, grows as well. At a new moms meetup in Fresno 14 years after that night in Italy, the narrator asks the rest of the moms to share 'how we got here.' The story she herself shares is an echo of the one she told Artemisia, but better, the details burnished and editorialized. Popkey’s prose is overly controlled, but this is nonetheless a searing and cleverly constructed novel and a fine indication of what’s to come from this promising author."

Summer Snow by Robert Hass

Here's what Publishers Weekly had to say about Summer Snow: "In this ruminative, endlessly clever book, Pulitzer Prize–winner Hass (The Apple Trees at Olema) turns his eye toward nature, love, and even drone strikes, as, when chronicling a visit to a Las Vegas Air Force base for a protest, he juxtaposes the specter of commerce at a nearby casino with headlines detailing drone-related deaths in the Middle East. Though death may be the prevailing theme, these poems are far from dirges, as images of his Northern California environs shimmer with life: 'you can almost hear the earth sigh/ As it sucks up the rain.' Hass experiments with form, vacillating between long and short lines, stanzas and long unbroken blocks of verse. His language is lofty but accessible, as in 'The Archaeology of Plenty,' a loose, associative riff about finding meaning in a callous and capricious world, in which the poet argues for poetry as a cure for existential dread: 'reach into your heavy waking,/ The metaphysical nausea that being in your life,/ With its bearing and its strife, its stiffs,/ Its stuff, seems to have produced in you,/ Reduced you to, and make something with a pleasing,/ Or teasing, ring to it.' Hass is a rarity, a poet’s poet and a reader’s poet who, with this newest endeavor, bestows a precious gift to his audience."

Such a Fun Age by Kiley Reid

Here's what Publishers Weekly had to say about Such a Fun Age: "In her debut, Reid crafts a nuanced portrait of a young black woman struggling to define herself apart from the white people in her life who are all too ready to speak and act on her behalf. Emira Tucker knows that the one thing she’s unequivocally good at is taking care of children, specifically the two young daughters, Briar and Catherine, of her part-time employer, Alix Chamberlain. However, about to turn 26 and lose her parents’ health insurance, and while watching her friends snatch up serious boyfriends and enviable promotions, Temple grad Emira starts to feel ashamed about 'still' babysitting. This humiliation is stoked after she’s harassed by security personnel at an upscale Philadelphia grocery store where she’d taken three-year-old Briar. Emira later develops a romantic relationship with Kelley, the young white man who captured cellphone video of the altercation, only to discover that Kelley and Alix have a shared and uncomfortable past, one that traps Emira in the middle despite assertions that everyone has her best interests at heart. Reid excels at depicting subtle variations and manifestations of self-doubt, and astutely illustrates how, when coupled with unrecognized white privilege, this emotional and professional insecurity can result in unintended—as well as willfully unseen—consequences. This is an impressive, memorable first outing."

Qualityland by Marc-Uwe Kling (translated by Jamie Searle Romanelli)

Here's what Publishers Weekly had to say about Qualityland: "The latest from Kling (The Kangaroo Chronicles), already in production at HBO, is a hilarious romp through an absurd hypercapitalist dystopia. After the third 'crisis of the century' in a decade, a country is renamed QualityLand. There, each person is named after their parents’ professions, has a social media feed specially created by a corporation, and is assigned a level from 1 to 100, which dictates what partner someone can match with, what job someone can have, and so on. Peter Jobless is a low-level metal recycling scrapper who, one day, receives a delivery from TheShop that he didn’t order—not unusual in itself, as TheShop anticipates all desires (its motto is 'We know what you want')—but more importantly, that he doesn’t want. Aided by the defective robots living under his shop that he saved from the scrapper, Peter embarks on a journey to return his unwanted delivery. Peter’s quest unfolds against the backdrop of a presidential election, where voters can choose between a maximally intelligent, socialist-minded robot programmed for objectivity, and a celebrity right-wing chef, prone to contradicting himself in the same sentence. No need to guess who’s leading the polls. Sharp and biting, the most implausible aspect of Kling’s novel is the relative note of optimism that ends it. This is spot-on satire."

Consider This by Chuck Palahniuk

Here's what Publishers Weekly had to say about Consider This: "Palahniuk (Adjustment Day) delivers a fine book on writing, full of advice and anecdotes garnered from his career as a novelist, that will help both those aspiring to write bestsellers and those hoping to write from the heart. His practical tips range from the importance of surprising one’s readers to the need to torment one’s characters. He concludes the book’s nuts-and-bolts component with a troubleshooting chart (he asks those whose beginnings don’t hook readers, 'Do you begin with a thesis sentence that summarizes, or do you begin by raising a compelling question or possibility?'). Palahniuk also writes about his own life, in recurrent 'Postcards from the Tour' sections on the joys and trials of being a famous author (the latter including an incident when a book-signing attendee, angered that Palahniuk refused to sign a Don DeLillo novel, attacked him with a tube full of mice). The book finally rises to a moving emotional crescendo, in a final chapter that shares moments of serendipity from Palahniuk’s time on the road. Reminiscent of Stephen King’s On Writing in never failing to entertain while imparting wisdom, this is an indispensable resource for writers."

Writing During Your Daily Commute: The Story of Fiona Mozley’s ‘Elmet’

Fiona Mozley, the author of Man Booker shortlisted and Dylan Thomas Prize longlisted Elmet, wrote her debut novel while travelling between Peckham, in South London, and her nine to six job in Central London. She missed the landscape of northern England, which is where she grew up and where Elmet is set. Jotting down notes on her smartphone and laptop, she attempted to evoke this landscape during her daily commute, allowing a temporary respite from the daily grind.

Though we seldom see people writing on trains, many commuters read or browse aimlessly on their smartphones. Emily St. John Mandel, staff writer of The Millions, spoke of her subway writing habit in "Writing on Trains." “With a combined total of six hours spent on a subway a week, it felt like extra time,” she says. Mandel sought out other writers who wrote on trains, including memoirist Julie Klam and novelist Joe Wallace. Klam appreciated the need to beat the clock and get down thoughts before her station, as opposed to the long hours she’d spend writing at home on her Mac.

Many authors cite smartphones and the Internet as hindrances to creative writing. When Nobel Prize-winner Kazuo Ishiguro wrote The Remains of the Day, he did nothing but write from nine am to 10.30 pm for four weeks, during which time he wouldn’t go near his phone or email. In his popular book On Writing, Stephen King suggested writers eliminate distraction; “There should be no telephone in your writing room,” he wrote, “certainly no TV or video games for you to fool around with.”

Analogue writing setups of the past would offer fewer opportunities for distraction; the view from the open window and the kettle perhaps being the most enticing. Joyce Carol Oates, Jhumpa Lahiri, and Amy Tan still write their first drafts longhand, while Cormac McCarthy still types his manuscripts on an Olivetti Lettera 32.

When used productively, modern day technology can be transformed from a creativity-killing distraction to a convenient tool to note down those epiphanies or observations that would otherwise be forgotten.

If Werner Herzog’s documentary Lo and Behold: Reveries of the Connected World holds any truth, modern technologies will soon become more integrated into our daily life. “You could essentially in the not too distant future, tweet thoughts,” Marcel Just, the D.O. Hebb University Professor of Psychology at Carnegie Mellon University tells Herzog. “So not type your little tweet, but think it, press a button, and all of your followers could potentially read it.” One day we might be able to transcribe words directly from our minds onto the page. The importance of writing, in the traditional sense, is evolving. Perhaps the romantic notion of putting a pen to paper might start to wane, as we see the value of being able to pluck ideas straight from the unconscious mind.

Unlike many in her field, Fiona Mozley embraced the convenience of technology. “When I started writing Elmet I used a Chromebook–one of those cheap laptops made by Google, which require the use of online apps,” she tells me. "That meant that the only word-processor available to me was Google Docs. That made it very easy to write on either my laptop or my phone as it was all the same document.”

"I find variety to be a real aid to writing,” she continues. "If I’m in a rut, I find the best remedy is moving to another location or altering my media. So if I’ve been writing for a while on my computer and I get stuck, I’ll go and pick up a pen and paper, or vice versa. The phone writing is really just tied to that overall process."

The author wrote the first few paragraphs of her debut novel in spring 2013. She had just visited her parents for the weekend in West Yorkshire, a region previously known as Elmet, a Celtic Kingdom, between the fifth and seventh centuries. It was early on a Monday morning and she was returning to London by train. The importance of trains and train tracks in Elmet is emphasized even in the opening paragraphs:

I cast no shadow. Smoke rests behind me and daylight is stifled. I count railroad ties and the numbers rush. I count rivets and bolts. I walk north. My first two steps are slow, languid. I am unsure of the direction but in that initial choice I am pinned. I have passed through the turnstile and the gate is locked.

I still smell embers. The charred outline of a sinuous wreck. I hear the voices again: the men, and the girl. The rage. The fear. The resolve. Then those ruinous vibrations coursing through wood. And the lick of flames. The hot, dry spit. The sister with blood on her skin and that land put to waste. I keep to the railways track. I hear an engine far off in the distance and duck behind a hawthorn.

“The novel is all about isolation and marginalization, and being invisible in plain sight,” explains Mozley, "so it’s important that there are the trains running from London to Edinburgh just meters away from the little house in the copse, but none of the people on those trains knows anything about the lives being led there.”

While writing the early sections of her first draft, Mozley was working for a travel company in Central London and would jot down ideas on her smartphone during her journeys to and from work. Mozley says:

the sentences and paragraphs I wrote on my phone during my commute were very useful for keeping up the momentum. Sometimes when you’re writing–particularly if you’re working full time–you can have periods of writing nothing at all. Even if I found myself unable to write full sections, jotting ideas down on my phone meant that I felt a constant sense of progression.

Later in the writing process, Mozley got a MacBook and started using the popular writing app Scrivener. “It's designed specifically for long writing projects, whether they’re novels or PhDs,” she says, "I find it to be a useful way of organizing chapters, drafts and research. There is an accompanying app for phones called Scrivo, which I also have. However, I don’t write much on my phone anymore because I don’t have a daily commute.”

[millions_ad]

Despite its contemporary context, reading Elmet, one cannot fail but notice that otherworldly quality. Writing the novel was a means of escapism for Mozley, who was not particularly content living in London. She elaborates:

London is a wonderful city, but it is a very difficult place to live unless you have an incredibly high salary or you come from a rich background. I have friends from university who still live there, who will never be able to afford a flat or house that they don’t share with several others. When I lived in London, there were five of us sharing a house and we didn’t have a communal living area because we’d had to turn it into an extra bedroom. For a while I shared a bedroom with a friend to keep the costs down. This kind of thing is typical, and while you could say that it’s normal or acceptable when you’re straight out of university, this is the kind of situation that my friends will be in for the foreseeable future, into their forties or even beyond. These are people with degrees from the University of Cambridge, and people who have good jobs - they’re just not lawyers or bankers. I left London a few years ago and returned to Yorkshire, where I have a much better quality of life. It would be a shame for London, however, if all the writers and artists are forced out. With Elmet, I wanted to experiment with the idea of a rent strike. I wanted to toy with the idea of all renters getting together and refusing to pay their landlords. They all just decide to live in their houses for free.

As a university graduate with no formal qualification in creative writing, and without external incentives or a deadline, the writing of Elmet came from within. It was something to distract from Mozley’s daily commute and financial hardships. She initially wrote with no long-term goals of publication:

I really had no idea what I was going to do with my life, so I wrote Elmet in order to have something outside of myself to think about. I guess you could call it "writing as therapy," but it ended up being much more public. The otherworldly quality was always deliberate. Although it’s a contemporary novel, some of its major concerns are the thrall of history, the weight of the past, and the ways in which those things inform contemporary ways of life.

That deliberate otherworldly quality is effective in that we can imagine what lies beyond the train tracks and the fields that once belonged to the Celtic Kingdom of Elmet; and we can for a moment feel what the narrator Daniel sees and feels. Flexibility regarding the process enabled the author to record her astute observations and ideas with whatever she had to hand, as she felt them. As a consequence, the fictional Elmet feels like a world fresh from the unconscious mind.

While Elmet was still a work in progress, Mozley took on a role at a literary agency, where she realized that books are written by people not too different from herself. “In a way, I think I had always felt so removed from the sorts of people who become professional writers that it almost seemed like a fantasy profession,” she explains, "like ‘sorcerer’ or ‘superhero,' not something that people actually did." After working at the agency, however, writing professionally seemed a more attainable, realistic goal. Now writing with readers in mind, Mozley thought about what she wanted to convey to readers with Elmet:

I like fiction that provokes a sensory response. I wanted to address a number of issues in Elmet, and I would like to make people think, but primarily I want to make people feel. I’m fascinated by the idea that you can write words on a page that someone else goes on to read, and then that person might laugh out loud, or sweat with anticipation, or their breathing might quicken. I love the idea that fiction can have a physical response.

Mozley’s taste in literature is eclectic, to say the least. Her favourite opening to a novel is found in A Passage to India by E. M. Forster, while one of her favorite endings is in Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep by Philip K. Dick. “I also read a lot of medieval literature, which unfortunately a lot of people find to be quite inaccessible,” she says. “I suppose Sir Gawain and the Greene Knight might be a good place to start because there are lots of modern editions. It’s not my favorite, though. That would probably be a short Middle English narrative called Cheuelere Assigne, which contains bestiality, swan transformations, and family drama.”

Upon leaving the literary agency, Mozley returned to her hometown of York, where she combined working part-time in a book shop with a doctorate in Medieval Studies.

With this new found confidence, a willingness to write using everything she had at hand at every opportune moment, and the tone imparted to her by the historical documents she worked with during her PhD, Mozley brought us Elmet—a lyrical novel that speaks simultaneously of a country for which I have nostalgia as an expatriate, and a place that seems to belong to the realm of dreams. John, described as a giant, has built a house with his own hands in an isolated wood set in the rugged landscape of rural Yorkshire. He earns money through underground fights, which he seldom loses. He protects his children, the narrator Daniel and his elder sister Cathy, from the real world, which at times seems cruel and unjust. Together they roll cigarettes, hunt for their food—tend to the house as their father goes out for days on end. As readers, we come to realize that their ancient way of life is threatened by the land ownership laws of modernity. And all of this takes place beyond the rail tracks, across the fields, in a place to which you or I will unlikely ever venture.

Fiona Mozley is currently halfway through her second novel. “I’m not saying much,” she says, “but I will say that it is very different from Elmet!”

A Writer’s Toolbox

1.

I pulled the heavy red book down from my dad’s bookshelf. Bryan A. Garner’s A Dictionary of Modern American Usage, its cover announced. “David Foster Wallace said it’s the only usage guide he ever consulted,” my dad said, a note of pride in his voice as if he and DFW had been old buddies. “I got it on sale at The Strand.”

“Huh,” I said and sat down, opening the tome on my lap to the word “eventuate,” the subject of a controversial debate with a coworker at my day job. The entry was short and snarky:

Eventuate is ‘an elaborate journalistic word that can usually be replaced by a simpler word to advantage.’ George P. Krapp, A Comprehensive Guide to Good English (1927).

Then came several examples of its misuse, explanations of what was wrong about it, and suggestions for words should have been used in it place (e.g., “happened,” “occurred,” “took place”). This comprehensive lesson perfectly resolved my confusion, since I had misconstrued the meaning of “eventuate” as something along the lines of “would eventually lead to.”

“This is terrific!” I told my dad. “Usually when I have a usage question at work, I just Google the question—like further vs. farther—and read the first few entries that pop up.”

“See, that’s the trouble with the Internet,” he scoffed, single-handedly dismissing an entire global digital stratosphere. “The demise of authoritative references.”

It was nice to have such a complete and well-researched reference on language usage right here at my fingertips. I immediately looked up several more entries, and started chuckling and reading them aloud. “Hey, listen to this, about ‘insofar as:’ ‘the dangers range from mere feebleness or wordiness, through pleonasm or confusion of grammar.’ Zing!”

“Keep the Garner’s, then,” my dad said with a smile. “I never use it.”

Tickled, I hugged my newest diction and style guide to my chest. What a great new writer’s tool I didn’t even know that I needed. This got me thinking about my other writers’ tools. What are the books that every writer should have handy? My other go-to writing books are not necessarily manuals of mechanics, but instead are resources that provide inspiration, moral support, models of good writing, and above all, comfort.

2.

When I was 18, taking expository writing in my first semester of college, my professor, Kevin DiPirro, assigned Writing Down the Bones: Freeing the Writer Within by Natalie Goldberg. It was an optional text, so while he assigned us to read certain chapters concurrently with our other assignments, we never once discussed the content of the book in class. Instead, we wrote expository essays trying to frame rhetorical situations, analyze evidence, and make well-researched arguments. But my teacher-student relationship with Natalie Goldberg started that year, and for that, I’ll always be grateful to Kevin.

One afternoon, in a darkened corner of the library, I cracked open Writing Down the Bones. What’s this all about? I wondered. Natalie’s words spoke aloud to me, like a calm teacher, echoing in my mind:

Writing As Practice

This is the practice school of writing… You practice whether you want to or not. You don’t wait around for inspiration and a deep desire to run. It’ll never happen, especially if you are out of shape and have been avoiding it. But if you run regularly, you train your mind to cut through or ignore your resistance… Sit down with the least expectation of yourself; say, ‘I am free to write the worst junk in the world.’ You have to give yourself the space to write a lot without a destination… My rule is to finish a notebook a month. Simply fill it. That is the practice.

Then, at the end of the chapter:

Think of writing practice as loving arms you come to illogically and incoherently. It’s our wild forest where we gather energy before going to prune our garden, with our fine books and novels. It’s a continual practice.

Sit down right now. Give me this moment. Write whatever’s running through you. You might start with this moment and end up writing about the gardenia you wore at your wedding seven years ago. That’s fine. Don’t try to control it. Stay present with whatever comes up, and keep your hand moving.

I wrote for about five or 10 minutes in my notebook, and wrote what was running through me. My experiences and deepest longings leapt straight from my heart and out onto the page through my hand, and the act of writing became so simple and direct that it was as if my brain was just a spectator, anxious mutterings quieted at last. By the time I finished, I was quietly sobbing in that dark corner of the library, in the sheltered desk carrel that shielded me from the rest of the campus studying on that day in late September of 2002. Something was unleashed that day, and I was so moved by that feeling of being granted permission to write any way I wanted that I dated that page in Writing Down the Bones. Something big happened here today.

I kept that book with me, when things were great and when things were shitty, when I felt despair or years of writer’s block or crippling fear. It’s okay, just write for 10 minutes. Natalie has given me permission to write the worst junk imaginable, because it is the practice that matters. Now, more than a decade later, in my writing sessions, I can finally distinguish the feeling of the juice, the flow of when I’m finally cooking with gas or sparks are flying—pick your metaphor—and I can channel that energy into whatever feels important to work on. But first I have to warm up. Even if I’m writing every day consistently, I still have to shake off the rust and the stiff joints and re-enter the river of writing, the thrall of my own subconscious voice, in order to be receptive enough to conduct electricity when lightning strikes. When I’m stuck, I open up Writing Down the Bones and read:

Be Specific

Be specific. Don’t say ‘fruit.’ Tell what kind of fruit—‘It is a pomegranate.’ Give things the dignity of their names.

Don’t Marry the Fly

Watch when you listen to a piece of writing. There might be spaces where your mind wanders.

A New Moment

Katagiri Roshi often used to say: ‘Take one step off a hundred-foot pole.’

3.

One paradox of my writer’s toolbox of books is that I don’t often write at my writing desk—preferring instead the anonymous yet community feel of a table at my local coffee shop. But I tend to carry that dog-eared and war-torn copy of Writing Down the Bones with me wherever I go. Sometimes I switch it out for my almost-as-demolished copy of Bird by Bird by Anne Lamott, which is funnier and a bit more genre-specific about writing fiction. Over the years, I have trafficked through copies of The Artist’s Way by Julia Cameron, On Writing by Stephen King, Zen and the Art of Writing by Ray Bradbury, Still Writing by Dani Shapiro, and Truth and Beauty by Ann Patchett—which technically isn’t a craft book, but I lump it in, because it’s a memoir of being a young unpublished writer and of “making it,” documenting one particularly deep writing friendship. You could say that I’m a craft book junkie. You could say that.

I also keep books around that remind me of what I love about good writing. I have books that I reread just for the feeling of basking in good writing, like snuggling under a warm blanket or quenching my thirst with a perfectly cold glass of water. Novels like The Mysteries of Pittsburgh, Motherless Brooklyn, A Visit from the Goon Squad, Fight Club, and the Unbearable Lightness of Being are some of these books, and in college, along with the books I was reading for classes, I kept a “greatest hits” shelf of books that made me feel better just by dint of their being nearby.

Yet I don’t own a dictionary. My fiancé, a recreational poet, has a rhyming dictionary, which it has never occurred to me to purchase. I use an online thesaurus regularly at work, but in this digital age, I would never buy a hardcover copy.

Recently, I picked up a copy of Scratch: Writers, Money, and the Art of Making a Living, which I think of as a kind of lifestyle companion for writers delusional enough to think they might someday might make real money from this. It has anecdotal guidance and moral support for writers and those pursuing the writing life, a type of useful and practical advice that reminds me of my regular bimonthly Poets & Writers arrival. My subscription always seems on the verge of lapsing, but I read the magazine cover to cover whenever it arrives. I read the Residencies and Conferences and Grants and Awards sections with a pen in my hand.

4.

I was giddy but apprehensive about my gift of Garner’s Modern Usage. My first thought was, I should bring this to work! In my office, my windowsill-turned-bookshelf has on it a weathered copy of William Zinsser’s On Writing Well, an ancient copy of William Strunk Jr. and E.B. White’s Elements of Style, an untouched copy of the AP Style Guide, and Bill Bryson’s Dictionary for Writers and Editors. The latter is interesting but not comprehensive, so I eventually stopped looking up entries that didn’t exist. But it has a beautiful cover.

My second thought was, Screw work, I want to keep this at home and use it for my own writing at my writing desk! My immediate third thought was, I have to clean my writing desk! Lacking bookshelf space, I started stacking books I’ve just read or want to read on one corner of the small wooden desk I shellacked with rejection slips years ago, back when literary magazines sent paper rejections. I have a tiny ceramic lamp that sits on the other corner of the desk, and without a home office space larger than the footprint of this desk, I’ve collected a variety of other things on its surface—papers, folders, envelopes, DVDs, an unpaid doctor’s bill. My checkbook, more books I’m planning to read, recent drafts of novel revisions, with all manner of handbags and tote bags hanging off the handles of my desk chair like a flea market handbag stall.

[millions_ad]

Could a single modern usage book revolutionize my home writing space and daily writing practice?

I’ve always thought of myself as a writing nomad. Natalie says,

Write Anyplace. Okay. Your kids are climbing into the cereal box. You have $1.25 left in your checking account. Your husband can’t find his shoes, your car won’t start, you know you have lived a life of unfulfilled dreams….Take out another notebook, pick up another pen, and just write, just write, just write. In the middle of the world, make one positive step. In the center of chaos, make one definitive act. Just write.

I write her words, copy them into my notebook, and in that moment, I am reborn. I like having authorities, teachers, mentors on the page. Natalie has taught me a great deal in the 15 years that I’ve been reading and rereading her book.

Maybe Bryan Garner can become my newest teacher on the page, in his witty biting asides about “eventuate” and “insofar as” and many other linguistic predicaments that I have yet to identify. Of course, one great appeal of having the voice of Garner giving me authoritative advice on proper usage is that hovering over his shoulder is the friendly specter of David Foster Wallace, and next to him, my dad nodding along and laughing at my enthusiasm. When he gifted me the book, he said, “This is a great reference for a writer.” It’s in those tiny moments that I feel his slight seal of approval, or at least simple affirmation, of that life that I’ve chosen for myself. He sees me as a writer. Thanks, dad.

Post-40 Bloomers: Marcie Rendon Creates Mirrors for Native People

The post was produced in partnership with Bloom, a literary site that features authors whose first books were published when they were 40 or older.

What is now recognized as the “first Thanksgiving” took place nearly 400 years ago, in 1621, when members of the Wampanoag tribe and Pilgrim settlers sat down together for a three-day feast. The Thanksgiving meal is still central to the occasion today, but we also connect it to a range of other associations—from football to potentially challenging conversations with family to the encroachment of Black Friday. There’s no doubt the holiday has changed. Yet, for some, the image of Native people has not.

When Marcie Rendon was a child, the only representations she saw of her community were set in a distant past that had no bearing on her present reality. Her debut novel Murder on the Red River (Cinco Puntos Press), which was longlisted for the Center for Fiction’s First Novel Award, tackles that issue head-on by introducing readers to a young Native woman who is very much an inhabitant of the 20th century.

Renee “Cash” Blackbear is a 19-year-old farm laborer and pool shark who finds herself embroiled in a murder mystery. Having entered the foster system as a child, Cash has a long history with the local sheriff, who is happy to have her help investigating the death of an unfamiliar Native man. Désirée Zamorano wrote in the LA Review of Books: “Rendon, a member of the White Earth Anishinabe Nation, masterfully weaves two stories in a seamless, vivid narrative. The first is that of a dead Indian found stabbed in his chest without money or ID; the second is that of Cash’s life, and how she came to be a cue-stick-slinging farm hand, playing pool and sleeping with her married lover.”

This is Rendon’s first novel, and her children’s book, Pow Wow Summer, was reprinted in 2014. She is a recipient of the Loft’s Inroads Writers of Color Award for Native Americans. Rendon generously agreed to talk with Bloom about Murder on the Red River and her writing process.

Ericka Taylor: Are you a reader/fan of the murder mystery genre? Who are some of your influences in this genre?

Marcie Rendon: Yes, I read murder mysteries, psychological thrillers, and action thrillers—what I call airport novels. I have been a longtime reader of Stephen King. In my opinion he is the ‘best’ storyteller. The other authors I gravitate to are John Sanford, Lee Child, and the Kellermans. After reading one book of Henning Mankell’s in his Wallander series, I went online and ordered them all and binge read them all. I love King as a storyteller: the first time I visited Maine I "remembered" being there and had to remind myself I only thought that because of reading King. Sanford’s books are easy to read, even while taking you on a roller coaster ride of murder and chaos. I think (though I don’t know because I’ve never talked to him) his writing is so good because he is a journalist. There isn’t a lot of "extra"—which I find time consuming and annoying—in his writing. I want the story.

ET: Murder on the Red River is not a typical murder mystery in that Cash has access to clues and investigative tools unavailable to (or, at least not often used by) traditional law enforcement. She doesn’t only use her dreams and visions to guide her, but also eavesdrops on suspicious conversations and tails potential suspects. How did you decide when to apply the various skills Cash has at her disposal?

MR: My writing process is character driven not "format" or "outline" driven so the story evolved as the character evolved. The skills Cash used were determined by the situation she found herself in.

ET: What was most clear to you about the character Cash, then, when you started the novel? What traits and experiences evolved as you wrote? Did you “discover” things about her as you wrote? If so, anything surprising?

MR: Cash, the character that appeared was, and continues to be, very compelling and insistent on where the story is going. There is the tough bar girl but underneath all that is the vulnerable young woman who survived a lot growing up. She is very smart, both intellectually and with common sense. When I re-read parts of the book I notice how detached she is from much of the heartbreak in her life. In today’s world she would be diagnosed with PTSD.

ET: Place is prominent in the novel, and you really ground the reader in both the history and geography of the region. The only chapter headings in the book refer to the setting, based first in Fargo on the North Dakota side of the Red River and then in Moorhead on the Minnesota side. The Red Lake Reservation is also a key location. Could you tell us about your decision to make place central to the book and what you were hoping it would evoke?

MR: I grew up on the edges of the White Earth Reservation, in and around the Red River Valley, so it is country and landscape that is home to me and is familiar to me. As Native people we have never left our homeland, we are home—so place is our experience on this continent. We know who we are, and where we are from. We are not newcomers to the idea that the Earth is a living entity. It makes sense that in my writing the land is as much a character as the human characters. Prior to European contact, the state lines we know as they exist in the United States did not exist in Native worldview. I believe the same is true for many farmers. They farm the land and have a relationship with the land and the weather and changing seasons. The place settings of North Dakota side and Minnesota side of the Red River were included to help the reader understand the current demarcation between the two states, the two cities of Fargo-Moorhead and the Red River as the dividing line.

ET: Are there also metaphorical/thematic ideas embodied in that dividing line?

MR: As always, one can conjecture the divisions and boundaries that exist because of gender, class, and race. There are lines that we can use to divide us or there are rivers and fields of life that sustain us all. I think as humans we need to decide which is important to us—the divisions or the sustenance.

ET: When you set out to create this mystery, did you already know whodunit, or was that something you discovered through the writing process?

MR: I knew at the beginning that it was a non-Native person who did the killing. I learned as I wrote the number of men involved in the situation and their reason for doing so.

ET: Can you say more about that, i.e. the murderer was a “type” of person before an actual person with motives—what was your interest in establishing that from the outset?

MR: This story called for this “type” of person to have done the dirty deed. In another story, it could easily be the other way around; or another type of person completely; i.e. a woman killing a man. This story just happened to call for this particular situation. I have a short story that will be published in an upcoming Sisters In Crime anthology here in Minnesota. The murderer in that story is a young, pre-teen, Native girl. I guess for me it all depends on where the muse takes me or asks to be taken.

ET: Cash suffered the horror of being raised in foster care with white families who saw her not as a child, but as free labor. How much did exploring that phenomenon, which shifted a bit with the 1978 passing of the Indian Child Welfare Law, shape the timeframe (1970s) in which you set the story?

MR: Cash is the one who set the time and place for the story to occur. I, as a Native writer, was not exploring the phenomenon of foster care when I was writing. I was just writing a story, what to my mind was a murder mystery. It was during the editing process when my editor started asking questions about the foster care story in the background that I also realized, yes, that story was there. It is a story that is so much a fabric of the existence of Native people during that time in history that I wasn’t even aware it was something I was writing about. This was “normal” during that time.

ET: Would you say that the editorial process made you more “audience aware”? And if so, how else did that awareness shape the editing/revision process.

MR: In the editing process I became more cognizant of cultural differences, knowledge bases, and perceptions. Years ago I wrote a play about Sacajawea. During the research necessary for the writing of that play I realized that Sacajawea never had her story told. The story that is told is Lewis and Clark’s story—and as white men who had a written language, everything that has been written about Sacajawea has been written from their white, male perception, not from the mind and heart of a 12 year old girl-child, stolen, raped, beaten and then used as bait to cross the continent. We would know a totally different version of her story if She had had a written language, a way to record Her story. All that to say . . . as my wonderful editor Lee Byrd worked with me, she was able to direct me to places where I was writing from a Native-centric worldview that not all non-Native people have been exposed to, and there were places to expand a bit so the non-Native reader would have a better understanding of the overall story.

ET: Do you generally think about or concern yourself with who you’re writing for?

MR: My primary goal as an Ojibwe woman writer is to create mirrors for my people. My hope is that I am writing stories that everyone can enjoy.

ET: Although Cash is a work of fiction, she, like her creator, has an interest in poetry. Are there any other similarities that you and Cash share?

MR: I used to shoot pool, love shooting pool. And as mentioned previously, I grew up in the Red River Valley.

ET: Is it as uncommon as it seems in the novel for a woman to be so good at and involved in pool culture where you grew up?

MR: I think in the Native community there are fewer gender stereotypes. Women shoot pool, play baseball or softball. There are a good handful of Native American boxers. In this story Cash is the pool shark. If Cash spent more time on any of the nearby reservations I am sure she would encounter other Native women who would give her a run for her money at the tables.

ET: You’ve talked about the importance of making sure Native youth see current Native images, rather than only seeing reflections of themselves that exist in the past. How much does that desire shape your writing projects? Were you exposed to literary images of present-day Native Americans in your youth?

MR: As a child, it was next to impossible to find a book that featured Native people who were not the stereotypical Indians on the Plains, riding horseback and wearing a headdress. And that is who was featured in movies and on TV. With the exception of learning false stories about Pocahontas and Sacajawea in Social Studies classes Native women weren’t mentioned at all. So one of my primary goals in all my writing is to create mirrors for Native people to see themselves.

ET: In addition to being a novelist, you’re also a poet, playwright, and author of children’s books. Do you feel more drawn to one form over another?

MR: I do write a lot of poetry and someday will find a publisher for a book of poems. To date most are in various anthologies featuring Native women poets. I do wish I had more time to devote to writing plays. To see characters brought to life on stage is very fulfilling. But I love to write—I love the stringing of words together to create image, story, and life.

ET: Could you tell us a bit about your writing process? Do you have an established routine where you write at a certain time every day or is it more catch as catch can? Do you prefer to write by hand or on a computer?