Mentioned in:

Most Anticipated: The Great Winter 2025 Preview

It's cold, it's grey, its bleak—but winter, at the very least, brings with it a glut of anticipation-inducing books. Here you’ll find nearly 100 titles that we’re excited to cozy up with this season. Some we’ve already read in galley form; others we’re simply eager to devour based on their authors, subjects, or blurbs. We'd love for you to find your next great read among them.

The Millions will be taking a hiatus for the next few months, but we hope to see you soon.

—Sophia Stewart, editor

January

The Legend of Kumai by Shirato Sanpei, tr. Richard Rubinger (Drawn & Quarterly)

The epic 10-volume series, a touchstone of longform storytelling in manga now published in English for the first time, follows outsider Kamui in 17th-century Japan as he fights his way up from peasantry to the prized role of ninja. —Michael J. Seidlinger

The Life of Herod the Great by Zora Neale Hurston (Amistad)

In the years before her death in 1960, Hurston was at work on what she envisioned as a continuation of her 1939 novel, Moses, Man of the Mountain. Incomplete, nearly lost to fire, and now published for the first time alongside scholarship from editor Deborah G. Plant, Hurston’s final manuscript reimagines Herod, villain of the New Testament Gospel accounts, as a magnanimous and beloved leader of First Century Judea. —Jonathan Frey

Mood Machine by Liz Pelly (Atria)

When you eagerly posted your Spotify Wrapped last year, did you notice how much of what you listened to tended to sound... the same? Have you seen all those links to Bandcamp pages your musician friends keep desperately posting in the hopes that maybe, just maybe, you might give them money for their art? If so, this book is for you. —John H. Maher

My Country, Africa by Andrée Blouin (Verso)

African revolutionary Blouin recounts a radical life steeped in activism in this vital autobiography, from her beginnings in a colonial orphanage to her essential role in the continent's midcentury struggles for decolonization. —Sophia M. Stewart

The First and Last King of Haiti by Marlene L. Daut (Knopf)

Donald Trump repeatedly directs extraordinary animus towards Haiti and Haitians. This biography of Henry Christophe—the man who played a pivotal role in the Haitian Revolution—might help Americans understand why. —Claire Kirch

The Bewitched Bourgeois by Dino Buzzati, tr. Lawrence Venuti (NYRB)

This is the second story collection, and fifth book, by the absurdist-leaning midcentury Italian writer—whose primary preoccupation was war novels that blend the brutal with the fantastical—to get the NYRB treatment. May it not be the last. —JHM

Y2K by Colette Shade (Dey Street)

The recent Y2K revival mostly makes me feel old, but Shade's essay collection deftly illuminates how we got here, connecting the era's social and political upheavals to today. —SMS

Darkmotherland by Samrat Upadhyay (Penguin)

In a vast dystopian reimagining of Nepal, Upadhyay braids narratives of resistance (political, personal) and identity (individual, societal) against a backdrop of natural disaster and state violence. The first book in nearly a decade from the Whiting Award–winning author of Arresting God in Kathmandu, this is Upadhyay’s most ambitious yet. —JF

Metamorphosis by Ross Jeffery (Truborn)

From the author of I Died Too, But They Haven’t Buried Me Yet, a woman leads a double life as she loses her grip on reality by choice, wearing a mask that reflects her inner demons, as she descends into a hell designed to reveal the innermost depths of her grief-stricken psyche. —MJS

The Containment by Michelle Adams (FSG)

Legal scholar Adams charts the failure of desegregation in the American North through the story of the struggle to integrate suburban schools in Detroit, which remained almost completely segregated nearly two decades after Brown v. Board. —SMS

Death of the Author by Nnedi Okorafor (Morrow)

African Futurist Okorafor’s book-within-a-book offers interchangeable cover images, one for the story of a disabled, Black visionary in a near-present day and the other for the lead character’s speculative posthuman novel, Rusted Robots. Okorafor deftly keeps the alternating chapters and timelines in conversation with one another. —Nathalie op de Beeck

Open Socrates by Agnes Callard (Norton)

Practically everything Agnes Callard says or writes ushers in a capital-D Discourse. (Remember that profile?) If she can do the same with a study of the philosophical world’s original gadfly, culture will be better off for it. —JHM

Aflame by Pico Iyer (Riverhead)

Presumably he finds time to eat and sleep in there somewhere, but it certainly appears as if Iyer does nothing but travel and write. His latest, following 2023’s The Half Known Life, makes a case for the sublimity, and necessity, of silent reflection. —JHM

The In-Between Bookstore by Edward Underhill (Avon)

A local bookstore becomes a literal portal to the past for a trans man who returns to his hometown in search of a fresh start in Underhill's tender debut. —SMS

Good Girl by Aria Aber (Hogarth)

Aber, an accomplished poet, turns to prose with a debut novel set in the electric excess of Berlin’s bohemian nightlife scene, where a young German-born Afghan woman finds herself enthralled by an expat American novelist as her country—and, soon, her community—is enflamed by xenophobia. —JHM

The Orange Eats Creeps by Grace Krilanovich (Two Dollar Radio)

Krilanovich’s 2010 cult classic, about a runaway teen with drug-fueled ESP who searches for her missing sister across surreal highways while being chased by a killer named Dactyl, gets a much-deserved reissue. —MJS

Mona Acts Out by Mischa Berlinski (Liveright)

In the latest novel from the National Book Award finalist, a 50-something actress reevaluates her life and career when #MeToo allegations roil the off-off-Broadway Shakespearean company that has cast her in the role of Cleopatra. —SMS

Something Rotten by Andrew Lipstein (FSG)

A burnt-out couple leave New York City for what they hope will be a blissful summer in Denmark when their vacation derails after a close friend is diagnosed with a rare illness and their marriage is tested by toxic influences. —MJS

The Sun Won't Come Out Tomorrow by Kristen Martin (Bold Type)

Martin's debut is a cultural history of orphanhood in America, from the 1800s to today, interweaving personal narrative and archival research to upend the traditional "orphan narrative," from Oliver Twist to Annie. —SMS

We Do Not Part by Han Kang, tr. E. Yaewon and Paige Aniyah Morris (Hogarth)

Kang’s Nobel win last year surprised many, but the consistency of her talent certainly shouldn't now. The latest from the author of The Vegetarian—the haunting tale of a Korean woman who sets off to save her injured friend’s pet at her home in Jeju Island during a deadly snowstorm—will likely once again confront the horrors of history with clear eyes and clarion prose. —JHM

We Are Dreams in the Eternal Machine by Deni Ellis Béchard (Milkweed)

As the conversation around emerging technology skews increasingly to apocalyptic and utopian extremes, Béchard’s latest novel adopts the heterodox-to-everyone approach of embracing complexity. Here, a cadre of characters is isolated by a rogue but benevolent AI into controlled environments engineered to achieve their individual flourishing. The AI may have taken over, but it only wants to best for us. —JF

The Harder I Fight the More I Love You by Neko Case (Grand Central)

Singer-songwriter Case, a country- and folk-inflected indie rocker and sometime vocalist for the New Pornographers, takes her memoir’s title from her 2013 solo album. Followers of PNW music scene chronicles like Kathleen Hanna’s Rebel Girl and drummer Steve Moriarty’s Mia Zapata and the Gits will consider Case’s backstory a must-read. —NodB

The Loves of My Life by Edmund White (Bloomsbury)

The 85-year-old White recounts six decades of love and sex in this candid and erotic memoir, crafting a landmark work of queer history in the process. Seminal indeed. —SMS

Blob by Maggie Su (Harper)

In Su’s hilarious debut, Vi Liu is a college dropout working a job she hates, nothing really working out in her life, when she stumbles across a sentient blob that she begins to transform as her ideal, perfect man that just might resemble actor Ryan Gosling. —MJS

Sinkhole and Other Inexplicable Voids by Leyna Krow (Penguin)

Krow’s debut novel, Fire Season, traced the combustible destinies of three Northwest tricksters in the aftermath of an 1889 wildfire. In her second collection of short fiction, Krow amplifies surreal elements as she tells stories of ordinary lives. Her characters grapple with deadly viruses, climate change, and disasters of the Anthropocene’s wilderness. —NodB

Black in Blues by Imani Perry (Ecco)

The National Book Award winner—and one of today's most important thinkers—returns with a masterful meditation on the color blue and its role in Black history and culture. —SMS

Too Soon by Betty Shamieh (Avid)

The timely debut novel by Shamieh, a playwright, follows three generations of Palestinian American women as they navigate war, migration, motherhood, and creative ambition. —SMS

How to Talk About Love by Plato, tr. Armand D'Angour (Princeton UP)

With modern romance on its last legs, D'Angour revisits Plato's Symposium, mining the philosopher's masterwork for timeless, indispensable insights into love, sex, and attraction. —SMS

At Dark, I Become Loathsome by Eric LaRocca (Blackstone)

After Ashley Lutin’s wife dies, he takes the grieving process in a peculiar way, posting online, “If you're reading this, you've likely thought that the world would be a better place without you,” and proceeds to offer a strange ritual for those that respond to the line, equally grieving and lost, in need of transcendence. —MJS

February

No One Knows by Osamu Dazai, tr. Ralph McCarthy (New Directions)

A selection of stories translated in English for the first time, from across Dazai’s career, demonstrates his penchant for exploring conformity and society’s often impossible expectations of its members. —MJS

Mutual Interest by Olivia Wolfgang-Smith (Bloomsbury)

This queer love story set in post–Gilded Age New York, from the author of Glassworks (and one of my favorite Millions essays to date), explores on sex, power, and capitalism through the lives of three queer misfits. —SMS

Pure, Innocent Fun by Ira Madison III (Random House)

This podcaster and pop culture critic spoke to indie booksellers at a fall trade show I attended, regaling us with key cultural moments in the 1990s that shaped his youth in Milwaukee and being Black and gay. If the book is as clever and witty as Madison is, it's going to be a winner. —CK

Gliff by Ali Smith (Pantheon)

The Scottish author has been on the scene since 1997 but is best known today for a seasonal quartet from the late twenty-teens that began in 2016 with Autumn and ended in 2020 with Summer. Here, she takes the genre turn, setting two children and a horse loose in an authoritarian near future. —JHM

Land of Mirrors by Maria Medem, tr. Aleshia Jensen and Daniela Ortiz (D&Q)

This hypnotic graphic novel from one of Spain's most celebrated illustrators follows Antonia, the sole inhabitant of a deserted town, on a color-drenched quest to preserve the dying flower that gives her purpose. —SMS

Bibliophobia by Sarah Chihaya (Random House)

As odes to the "lifesaving power of books" proliferate amid growing literary censorship, Chihaya—a brilliant critic and writer—complicates this platitude in her revelatory memoir about living through books and the power of reading to, in the words of blurber Namwali Serpell, "wreck and redeem our lives." —SMS

Reading the Waves by Lidia Yuknavitch (Riverhead)

Yuknavitch continues the personal story she began in her 2011 memoir, The Chronology of Water. More than a decade after that book, and nearly undone by a history of trauma and the death of her daughter, Yuknavitch revisits the solace she finds in swimming (she was once an Olympic hopeful) and in her literary community. —NodB

The Dissenters by Youssef Rakha (Graywolf)

A son reevaluates the life of his Egyptian mother after her death in Rakha's novel. Recounting her sprawling life story—from her youth in 1960s Cairo to her experience of the 2011 Tahrir Square protests—a vivid portrait of faith, feminism, and contemporary Egypt emerges. —SMS

Tetra Nova by Sophia Terazawa (Deep Vellum)

Deep Vellum has a particularly keen eye for fiction in translation that borders on the unclassifiable. This debut from a poet the press has published twice, billed as the story of “an obscure Roman goddess who re-imagines herself as an assassin coming to terms with an emerging performance artist identity in the late-20th century,” seems right up that alley. —JHM

David Lynch's American Dreamscape by Mike Miley (Bloomsbury)

Miley puts David Lynch's films in conversation with literature and music, forging thrilling and unexpected connections—between Eraserhead and "The Yellow Wallpaper," Inland Empire and "mixtape aesthetics," Lynch and the work of Cormac McCarthy. Lynch devotees should run, not walk. —SMS

There's No Turning Back by Alba de Céspedes, tr. Ann Goldstein (Washington Square)

Goldstein is an indomitable translator. Without her, how would you read Ferrante? Here, she takes her pen to a work by the great Cuban-Italian writer de Céspedes, banned in the fascist Italy of the 1930s, that follows a group of female literature students living together in a Roman boarding house. —JHM

Beta Vulgaris by Margie Sarsfield (Norton)

Named for the humble beet plant and meaning, in a rough translation from the Latin, "vulgar second," Sarsfield’s surreal debut finds a seasonal harvest worker watching her boyfriend and other colleagues vanish amid “the menacing but enticing siren song of the beets.” —JHM

People From Oetimu by Felix Nesi, tr. Lara Norgaard (Archipelago)

The center of Nesi’s wide-ranging debut novel is a police station on the border between East and West Timor, where a group of men have gathered to watch the final of the 1998 World Cup while a political insurgency stirs without. Nesi, in English translation here for the first time, circles this moment broadly, reaching back to the various colonialist projects that have shaped Timor and the lives of his characters. —JF

Brother Brontë by Fernando A. Flores (MCD)

This surreal tale, set in a 2038 dystopian Texas is a celebration of resistance to authoritarianism, a mash-up of Olivia Butler, Ray Bradbury, and John Steinbeck. —CK

Alligator Tears by Edgar Gomez (Crown)

The High-Risk Homosexual author returns with a comic memoir-in-essays about fighting for survival in the Sunshine State, exploring his struggle with poverty through the lens of his queer, Latinx identity. —SMS

Theory & Practice by Michelle De Kretser (Catapult)

This lightly autofictional novel—De Krester's best yet, and one of my favorite books of this year—centers on a grad student's intellectual awakening, messy romantic entanglements, and fraught relationship with her mother as she minds the gap between studying feminist theory and living a feminist life. —SMS

The Lamb by Lucy Rose (Harper)

Rose’s cautionary and caustic folk tale is about a mother and daughter who live alone in the forest, quiet and tranquil except for the visitors the mother brings home, whom she calls “strays,” wining and dining them until they feast upon the bodies. —MJS

Disposable by Sarah Jones (Avid)

Jones, a senior writer for New York magazine, gives a voice to America's most vulnerable citizens, who were deeply and disproportionately harmed by the pandemic—a catastrophe that exposed the nation's disregard, if not outright contempt, for its underclass. —SMS

No Fault by Haley Mlotek (Viking)

Written in the aftermath of the author's divorce from the man she had been with for 12 years, this "Memoir of Romance and Divorce," per its subtitle, is a wise and distinctly modern accounting of the end of a marriage, and what it means on a personal, social, and literary level. —SMS

Enemy Feminisms by Sophie Lewis (Haymarket)

Lewis, one of the most interesting and provocative scholars working today, looks at certain malignant strains of feminism that have done more harm than good in her latest book. In the process, she probes the complexities of gender equality and offers an alternative vision of a feminist future. —SMS

Lion by Sonya Walger (NYRB)

Walger—an successful actor perhaps best known for her turn as Penny Widmore on Lost—debuts with a remarkably deft autobiographical novel (published by NYRB no less!) about her relationship with her complicated, charismatic Argentinian father. —SMS

The Voices of Adriana by Elvira Navarro, tr. Christina MacSweeney (Two Lines)

A Spanish writer and philosophy scholar grieves her mother and cares for her sick father in Navarro's innovative, metafictional novel. —SMS

Autotheories ed. Alex Brostoff and Vilashini Cooppan (MIT)

Theory wonks will love this rigorous and surprisingly playful survey of the genre of autotheory—which straddles autobiography and critical theory—with contributions from Judith Butler, Jamieson Webster, and more.

Fagin the Thief by Allison Epstein (Doubleday)

I enjoy retellings of classic novels by writers who turn the spotlight on interesting minor characters. This is an excursion into the world of Charles Dickens, told from the perspective iconic thief from Oliver Twist. —CK

Crush by Ada Calhoun (Viking)

Calhoun—the masterful memoirist behind the excellent Also A Poet—makes her first foray into fiction with a debut novel about marriage, sex, heartbreak, all-consuming desire. —SMS

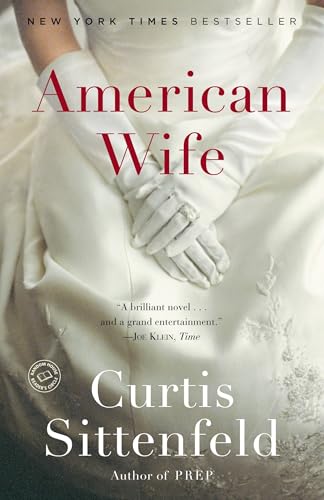

Show Don't Tell by Curtis Sittenfeld (Random House)

Sittenfeld's observations in her writing are always clever, and this second collection of short fiction includes a tale about the main character in Prep, who visits her boarding school decades later for an alumni reunion. —CK

Right-Wing Woman by Andrea Dworkin (Picador)

One in a trio of Dworkin titles being reissued by Picador, this 1983 meditation on women and American conservatism strikes a troublingly resonant chord in the shadow of the recent election, which saw 45% of women vote for Trump. —SMS

The Talent by Daniel D'Addario (Scout)

If your favorite season is awards, the debut novel from D'Addario, chief correspondent at Variety, weaves an awards-season yarn centering on five stars competing for the Best Actress statue at the Oscars. If you know who Paloma Diamond is, you'll love this. —SMS

Death Takes Me by Cristina Rivera Garza, tr. Sarah Booker and Robin Myers (Hogarth)

The Pulitzer winner’s latest is about an eponymously named professor who discovers the body of a mutilated man with a bizarre poem left with the body, becoming entwined in the subsequent investigation as more bodies are found. —MJS

The Strange Case of Jane O. by Karen Thompson Walker (Random House)

Jane goes missing after a sudden a debilitating and dreadful wave of symptoms that include hallucinations, amnesia, and premonitions, calling into question the foundations of her life and reality, motherhood and buried trauma. —MJS

Song So Wild and Blue by Paul Lisicky (HarperOne)

If it weren’t Joni Mitchell’s world with all of us just living in it, one might be tempted to say the octagenarian master songstress is having a moment: this memoir of falling for the blue beauty of Mitchell’s work follows two other inventive books about her life and legacy: Ann Powers's Traveling and Henry Alford's I Dream of Joni. —JHM

Mornings Without Mii by Mayumi Inaba, tr. Ginny Tapley (FSG)

A woman writer meditates on solitude, art, and independence alongside her beloved cat in Inaba's modern classic—a book so squarely up my alley I'm somehow embarrassed. —SMS

True Failure by Alex Higley (Coffee House)

When Ben loses his job, he decides to pretend to go to work while instead auditioning for Big Shot, a popular reality TV show that he believes might be a launchpad for his future successes. —MJS

March

Woodworking by Emily St. James (Crooked Reads)

Those of us who have been reading St. James since the A.V. Club days may be surprised to see this marvelous critic's first novel—in this case, about a trans high school teacher befriending one of her students, the only fellow trans woman she’s ever met—but all the more excited for it. —JHM

Optional Practical Training by Shubha Sunder (Graywolf)

Told as a series of conversations, Sunder’s debut novel follows its recently graduated Indian protagonist in 2006 Cambridge, Mass., as she sees out her student visa teaching in a private high school and contriving to find her way between worlds that cannot seem to comprehend her. Quietly subversive, this is an immigration narrative to undermine the various reductionist immigration narratives of our moment. —JF

Love, Queenie by Mayukh Sen (Norton)

Merle Oberon, one of Hollywood's first South Asian movie stars, gets her due in this engrossing biography, which masterfully explores Oberon's painful upbringing, complicated racial identity, and much more. —SMS

The Age of Choice by Sophia Rosenfeld (Princeton UP)

At a time when we are awash with options—indeed, drowning in them—Rosenfeld's analysis of how our modingn idea of "freedom" became bound up in the idea of personal choice feels especially timely, touching on everything from politics to romance. —SMS

Sucker Punch by Scaachi Koul (St. Martin's)

One of the internet's funniest writers follows up One Day We'll All Be Dead and None of This Will Matter with a sharp and candid collection of essays that sees her life go into a tailspin during the pandemic, forcing her to reevaluate her beliefs about love, marriage, and what's really worth fighting for. —SMS

The Mysterious Disappearance of the Marquise of Loria by José Donoso, tr. Megan McDowell (New Directions)

The ever-excellent McDowell translates yet another work by the influential Chilean author for New Directions, proving once again that Donoso had a knack for titles: this one follows up 2024’s behemoth The Obscene Bird of Night. —JHM

Remember This by Anthony Giardina (FSG)

On its face, it’s another book about a writer living in Brooklyn. A layer deeper, it’s a book about fathers and daughters, occupations and vocations, ethos and pathos, failure and success. —JHM

Ultramarine by Mariette Navarro (Deep Vellum)

In this metaphysical and lyrical tale, a captain known for sticking to protocol begins losing control not only of her crew and ship but also her own mind. —MJS

We Tell Ourselves Stories by Alissa Wilkinson (Liveright)

Amid a spate of new books about Joan Didion published since her death in 2021, this entry by Wilkinson (one of my favorite critics working today) stands out for its approach, which centers Hollywood—and its meaning-making apparatus—as an essential key to understanding Didion's life and work. —SMS

Seven Social Movements that Changed America by Linda Gordon (Norton)

This book—by a truly renowned historian—about the power that ordinary citizens can wield when they organize to make their community a better place for all could not come at a better time. —CK

Mothers and Other Fictional Characters by Nicole Graev Lipson (Chronicle Prism)

Lipson reconsiders the narratives of womanhood that constrain our lives and imaginations, mining the canon for alternative visions of desire, motherhood, and more—from Kate Chopin and Gwendolyn Brooks to Philip Roth and Shakespeare—to forge a new story for her life. —SMS

Goddess Complex by Sanjena Sathian (Penguin)

Doppelgängers have been done to death, but Sathian's examination of Millennial womanhood—part biting satire, part twisty thriller—breathes new life into the trope while probing the modern realities of procreation, pregnancy, and parenting. —SMS

Stag Dance by Torrey Peters (Random House)

The author of Detransition, Baby offers four tales for the price of one: a novel and three stories that promise to put gender in the crosshairs with as sharp a style and swagger as Peters’ beloved latest. The novel even has crossdressing lumberjacks. —JHM

On Breathing by Jamieson Webster (Catapult)

Webster, a practicing psychoanalyst and a brilliant writer to boot, explores that most basic human function—breathing—to address questions of care and interdependence in an age of catastrophe. —SMS

Unusual Fragments: Japanese Stories (Two Lines)

The stories of Unusual Fragments, including work by Yoshida Tomoko, Nobuko Takai, and other seldom translated writers from the same ranks as Abe and Dazai, comb through themes like alienation and loneliness, from a storm chaser entering the eye of a storm to a medical student observing a body as it is contorted into increasingly violent positions. —MJS

The Antidote by Karen Russell (Knopf)

Russell has quipped that this Dust Bowl story of uncanny happenings in Nebraska is the “drylandia” to her 2011 Florida novel, Swamplandia! In this suspenseful account, a woman working as a so-called prairie witch serves as a storage vault for her townspeople’s most troubled memories of migration and Indigenous genocide. With a murderer on the loose, a corrupt sheriff handling the investigation, and a Black New Deal photographer passing through to document Americana, the witch loses her memory and supernatural events parallel the area’s lethal dust storms. —NodB

On the Clock by Claire Baglin, tr. Jordan Stump (New Directions)

Baglin's bildungsroman, translated from the French, probes the indignities of poverty and service work from the vantage point of its 20-year-old narrator, who works at a fast-food joint and recalls memories of her working-class upbringing. —SMS

Motherdom by Alex Bollen (Verso)

Parenting is difficult enough without dealing with myths of what it means to be a good mother. I who often felt like a failure as a mother appreciate Bollen's focus on a more realistic approach to parenting. —CK

The Magic Books by Anne Lawrence-Mathers (Yale UP)

For that friend who wants to concoct the alchemical elixir of life, or the person who cannot quit Susanna Clark’s Jonathan Strange and Mr. Norrell, Lawrence-Mathers collects 20 illuminated medieval manuscripts devoted to magical enterprise. Her compendium includes European volumes on astronomy, magical training, and the imagined intersection between science and the supernatural. —NodB

Theft by Abdulrazak Gurnah (Riverhead)

The first novel by the Tanzanian-British Nobel laureate since his surprise win in 2021 is a story of class, seismic cultural change, and three young people in a small Tanzania town, caught up in both as their lives dramatically intertwine. —JHM

Twelve Stories by American Women, ed. Arielle Zibrak (Penguin Classics)

Zibrak, author of a delicious volume on guilty pleasures (and a great essay here at The Millions), curates a dozen short stories by women writers who have long been left out of American literary canon—most of them women of color—from Frances Ellen Watkins Harper to Zitkala-Ša. —SMS

I'll Love You Forever by Giaae Kwon (Holt)

K-pop’s sky-high place in the fandom landscape made a serious critical assessment inevitable. This one blends cultural criticism with memoir, using major artists and their careers as a lens through which to view the contemporary Korean sociocultural landscape writ large. —JHM

The Buffalo Hunter Hunter by Stephen Graham Jones (Saga)

Jones, the acclaimed author of The Only Good Indians and the Indian Lake Trilogy, offers a unique tale of historical horror, a revenge tale about a vampire descending upon the Blackfeet reservation and the manifold of carnage in their midst. —MJS

True Mistakes by Lena Moses-Schmitt (University of Arkansas Press)

Full disclosure: Lena is my friend. But part of why I wanted to be her friend in the first place is because she is a brilliant poet. Selected by Patricia Smith as a finalist for the Miller Williams Poetry Prize, and blurbed by the great Heather Christle and Elisa Gabbert, this debut collection seeks to turn "mistakes" into sites of possibility. —SMS

Perfection by Vicenzo Latronico, tr. Sophie Hughes (NYRB)

Anna and Tom are expats living in Berlin enjoying their freedom as digital nomads, cultivating their passion for capturing perfect images, but after both friends and time itself moves on, their own pocket of creative freedom turns boredom, their life trajectories cast in doubt. —MJS

Guatemalan Rhapsody by Jared Lemus (Ecco)

Jemus's debut story collection paint a composite portrait of the people who call Guatemala home—and those who have left it behind—with a cast of characters that includes a medicine man, a custodian at an underfunded college, wannabe tattoo artists, four orphaned brothers, and many more.

Pacific Circuit by Alexis Madrigal (MCD)

The Oakland, Calif.–based contributing writer for the Atlantic digs deep into the recent history of a city long under-appreciated and under-served that has undergone head-turning changes throughout the rise of Silicon Valley. —JHM

Barbara by Joni Murphy (Astra)

Described as "Oppenheimer by way of Lucia Berlin," Murphy's character study follows the titular starlet as she navigates the twinned convulsions of Hollywood and history in the Atomic Age.

Sister Sinner by Claire Hoffman (FSG)

This biography of the fascinating Aimee Semple McPherson, America's most famous evangelist, takes religion, fame, and power as its subjects alongside McPherson, whose life was suffused with mystery and scandal. —SMS

Trauma Plot by Jamie Hood (Pantheon)

In this bold and layered memoir, Hood confronts three decades of sexual violence and searches for truth among the wreckage. Kate Zambreno calls Trauma Plot the work of "an American Annie Ernaux." —SMS

Hey You Assholes by Kyle Seibel (Clash)

Seibel’s debut story collection ranges widely from the down-and-out to the downright bizarre as he examines with heart and empathy the strife and struggle of his characters. —MJS

James Baldwin by Magdalena J. Zaborowska (Yale UP)

Zaborowska examines Baldwin's unpublished papers and his material legacy (e.g. his home in France) to probe about the great writer's life and work, as well as the emergence of the "Black queer humanism" that Baldwin espoused. —CK

Stop Me If You've Heard This One by Kristen Arnett (Riverhead)

Arnett is always brilliant and this novel about the relationship between Cherry, a professional clown, and her magician mentor, "Margot the Magnificent," provides a fascinating glimpse of the unconventional lives of performance artists. —CK

Paradise Logic by Sophie Kemp (S&S)

The deal announcement describes the ever-punchy writer’s debut novel with an infinitely appealing appellation: “debauched picaresque.” If that’s not enough to draw you in, the truly unhinged cover should be. —JHM

[millions_email]

A Year in Reading: 2024

Welcome to the 20th (!) installment of The Millions' annual Year in Reading series, which gathers together some of today's most exciting writers and thinkers to share the books that shaped their year. YIR is not a collection of yearend best-of lists; think of it, perhaps, as an assemblage of annotated bibliographies. We've invited contributors to reflect on the books they read this year—an intentionally vague prompt—and encouraged them to approach the assignment however they choose.

In writing about our reading lives, as YIR contributors are asked to do, we inevitably write about our personal lives, our inner lives. This year, a number of contributors read their way through profound grief and serious illness, through new parenthood and cross-country moves. Some found escape in frothy romances, mooring in works of theology, comfort in ancient epic poetry. More than one turned to the wisdom of Ursula K. Le Guin. Many describe a book finding them just when they needed it.

Interpretations of the assignment were wonderfully varied. One contributor, a music critic, considered the musical analogs to the books she read, while another mapped her reads from this year onto constellations. Most people's reading was guided purely by pleasure, or else a desire to better understand events unfolding in their lives or larger the world. Yet others centered their reading around a certain sense of duty: this year one contributor committed to finishing the six Philip Roth novels he had yet to read, an undertaking that he likens to “eating a six-pack of paper towels.” (Lucky for us, he included in his essay his final ranking of Roth's oeuvre.)

The books that populate these essays range widely, though the most commonly noted title this year was Tony Tulathimutte’s story collection Rejection. The work of newly minted National Book Award winner Percival Everett, particularly his acclaimed novel James, was also widely read and written about. And as the genocide of Palestinians in Gaza enters its second year, many contributors sought out Isabella Hammad’s searing, clear-eyed essay Recognizing the Stranger.

Like so many endeavors in our chronically under-resourced literary community, Year in Reading is a labor of love. The Millions is a one-person editorial operation (with an invaluable assist from SEO maven Dani Fishman), and producing YIR—and witnessing the joy it brings contributors and readers alike—has been the highlight of my tenure as editor. I’m profoundly grateful for the generosity of this year’s contributors, whose names and entries will be revealed below over the next three weeks, concluding on Wednesday, December 18. Be sure to subscribe to The Millions’ free newsletter to get the week’s entries sent straight to your inbox each Friday.

—Sophia Stewart, editor

Becca Rothfeld, author of All Things Are Too Small

Carvell Wallace, author of Another Word for Love

Charlotte Shane, author of An Honest Woman

Brianna Di Monda, writer and editor

Nell Irvin Painter, author of I Just Keep Talking

Carrie Courogen, author of Miss May Does Not Exist

Ayşegül Savaş, author of The Anthropologists

Zachary Issenberg, writer

Tony Tulathimutte, author of Rejection

Ann Powers, author of Traveling: On the Path of Joni Mitchell

Lidia Yuknavitch, author of Reading the Waves

Nicholas Russell, writer and critic

Daniel Saldaña París, author of Planes Flying Over a Monster

Lili Anolik, author of Didion and Babitz

Deborah Ghim, editor

Emily Witt, author of Health and Safety

Nathan Thrall, author of A Day in the Life of Abed Salama

Lena Moses-Schmitt, author of True Mistakes

Jeremy Gordon, author of See Friendship

John Lee Clark, author of Touch the Future

Ellen Wayland-Smith, author of The Science of Last Things

Edwin Frank, publisher and author of Stranger Than Fiction

Sophia Stewart, editor of The Millions

A Year in Reading Archives: 2023, 2022, 2021, 2020, 2019, 2018, 2017, 2016, 2015, 2014, 2013, 2011, 2010, 2009, 2008, 2007, 2006, 2005

June Preview: The Millions Most Anticipated (This Month)

We wouldn’t dream of abandoning our vast semi–annual Most Anticipated Book Previews, but we thought a monthly reminder would be helpful (and give us a chance to note titles we missed the first time around). Here’s what we’re looking out for this month. Let us know what you’re looking forward to in the comments, and get excited for the GREAT SECOND-HALF PREVIEW, which we will roll out in the second week of July.

(Also, as Millions founder and publisher C. Max Magee wrote recently, you can help ensure that these previews, and all our great books coverage, continue for years to come by lending your support to the site as a member. The Millions has been running for nearly 15 years on a wing and a prayer, and we’re incredibly grateful for the love of our recurring readers and current members who help us sustain the work that we do.)

Kudos by Rachel Cusk: When I first encountered Cusk’s writing in the mid-aughts I wrote her off as an author of potentially tedious domestic drama. I was woefully wrong. It’s true Cusk is a chronicler of the domestic: she is as known for her memoirs of motherhood and divorce as she is for her novels, but her writing is innovative, observant, and bold. The New Yorker declared that with the trilogy that her latest novel Kudos completes, Cusk has “renovated” the novel, merging fiction with oral history, retooling its structure. Cusk has said: “I’ve never treated fiction as a veil or as a thing to hide behind, which perhaps was, not a mistake exactly, but a sort of risky way to live.” (Anne)

There There by Tommy Orange: Set mostly in Oakland, Orange’s polyphonic novel describes the disparate but connected lives of group of Native Americans, many of them self-identified "urban Indians," who come together for the Great Oakland Powwow. There, personal and communal and national histories propel events--and his cast of characters--toward a shocking denouement. Orange's novel has been called a "new kind of American epic" by the New York Times; read more here. (Lydia)

Florida by Lauren Groff: After collecting fans like Barack Obama with her bestselling novel Fates and Furies, Groff’s next book is a collection of short stories that center around Florida, “the landscape, climate, history, and state of mind.” Included is ”Dogs Go Wolf,” the haunting story that appeared in The New Yorker earlier in the year. In a recent interview, Groff gave us the lay of the land: “The collection is a portrait of my own incredible ambivalence about the state where I’ve lived for twelve years...I love the disappearing natural world, the sunshine, the extraordinary and astonishing beauty of the place as passionately as I hate the heat and moisture and backward politics and the million creatures whose only wish is to kill you.” (Claire)

Number One Chinese Restaurant by Lillian Li: A family chronicle, workplace drama, and love story rolled into one, Li’s debut chronicles the universe of the Beijing Duck House restaurant of Rockville, Md., run by a family and long-time employees who intertwine in various ways when disaster strikes. Lorrie Moore raves, “her narratives are complex, mysterious, moving, and surprising.” Read an excerpt from the novel here at Buzzfeed. (Lydia)

The Terrible by Yrsa Daley-Ward: A poet's memoir in prose and verse about a tempestuous adolescence in England, where the author was born to immigrant parents and raised by Seventh-Day Adventist grandparents. The memoir describes her experiences with drugs and alcohol, her relationships with men and with sex work, the struggles of her brother, and her development as an artist. A starred Kirkus review says "Daley-Ward has quite a ferociously moving story to tell." (Lydia)

Confessions of the Fox by Jordy Rosenberg: A work of speculative historical fiction exploring queer and trans histories through the story of notorious 19th-century London thieves Jack Sheppard and Edgeworth Bess. This is a publishing event, the first work of fiction to be released by esteemed editor Chris Jackson's One World imprint, and it has received accolades from every trade publication and a host of writers including Victor LaValle, China Miéville, and Maggie Nelson. (Lydia)

Ayiti by Roxane Gay: This is a reissue of Roxane Gay's first book, a collection of short stories about Haiti and the diaspora, with two new stories. Ayiti was first published by the small press Artistically Declined Press in 2011, before the author was routinely at the top of the New York Times bestseller list. Kirkus says "Gay has addressed these subjects with more complexity since, but this debut amply contains the righteous energy that drives all her work." (Lydia)

The Great Believers by Rebecca Makkai: This third novel from the acclaimed author of The Borrower and The Hundred-Year House interlaces the story of an art gallery director whose friends are succumbing to the AIDS epidemic in 1980s Chicago with a mother struggling to find her estranged daughter 30 years later in contemporary Paris. “The Great Believers is by turns funny, harrowing, tender, devastating, and always hugely suspenseful,” says Margot Livesey, author of Mercury. (Michael)

Good Trouble by Joseph O’Neill: Frequent New Yorker and Harper’s readers will know that O’Neill has been writing a lot of short fiction lately. With the new Good Trouble, the Netherland author now has a full collection, comprised of 11 off-kilter, unsettling stories. Their characters range from a would-be renter in New York who can’t get anyone to give him a reference to a poet who can’t decide whether or not to sign a petition. (Thom)

Days of Awe by A.M. Homes: A new collection of stories from the prolific author of May We Be Forgiven featuring humorous, melancholy reflections on American life. The title story involves friends becoming lovers at a conference about genocides. The great Zadie Smith calls it "a razor-sharp story collection from a writer who is always 'furiously good.'" (Lydia)

The Good Son by You-jeong Jeong (translated by Chi-Young Kim): South Korea's best-selling crime novelist is a woman, although she is nonetheless marketed as "the Stephen King of Korea." This novel, a sensation in South Korea and her first to be translated into English, is a psychological thriller involving a possible matricide, for "fans of Jo Nesbo and Patricia Highsmith." (Lydia)

Upstate by James Wood: It’s been 15 years since Wood’s first novel, The Book Against God, was published. What was Wood doing in the meantime? Oh, just influencing a generation of novelists from his perch at The New Yorker, where his dissecting reviews also functioned as miniature writing seminars. He also penned a writing manual, How Fiction Works. His sophomore effort concerns the Querry family, who reunite in upstate New York to help a family member cope with depression and to pose the kinds of questions fiction answers best: How do people get through difficulty? What does it mean to be happy? How should we live our lives? (Hannah)

Convenience Store Woman by Sayaka Murata (translated by Ginny Tapley Takemori): A 36-year-old woman in modern-day Tokyo has worked a convenience store for 18 years of her life, watching family and friends pairing off, having children, or climbing professional ladders. She eventually enters into a sham marriage with a coworker to embody an idealized notion of adulthood, but the plan backfires, and the book is a meditation on work, life, and "normalcy." Kirkus says "Murata skillfully navigates the line between the book’s wry and weighty concerns and ensures readers will never conceive of the 'pristine aquarium' of a convenience store in quite the same way." (Lydia)

Half Gods by Akil Kumarasamy: A collection of linked stories about a family devastated by the Sri Lankan civil war, which claims the lives of a mother and two sons. The father and remaining daughter flee to New Jersey, and the collection moves across time and place and between points of view to describe the dislocation of its characters and the enduring consequences of trauma. Publisher's Weekly calls it "a wonderful, auspicious debut." (Lydia)

History of Violence by Édouard Louis (translated by Lorin Stein): A fictionalized account of a true story. The author survived a violent sexual assault and this novelization exploring the aftermath, including his return to his family's village, became a bestseller in France for its frank reckoning with the effects of sexual violence, as well a broader look at French society. (Lydia)

Sweet and Low by Nick White: A new entry in the field of southern gothic (complete with Faulkner homage), a collection of stories exploring masculinity, sexuality, and place in the deep south that has garnered praise from Jesmyn Ward and Alissa Nutting. Publisher's Weekly called it "an atmospheric and expertly crafted collection." (Lydia)

We Begin Our Ascent by Joe Mungo Reed: A debut novel that follows the travails of a team of professional cyclists--who happen to be doping--in the Tour de France, exploring ideas of competition, ambition, and team dynamics. The novel has drawn several comparisons to Don DeLillo, and George Saunders raved: “A dazzling debut by an exciting and essential new talent: fast, harrowing, compelling, masterfully structured, genuinely moving. Reed is a true stylist.” (Lydia)

Dead Girls by Alice Bolin: A collection of essays exploring the ubiquitous "dead girl" in popular culture, using shows like Twin Peaks and Pretty Little Liars to point to the misogyny that thrums through so many of the cultural products we consume. These are interwoven with personal essays about her arrival in Los Angeles. Kirkus calls it "an illuminating study on the role women play in the media and in their own lives." (Lydia)

Sick by Porochista Khakpour: In her much anticipated memoir, Khakpour chronicles her arduous experience with illness, specifically late-stage Lyme disease. She examines her efforts to receive a diagnosis and the psychological and physiological impact of being so sick for so long, including struggles with mental health and addiction. Khakpour’s memoir demonstrates the power of survival in the midst of pain and uncertainty. (Read an excellent piece in The New Yorker here.) (Zoë)

The Captives by Debra Jo Immergut: Immergut published a collection of short stories in 1992, shortly after graduating from the Iowa Writers' Workshop, but her debut novel comes over 25 years later, a literary thriller that takes place in a prison where a woman is serving a sentence for second-degree murder. Her appointed psychologist once pined for her in high schhol. Publishers' Weekly says "Immergut’s book begins as in incisive psychological portrait of two mismatched individuals and morphs into a nail-biting thriller." (Lydia)

Tonight I’m Someone Else by Chelsea Hodson: Examining the intersection of social media and intimacy, the commercial and the corporeal, the theme of Hodson’s essay collection is how we are pushed and pulled by our desire. The Catapult teacher’s debut has been called “racingly good…refreshing and welcome” by Maggie Nelson. (Tess)

Fight No More by Lydia Millet: Millet’s 2010 collection Love in Infant Monkeys was a Pulitzer Prize finalist. Eight years later she’s released another collection of stories arranged around a real estate broker and their family as they struggle to reconnect. Millet’s satire is well-known for it’s sharp brutality—and its compassionate humanity. Both sides are on full display here. (Kaulie)

Invitation to a Bonfire by Adrienne Celt: On the heels of her critically praised debut, The Daughters, Celt gives us a love-triangle story that, according to the publisher, is “inspired by the infamous Nabokov marriage, with a spellbinding psychological thriller at its core.” The protagonist is a young Russian refugee named Zoya who becomes entangled with her boarding school’s visiting writer, Leo Orlov, and his imperious wife, Vera. Our own Edan Lepucki praised the novel as “a sexy, brilliant, and gripping novel about the fine line between passion and obsession. I am in awe of Celt’s mastery as a prose stylist and storyteller; I can’t stop thinking about this amazing book.” (Sonya)

[millions_ad]

Most Anticipated: The Great 2018 Book Preview

Settle in, folks, because this is one the longest first-half previews we've run in a long while. Putting this together is a labor of love, and while a huge crop of great spring books increases the labor, it also means there is more here for readers to love. We'd never claim to be comprehensive—we know there are far more excellent books on the horizon than one list can hold, which is why we've started doing monthly previews in addition to the semi-annual lists (and look out for the January Poetry Preview, which drops tomorrow). But we feel confident we've put together a fantastic selection of (almost 100!) works of fiction, memoir, and essay to enliven your January through June 2018. What's in here? New fiction by giants like Michael Ondaatje, Helen DeWitt, Lynne Tillman, and John Edgar Wideman. Essays from Zadie Smith, Marilynne Robinson, and Leslie Jamison. Exciting debuts from Nafkote Tamirat, Tommy Orange, and Lillian Li. Thrilling translated work from Leïla Slimani and Clarice Lispector. A new Rachel Kushner. A new Rachel Cusk. The last Denis Johnson. The last William Trevor. The long-awaited Vikram Seth.

As Millions founder and publisher C. Max Magee wrote recently, you can help ensure that these previews, and all our great books coverage, continue for years to come by lending your support to the site as a member. The Millions has been running for nearly 15 years on a wing and a prayer, and we're incredibly grateful for the love of our recurring readers and current members who help us sustain the work that we do.

So don your specs, clear off your TBR surfaces, and prepare for a year that, if nothing else, will be full of good books.

JANUARY

The Perfect Nanny by Leïla Slimani (translated by Sam Taylor): In her Goncourt Prize-winning novel, Slimani gets the bad news out of the way early—on the first page to be exact: “The baby is dead. It only took a few seconds. The doctor said he didn’t suffer. The broken body, surrounded by toys, was put inside a gray bag, which they zipped up.” Translated from the French by Sam Taylor as The Perfect Nanny—the original title was Chanson Douce, or Lullaby—this taut story about an upper-class couple and the woman they hire to watch their child tells of good help gone bad. (Matt)

Halsey Street by Naima Coster: Coster’s debut novel is set in Bedford-Stuyvesant, a rapidly gentrifying corner of Brooklyn. When Penelope Grand leaves a failed art career in Pittsburgh and comes home to Brooklyn to look after her father, she finds her old neighborhood changed beyond recognition. The narrative shifts between Penelope and her mother, Mirella, who abandoned the family to move to the Dominican Republic and longs for reconciliation. A meditation on family, love, gentrification, and home. (Emily)

Fire Sermon by Jamie Quatro: Five years after her story collection, I Want to Show You More, drew raves from The New Yorker’s James Wood and Dwight Garner at The New York Times, Quatro delivers her debut novel, which follows a married woman’s struggle to reconcile a passionate affair with her fierce attachment to her husband and two children. “It’s among the most beautiful books I’ve ever read about longing—for beauty, for sex, for God, for a coherent life,” says Garth Greenwell, author of What Belongs to You. (Michael)

The Largesse of the Sea Maiden by Denis Johnson: Johnson’s writing has always had an antiphonal quality to it—the call and response of a man and his conscience, perhaps. In these stories, a dependably motley crew of Johnson protagonists find themselves forced to take stock as mortality comes calling. The writing has a more plangent tone than Angels and Jesus’ Son, yet is every bit as edgy. Never afraid to look into the abyss, and never cute about it, Johnson will be missed. Gratefully, sentences like the following, his sentences, will never go away: “How often will you witness a woman kissing an amputation?” R.I.P. (Il’ja)

A Girl in Exile by Ismail Kadare (translated by John Hodgson): Kadare structures the novel like a psychological detective yarn, but one with some serious existential heft. The story is set physically in Communist Albania in the darkest hours of totalitarian rule, but the action takes place entirely in the head and life of a typically awful Kadare protagonist—Rudian Stefa, a writer. When a young woman from a remote province ends up dead with a provocatively signed copy of Stefa’s latest book in her possession, it’s time for State Security to get involved. A strong study of the ease and banality of human duplicity. (Il’ja)

Frankenstein in Baghdad by Ahmed Saadawi (translated by Jonathan Wright): The long-awaited English translation of the winner of the International Prize for Arabic Fiction in 2014 gives American readers the opportunity to read Saadawi’s haunting, bleak, and darkly comic take on Iraqi life in 2008. Or, as Saadawi himself put it in interview for Arab Lit, he set out to write “the fictional representation of the process of everyone killing everyone.” (Check out Saadawi's Year in Reading here.) (Nick M.)

This Will Be My Undoing by Morgan Jerkins: Wünderkind Jerkins has a background in 19th-century Russian lit and postwar Japanese lit, speaks six languages, works/has worked as editor and assistant literary agent; she writes across many genres—reportage, personal essays, fiction, profiles, interviews, literary criticism, and sports and pop culture pieces; and now we’ll be seeing her first book, an essay collection. From the publisher: “This is a book about black women, but it’s necessary reading for all Americans.” The collected essays will cover topics ranging from “Rachel Dolezal; the stigma of therapy; her complex relationship with her own physical body; the pain of dating when men say they don’t ‘see color’; being a black visitor in Russia; the specter of ‘the fast-tailed girl’ and the paradox of black female sexuality; or disabled black women in the context of the ‘Black Girl Magic’ movement.” (Sonya)

Mouths Don’t Speak by Katia D. Ulysse: In Drifting, Ulysse’s 2014 story collection, Haitian immigrants struggle through New York City after the 2010 earthquake that destroyed much of their county. In her debut novel, Ulysse revisits that disaster with a clearer and sharper focus. Jacqueline Florestant is mourning her parents, presumed dead after the earthquake, while her ex-Marine husband cares for their young daughter. But the expected losses aren’t the most serious, and a trip to freshly-wounded Haiti exposes the way tragedy follows class lines as well as family ones. (Kaulie)

The Sky Is Yours by Chandler Klang Smith: Smith’s The Sky Is Yours, is a blockbuster of major label debuts. The dystopic inventiveness of this genre hybrid sci-fi thriller/coming of age tale/adventure novel has garnered comparisons to Gary Shteyngart, David Mitchell and Ridley Scott’s Blade Runner. And did I mention? It has dragons, too, circling the crumbling Empire Island, and with them a fire problem (of course), and features a reality TV star from a show called Late Capitalism's Royalty. Victor LaValle calls The Sky Is Yours "a raucous, inventive gem of a debut." Don't just take our word for it, listen to an audio excerpt. (Anne)

Everything Here Is Beautiful by Mira T. Lee: Spanning cultures and continents, Lee’s assured debut novel tells the story of two sisters who are bound together and driven apart by the inescapable bonds of family. Miranda is the sensible one, thrust into the role of protector of Lucia, seven years younger, head-strong, and headed for trouble. Their mother emigrated from China to the U.S. after the death of their father, and as the novel unfurls in clear, accessible prose, we follow the sisters on journeys that cover thousands of miles and take us into the deepest recesses of the human heart. Despite its sunny title, this novel never flinches from big and dark issues, including interracial love, mental illness and its treatment, and the dislocations of immigrant life. (Bill)

The Infinite Future by Tim Wirkus: I read this brilliant puzzle-of-a-book last March and I still think about it regularly! The Infinite Future follows a struggling writer, a librarian, and a Mormon historian excommunicated from the church on their search for a reclusive Brazilian science fiction writer. In a starred review, Book Page compares Wirkus to Jonathan Lethem and Ron Currie Jr., and says the book “announces Wirkus as one of the most exciting novelists of his generation.” I agree. (Edan)

The Job of the Wasp by Colin Winnette: With Winnette’s fourth novel he proves he’s adept at re-appropriating genre conventions in intriguing ways. His previous book, Haint’s Stay, is a Western tale jimmyrigged for its own purposes and is at turns both surreal and humorous. Winnette's latest, The Job of the Wasp, takes on the Gothic ghost novel and is set in the potentially creepiest of places—an isolated boarding school for orphaned boys, in the vein of Robert Walser’s Jakob von Gunten, Jenny Erpenbeck’s The Old Child, or even Charles Dickens’s Oliver Twist. “Witty and grisly” according to Kelly Link, strange and creepy, Job of the Wasp reveals Winnette's "natural talent" says Patrick deWitt. (Anne)

Brass by Xhenet Aliu: In what Publishers Weekly calls a "striking first novel," a daughter searches for answers about the relationship between her parents, a diner waitress from Waterbury, Conn. and a line cook who emigrated from Albania. Aliu writes a story of love, family, and the search for an origin story, set against the decaying backdrop of a post-industrial town. In a starred review, Kirkus writes "Aliu’s riveting, sensitive work shines with warmth, clarity, and a generosity of spirit." (Lydia)

The Immortalists by Chloe Benjamin: Four adolescent sibling in 1960s New York City sneak out to see a psychic, who tells each of them the exact date they will die. They take this information with a grain of salt, and keep it from each other, but Benjamin’s novel follows them through the succeeding decades, as their lives alternately intertwine and drift apart, examining how the possible knowledge of their impending death affects how they live. I’m going to break my no-novels-about-New-Yorkers rule for this one. (Janet)

King Zeno by Nathaniel Rich: This historical thriller features an ax-wielding psychopath wreaking havoc in the city of Sazeracs. It’s been eight years since Rich moved to New Orleans, and in that time, he’s been a keen observer, filing pieces on the city’s storied history and changing identity for various publications, not least of all The New York Review of Books. He’s certainly paid his dues, which is vitally important since the Big Easy is an historically difficult city for outsiders to nail without resorting to distracting tokenism (a pelican ate my beignet in the Ninth Ward). Fortunately, Rich is better than that. (Nick M.)

The Monk of Mokha by Dave Eggers: Eggers returns to his person-centered reportage with an account of a Yemeni-American man named Mokhtar Alkhanshali's efforts to revive the Yemeni tradition of coffee production just when war is brewing. A starred Kirkus review calls Eggers's latest "a most improbable and uplifting success story." (Lydia)

In Every Moment We Are Still Alive by Tom Malmquist (translated by Henning Koch): A hit novel by a Swedish poet brought to English-reading audiences by Melville House. This autobiographical novel tells the story of a poet whose girlfriend leaves the world just as their daughter is coming into it--succumbing suddenly to undiagnosed leukemia at 33 weeks. A work of autofiction about grief and survival that Publisher's Weekly calls a "beautiful, raw meditation on earth-shattering personal loss." (Lydia)

Peculiar Ground by Lucy Hughes-Hallett: The award-winning British historian (The Pike: Gabriele D'Annunzio, Poet, Seducer and Preacher of War) makes her fiction debut. Narrated by multiple characters, the historical novel spans three centuries and explores the very timely theme of immigration. Walls are erected and cause unforeseen consequences for both the present and futurey. In its starred review, Kirkus said the novel was "stunning for both its historical sweep and its elegant prose." (Carolyn)

Neon in Daylight by Hermione Hoby: A novel about art, loneliness, sex, and restless city life set against the backdrop of Hurricane Sandy-era New York, Neon in Daylight follows a young, adrift English catsitter as she explores the galleries of New York and develops an infatuation with a successful writer and his daughter, a barista and sex-worker. The great Ann Patchett called Hoby "a writer of extreme intelligence, insight, style and beauty." (Lydia)

This Could Hurt by Jillian Medoff: Medoff works a double shift: when she isn’t writing novels, she’s working as a management consultant, which means, as her official bio explains, “that she uses phrases like ‘driving behavior’ and ‘increasing ROI’ without irony.” In her fourth novel, she turns her attention to a milieu she knows very well, the strange and singular world of corporate America: five colleagues in a corporate HR department struggle to find their footing amidst the upheaval and uncertainty of the 2008-2009 economic collapse. (Emily)

The Afterlives by Thomas Pierce: Pierce’s first novel is a fascinating and beautifully rendered meditation on ghosts, technology, marriage, and the afterlife. In a near-future world where holograms are beginning to proliferate in every aspect of daily life, a man dies—for a few minutes, from a heart attack, before he’s revived—returns with no memory of his time away, and becomes obsessed with mortality and the afterlife. In a world increasingly populated by holograms, what does it mean to “see a ghost?” What if there’s no afterlife? On the other hand, what if there is an afterlife, and what if the afterlife has an afterlife? (Emily)

Grist Mill Road by Christopher J. Yates: The follow-up novel by the author of Black Chalk, an NPR Best of the Year selection. Yates's latest "Rashomon-style" literary thriller follows a group of friends up the Hudson, where they are involved in a terrible crime. "I Know What You Did Last Summer"-style, they reconvene years later, with dire consequences. The novel receives the coveted Tana French endorsement: she calls it "darkly, intricately layered, full of pitfalls and switchbacks, smart and funny and moving and merciless." (Lydia)

FEBRUARY

The Friend by Sigrid Nunez: In her latest novel, Nunez (a Year in Reading alum) ruminates on loss, art, and the unlikely—but necessary—bonds between man and dog. After the suicide of her best friend and mentor, an unnamed, middle-aged writing professor is left Apollo, his beloved, aging Great Dane. Publishers Weekly says the “elegant novel” reflects “the way that, especially in grief, the past is often more vibrant than the present.” (Carolyn)

Feel Free by Zadie Smith: In her forthcoming essay collection, Smith provides a critical look at contemporary topics, including art, film, politics, and pop-culture. Feel Free includes many essays previously published in The New Yorker and The New York Review of Books and it is divided into five sections: In the World, In the Audience, In the Gallery, On the Bookshelf, and Feel Free. Andrew Solomon described the collection as “a tonic that will help the reader reengage with life.” (Zoë)

What Are We Doing Here? by Marilynne Robinson: One of my favorite literary discoveries of 2017 was that there are two camps of Robinson fans. Are you more Housekeeping or Gilead? To be clear, all of us Housekeeping people claim to have loved her work before the Pulitzer committee agreed. But this new book is a collection of essays where Robinson explores the modern political climate and the mysteries of faith, including, "theological, political, and contemporary themes." Given that the essays come from Robinson's incisive mind, I think there will be more than enough to keep both camps happy. (Claire)

An American Marriage by Tayari Jones: In our greatest tragedies, there is the feeling of no escape—and when the storytelling is just right, we feel consumed by the heartbreak. In Jones’s powerful new novel, Celestial and Roy are a married couple with optimism for their future. Early in the book, Jones offers a revelation about Roy’s family, but that secret is nothing compared to what happens next: Roy is arrested for a crime he didn’t commit, and sentenced to over a decade in prison. An American Marriage arrives in the pained, authentic voices of Celestial, Roy, and Andre—Celestial’s longtime friend who moves into the space left by Roy’s absence. Life, and love, must go on. When the couple writes “I am innocent” to each other in consecutive letters, we weep for their world—but Jones makes sure that we can’t look away. (Nick R.)

The Strange Bird by Jeff VanderMeer: Nothing is what it seems in VanderMeer’s fiction: bears fly, lab-generated protoplasm shapeshifts, and magic undoes science. In this expansion of his acclaimed novel Borne, which largely focused on terrestrial creatures scavenging a post-collapse wasteland, VanderMeer turns his attention upward. Up in the sky, things look a bit different. (Check out his prodigious Year in Reading here.) (Nick M.)

House of Impossible Beauties by Joseph Cassara: First made famous in the documentary Paris Is Burning, New York City’s House of Xtravaganza is now getting a literary treatment in Cassara’s debut novel—one that’s already drawing comparisons to Hanya Yanagihara’s A Little Life. The story follows teenage Angel, a young drag queen just coming into her own, as she falls in love, founds her own house and becomes the center of a vibrant—and troubled—community. Critics call it “fierce, tender, and heartbreaking.” (Kaulie)

Freshwater by Akwaeke Emezi: A surreal, metaphysical debut novel dealing with myth, mental health, and fractured selves centering around Ada, a woman from southern Nigeria "born with one foot on the other side." She attends college in the U.S., where several internal voices emerge to pull her this way and that. Library Journal calls this "a gorgeous, unsettling look into the human psyche." (Lydia)

Red Clocks by Leni Zumas: The latest novel from the author of The Listeners follows five women of different station in a small town in Oregon in a U.S. where abortion and IVF have been banned and embryos have been endowed with all the rights of people. A glimpse at the world some of our current lawmakers would like to usher in, one that Maggie Nelson calls "mordant, political, poetic, alarming, and inspiring--not to mention a way forward for fiction now." (Lydia)

Heart Berries by Terese Mailhot: In her debut memoir, Mailhot—raised on the Seabird Island Indian Reservation in southwestern Canada, presently a postdoctoral fellow at Purdue—grapples with a dual diagnosis of PTSD and Bipolar II disorder, and with the complicated legacy of a dysfunctional family. Sherman Alexie has hailed this book as “an epic take—an Iliad for the indigenous.” (Emily)

Asymmetry by Lisa Halliday: 2017 Whiting Award winner Halliday has written a novel interweaving the lives of a young American editor and a Kurdistan-bound Iraqi-American man stuck in an immigration holding room in Heathrow airport. Louise Erdrich calls this "a novel of deceptive lightness and a sort of melancholy joy." (Lydia)

Back Talk by Danielle Lazarin: long live the short story, as long as writers like Lazarin are here to keep the form fresh. The collection begins with “Appetite,” narrated by nearly 16-year-old Claudia, whose mother died of lung cancer. She might seem all grown up, but “I am still afraid of pain—for myself, for all of us.” Lazarin brings us back to a time when story collections were adventures in radical empathy: discrete panels of pained lives, of which we are offered chiseled glimpses. Even in swift tales like “Window Guards,” Lazarin has a finely-tuned sense of pacing and presence: “The first time Owen shows me the photograph of the ghost dog, I don’t believe it.” Short stories are like sideways glances or overheard whispers that become more, and Lazarin makes us believe there’s worth in stories that we can steal moments to experience. (Nick R.)

The Château by Paul Goldberg: In Goldberg’s debut novel, The Yid, the irrepressible members of a Yiddish acting troupe stage manages a plot to assassinate Joseph Stalin in hopes of averting a deadly Jewish pogrom. In his second novel, the stakes are somewhat lower: a heated election for control of a Florida condo board. Kirkus writes that Goldberg’s latest “confirms his status as one of Jewish fiction's liveliest new voices, walking in the shoes of such deadpan provocateurs as Mordecai Richler and Stanley Elkin.” (Matt)

The Line Becomes a River by Francisco Cantú: A memoir by a Whiting Award-winner who served as a U.S. border patrol agent. Descended from Mexican immigrants, Cantú spends four years in the border patrol before leaving for civilian life. His book documents his work at the border, and his subsequent quest to discover what happened to a vanished immigrant friend. (Lydia)

Call Me Zebra by Azareen Van der Vliet Oloomi: If the driving force of Van der Vliet Oloomi's first novel, Fra Keeler, was "pushing narrative to its limits" through unbuilding and decomposition, her second novel, Call Me Zebra, promises to do the same through a madcap and darkly humorous journey of retracing the past to build anew. Bibi Abbas Abbas Hossein is last in a line of autodidacts, anarchists, and atheists, whose family left Iran by way of Spain when she was a child. The book follows Bibi in present day as she returns to Barcelona from the U.S., renames herself Zebra and falls in love. Van der Vliet Oloomi pays homage to a quixotic mix of influences—including Miguel de Cervantes, Jorge Luis Borges, and Kathy Acker—in Call Me Zebra, which Kirkus calls "a brilliant, demented, and bizarro book that demands and rewards all the attention a reader might dare to give it." (Anne)

Some Hell by Patrick Nathan: A man commits suicide, leaving his wife, daughter, and two sons reckoning with their loss. Focused on the twinned narratives of Colin, a middle schooler coming to terms with his sexuality, as well as Diane, his mother who’s trying to mend her fractured family, Nathan’s debut novel explores the various ways we cope with maturity, parenting, and heartbreak. (Read Nathan's Year in Reading here.) (Nick M.)

The Wedding Date by Jasmine Guillory: If 2017 was any indication, events in 2018 will try the soul. Some readers like to find escape from uncertain times with dour dystopian prognostications or strained family stories (and there are plenty). But what about something fun? Something with sex (and maybe, eventually, love). Something Roxane Gay called a "charming, warm, sexy gem of a novel....One of the best books I've read in a while." Something so fun and sexy it earned its author a two-book deal (look out for the next book, The Proposal, this fall). Wouldn't it feel good to feel good again? (Lydia)

MARCH

The Census by Jesse Ball: Novelist Ball's nimble writing embodies the lightness and quickness that Calvino prized (quite literally, too: he pens his novels in a mad dash of days to weeks). And he is prolific, too. Since his previous novel, How to Start a Fire and Why, he has has written about the practice of lucid dreaming and his unique form of pedagogy, as well as a delightfully morbid compendium of Henry King’s deaths, with Brian Evenson. Ball's seventh novel, The Census, tells the story of a dying doctor and his concern regarding who will care for his son with Down Syndrome, as they set off together on a cross-country journey. (Anne)

Men and Apparitions by Lynne Tillman: News of a new Tillman novel is worthy of raising a glass. Men and Apparitions is the follow-up novel to Tillman's brilliant, ambitious American Genius: A Comedy. Men and Apparitions looks closely at our obsession with the image through the perspective of cultural anthropologist Ezekiel "Zeke" Hooper Stark. Norman Rush says, "this book is compelling and bracing and you read many sentences twice to get all the juice there is in them.” Sarah Manguso has said she is "grateful" for Tillman's "authentically weird and often indescribable books." I second that. (Anne)

Whiskey & Ribbons by Leesa Cross-Smith: Police officer Eamon Michael Royce is killed in the line of duty. His pregnant wife, Evi, narrates Eamon’s passing with elegiac words: “I think of him making the drive, the gentle peachy July morning light illuminating his last moments, his last heartbeat, his last breath.” Months later and wracked with grief, Evi falls for her brother-in-law Dalton: “Backyard-wandering, full-moon pregnant in my turquoise maternity dress and tobacco-colored cowboy boots. I’d lose my way. Dalton would find me. He was always finding me.” The sentences in Cross-Smith’s moving debut are lifted by a sense of awe and mystery—a style attuned to the graces of this world. Whiskey & Ribbons turns backward and forward in time: we hear Eamon’s anxieties about fatherhood, and Dalton’s continuous search for meaning in his life. “I am always hot, like I’m on fire,” Evi dreams later in the novel, still reliving her husband’s death, “burning and gasping for air.” In Cross-Smith’s novel, the past is never forgotten. (Nick R.)

The Emissary by Yoko Tawada (translated by Margaret Mitsutani): In a New Yorker essay on Tawada, author of Memoirs of a Polar Bear, Riva Galchen wrote that “often in [her] work, one has the feeling of having wandered into a mythology that is not one’s own.” Tawada’s latest disorienting mythology is set in a Japan ravaged by a catastrophe. If children are the future, what does it presage that, post-disaster, they are emerging from the womb as frail, aged creatures blessed with an uncanny wisdom? (Read her Year in Reading here.) (Matt)

The Sparsholt Affair by Alan Hollinghurst: Hollinghurst’s sixth novel has already received glowing reviews in the U.K. As the title suggests, the plot hinges on a love affair, and follows two generations of the Sparsholt family, opening in 1940 at Oxford, just before WWII. The Guardian called it “an unashamedly readable novel...indeed it feels occasionally like Hollinghurst is trying to house all the successful elements of his previous books under the roof of one novel.” To those of us who adore his books, this sounds heavenly. (Hannah)

The Chandelier by Clarice Lispector (translated by Magdalena Edwards and Benjamin Moser): Since Katrina Dodson published a translation of Lispector’s complete stories in 2015, the Brazilian master's popularity has enjoyed a resurgence. Magdalena Edwards and Benjamin Moser’s new translation of Lispector’s second novel promises to extend interest in the deceased writer’s work. It tells the story of Virginia, a sculptor who crafts intricate pieces in marked isolation. This translation marks the first time The Chandelier has ever appeared in English (Ismail).

The Parking Lot Attendant by Nafkote Tamirat: It's very easy to love this novel but difficult to describe it. A disarming narrator begins her account from a community with strange rules and obscure ideology located on an unnamed island. While she and her father uneasily bide their time in this not-quite-utopia, she reflects on her upbringing in Boston, and a friendship--with the self-styled leader of the city's community of Ethiopian immigrants--that begins to feel sinister. As the story unfolds, what initially looked like a growing-up story in a semi-comic key becomes a troubling allegory of self-determination and sacrifice. (Lydia)

Let's No One Get Hurt by Jon Pineda: A fifteen-year-old girl named Pearl lives in squalor in a southern swamp with her father and two other men, scavenging for food and getting by any way they can. She meets a rich neighbor boy and starts a relationship, eventually learning that his family holds Pearl's fate in their hands. Publisher's Weekly called it "an evocative novel about the cruelty of children and the costs of poverty in the contemporary South." (Lydia)

The Merry Spinster by Mallory Ortberg: Fairy tales get a feminist spin in this short story collection inspired by Ortberg's most popular Toast column, "Children's Stories Made Horrific." This is not your childhood Cinderella, but one with psychological horror and Ortberg's signature snark. Carmen Maria Machado calls it a cross between, "Terry Pratchett’s satirical jocularity and Angela Carter’s sinister, shrewd storytelling, and the result is gorgeous, unsettling, splenic, cruel, and wickedly smart." Can't wait to ruin our favorite fables! (Tess)

The House of Broken Angels by Luis Alberto Urrea: Urrea is one of the best public speakers I’ve ever seen with my 35-year-old eyes, so it’s incredible that it’s not even the thing he’s best at. He’s the recipient of an American Book Award and a Pulitzer nominee for The Devil’s Highway. His new novel is about the daily life of a multi-generational Mexican-American family in California. Or as he puts it, “an American family—one that happens to speak Spanish and admire the Virgin of Guadalupe.” (Janet)

Speak No Evil by Uzodinma Iweala: Nearly 15 years after his critically-acclaimed debut novel, Beasts of No Nation, was published, Iweala is back with a story as deeply troubling. Teenagers Niru and Meredith are best friends who come from very different backgrounds. When Niru’s secret is accidentally revealed (he’s queer), there is unimaginable and unspeakable consequences for both teens. Publishers Weekly’s starred review says the “staggering sophomore novel” is “notable both for the raw force of Iweala’s prose and the moving, powerful story.” (Carolyn)

American Histories: Stories by John Edgar Wideman: Wideman’s new book is a nearly fantastical stretching and blurring of conventional literary forms—including history, fiction, philosophy, biography, and deeply felt personal vignettes. We get reimagined conversations between the abolitionist Frederick Douglass and the doomed white crusader for racial equality John Brown. We get to crawl inside the mind of a man sitting on the Williamsburg Bridge, ready to jump. We get Wideman pondering deaths in his own family. We meet Jean Michel Basquiat and Nat Turner. What we get, in the end, is a book unlike any other, the work of an American master working at peak form late in a long and magnificent career. (Bill)

Happiness by Aminatta Forna: A novel about what happens when an expert on the habits of foxes and an expert on the trauma of refugees meet in London, one that Paul Yoon raved about it in his Year in Reading: "It is a novel that carries a tremendous sense of the world, where I looked up upon finishing and sensed a shift in what I thought I knew, what I wanted to know. What a gift." In a starred review, Publisher's Weekly says "Forna's latest explores instinct, resilience, and the complexity of human coexistence, reaffirming her reputation for exceptional ability and perspective." (Lydia)