“It is easy to see the beginnings of things, and harder to see the ends.” –Joan Didion

1.

It becomes palpable in late spring, when I receive a pair of unconditional offers posted first-class Royal Mail. I give ample notice at work; I make a little list of things I “haven’t done yet,” as though I am permanently relocating to the moon and will never again have the opportunity to ride the Staten Island Ferry; I chart out the furniture I need to sell, making guesses at how much cash I might collect as I disassemble my life. The days slip by and summer stutters in, blisteringly hot at first, then endless weeks of rain. (Half a dozen people say something to the effect of “You’d better get used to this!” often with a wink and a nudge, and I bite my tongue, or sometimes, I don’t, and snap, “The rain in England is not like this,” even though sometimes it actually is. A friend buys me a raincoat — a “parting gift” for the “the precipitation zone you will be heading to” — and I am profoundly grateful.) I begin to get maudlin as I leave certain places, or say goodbye to people at the end of the night. “Will this be the last time I…” The abstract idea that has hovered over me for ages — leaving New York City — sprouts legs and begins to crawl.

I’m headed to University College London in the fall, after one more season taking bets in my hometown, at the Saratoga Racecourse (this summer marks my tenth anniversary as a pari-mutuel clerk). These steps have been charted for a good while now, guided by the gravitational pull of London, a city in which I’ve lived before and a place that always manages to provoke my most extreme emotions, for better or for worse. Before all of that, though, I have to say goodbye to New York, which feels a bit self-indulgent: people change cities, migrate across the globe, uproot their lives every day, and most of them don’t feel compelled to write long essays about moving. But New York, though — maybe it’s the preponderance of writers here, the narcissism and the navel-gazing, that turns our comings and goings into a series of extended metaphors? We document our arrivals and our acclimations, the natural evolution of a human being, growing older — changing in a city that’s often painted as the living embodiment of change. And when we manage to leave, if we manage to leave, escape becomes a genre in and of itself.

Because it often feels like that: escape, like getting out of town is risky, or hard to coordinate, or something that happens just in the nick of time. There are a lot of “leaving New York essays” out there, nearly all of them framed from the vantage of the author’s new location, a place that’s usually less shiny or less gritty, somewhere that’s better in a lot of ways but invariably shadowed by nostalgic regret, maybe a kind of lingering sense of not having “made it” here, whatever that means. They follow a tested formula: you march confidently across the Hudson possessed with extreme naivety, because you are impossibly young when you arrive in New York, no matter your age on paper; you quickly learn the same sorts of hard lessons that people have learned for years on end; you pay a lot and get very little and sharpen your cockroach-killing reflexes; you have moments of startling clarity, as you reference specific street corners or landmarks or bits of cultural currency, paired with embarrassing vocalizations of these moments of clarity. (These references have obviously shifted over the years; right now, it’s often people drinking Tecate on rooftops in Bushwick as the sun sets over the Midtown skyline. For me, in my years working the night shift in a skyscraper in Times Square, it was the Midtown skyline sometime after midnight, from the BQE just above the Kosciuszko Bridge, cemeteries and hulking warehouses shadowed in the foreground and a postcard stretch of light and geometric wonder across the river.)

And then somewhere along the way, it ends. It’s not the day you leave, because if you’re writing this sort of piece, it’s likely that no one is forcing you to go, or you’re not putting up much of a fight. The New York of our imaginations has to end sooner than that — maybe it collapses under the weight of our own preconceptions, or maybe pinning so much responsibility on a city serves to mask the way the passage of time can alter us: when we arrive we are willing and eager to fold ourselves into different shapes, to make ourselves fit, but as we grow older, acts of contortion become more difficult, or at the very least, less desirable. It was always easy enough for me to live here, but my New York lost the vibrancy of the early days pretty quickly; I could hold my folded shape, but the stagnancy chipped away at me over time. People say that New York is a city for the rich, or a city for the young; it is also a city for the new and the bendable.

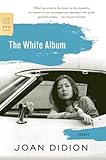

On Easter Sunday, I box up my books and hesitate as my fingers pass over a well-worn pair of Didion essay collections, the big two, Slouching Towards Bethlehem and The White Album. I am sorting books into three piles: to give away; to send upstate; and to keep around for my final few months in New York, things I know I need to read, my half-dozen favorites, and a few shelves of “emergency books” that I irrationally feel like I might want to reference and need nearby me at all times. Afterwards it looks like the oddest little library — Gulliver’s Travels and Orwell’s essays and Evelyn Waugh’s collected short stories? Why did I keep these things here? Did I think I’d need to peruse How Fiction Works in a pinch? But I remember now, three months later, why I kept the Didions close at hand. In the vast realm of “leaving New York” essays, “Goodbye to All That” says everything that has ever needed to be said — but better.

On Easter Sunday, I box up my books and hesitate as my fingers pass over a well-worn pair of Didion essay collections, the big two, Slouching Towards Bethlehem and The White Album. I am sorting books into three piles: to give away; to send upstate; and to keep around for my final few months in New York, things I know I need to read, my half-dozen favorites, and a few shelves of “emergency books” that I irrationally feel like I might want to reference and need nearby me at all times. Afterwards it looks like the oddest little library — Gulliver’s Travels and Orwell’s essays and Evelyn Waugh’s collected short stories? Why did I keep these things here? Did I think I’d need to peruse How Fiction Works in a pinch? But I remember now, three months later, why I kept the Didions close at hand. In the vast realm of “leaving New York” essays, “Goodbye to All That” says everything that has ever needed to be said — but better.

2.

I bought Slouching Towards Bethlehem in the final weeks of my senior year of college, and I read it during the strange, torpid months that followed. I open it up years later and remember, with some surprise, that those months coincided with my ill-fated experiment in becoming the kind of person who makes notations in books. Flipping through the essays, I see that I was playing fast and loose with the brackets and asterisks, basically rendering the act of marking totally pointless, like highlighting an entire page. I marked some good stuff, but most of it’s good stuff, kind of extraordinary stuff, really. It’s here that I should pause and acknowledge that if there’s anything more tedious than a “leaving New York” essay, it’s a “young girl discovers that Joan Didion has an inside window into her soul” essay. Bear with me for a moment, please.

I can’t help but wonder why “Goodbye to All That” was placed at the very end of the book: chronologically, it belongs at the very beginning — it explains away her twenties, and lays some of the foundations for the woman we find through all the rest, simultaneously fragile and steely, searching for answers under the California sun. Didion in New York is bendable to the point of breaking: it feels so removed from the rest of it, and I suppose, in a real sense, it was: she arrived here at age twenty, in the late fifties; she left eight years later, to return to her native California, as the West Coast was securing its central place in the socio-political history of the decade, and a permanent place in the American cultural imagination. In the final pages of the book we do a bit of a 180, back to Didion’s New York. Even from a distance, across the river and half a century later, the city is so instantly recognizable that it’s startling. I re-read the part about talking to her long-distance boyfriend during the first few days and laugh aloud on a packed train at rush hour. (“I would stay in New York, I told him, just six months, and I could see the Brooklyn Bridge from my window. As it turned out the bridge was the Triborough, and I stayed eight years.”)

There’s a dangerous paradox in writing about your earliest years, about the very beginnings of adulthood. We believe our experiences to be unique but the messages to be universal, and we have a hell of a time trying to strike the right balance, without coming off as narcissistic or arrogant, qualities that look all the harsher when paired with inexperience and immaturity. It’s tricky to avoid whining. The circumstances of my own first year out of school are difficult to quantify, sometimes interesting, sometimes mind-numbingly ordinary: the post-graduation confusion, then a return to my summer job at the track; moving to Edinburgh to work in a t-shirt shop and live in a long-term hostel; moving to San Francisco to take an internship and cobble together rent money with sketchy side gigs; getting a call one day in early July, waiting for cheap sushi in San Francisco’s financial district, that my best friend had been hit by a truck and killed as she was biking to work that morning. I had decided to leave California a few weeks prior; I felt slightly out-of-synch out west, uncomfortable in ways I’d never felt in Scotland, as grim as my life there turned out to be. With loss, priorities can sharpen. I returned east immediately.

If you asked me to explain myself that year, I’m not sure I could. I can outline my movements in plane tickets and bank statements, in e-mail chains and hazily-recalled phone conversations, but I fall victim to that paradox, the simultaneous convictions of uniqueness and universality. I came to New York on the heels of all of this, and those convictions solidified there, as I attempted to lay the foundations of the life I felt I was supposed to lead. Didion describes her own naïve march into New York by addressing the paradox with a kind of unflinching sentimentality:

When I first saw New York I was twenty, and it was summertime, and I got off a DC-7 at the old Idlewild temporary terminal in a new dress which had seemed very smart in Sacramento but seemed less smart already, even in the old Idlewild temporary terminal, and the warm air smelled of mildew and some instinct, programmed by all the movies I had ever seen and all the songs I had ever heard sung and all the stories I had ever read about New York, informed me that it would never be quite the same again. In fact, it never was. Some time later there was a song on all the jukeboxes on the upper East Side that went “but where is the schoolgirl who used to be me,” and if it was late enough at night I used to wonder that. I know now that almost everyone wonders something like that, sooner or later and no matter what he or she is doing, but one of the mixed blessings of being twenty and twenty-one and even twenty-three is the conviction that nothing like this, all evidence to the contrary notwithstanding, has ever happened to anyone before.

It almost feels like some sleight-of-hand, the way the experiences her twenty-year-old self believes to be singular are cut down by that final sentence. Didion, a pioneer in the school of New Journalism, stretches her years in New York across the city like a broad, welcoming umbrella, inviting all of us underneath to find our own experiences in her early fumblings. “Of course it might have been some other city,” she writes, “had circumstances been different and the time been different and had I been different, might have been Paris or Chicago or even San Francisco, but because I am talking about myself I am talking here about New York.” I can’t help but wonder, though; it’s an impossible sentence to counter, after all. I compare my own earliest fumblings to my years in New York — the place where my twenties slipped away, where I worked very hard and got just a little bit in return, where I spent huge swathes of time never setting foot outside the five boroughs (more like three boroughs, actually), where my own cultural assumptions met up with hard realities, where I stopped to marvel at that stretch of the Midtown skyline every single time I passed it — and I think that it couldn’t have been anywhere else. But then, perhaps because I am talking about myself I am talking here about New York.

3.

Everything changes, even people, at least a little bit, and I watched my friends unravel somewhat in New York and then weave themselves into something nearly unrecognizable to me. I am leaving at a pivotal moment: one after another, people I know bid goodbye to their twenties, approaching the time when it feels as though one must choose to escape New York and rebuild elsewhere, or attempt to graduate into a more settled existence, moving in with partners and purchasing real estate and thinking about the future in years, maybe decades, rather than months. I think that those who stay are not choosing the life I’ve known: they are hoping to create something new, or so I assume. All the while, the circle contracts: a good number of my friends, some of the closest, have left town within the past year or two, nearly all of them in the height of summer, making toasts at outdoor goodbye parties as sweat collects at the backs of our knees.

I want to say goodbye properly but I am not quite sure how to manage it. “You’ll be back,” people tell me, at work or out at some party or other, and I think, well, maybe, or better yet: yes and no. Joan Didion, after all, has returned to the Upper East Side. I can come back for certain — though maybe when I win the lottery, because I can barely afford to stay now — but I can’t return to any of this; I lost it some time ago. I suppose that’s why it’s so much easier to say goodbye to the physical space, to the things that give me my daily bearings, than to the alternative: I’ve always been terrible at endings, from my childhood notebooks to the current collection of folders on my desktop littered with unfinished stories and essays, things that are very nearly there, if only I could find the last key piece, some subtle thematic note that could tie it all together.

“Goodbye to All That” takes its title from Robert Graves’s autobiography, Good-Bye to All That, his “bitter leave-taking of England” written in the wake of the First World War. But Didion’s essay, first published in The Saturday Evening Post, was originally titled “Farewell to the Enchanted City,” which I think might suit it better, in some inexplicable way. There’s so much inevitable disappointment wrapped up in the title — nostalgic regret, my absolute go-to when leaving a place. The Enchanted City, the land of outsized expectations. “All I mean is that I was very young in New York, and that at some point the golden rhythm was broken, and I am not that young anymore.” It isn’t hard to live here, for some of us, but maybe it is hard to sort our expectations from our dreams: the horizon is too hazy, blotted out by the skyline.

“Goodbye to All That” takes its title from Robert Graves’s autobiography, Good-Bye to All That, his “bitter leave-taking of England” written in the wake of the First World War. But Didion’s essay, first published in The Saturday Evening Post, was originally titled “Farewell to the Enchanted City,” which I think might suit it better, in some inexplicable way. There’s so much inevitable disappointment wrapped up in the title — nostalgic regret, my absolute go-to when leaving a place. The Enchanted City, the land of outsized expectations. “All I mean is that I was very young in New York, and that at some point the golden rhythm was broken, and I am not that young anymore.” It isn’t hard to live here, for some of us, but maybe it is hard to sort our expectations from our dreams: the horizon is too hazy, blotted out by the skyline.

Months to go, then weeks, and then it is a matter of days. I take stock, and I don’t say much, let alone any real goodbyes. To the physical spaces, my favorite corners: Cadman Plaza just after a thunderstorm, the view up Manhattan Avenue, dashing towards the train at Bryant Park at sunset. To the golden rhythms of the life I’ve known, because I, like Didion, spent my New York years making a magazine: I spend a few weeks working to not feel responsible for these words on these pages, for the publication to whom I’ve sacrificed Friday nights for nearly five years (and a good number of Saturdays, too), for the magazine that’s always been irrevocably wrapped up in my idea of New York, long before I ever stepped foot in the lobby. To my friends, who, if we can manage it, will always be my friends, but never like this again — even if I rushed back tomorrow, the ground has already shifted beneath me. But mostly to the Enchanted City, to the idea of it, how effortlessly it formed in my mind, and how it can disappear in an instant, when your back is turned. Someone else, somewhere, is arriving right now, marching across the Hudson: picking it back up, and falling in love with New York City for the first time, too.

Image Credit: pexels/Arthur Brognoli.