Despite its growing popularity among Anglophone readers, the crónica—a unique form of literary reportage that blurs the lines of fact and fiction—remains a quintessentially Latin American genre. In English, scant studies on the form exist beyond 2002’s The Contemporary Mexican Chronicle. The genre has long been marked by its political, polemical overtones (Rodolfo Walsh’s Operation Massacre, for example), but increasing democratization across Latin American has seen it shift toward a lighter, more observational approach, in which the writer keeps their distance (as in Fernanda Melchor’s This Is Not Miami.)

Despite its growing popularity among Anglophone readers, the crónica—a unique form of literary reportage that blurs the lines of fact and fiction—remains a quintessentially Latin American genre. In English, scant studies on the form exist beyond 2002’s The Contemporary Mexican Chronicle. The genre has long been marked by its political, polemical overtones (Rodolfo Walsh’s Operation Massacre, for example), but increasing democratization across Latin American has seen it shift toward a lighter, more observational approach, in which the writer keeps their distance (as in Fernanda Melchor’s This Is Not Miami.)

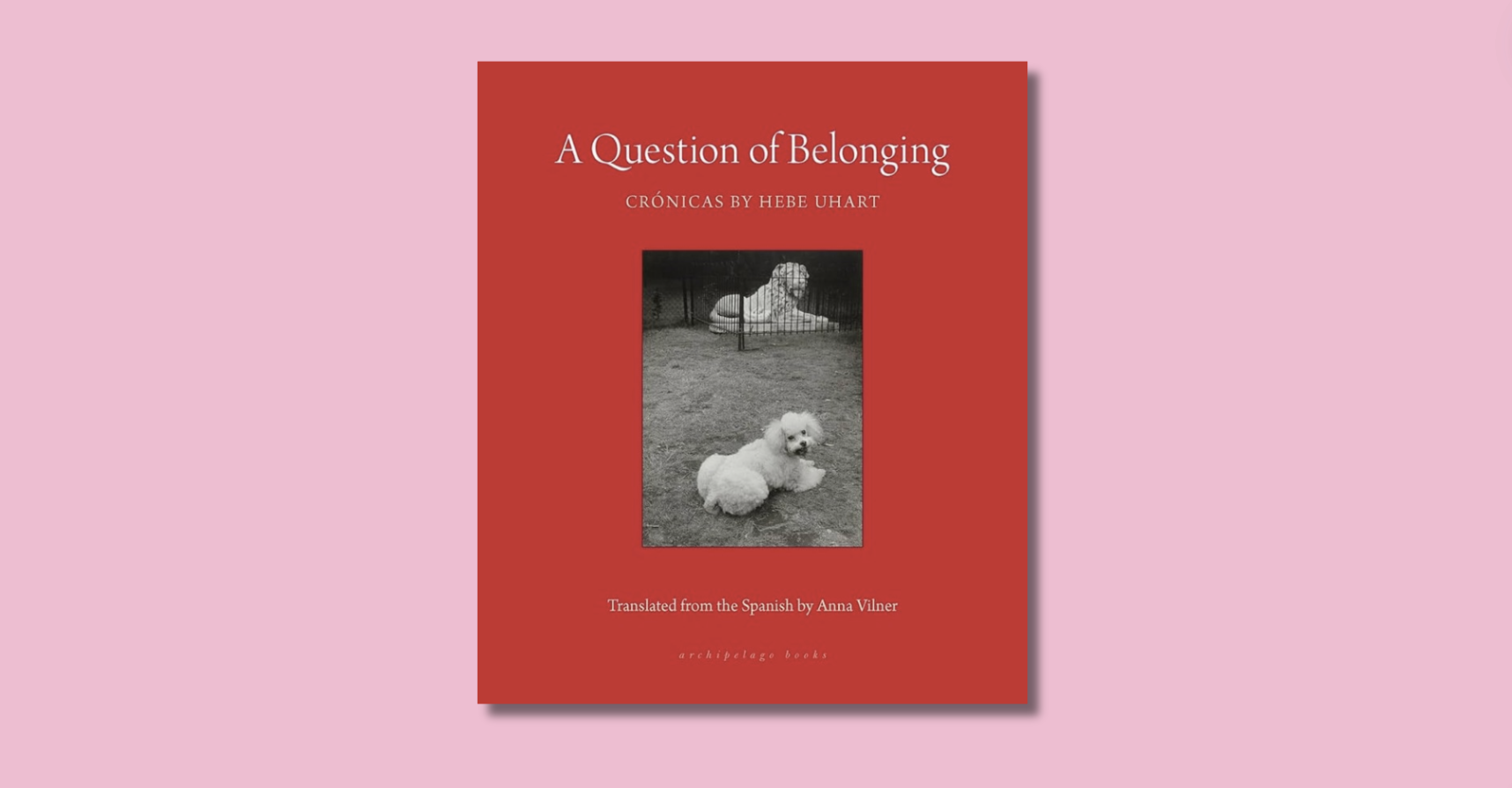

Toward the end of her life, the late Argentine writer Hebe Uhart—known for her novels, short stories, and travel logs—almost exclusively wrote crónicas. She turned to the form because “she felt that what the world had to offer was more interesting than her own experience or imagination,” writes Mariana Enriquez in the introduction to A Question of Belonging, a collection 25 of Uhart’s crónicas that probe her daily life and travels across Latin America. Enriquez’s statement gives some insight into the central tenets that bind these stories: despite drawing on her own experiences, Uhart keeps autobiographical intrusions to a minimum. A Question of Belonging, translated by Anna Vilner, is also marked by an unerring belief that a good story can be found almost anywhere. As Alejandra Costamagna put it in a 2019 essay, Uhart’s stories capture a “reality interrupted by strangeness.”

Crónicas tend to track how a situation is perceived, rather than the situation itself. They are concerned with how a person, or persons, look at things. As the writer Javier Sinay noted in a recent interview, in Spanish the word mirada—a look, a gaze—is often used to describe the genre. Uhart is often noted for her unique way of looking, characterized by restless curiosity as well as an almost childlike sense of awe. In the story “Good Manners,” she finds herself in a typically banal situation: riding on a bus. She tries to join in on a conversation between an elderly woman and the bus driver. She is giddy—“it isn’t every day that a bus driver speaks”—though ultimately fails to worm her way in; the impossible rules of “good manners” are at play, and she keeps inadvertently breaking them:

Her silence made me feel like I was six or seven years old again, playing with a nutty girl I knew: every time I went to do something […] the girl would stomp her foot angrily and say “No!”. It made me feel like I was perpetually in the wrong.

Indeed, through the eyes of a child, these sorts of routines and habits prove impenetrable. As social norms are fogged by inexperience, she is left confused, capable only of interpreting these behaviors in the context of children at play. At the same time, by filtering the world through childish instincts, a stubborn sense of wonder and merriment emerges.

Despite a love for the domestic and ordinary, Uhart is also drawn to the exceptional, the strange, and the surreal. In “Fabricio,” Uhart describes a man “who belongs to space, not time. […] He believed that if he stayed in the same place for too long he would deteriorate and shrink up.” She goes onto lay out his various neuroses: he rarely uses furniture for its designed function—a fridge turned on its side becomes a desk, “a curtain or bedspread as a little roof to block the sun.” While the premise is intriguing, it is over and done with in just three brief pages, and by the end you are left imagining Uhart is simply recounting a story she overheard in a café or at a bus stop, more or less verbatim. Perhaps the story of Fabricio is a little too obvious for her taste; his eccentricity is so clear right off the bat that it doesn’t pose much of a challenge to her or her readers. The metaphysical anomalies that Uhart prefers are more subtle, and usually require her to travel to alien, unfrequented lands.

Uhart’s incentives for travel are unordinary to say the least. In the middle of January, while most Porteños are holidaying far away, Uhart sets off for Tapalqué—a small Buenos Aires town with a population of 6,000—“without any contacts, guided by some higher power.” She goes following a friends tip that Tapalqué was known for its unique sayings and idioms: “the town creates its own refrains.” At the center of Uhart’s project is a desire to understand people different from herself, and she knows that explicitly asking isn’t always a surefire route to knowledge. That’s why she’s particularly interested in figures of speech as a path to learning about another culture—the way they can unearth what would might otherwise have remained hidden.

As she discovers, Tapalqué sayings incorporate criollo wisdom, which “point to the intimate relationship between animal and human behavior.” For example, “when someone is not typically prone to insight or subtlety says something interesting, they say ‘My dog caught a fly.” Other idioms reveal the diplomacy and compassion at the heart of the culture. “They are not ones for direct reproaches or quick value judgements,” Uhart writes. “Instead of saying […] ‘you’re wrong,’ a softer alternative might be: “It seems to me, Roldán, that not all of these cows are yours.”

While Uhart is dogged in her pursuit of strangeness and understanding, she doesn’t always succeed when it comes to the latter. In “Off to Mexico,” Uhart sets off to Guadalajara and Mexico City for an international book fair. And while she has her idiosyncratic goals, such as deciphering local phrases that baffle her (“ni madres” among them), she cannot seem to come to terms with Mexico. That is, she cannot understand what it means to belong there. Throughout, she quotes from Octavio Paz’s The Labyrinth of Solitude, but this interpretive lens only affords her a theoretical, unfeeling understanding of the country. While sitting in a café, she tries to make sense of the lack of uniformity surrounding her:

While Uhart is dogged in her pursuit of strangeness and understanding, she doesn’t always succeed when it comes to the latter. In “Off to Mexico,” Uhart sets off to Guadalajara and Mexico City for an international book fair. And while she has her idiosyncratic goals, such as deciphering local phrases that baffle her (“ni madres” among them), she cannot seem to come to terms with Mexico. That is, she cannot understand what it means to belong there. Throughout, she quotes from Octavio Paz’s The Labyrinth of Solitude, but this interpretive lens only affords her a theoretical, unfeeling understanding of the country. While sitting in a café, she tries to make sense of the lack of uniformity surrounding her:

The ground is a kaleidoscope—not one mosaic is the same as the other. […] Could it be that this tile design is faithful to some Aztec decor, just as the Virgin of Guadalupe […] seems to be a continuation of Tonantzin, the goddess of fertility? Uniformity does not exist, not in the color of taxis, the floor tiles of the café, or the objects blessed in the cathedral. I can’t quite get a sense of the Mexican way. […] I take a cab to the hotel, which is tucked away in a corner, a refuge of sorts.

For Uhart, Mexico is “colorful and over the top.” She has done her research, but the feeling of Mexicanness eludes her. Unlike other stories in this collection, “Off to Mexico” feels more insular, with Uhart casting her gaze inwards, as well as focusing on sterile environments like the hotel bar—the sort of place that could be anywhere. When faced with bigger cities, Uhart struggles; within them, the intensity and breadth of life leave little room for the individual. As Clarice Lispector once quipped, “I am not going to be autobiographical, I want to be ‘bio.’” Like in “Fabricio,” these big city stories provide a surplus of spectacle; with so much demanding to be looked at, there isn’t anytime for introspection. Uhart finds herself more comfortable in the village of Irazusta, where “it’d be possible to cover the town about thirty times a day, back and forth… [and] once you get up, you are already outside.”

One of the more endearing aspects of A Question of Belonging is Uhart’s readiness to admit her failings. Despite not getting her head around the Mexican way, she is content to “finally give up on trying to understand” and to simply look—dar una mirada. Equally, the privilege of traveling is not lost on her; in “Around the Corner,” Uhart gives up mainland Cartagena for a shantytown just across the water. Her motive for the trip is typical of her: “Everyone’s going so far away… I should go somewhere too, but just around the corner.” Having escaped the insistent street vendors in the heart of the port city, she is disappointed to find more on the other side, though she takes solace in a polite young man who agrees to show her the town’s ruins. He is smart, but had to drop out of school; there are simply more important things to be done around there, like sourcing clean water.

Upset by the reality of the world she has stumbled on, Uhart starts to play the revolutionary, trying to solve all their problems at once: the vendors can travel just like her—it’s really no great luxury—or even just sell their goods in Cartagena and make a little extra. But she soon realizes that her ideas have occurred to those stuck there a thousand times over: “nobody wants to let us on their ships [to travel], once they know we’re Colombians [and] you need a permit [to sell in Cartagena]… real pricey.” The story closes with Uhart waiting for a boat to get her out of there. While she waits, she’s confronted by a child begging. All she has on her are the necklaces she bought from the vendors and large bills; she hands the kid a necklace.

“He should have cursed me out,” she writes. “I would’ve done that if I were him.” Realizing she cannot help people who really need it, a sudden self-awareness arises by the story’s end; she won’t always be met with open arms in her travels. Like her failure to come to terms with Mexico, Uhart again plays up her failures rather than hiding them—or hiding from them. Understanding and change are not always within her grasp, and knowing when this is true is one of Uhart’s greatest strengths.