Mentioned in:

Most Anticipated: The Great Winter 2025 Preview

It's cold, it's grey, its bleak—but winter, at the very least, brings with it a glut of anticipation-inducing books. Here you’ll find nearly 100 titles that we’re excited to cozy up with this season. Some we’ve already read in galley form; others we’re simply eager to devour based on their authors, subjects, or blurbs. We'd love for you to find your next great read among them.

The Millions will be taking a hiatus for the next few months, but we hope to see you soon.

—Sophia Stewart, editor

January

The Legend of Kumai by Shirato Sanpei, tr. Richard Rubinger (Drawn & Quarterly)

The epic 10-volume series, a touchstone of longform storytelling in manga now published in English for the first time, follows outsider Kamui in 17th-century Japan as he fights his way up from peasantry to the prized role of ninja. —Michael J. Seidlinger

The Life of Herod the Great by Zora Neale Hurston (Amistad)

In the years before her death in 1960, Hurston was at work on what she envisioned as a continuation of her 1939 novel, Moses, Man of the Mountain. Incomplete, nearly lost to fire, and now published for the first time alongside scholarship from editor Deborah G. Plant, Hurston’s final manuscript reimagines Herod, villain of the New Testament Gospel accounts, as a magnanimous and beloved leader of First Century Judea. —Jonathan Frey

Mood Machine by Liz Pelly (Atria)

When you eagerly posted your Spotify Wrapped last year, did you notice how much of what you listened to tended to sound... the same? Have you seen all those links to Bandcamp pages your musician friends keep desperately posting in the hopes that maybe, just maybe, you might give them money for their art? If so, this book is for you. —John H. Maher

My Country, Africa by Andrée Blouin (Verso)

African revolutionary Blouin recounts a radical life steeped in activism in this vital autobiography, from her beginnings in a colonial orphanage to her essential role in the continent's midcentury struggles for decolonization. —Sophia M. Stewart

The First and Last King of Haiti by Marlene L. Daut (Knopf)

Donald Trump repeatedly directs extraordinary animus towards Haiti and Haitians. This biography of Henry Christophe—the man who played a pivotal role in the Haitian Revolution—might help Americans understand why. —Claire Kirch

The Bewitched Bourgeois by Dino Buzzati, tr. Lawrence Venuti (NYRB)

This is the second story collection, and fifth book, by the absurdist-leaning midcentury Italian writer—whose primary preoccupation was war novels that blend the brutal with the fantastical—to get the NYRB treatment. May it not be the last. —JHM

Y2K by Colette Shade (Dey Street)

The recent Y2K revival mostly makes me feel old, but Shade's essay collection deftly illuminates how we got here, connecting the era's social and political upheavals to today. —SMS

Darkmotherland by Samrat Upadhyay (Penguin)

In a vast dystopian reimagining of Nepal, Upadhyay braids narratives of resistance (political, personal) and identity (individual, societal) against a backdrop of natural disaster and state violence. The first book in nearly a decade from the Whiting Award–winning author of Arresting God in Kathmandu, this is Upadhyay’s most ambitious yet. —JF

Metamorphosis by Ross Jeffery (Truborn)

From the author of I Died Too, But They Haven’t Buried Me Yet, a woman leads a double life as she loses her grip on reality by choice, wearing a mask that reflects her inner demons, as she descends into a hell designed to reveal the innermost depths of her grief-stricken psyche. —MJS

The Containment by Michelle Adams (FSG)

Legal scholar Adams charts the failure of desegregation in the American North through the story of the struggle to integrate suburban schools in Detroit, which remained almost completely segregated nearly two decades after Brown v. Board. —SMS

Death of the Author by Nnedi Okorafor (Morrow)

African Futurist Okorafor’s book-within-a-book offers interchangeable cover images, one for the story of a disabled, Black visionary in a near-present day and the other for the lead character’s speculative posthuman novel, Rusted Robots. Okorafor deftly keeps the alternating chapters and timelines in conversation with one another. —Nathalie op de Beeck

Open Socrates by Agnes Callard (Norton)

Practically everything Agnes Callard says or writes ushers in a capital-D Discourse. (Remember that profile?) If she can do the same with a study of the philosophical world’s original gadfly, culture will be better off for it. —JHM

Aflame by Pico Iyer (Riverhead)

Presumably he finds time to eat and sleep in there somewhere, but it certainly appears as if Iyer does nothing but travel and write. His latest, following 2023’s The Half Known Life, makes a case for the sublimity, and necessity, of silent reflection. —JHM

The In-Between Bookstore by Edward Underhill (Avon)

A local bookstore becomes a literal portal to the past for a trans man who returns to his hometown in search of a fresh start in Underhill's tender debut. —SMS

Good Girl by Aria Aber (Hogarth)

Aber, an accomplished poet, turns to prose with a debut novel set in the electric excess of Berlin’s bohemian nightlife scene, where a young German-born Afghan woman finds herself enthralled by an expat American novelist as her country—and, soon, her community—is enflamed by xenophobia. —JHM

The Orange Eats Creeps by Grace Krilanovich (Two Dollar Radio)

Krilanovich’s 2010 cult classic, about a runaway teen with drug-fueled ESP who searches for her missing sister across surreal highways while being chased by a killer named Dactyl, gets a much-deserved reissue. —MJS

Mona Acts Out by Mischa Berlinski (Liveright)

In the latest novel from the National Book Award finalist, a 50-something actress reevaluates her life and career when #MeToo allegations roil the off-off-Broadway Shakespearean company that has cast her in the role of Cleopatra. —SMS

Something Rotten by Andrew Lipstein (FSG)

A burnt-out couple leave New York City for what they hope will be a blissful summer in Denmark when their vacation derails after a close friend is diagnosed with a rare illness and their marriage is tested by toxic influences. —MJS

The Sun Won't Come Out Tomorrow by Kristen Martin (Bold Type)

Martin's debut is a cultural history of orphanhood in America, from the 1800s to today, interweaving personal narrative and archival research to upend the traditional "orphan narrative," from Oliver Twist to Annie. —SMS

We Do Not Part by Han Kang, tr. E. Yaewon and Paige Aniyah Morris (Hogarth)

Kang’s Nobel win last year surprised many, but the consistency of her talent certainly shouldn't now. The latest from the author of The Vegetarian—the haunting tale of a Korean woman who sets off to save her injured friend’s pet at her home in Jeju Island during a deadly snowstorm—will likely once again confront the horrors of history with clear eyes and clarion prose. —JHM

We Are Dreams in the Eternal Machine by Deni Ellis Béchard (Milkweed)

As the conversation around emerging technology skews increasingly to apocalyptic and utopian extremes, Béchard’s latest novel adopts the heterodox-to-everyone approach of embracing complexity. Here, a cadre of characters is isolated by a rogue but benevolent AI into controlled environments engineered to achieve their individual flourishing. The AI may have taken over, but it only wants to best for us. —JF

The Harder I Fight the More I Love You by Neko Case (Grand Central)

Singer-songwriter Case, a country- and folk-inflected indie rocker and sometime vocalist for the New Pornographers, takes her memoir’s title from her 2013 solo album. Followers of PNW music scene chronicles like Kathleen Hanna’s Rebel Girl and drummer Steve Moriarty’s Mia Zapata and the Gits will consider Case’s backstory a must-read. —NodB

The Loves of My Life by Edmund White (Bloomsbury)

The 85-year-old White recounts six decades of love and sex in this candid and erotic memoir, crafting a landmark work of queer history in the process. Seminal indeed. —SMS

Blob by Maggie Su (Harper)

In Su’s hilarious debut, Vi Liu is a college dropout working a job she hates, nothing really working out in her life, when she stumbles across a sentient blob that she begins to transform as her ideal, perfect man that just might resemble actor Ryan Gosling. —MJS

Sinkhole and Other Inexplicable Voids by Leyna Krow (Penguin)

Krow’s debut novel, Fire Season, traced the combustible destinies of three Northwest tricksters in the aftermath of an 1889 wildfire. In her second collection of short fiction, Krow amplifies surreal elements as she tells stories of ordinary lives. Her characters grapple with deadly viruses, climate change, and disasters of the Anthropocene’s wilderness. —NodB

Black in Blues by Imani Perry (Ecco)

The National Book Award winner—and one of today's most important thinkers—returns with a masterful meditation on the color blue and its role in Black history and culture. —SMS

Too Soon by Betty Shamieh (Avid)

The timely debut novel by Shamieh, a playwright, follows three generations of Palestinian American women as they navigate war, migration, motherhood, and creative ambition. —SMS

How to Talk About Love by Plato, tr. Armand D'Angour (Princeton UP)

With modern romance on its last legs, D'Angour revisits Plato's Symposium, mining the philosopher's masterwork for timeless, indispensable insights into love, sex, and attraction. —SMS

At Dark, I Become Loathsome by Eric LaRocca (Blackstone)

After Ashley Lutin’s wife dies, he takes the grieving process in a peculiar way, posting online, “If you're reading this, you've likely thought that the world would be a better place without you,” and proceeds to offer a strange ritual for those that respond to the line, equally grieving and lost, in need of transcendence. —MJS

February

No One Knows by Osamu Dazai, tr. Ralph McCarthy (New Directions)

A selection of stories translated in English for the first time, from across Dazai’s career, demonstrates his penchant for exploring conformity and society’s often impossible expectations of its members. —MJS

Mutual Interest by Olivia Wolfgang-Smith (Bloomsbury)

This queer love story set in post–Gilded Age New York, from the author of Glassworks (and one of my favorite Millions essays to date), explores on sex, power, and capitalism through the lives of three queer misfits. —SMS

Pure, Innocent Fun by Ira Madison III (Random House)

This podcaster and pop culture critic spoke to indie booksellers at a fall trade show I attended, regaling us with key cultural moments in the 1990s that shaped his youth in Milwaukee and being Black and gay. If the book is as clever and witty as Madison is, it's going to be a winner. —CK

Gliff by Ali Smith (Pantheon)

The Scottish author has been on the scene since 1997 but is best known today for a seasonal quartet from the late twenty-teens that began in 2016 with Autumn and ended in 2020 with Summer. Here, she takes the genre turn, setting two children and a horse loose in an authoritarian near future. —JHM

Land of Mirrors by Maria Medem, tr. Aleshia Jensen and Daniela Ortiz (D&Q)

This hypnotic graphic novel from one of Spain's most celebrated illustrators follows Antonia, the sole inhabitant of a deserted town, on a color-drenched quest to preserve the dying flower that gives her purpose. —SMS

Bibliophobia by Sarah Chihaya (Random House)

As odes to the "lifesaving power of books" proliferate amid growing literary censorship, Chihaya—a brilliant critic and writer—complicates this platitude in her revelatory memoir about living through books and the power of reading to, in the words of blurber Namwali Serpell, "wreck and redeem our lives." —SMS

Reading the Waves by Lidia Yuknavitch (Riverhead)

Yuknavitch continues the personal story she began in her 2011 memoir, The Chronology of Water. More than a decade after that book, and nearly undone by a history of trauma and the death of her daughter, Yuknavitch revisits the solace she finds in swimming (she was once an Olympic hopeful) and in her literary community. —NodB

The Dissenters by Youssef Rakha (Graywolf)

A son reevaluates the life of his Egyptian mother after her death in Rakha's novel. Recounting her sprawling life story—from her youth in 1960s Cairo to her experience of the 2011 Tahrir Square protests—a vivid portrait of faith, feminism, and contemporary Egypt emerges. —SMS

Tetra Nova by Sophia Terazawa (Deep Vellum)

Deep Vellum has a particularly keen eye for fiction in translation that borders on the unclassifiable. This debut from a poet the press has published twice, billed as the story of “an obscure Roman goddess who re-imagines herself as an assassin coming to terms with an emerging performance artist identity in the late-20th century,” seems right up that alley. —JHM

David Lynch's American Dreamscape by Mike Miley (Bloomsbury)

Miley puts David Lynch's films in conversation with literature and music, forging thrilling and unexpected connections—between Eraserhead and "The Yellow Wallpaper," Inland Empire and "mixtape aesthetics," Lynch and the work of Cormac McCarthy. Lynch devotees should run, not walk. —SMS

There's No Turning Back by Alba de Céspedes, tr. Ann Goldstein (Washington Square)

Goldstein is an indomitable translator. Without her, how would you read Ferrante? Here, she takes her pen to a work by the great Cuban-Italian writer de Céspedes, banned in the fascist Italy of the 1930s, that follows a group of female literature students living together in a Roman boarding house. —JHM

Beta Vulgaris by Margie Sarsfield (Norton)

Named for the humble beet plant and meaning, in a rough translation from the Latin, "vulgar second," Sarsfield’s surreal debut finds a seasonal harvest worker watching her boyfriend and other colleagues vanish amid “the menacing but enticing siren song of the beets.” —JHM

People From Oetimu by Felix Nesi, tr. Lara Norgaard (Archipelago)

The center of Nesi’s wide-ranging debut novel is a police station on the border between East and West Timor, where a group of men have gathered to watch the final of the 1998 World Cup while a political insurgency stirs without. Nesi, in English translation here for the first time, circles this moment broadly, reaching back to the various colonialist projects that have shaped Timor and the lives of his characters. —JF

Brother Brontë by Fernando A. Flores (MCD)

This surreal tale, set in a 2038 dystopian Texas is a celebration of resistance to authoritarianism, a mash-up of Olivia Butler, Ray Bradbury, and John Steinbeck. —CK

Alligator Tears by Edgar Gomez (Crown)

The High-Risk Homosexual author returns with a comic memoir-in-essays about fighting for survival in the Sunshine State, exploring his struggle with poverty through the lens of his queer, Latinx identity. —SMS

Theory & Practice by Michelle De Kretser (Catapult)

This lightly autofictional novel—De Krester's best yet, and one of my favorite books of this year—centers on a grad student's intellectual awakening, messy romantic entanglements, and fraught relationship with her mother as she minds the gap between studying feminist theory and living a feminist life. —SMS

The Lamb by Lucy Rose (Harper)

Rose’s cautionary and caustic folk tale is about a mother and daughter who live alone in the forest, quiet and tranquil except for the visitors the mother brings home, whom she calls “strays,” wining and dining them until they feast upon the bodies. —MJS

Disposable by Sarah Jones (Avid)

Jones, a senior writer for New York magazine, gives a voice to America's most vulnerable citizens, who were deeply and disproportionately harmed by the pandemic—a catastrophe that exposed the nation's disregard, if not outright contempt, for its underclass. —SMS

No Fault by Haley Mlotek (Viking)

Written in the aftermath of the author's divorce from the man she had been with for 12 years, this "Memoir of Romance and Divorce," per its subtitle, is a wise and distinctly modern accounting of the end of a marriage, and what it means on a personal, social, and literary level. —SMS

Enemy Feminisms by Sophie Lewis (Haymarket)

Lewis, one of the most interesting and provocative scholars working today, looks at certain malignant strains of feminism that have done more harm than good in her latest book. In the process, she probes the complexities of gender equality and offers an alternative vision of a feminist future. —SMS

Lion by Sonya Walger (NYRB)

Walger—an successful actor perhaps best known for her turn as Penny Widmore on Lost—debuts with a remarkably deft autobiographical novel (published by NYRB no less!) about her relationship with her complicated, charismatic Argentinian father. —SMS

The Voices of Adriana by Elvira Navarro, tr. Christina MacSweeney (Two Lines)

A Spanish writer and philosophy scholar grieves her mother and cares for her sick father in Navarro's innovative, metafictional novel. —SMS

Autotheories ed. Alex Brostoff and Vilashini Cooppan (MIT)

Theory wonks will love this rigorous and surprisingly playful survey of the genre of autotheory—which straddles autobiography and critical theory—with contributions from Judith Butler, Jamieson Webster, and more.

Fagin the Thief by Allison Epstein (Doubleday)

I enjoy retellings of classic novels by writers who turn the spotlight on interesting minor characters. This is an excursion into the world of Charles Dickens, told from the perspective iconic thief from Oliver Twist. —CK

Crush by Ada Calhoun (Viking)

Calhoun—the masterful memoirist behind the excellent Also A Poet—makes her first foray into fiction with a debut novel about marriage, sex, heartbreak, all-consuming desire. —SMS

Show Don't Tell by Curtis Sittenfeld (Random House)

Sittenfeld's observations in her writing are always clever, and this second collection of short fiction includes a tale about the main character in Prep, who visits her boarding school decades later for an alumni reunion. —CK

Right-Wing Woman by Andrea Dworkin (Picador)

One in a trio of Dworkin titles being reissued by Picador, this 1983 meditation on women and American conservatism strikes a troublingly resonant chord in the shadow of the recent election, which saw 45% of women vote for Trump. —SMS

The Talent by Daniel D'Addario (Scout)

If your favorite season is awards, the debut novel from D'Addario, chief correspondent at Variety, weaves an awards-season yarn centering on five stars competing for the Best Actress statue at the Oscars. If you know who Paloma Diamond is, you'll love this. —SMS

Death Takes Me by Cristina Rivera Garza, tr. Sarah Booker and Robin Myers (Hogarth)

The Pulitzer winner’s latest is about an eponymously named professor who discovers the body of a mutilated man with a bizarre poem left with the body, becoming entwined in the subsequent investigation as more bodies are found. —MJS

The Strange Case of Jane O. by Karen Thompson Walker (Random House)

Jane goes missing after a sudden a debilitating and dreadful wave of symptoms that include hallucinations, amnesia, and premonitions, calling into question the foundations of her life and reality, motherhood and buried trauma. —MJS

Song So Wild and Blue by Paul Lisicky (HarperOne)

If it weren’t Joni Mitchell’s world with all of us just living in it, one might be tempted to say the octagenarian master songstress is having a moment: this memoir of falling for the blue beauty of Mitchell’s work follows two other inventive books about her life and legacy: Ann Powers's Traveling and Henry Alford's I Dream of Joni. —JHM

Mornings Without Mii by Mayumi Inaba, tr. Ginny Tapley (FSG)

A woman writer meditates on solitude, art, and independence alongside her beloved cat in Inaba's modern classic—a book so squarely up my alley I'm somehow embarrassed. —SMS

True Failure by Alex Higley (Coffee House)

When Ben loses his job, he decides to pretend to go to work while instead auditioning for Big Shot, a popular reality TV show that he believes might be a launchpad for his future successes. —MJS

March

Woodworking by Emily St. James (Crooked Reads)

Those of us who have been reading St. James since the A.V. Club days may be surprised to see this marvelous critic's first novel—in this case, about a trans high school teacher befriending one of her students, the only fellow trans woman she’s ever met—but all the more excited for it. —JHM

Optional Practical Training by Shubha Sunder (Graywolf)

Told as a series of conversations, Sunder’s debut novel follows its recently graduated Indian protagonist in 2006 Cambridge, Mass., as she sees out her student visa teaching in a private high school and contriving to find her way between worlds that cannot seem to comprehend her. Quietly subversive, this is an immigration narrative to undermine the various reductionist immigration narratives of our moment. —JF

Love, Queenie by Mayukh Sen (Norton)

Merle Oberon, one of Hollywood's first South Asian movie stars, gets her due in this engrossing biography, which masterfully explores Oberon's painful upbringing, complicated racial identity, and much more. —SMS

The Age of Choice by Sophia Rosenfeld (Princeton UP)

At a time when we are awash with options—indeed, drowning in them—Rosenfeld's analysis of how our modingn idea of "freedom" became bound up in the idea of personal choice feels especially timely, touching on everything from politics to romance. —SMS

Sucker Punch by Scaachi Koul (St. Martin's)

One of the internet's funniest writers follows up One Day We'll All Be Dead and None of This Will Matter with a sharp and candid collection of essays that sees her life go into a tailspin during the pandemic, forcing her to reevaluate her beliefs about love, marriage, and what's really worth fighting for. —SMS

The Mysterious Disappearance of the Marquise of Loria by José Donoso, tr. Megan McDowell (New Directions)

The ever-excellent McDowell translates yet another work by the influential Chilean author for New Directions, proving once again that Donoso had a knack for titles: this one follows up 2024’s behemoth The Obscene Bird of Night. —JHM

Remember This by Anthony Giardina (FSG)

On its face, it’s another book about a writer living in Brooklyn. A layer deeper, it’s a book about fathers and daughters, occupations and vocations, ethos and pathos, failure and success. —JHM

Ultramarine by Mariette Navarro (Deep Vellum)

In this metaphysical and lyrical tale, a captain known for sticking to protocol begins losing control not only of her crew and ship but also her own mind. —MJS

We Tell Ourselves Stories by Alissa Wilkinson (Liveright)

Amid a spate of new books about Joan Didion published since her death in 2021, this entry by Wilkinson (one of my favorite critics working today) stands out for its approach, which centers Hollywood—and its meaning-making apparatus—as an essential key to understanding Didion's life and work. —SMS

Seven Social Movements that Changed America by Linda Gordon (Norton)

This book—by a truly renowned historian—about the power that ordinary citizens can wield when they organize to make their community a better place for all could not come at a better time. —CK

Mothers and Other Fictional Characters by Nicole Graev Lipson (Chronicle Prism)

Lipson reconsiders the narratives of womanhood that constrain our lives and imaginations, mining the canon for alternative visions of desire, motherhood, and more—from Kate Chopin and Gwendolyn Brooks to Philip Roth and Shakespeare—to forge a new story for her life. —SMS

Goddess Complex by Sanjena Sathian (Penguin)

Doppelgängers have been done to death, but Sathian's examination of Millennial womanhood—part biting satire, part twisty thriller—breathes new life into the trope while probing the modern realities of procreation, pregnancy, and parenting. —SMS

Stag Dance by Torrey Peters (Random House)

The author of Detransition, Baby offers four tales for the price of one: a novel and three stories that promise to put gender in the crosshairs with as sharp a style and swagger as Peters’ beloved latest. The novel even has crossdressing lumberjacks. —JHM

On Breathing by Jamieson Webster (Catapult)

Webster, a practicing psychoanalyst and a brilliant writer to boot, explores that most basic human function—breathing—to address questions of care and interdependence in an age of catastrophe. —SMS

Unusual Fragments: Japanese Stories (Two Lines)

The stories of Unusual Fragments, including work by Yoshida Tomoko, Nobuko Takai, and other seldom translated writers from the same ranks as Abe and Dazai, comb through themes like alienation and loneliness, from a storm chaser entering the eye of a storm to a medical student observing a body as it is contorted into increasingly violent positions. —MJS

The Antidote by Karen Russell (Knopf)

Russell has quipped that this Dust Bowl story of uncanny happenings in Nebraska is the “drylandia” to her 2011 Florida novel, Swamplandia! In this suspenseful account, a woman working as a so-called prairie witch serves as a storage vault for her townspeople’s most troubled memories of migration and Indigenous genocide. With a murderer on the loose, a corrupt sheriff handling the investigation, and a Black New Deal photographer passing through to document Americana, the witch loses her memory and supernatural events parallel the area’s lethal dust storms. —NodB

On the Clock by Claire Baglin, tr. Jordan Stump (New Directions)

Baglin's bildungsroman, translated from the French, probes the indignities of poverty and service work from the vantage point of its 20-year-old narrator, who works at a fast-food joint and recalls memories of her working-class upbringing. —SMS

Motherdom by Alex Bollen (Verso)

Parenting is difficult enough without dealing with myths of what it means to be a good mother. I who often felt like a failure as a mother appreciate Bollen's focus on a more realistic approach to parenting. —CK

The Magic Books by Anne Lawrence-Mathers (Yale UP)

For that friend who wants to concoct the alchemical elixir of life, or the person who cannot quit Susanna Clark’s Jonathan Strange and Mr. Norrell, Lawrence-Mathers collects 20 illuminated medieval manuscripts devoted to magical enterprise. Her compendium includes European volumes on astronomy, magical training, and the imagined intersection between science and the supernatural. —NodB

Theft by Abdulrazak Gurnah (Riverhead)

The first novel by the Tanzanian-British Nobel laureate since his surprise win in 2021 is a story of class, seismic cultural change, and three young people in a small Tanzania town, caught up in both as their lives dramatically intertwine. —JHM

Twelve Stories by American Women, ed. Arielle Zibrak (Penguin Classics)

Zibrak, author of a delicious volume on guilty pleasures (and a great essay here at The Millions), curates a dozen short stories by women writers who have long been left out of American literary canon—most of them women of color—from Frances Ellen Watkins Harper to Zitkala-Ša. —SMS

I'll Love You Forever by Giaae Kwon (Holt)

K-pop’s sky-high place in the fandom landscape made a serious critical assessment inevitable. This one blends cultural criticism with memoir, using major artists and their careers as a lens through which to view the contemporary Korean sociocultural landscape writ large. —JHM

The Buffalo Hunter Hunter by Stephen Graham Jones (Saga)

Jones, the acclaimed author of The Only Good Indians and the Indian Lake Trilogy, offers a unique tale of historical horror, a revenge tale about a vampire descending upon the Blackfeet reservation and the manifold of carnage in their midst. —MJS

True Mistakes by Lena Moses-Schmitt (University of Arkansas Press)

Full disclosure: Lena is my friend. But part of why I wanted to be her friend in the first place is because she is a brilliant poet. Selected by Patricia Smith as a finalist for the Miller Williams Poetry Prize, and blurbed by the great Heather Christle and Elisa Gabbert, this debut collection seeks to turn "mistakes" into sites of possibility. —SMS

Perfection by Vicenzo Latronico, tr. Sophie Hughes (NYRB)

Anna and Tom are expats living in Berlin enjoying their freedom as digital nomads, cultivating their passion for capturing perfect images, but after both friends and time itself moves on, their own pocket of creative freedom turns boredom, their life trajectories cast in doubt. —MJS

Guatemalan Rhapsody by Jared Lemus (Ecco)

Jemus's debut story collection paint a composite portrait of the people who call Guatemala home—and those who have left it behind—with a cast of characters that includes a medicine man, a custodian at an underfunded college, wannabe tattoo artists, four orphaned brothers, and many more.

Pacific Circuit by Alexis Madrigal (MCD)

The Oakland, Calif.–based contributing writer for the Atlantic digs deep into the recent history of a city long under-appreciated and under-served that has undergone head-turning changes throughout the rise of Silicon Valley. —JHM

Barbara by Joni Murphy (Astra)

Described as "Oppenheimer by way of Lucia Berlin," Murphy's character study follows the titular starlet as she navigates the twinned convulsions of Hollywood and history in the Atomic Age.

Sister Sinner by Claire Hoffman (FSG)

This biography of the fascinating Aimee Semple McPherson, America's most famous evangelist, takes religion, fame, and power as its subjects alongside McPherson, whose life was suffused with mystery and scandal. —SMS

Trauma Plot by Jamie Hood (Pantheon)

In this bold and layered memoir, Hood confronts three decades of sexual violence and searches for truth among the wreckage. Kate Zambreno calls Trauma Plot the work of "an American Annie Ernaux." —SMS

Hey You Assholes by Kyle Seibel (Clash)

Seibel’s debut story collection ranges widely from the down-and-out to the downright bizarre as he examines with heart and empathy the strife and struggle of his characters. —MJS

James Baldwin by Magdalena J. Zaborowska (Yale UP)

Zaborowska examines Baldwin's unpublished papers and his material legacy (e.g. his home in France) to probe about the great writer's life and work, as well as the emergence of the "Black queer humanism" that Baldwin espoused. —CK

Stop Me If You've Heard This One by Kristen Arnett (Riverhead)

Arnett is always brilliant and this novel about the relationship between Cherry, a professional clown, and her magician mentor, "Margot the Magnificent," provides a fascinating glimpse of the unconventional lives of performance artists. —CK

Paradise Logic by Sophie Kemp (S&S)

The deal announcement describes the ever-punchy writer’s debut novel with an infinitely appealing appellation: “debauched picaresque.” If that’s not enough to draw you in, the truly unhinged cover should be. —JHM

[millions_email]

A Year in Reading: 2024

Welcome to the 20th (!) installment of The Millions' annual Year in Reading series, which gathers together some of today's most exciting writers and thinkers to share the books that shaped their year. YIR is not a collection of yearend best-of lists; think of it, perhaps, as an assemblage of annotated bibliographies. We've invited contributors to reflect on the books they read this year—an intentionally vague prompt—and encouraged them to approach the assignment however they choose.

In writing about our reading lives, as YIR contributors are asked to do, we inevitably write about our personal lives, our inner lives. This year, a number of contributors read their way through profound grief and serious illness, through new parenthood and cross-country moves. Some found escape in frothy romances, mooring in works of theology, comfort in ancient epic poetry. More than one turned to the wisdom of Ursula K. Le Guin. Many describe a book finding them just when they needed it.

Interpretations of the assignment were wonderfully varied. One contributor, a music critic, considered the musical analogs to the books she read, while another mapped her reads from this year onto constellations. Most people's reading was guided purely by pleasure, or else a desire to better understand events unfolding in their lives or larger the world. Yet others centered their reading around a certain sense of duty: this year one contributor committed to finishing the six Philip Roth novels he had yet to read, an undertaking that he likens to “eating a six-pack of paper towels.” (Lucky for us, he included in his essay his final ranking of Roth's oeuvre.)

The books that populate these essays range widely, though the most commonly noted title this year was Tony Tulathimutte’s story collection Rejection. The work of newly minted National Book Award winner Percival Everett, particularly his acclaimed novel James, was also widely read and written about. And as the genocide of Palestinians in Gaza enters its second year, many contributors sought out Isabella Hammad’s searing, clear-eyed essay Recognizing the Stranger.

Like so many endeavors in our chronically under-resourced literary community, Year in Reading is a labor of love. The Millions is a one-person editorial operation (with an invaluable assist from SEO maven Dani Fishman), and producing YIR—and witnessing the joy it brings contributors and readers alike—has been the highlight of my tenure as editor. I’m profoundly grateful for the generosity of this year’s contributors, whose names and entries will be revealed below over the next three weeks, concluding on Wednesday, December 18. Be sure to subscribe to The Millions’ free newsletter to get the week’s entries sent straight to your inbox each Friday.

—Sophia Stewart, editor

Becca Rothfeld, author of All Things Are Too Small

Carvell Wallace, author of Another Word for Love

Charlotte Shane, author of An Honest Woman

Brianna Di Monda, writer and editor

Nell Irvin Painter, author of I Just Keep Talking

Carrie Courogen, author of Miss May Does Not Exist

Ayşegül Savaş, author of The Anthropologists

Zachary Issenberg, writer

Tony Tulathimutte, author of Rejection

Ann Powers, author of Traveling: On the Path of Joni Mitchell

Lidia Yuknavitch, author of Reading the Waves

Nicholas Russell, writer and critic

Daniel Saldaña París, author of Planes Flying Over a Monster

Lili Anolik, author of Didion and Babitz

Deborah Ghim, editor

Emily Witt, author of Health and Safety

Nathan Thrall, author of A Day in the Life of Abed Salama

Lena Moses-Schmitt, author of True Mistakes

Jeremy Gordon, author of See Friendship

John Lee Clark, author of Touch the Future

Ellen Wayland-Smith, author of The Science of Last Things

Edwin Frank, publisher and author of Stranger Than Fiction

Sophia Stewart, editor of The Millions

A Year in Reading Archives: 2023, 2022, 2021, 2020, 2019, 2018, 2017, 2016, 2015, 2014, 2013, 2011, 2010, 2009, 2008, 2007, 2006, 2005

Hard to Get: Books That Resist You

1. Recently, for the fourth or fifth time in my life, I started trying to read James Salter's A Sport and a Pastime. I bought my copy many years ago, after falling in love with his story collections and enjoying Light Years, probably his best-known novel. A Sport and a Pastime, though not obscure, has a whiff of the occult about it, with its hazy voyeuristic sex and a title taken from the Koran. It is commonly and unironically referred to as an “erotic masterpiece.” Writing for The New York Times Review of Books, Reynolds Price said, "Of living novelists, none has produced a novel I admire more than A Sport and a Pastime...it's as nearly perfect as any American fiction I know.”

Despite these points of interest and an agreeable running length of right around 200 pages, over two decades, I’ve found myself consistently stymied by something in this novel. I can still clearly remember the thrill of finding it at a used bookstore (it was, I believe, out of print at the time, or at any rate not widely available), taking it home, cracking it open along with a beer, and…not reading it.

This has been my experience with A Sport and a Pastime, our relationship, so to speak, over the last two decades. Maybe it's the strange narrative setup, the unnamed narrator employed mostly as a camera for the erotic exploits of the central couple. Maybe it’s the slowness of the plot. More likely, I think, it's something wrong with me.

There is a type of book, I find, that falls in this

category: books that resist you. This is different from books you think are

bad, or books you don’t want to read. These are books you want to read, but for

some reason are unable to. These are books that, if anything, you somehow fail,

not being up to the task.

2. The obverse of this is the kind of book you helplessly return to again and again. Some personal examples: The Patrick Melrose cycle, Disgrace, A House for Mr. Biswas, The Talented Mr. Ripley, Flannery O’Connor’s The Collected Stories, The Big Sleep, Pride and Prejudice, Madame Bovary. These are books that my taste and intellect, such as they are, somehow notch into like teeth into a greater gear. Sometimes you outgrow these books, as I feel I have with, say, Kurt Vonnegut’s corpus, but by and large these are books that I have read throughout my adulthood and continue getting different things out of with each read.

I’m not sure this is a good thing. In a way, this kind of reading preserves a personal stasis, forever reconfirming your excellent taste in literature, always agreeing with you. They are the yes-men of your library—in reading, as in life, it is good to find people who will tell you no: No, maybe you are not smart enough for this; no, you are not entitled to an immediate endorphin release upon opening me up; no, you cannot read me.

3. Another book of the former type: Malcolm Lowry’s Under the Volcano. This is an especially irksome one, a novel I’ve been attracted to for years, then repulsed by every time I open the cover. My experience with this kind of book does feel, in its way, analogous to a certain kind of romantic flirtation, a pas de deux of advance and retreat—never quite enough advance to win the book’s affection; never quite enough retreat to finally put me off. I have long been drawn to The Volcano and Lowry's shared mythos: suicidal alcoholism in a hot country. I’m intrigued by its aura and stature as one of the greatest books of the century. I want to read it.

But man, that first chapter—I’ve read it several times and never made it any further. From memory: the initial, oblique conversation between Laruelle and Dr. Vigil (okay, I looked these up) on the hotel balcony as they sip anis and gaze out at the titular volcano; the references to the Consul, Fermin (who I am aware, theoretically, will at some point become the actual main character), and shared recollections of his misbehavior and disappearance; Laruelle’s interminable saunter down the hill and into town; an equally protracted sojourn at a bar that, again, if memory serves, is strangely connected to a movie theater. There, Laruelle is given a book for some reason. Other things happen, or don’t. My memory of that chapter feels consistent with the mode in which I have most frequently encountered it: falling asleep in bed. Which is to say that the first part is most vivid, and, as it goes on, the lights grow dimmer and the enterprise seems to begin repeating itself.

[millions_ad]

4. But this is clearly user error. Maybe it’s a coincidence, but I notice, with both Under the Volcano and A Sport and a Pastime, a personal difficulty with books that dwell too long in the perspective of a peripheral character. No matter how good the language and description—and the language and description in Under the Volcano are, of course, very good—at a certain point I want it to get a move on. The truth probably is that I am not an especially good, or patient, reader. Maybe good compared to the average casual reader, but not compared to many other writers and academics I know, who seem to omnivorously inhale all manner of book no matter how difficult or slow, like woodchippers dispatching balsa.

The truth probably is that my normal reading taste level lands somewhere just north of middlebrow. I have read Ulysses (and is there a more loathsome sentence to type than this?—the literary equivalent of mentioning your SAT score). But I skipped large swaths of the especially difficult chapters like “Proteus” and “Oxen of the Sun.” My highbrow taste is defined by a narrow niche of books that are well-written and also, for lack of a better word, fun.

Nabokov’s novels, for example—as strenuously modern and well-written as they are, they also move. They are not boring. The reader’s attention is rewarded like a good dog, receiving periodic treats for trotting along behind the master. “Fun” is a strange descriptor to apply to a book about pedophilia, but in spite of its subject matter, Lolita is, well, a pretty rollicking read (really, this is the novel's perverse central project, to coax a reader into an aesthetic pleasure that mirrors, horribly, Humbert's), jammed with the darkest comedy, suspense, wordplay, twists, turns, and the climactic ending to end all climactic endings. It is fun, as is Pnin, as is Pale Fire. Even early juvenilia like The Eye keeps you interested.

5. Interestingness, is, of course, in the eye of the beholder. But would it be completely unfair to say that a large swath of what we consider literary fiction is, by its nature and/or by design, uneventful? My Struggle is an obvious recent example—the first 200 pages of Book One are the story of the time young Karl Ove and a friend tried (spoiler alert: successfully) to get a case of beer to a high school party. Later, he devotes dozens of pages to the description of cleaning a bathroom.

Knausgaard’s work may provide an extreme example, but it remains generally true that in what we consider highbrow literary fiction, plotlessness often serves as a genre and status marker. Presumably this has something to do with a semi-consciously received idea of literary fiction being realistic fiction, and reality being uneventful. Brian Cox, portraying the screenwriting coach Robert McKee in Adaptation, had this to say on the matter:

Nothing happens in the world? Are you out of your fucking mind? People are murdered every day. There's genocide, war, corruption. Every fucking day, somewhere in the world, somebody sacrifices his life to save someone else. Every fucking day, someone, somewhere takes a conscious decision to destroy someone else. People find love, people lose it. For Christ's sake, a child watches her mother beaten to death on the steps of a church. Someone goes hungry. Somebody else betrays his best friend for a woman. If you can't find that stuff in life, then you, my friend, don't know crap about life!

My Struggle received overwhelming critical praise for its rejection of that stuff and for its strenuous, almost ostentatious, dramatization of the banal and prosaic—all of the bits that typically get cut out of plot-driven fiction. Zadie Smith, praising the books, said, “Like Warhol, he makes no attempt to be interesting.” The intellectual enshrinement of non-event is worth considering on its merits for a moment. It might be argued that this high literary conception of real life as a frictionless enactment of societal rituals, unconscious consumerism, and media absorption is essentially a safe, bourgeois version of reality, and that plot-free literary fiction aestheticizes that principle of non-event. And so it might further be argued that literature that tests a reader’s ability to endure boredom and plotlessness is, on some level, testing the degree of that reader’s integration into the late capitalist fantasy of a perfectly isolated and insulated existence just as much as a writer like James Patterson affirms that integration by the obverse means of testing a reader’s willingness to accept product as art. The extremes of event and non-event both affirm this version.

6.Then again, maybe (probably) this is bullshit, rigging up an objective rationale for personal taste. And besides, I can think of so many counterexamples—books in which nothing much happens that I adore. The Outline trilogy, for example, or Ben Lerner’s Leaving the Atocha Station. I would listen to Faye listening to people until the end of time; I’d follow Lerner’s valium-popping liar Adam Gordon to the ends of the world. In the end, it probably just comes down to something ineffable and mysterious in the writing. That connection between author and reader, the partnership and compact that must occur, something in the handshake that slips, that doesn’t quite hold.

[millions_email]

I Had No Choice but to Write It: Elisa Albert Interviews Ian MacKenzie

Feast Days, the second novel from Ian MacKenzie, is narrated by Emma, a “trailing spouse” who accompanies her husband to the Brazillian megacity of São Paulo. Keenly observant and devastatingly intelligent, Emma feels “an affliction of vagueness” about her own purpose in the here and now. Her ambivalence is framed by the country’s political unrest, and the sharp divide between the haves and have-nots—as witnessed in the mass protest over corruption and inequality from behind the floor-to-ceiling windows in her luxury high-rise apartment.

Emma’s desire to somehow do something is the central movement of this lyrical, spare, deeply prescient entry in the Americans-abroad canon. Her loss of political and personal innocence is at once familiar and new, darkly comic, and, thanks to MacKenzie’s unerring ear, tonally flawless. It's a superb novel about unrest within and without.

Ian MacKenzie spoke with me about the risks (and necessities) inherent in his decision to write in a woman’s voice, what it means to inhabit vantage point not your own, how Feast Days grew out of MacKenzie’s own time spent living in Brazil as a foreign service officer, and how the 2013 protests in Brazil over the country’s extreme economic and political inequality compared to the Occupy movement here in the States.

The Millions: This is your second novel. How did the process on the whole compare to that with your first?

Ian MacKenzie: I published my first novel, City of Strangers, in 2009. At the time, I was doing freelance editing work to make ends meet, living in Brooklyn, subletting rooms from friends, 27 years old. I'd been working on that book for maybe three years, after failing to publish an earlier novel and leaving a job as a high school teacher in order to have more time to write. I had this whole idea of what Being a Writer meant, an idea founded on received notions about personal and artistic freedom, and which involved living in New York City, keeping strange hours, and remaining sufficiently unattached to uproot myself on a whim. I don't think I was really an adult yet. In other words, I was a cliché.

Now it's 2018. My second novel, Feast Days, seems to me to be the work almost of a different writer entirely, and it's inarguably the work of a different person. I'm married, I have a real job that has nothing to do with writing, I haven't lived in New York for almost a decade, and I have a daughter, too, who was born only a few weeks after the book was sold to its publisher. Almost every prejudice I used to hold about what it means to be a writer has been demolished, happily so.

When I was working on my first novel, I had nothing to do but write and think about writing and think about Being a Writer. I couldn't imagine anything more important in the world. By the time I was working on my second novel, however, I was writing in what scraps of time I could pick up in and around a demanding job, a marriage—in and around real life, in other words. I think, looking back, that I wrote City of Strangers as much because I wanted to be a writer as because I wanted to write that particular book, let alone needed to write it. I was in a rush to get somewhere. Feast Days I wrote because I had no choice but to write it.

As a husband and a father, I have a completely different sense now of what matters. Writing is no longer the most important thing in the world. That's another cliché, surely. And, by the way, I also have a sense for what it's like not to have the time or energy, around the demands of adult life, to read a novel or even two in a week, to give priority to fiction in that way. Perhaps that's blasphemous for a writer to say, but from this knowledge I have an appreciation for what you're asking of people when you send a book out into the world. It's not just a matter of competing for attention in our distracted age, rather an understanding of the place books or any art have—a vital and indispensable one, obviously, but not an exclusive one. In a busy life, those encounters with art perhaps take on even more importance; so they have to be worth it. So I have much more empathy now regarding the way in which a person conceives of herself as a reader, and loves novels, but might not want to read, you know, The Recognitions on a Tuesday evening after work. If you publish a book, it needs to be worthy of another person's time. That doesn't mean that it should be simple or easy or that everyone has to like it. (Personally, I think that nothing makes a book difficult to read more than bad prose.) But it should be necessary. And it should also be really fucking good.

And when I talk about necessary books, I'll say here that I think of your novel After Birth as absolutely that kind of necessary book. Its necessity, its raison d'être, just burns on every page.

TM: Thank you. I tried. And truth, there are not enough hours in the day or days in the year or years in a life for books that are not “worth it.” More and more I can intuit whether a book is going to bullshit me and waste my time from its opening pages, and I’ve grown shameless about not finishing books that hedge, books that are not tightly written, by writers who feel like mercenaries. There’s writing in service of the ego and then there’s writing in service of exploding the ego. Feast Days is so much the latter. It had me locked in from the first paragraph. You are so open and deliberate and clear and honest and funny and wry and arresting and self-aware. “Our naivety didn’t have political consequences. We had G.P.S. in our smartphones. I don’t think we were alcoholics.” It’s like the entire novel in microcosm. Gorgeous, and deceptively simple. Told from the P.O.V. of an American woman living in Sao Paolo. How did you arrive at this voice/structure/place, and what about the political implications you so shrewdly skewer on every page?

IM: The lines you just quoted, from the first page of the book, were among the earliest I wrote. The narrator's voice, her existence, was always there for me. This book began as a short story, something that's never happened to me previously as a writer—a short piece growing into something much longer—and it was because Emma's presence was so clear and large and immediate; she required more space to inhabit. At some point I thought of Saul Bellow’s description of writing The Adventures of Augie March—he has a great line about Augie March's voice coming down like rain and he, the writer, needing only to stand outside with a bucket—because I was so sure of Emma, but the experience of writing Feast Days wasn't like standing outside with a bucket. I still had to manufacture every sentence. What was new for me, though, was how immediately it was clear if the sentence I had just written belonged to Emma, or if it was an impostor sentence.

I started writing the book when I was still living in São Paulo. I arrived there a few months before the nationwide demonstrations in 2013, the events that in many ways really catalyzed the political drama that continues to consume Brazil—a president impeached, a former president imprisoned, a large number of congressmen indicted for various corruption-related offenses, just the complete demolition of the country's political class, all while crime and a general sense of instability permeate the major cities. And it's important to note that this is happening in a country whose democracy is still quite young, barely 30 years old, so you have people speaking nostalgically of military dictatorship, which is both extraordinary and not at all ahistorical. A lot of the most consequential political developments happened after I left, in 2015, and so the moment I was there to witness was preliminary—so interesting, because the future could still have gone in so many different directions.

Emma's voice is the main engine of the book. It's a woman's voice, of course, yet I've never written something that felt so natural. Somehow, writing as Emma allowed me to juxtapose registers—melancholy and biting, moody and ironic—in the way I do in conversation but have always resisted in writing. And, as you imply, she's direct. She doesn't say everything, and the lacunae, the things she doesn't say, occupy the book's white spaces and serve as frames around what is there. But when she does say something, she says it clearly. She doesn't use a lot of simile or metaphor. She notices, and she remarks on what she notices. She's laconic and sensitive at once. That's why I used the line from the Mark Strand poem as the epigraph. It's a great poem, "I Will Love the Twenty-First Century." It's filled with a kind of epochal, almost eschatological, emotion, yet it's told in this ridiculously cool, dry, bemused voice. And that's how Emma also thinks and talks.

TM: It strikes me as potentially problematic that one of the sharpest, deepest, most emotionally and intellectually enjoyable female narrators I’ve read recently was written by a man; probably a different reader would be up in arms about it, but I’m more interested in celebrating your accomplishment here. A good book is a good book is a good book, and this is a damn good book. The rest is noise. Though I confess I did wonder whether “Ian Mackenzie” might be a pen name. I’m very curious to hear about your day job. I admire the way it informs your writing as well as your perspective on writing. Feel free to tell me to fuck off.

IM: I certainly won't tell you to fuck off! And as for your statement of the problem, I’ll take it as a compliment. But you're right: it's not what's expected. And I wish I had some great, articulate account of being a male author writing in a woman's voice, but I don't. It was a voice—Emma's voice—that simply began to exist within me. That isn't to say that I wasn't cognizant of the appropriation; I was, intensely so. I'm aware of recent controversy regarding writers' appropriations of others' cultures, sexes, experiences, and my instinctual response is that, ultimately, any writer should have the freedom to write from any point of view. But that doesn't absolve writers from the sin of being tourists in others' lives for the sake of a text. There's lots of bad writing that results from a simplistic expropriation of exotic experience. If you're going to write from a vantage not your own, you have a lot of work to do, both interior and observational. That said, you can write a shitty memoir, too, so it's not as though writing only from your own experience guarantees success.

As for my day job, I'm a foreign service officer, a job that keeps me pretty far from the literary world, both physical and virtual. It's ultimately distinct from writing, but, just as any writer's day job or other experiences inform writing, it informs mine; for one thing, it brings me to other countries to live and work, and Feast Days grew out of my time living in Brazil. What I do as a foreign service officer is certainly useful to the concerns of a fiction writer: spend time in unfamiliar places, learn new languages, understand another country's culture and politics, speak with and come to know the people who live there. I'm grateful that my livelihood is independent of my writing, although it's a bit funny sometimes when the fact of writing comes up with my diplomatic colleagues, as it can't help but seem somewhat curious.

When I was living in Brazil and the large-scale protests began, in 2013, I was cognizant that I was witnessing something not merely local but arising from the warp and weft of human society in the 21st century. I couldn't help but think of DeLillo’s line from Mao II: "The future belongs to crowds." You see it everywhere, especially from the first months of the Arab Spring. It's the kind of thing, also, that engaging with the world as a foreign service officer deepens and complicates.

[millions_ad]

TM: Your distance from the literary world makes great sense, given your extraordinarily unselfconscious, intellectually and emotionally honest prose. The writing feels pure and fresh, unafraid of itself. And these tricky questions about appropriation remind me of something Geoff Dyer once said about how he’s not interested in fiction or memoir or nonfiction, he’s just interested in really good books. And incidentally, “Foreign Service Officer” is a great euphemism for “Novelist.” Diplomacy is the noble goal, but sometimes we’re outright spies, are we not?

On March 15, the politician and feminist activist Marielle Franco, who came out of the favelas to become this incredible leader, was assassinated in Rio. She had become a threat to the existing political system. Tens of thousands of people have taken to the streets to demand justice for her. One of the things Feast Days does so beautifully is to articulate the ways huge disparities in class and privilege define life in Brazil. Do you think things will change? Are they changing? What will it take? Are these hopelessly naïve questions?

IM: I like your alternative definition for "foreign service officer." Something I love about Brazil is its idiosyncratic tradition of diplomat writers—João Guimarães Rosa, Vinícius de Morães, João Cabral de Melo Neto. Osório Duque-Estrada, a poet who wrote the lyrics to Brazil's national anthem, was briefly a diplomat; and Clarice Lispector, of course, was a diplomat's wife.

To your question, I think things—all things—change slowly, when they change at all, and I resist being seduced by the narrative that the arc of history bends toward justice, because as much as I would like it to be true, and as much as the second half of the 20th century offers some consoling evidence, the arc of, say, the last 2,000 years of human history, or 4,000, shows that we're not on a straight, predictable, or necessarily upward path. In Brazil, where enormous street demonstrations have been a feature of life for the past five years, I don't think anyone would say the changes that have resulted are uncomplicatedly positive. The legacy of the 2013 manifestações is an ambiguous one, and frankly an unsettled one—there's more to this story yet to come. And the same has to be true of the outpouring of public anger following Marielle Franco's killing; perhaps it's ultimately a part of the same story, or perhaps it isn't. Brazilian society is riven by deep fissures along lines of race and class, great disparities that mark pretty much every 21st-century society but count particularly heavily in Brazil, where the wealthiest high-rises overlook the poorest favelas.

That's all a way of saying that your questions aren't naive at all, but they also aren't straightforward ones to answer. I mentioned DeLillo's line about crowds; that was something I thought about a lot during my time in São Paulo, as these protests turned into a recurring part of life. My main point of comparison was the Occupy protests in the United States, but what I saw in Brazil felt different. I don't mean to diminish Occupy, but I never had the sense that something fundamental would change because of it. In Brazil, it felt like something was changing, or might, but it also felt like—as Emma's husband notes at one point in the novel—the change to come wasn't something those petitioning for change could control. You see that now, with some activists and politicians blaming the manifestações—or the June Journeys, as they're known now—for leading indirectly to President Dilma Rousseff’s impeachment. In 2013, something came uncorked, and no one could predict the course of events to follow. This preoccupies Emma, a feeling she perceives in others of unearned sureness. She doesn't feel sure, even as the world demands that she feel sure of her opinions, her information, herself. Beyond the local and personal concerns of the novel, I wanted to situate Emma's story in this very specific 21st-century moment, when we're only just beginning to reckon with the meaning of crowds, both physical and virtual. It's the background hum of the novel. I don't need to say more about that here; there's plenty of opinion on that subject out there already for those who are inclined to consume it.

TM: Yes, yes, yes. This is precisely what I found so glorious and refreshing and truly hopeful in the most earnest sense about Emma’s voice: her refusal to be sure about anything. It’s so much harder to remain uncertain, to not know. Certainty can feel so cheap and shortsighted in general. She’s a stranger in a strange land, yes, but I got the sense that this is somehow constitutional for her. I love her for that. And it’s what makes her such a stellar narrator. She’s one of those characters I would follow anywhere.

Tell me what you’re reading, what you’ve been reading for the past few years, what fed into Feast Days, and what your head is in these days?

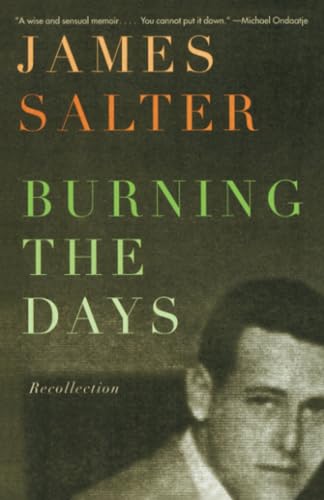

IM: Feast Days has two presiding spirits: Elizabeth Bishop and Joan Didion. Both of them are referred to in the course of the novel. Elizabeth Bishop, beyond what her poems mean to me, is inextricably bound up with the idea of the expatriate in Brazil. You can't think of Brazil and not think of her. Didion is a more global sort of influence for me, the rotating blades of her sentences, the reach of her eye, her precise sense of the dangers of exporting Americans to far-flung locales. She puts her finger on things. Elizabeth Hardwick, in particular her masterpiece Sleepless Nights, gave me a feeling early on for the possibilities of attrition in prose, for what a slim book can do. Perhaps no writer is more significant to me than James Salter. The title Feast Days is meant as a nod toward Light Years, and also Salter's memoir, Burning the Days. Graham Greene is another influence buried deep in the substrata of my sense of self as a writer. He's named in the book, too. I suppose that's to say I wear this stuff on my sleeve.

One of the finest recent novels I've read is another slim one, Valeria Luiselli’s Faces in the Crowd. Not only is it intellectually rich and entertaining, in the way of, say, Ben Lerner’s novels (another favorite), it slyly builds toward a resonant and devastating ending.

Outside of any obvious relation to Feast Days, Zia Haider Rahman’s In the Light of What We Know, which I read a few years ago, is, I think, one of the most extraordinary and accomplished novels written in English this century. It's a book I continue to think about as I contemplate the book I'm working on—which is in fact the book I was working on before even beginning Feast Days. Feast Days started life as procrastination, or distraction, from what I believed to be the main thing. I hope to turn back to that in earnest now.

Don't you find influence such a slippery thing to discuss? And performative—just like on Facebook, you can't avoid the attempt to curate the presentation of self through references and allusions. But of course it's fun, too, rattling on about the literature you love.

So I'll just also mention two books published this year that I loved, Lisa Halliday’s Asymmetry and Uzodinma Iweala’s Speak No Evil. Uzo is a good friend, and we were able to do a couple of events together around the publication of our novels. His book is like chamber music, dense and woven, all rhythmic voice and concentrated emotion.

TM: At the close of the novel, Emma ruminates on the ending of Rossellini’s Journey to Italy, in which a estranged married couple embrace "out of fear...not devotion." She judges this purported "happy ending" harshly: "their embrace is merely the postponement of something difficult." But there seems to me, in the book's final exhale, a note of grace, of resolution, of acquiescence to her life and her marriage and whatever life will bring. The possibility (or inevitability) of childbearing, in particular, haunts the novel. Does Emma live on for you? Do you have a sense of her trajectory beyond the pages of the book?

IM: Emma absolutely lives on for me! I said before how powerful the emergence of her voice in my mind was; that voice hasn't gone away. I think with pleasure of revisiting Emma, in the way that Roth or Updike or Richard Ford helplessly revisit their characters; but, as with Roth, I can imagine returning to Emma albeit in a nonlinear way—a mind and a voice that are Emma's, but imposed into different circumstances, not necessarily flowing directly from the events of Feast Days. I wonder about other possible lives for Emma. Other worlds at which to aim her particular eye.

A Year in Reading: Garth Risk Hallberg

This year, for the first time since I was 18, I suffered a bout of what you might call Reader's Block. It hit me in the spring and lasted about six weeks. The proximate cause was an excess of work, hunched hours in front of a computer that left me feeling like a jeweler's loupe was lodged in each eye. I'd turn to the door of my study -- Oh, God! An axe-wielding giant! No, wait: that's just my two year old, offering a mauled bagel. And because the only prose that doesn't look comparably distorted at that level of magnification belongs to E.B. White, Gertrude Stein, and whoever wrote the King James Bible, I mostly confined myself to the newspaper, when I read anything at all.

This hiatus from literature gave me a new compassion for people who glance up from smartphones to tell me they're too busy to read, and for those writers (students, mostly) who claim to avoid other people's work when they're working. Yet I found that for me, at least, the old programmer's maxim applies: Garbage In, Garbage Out. I mean this not just as someone with aesthetic aspirations, or pretensions, or whatever, but also as a human being.

The deeper cause of my reader's block, I can admit now, was my father's death at the end of May, after several years of illness. He was a writer, too; he'd published a novel when he was about the age I am now, and subsequently a travelogue. And maybe I had absorbed, over the years, some of his misapprehensions about what good writing might accomplish, vis-a-vis mortality; maybe I was now rebelling against the futility of the whole enterprise. I don't know. I do know that in the last weeks before he died, those weeks of no reading, I felt anxious, adrift, locked inside my grief.

Then in June, on some instinct to steer into the skid, I reached for Henderson the Rain King. It was the last of the major Bellows I hadn't read. I'd shied away partly for fear of its African setting, but mostly because it was the Saul Bellow book my father would always recommend. I'd say I was reading Humboldt's Gift, and he'd say, "But have you read Henderson the Rain King?" Or I'd say I was reading Middlemarch, and he'd say "Sure, but have you read Henderson the Rain King?" I'd say I was heavily into early Sonic Youth. "Okay, but there's this wonderful book..." There were times when I wondered if he'd actually read Henderson the Rain King, or if, having established that I hadn't read it, he saw it as a safe way to short-circuit any invitation into my inner life. And I suppose I was afraid that if I finally read Henderson and was unmoved, or worse, it would either confirm the hypothesis or demolish for all time my sense of my dad as a person of taste.

But of course the novel's mise-en-scène is a ruse (as Bellow well knew, never having been to Africa). Or if that still sounds imperialist, a dreamscape. Really, the whole thing is set at the center of a battered, lonely, yearning, and comical human heart. A heart that says, "I want, I want, I want." A heart that could have been my father's. Or my own. And though that heart doesn't get what it wants -- that's not its nature -- it gets something perhaps more durable. Midway through the novel, King Dahfu of the Wariri tries to talk a woebegone Henderson into hanging out with a lion:

"What can she do for you? Many things. First she is unavoidable. Test it, and you will find she is unavoidable. And this is what you need, as you are an avoider. Oh, you have accomplished momentous avoidances. But she will change that. She will make consciousness to shine. She will burnish you. She will force the present moment upon you. Second, lions are experiences. But not in haste. They experience with deliberate luxury...Then there are more subtle things, as how she leaves hints, or elicits caresses. But I cannot expect you to see this at first. She has much to teach you."

To which Henderson replies: "‘Teach? You really mean that she might change me.’"

"‘Excellent,'" the king says:

"Precisely. Change. You fled what you were. You did not believe you had to perish. Once more, and a last time, you tried the world. With a hope of alteration. Oh, do not be surprised by such a recognition."

The lion stuff in Henderson, like the tennis stuff in Infinite Jest, inclines pretty nakedly toward ars poetica. Deliberate luxury, burnished consciousness, a sense of inevitability -- aren't these a reader's hopes, too? And then: the deep recognition, the resulting change. Henderson the Rain King gave me all that, at the time when I needed it most. Then again, such a recognition is always surprising, because it's damn hard to come by. And so, though I'm already at 800 words here, I'd like to list some of my other best reading experiences of 2014 (the back half of which amounted to a long, post-Henderson binge). Maybe one of them will do for you what that lion did for me.

Light Years, by James Salter

Despite the eloquent advocacy of my Millions colleague Sonya Chung, I'd always had this idea of James Salter as some kind of Mandarin, a writer for other writers. But I read Light Years over two days in August, and found it a masterpiece. The beauty of Salter's prose -- and it is beautiful -- isn't the kind that comes from fussing endlessly over clauses, but the kind that comes from looking up from the page, listening hard to whatever's beyond. And what Light Years hears, as the title suggests, is time passing, the arrival and inevitable departure of everything dear to us. It is music like ice cracking, a river in the spring.

The Prime of Miss Jean Brodie, by Muriel Spark

I've long known I should read Muriel Spark, but it took the republication of some of her backlist (by New Directions) to get me off the fence. Spark shares with Salter a sublime detachment, an almost Olympian view of the passage of time. This latter seems to be her real subject in Miss Jean Brodie, inscribed even in the dazzling structure of the novel. But unlike Salter, Spark is funny. Really funny. Her reputation for mercilessness is not unearned, but the comedy here is deeper, I think. As in Jonathan Franzen's novels, it issues less from the exposure of flawed and unlikeable characters than from the author's warring impulses: to see them clearly, vs. to love them. Ultimately, in most good fiction, these amount to the same thing.

The Unbearable Lightness of Being, by Milan Kundera

This was a popular novel among grown-ups when I was a kid, and so I was pleasantly surprised to discover how stubborn and weird a work it is. And lovable for all that. Kundera keeps us at a peculiar distance from his protagonists, almost as if telling a fairy tale. Description is sparing. Plot is mostly sex. Also travel. At times, I had to remind myself which character was which. In a short story, this might be a liability. Yet somehow, over the length of the novel, through nuances of juxtaposition and patterning, Kundera manages to evoke states of feeling I've never seen on the page before. Political sadness. Emotional philosophy. The unbearable lightness of the title. All of this would seem to be as relevant in the U.S. in 2015 as in 1970s Prague.

The Infatuations, by Javier Marías

Hari Kunzru has captured, in a previous Year in Reading entry, how forbidding Javier Marías's novels can seem from a distance. (Though maybe this is true of all great stylists. Lolita, anyone?) Marías is a formidably cerebral writer, whose long sentences are like fugues: a theme is introduced, toyed with, pursued to another theme, put down, taken up again. None of this screams pleasure. But neither would a purely formal description of an Alfred Hitchcock movie. The tremendous pleasure of The Infatuations, Marías's most recent novel to appear in English, arrives from those most uncerebral places: plot, suspense, character. It's like a literary version of Strangers on a Train, cool formal mastery put to exquisitely visceral effect. "Don't open that door, Maria!" The Infatuations is the best new novel I read all year; I knew within the first few pages that I would be reading every book Mariás has written.

All the Birds, Singing, by Evie Wyld

This haunting, poetic novel manages to convey in a short space a great deal about compulsion and memory and the human capacity for good and evil. Wyld's narrator, Jake, is one of the most distinctive and sympathetic heroines in recent literature, a kind of Down Under Huck Finn. Her descriptions of the Australian outback are indelible. And the novel's backward-and-forward form manages a beautiful trick: it simultaneously dramatizes the effects of trauma and attends to our more literary hungers: for form, for style. It reminded me forcefully of another fine book that came out of the U.K. this year, Eimear McBride's A Girl is a Half-Formed Thing.

Wolf Hall and Bring Up the Bodies, by Hilary Mantel

I'd be embarrassed at my lateness to the Thomas Cromwell saga, were I not so glad to have finally made it. Mantel's a serious enough historical novelist not to shy away from those conventions of the genre that usually turn me off; the deliberate pacing of her trilogy-in-progress requires some getting used to. But more than a chronicler, Mantel is a novelist, full-stop. She excels at pretty much everything, and plays the long game brilliantly. By the time you get into the intrigues of Bring Up the Bodies, you're flying so fast you hardly notice the beautiful calibration of the prose, or the steady deepening of the psychology, or the big thoughts the novel is thinking about pragmatism and Englishness and gender and the mystery of personality.

Dispatches, by Michael Herr

If you took the horrific public-burning scene from Wolf Hall, multiplied that by 100, put those pages in a hot-boxed Tomahawk piloted by Dr. Strangelove, and attempted to read them over the blare of the Jefferson Airplane, you'd end up with something like Dispatches. It is simultaneously one of the greatest pieces of New Journalism I've ever read and one of the greatest pieces of war writing. Indeed, each achievement enables the other. The putatively embedded journalism of our own wars already looks dated by comparison. Since the publication of Dispatches in 1977, Herr's output has been slender, but I'd gladly read anything he wrote.

White Girls, by Hilton Als

This nonfiction collection casts its gaze all over the cultural map, from Flannery O'Connor to Michael Jackson, yet even more than most criticism, it adds up to a kind of diffracted autobiography. The longest piece in the book is devastating, the second-longest tough to penetrate, but this unevenness speaks to Als's virtues as an essayist. His sentences have a quality most magazine writing suffocates beneath a veneer of glibness: the quality of thinking. That is, he seems at once to have a definite point-of-view, passionately held, and to be very much a work in progress. It's hard to think of higher praise for a critic.

Utopia or Bust, by Benjamin Kunkel

This collection of sterling essays (many of them from the London Review of Books) covers work by David Graeber, Robert Brenner, Slavoj Zizek, and others, offering a state-of-the-union look at what used to be called political economy -- a nice complement to the research findings of Thomas Piketty. Kunkel is admirably unembarrassed by politics as such, and is equally admirable as an autodidact in the field of macroeconomics. He synthesizes from his subjects one of the more persuasive accounts you'll read about how we got into the mess we're in. And his writing has lucidity and wit. Of Fredric Jameson, for example, he remarks: "Not often in American writing since Henry James can there have been a mind displaying at once such tentativeness and force."

The Origin of the Brunists, by Robert Coover

The publication this spring of a gargantuan sequel, The Brunist Day of Wrath, gave me an excuse to go back and read Coover's first novel, from 48 years ago. As a fan of his midcareer highlights, The Public Burning and Pricksongs and Descants, I was expecting postmodern glitter. Instead I got something closer to William Faulkner: tradition and modernity collide in a mining town beset by religious fanaticism. Yet with the attenuation of formal daring comes an increased access to Coover's capacity for beauty, in which he excels many of his well-known peers. Despite its (inspired) misanthropy, this is a terrific novel. I couldn't help wishing, as I did with much of what I read this year, that my old man was still around, that I might recommend it to him, and so repay the debt.

More from A Year in Reading 2014

Don't miss: A Year in Reading 2013, 2012, 2011, 2010, 2009, 2008, 2007, 2006, 2005

The good stuff: The Millions' Notable articles

The motherlode: The Millions' Books and Reviews

Like what you see? Learn about 5 insanely easy ways to Support The Millions, and follow The Millions on Twitter, Facebook, Tumblr.

A Year in Reading: Matt Bell