1.

Recently, for the fourth or fifth time in my life, I started trying to read James Salter‘s A Sport and a Pastime. I bought my copy many years ago, after falling in love with his story collections and enjoying Light Years, probably his best-known novel. A Sport and a Pastime, though not obscure, has a whiff of the occult about it, with its hazy voyeuristic sex and a title taken from the Koran. It is commonly and unironically referred to as an “erotic masterpiece.” Writing for The New York Times Review of Books, Reynolds Price said, “Of living novelists, none has produced a novel I admire more than A Sport and a Pastime…it’s as nearly perfect as any American fiction I know.”

Despite these points of interest and an agreeable running length of right around 200 pages, over two decades, I’ve found myself consistently stymied by something in this novel. I can still clearly remember the thrill of finding it at a used bookstore (it was, I believe, out of print at the time, or at any rate not widely available), taking it home, cracking it open along with a beer, and…not reading it.

Despite these points of interest and an agreeable running length of right around 200 pages, over two decades, I’ve found myself consistently stymied by something in this novel. I can still clearly remember the thrill of finding it at a used bookstore (it was, I believe, out of print at the time, or at any rate not widely available), taking it home, cracking it open along with a beer, and…not reading it.

This has been my experience with A Sport and a Pastime, our relationship, so to speak, over the last two decades. Maybe it’s the strange narrative setup, the unnamed narrator employed mostly as a camera for the erotic exploits of the central couple. Maybe it’s the slowness of the plot. More likely, I think, it’s something wrong with me.

There is a type of book, I find, that falls in this category: books that resist you. This is different from books you think are bad, or books you don’t want to read. These are books you want to read, but for some reason are unable to. These are books that, if anything, you somehow fail, not being up to the task.

The obverse of this is the kind of book you helplessly return to again and again. Some personal examples: The Patrick Melrose cycle, Disgrace, A House for Mr. Biswas, The Talented Mr. Ripley, Flannery O’Connor’s The Collected Stories, The Big Sleep, Pride and Prejudice, Madame Bovary. These are books that my taste and intellect, such as they are, somehow notch into like teeth into a greater gear. Sometimes you outgrow these books, as I feel I have with, say, Kurt Vonnegut’s corpus, but by and large these are books that I have read throughout my adulthood and continue getting different things out of with each read.

I’m not sure this is a good thing. In a way, this kind of reading preserves a personal stasis, forever reconfirming your excellent taste in literature, always agreeing with you. They are the yes-men of your library—in reading, as in life, it is good to find people who will tell you no: No, maybe you are not smart enough for this; no, you are not entitled to an immediate endorphin release upon opening me up; no, you cannot read me.

3.

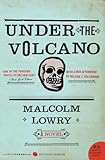

Another book of the former type: Malcolm Lowry’s Under the Volcano. This is an especially irksome one, a novel I’ve been attracted to for years, then repulsed by every time I open the cover. My experience with this kind of book does feel, in its way, analogous to a certain kind of romantic flirtation, a pas de deux of advance and retreat—never quite enough advance to win the book’s affection; never quite enough retreat to finally put me off. I have long been drawn to The Volcano and Lowry’s shared mythos: suicidal alcoholism in a hot country. I’m intrigued by its aura and stature as one of the greatest books of the century. I want to read it.

But man, that first chapter—I’ve read it several times and never made it any further. From memory: the initial, oblique conversation between Laruelle and Dr. Vigil (okay, I looked these up) on the hotel balcony as they sip anis and gaze out at the titular volcano; the references to the Consul, Fermin (who I am aware, theoretically, will at some point become the actual main character), and shared recollections of his misbehavior and disappearance; Laruelle’s interminable saunter down the hill and into town; an equally protracted sojourn at a bar that, again, if memory serves, is strangely connected to a movie theater. There, Laruelle is given a book for some reason. Other things happen, or don’t. My memory of that chapter feels consistent with the mode in which I have most frequently encountered it: falling asleep in bed. Which is to say that the first part is most vivid, and, as it goes on, the lights grow dimmer and the enterprise seems to begin repeating itself.

4.

But this is clearly user error. Maybe it’s a coincidence, but I notice, with both Under the Volcano and A Sport and a Pastime, a personal difficulty with books that dwell too long in the perspective of a peripheral character. No matter how good the language and description—and the language and description in Under the Volcano are, of course, very good—at a certain point I want it to get a move on. The truth probably is that I am not an especially good, or patient, reader. Maybe good compared to the average casual reader, but not compared to many other writers and academics I know, who seem to omnivorously inhale all manner of book no matter how difficult or slow, like woodchippers dispatching balsa.

The truth probably is that my normal reading taste level lands somewhere just north of middlebrow. I have read Ulysses (and is there a more loathsome sentence to type than this?—the literary equivalent of mentioning your SAT score). But I skipped large swaths of the especially difficult chapters like “Proteus” and “Oxen of the Sun.” My highbrow taste is defined by a narrow niche of books that are well-written and also, for lack of a better word, fun.

Nabokov’s novels, for example—as strenuously modern and well-written as they are, they also move. They are not boring. The reader’s attention is rewarded like a good dog, receiving periodic treats for trotting along behind the master. “Fun” is a strange descriptor to apply to a book about pedophilia, but in spite of its subject matter, Lolita is, well, a pretty rollicking read (really, this is the novel’s perverse central project, to coax a reader into an aesthetic pleasure that mirrors, horribly, Humbert’s), jammed with the darkest comedy, suspense, wordplay, twists, turns, and the climactic ending to end all climactic endings. It is fun, as is Pnin, as is Pale Fire. Even early juvenilia like The Eye keeps you interested.

5.

Interestingness, is, of course, in the eye of the beholder. But would it be completely unfair to say that a large swath of what we consider literary fiction is, by its nature and/or by design, uneventful? My Struggle is an obvious recent example—the first 200 pages of Book One are the story of the time young Karl Ove and a friend tried (spoiler alert: successfully) to get a case of beer to a high school party. Later, he devotes dozens of pages to the description of cleaning a bathroom.

Knausgaard’s work may provide an extreme example, but it remains generally true that in what we consider highbrow literary fiction, plotlessness often serves as a genre and status marker. Presumably this has something to do with a semi-consciously received idea of literary fiction being realistic fiction, and reality being uneventful. Brian Cox, portraying the screenwriting coach Robert McKee in Adaptation, had this to say on the matter:

Nothing happens in the world? Are you out of your fucking mind? People are murdered every day. There’s genocide, war, corruption. Every fucking day, somewhere in the world, somebody sacrifices his life to save someone else. Every fucking day, someone, somewhere takes a conscious decision to destroy someone else. People find love, people lose it. For Christ’s sake, a child watches her mother beaten to death on the steps of a church. Someone goes hungry. Somebody else betrays his best friend for a woman. If you can’t find that stuff in life, then you, my friend, don’t know crap about life!

My Struggle received overwhelming critical praise for its rejection of that stuff and for its strenuous, almost ostentatious, dramatization of the banal and prosaic—all of the bits that typically get cut out of plot-driven fiction. Zadie Smith, praising the books, said, “Like Warhol, he makes no attempt to be interesting.” The intellectual enshrinement of non-event is worth considering on its merits for a moment. It might be argued that this high literary conception of real life as a frictionless enactment of societal rituals, unconscious consumerism, and media absorption is essentially a safe, bourgeois version of reality, and that plot-free literary fiction aestheticizes that principle of non-event. And so it might further be argued that literature that tests a reader’s ability to endure boredom and plotlessness is, on some level, testing the degree of that reader’s integration into the late capitalist fantasy of a perfectly isolated and insulated existence just as much as a writer like James Patterson affirms that integration by the obverse means of testing a reader’s willingness to accept product as art. The extremes of event and non-event both affirm this version.

6.

Then again, maybe (probably) this is bullshit, rigging up an objective rationale for personal taste. And besides, I can think of so many counterexamples—books in which nothing much happens that I adore. The Outline trilogy, for example, or Ben Lerner’s Leaving the Atocha Station. I would listen to Faye listening to people until the end of time; I’d follow Lerner’s valium-popping liar Adam Gordon to the ends of the world. In the end, it probably just comes down to something ineffable and mysterious in the writing. That connection between author and reader, the partnership and compact that must occur, something in the handshake that slips, that doesn’t quite hold.