Mentioned in:

A Year in Reading: 2024

Welcome to the 20th (!) installment of The Millions' annual Year in Reading series, which gathers together some of today's most exciting writers and thinkers to share the books that shaped their year. YIR is not a collection of yearend best-of lists; think of it, perhaps, as an assemblage of annotated bibliographies. We've invited contributors to reflect on the books they read this year—an intentionally vague prompt—and encouraged them to approach the assignment however they choose.

In writing about our reading lives, as YIR contributors are asked to do, we inevitably write about our personal lives, our inner lives. This year, a number of contributors read their way through profound grief and serious illness, through new parenthood and cross-country moves. Some found escape in frothy romances, mooring in works of theology, comfort in ancient epic poetry. More than one turned to the wisdom of Ursula K. Le Guin. Many describe a book finding them just when they needed it.

Interpretations of the assignment were wonderfully varied. One contributor, a music critic, considered the musical analogs to the books she read, while another mapped her reads from this year onto constellations. Most people's reading was guided purely by pleasure, or else a desire to better understand events unfolding in their lives or larger the world. Yet others centered their reading around a certain sense of duty: this year one contributor committed to finishing the six Philip Roth novels he had yet to read, an undertaking that he likens to “eating a six-pack of paper towels.” (Lucky for us, he included in his essay his final ranking of Roth's oeuvre.)

The books that populate these essays range widely, though the most commonly noted title this year was Tony Tulathimutte’s story collection Rejection. The work of newly minted National Book Award winner Percival Everett, particularly his acclaimed novel James, was also widely read and written about. And as the genocide of Palestinians in Gaza enters its second year, many contributors sought out Isabella Hammad’s searing, clear-eyed essay Recognizing the Stranger.

Like so many endeavors in our chronically under-resourced literary community, Year in Reading is a labor of love. The Millions is a one-person editorial operation (with an invaluable assist from SEO maven Dani Fishman), and producing YIR—and witnessing the joy it brings contributors and readers alike—has been the highlight of my tenure as editor. I’m profoundly grateful for the generosity of this year’s contributors, whose names and entries will be revealed below over the next three weeks, concluding on Wednesday, December 18. Be sure to subscribe to The Millions’ free newsletter to get the week’s entries sent straight to your inbox each Friday.

—Sophia Stewart, editor

Becca Rothfeld, author of All Things Are Too Small

Carvell Wallace, author of Another Word for Love

Charlotte Shane, author of An Honest Woman

Brianna Di Monda, writer and editor

Nell Irvin Painter, author of I Just Keep Talking

Carrie Courogen, author of Miss May Does Not Exist

Ayşegül Savaş, author of The Anthropologists

Zachary Issenberg, writer

Tony Tulathimutte, author of Rejection

Ann Powers, author of Traveling: On the Path of Joni Mitchell

Lidia Yuknavitch, author of Reading the Waves

Nicholas Russell, writer and critic

Daniel Saldaña París, author of Planes Flying Over a Monster

Lili Anolik, author of Didion and Babitz

Deborah Ghim, editor

Emily Witt, author of Health and Safety

Nathan Thrall, author of A Day in the Life of Abed Salama

Lena Moses-Schmitt, author of True Mistakes

Jeremy Gordon, author of See Friendship

John Lee Clark, author of Touch the Future

Ellen Wayland-Smith, author of The Science of Last Things

Edwin Frank, publisher and author of Stranger Than Fiction

Sophia Stewart, editor of The Millions

A Year in Reading Archives: 2023, 2022, 2021, 2020, 2019, 2018, 2017, 2016, 2015, 2014, 2013, 2011, 2010, 2009, 2008, 2007, 2006, 2005

The Great Fall 2024 Book Preview

With the arrival of autumn comes a deluge of great books. Here you'll find a sampling of new and forthcoming titles that caught our eye here at The Millions, and that we think might catch yours, too. Some we’ve already perused in galley form; others we’re eager to devour based on their authors, plots, or subject matters. We hope your next fall read is among them.

—Sophia Stewart, editor

October

Season of the Swamp by Yuri Herrera, tr. Lisa Dillman [F]

What it is: An epic, speculative account of the 18 months that Benito Juárez spent in New Orleans in 1853-54, years before he became the first and only Indigenous president of Mexico.

Who it's for: Fans of speculative history; readers who appreciate the magic that swirls around any novel set in New Orleans. —Claire Kirch

The Black Utopians by Aaron Robertson [NF]

What it is: An exploration of Black Americans' pursuit and visions of utopia—both ideological and physical—that spans the Reconstruction era to the present day and combines history, memoir, and reportage.

Who it's for: Fans of Saidiya Hartman's Wayward Lives, Beautiful Experiments and Kristen R. Ghodsee's Everyday Utopia. —Sophia M. Stewart

The Third Realm by Karl Ove Knausgaard, tr. Martin Aitken [F]

What it is: The third installment in Knausgaard's Morning Star series, centered on the appearance of a mysterious new star in the skies above Norway.

Who it's for: Real Knausgaard heads only—The Wolves of Eternity and Morning Star are required reading for this one. —SMS

Brown Women Have Everything by Sayantani Dasgupta [NF]

What it is: Essays on the contradictions and complexities of life as an Indian woman in America, probing everything from hair to family to the joys of travel.

Who it's for: Readers of Durga Chew-Bose, Erika L. Sánchez, and Tajja Isen. —SMS

The Plot Against Native America by Bill Vaughn [F]

What it is: The first narrative history of Native American boarding schools— which aimed "civilize" Indigenous children by violently severing them from their culture— and their enduring, horrifying legacy.

Who it's for: Readers of Ned Blackhawk and Kathleen DuVal. —SMS

The Mighty Red by Louise Erdrich [F]

What it is: Erdrich's latest novel set in North Dakota's Red River Valley is a tale of the intertwined lives of ordinary people striving to survive and even thrive in their rural community, despite environmental upheavals, the 2008 financial crisis, and other obstacles.

Who it's for: Readers of cli-fi; fans of Linda LeGarde Grover and William Faulkner. —CK

The Position of Spoons by Deborah Levy [NF]

What it is: The second book from Levy in as many years, diverging from a recent streak of surrealist fiction with a collection of essays marked by exceptional observance and style.

Who it's for: Close lookers and the perennially curious. —John H. Maher

The Bog Wife by Kay Chronister [F]

What it's about: The Haddesley family has lived on the same West Virginia bog for centuries, making a supernatural bargain with the land—a generational blood sacrifice—in order to do so—until an uncovered secret changes everything.

Who it's for: Readers of Karen Russell and Jeff VanderMeer; anyone who has ever used the phrase "girl moss." —SMS

The Great When by Alan Moore [F]

What it's about: When an 18-year old book reseller comes across a copy of a book that shouldn’t exist, it threatens to upend not just an already post-war-torn London, but reality as we know it.

Who it's for: Anyone looking for a Sherlock Holmes-style mystery dipped in thaumaturgical psychedelia. —Daniella Fishman

The Message by Ta-Nehisi Coates [NF]

What it's about: One of our sharpest critical thinkers on social justice returns to nonfiction, nearly a decade after Between the World and Me, visiting Dakar, to contemplate enslavement and the Middle Passage; Columbia, S.C., as a backdrop for his thoughts on Jim Crow and book bans; and the Israeli-occupied West Bank, where he sees contemporary segregation in the treatment of Palestinians.

Who it’s for: Fans of James Baldwin, George Orwell, and Angela Y. Davis; readers of Nikole Hannah-Jones’s The 1619 Project and Isabel Wilkerson’s Caste, to name just a few engagements with national and racial identity. —Nathalie op de Beeck

Abortion by Jessica Valenti [NF]

What it is: Columnist and memoirist Valenti, who tracks pro-choice advocacy and attacks on the right to choose in her Substack, channels feminist rage into a guide for freedom of choice advocacy.

Who it’s for: Readers of Robin Marty’s The New Handbook for a Post-Roe America, #ShoutYourAbortion proponents, and followers of Jennifer Baumgartner’s [I Had an Abortion] project. —NodB

Gifted by Suzuki Suzumi, tr. Allison Markin Powell [F]

What it's about: A young sex worker in Tokyo's red-light district muses on her life and recounts her abusive mother's final days, in what is Suzuki's first novel to be translated into English.

Who it's for: Readers of Susan Boyt and Mieko Kanai; fans of moody, introspective fiction; anyone with a fraught relationship to their mother. —SMS

Childish Literature by Alejandro Zambra, tr. Megan McDowell [F]

What it is: A wide-ranging collection of stories, essays, and poems that explore childhood, fatherhood, and family.

Who it's for: Fans of dad lit (see: Lucas Mann's Attachments, Keith Gessen's Raising Raffi, Karl Ove Knausgaard's seasons quartet, et al). —SMS

Books Are Made Out of Books ed. Michael Lynn Crews [NF]

What it is: A mining of the archives of the late Cormac McCarthy with a focus on the famously tight-lipped author's literary influences.

Who it's for: Anyone whose commonplace book contains the words "arquebus," "cordillera," or "vinegaroon." —JHM

Slaveroad by John Edgar Wideman [F]

What it is: A blend of memoir, fiction, and history that charts the "slaveroad" that runs through American history, spanning the Atlantic slave trade to the criminal justice system, from the celebrated author of Brothers and Keepers.

Who it's for: Fans of Clint Smith and Ta-Nehisi Coates. —SMS

Linguaphile by Julie Sedivy [NF]

What it's about: Linguist Sedivy reflects on a life spent loving language—its beauty, its mystery, and the essential role it plays in human existence.

Who it's for: Amateur (or professional) linguists; fans of the podcast A Way with Words (me). —SMS

An Image of My Name Enters America by Lucy Ives [NF]

What it is: A collection of interrelated essays that connect moments from Ives's life to larger questions of history, identity, and national fantasy,

Who it's for: Fans of Ives, one of our weirdest and most wondrous living writers—duh; anyone with a passing interest in My Little Pony, Cold War–era musicals, or The Three Body Problem, all of which are mined here for great effect. —SMS

Women's Hotel by Daniel Lavery [F]

What it is: A novel set in 1960s New York City, about the adventures of the residents of a hotel providing housing for young women that is very much evocative of the real-life legendary Barbizon Hotel.

Who it's for: Readers of Mary McCarthy's The Group and Rona Jaffe's The Best of Everything. —CK

The World in Books by Kenneth C. Davis [NF]

What it is: A guide to 52 of the most influential works of nonfiction ever published, spanning works from Plato to Ida B. Wells, bell hooks to Barbara Ehrenreich, and Sun Tzu to Joan Didion.

Who it's for: Lovers of nonfiction looking to cover their canonical bases. —SMS

Blue Light Hours by Bruna Dantas Lobato [F]

What it's about: Through the emanating blue-glow of their computer screens, a mother and daughter, four-thousand miles apart, find solace and loneliness in their nightly Skype chats in this heartstring-pulling debut.

Who it's for: Someone who needs to be reminded to CALL YOUR MOTHER! —DF

Riding Like the Wind by Iris Jamahl Dunkle [NF]

What it is: The biography of Sanora Babb, a contemporary of John Steinbeck's whose field notes and interviews with Dust Bowl migrants Steinbeck relied upon to write The Grapes of Wrath.

Who it's for: Steinbeck fans and haters alike; readers of Kristin Hannah's The Four Winds and the New York Times Overlooked column; anyone interested in learning more about the Dust Bowl migrants who fled to California hoping for a better life. —CK

Innie Shadows by Olivia M. Coetzee [F]

What it is: a work of crime fiction set on the outskirts of Cape Town, where a community marred by violence seeks justice and connection; also the first novel to be translated from Kaaps, a dialect of Afrikaans that was until recently only a spoken language.

Who it's for: fans of sprawling, socioeconomically-attuned crime dramas a la The Wire. —SMS

Dorothy Parker in Hollywood by Gail Crowther [NF]

What it is: A history of the famous wit—and famous New Yorker—in her L.A. era, post–Algonquin Round Table and mid–Red Scare.

Who it's for: Owners of a stack of hopelessly dog-eared Joan Didion paperbacks. —JHM

The Myth of American Idealism by Noam Chomsky and Nathan J. Robinson [NF]

What it is: A potent critique of the ideology behind America's foreign interventions and its status as a global power, and an treatise on how the nation's hubristic pursuit of "spreading democracy" threatens not only the delicate balance of global peace, but the already-declining health of our planet.

Who it's for: Chomskyites; policy wonks and casual critics of American recklessness alike. —DF

Mysticism by Simon Critchley [NF]

What it is: A study of mysticism—defined as an experience, rather than religious practice—by the great British philosopher Critchley, who mines music, poetry, and literature along the way.

Who it's for: Readers of John Gray, Jorge Luis Borges, and Simone Weil. —SMS

Q&A by Adrian Tomine [NF]

What it is: The Japanese American creator of the Optic Nerve comic book series for D&Q, and of many a New Yorker cover, shares his personal history and his creative process in this illustrated unburdening.

Who it’s for: Readers of Tomine’s melancholic, sometimes cringey, and occasionally brutal collections of comics short stories including Summer Blonde, Shortcomings, and Killing and Dying. —NodB

Sonny Boy by Al Pacino [NF]

What it is: Al Pacino's memoir—end of description.

Who it's for: Cinephiles; anyone curious how he's gonna spin fumbling Diane Keaton. —SMS

Seeing Baya by Alice Kaplan [NF]

What it is: The first biography of the enigmatic and largely-forgotten Algerian artist Baya Mahieddine, who first enchanted midcentury Paris as a teenager.

Who it's for: Admirers of Leonora Carrington, Hilma af Klint, Frida Kahlo, and other belatedly-celebrated women painters. —SMS

Absolution by Jeff VanderMeer [F]

What it is: A surprise return to the Area X, the stretch of unforbidding and uncanny coastline in the hit Southern Reach trilogy.

Who it's for: Anyone who's heard this song and got the reference without Googling it. —JHM

The Four Horsemen by Nick Curtola [NF]

What it is: The much-anticipated cookbook from the team behind Brooklyn's hottest restaurant (which also happens to be co-owned by James Murphy of LCD Soundsystem).

Who it's for: Oenophiles; thirty-somethings who live in north Williamsburg (derogatory). —SMS

Seeing Further by Esther Kinsky, tr. Caroline Schmidt [F]

What it's about: An unnamed German woman embarks on the colossal task of reviving a cinema in a small Hungarian village.

Who it's for: Fans of Jenny Erpenbeck; anyone charmed by Cinema Paradiso (not derogatory!). —SMS

Ripcord by Nate Lippens [NF]

What it's about: A novel of class, sex, friendship, and queer intimacy, written in delicious prose and narrated by a gay man adrift in Milwaukee.

Who it's for: Fans of Brontez Purnell, Garth Greenwell, Alexander Chee, and Wayne Koestenbaum. —SMS

The Use of Photography by Annie Ernaux and Marc Marie, tr. Alison L. Strayer [NF]

What it's about: Ernaux's love affair with Marie, a journalist, while she was undergoing treatment for cancer, and their joint project to document their romance.

Who it's for: The Ernaux hive, obviously; readers of Sontag's On Photography and Janet Malcolm's Still Pictures. —SMS

Nora Ephron at the Movies by Ilana Kaplan [NF]

What it is: Kaplan revisits Nora Ephron's cinematic watersheds—Silkwood, Heartburn, When Harry Met Sally, You've Got Mail, and Sleepless in Seattle—in this illustrated book. Have these iconic stories, and Ephron’s humor, weathered more than 40 years?

Who it’s for: Film history buffs who don’t mind a heteronormative HEA; listeners of the Hot and Bothered podcast; your coastal grandma. —NodB

[millions_email]

The Philosophy of Translation by Damion Searls [NF]

What it is: A meditation on the act and art of translation by one of today's most acclaimed practitioners, best known for his translations of Fosse, Proust, et al.

Who it's for: Regular readers of Words Without Borders and Asymptote; professional and amateur literary translators alike. —SMS

Salvage by Dionne Brand

What it is: A penetrating reevaluation of the British literary canon and the tropes once shaped Brand's reading life and sense of self—and Brand’s first major work of nonfiction since her landmark A Map to the Door of No Return.

Who it's for: Readers of Christina Sharpe's Ordinary Notes and Elizabeth Hardwick's Seduction and Betrayal. —SMS

Masquerade by Mike Fu [F]

What it's about: Housesitting for an artist friend in present-day New York, Meadow Liu stumbles on a novel whose author shares his name—the first of many strange, haunting happenings that lead up to the mysterious disappearance of Meadow's friend.

Who it's for: fans of Ed Park and Alexander Chee. —SMS

November

The Beggar Student by Osamu Dazai, tr. Sam Bett [F]

What it is: A novella in the moody vein of Dazai’s acclaimed No Longer Human, following the 30-something “fictional” Dazai into another misadventure spawned from a hubristic spat with a high schooler.

Who it's for: Longtime readers of Dazai, or new fans who discovered the midcentury Japanese novelist via TikTok and the Bungo Stray Dogs anime. —DF

In Thrall by Jane DeLynn [F]

What it is: A landmark lesbian bildungsroman about 16-year-old Lynn's love affair with her English teacher, originally published in 1982.

Who it's for: Fans of Joanna Russ's On Strike Against God and Edmund White's A Boy's Own Story —SMS

Washita Love Child by Douglas Kent Miller [NF]

What it is: The story of Jesse Ed Davis, the Indigenous musician who became on of the most sought after guitarists of the late '60s and '70s, playing alongside B.B. King, Bob Dylan, John Lennon, and more.

Who it's for: readers of music history and/or Indigenous history; fans of Joy Harjo, who wrote the foreword. —SMS

Set My Heart on Fire by Izumi Suzuki, tr. Helen O'Horan [F]

What it is: Gritty, sexy, and wholly rock ’n’ roll, Suzuki’s first novel translated into English (following her story collection, Hit Parade of Tears) follows 20-year-old Izumi navigating life, love, and music in the underground scene in '70s Japan.

Who it's for: Fans of Meiko Kawakami, Ursula K. Le Guin, and Marlowe Granados's Happy Hour. —DF

Didion & Babitz by Lili Anolik [NF]

What it is: A dual portrait of Joan Didion and Eve Babitz, who are so often compared to—and pitted against—each other on the basis of their mutual Los Angeles milieu.

Who it's for: Fans or haters of either writer (the book is fairly pro-Babitz, often at Didion's expense); anyone who has the Lit Hub Didion tote bag. —SMS

The Endless Refrain by David Rowell [NF]

What it's about: How the rise of music streaming, demonitizing of artist revenue, and industry tendency toward nostalgia have laid waste to the musical landscape, and the future of music culture.

Who it's for: Fans of Kyle Chayka, Spence Kornhaber, and Lindsay Zoladz. —SMS

Every Arc Bends Its Radian by Sergio De La Pava [F]

What it is: A mind- and genre-bending detective story set in Cali, Colombia, that blends high-stakes suspense with rigorous philosophy.

Who it's for: Readers of Raymond Chandler, Thomas Pynchon, and Jules Verne. —SMS

Something Close to Nothing by Tom Pyun [F]

What it’s about: At the airport with his white husband Jared, awaiting a flight to Cambodia to meet the surrogate mother carrying their adoptive child-to-be, Korean American Wynn decides parenthood isn't for him, and bad behavior ensues.

Who it’s for: Pyun’s debut is calculated to cut through saccharine depictions of queer parenthood—could pair well with Torrey Peters’s Detransition, Baby. —NodB

Rosenfeld by Maya Kessler [F]

What it is: Kessler's debut—rated R for Rosenfeld—follows one Noa Simmons through the tumultuous and ultimately profound power play that is courting (and having a lot of sex with) the titular older man who soon becomes her boss.

Who it's for: Fans of Sex and the City, Raven Leilani’s Luster, and Coco Mellor’s Cleopatra and Frankenstein. —DF

Lazarus Man by Richard Price [F]

What it is: The former The Wire writer offers yet another astute chronicle of urban life, this time of an ever-changing Harlem.

Who it's for: Fans of Colson Whitehead's Crook Manifesto and Paul Murray's The Bee Sting—and, of course, The Wire. —SMS

Stranger Than Fiction by Edwin Frank [NF]

What it is: An astute curveball of a read on the development and many manifestations of the novel throughout the tumultuous 20th century.

Who it's for: Readers who look at a book's colophon before its title. —JHM

Letters to His Neighbor by Marcel Proust, tr. Lydia Davis

What it is: A collection of Proust’s tormented—and frequently hilarious—letters to his noisy neighbor which, in a diligent translation from Davis, stand the test of time.

Who it's for: Proust lovers; people who live below heavy-steppers. —DF

Context Collapse by Ryan Ruby [NF]

What it is: A self-proclaimed "poem containing a history of poetry," from ancient Greece to the Iowa Workshop, from your favorite literary critic's favorite literary critic.

Who it's for: Anyone who read and admired Ruby's titanic 2022 essay on The Waste Land; lovers of poetry looking for a challenge. —SMS

How Sondheim Can Change Your Life by Richard Schoch [NF]

What it's about: Drama professor Schoch's tribute to Stephen Sondheim and the life lessons to be gleaned from his music.

Who it's for: Sondheim heads, former theater kids, end of list. —SMS

The Serviceberry by Robin Wall Kimmerer [NF]

What it is: 2022 MacArthur fellow and botanist Kimmerer, an enrolled member of the Citizen Potawatomi Nation, (re)introduces audiences to a flowering, fruiting native plant beloved of foragers and gardeners.

Who it’s for: The restoration ecologist in your life, along with anyone who loved Braiding Sweetgrass and needs a nature-themed holiday gift. —NodB

My Heart Belongs in an Empty Big Mac Container Buried Beneath the Ocean Floor by Homeless [F]

What it is: A pseudonymous, tenderly comic novel of blue whales and Golden Arches, mental illness and recovery.

Who it's for: Anyone who finds Thomas Pynchon a bit too staid. —JHM

Yoke and Feather by Jessie van Eerden [NF]

What it's about: Van Eerden's braided essays explore the "everyday sacred" to tease out connections between ancient myth and contemporary life.

Who it's for: Readers of Courtney Zoffness's Spilt Milk and Jeanna Kadlec's Heretic. —SMS

Camp Jeff by Tova Reich [F]

What it's about: A "reeducation" center for sex pests in the Catskills, founded by one Jeffery Epstein (no, not that one), where the dual phenomena of #MeToo and therapyspeak collide.

Who it's for: Fans of Philip Roth and Nathan Englander; cancel culture skeptics. —SMS

Selected Amazon Reviews by Kevin Killian [NF]

What it is: A collection of 16 years of Killian’s funniest, wittiest, and most poetic Amazon reviews, the sheer number of which helped him earn the rarefied “Top 100” and “Hall of Fame” status on the site.

Who it's for: Fans of Wayne Koestenbaum and Dodie Bellamy, who wrote introduction and afterword, respectively; people who actually leave Amazon reviews. —DF

Cher by Cher [NF]

What it is: The first in a two-volume memoir, telling the story of Cher's early life and ascendent career as only she can tell it.

Who it's for: Anyone looking to fill the My Name Is Barbra–sized hole in their heart, or looking for something to tide them over until the Liza memoir drops. —SMS

The City and Its Uncertain Walls by Haruki Murakami, tr. Philip Gabriel [F]

What it is: Murakami’s first novel in over six years returns to the high-walled city from his 1985 story "Hard-Boiled Wonderland and the End of the World" with one man's search for his lost love—and, simultaneously, an ode to libraries and literature itself.

Who it's for: Murakami fans who have long awaited his return to fiction. —DF

American Bulk by Emily Mester [NF]

What it's about: Reflecting on what it means to "live life to the fullest," Mester explores the cultural and personal impacts of America’s culture of overconsumption, from Costco hauls to hoarding to diet culture—oh my!

Who it's for: Lovers of sustainability; haters of excess; skeptics of the title essay of Becca Rothfeld's All Things Are Too Small. —DF

The Icon and the Idealist by Stephanie Gorton [NF]

What it is: A compelling look at the rivalry between Margaret Sanger, of Planned Parenthood fame, and Mary Ware Dennett, who each held radically different visions for the future of birth control.

Who it's for: Readers of Amy Sohn's The Man Who Hated Women and Katherine Turk's The Women of NOW; anyone interested in the history of reproductive rights. —SMS

December

Rental House by Weike Wang [F]

What it's about: Married college sweethearts invite their drastically different families on a Cape Code vacation, raising questions about marriage, intimacy, and kinship.

Who it's for: Fans of Wang's trademark wit and sly humor (see: Joan Is Okay and Chemistry); anyone with an in-law problem.

Woo Woo by Ella Baxter [F]

What it's about: A neurotic conceptual artist loses her shit in the months leading up to an exhibition that she hopes will be her big breakout, poking fun at the tropes of the "art monster" and the "woman of the verge" in one fell, stylish swoop.

Who it's for: Readers of Sheena Patel's I'm a Fan and Chris Kraus's I Love Dick; any woman who is grateful to but now also sort of begrudges Jenny Offil for introducing "art monster" into the lexicon (me). —SMS

Berlin Atomized by Julia Kornberg, tr. Jack Rockwell and Julia Kornberg [F]

What it's about: Spanning 2001 to 2034, three Jewish and downwardly mobile siblings come of age in various corners of the world against the backdrop of global crisis.

Who it's for: Fans of Catherine Lacey's Biography of X and Joshua Cohen's The Netanyahus. —SMS

Sand-Catcher by Omar Khalifah, tr. Barbara Romaine [F]

What it is: A suspenseful, dark satire of memory and nation, in which four young Palestinian journalists at a Jordanian newspaper are assigned to interview an elderly witness to the Nakba, the violent 1948 expulsion of native Palestinians from Israel—but to their surprise, the survivor doesn’t want to rehash his trauma for the media.

Who it’s for: Anyone looking insight—tinged with grim humor—into the years leading up to the present political crisis in the Middle East and the decades-long goal of Palestinian autonomy. —NodB

The Shutouts by Gabrielle Korn [F]

What it's about: In the dystopian future, mysteriously connected women fight to survive on the margins of society amid worsening climate collapse.

Who it's for: Fans of Korn's Yours for the Taking, which takes place in the same universe; readers of Becky Chambers and queer-inflected sci-fi. —SMS

What in Me Is Dark by Orlando Reade [NF]

What it's about: The enduring, evolving influence of Milton's Paradise Lost on political history—and particularly on the work of 12 revolutionary readers, including Malcom X and Hannah Arendt.

Who it's for: English majors and fans of Ryan Ruby and Sarah Bakewell—but I repeat myself. —SMS

The Afterlife Is Letting Go by Brandon Shimoda [NF]

What it's about: Shimoda researches the mass incarceration of Japanese Americans during WWII, and speaks with descendants of those imprisoned, for this essay collection about the “afterlife” of cruelty and xenophobia in the U.S.

Who it’s for: Anyone to ever visit a monument, museum, or designated site of hallowed ground where traumatic events have taken place. —NodB

No Place to Bury the Dead by Karina Sainz Borgo, tr. Elizabeth Bryer [F]

What it's about: When Angustias Romero loses both her children while fleeing a mysterious disease in her unnamed Latin American country, she finds herself in a surreal, purgatorial borderland where she's soon caught in a power struggle.

Who it's for: Fans of Maríana Enriquez and Mohsin Hamid. —SMS

The Rest Is Silence by Augusto Monterroso, tr. Aaron Kerner [F]

What it is: The author of some of the shortest, and tightest, stories in Latin American literature goes long with a metafictional skewering of literary criticism in his only novel.

Who it's for: Anyone who prefers the term "palm-of-the-hand stories" to "flash fiction." —JHM

Tali Girls by Siamak Herawi, tr. Sara Khalili [F]

What it is: An intimate, harrowing, and vital look at the lives of girls and women in an Afghan mountain village under Taliban rule, based on true stories.

Who it's for: Readers of Nadia Hashimi, Akwaeke Emezi, and Maria Stepanova. —SMS

Sun City by Tove Jansson, tr. Thomas Teal [F]

What it's about: During her travels through the U.S. in the 1970s, Jansson became interested in the retirement home as a peculiarly American institution—here, she imagines the tightly knit community within one of them.

Who it's for: Fans of Jansson's other fiction for adults, much of which explores the lives of elderly folks; anyone who watched that documentary about The Villages in Florida. —SMS

Editor's note: We're always looking to make our seasonal book previews more useful to the readers, writers, and critics they're meant to serve. Got an idea for how we can improve our coverage? Tell me about it at sophia@themillions.com.

[millions_email]

A Year in Reading: The Book Report

Welcome to a very special episode of The Book Report presented by The Millions! In this episode, Janet and Mike get into the holiday spirit by discussing their literary regrets. Also, check out their Christmas trees!

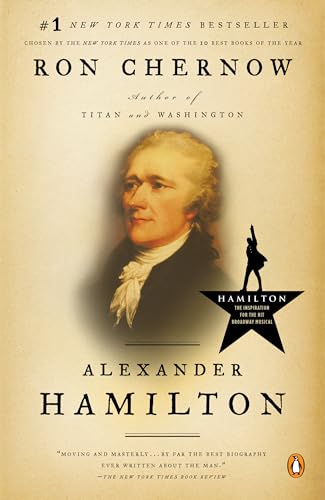

Discussed in this episode: "My Way" by Paul Anka, Festivus, Hamilton by Lin-Manuel Miranda, Alexander Hamilton by Ron Chernow, Far from the Madding Crowd by Thomas Hardy, The Scarlet Letter by Nathaniel Hawthorne, Dune by Frank Herbert (which still sucks), Dune (dir. David Lynch), unearned positive reviews, The Life-Changing Magic of Tidying Up: The Japanese Art of Decluttering and Organizing by Marie Kondo, book critic detectives, The Southern Reach Trilogy by Jeff VanderMeer, Elena Ferrante.

Cut for time from this episode: We riffed on Dune for a good 15 minutes.

More from A Year in Reading 2015

Don't miss: A Year in Reading 2014, 2013, 2012, 2011, 2010, 2009, 2008, 2007, 2006, 2005

The good stuff: The Millions' Notable articles

The motherlode: The Millions' Books and Reviews

Like what you see? Learn about 5 insanely easy ways to Support The Millions, and follow The Millions on Twitter, Facebook, Tumblr.

The Light of Suffering: Thomas Hardy in 21st-Century Florida

1.

During my first Christmas break as a high school English teacher in Florida, I sat down with the curriculum, a hand-written list of books Xeroxed so many times that the edges of the letters had become blurry. I had choices with the “Modern Novel,” the next unit of the year. The department head -- an ardent, tough teacher of three decades, who had parents protest her teaching of Marquez, who taught Their Eyes Were Watching God to freshmen — reminded me, “If you care for it, you can make the kids care about it.”

When I saw that Thomas Hardy’s The Mayor of Casterbridge was a “Modern Novel” on the senior year curriculum, I felt a great space open in my chest. I read Hardy’s poetry, Far From the Madding Crowd, and Tess of the D’Urbervilles in college. I didn’t know novels could so unflinching and unblinking. In Hardy, life doesn’t “work out” for everyone. Good people suffer and they die and the world does not ripple at their death. Survival, happiness even, demands compromise, eschewal, and tragedy.

Yes, I was making the choice to ask my students to read what I had. I allowed the kismet of the Hardy option to meet my impulse. His Wessex, the fictional Southwest England setting of his novels, had the same cycles of boom-bust Florida: nature razed for shaky industries, gray metal creeping across green fields. Men, always men, catching feelings about the money to be made, then deciding that the slow rituals of the past can be tossed away.

2.

The Mayor of Casterbridge's narrative is largely aftermath. In the first chapter, a 20-something hay trusser named Michael Henchard gets catastrophically drunk at a country fair and auctions off his young wife and infant daughter in a fit of self-pitying rage. Hardy’s narrator summarizes Henchard’s beta-male wallowing in the moments before the sale: “The conversation took a high turn...the ruin of good men by bad wives, and, more particularly, the frustration of many a promising youth’s high aims and hopes, and the extinction of his energies, by an early imprudent marriage.” Henchard awakes the next morning, takes a public pledge to abstain from liquor for 20 years, leaves the fair ground, and heads down the south coast of England to the regional hub of Casterbridge.

Almost 20 years later, Henchard has made himself into an agricultural plutocrat. But his white-hot rage and self-loathing burns on. He abuses his employees, fires them on a whim, and white-knuckles his sobriety. When we first see him in middle-age, he’s at the head of a table in Casterbridge’s upmarket inn, surrounded by subordinates, drinking “from his tumbler of water as if to calm himself or to gain time.”

The eyes through which we see this updated but unchanged vision of Henchard? A beautiful, naïve 20-something girl new to town: Henchard’s long-lost daughter, Elizabeth-Jane. The plot unfurls from there in a way that only serialized novels of the Victorian era can. Ancillary characters relay information under the drooping eaves of a shack, the narrator lingers on the symbolism of a bridge’s materials (Hardy himself was trained as an architect), lovers appear suddenly and die accidently, and a bright and decent young Scotsman named Farfrae with new devices for increasing grain production and eyes for Elizabeth-Jane becomes Henchard’s protégé.

In that first year, before asking the students to write a critical essay on the novel, I asked the seniors to “reboot” The Mayor of Casterbridge by writing five-page treatments set in 21-century south Florida.

The results astonished me. Students transformed the grain industry to the hotel business, peopled their stories with car salesmen, and even managed to work in the cocaine trade (thanks, lax bros!). The tumult of Hardy’s take on family and paternity became multi-ethnic families, hidden religious conversions, and addictions to pills or gambling. A right-wing Cuban patriarch (a Henchard) sells his wife and daughter not out of a corn-whiskey abyss but out of a shame for his Caribbean wife and child’s blackness. The end of the agrarian way of life in Hardy’s eyes became, in the eyes of a young woman whose family works on the boats and yachts in Palm Beach County, the transformation of a sleepy, humble fishing village into a glossy, anonymous eco-resort by a young, well-intentioned real estate developer (a Farfrae).

I had read their college essays in the fall. Adolescents, no matter how savvy or guarded, cannot help but disclose. Many of their Hardy-founded creative writings overlapped with their personal essays. Things that they had written in the fall, episodes from their young lives, came back again in their fiction: addiction, the working class, parents, how we live in the natural world, their stories in their towns in Florida, the unforgivable acts that only those close to you can commit, the things about yourself that you will never be able to change. They had shown me, in those college essays, glimpses of themselves at their most vulnerable.

My students conjured Floridian visions of Casterbridge that reflected the state. What would happen when the economy went cadaverous again and the boats and hotel guests disappeared, and Governor Rick Scott decided that fracking the Everglades was the future? How will my students react when the state tries to drug test SNAP recipients? What about when a private prison company tries to sponsor FAU’s football stadium? What about when another black child is killed by the police? To live in Florida in 2015 is to distrust beauty, to suspect relief.

The alchemy of book, classroom setting, geography, cultural moment, and motivated students had produced the godhead of the English classroom: Authentic connections across time, space, and between individual and group. Students were learning that literature’s “equipment for living,” to borrow Kenneth Burke’s phrase, could live inside a 19th-century novel, and that this equipment was honed by suffering resembling their own.

I wondered if I had done anything particularly special. Yes, I love Hardy. Yes, the book came late enough in the term for students to deploy their training in close reading and in claim making. Yes, I did well in setting up the novel, showing slides from the Lake District before showing an image of Picasso’s "Guernica" and asking the students to think about Hardy as the bridge between eras of thinking, ages of belief.

What I could never say, what a teacher should never say, is that I saw myself in one the characters: Michael Henchard. I drank fiercely in my 20s. I alienated peers; lost weekends; spoilt relationships with potential mentors; twisted quiet gatherings into loud, repulsive stand-up; said needlessly provocative things. I did not apologize. Living with shame felt like enough. When I read Henchard’s dialogue to the class, I felt the desperation. I felt how each stupid, instinctual decision he makes in the novel is an attempt to claw back the past, to scrub the quintessential, unnamable weaknesses out of his soul. When I made cases to my students for why Henchard could not be written off as “the worst” or “evil,” I rooted around for how I might defend the worst corners of myself. Sure, I played devil’s advocate for Henchard to present the pithy idea of “human frailty.” But I also played that part to uncover, label, and put away a version of myself.

Did I speak with particular power on Henchard? Did my voice rise in urgency? Did I offer the students a glimpse of the unexpected -- digging for identification in a destructive character? What other doors had Casterbridge propped open? Was Henchard a glimpse of their mother? Their brother struggling with pills outside Tampa? How many Elizabeth-Janes did I have in my classroom? Had I made enough space for her story and the stories of my students who saw themselves in her?

3.

In my second year teaching Casterbridge, I omitted the creative assignment. Instead, I asked the students to write an in-class essay about a symbol from the final chapters. Hardy wrote two endings for the novel, and I hesitate to spoil either of them. Both devastate. I foregrounded Casterbridge on our final exam, making the students juxtapose Henchard against other protagonists we read that year: Beowulf, Macbeth, and others. This time the student work was more clinical. Instead of mining their own lives, they examined, like astute literary surgeons, how exactly Henchard’s weaknesses and Elizabeth-Jane’s resilience circle each other in ways that recall Macbeth’s weaknesses and Banquo’s stoicism. One student -- an international student, far from home, writing in her second language -- wrote a brilliant in-class essay on how Henchard and Macbeth destroy their social and familial networks because their shared “unchecked” ambition confuses destruction with the desire to change. Her essay’s title: “Defeated By Life.”

I’ve just re-read her essay for at least the fifth time, and I wonder about what happened among Hardy, my students, Florida, 2015, and me. If the teenage years are hard enough, what business did I have adding to the misery? In Philip Larkin’s essay on Hardy, “Wanted: A Good Hardy Critic,” he makes the case that Hardy’s chief subject is “suffering.” Larkin argues that inaccurate readers see Hardy’s central characters as a “galleries of ‘losers’ against whom is ranged a contrasting gallery of winners.” We should instead, Larkin writes, see that suffering is “both the truest and the most important element in life, most important in the sense of most necessary to spiritual development.”

Moments of our Florida seemed comfortable: the blistering, pre-lapsarian beauty of seeing parchment-white ibises strolling between the school buildings and hearing students yelling happily as they run out of the school, the daily afternoon rain pausing overhead.

But high school English teachers know two things: adolescence is hard, and the literature you teach should reflect your students’ lives. Therefore, teenagers deserve literature that supplies suffering. For the students living through suffering, Hardy, and writers like him, can locate a student’s suffering and reflect it. That reflection can be a step toward recovery and development. The students living a life of comfort require the shaking alarm bell that survival is hard, people are deeply fallible, and life comprehensively unfair.

You, the teacher, have to dive into yourself to find the books that touch upon your suffering. You’ll teach them with greater urgency and match them to the sufferings of your students. They’ll engage with them -- critically, imaginatively -- with greater desire. In 2015, text complexity -- the degree to which a book challenges, to the point of productive discomfort, a student with its vocabulary, syntax, rhetoric, and structure -- is coin of the realm of the English classroom. Take that a step further. At the highest level, the deepest mode of text complexity should foster the deepest kinds of emotional engagements from the teacher and the students. If the book doesn’t affect and afflict everyone in the room, what’s the point? The prevailing winds of education theory seem to advocate for the opaque, “guide on the side” teacher who makes her or his stakes in the text mysterious at best.

Oddly enough, this desire reminds me of Henchard’s final act in Casterbridge: his writing of a will that demands that he be forgotten, that “no sexton be asked to toll the bell. & that nobody is wished to see my dead body. & that no murners walk behind me at my funeral. & that no flours be planted on my grave. & that no man remember me.”

But life, like the classroom, doesn’t work that way. Here, among teenagers and rough drafts, there is no place where the story cannot not see us. We, the students and the teacher, have to stand together under the discomforting light of what we might call suffering, what we might call literature.

Image Credit: Wikipedia.

The Book Report: Episode 19: ‘Far From the Madding Crowd’

Welcome to The Book Report presented by The Millions! This week, The Book Report goes to the movies, and Janet and Mike discuss the film that's dominating the box office this summer: Mad Max: Beyond the Madding Crowd.

Discussed in this episode: Far from the Madding Crowd by Thomas Hardy, Far from the Madding Crowd (dir. Thomas Vinterberg), mozzarella sticks, movie tie-in editions, melodrama, guys who are good in their faces, old drunks, The Bachelorette, Matthias Schoenaerts, and hot damn Michael Sheen is a great actor and seemingly a lady-killer...

Trailers watched in the movie theater before Far from the Madding Crowd started: We can only remember one and it was for that movie about Brian Wilson and he is played by both Paul Dano and John Cusack because why not, I guess.

February Books: A Reading List for Love and Late-Winter Gloom

"It is February," Anne Carson once wrote, perhaps from within the polar vortex. "Ice is general." By the time we get to February, the days may be getting longer, but there is a weariness to the winter. Hibernation's novelty has long expired, and the fruits of the fall harvest are running low. On the coldest day of 1855, Henry David Thoreau noted the old saying that "by the 1st of February the meal and grain for a horse are half out." (He spent the rest of that frozen month skating on the local rivers.)

But in the middle of the month the calendar calls to break the ice with romance. We've settled on February 14, the feast day of St. Valentine, as love's holiday, but there's little evidence that any of history's St. Valentines were linked to romance until Geoffrey Chaucer, first artificer of so much in our language, joined them in his Parliament of Fowls: "on Seynt Valentynes day, / Whan every foul cometh there to chese his make." (And even he may have had an Italian St. Valentine's festival in May, not February, in mind.) We celebrate birthdays too in February: Lincoln's, for instance, a holiday Richard Wright chose for his first novel, Cesspool (published after his death as Lawd Today), a violent and raunchy satire of one day in the lives of a Chicago postal worker and his friends. And some authors have celebrated their own February birthdays: James Joyce asked that Ulysses be published on the day he turned forty, February 2, 1922, while Toni Morrison, one of the least autobiographical of novelists, nevertheless tucked a small hint of herself into the first page of Song of Solomon: the day the insurance agent Robert Smith announces he will fly from the cupola of Mercy Hospital is February 18, 1931, the date of Morrison's own birth in Lorain, Ohio.

Here is a selection of recommended reading for February, full of love, birthdays, and late-winter gloom:

Persuasion by Jane Austen (1818)

Austen readers looking for a love story in the month of valentines have many choices, but her last novel, the story of an overlooked but independent woman finding love despite obstacles of her own creation, offers perhaps the most moving moment in all her work: the unexpected delivery of a love letter upon which all depends.

Domestic Manners of the Americans by Frances Trollope (1832)

Mrs. Trollope's February arrival in the frontier town of Cincinnati (she left her future-novelist son at home in England) may have led to business disaster -- the glamorous department store she struggled to build there failed -- but ultimately it made her fortune, thanks to this sharp-tongued and coolly observant travelogue, a scandal in America but also a bestseller.

Far from the Madding Crowd by Thomas Hardy (1874)

There are plenty of obstacles between Bathsheba Everdene and true love in Hardy’s breakthrough novel, beginning with an idle and frolicsome Valentine’s Day joke that turns deadly serious. This being Hardy, more death follows.

Life and Times of Frederick Douglass by Frederick Douglass (1881; 1892)

The third autobiography of Douglass, who chose to celebrate his unrecorded birthday on Valentine’s Day, doesn’t carry the compact power of his original 1845 slave narrative, but it’s a fascinating and ambivalent self-portrait of a half-century in the public life that was launched by that bestselling Narrative.

Charlie and the Chocolate Factory by Roald Dahl (1964)

Every day is more or less the same at the Buckets’ tiny ramshackle house—watery cabbage soup for dinner and the winter wind whistling through the cracks—until young Charlie Bucket finds a dollar in the snow and then a Golden Ticket in his chocolate bar inviting him to appear at the Wonka factory gate on February 1 at 10 o'clock sharp.

The Left Hand of Darkness by Ursula K. LeGuin (1969)

One of the most challenging and imaginative of love stories takes place entirely in winter, as an envoy from Earth has to learn to negotiate an ice-bound planet populated by an androgynous people who can take the role of either sex during their monthly heat.

Moortown Diary by Ted Hughes (1979)

These poems from the decade Hughes and his third wife took to farming in North Devon, the country of her birth, are journal entries hewn rough into verse, wet and wintry like the country and full of the blood and being of animals.

The Breaks of the Game by David Halberstam (1981)

February is doldrums season in the National Basketball Association, well into the slog of the schedule but still far from the urgency of the playoffs, and few have captured the everyday human business of the itinerant professional athlete better than Halberstam in his portrait of the ’79-’80 Trailblazers’ otherwise forgettable season.

Ravens in Winter by Bernd Heinrich (1989)

Over four Maine winters, with as much ingenuity and persistence as his intelligent subjects and an infectious excitement for the drama of the natural world — the “greatest show on earth” — Bernd Heinrich tried to solve the mystery of cooperation among these solitary birds, better known as literary symbols than as objects of study.

Julius Knipl, Real Estate Photographer by Ben Katchor (1996)

"By the second week in February, the city's wholesale calendar salesmen pack up their samples and enter a state of self-induced hibernation," begins one of the comic-strip tales in Katchor's second Knipl collection, which celebrates the minor industries, fading establishments, and idle off-seasons of his unnamed city with a profound, if paunchy, elegance.

February House by Sherrill Tippens (2005)

Fans of literary anecdotes and surprising artistic encounters will find an embarrassment of riches in this account of the short time in the early ’40s when Carson McCullers, W. H. Auden, Paul and Jane Bowles, stripper-turned-novelist Gypsy Rose Lee, and others shared a Brooklyn brownstone that got its nickname because so many among them (McCullers, Auden, Jane Bowles, and house organizer George Davis) had birthdays in this month.

Here is My Heart: The Frailty and Hope of William Saroyan

Love, Here is My Hat: I came across a copy of William Saroyan’s book in a Vermont used book store not long ago and clasped it, rather melodramatically, to my heart. The book itself has hearts on the cover -- two red ones floating above images of a man and a woman, and of a cupid and a bed sketched on a pink-ish background. I bought it, forgetting for the moment that I already own a copy of the exact same edition. Even if I had several copies, though, I would have needed to make the purchase that day because my heart needed tending.

I had driven to Vermont to visit a child in college, but most of all to clear my head. A storm threatened to stop me part way, and as I crept along the snow-covered roads, I fought the urge to see the journey as a parallel for that stage in my marriage. And yet, there it was: unseen hazards, poor traction, and a route at times so difficult that it threatened to turn both me and my husband back. I thought of what I could ask of my life, and how happy I could expect to be. It wasn’t a mawkish question, but a practical one: what did I want? I believed I needed answers, that I owed it to myself to ask. But the next day, there was Saroyan’s familiar book and it wasn’t asking a question at all. It was offering.

I have loved Saroyan’s short stories since I first encountered them among the yellowed Pocket and Avon Books of my father’s wartime collection. These were all-American paperbacks, their jacket copy exhorting the reader to support the GIs and their contents full of “See?” and “fella.” That they should end up in a closet in my grandmother’s house in Greece was a large part of their appeal. Inherently nostalgic, describing a period 30 years removed from my teenage life, the books became for me doubly so as they evoked a distant America while the weeks of my Greek summers wound down and the pull of home in New England grew stronger. Each summer, I would tug 48 Saroyan Stories gently from the shelf and flip the brittle pages as if they were rare manuscripts. I would imagine the book in my father’s back pocket as he walked the streets of an Athens newly liberated from German occupation. And I would be carried off to a California of orchards, diners, and flophouses, an America of trains and dirt roads and bellhops looking to make ends meet. In Saroyan’s writing, I encountered a United States that was both exotic and familiar.

Many years ago, I asked my father if I could bring the Saroyan home with me, and I think he was touched that I found such value in this particular souvenir. Together with some Erle Stanley Gardner noirs and Leslie Charteris’s Saint books, these were the stories that had taught my father English. But it was Saroyan in particular who taught him the language of America, the adopted country that he deeply loved, and that he returned to with pride after his own Greek sojourns.

48 Saroyan Stories now sits in a glass-fronted cabinet, separated from the rest of the fiction arranged alphabetically in another room. Over the years I’ve added more Saroyan finds to the cabinet: Love, Here is My Hat; Peace, It’s Wonderful; The Human Comedy; and My Name Is Aram. These volumes sit alongside an early edition of Far From the Madding Crowd and some first editions of W.B. Yeats. The Hardy is leather, softened with the handling of almost two hundred years. The Yeats collections are beautiful hardcovers decorated in classic 1920s style. With their rubbed-round corners and torn spines, the Saroyans are like the interloping distant relatives at the wedding who laugh too loud and don’t know how to dress.

When I saw Love, Here is My Hat in Vermont that day, I needed to buy it again because Saroyan appeals to my heart and not my literary head. I bought it because Saroyan signals the pull of something or someplace absent; because the stories collected there are about people trying to make do, to make simple lives of love and happiness; and most of all because the book and that title I’ve never quite understood represent an offer. Here is my hat. Perhaps it’s a gesture of surrender, or of begging. I’m not really sure, and I’ve resisted researching the phrase to find out what it might have meant in 1938. It doesn’t matter. The book offers a gift of some kind. Here, the writer says. Take this.

It’s important to me that it’s Saroyan himself who seems to be making the gesture. In the title story, which also appears in my father’s old paperback, no one utters the phrase. Nor does anyone in any other story in the book. “Love, Here is My Hat” tells the story of a man and a woman who are so plagued by love for each other that they cannot eat when they’re together. “I can’t live without you,” she says.

Yes, you can, I said. What you can’t live without is roast beef.

I don’t care if I never eat again, she said.

Look, I said. You’ve got to get some food and sleep, and so do I.

I won’t let you go, she said.

All right, I said. Then we’ll die of starvation together. It’s all right with me if it’s all right with you.

He goes away to Reno so they can both choke something down. But she finds out where he is and follows him there. She calls him on the phone.

Are you all right?

I want to cry, she said.

I’ll come and get you, I said.

Did you eat? she said.

Yes, I said. Did you?

No, she said. I couldn’t.

Before my husband and I were married, the rhythms of graduate school kept us apart for two months at a time. As the date of my departure for England approached each cycle, we found it harder and harder to eat. I told him about the story, and though it wasn’t a perfect match, it became, even a little bit for him, a kind of shorthand for how we felt. “Did you eat?” I would sometimes ask over the phone later, and I would think of the stark back-and-forth of Saroyan’s prose, and the barebones matters of love and separation that made his stories and that made up our world.

I bought the second copy of Love, Here is My Hat not really thinking about the title. It was only as I gave the book to my husband, 30 years after our cycles of separation and return, that I realized how I’d been misreading it. Here is my heart. I held the book out with both hands as if it were truly precious, and it hit me. To me, Saroyan’s book and all his stories are imbued with frailty and hope, with the tentative gestures of people who don’t have or expect much, but still offer what they consider basic: their hearts. Love, Here is My Hat. Or my heart. Either way, the phrase suggests an offer with no certainty of acceptance. Like a hat held out, it’s an offer that risks disappointment but still hopes for something in return. We make the gesture all the same -- even when we think we should know better.

My husband took the book from me that day and held it just as gently as I had. He listened to what I had to say -- about my father and about the lovers who cannot eat and about my heart -- and understood. Now there are two copies of Saroyan’s book in the house. Mine sits on my desk beside my laptop, and his copy rests on his nightstand. Not reading matter, it’s more of a reminder, perhaps to both of us, of how important it is to offer without knowing what the outcome will be.

In that vulnerability lies the beauty of Saroyan’s work. It is simple. It is basic. It doesn’t lay claim to any grander place in literature, nor does it deserve one. It is, sometimes, all we need. A little book, an offer, a question. Did you eat?

Image Credit: Wikipedia

The Elusive Omniscient

As I was taking notes for a new novel recently, I took a moment to consider point of view. Fatigued from working on one manuscript with multiple first-person limited narrators, and then another with two different narrative elements, I thought how simple it would be, how straightforward, to write this next book with an omniscient point of view. I would write a narrator who had no constraints on knowledge, location, tone, even personality. A narrator who could do anything at any time anywhere. It wasn’t long before I realized I had no idea how to achieve this.

I looked for omniscience among recent books I had admired and enjoyed. No luck. I found three-handers, like The Help. I found crowd-told narratives, like Colum McCann’s elegant Let The Great World Spin. I found what we might call cocktail-party novels, in which the narrator hovers over one character’s shoulder and then another’s, never alighting for too long before moving on.

On the top layer of my nightstand alone, I found Lionel Shriver’s The Post-Birthday World and Jane Gardam’s Old Filth and The Man in the Wooden Hat. The first is a formal experiment in which alternating narratives tell the same story of a marriage—which is really two different stories, their course determined by just one action. The second two give up on shared perspective altogether, splitting the story into separate books. Old Filth tells his story and The Man in the Wooden Hat tells hers. If the contemporary novel had a philosophy, it would be Let’s Agree To Disagree.

It’s tempting to view this current polyphonic narrative spree as a reflection on our times. Ours is a diverse world, authority is fragmented and shared, communication is spread out among discourses. Given these circumstances, omniscience would seem to be not only impossible but also undesirable—about as appropriate for our culture as carrier pigeons. It’s also tempting to assume that if we’re looking for narrative unity, we have to go back before Modernism. We can tell ourselves it was all fine before Stephen Dedalus and his moo-cow, or before Windham Lewis came along to Blast it all up.

No, if omniscience was what I wanted for my next project, I would have to look back further, to a time when the novel hadn’t succumbed to the fragmentation of the modern world.

But try it. Go back to the Victorians or further back to Sterne, Richardson, and Fielding. There’s no omniscience to be found. I suppose I could have spared myself the trouble of a search by looking at James Woods’ How Fiction Works. “So-called omniscience,” he says, “is almost impossible.” It turns out that the narrative unity we’ve been looking for is actually a figment of our imagination. The novel maintains an uneasy relationship with authority—not just now, but from its very beginnings.

Defoe’s Robinson Crusoe is often credited with being the first novel in the English language, published in 1719. The anxieties attendant on that role are evident in the way the book is structured. Not comfortable claiming to be simply an invention, Crusoe masquerades as a true story, complete with an editor’s preface declaring the book to be “a just history of fact; neither is there any appearance of fiction in it.” Defoe originates the James Frey approach to novel-writing, using the pretense of truth as a source of narrative power.

He repeats almost the same phrasing four years later, in Roxana: “The foundation of this is laid in truth of fact, and so the work is not a story, but a history.” The words seem redundant now—truth, fact, foundation, history. It’s a protesting-too-much that speaks to the unsettled nature of what Defoe was doing: telling a made-up story of such length, scope, and maturity at a time when doing so was still a radical enterprise.

But the most interesting expression of the novel’s predicament comes one year before Roxana, in 1722, when Defoe opens Moll Flanders with an excuse: “The world is so taken up of late with novels and romances that it will be hard for a private history to be taken for genuine.” It’s a clever move. Defoe acknowledges the existence of enough novels that you’d think his position as novelist would be secure (the more the merrier), but he insists that he’s doing something different—and then in the same breath assumes our lack of interest and then preempts it by setting up the other novels as tough competition.

Defoe’s pretense of editors, prefaces, and memorandums is the first stage of what I’ll call the apparatus novel, followed a decade or two later by its close cousin, the epistolary novel. Like its predecessor, the epistolary novel can’t just come out and tell a made-up story—never mind tell one from an all-knowing point of view. In Richardson’s Clarissa especially, the limitations of the individual letter-writers’ points of view create an atmosphere of disturbing isolation. As we read through Clarissa’s and Lovelace’s conflicting accounts, we become the closest thing to an omniscient presence the novel has—except we can’t trust a word of what we’ve read.

So where is today’s omniscience-seeking reader to turn? Dickens, don’t fail me now? It turns out that the Inimitable Boz is no more trustworthy in his narration than Defoe or Richardson or the paragon of manipulative narrators, Tristram Shandy. In fact, Dickens’ narrators jump around all over the place, one minute surveying London from on high, the next deep inside the mind of Little Dorrit, or Nancy, or a jar of jam. Dickens seems to have recognized the paradox of the omniscient point of view: with the ability to be everywhere and know everything comes tremendous limitation. If you’re going to let the furniture do the thinking, you’re going to need the versatility of a mobile and often fragmented narrative stance.

And Dickens is not alone in the 19th century. The Brontës? Practically case studies for first-person narration. Hardy? Maybe, but he hews pretty closely to one protagonist at a time. (Though we do see what’s happening when Gabriel Oak is asleep in Far From the Madding Crowd.) Dickens good friend Wilkie Collins (who famously said the essence of a good book was to “make ‘em laugh, make ‘em cry, make ‘em wait”)? The Moonstone is a perfect example of the apparatus novel, anticipating books like David Mitchell’s Cloud Atlas, complete with multiple narrators, various types of discourse, and full of statements that successive narrators correct or undermine.

This isn’t to say that there are no omniscient novels anywhere. Look at Eliot or Tolstoy, to jump cultures, or Austen. Sure, the line on Austen is that she could only write about drawing-room life, but she still writes books in which the narrator knows everything that’s going on in the novel’s world. Pride and Prejudice begins with its famous statement about men, money, and wives, and then easily inhabits the minds of various members of the Bennett family and their acquaintances—not through first-person limited, but through the more detached and stance of a true omniscient narration. Doubtless, readers could come up with other works written from an all-knowing perspective. Friends have suggested books as different as The Grapes of Wrath and One Hundred Years of Solitude as omni-contenders.

All the same, what seems key about the novel is that what we think of as a historical evolution—or a descent from a unified to a fragmented perspective—isn’t an evolution at all. In fact, the novel has always been insecure. It’s just that the manifestation of its insecurity has changed over time. At the outset, it tried to look like a different sort of artifact, a different kind of physical manuscript almost: the novel masked as a diary or a journal—because, really, who knew what a novel was anyway? Later, seeking to convey more intimate thoughts, it took the form of letters, acting like a novel while pretending to be something else, just in case. This is a genre that constantly hedges against disapproval. It’s like a teenager trying not to look like she’s trying hard to be cool. (Novel, who me? Nah, I’m just a collection of letters. I can’t claim any special insight. Unless you find some, in which case, great.)

Omniscience is something that the novel always aspires for but never quite achieves. It would be nice to have the authority of the all-seeing, all-knowing narrator. But we are too tempted by other things, like personality, or form, or the parallax view that is inherent to our existence. This is why, I think, when you ask readers to name an omniscient novel, they name books that they think are omniscient but turn out not to be. Wishful thinking. The omniscient novel is more or less a utopia, using the literal meaning of the word: nowhere.

Appropriately, Thomas More structured Utopia as a kind of fiction, an apparatus novel about a paradise whose exact location he had missed hearing when someone coughed. This was in 1516, two full centuries before Robinson Crusoe, making Utopia a better candidate for First English Novel. But that’s a subject for another day.

[Image credit: Tim]

Geometric Solids: Thomas Hardy’s Far From the Madding Crowd

I first heard about Thomas Hardy's Far From the Madding Crowd about twenty years ago, when I was in seventh or eighth grade. My classmates and I were all reading Stephen King and Dean R. Koontz, and our English teacher attempted to guide our reading choices to higher-brow material."I think it's great that you're all reading so much," she said. "But when you're choosing books to read, try to read classics." She mentioned, for example, that she had recently read Far From the Madding Crowd while recovering from surgery.I had no intention of abandoning King or Koontz, but I did check out a copy of Hardy's novel from the public library. I tried to read it but didn't get far. The first two paragraphs had enough unfamiliar vocabulary and tonal foreignness to repel me as a thirteen-year-old:When Farmer Oak smiled, the corners of his mouth spread till they were within an unimportant distance of his ears, his eyes were reduced to chinks, and diverging wrinkles appeared round them, extending upon his countenance like the rays in a rudimentary sketch of the rising sun.His Christian name was Gabriel, and on working days he was a young man of sound judgment, easy motions, proper dress, and general good character. On Sundays he was a man of misty views, rather given to postponing, and hampered by his best clothes and umbrella: upon the whole, one who felt himself to occupy morally that vast middle space of Laodicean neutrality which lay between the Communion people and the drunken section.It took me ten years to try another Hardy novel, Tess of the D'Urbervilles, which I read and loved after my first year as an English teacher myself. The pleasures afforded by Hardy's fiction, I realized, require patience, a more mature appreciation of language, wider knowledge of the adult world, and a sense of the past. (Google is helpful, too, in deciphering Hardy's obscure mythological and Biblical references.)This summer, as I picked up Far From the Madding Crowd for another go, I was better equipped to appreciate Hardy's wryly delicate humor in passages like the following: "It may have been observed that there is no regular path for getting out of love as there is for getting in. Some people look upon marriage as a short cut that way, but it has been known to fail."Funny - and, indeed, as in Tess and The Return of the Native, in this novel Hardy concerns himself with love's entanglements. Bathsheba Everdene, a young and imperious beauty, named for the woman who occasioned King David's sinful plotting, finds herself involved not in a romantic triangle, but a romantic quadrilateral, as three men vie for her affections. Their names, like hers, are evocative of their identities: Oak, the solid shepherd; Boldwood, the increasingly audacious farmer; and the Troy, the scoundrel as fallen as the citadel that is his namesake.There's a reason that the romantic triangle is such a commonly-used fictional device: it has a geometric elegance, a pointedness that keeps a story moving. The romantic quadrilateral is harder to make work. Hardy does it well enough that 135 years later people are still reading the book. Compared to later works like Tess and Native, though, this one - the earliest of Hardy's best - known novels - is a bit of a disappointment.For one thing, it lacks a narrative center. This romantic quadrilateral is nothing so neat as a square or a rectangle. It's more ungainly - an irregular trapezoid, perhaps. It's difficult work to set up three suitors in a reasonably rounded way, and while Hardy's developing one, the other two tend to fade to the background. In the end, the male characters come perilously close to being as wooden as their names or, in Troy's case, a bit too starkly villainous.At times the plot's contrivances seem arbitrary, meant to force the narrative (originally published serially in a magazine) in its intended direction without especial regard for plausibility: Oak lies down in an apparently abandoned wagon, whose owners return and just so happen to be heading to Bathsheba's farm; Troy nearly drowns and, believed dead, runs off to America to join the circus for a convenient span of time, returning just when his presence will cause the most upheaval.Bathsheba herself, vain, proud, described by one of the men who marries her as "this haughty goddess, dashing piece of womanhood, Juno-wife of mine," seems to be a rough draft for Eustacia Vye, the more famous heroine of Hardy's Return of the Native. Eustacia (a favorite of Holden Caulfield's, you may recall) is, in Hardy's description, "the raw material of a divinity. On Olympus she would have done well," he writes, for "she had the passions and instincts which make a model goddess, that is, those which make not quite a model woman." In comparison to Eustacia, Bathsheba is too kind, too mortal, and less vivid.In other ways, too, Madding seems a rough draft of Native, which arranges its characters not in a triangle or quadrilateral, but in overlapping Venn diagrams of desire. In both novels, some characters come to tragic ends, some are seared by their experiences but survive, chastened but wiser. Return of the Native was published in 1878, four years after Far From the Madding Crowd, and in most ways it's a better book. It has a sharper sense of place; a more forceful narrative arc; more emotionally weighty and realistic plot turns; and, despite a rather tedious beginning in which backstory is provided by the gossip of eccentric country folk, less of such stock characters, whose humorousness has not aged well.I guess you could say that my eighth grade teacher gave me a bad recommendation. After all these years, finally reading this novel was a bit anticlimactic. But in the larger sense, she was right: King and Koontz may have been fine for my adolescence, but ultimately they were bridges to more ambitious reading projects. My teacher's offhanded remark about Hardy stuck with me, giving me a sense of the rewarding places to which those bridges might lead. Though I might have skipped this particular novel without much of a loss, Hardy's best work is definitely worth the journey.