Mentioned in:

A Year in Reading: 2024

Welcome to the 20th (!) installment of The Millions' annual Year in Reading series, which gathers together some of today's most exciting writers and thinkers to share the books that shaped their year. YIR is not a collection of yearend best-of lists; think of it, perhaps, as an assemblage of annotated bibliographies. We've invited contributors to reflect on the books they read this year—an intentionally vague prompt—and encouraged them to approach the assignment however they choose.

In writing about our reading lives, as YIR contributors are asked to do, we inevitably write about our personal lives, our inner lives. This year, a number of contributors read their way through profound grief and serious illness, through new parenthood and cross-country moves. Some found escape in frothy romances, mooring in works of theology, comfort in ancient epic poetry. More than one turned to the wisdom of Ursula K. Le Guin. Many describe a book finding them just when they needed it.

Interpretations of the assignment were wonderfully varied. One contributor, a music critic, considered the musical analogs to the books she read, while another mapped her reads from this year onto constellations. Most people's reading was guided purely by pleasure, or else a desire to better understand events unfolding in their lives or larger the world. Yet others centered their reading around a certain sense of duty: this year one contributor committed to finishing the six Philip Roth novels he had yet to read, an undertaking that he likens to “eating a six-pack of paper towels.” (Lucky for us, he included in his essay his final ranking of Roth's oeuvre.)

The books that populate these essays range widely, though the most commonly noted title this year was Tony Tulathimutte’s story collection Rejection. The work of newly minted National Book Award winner Percival Everett, particularly his acclaimed novel James, was also widely read and written about. And as the genocide of Palestinians in Gaza enters its second year, many contributors sought out Isabella Hammad’s searing, clear-eyed essay Recognizing the Stranger.

Like so many endeavors in our chronically under-resourced literary community, Year in Reading is a labor of love. The Millions is a one-person editorial operation (with an invaluable assist from SEO maven Dani Fishman), and producing YIR—and witnessing the joy it brings contributors and readers alike—has been the highlight of my tenure as editor. I’m profoundly grateful for the generosity of this year’s contributors, whose names and entries will be revealed below over the next three weeks, concluding on Wednesday, December 18. Be sure to subscribe to The Millions’ free newsletter to get the week’s entries sent straight to your inbox each Friday.

—Sophia Stewart, editor

Becca Rothfeld, author of All Things Are Too Small

Carvell Wallace, author of Another Word for Love

Charlotte Shane, author of An Honest Woman

Brianna Di Monda, writer and editor

Nell Irvin Painter, author of I Just Keep Talking

Carrie Courogen, author of Miss May Does Not Exist

Ayşegül Savaş, author of The Anthropologists

Zachary Issenberg, writer

Tony Tulathimutte, author of Rejection

Ann Powers, author of Traveling: On the Path of Joni Mitchell

Lidia Yuknavitch, author of Reading the Waves

Nicholas Russell, writer and critic

Daniel Saldaña París, author of Planes Flying Over a Monster

Lili Anolik, author of Didion and Babitz

Deborah Ghim, editor

Emily Witt, author of Health and Safety

Nathan Thrall, author of A Day in the Life of Abed Salama

Lena Moses-Schmitt, author of True Mistakes

Jeremy Gordon, author of See Friendship

John Lee Clark, author of Touch the Future

Ellen Wayland-Smith, author of The Science of Last Things

Edwin Frank, publisher and author of Stranger Than Fiction

Sophia Stewart, editor of The Millions

A Year in Reading Archives: 2023, 2022, 2021, 2020, 2019, 2018, 2017, 2016, 2015, 2014, 2013, 2011, 2010, 2009, 2008, 2007, 2006, 2005

The Great Fall 2024 Book Preview

With the arrival of autumn comes a deluge of great books. Here you'll find a sampling of new and forthcoming titles that caught our eye here at The Millions, and that we think might catch yours, too. Some we’ve already perused in galley form; others we’re eager to devour based on their authors, plots, or subject matters. We hope your next fall read is among them.

—Sophia Stewart, editor

October

Season of the Swamp by Yuri Herrera, tr. Lisa Dillman [F]

What it is: An epic, speculative account of the 18 months that Benito Juárez spent in New Orleans in 1853-54, years before he became the first and only Indigenous president of Mexico.

Who it's for: Fans of speculative history; readers who appreciate the magic that swirls around any novel set in New Orleans. —Claire Kirch

The Black Utopians by Aaron Robertson [NF]

What it is: An exploration of Black Americans' pursuit and visions of utopia—both ideological and physical—that spans the Reconstruction era to the present day and combines history, memoir, and reportage.

Who it's for: Fans of Saidiya Hartman's Wayward Lives, Beautiful Experiments and Kristen R. Ghodsee's Everyday Utopia. —Sophia M. Stewart

The Third Realm by Karl Ove Knausgaard, tr. Martin Aitken [F]

What it is: The third installment in Knausgaard's Morning Star series, centered on the appearance of a mysterious new star in the skies above Norway.

Who it's for: Real Knausgaard heads only—The Wolves of Eternity and Morning Star are required reading for this one. —SMS

Brown Women Have Everything by Sayantani Dasgupta [NF]

What it is: Essays on the contradictions and complexities of life as an Indian woman in America, probing everything from hair to family to the joys of travel.

Who it's for: Readers of Durga Chew-Bose, Erika L. Sánchez, and Tajja Isen. —SMS

The Plot Against Native America by Bill Vaughn [F]

What it is: The first narrative history of Native American boarding schools— which aimed "civilize" Indigenous children by violently severing them from their culture— and their enduring, horrifying legacy.

Who it's for: Readers of Ned Blackhawk and Kathleen DuVal. —SMS

The Mighty Red by Louise Erdrich [F]

What it is: Erdrich's latest novel set in North Dakota's Red River Valley is a tale of the intertwined lives of ordinary people striving to survive and even thrive in their rural community, despite environmental upheavals, the 2008 financial crisis, and other obstacles.

Who it's for: Readers of cli-fi; fans of Linda LeGarde Grover and William Faulkner. —CK

The Position of Spoons by Deborah Levy [NF]

What it is: The second book from Levy in as many years, diverging from a recent streak of surrealist fiction with a collection of essays marked by exceptional observance and style.

Who it's for: Close lookers and the perennially curious. —John H. Maher

The Bog Wife by Kay Chronister [F]

What it's about: The Haddesley family has lived on the same West Virginia bog for centuries, making a supernatural bargain with the land—a generational blood sacrifice—in order to do so—until an uncovered secret changes everything.

Who it's for: Readers of Karen Russell and Jeff VanderMeer; anyone who has ever used the phrase "girl moss." —SMS

The Great When by Alan Moore [F]

What it's about: When an 18-year old book reseller comes across a copy of a book that shouldn’t exist, it threatens to upend not just an already post-war-torn London, but reality as we know it.

Who it's for: Anyone looking for a Sherlock Holmes-style mystery dipped in thaumaturgical psychedelia. —Daniella Fishman

The Message by Ta-Nehisi Coates [NF]

What it's about: One of our sharpest critical thinkers on social justice returns to nonfiction, nearly a decade after Between the World and Me, visiting Dakar, to contemplate enslavement and the Middle Passage; Columbia, S.C., as a backdrop for his thoughts on Jim Crow and book bans; and the Israeli-occupied West Bank, where he sees contemporary segregation in the treatment of Palestinians.

Who it’s for: Fans of James Baldwin, George Orwell, and Angela Y. Davis; readers of Nikole Hannah-Jones’s The 1619 Project and Isabel Wilkerson’s Caste, to name just a few engagements with national and racial identity. —Nathalie op de Beeck

Abortion by Jessica Valenti [NF]

What it is: Columnist and memoirist Valenti, who tracks pro-choice advocacy and attacks on the right to choose in her Substack, channels feminist rage into a guide for freedom of choice advocacy.

Who it’s for: Readers of Robin Marty’s The New Handbook for a Post-Roe America, #ShoutYourAbortion proponents, and followers of Jennifer Baumgartner’s [I Had an Abortion] project. —NodB

Gifted by Suzuki Suzumi, tr. Allison Markin Powell [F]

What it's about: A young sex worker in Tokyo's red-light district muses on her life and recounts her abusive mother's final days, in what is Suzuki's first novel to be translated into English.

Who it's for: Readers of Susan Boyt and Mieko Kanai; fans of moody, introspective fiction; anyone with a fraught relationship to their mother. —SMS

Childish Literature by Alejandro Zambra, tr. Megan McDowell [F]

What it is: A wide-ranging collection of stories, essays, and poems that explore childhood, fatherhood, and family.

Who it's for: Fans of dad lit (see: Lucas Mann's Attachments, Keith Gessen's Raising Raffi, Karl Ove Knausgaard's seasons quartet, et al). —SMS

Books Are Made Out of Books ed. Michael Lynn Crews [NF]

What it is: A mining of the archives of the late Cormac McCarthy with a focus on the famously tight-lipped author's literary influences.

Who it's for: Anyone whose commonplace book contains the words "arquebus," "cordillera," or "vinegaroon." —JHM

Slaveroad by John Edgar Wideman [F]

What it is: A blend of memoir, fiction, and history that charts the "slaveroad" that runs through American history, spanning the Atlantic slave trade to the criminal justice system, from the celebrated author of Brothers and Keepers.

Who it's for: Fans of Clint Smith and Ta-Nehisi Coates. —SMS

Linguaphile by Julie Sedivy [NF]

What it's about: Linguist Sedivy reflects on a life spent loving language—its beauty, its mystery, and the essential role it plays in human existence.

Who it's for: Amateur (or professional) linguists; fans of the podcast A Way with Words (me). —SMS

An Image of My Name Enters America by Lucy Ives [NF]

What it is: A collection of interrelated essays that connect moments from Ives's life to larger questions of history, identity, and national fantasy,

Who it's for: Fans of Ives, one of our weirdest and most wondrous living writers—duh; anyone with a passing interest in My Little Pony, Cold War–era musicals, or The Three Body Problem, all of which are mined here for great effect. —SMS

Women's Hotel by Daniel Lavery [F]

What it is: A novel set in 1960s New York City, about the adventures of the residents of a hotel providing housing for young women that is very much evocative of the real-life legendary Barbizon Hotel.

Who it's for: Readers of Mary McCarthy's The Group and Rona Jaffe's The Best of Everything. —CK

The World in Books by Kenneth C. Davis [NF]

What it is: A guide to 52 of the most influential works of nonfiction ever published, spanning works from Plato to Ida B. Wells, bell hooks to Barbara Ehrenreich, and Sun Tzu to Joan Didion.

Who it's for: Lovers of nonfiction looking to cover their canonical bases. —SMS

Blue Light Hours by Bruna Dantas Lobato [F]

What it's about: Through the emanating blue-glow of their computer screens, a mother and daughter, four-thousand miles apart, find solace and loneliness in their nightly Skype chats in this heartstring-pulling debut.

Who it's for: Someone who needs to be reminded to CALL YOUR MOTHER! —DF

Riding Like the Wind by Iris Jamahl Dunkle [NF]

What it is: The biography of Sanora Babb, a contemporary of John Steinbeck's whose field notes and interviews with Dust Bowl migrants Steinbeck relied upon to write The Grapes of Wrath.

Who it's for: Steinbeck fans and haters alike; readers of Kristin Hannah's The Four Winds and the New York Times Overlooked column; anyone interested in learning more about the Dust Bowl migrants who fled to California hoping for a better life. —CK

Innie Shadows by Olivia M. Coetzee [F]

What it is: a work of crime fiction set on the outskirts of Cape Town, where a community marred by violence seeks justice and connection; also the first novel to be translated from Kaaps, a dialect of Afrikaans that was until recently only a spoken language.

Who it's for: fans of sprawling, socioeconomically-attuned crime dramas a la The Wire. —SMS

Dorothy Parker in Hollywood by Gail Crowther [NF]

What it is: A history of the famous wit—and famous New Yorker—in her L.A. era, post–Algonquin Round Table and mid–Red Scare.

Who it's for: Owners of a stack of hopelessly dog-eared Joan Didion paperbacks. —JHM

The Myth of American Idealism by Noam Chomsky and Nathan J. Robinson [NF]

What it is: A potent critique of the ideology behind America's foreign interventions and its status as a global power, and an treatise on how the nation's hubristic pursuit of "spreading democracy" threatens not only the delicate balance of global peace, but the already-declining health of our planet.

Who it's for: Chomskyites; policy wonks and casual critics of American recklessness alike. —DF

Mysticism by Simon Critchley [NF]

What it is: A study of mysticism—defined as an experience, rather than religious practice—by the great British philosopher Critchley, who mines music, poetry, and literature along the way.

Who it's for: Readers of John Gray, Jorge Luis Borges, and Simone Weil. —SMS

Q&A by Adrian Tomine [NF]

What it is: The Japanese American creator of the Optic Nerve comic book series for D&Q, and of many a New Yorker cover, shares his personal history and his creative process in this illustrated unburdening.

Who it’s for: Readers of Tomine’s melancholic, sometimes cringey, and occasionally brutal collections of comics short stories including Summer Blonde, Shortcomings, and Killing and Dying. —NodB

Sonny Boy by Al Pacino [NF]

What it is: Al Pacino's memoir—end of description.

Who it's for: Cinephiles; anyone curious how he's gonna spin fumbling Diane Keaton. —SMS

Seeing Baya by Alice Kaplan [NF]

What it is: The first biography of the enigmatic and largely-forgotten Algerian artist Baya Mahieddine, who first enchanted midcentury Paris as a teenager.

Who it's for: Admirers of Leonora Carrington, Hilma af Klint, Frida Kahlo, and other belatedly-celebrated women painters. —SMS

Absolution by Jeff VanderMeer [F]

What it is: A surprise return to the Area X, the stretch of unforbidding and uncanny coastline in the hit Southern Reach trilogy.

Who it's for: Anyone who's heard this song and got the reference without Googling it. —JHM

The Four Horsemen by Nick Curtola [NF]

What it is: The much-anticipated cookbook from the team behind Brooklyn's hottest restaurant (which also happens to be co-owned by James Murphy of LCD Soundsystem).

Who it's for: Oenophiles; thirty-somethings who live in north Williamsburg (derogatory). —SMS

Seeing Further by Esther Kinsky, tr. Caroline Schmidt [F]

What it's about: An unnamed German woman embarks on the colossal task of reviving a cinema in a small Hungarian village.

Who it's for: Fans of Jenny Erpenbeck; anyone charmed by Cinema Paradiso (not derogatory!). —SMS

Ripcord by Nate Lippens [NF]

What it's about: A novel of class, sex, friendship, and queer intimacy, written in delicious prose and narrated by a gay man adrift in Milwaukee.

Who it's for: Fans of Brontez Purnell, Garth Greenwell, Alexander Chee, and Wayne Koestenbaum. —SMS

The Use of Photography by Annie Ernaux and Marc Marie, tr. Alison L. Strayer [NF]

What it's about: Ernaux's love affair with Marie, a journalist, while she was undergoing treatment for cancer, and their joint project to document their romance.

Who it's for: The Ernaux hive, obviously; readers of Sontag's On Photography and Janet Malcolm's Still Pictures. —SMS

Nora Ephron at the Movies by Ilana Kaplan [NF]

What it is: Kaplan revisits Nora Ephron's cinematic watersheds—Silkwood, Heartburn, When Harry Met Sally, You've Got Mail, and Sleepless in Seattle—in this illustrated book. Have these iconic stories, and Ephron’s humor, weathered more than 40 years?

Who it’s for: Film history buffs who don’t mind a heteronormative HEA; listeners of the Hot and Bothered podcast; your coastal grandma. —NodB

[millions_email]

The Philosophy of Translation by Damion Searls [NF]

What it is: A meditation on the act and art of translation by one of today's most acclaimed practitioners, best known for his translations of Fosse, Proust, et al.

Who it's for: Regular readers of Words Without Borders and Asymptote; professional and amateur literary translators alike. —SMS

Salvage by Dionne Brand

What it is: A penetrating reevaluation of the British literary canon and the tropes once shaped Brand's reading life and sense of self—and Brand’s first major work of nonfiction since her landmark A Map to the Door of No Return.

Who it's for: Readers of Christina Sharpe's Ordinary Notes and Elizabeth Hardwick's Seduction and Betrayal. —SMS

Masquerade by Mike Fu [F]

What it's about: Housesitting for an artist friend in present-day New York, Meadow Liu stumbles on a novel whose author shares his name—the first of many strange, haunting happenings that lead up to the mysterious disappearance of Meadow's friend.

Who it's for: fans of Ed Park and Alexander Chee. —SMS

November

The Beggar Student by Osamu Dazai, tr. Sam Bett [F]

What it is: A novella in the moody vein of Dazai’s acclaimed No Longer Human, following the 30-something “fictional” Dazai into another misadventure spawned from a hubristic spat with a high schooler.

Who it's for: Longtime readers of Dazai, or new fans who discovered the midcentury Japanese novelist via TikTok and the Bungo Stray Dogs anime. —DF

In Thrall by Jane DeLynn [F]

What it is: A landmark lesbian bildungsroman about 16-year-old Lynn's love affair with her English teacher, originally published in 1982.

Who it's for: Fans of Joanna Russ's On Strike Against God and Edmund White's A Boy's Own Story —SMS

Washita Love Child by Douglas Kent Miller [NF]

What it is: The story of Jesse Ed Davis, the Indigenous musician who became on of the most sought after guitarists of the late '60s and '70s, playing alongside B.B. King, Bob Dylan, John Lennon, and more.

Who it's for: readers of music history and/or Indigenous history; fans of Joy Harjo, who wrote the foreword. —SMS

Set My Heart on Fire by Izumi Suzuki, tr. Helen O'Horan [F]

What it is: Gritty, sexy, and wholly rock ’n’ roll, Suzuki’s first novel translated into English (following her story collection, Hit Parade of Tears) follows 20-year-old Izumi navigating life, love, and music in the underground scene in '70s Japan.

Who it's for: Fans of Meiko Kawakami, Ursula K. Le Guin, and Marlowe Granados's Happy Hour. —DF

Didion & Babitz by Lili Anolik [NF]

What it is: A dual portrait of Joan Didion and Eve Babitz, who are so often compared to—and pitted against—each other on the basis of their mutual Los Angeles milieu.

Who it's for: Fans or haters of either writer (the book is fairly pro-Babitz, often at Didion's expense); anyone who has the Lit Hub Didion tote bag. —SMS

The Endless Refrain by David Rowell [NF]

What it's about: How the rise of music streaming, demonitizing of artist revenue, and industry tendency toward nostalgia have laid waste to the musical landscape, and the future of music culture.

Who it's for: Fans of Kyle Chayka, Spence Kornhaber, and Lindsay Zoladz. —SMS

Every Arc Bends Its Radian by Sergio De La Pava [F]

What it is: A mind- and genre-bending detective story set in Cali, Colombia, that blends high-stakes suspense with rigorous philosophy.

Who it's for: Readers of Raymond Chandler, Thomas Pynchon, and Jules Verne. —SMS

Something Close to Nothing by Tom Pyun [F]

What it’s about: At the airport with his white husband Jared, awaiting a flight to Cambodia to meet the surrogate mother carrying their adoptive child-to-be, Korean American Wynn decides parenthood isn't for him, and bad behavior ensues.

Who it’s for: Pyun’s debut is calculated to cut through saccharine depictions of queer parenthood—could pair well with Torrey Peters’s Detransition, Baby. —NodB

Rosenfeld by Maya Kessler [F]

What it is: Kessler's debut—rated R for Rosenfeld—follows one Noa Simmons through the tumultuous and ultimately profound power play that is courting (and having a lot of sex with) the titular older man who soon becomes her boss.

Who it's for: Fans of Sex and the City, Raven Leilani’s Luster, and Coco Mellor’s Cleopatra and Frankenstein. —DF

Lazarus Man by Richard Price [F]

What it is: The former The Wire writer offers yet another astute chronicle of urban life, this time of an ever-changing Harlem.

Who it's for: Fans of Colson Whitehead's Crook Manifesto and Paul Murray's The Bee Sting—and, of course, The Wire. —SMS

Stranger Than Fiction by Edwin Frank [NF]

What it is: An astute curveball of a read on the development and many manifestations of the novel throughout the tumultuous 20th century.

Who it's for: Readers who look at a book's colophon before its title. —JHM

Letters to His Neighbor by Marcel Proust, tr. Lydia Davis

What it is: A collection of Proust’s tormented—and frequently hilarious—letters to his noisy neighbor which, in a diligent translation from Davis, stand the test of time.

Who it's for: Proust lovers; people who live below heavy-steppers. —DF

Context Collapse by Ryan Ruby [NF]

What it is: A self-proclaimed "poem containing a history of poetry," from ancient Greece to the Iowa Workshop, from your favorite literary critic's favorite literary critic.

Who it's for: Anyone who read and admired Ruby's titanic 2022 essay on The Waste Land; lovers of poetry looking for a challenge. —SMS

How Sondheim Can Change Your Life by Richard Schoch [NF]

What it's about: Drama professor Schoch's tribute to Stephen Sondheim and the life lessons to be gleaned from his music.

Who it's for: Sondheim heads, former theater kids, end of list. —SMS

The Serviceberry by Robin Wall Kimmerer [NF]

What it is: 2022 MacArthur fellow and botanist Kimmerer, an enrolled member of the Citizen Potawatomi Nation, (re)introduces audiences to a flowering, fruiting native plant beloved of foragers and gardeners.

Who it’s for: The restoration ecologist in your life, along with anyone who loved Braiding Sweetgrass and needs a nature-themed holiday gift. —NodB

My Heart Belongs in an Empty Big Mac Container Buried Beneath the Ocean Floor by Homeless [F]

What it is: A pseudonymous, tenderly comic novel of blue whales and Golden Arches, mental illness and recovery.

Who it's for: Anyone who finds Thomas Pynchon a bit too staid. —JHM

Yoke and Feather by Jessie van Eerden [NF]

What it's about: Van Eerden's braided essays explore the "everyday sacred" to tease out connections between ancient myth and contemporary life.

Who it's for: Readers of Courtney Zoffness's Spilt Milk and Jeanna Kadlec's Heretic. —SMS

Camp Jeff by Tova Reich [F]

What it's about: A "reeducation" center for sex pests in the Catskills, founded by one Jeffery Epstein (no, not that one), where the dual phenomena of #MeToo and therapyspeak collide.

Who it's for: Fans of Philip Roth and Nathan Englander; cancel culture skeptics. —SMS

Selected Amazon Reviews by Kevin Killian [NF]

What it is: A collection of 16 years of Killian’s funniest, wittiest, and most poetic Amazon reviews, the sheer number of which helped him earn the rarefied “Top 100” and “Hall of Fame” status on the site.

Who it's for: Fans of Wayne Koestenbaum and Dodie Bellamy, who wrote introduction and afterword, respectively; people who actually leave Amazon reviews. —DF

Cher by Cher [NF]

What it is: The first in a two-volume memoir, telling the story of Cher's early life and ascendent career as only she can tell it.

Who it's for: Anyone looking to fill the My Name Is Barbra–sized hole in their heart, or looking for something to tide them over until the Liza memoir drops. —SMS

The City and Its Uncertain Walls by Haruki Murakami, tr. Philip Gabriel [F]

What it is: Murakami’s first novel in over six years returns to the high-walled city from his 1985 story "Hard-Boiled Wonderland and the End of the World" with one man's search for his lost love—and, simultaneously, an ode to libraries and literature itself.

Who it's for: Murakami fans who have long awaited his return to fiction. —DF

American Bulk by Emily Mester [NF]

What it's about: Reflecting on what it means to "live life to the fullest," Mester explores the cultural and personal impacts of America’s culture of overconsumption, from Costco hauls to hoarding to diet culture—oh my!

Who it's for: Lovers of sustainability; haters of excess; skeptics of the title essay of Becca Rothfeld's All Things Are Too Small. —DF

The Icon and the Idealist by Stephanie Gorton [NF]

What it is: A compelling look at the rivalry between Margaret Sanger, of Planned Parenthood fame, and Mary Ware Dennett, who each held radically different visions for the future of birth control.

Who it's for: Readers of Amy Sohn's The Man Who Hated Women and Katherine Turk's The Women of NOW; anyone interested in the history of reproductive rights. —SMS

December

Rental House by Weike Wang [F]

What it's about: Married college sweethearts invite their drastically different families on a Cape Code vacation, raising questions about marriage, intimacy, and kinship.

Who it's for: Fans of Wang's trademark wit and sly humor (see: Joan Is Okay and Chemistry); anyone with an in-law problem.

Woo Woo by Ella Baxter [F]

What it's about: A neurotic conceptual artist loses her shit in the months leading up to an exhibition that she hopes will be her big breakout, poking fun at the tropes of the "art monster" and the "woman of the verge" in one fell, stylish swoop.

Who it's for: Readers of Sheena Patel's I'm a Fan and Chris Kraus's I Love Dick; any woman who is grateful to but now also sort of begrudges Jenny Offil for introducing "art monster" into the lexicon (me). —SMS

Berlin Atomized by Julia Kornberg, tr. Jack Rockwell and Julia Kornberg [F]

What it's about: Spanning 2001 to 2034, three Jewish and downwardly mobile siblings come of age in various corners of the world against the backdrop of global crisis.

Who it's for: Fans of Catherine Lacey's Biography of X and Joshua Cohen's The Netanyahus. —SMS

Sand-Catcher by Omar Khalifah, tr. Barbara Romaine [F]

What it is: A suspenseful, dark satire of memory and nation, in which four young Palestinian journalists at a Jordanian newspaper are assigned to interview an elderly witness to the Nakba, the violent 1948 expulsion of native Palestinians from Israel—but to their surprise, the survivor doesn’t want to rehash his trauma for the media.

Who it’s for: Anyone looking insight—tinged with grim humor—into the years leading up to the present political crisis in the Middle East and the decades-long goal of Palestinian autonomy. —NodB

The Shutouts by Gabrielle Korn [F]

What it's about: In the dystopian future, mysteriously connected women fight to survive on the margins of society amid worsening climate collapse.

Who it's for: Fans of Korn's Yours for the Taking, which takes place in the same universe; readers of Becky Chambers and queer-inflected sci-fi. —SMS

What in Me Is Dark by Orlando Reade [NF]

What it's about: The enduring, evolving influence of Milton's Paradise Lost on political history—and particularly on the work of 12 revolutionary readers, including Malcom X and Hannah Arendt.

Who it's for: English majors and fans of Ryan Ruby and Sarah Bakewell—but I repeat myself. —SMS

The Afterlife Is Letting Go by Brandon Shimoda [NF]

What it's about: Shimoda researches the mass incarceration of Japanese Americans during WWII, and speaks with descendants of those imprisoned, for this essay collection about the “afterlife” of cruelty and xenophobia in the U.S.

Who it’s for: Anyone to ever visit a monument, museum, or designated site of hallowed ground where traumatic events have taken place. —NodB

No Place to Bury the Dead by Karina Sainz Borgo, tr. Elizabeth Bryer [F]

What it's about: When Angustias Romero loses both her children while fleeing a mysterious disease in her unnamed Latin American country, she finds herself in a surreal, purgatorial borderland where she's soon caught in a power struggle.

Who it's for: Fans of Maríana Enriquez and Mohsin Hamid. —SMS

The Rest Is Silence by Augusto Monterroso, tr. Aaron Kerner [F]

What it is: The author of some of the shortest, and tightest, stories in Latin American literature goes long with a metafictional skewering of literary criticism in his only novel.

Who it's for: Anyone who prefers the term "palm-of-the-hand stories" to "flash fiction." —JHM

Tali Girls by Siamak Herawi, tr. Sara Khalili [F]

What it is: An intimate, harrowing, and vital look at the lives of girls and women in an Afghan mountain village under Taliban rule, based on true stories.

Who it's for: Readers of Nadia Hashimi, Akwaeke Emezi, and Maria Stepanova. —SMS

Sun City by Tove Jansson, tr. Thomas Teal [F]

What it's about: During her travels through the U.S. in the 1970s, Jansson became interested in the retirement home as a peculiarly American institution—here, she imagines the tightly knit community within one of them.

Who it's for: Fans of Jansson's other fiction for adults, much of which explores the lives of elderly folks; anyone who watched that documentary about The Villages in Florida. —SMS

Editor's note: We're always looking to make our seasonal book previews more useful to the readers, writers, and critics they're meant to serve. Got an idea for how we can improve our coverage? Tell me about it at sophia@themillions.com.

[millions_email]

Joan Chase: Our Childhood Edens and Lost Orchards of Memory

This post was produced in partnership with Bloom, a literary site that features authors whose first books were published when they were 40 or older.

1.

Every year I teach Mary Shelley's novel Frankenstein to first-year college students, who can’t quite believe it was written by a girl their age. How could someone so young create a work so furiously complex, alive with the energies of need, anger, love, and alienation? But then, who would have known freakishness so well as a bookish girl in a male-dominated world, secretly convinced she’d killed the mother she never knew? “When I looked around I saw and heard of none like me,” the Creature tells his creator, Victor Frankenstein. “Was I, then, a monster, a blot upon the earth, from which all men fled and whom all men disowned?” Yet the Creature’s own consciousness makes avoiding this pain impossible, and, like any writer, he is drawn to examine it: “[O]f what a strange nature is knowledge!” he tells Victor. “It clings to the mind, when it has once seized on it, like a lichen on the rock.” Knowledge brings pain. But knowledge -- and its exploration, in stories -- is irresistible.

The sorrowing rage of a precocious daughter who felt spurned by her father and responsible for her mother’s death certainly drives the novel. But its origins aren’t quite that simple. Frankenstein was a book Mary Shelley had to write, for reasons she might never have been able to explain. That inward pressure is part of the alchemy that makes any novel an even bigger and stranger experience for its writer (and its reader) than the writer knows. While we may sometimes connect the real Mary Shelley with her brooding Creature, Frankenstein's enduring allure comes from a much more mysterious place -- an imaginative energy born of transgression, memory, fear, and desire, which may spring from real life but isn’t ever fully bound by it. That energy communicates itself to us, elevating the idea of the novel itself -- to a heightened sensory tour of a recognizable human reality, fundamentally not responsible to any laws but its own.

Joan Chase, whose first novel was published when she was 47, is a writer whose work demonstrates this energy. She’s won many awards (including a Guggenheim, a Whiting Writers’ Award, the Janet Heidinger Kafka Prize, and PEN America’s Ernest Hemingway Foundation Award), and, according to one online source, is “still writing.” Yet she’s a shy, little-known presence in the modern literary world, with no webpage or Twitter feed. When confronted with so specific a fictional realm as Chase’s, readers accustomed to copious author bios and Internet availability will find themselves baffled. Yet her fiction demonstrates just how little “authorial intent” or “biography” can matter. Chase teaches us what it means for a writer to submit herself to the story, letting fiction and fact alchemize according to the needs of the created world on the page and following wherever that world’s logic leads, regardless of literal “truth.”

2.

Recently reissued by NYRB Classics, Chase’s first novel, During the Reign of the Queen of Persia (1983), is narrated by a collective “we,” a group of sisters and cousins living in a matriarchal farm household in northern Ohio in the 1950s. “For as long as we could remember,” they tell us, “we had been together in the house which established the center of the known world.” Celia, Jenny, Anne, and Katie are cousins and sisters, “like our mothers, who were sisters” and who are all living in the house together at one time or another. “Sometimes we watched each other, knew differences,” they say. “But most of the time it was as though the four of us were one and we lived in days that gathered into one stream of time, undifferentiated and communal.”

The girls’ days are marked by farm-kid pleasures (kittens under the porch, playing in the hayloft with a hidden deck of cards) and violence (fighting with each other and their boy cousin, the sinister Rossie) and family crises that descend like weather: cancer, marital discord, courtship and impending marriage, abuse and making-up again. Family members come and go and come again until three generations -- parents and their daughters, and the daughters’ husbands and children -- have settled into the house. At every turn the girls feel knit deeper into the place:

Peaceable, we waited on the porch in the dappling noontime. In the Mason jars stacked up dusty and fly-specked on the side shelves, in the broken-webbed snowshoes hung there, the heap of rusty hinged traps waiting this long time to be oiled and set to catch something in the night, was the visible imprint of the past we were rooted in.

The girls’ world is presided over by a fierce, dominating goddess -- their grandmother Lil. Nicknamed the eponymous “Queen of Persia,” Lil has been working her entire life, starting as a scrawny 11-year-old nanny for a neighbor with tuberculosis. Even an inheritance from a rich uncle, which enables her to buy a farm for herself, doesn’t soften her sense of grievance at the world. “She vowed it was peculiar,” say the girls, “her father spent his life in the West, searching for oil, when all along it was right out back under the corn crib. Now wasn’t that just like a man? Like life.” Focused in old age on her own self-protection, Lil widens her angry judgment of the world to include her daughters and granddaughters. Sometimes she condemns them, but sometimes she protects them. When her oldest daughter Grace dies of cancer, Gram squares off against Grace’s feckless husband, Neil. Yet at the novel’s end -- after making a decision that shocks the reader -- Gram snorts, “What did we ever have around here but dying and fighting? Work and craziness.” For the girls, Gram models womanhood as sheer cussedness and endurance, a “soiled and faded apron and her exhausted face, marked like an old barn siding that had withstood blasts and abuse of all kinds, beyond any expression other than resignation and self-regard.”

The man for whom Gram reserves most of her fury is her husband, Jacob, a stern Amish outcast who “was bigger than all the other men we saw who came around the farm...it was a bigness of bone, as though he were solid calcium with only skin stretched over him.” Cursing at the cows, backhanding Rossie into the barn wall for smashing eggs, and changing his long underwear only a few times a year, Grandad is a dark force of nature whose inability to interpret or express his own emotions makes him terrifying but, initially to Gram as a young woman, alluring:

Every night his eyes were watching, wanting her and letting her see it in him; but he wouldn’t touch her…though when she would pass close beside him she would hear his breathing, harsh and quick. It nearly drove her wild and her mind came to dwell on him nearly every second. Sometimes, when she lifted up the handle of the stove to stir the wood, the glutted, ashy coals crumbled at the slight touch and something inside her seemed to fragment in the same way.

Eventually, marriage -- marked by furtive, rape-like sex and Jacob’s long absences -- bends Gram’s desire into a thick club of anger, aggression, and dark humor with which she attacks everyone around her, and herself:

I seen more damned men than you would believe drinking themselves crazy, killing each other over nothing. And their women dying with babies or something else unnecessary. But you can’t tell them. I’m through trying. You can’t tell a young gal nothing, nor an older one neither. Not anything she don’t want to hear.

3.

Watching Gram hang on to her life exactly as it is -- remaining married to a man she hates, stashing her money under the floorboards, and shaking up her family with daily small cruelties -- makes the reader wonder: in a world that thwarts women, what makes a woman also thwart herself, surrendering to meanness and pushing against a hard life in a way that only makes it harder? What’s the source of that particularly Midwestern passive aggression, self-sabotage, and buried rage? And why hate the one who gets away from it all -- in this case Aunt Elinor, a successful New York career woman whose efforts to care for her dying sister are mocked even as they are relied upon? “Aunt Elinor looked patient, as one who had seen a wider world,” the girls observe, “one she constantly made visible to the rest of us -- accepting the fact that a wider world might mean a weaker place in the old one.” Why love a place where the ordinary marvels of life -- “The wet orchard grass and briers gleamed like washed planking, while above, the branches held green sails to the wind” -- are braided with such pain?

When you are immersed in Joan Chase’s writing, that love seems wholly inevitable. In her review of During the Reign of the Queen of Persia, Margaret Atwood described the girls’ connection to this place:

Will the ‘we,’ having known a childhood so all-enveloping, so histrionic and so collective, ever be able to resolve itself successfully into four separate ‘I’s? For despite the horror of some of the events they witness, the children’s life at Gram’s is fascinating and addictive, and they live with an intensity and gusto that prevent their final vision from being a bleak one.

Indeed, something in the girls cleaves to their “flamboyantly, joylessly unpredictable” grandmother, no matter what:

When we are grown up and have been through everything, we’ll be like that. We’ll order kittens drowned by the bagful. Then at night we’ll dress in our silken best, pile on jewels and whiz off to parties, bring home prizes for the family. We’ll bet on horses.

This thread of resilience brightens the otherwise dark weather of this novel, which nevertheless isn’t forced or melodramatic -- it’s only doing what it must, only being what it is. Lacking answers to the questions we might ordinarily ask the author -- Is this your family? Are you saying something about women and passive-aggression here? -- we fall back on the novel itself and on our own reactions, delving deeper into the territory of self-investigation. Which is to say, into literature.

Like Marilynne Robinson's Housekeeping, which was published three years earlier, During the Reign of the Queen of Persia is poised on the border between strict realism and something like a dream. If the governing element of Robinson’s novel is water -- the frozen lake, the drowned train -- Chase’s novel is of the soil. Rooted in landlocked northern Ohio, it is replete with cluttered farmhouses and barns and deer stealing windfall apples from the orchard. Yet its effects are never showy or awkward, never just rural Gothic cliché. Like William Faulkner, whom Chase admires, this is novelistic imagination with no elaborate scaffolding between reader and author -- just direct immersion in a stream of subjectivity and life we come to know through that immersion itself. In this, the novel echoes its subjects: terrifying, marvelous, and memorable things happen here, and that’s just how it is -- here in this dark Midwestern Eden, with its gnarled and faithful apple trees.

4.

Chase found an early center of gravity in a large family homestead in rural Ohio like the one in Queen of Persia. “[I]t was wonderful,” she has said, “to have so much family around me.” On an “Ohioana Authors” radio program, she said, “When I began to write what became During the Reign of the Queen of Persia, I didn’t decide on Ohio as the setting, Ohio was just there, my imaginative heartland. It was the land of my childhood and from my perspective the most lovely and thrilling place in the world.”

These biographical statements (among the few Chase has made) don’t account for the elements of Queen of Persia that are less than “lovely.” But they don’t really need to; we all know that what is “true” doesn’t always make the best story. A writer must let the emotional qualities and images on the page shape the story according to her own emerging logic. This means that tracing a writer’s “biography” in a novel can be difficult. Particularly for the writer herself. And that, too, is perhaps as it should be.

Chase’s later works return to themes similar to Queen of Persia, although in more diffuse, experimental ways. Her second novel, The Evening Wolves (1989) explores how a feckless, wandering father warps his daughters’ lives. Francis Clemmons is charming and fierce, self-centered and often irresistible. The first-person narration (traded among his three children and second wife) is precise and pithy, rooting us in particular bodies and subjectivities: “My hair is straight, quiet hair,” young daughter Ruthann declares, “and my head feels peaceful, at least where it shows.” Elsewhere she tells how a boy “started rubbing my bones, their stone hearts luminous in the dark, binding me like stays.” Unlike Persia, the novel feels inconclusive, with an open-endedness that is employed to better effect in Chase’s short fiction.

Gathered in Bonneville Blue (1991), Chase’s stories are strange and shapely, centered around striking images from down-at-heel rural worlds reminiscent of Persia’s barns and backroads. Sally in “Crowing” accompanies a cranky old man around his barn: “People say farm animals know when the hog butcher is coming. Somehow. Even the day before, they will be restive, off their feed, as though word of the appointment has reached them.” Here, too, women are yearning yet uncertain how to act. In the lyrical “The Harrier,” an unhappily married woman dreams of a younger man:

I didn’t go with him up into that bed in the forest, not in the end, although as I said, in that winter of cold and driving spikes of ice he seemed to slam against my bedroom window all night like some night bird wanting in. But I chose to lie on, hugging the curve of my husband’s unyielding back, dreaming the smell that is feverish and rank, the distillation of roots and vines newly turned over.

5.

Like Elena Ferrante, whose novels of growing up in midcentury Naples have drawn fresh attention this fall -- and who writes from behind an inviolable pseudonym -- Joan Chase disrupts the links we seek between a writer’s life and her art to let her work stand alone in the public eye. Of course, Joan Chase is her real name. But her relative silence, while thwarting readers’ curiosity, serves us as Ferrante’s pseudonymity does by sending us back to the work, which stands on its own -- enigmatic, dark, and gorgeous.

Reading Chase, Ferrante, and Mary Shelley all together reignites my curiosity about women, writing, and boldness. What interior permissions, or exterior disguises, or at-long-last states of peace and determination must a woman attain to in order to speak the story that wants to take shape, whatever that shape may be? I’m wondering, too, about the relationship between personal privacy and the kind of boldness we need to do our work. In the Internet age, Ferrante’s pseudonym and Chase’s quietness both suggest strategies to address that issue: if you want to avoid complaining family members, or earnest reviewers asking you about “which parts are autobiographical,” or random readers’ emails, short-circuiting the link between you and the public might help. Maintaining privacy might also quiet interior voices that insist a good daughter would never write this. Seeking recognition is just not what we do in this family. If you get the wrong kind of attention, it’s your own fault.

During the Reign of the Queen of Persia does make me wonder about Chase’s family’s reaction: whether they recognized themselves, whether they objected, whether they half-resented the one whose success they also envied. But ultimately, it’s not our business. It is enough that Joan Chase brought into the world a novel so vivid, risky, and beautiful, and that from it we can learn to trust our stories -- to finger the jagged grain of those trees in our childhood Edens, those lost orchards of memory -- and let them take us where they need to go.

Undomesticated: On Joan Chase’s During the Reign of the Queen of Persia

1.

Consider that phrase, “domestic fiction.” So close to “domesticated,” it carries the connotation of a house-broken pet: eager to please, discreet, companionable, sulky but essentially submissive. It's a usefully misleading cover for a mode that is more often fraught and claustrophobic. When Anthony Lane describes Henry James's Portrait of a Lady as a “disturbance of the peace” and a “horror story,” he could be talking about domestic fiction generally.

Reissued this month as a NYRB Classic, Joan Chase's During the Reign of the Queen of Persia won the PEN/Hemingway Prize for First Fiction in 1983, two years after Marilynne Robinson's Housekeeping and one year after Bobbie Ann Mason's Shiloh and Other Stories. Upon publication, those three novels were individually considered as feminist reworkings of domestic fiction -- as political statements -- though each author had ambitions that extended into questions of the self against the demands of community.

The Jewish philosopher Emmanuel Lévinas once answered the question “What does it mean to be Jewish?” by saying:

To be Jewish is not a particularity; it is a modality. Everyone is a little bit Jewish, and if there are men on Mars, one will find Jews among them. Moreover, Jews are people who doubt themselves, who in a certain sense, belong to a religion of unbelievers. God says to Joshua, “I will not abandon you nor will I let you escape.”

In, Housekeeping and Chase's first novel, as well as Paula Fox's The Widow's Children and Hilary Mantel's Every Day is Mother's Day, the Family is a kind of Lévinasian paradox: its members will not abandoned nor will they be allowed to escape. These fragile communities are knitted together by doubt, intimidation, suspicion, timidity, and egotism.

To better understand why they stay in co-dependent relationships, Fox, Mantel, and Chase anatomize their protagonists' intellectual contradictions and follies stoically, without a hint of sentimentality. If there is an arch-theme to the genre, it would be the way each of us can become ensnared by our own solipsism. In The Widow's Children, one character stays in an impoverished, acrimonious marriage because she has convinced herself of her own superiority over her condition, “that they were only 'broke,' that rescue was on the way -- always on the way.”

2.

The “Queen of Persia” is a grandmother in a small Ohio farming town. She has four daughters. Her four granddaughters are all born within two years of each other to mismatched parents. The male characters -- the malevolent grandfather, one hapless trumpet-playing uncle, and another enigmatic uncle who is a failed writer -- are palpably uneasy around their daughters and wives. The women assume the responsibility of preparing the young girls for the austere life they will inherit.

Chase's novel is narrated by the four young granddaughters, “we.” This unorthodox conceit works subtly, but it also leads to a telling choice. There is no reference to “Mom” or “Dad,” only to Aunt Libby and Uncle Dan, insisting on a tone of estrangement between the children and their parents. When their individual anonymity is disrupted, one of the girls is lifted out of the group and treated like an outsider. Occasionally, the narrators skip over subjects that perhaps are not comprehensible for pre-teen girls. (They have a sexual encounter with a cousin that is obliquely depicted.)

The tone is cautiously wistful, as if this past still has a grip on its survivors. A signal choice in this novel is the manipulation of time. During the Reign of the Queen of Persia and Toni Morrison's Sula (1977) cover the same territory, well, literally. Sula opens with a landscape of rural Ohio:

In that place, where they tore the nightshade and blackberry patches from their roots to make room for the Medallion City Golf Course, there was once a neighborhood. It stood in the hills above the valley town of Medallion and spread all the way to the river. It is called the suburbs now, but when black people lived there it was called the Bottom. One road, shaded by beeches, oaks, maples, and chestnuts, connected it to the valley.

This is the beginning of Chase's novel:

In northern Ohio there is a county of some hundred thousand arable acres which breaks with the lake region flatland and begins to roll and climb, and to change into rural settings: roadside clusters of houses, small settlements that repose on the edge of nowhere […] These traces of human habitation recede, balanced by the luxuriant curving hills, cliffs like lounging flanks, water shoots that rapidly lose themselves in gladed ravines.

As opposed to Morrison's description, the present doesn't dominate the memory of 1950s Ohio; the past has been carefully circumscribed. Morrison's historical landscape is besieged by real-estate developers and social forces of change. Chase's landscape doesn't register the present. It appears elemental, hardly concerned with human beings at all.

The first chapter of During the Reign is set in motion when the oldest granddaughter, Celia, experiences puberty, “a miracle and a calamity.” Sexuality shuffles the motives of everyone around the young girls, who only dimly seem to understand why. Her mother, Aunt Libby, becomes fiercely devoted to making sure she doesn't ruin her chances for marriage. A half dozen men woo her. Her fiancé later betrays her. In what feels like 10 pages, Celia's adolescent beauty and verve quietly shrink: “[Her mother] still fretted over Celia, a set habit, focusing now on her health, for rather quickly the bloom of Celia's face and figure was gone. She looked wilted by misfortune.” Celia marries the quietly pining boy she wasn't interested in and moves to Texas.

When the father of two of the girls visits the farm, a large “country-style” breakfast sparks memories of his own childhood. After breakfast, the girls wait for him in the barn. Their private ritual the narrators describe is a re-enactment of his childhood. He performs the role of a Mr. Higgenbottom, a teacher “as mean as Silas Marner, as severe as God, and as relentless as the devil.” He gives each girl a word to spell. Eventually, the girls misspell “symbol” and “conscience” and he whips them with a stick. They rationalize that he hits them less hard than he hits his own hand.

The father, Neil, eventually let them go:

We are released then, forget again, and begin to descend the levels of the barn, down through the shafts of sunlight, and then we run off down the pasture lane into the woods, walking by the stony shallow stream until it is deeper and it runs clean. We slide into the water; our dresses fill and float about us as though we have been altered into water lilies.

Neil, though, follows them to the stream, where they tackle him and pile onto him. Restless and mysterious, he seems to vanish into the air, and the girls call his name. The narrators then say, “Then we forget again, dreaming.”

This odd father-daughter set piece is echoed in a later Chase novel, The Evening Wolves (1990). The father in that novel imitates the big bad wolf. Drawn to the dangerous wolf, the daughters are unable to resist approaching and being mauled by the wolf. Both scenes, with the apologetic victim and the physically violent adult, are unsettling.

The father-uncle and the girls are caught in a pantomime of private history that they can't seem to extricate themselves from. Like the abusive grandfather lurking in the background, Neil allows the grief of his own past to impinge on his own daughters' youth. Their childhood isn't innocent and it isn't painless, Chase suggests, but he shouldn't add to their suffering.

3.

The novel then spools backward, to the marriage of the grandmother and grandfather, a man hardened by his Depression-era struggles. He is an abusive drunk who slowly recedes to a bench in the barn, among the cows that he is dedicated to. He sells off the cows silently and dies, un-mourned.

For the first three-fourths of the novel, the girls have only touched on the trauma that has shaped their young lives, as if their consciousness has ricocheted off it. The reader learns that Grace, mother to two of the girls, has already died from cancer by the time Celia is married in the first chapter.

The novel tests an old cliché -- that the dying can teach us how better to live -- before the narrators discard it. They also reject the faith-based consolations of their Aunt, a Christian Scientist.

None of us sang, our sorrow accomplished. We heard the footsteps of the men who carried the coffin and the closing of the car doors. We went outside with the others, blinking our eyes as if we'd walked into first light. Without a comprehensible past or imaginable expectations, we had entered into another lifetime. We held hands.

That fragile and incomprehensible past looms in this story, a centripetal force in the narrative of their lives. The painful recollection of her slow death resonates throughout the house. The gurgling sound that Grace makes during one of her last nights, as she tries to breathe, is the same sound the sink drain makes.

Amy Hungerford has argued that Robinson's Housekeeping is preoccupied with how grief paradoxically enlarges the memory of the dead and starves the self's presence. Alternately, the group chorus of During the Reign of the Queen of Persia seem untethered by time, reordering events and maintaining the inscrutability of their own motives. Unbound from a linear construction of time, this group of agnostics are connected by the tenuous thread of Lévinasian doubt and by grief.

One reason that Chase has slipped into obscurity, while her rough contemporaries Robinson, Mason, and Mantel have ascended, is the relative infrequency with which she publishes. Seven years elapsed between During the Reign of the Queen of Persia and The Evening Wolves. It has been 23 years since her short-story collection Bonneville Blue.

“The success of Persia was part of what made it difficult for me to begin a second novel,” she told Contemporary Authors Online. “But I think just being published was equally constraining. For the first time I was aware of an audience as an integral part of the process which makes a book a book. After that it was harder for me to focus on my material and fictional intentions without hearing other voices and responses.”

I also suspect that her lack of productivity owes something to her lapidary style and unhurried structure. Near the end of the novel, the Queen makes arrangements concerning the house, which she keeps secret from the entire family: “We were as separated from her,” the narrators say, “as always, living on there, awaiting her decisions, with everything that happened heightened with the poignancy and solemnity of an old tale.” That poignancy and solemnity is the effect of deliberate, patient craftsmanship. Moreover, the craftsmanship here is consummate.

We the Narrators

On a desert plain out West, the Lone Ranger and Tonto are surrounded by a band of Indians, all of them slowly closing in. Sunlight reflects off tomahawks. War paint covers furious scowls. “Looks like we’re done for, Tonto,” says the Lone Ranger, to which Tonto replies, “What do you mean ‘we,’ white man?”

That old joke raises a question other than its own punch line. Why would anyone decide to write a novel in first-person plural, a point of view that, like second-person, is often accused of being nothing but an authorial gimmick? Once mockingly ascribed to royalty, editors, pregnant women, and individuals with tapeworms, the “we” voice can, when used in fiction, lead to overly lyrical descriptions, time frames that shift too much, and a lack of narrative arc.

In many cases of first-person plural, however, those pitfalls become advantageous. The narration is granted an intimate omniscience. Various settings can be shuffled between elegantly. The voice is allowed to luxuriate on scenic details. Here are a few novels that prove first-person plural is more of a neat trick than a cheap one.

The Virgin Suicides by Jeffrey Eugenides

Prior to the publication of The Virgin Suicides, most people, when asked about first-person plural, probably thought of William Faulkner’s “A Rose for Emily.” This novel changed that. A group of men look back on their childhood in 1970s suburban Michigan, particularly “the year of the suicides,” a time when the five Lisbon sisters took turns providing the novel its title. Most remarkable about Eugenides’s debut is not those tragic events, however, but the narrative voice, so melancholy, vivid, deadpan, and graceful in its depiction not only of the suicides but also of adolescent minutiae. Playing cards stuck in bicycle spokes get as much attention as razor blades dragged across wrists. Throughout the novel, Eugenides, aware of first-person plural’s roots in classical drama, gives his narrators functions greater than those of a Greek chorus. They don’t merely comment on the action, provide background information, and voice the interiority of other characters. The collective narrators of The Virgin Suicides are really the protagonists. Ultimately their lives prove more dynamic than the deaths of the sisters. “It didn’t matter in the end how old they had been, or that they were girls, but only that we had loved them, and that they hadn’t heard us calling.”

Our Kind by Kate Walbert

This title would work for just about any book on this list. A collection of stories interconnected enough to be labeled a novel, Our Kind is narrated by ten women, suburban divorcees reminiscent of Cheever characters.

We’ve seen a lot. We’ve seen the murder-suicide of the Clifford Jacksons, Tate Kieley jailed for embezzlement, Dorothy Schoenbacher in nothing but a mink coat in August dive from the roof of the Cooke’s Inn. We’ve seen Dick Morehead arrested in the ladies’ dressing room at Lord & Taylor, attempting to squeeze into a petite teddy. We’ve seen Francis Stoney gone mad, Brenda Nelson take to cocaine. We’ve seen the blackballing of the Steward Collisters. We’ve seen more than our share of liars and cheats, thieves. Drunks? We couldn’t count.

That passage exemplifies a technique, the lyrical montage, particularly suited to first-person plural. Each perspective within a collective narrator is a mirror in the kaleidoscope of story presentation. To create a montage all an author has to do is turn the cylinder. Walbert does so masterfully in Our Kind.

During the Reign of the Queen of Persia by Joan Chase

“There were the four of us — Celia and Jenny, who were sisters, Anne and Katie, sisters too, like our mothers, who were sisters.” In her New York Times review, Margaret Atwood considered this novel, narrated by those four cousins, to be concerned with “the female matrix,” comparing it to works by Anne Tyler and Marilynne Robinson. First-person plural often renders itself along such gender matrices. This novel is unique in that its single-gender point of view is not coalesced around a subject of the opposite gender. Its female narrators examine the involutions of womanhood by delineating other female characters. Similar in that respect to another first-person-plural novel, Tova Mirvis’s The Ladies Auxiliary, During the Reign of the Queen of Persia, taking an elliptical approach to time, braids its young narrators’ lives with those of the other women in their family to create a beautifully written, impressionistic view of childhood.

The Jane Austen Book Club by Karen Joy Fowler

Novels written in first-person plural typically have one of four basic narrative structures: an investigation, gossip, some large and/or strange event, and family life. The Jane Austen Book Club uses all four of those structures. The novel manages to do so because its overall design is similar to that of an anthology series. Within the loose framework of a monthly Jane Austen book club, chapters titled after the respective months are presented, each focusing on one of the six group members, whose personal stories correspond to one of Austen’s six novels. The combinations of each character with a book, Jocelyn and Emma, Allegra and Sense and Sensibility, Prudie and Mansfield Park, Grigg and Northanger Abbey, Bernadette and Pride and Prejudice, Sylvia and Persuasion, exemplify one of the novel’s most significant lines. “Each of us has a private Austen.” Moreover, such an adage’s universality proves that, even when first-person plural refers to specific characters, the reader is, however subconsciously, an implicit part of the point of view.

The Notebook by Agota Kristof

If one doesn’t include sui generis works such as Ayn Rand’s Anthem — a dystopian novella in which the single narrator speaks in a plural voice because first-person-singular pronouns have been outlawed — Kristof’s The Notebook, narrated by twin brothers, contains the fewest narrators possible in first-person-plural fiction. Its plot has the allegorical vagueness of a fable. Weirder than Eleanor Brown’s The Weird Sisters, another first-person-plural novel narrated by siblings, the brothers in The Notebook are taken by their mother from Big Town to Little Town, where they move in with their grandmother. In an unidentified country based on Hungary they endure cruelty and abuse during an unidentified war based on World War II. To survive they grow remorselessly cold. Kristof’s use of first-person plural allows her to build a multifaceted metaphor out of The Notebook. The twins come to represent not only how war destroys selfhood through depersonalization but also how interdependence is a means to resist the effects of war.

The Autumn of the Patriarch by Gabriel Garcia Marquez

In the same way narrators can be reliable and unreliable, collective narrators can be defined and undefined. The narrators in this novel include both parts of that analogy. They’re unreliably defined. Sometimes the narrators are the people who find the corpse of the titular patriarch, an unnamed dictator of an unnamed country, but sometimes the people who find the corpse are referred to in third-person. Sometimes the narrators are the many generations of army generals. Sometimes the narrators are the former dictators of other countries. Sometimes the point of view is all-inclusive, similar to the occasional, God-like “we” scattered through certain novels, including, for example, Jim Crace’s Being Dead, E.L. Doctorow’s Ragtime, and Paul Auster’s City of Glass. Even the dictator, periodically and confusingly, uses the royal “we.” For the most part, however, the collective narrator encompasses every citizen ruled by the tyrannical despot, people who, after his death, are finally given a voice.

The Buddha in the Attic by Julie Otsuka

What about first-person plural lends itself so well to rhythm? Julie Otsuka provides an answer to that question with The Buddha in the Attic. In a series of linked narratives, she traces the lives of a group of women, including their journey from Japan to San Francisco, their struggles to assimilate to a new culture, their internment during World War II, and other particulars of the Japanese-American experience. “On the boat we were mostly virgins. We had long black hair and flat wide feet and we were not very tall,” the novel begins. “Some of us had eaten nothing but rice gruel as young girls and had slightly bowed legs, and some of us were only fourteen years old and were still young girls ourselves.” Although the narrators are, for the most part, presented as a collective voice, each of their singular voices are dashed throughout the novel, in the form of italicized sentences. It is in that way Otsuka creates a rhythm. The plural lines become the flat notes, singular lines the sharp notes, all combining to form a measured beat.

Then We Came to the End by Joshua Ferris

For his first novel’s epigraph, Ferris quotes Ralph Waldo Emerson, “Is it not the chief disgrace of this world, not to be a unit; — not to be reckoned one character; — not to yield that peculiar fruit which each man was created to bear, but to be reckoned in the gross, in the hundred, or the thousand, of the party, the section, to which we belong...” The line nicely plays into this novel about corporate plurality. At an ad agency in Chicago post-dot-com boom, the employees distract themselves from the economic downturn with office hijinks, stealing each other’s chairs, wearing three company polo shirts at once, going an entire day speaking only quotes from The Godfather. The narrative arc is more of a plummet. Nonetheless, Ferris manages to turn a story doomed from the beginning — the title, nabbed from DeLillo’s first novel, says it all — into a hilarious and heartfelt portrait of employment. Ed Park’s Personal Days, somewhat overshadowed by the critical success of this novel, uses a similar collective narrator.

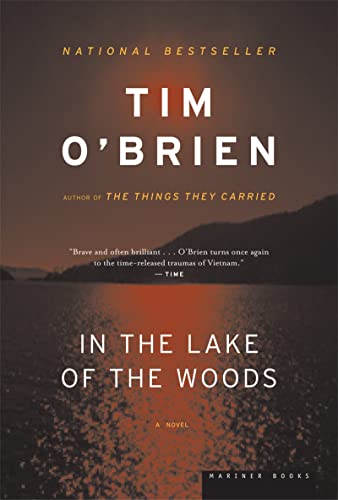

The Fates Will Find a Way by Hannah Pittard

Define hurdle. To be an author of one gender writing from the point of view of characters of the opposite gender investigating the life of a character of said author’s own gender. The most impressive thing about The Fates Will Find Their Way is how readily Pittard accomplishes such a difficult task. Despite one instance of an “I” used in the narration, the story is told in first-person plural by a collection of boys, now grown men, pondering the fate of a neighborhood girl, Nora Lindell, who went missing years ago. Every possible solution to the mystery of what happened to the girl — Heidi Julavits’s The Uses of Enchantment works similarly, as does Tim O’Brien’s In the Lake of the Woods — becomes a projection of the characters affected by her absence. In that way this novel exemplifies a key feature of many novels, including most on this list, narrated by characters who observe more than they participate. The narrators are the protagonists. It can be argued, for example, that The Great Gatsby is really the story of its narrator, Nick Carraway, even though other characters have more active roles. Same goes for James Salter’s A Sport and a Pastime, Clarice Lispector’s The Hour of the Star, Junot Diaz’s The Brief Wondrous Life of Oscar Wao, and Nancy Lemann’s Lives of the Saints, to name a few. What’s more important, after all, the prism or the light?