Mentioned in:

A Year in Reading: 2024

Welcome to the 20th (!) installment of The Millions' annual Year in Reading series, which gathers together some of today's most exciting writers and thinkers to share the books that shaped their year. YIR is not a collection of yearend best-of lists; think of it, perhaps, as an assemblage of annotated bibliographies. We've invited contributors to reflect on the books they read this year—an intentionally vague prompt—and encouraged them to approach the assignment however they choose.

In writing about our reading lives, as YIR contributors are asked to do, we inevitably write about our personal lives, our inner lives. This year, a number of contributors read their way through profound grief and serious illness, through new parenthood and cross-country moves. Some found escape in frothy romances, mooring in works of theology, comfort in ancient epic poetry. More than one turned to the wisdom of Ursula K. Le Guin. Many describe a book finding them just when they needed it.

Interpretations of the assignment were wonderfully varied. One contributor, a music critic, considered the musical analogs to the books she read, while another mapped her reads from this year onto constellations. Most people's reading was guided purely by pleasure, or else a desire to better understand events unfolding in their lives or larger the world. Yet others centered their reading around a certain sense of duty: this year one contributor committed to finishing the six Philip Roth novels he had yet to read, an undertaking that he likens to “eating a six-pack of paper towels.” (Lucky for us, he included in his essay his final ranking of Roth's oeuvre.)

The books that populate these essays range widely, though the most commonly noted title this year was Tony Tulathimutte’s story collection Rejection. The work of newly minted National Book Award winner Percival Everett, particularly his acclaimed novel James, was also widely read and written about. And as the genocide of Palestinians in Gaza enters its second year, many contributors sought out Isabella Hammad’s searing, clear-eyed essay Recognizing the Stranger.

Like so many endeavors in our chronically under-resourced literary community, Year in Reading is a labor of love. The Millions is a one-person editorial operation (with an invaluable assist from SEO maven Dani Fishman), and producing YIR—and witnessing the joy it brings contributors and readers alike—has been the highlight of my tenure as editor. I’m profoundly grateful for the generosity of this year’s contributors, whose names and entries will be revealed below over the next three weeks, concluding on Wednesday, December 18. Be sure to subscribe to The Millions’ free newsletter to get the week’s entries sent straight to your inbox each Friday.

—Sophia Stewart, editor

Becca Rothfeld, author of All Things Are Too Small

Carvell Wallace, author of Another Word for Love

Charlotte Shane, author of An Honest Woman

Brianna Di Monda, writer and editor

Nell Irvin Painter, author of I Just Keep Talking

Carrie Courogen, author of Miss May Does Not Exist

Ayşegül Savaş, author of The Anthropologists

Zachary Issenberg, writer

Tony Tulathimutte, author of Rejection

Ann Powers, author of Traveling: On the Path of Joni Mitchell

Lidia Yuknavitch, author of Reading the Waves

Nicholas Russell, writer and critic

Daniel Saldaña París, author of Planes Flying Over a Monster

Lili Anolik, author of Didion and Babitz

Deborah Ghim, editor

Emily Witt, author of Health and Safety

Nathan Thrall, author of A Day in the Life of Abed Salama

Lena Moses-Schmitt, author of True Mistakes

Jeremy Gordon, author of See Friendship

John Lee Clark, author of Touch the Future

Ellen Wayland-Smith, author of The Science of Last Things

Edwin Frank, publisher and author of Stranger Than Fiction

Sophia Stewart, editor of The Millions

A Year in Reading Archives: 2023, 2022, 2021, 2020, 2019, 2018, 2017, 2016, 2015, 2014, 2013, 2011, 2010, 2009, 2008, 2007, 2006, 2005

The Great Fall 2024 Book Preview

With the arrival of autumn comes a deluge of great books. Here you'll find a sampling of new and forthcoming titles that caught our eye here at The Millions, and that we think might catch yours, too. Some we’ve already perused in galley form; others we’re eager to devour based on their authors, plots, or subject matters. We hope your next fall read is among them.

—Sophia Stewart, editor

October

Season of the Swamp by Yuri Herrera, tr. Lisa Dillman [F]

What it is: An epic, speculative account of the 18 months that Benito Juárez spent in New Orleans in 1853-54, years before he became the first and only Indigenous president of Mexico.

Who it's for: Fans of speculative history; readers who appreciate the magic that swirls around any novel set in New Orleans. —Claire Kirch

The Black Utopians by Aaron Robertson [NF]

What it is: An exploration of Black Americans' pursuit and visions of utopia—both ideological and physical—that spans the Reconstruction era to the present day and combines history, memoir, and reportage.

Who it's for: Fans of Saidiya Hartman's Wayward Lives, Beautiful Experiments and Kristen R. Ghodsee's Everyday Utopia. —Sophia M. Stewart

The Third Realm by Karl Ove Knausgaard, tr. Martin Aitken [F]

What it is: The third installment in Knausgaard's Morning Star series, centered on the appearance of a mysterious new star in the skies above Norway.

Who it's for: Real Knausgaard heads only—The Wolves of Eternity and Morning Star are required reading for this one. —SMS

Brown Women Have Everything by Sayantani Dasgupta [NF]

What it is: Essays on the contradictions and complexities of life as an Indian woman in America, probing everything from hair to family to the joys of travel.

Who it's for: Readers of Durga Chew-Bose, Erika L. Sánchez, and Tajja Isen. —SMS

The Plot Against Native America by Bill Vaughn [F]

What it is: The first narrative history of Native American boarding schools— which aimed "civilize" Indigenous children by violently severing them from their culture— and their enduring, horrifying legacy.

Who it's for: Readers of Ned Blackhawk and Kathleen DuVal. —SMS

The Mighty Red by Louise Erdrich [F]

What it is: Erdrich's latest novel set in North Dakota's Red River Valley is a tale of the intertwined lives of ordinary people striving to survive and even thrive in their rural community, despite environmental upheavals, the 2008 financial crisis, and other obstacles.

Who it's for: Readers of cli-fi; fans of Linda LeGarde Grover and William Faulkner. —CK

The Position of Spoons by Deborah Levy [NF]

What it is: The second book from Levy in as many years, diverging from a recent streak of surrealist fiction with a collection of essays marked by exceptional observance and style.

Who it's for: Close lookers and the perennially curious. —John H. Maher

The Bog Wife by Kay Chronister [F]

What it's about: The Haddesley family has lived on the same West Virginia bog for centuries, making a supernatural bargain with the land—a generational blood sacrifice—in order to do so—until an uncovered secret changes everything.

Who it's for: Readers of Karen Russell and Jeff VanderMeer; anyone who has ever used the phrase "girl moss." —SMS

The Great When by Alan Moore [F]

What it's about: When an 18-year old book reseller comes across a copy of a book that shouldn’t exist, it threatens to upend not just an already post-war-torn London, but reality as we know it.

Who it's for: Anyone looking for a Sherlock Holmes-style mystery dipped in thaumaturgical psychedelia. —Daniella Fishman

The Message by Ta-Nehisi Coates [NF]

What it's about: One of our sharpest critical thinkers on social justice returns to nonfiction, nearly a decade after Between the World and Me, visiting Dakar, to contemplate enslavement and the Middle Passage; Columbia, S.C., as a backdrop for his thoughts on Jim Crow and book bans; and the Israeli-occupied West Bank, where he sees contemporary segregation in the treatment of Palestinians.

Who it’s for: Fans of James Baldwin, George Orwell, and Angela Y. Davis; readers of Nikole Hannah-Jones’s The 1619 Project and Isabel Wilkerson’s Caste, to name just a few engagements with national and racial identity. —Nathalie op de Beeck

Abortion by Jessica Valenti [NF]

What it is: Columnist and memoirist Valenti, who tracks pro-choice advocacy and attacks on the right to choose in her Substack, channels feminist rage into a guide for freedom of choice advocacy.

Who it’s for: Readers of Robin Marty’s The New Handbook for a Post-Roe America, #ShoutYourAbortion proponents, and followers of Jennifer Baumgartner’s [I Had an Abortion] project. —NodB

Gifted by Suzuki Suzumi, tr. Allison Markin Powell [F]

What it's about: A young sex worker in Tokyo's red-light district muses on her life and recounts her abusive mother's final days, in what is Suzuki's first novel to be translated into English.

Who it's for: Readers of Susan Boyt and Mieko Kanai; fans of moody, introspective fiction; anyone with a fraught relationship to their mother. —SMS

Childish Literature by Alejandro Zambra, tr. Megan McDowell [F]

What it is: A wide-ranging collection of stories, essays, and poems that explore childhood, fatherhood, and family.

Who it's for: Fans of dad lit (see: Lucas Mann's Attachments, Keith Gessen's Raising Raffi, Karl Ove Knausgaard's seasons quartet, et al). —SMS

Books Are Made Out of Books ed. Michael Lynn Crews [NF]

What it is: A mining of the archives of the late Cormac McCarthy with a focus on the famously tight-lipped author's literary influences.

Who it's for: Anyone whose commonplace book contains the words "arquebus," "cordillera," or "vinegaroon." —JHM

Slaveroad by John Edgar Wideman [F]

What it is: A blend of memoir, fiction, and history that charts the "slaveroad" that runs through American history, spanning the Atlantic slave trade to the criminal justice system, from the celebrated author of Brothers and Keepers.

Who it's for: Fans of Clint Smith and Ta-Nehisi Coates. —SMS

Linguaphile by Julie Sedivy [NF]

What it's about: Linguist Sedivy reflects on a life spent loving language—its beauty, its mystery, and the essential role it plays in human existence.

Who it's for: Amateur (or professional) linguists; fans of the podcast A Way with Words (me). —SMS

An Image of My Name Enters America by Lucy Ives [NF]

What it is: A collection of interrelated essays that connect moments from Ives's life to larger questions of history, identity, and national fantasy,

Who it's for: Fans of Ives, one of our weirdest and most wondrous living writers—duh; anyone with a passing interest in My Little Pony, Cold War–era musicals, or The Three Body Problem, all of which are mined here for great effect. —SMS

Women's Hotel by Daniel Lavery [F]

What it is: A novel set in 1960s New York City, about the adventures of the residents of a hotel providing housing for young women that is very much evocative of the real-life legendary Barbizon Hotel.

Who it's for: Readers of Mary McCarthy's The Group and Rona Jaffe's The Best of Everything. —CK

The World in Books by Kenneth C. Davis [NF]

What it is: A guide to 52 of the most influential works of nonfiction ever published, spanning works from Plato to Ida B. Wells, bell hooks to Barbara Ehrenreich, and Sun Tzu to Joan Didion.

Who it's for: Lovers of nonfiction looking to cover their canonical bases. —SMS

Blue Light Hours by Bruna Dantas Lobato [F]

What it's about: Through the emanating blue-glow of their computer screens, a mother and daughter, four-thousand miles apart, find solace and loneliness in their nightly Skype chats in this heartstring-pulling debut.

Who it's for: Someone who needs to be reminded to CALL YOUR MOTHER! —DF

Riding Like the Wind by Iris Jamahl Dunkle [NF]

What it is: The biography of Sanora Babb, a contemporary of John Steinbeck's whose field notes and interviews with Dust Bowl migrants Steinbeck relied upon to write The Grapes of Wrath.

Who it's for: Steinbeck fans and haters alike; readers of Kristin Hannah's The Four Winds and the New York Times Overlooked column; anyone interested in learning more about the Dust Bowl migrants who fled to California hoping for a better life. —CK

Innie Shadows by Olivia M. Coetzee [F]

What it is: a work of crime fiction set on the outskirts of Cape Town, where a community marred by violence seeks justice and connection; also the first novel to be translated from Kaaps, a dialect of Afrikaans that was until recently only a spoken language.

Who it's for: fans of sprawling, socioeconomically-attuned crime dramas a la The Wire. —SMS

Dorothy Parker in Hollywood by Gail Crowther [NF]

What it is: A history of the famous wit—and famous New Yorker—in her L.A. era, post–Algonquin Round Table and mid–Red Scare.

Who it's for: Owners of a stack of hopelessly dog-eared Joan Didion paperbacks. —JHM

The Myth of American Idealism by Noam Chomsky and Nathan J. Robinson [NF]

What it is: A potent critique of the ideology behind America's foreign interventions and its status as a global power, and an treatise on how the nation's hubristic pursuit of "spreading democracy" threatens not only the delicate balance of global peace, but the already-declining health of our planet.

Who it's for: Chomskyites; policy wonks and casual critics of American recklessness alike. —DF

Mysticism by Simon Critchley [NF]

What it is: A study of mysticism—defined as an experience, rather than religious practice—by the great British philosopher Critchley, who mines music, poetry, and literature along the way.

Who it's for: Readers of John Gray, Jorge Luis Borges, and Simone Weil. —SMS

Q&A by Adrian Tomine [NF]

What it is: The Japanese American creator of the Optic Nerve comic book series for D&Q, and of many a New Yorker cover, shares his personal history and his creative process in this illustrated unburdening.

Who it’s for: Readers of Tomine’s melancholic, sometimes cringey, and occasionally brutal collections of comics short stories including Summer Blonde, Shortcomings, and Killing and Dying. —NodB

Sonny Boy by Al Pacino [NF]

What it is: Al Pacino's memoir—end of description.

Who it's for: Cinephiles; anyone curious how he's gonna spin fumbling Diane Keaton. —SMS

Seeing Baya by Alice Kaplan [NF]

What it is: The first biography of the enigmatic and largely-forgotten Algerian artist Baya Mahieddine, who first enchanted midcentury Paris as a teenager.

Who it's for: Admirers of Leonora Carrington, Hilma af Klint, Frida Kahlo, and other belatedly-celebrated women painters. —SMS

Absolution by Jeff VanderMeer [F]

What it is: A surprise return to the Area X, the stretch of unforbidding and uncanny coastline in the hit Southern Reach trilogy.

Who it's for: Anyone who's heard this song and got the reference without Googling it. —JHM

The Four Horsemen by Nick Curtola [NF]

What it is: The much-anticipated cookbook from the team behind Brooklyn's hottest restaurant (which also happens to be co-owned by James Murphy of LCD Soundsystem).

Who it's for: Oenophiles; thirty-somethings who live in north Williamsburg (derogatory). —SMS

Seeing Further by Esther Kinsky, tr. Caroline Schmidt [F]

What it's about: An unnamed German woman embarks on the colossal task of reviving a cinema in a small Hungarian village.

Who it's for: Fans of Jenny Erpenbeck; anyone charmed by Cinema Paradiso (not derogatory!). —SMS

Ripcord by Nate Lippens [NF]

What it's about: A novel of class, sex, friendship, and queer intimacy, written in delicious prose and narrated by a gay man adrift in Milwaukee.

Who it's for: Fans of Brontez Purnell, Garth Greenwell, Alexander Chee, and Wayne Koestenbaum. —SMS

The Use of Photography by Annie Ernaux and Marc Marie, tr. Alison L. Strayer [NF]

What it's about: Ernaux's love affair with Marie, a journalist, while she was undergoing treatment for cancer, and their joint project to document their romance.

Who it's for: The Ernaux hive, obviously; readers of Sontag's On Photography and Janet Malcolm's Still Pictures. —SMS

Nora Ephron at the Movies by Ilana Kaplan [NF]

What it is: Kaplan revisits Nora Ephron's cinematic watersheds—Silkwood, Heartburn, When Harry Met Sally, You've Got Mail, and Sleepless in Seattle—in this illustrated book. Have these iconic stories, and Ephron’s humor, weathered more than 40 years?

Who it’s for: Film history buffs who don’t mind a heteronormative HEA; listeners of the Hot and Bothered podcast; your coastal grandma. —NodB

[millions_email]

The Philosophy of Translation by Damion Searls [NF]

What it is: A meditation on the act and art of translation by one of today's most acclaimed practitioners, best known for his translations of Fosse, Proust, et al.

Who it's for: Regular readers of Words Without Borders and Asymptote; professional and amateur literary translators alike. —SMS

Salvage by Dionne Brand

What it is: A penetrating reevaluation of the British literary canon and the tropes once shaped Brand's reading life and sense of self—and Brand’s first major work of nonfiction since her landmark A Map to the Door of No Return.

Who it's for: Readers of Christina Sharpe's Ordinary Notes and Elizabeth Hardwick's Seduction and Betrayal. —SMS

Masquerade by Mike Fu [F]

What it's about: Housesitting for an artist friend in present-day New York, Meadow Liu stumbles on a novel whose author shares his name—the first of many strange, haunting happenings that lead up to the mysterious disappearance of Meadow's friend.

Who it's for: fans of Ed Park and Alexander Chee. —SMS

November

The Beggar Student by Osamu Dazai, tr. Sam Bett [F]

What it is: A novella in the moody vein of Dazai’s acclaimed No Longer Human, following the 30-something “fictional” Dazai into another misadventure spawned from a hubristic spat with a high schooler.

Who it's for: Longtime readers of Dazai, or new fans who discovered the midcentury Japanese novelist via TikTok and the Bungo Stray Dogs anime. —DF

In Thrall by Jane DeLynn [F]

What it is: A landmark lesbian bildungsroman about 16-year-old Lynn's love affair with her English teacher, originally published in 1982.

Who it's for: Fans of Joanna Russ's On Strike Against God and Edmund White's A Boy's Own Story —SMS

Washita Love Child by Douglas Kent Miller [NF]

What it is: The story of Jesse Ed Davis, the Indigenous musician who became on of the most sought after guitarists of the late '60s and '70s, playing alongside B.B. King, Bob Dylan, John Lennon, and more.

Who it's for: readers of music history and/or Indigenous history; fans of Joy Harjo, who wrote the foreword. —SMS

Set My Heart on Fire by Izumi Suzuki, tr. Helen O'Horan [F]

What it is: Gritty, sexy, and wholly rock ’n’ roll, Suzuki’s first novel translated into English (following her story collection, Hit Parade of Tears) follows 20-year-old Izumi navigating life, love, and music in the underground scene in '70s Japan.

Who it's for: Fans of Meiko Kawakami, Ursula K. Le Guin, and Marlowe Granados's Happy Hour. —DF

Didion & Babitz by Lili Anolik [NF]

What it is: A dual portrait of Joan Didion and Eve Babitz, who are so often compared to—and pitted against—each other on the basis of their mutual Los Angeles milieu.

Who it's for: Fans or haters of either writer (the book is fairly pro-Babitz, often at Didion's expense); anyone who has the Lit Hub Didion tote bag. —SMS

The Endless Refrain by David Rowell [NF]

What it's about: How the rise of music streaming, demonitizing of artist revenue, and industry tendency toward nostalgia have laid waste to the musical landscape, and the future of music culture.

Who it's for: Fans of Kyle Chayka, Spence Kornhaber, and Lindsay Zoladz. —SMS

Every Arc Bends Its Radian by Sergio De La Pava [F]

What it is: A mind- and genre-bending detective story set in Cali, Colombia, that blends high-stakes suspense with rigorous philosophy.

Who it's for: Readers of Raymond Chandler, Thomas Pynchon, and Jules Verne. —SMS

Something Close to Nothing by Tom Pyun [F]

What it’s about: At the airport with his white husband Jared, awaiting a flight to Cambodia to meet the surrogate mother carrying their adoptive child-to-be, Korean American Wynn decides parenthood isn't for him, and bad behavior ensues.

Who it’s for: Pyun’s debut is calculated to cut through saccharine depictions of queer parenthood—could pair well with Torrey Peters’s Detransition, Baby. —NodB

Rosenfeld by Maya Kessler [F]

What it is: Kessler's debut—rated R for Rosenfeld—follows one Noa Simmons through the tumultuous and ultimately profound power play that is courting (and having a lot of sex with) the titular older man who soon becomes her boss.

Who it's for: Fans of Sex and the City, Raven Leilani’s Luster, and Coco Mellor’s Cleopatra and Frankenstein. —DF

Lazarus Man by Richard Price [F]

What it is: The former The Wire writer offers yet another astute chronicle of urban life, this time of an ever-changing Harlem.

Who it's for: Fans of Colson Whitehead's Crook Manifesto and Paul Murray's The Bee Sting—and, of course, The Wire. —SMS

Stranger Than Fiction by Edwin Frank [NF]

What it is: An astute curveball of a read on the development and many manifestations of the novel throughout the tumultuous 20th century.

Who it's for: Readers who look at a book's colophon before its title. —JHM

Letters to His Neighbor by Marcel Proust, tr. Lydia Davis

What it is: A collection of Proust’s tormented—and frequently hilarious—letters to his noisy neighbor which, in a diligent translation from Davis, stand the test of time.

Who it's for: Proust lovers; people who live below heavy-steppers. —DF

Context Collapse by Ryan Ruby [NF]

What it is: A self-proclaimed "poem containing a history of poetry," from ancient Greece to the Iowa Workshop, from your favorite literary critic's favorite literary critic.

Who it's for: Anyone who read and admired Ruby's titanic 2022 essay on The Waste Land; lovers of poetry looking for a challenge. —SMS

How Sondheim Can Change Your Life by Richard Schoch [NF]

What it's about: Drama professor Schoch's tribute to Stephen Sondheim and the life lessons to be gleaned from his music.

Who it's for: Sondheim heads, former theater kids, end of list. —SMS

The Serviceberry by Robin Wall Kimmerer [NF]

What it is: 2022 MacArthur fellow and botanist Kimmerer, an enrolled member of the Citizen Potawatomi Nation, (re)introduces audiences to a flowering, fruiting native plant beloved of foragers and gardeners.

Who it’s for: The restoration ecologist in your life, along with anyone who loved Braiding Sweetgrass and needs a nature-themed holiday gift. —NodB

My Heart Belongs in an Empty Big Mac Container Buried Beneath the Ocean Floor by Homeless [F]

What it is: A pseudonymous, tenderly comic novel of blue whales and Golden Arches, mental illness and recovery.

Who it's for: Anyone who finds Thomas Pynchon a bit too staid. —JHM

Yoke and Feather by Jessie van Eerden [NF]

What it's about: Van Eerden's braided essays explore the "everyday sacred" to tease out connections between ancient myth and contemporary life.

Who it's for: Readers of Courtney Zoffness's Spilt Milk and Jeanna Kadlec's Heretic. —SMS

Camp Jeff by Tova Reich [F]

What it's about: A "reeducation" center for sex pests in the Catskills, founded by one Jeffery Epstein (no, not that one), where the dual phenomena of #MeToo and therapyspeak collide.

Who it's for: Fans of Philip Roth and Nathan Englander; cancel culture skeptics. —SMS

Selected Amazon Reviews by Kevin Killian [NF]

What it is: A collection of 16 years of Killian’s funniest, wittiest, and most poetic Amazon reviews, the sheer number of which helped him earn the rarefied “Top 100” and “Hall of Fame” status on the site.

Who it's for: Fans of Wayne Koestenbaum and Dodie Bellamy, who wrote introduction and afterword, respectively; people who actually leave Amazon reviews. —DF

Cher by Cher [NF]

What it is: The first in a two-volume memoir, telling the story of Cher's early life and ascendent career as only she can tell it.

Who it's for: Anyone looking to fill the My Name Is Barbra–sized hole in their heart, or looking for something to tide them over until the Liza memoir drops. —SMS

The City and Its Uncertain Walls by Haruki Murakami, tr. Philip Gabriel [F]

What it is: Murakami’s first novel in over six years returns to the high-walled city from his 1985 story "Hard-Boiled Wonderland and the End of the World" with one man's search for his lost love—and, simultaneously, an ode to libraries and literature itself.

Who it's for: Murakami fans who have long awaited his return to fiction. —DF

American Bulk by Emily Mester [NF]

What it's about: Reflecting on what it means to "live life to the fullest," Mester explores the cultural and personal impacts of America’s culture of overconsumption, from Costco hauls to hoarding to diet culture—oh my!

Who it's for: Lovers of sustainability; haters of excess; skeptics of the title essay of Becca Rothfeld's All Things Are Too Small. —DF

The Icon and the Idealist by Stephanie Gorton [NF]

What it is: A compelling look at the rivalry between Margaret Sanger, of Planned Parenthood fame, and Mary Ware Dennett, who each held radically different visions for the future of birth control.

Who it's for: Readers of Amy Sohn's The Man Who Hated Women and Katherine Turk's The Women of NOW; anyone interested in the history of reproductive rights. —SMS

December

Rental House by Weike Wang [F]

What it's about: Married college sweethearts invite their drastically different families on a Cape Code vacation, raising questions about marriage, intimacy, and kinship.

Who it's for: Fans of Wang's trademark wit and sly humor (see: Joan Is Okay and Chemistry); anyone with an in-law problem.

Woo Woo by Ella Baxter [F]

What it's about: A neurotic conceptual artist loses her shit in the months leading up to an exhibition that she hopes will be her big breakout, poking fun at the tropes of the "art monster" and the "woman of the verge" in one fell, stylish swoop.

Who it's for: Readers of Sheena Patel's I'm a Fan and Chris Kraus's I Love Dick; any woman who is grateful to but now also sort of begrudges Jenny Offil for introducing "art monster" into the lexicon (me). —SMS

Berlin Atomized by Julia Kornberg, tr. Jack Rockwell and Julia Kornberg [F]

What it's about: Spanning 2001 to 2034, three Jewish and downwardly mobile siblings come of age in various corners of the world against the backdrop of global crisis.

Who it's for: Fans of Catherine Lacey's Biography of X and Joshua Cohen's The Netanyahus. —SMS

Sand-Catcher by Omar Khalifah, tr. Barbara Romaine [F]

What it is: A suspenseful, dark satire of memory and nation, in which four young Palestinian journalists at a Jordanian newspaper are assigned to interview an elderly witness to the Nakba, the violent 1948 expulsion of native Palestinians from Israel—but to their surprise, the survivor doesn’t want to rehash his trauma for the media.

Who it’s for: Anyone looking insight—tinged with grim humor—into the years leading up to the present political crisis in the Middle East and the decades-long goal of Palestinian autonomy. —NodB

The Shutouts by Gabrielle Korn [F]

What it's about: In the dystopian future, mysteriously connected women fight to survive on the margins of society amid worsening climate collapse.

Who it's for: Fans of Korn's Yours for the Taking, which takes place in the same universe; readers of Becky Chambers and queer-inflected sci-fi. —SMS

What in Me Is Dark by Orlando Reade [NF]

What it's about: The enduring, evolving influence of Milton's Paradise Lost on political history—and particularly on the work of 12 revolutionary readers, including Malcom X and Hannah Arendt.

Who it's for: English majors and fans of Ryan Ruby and Sarah Bakewell—but I repeat myself. —SMS

The Afterlife Is Letting Go by Brandon Shimoda [NF]

What it's about: Shimoda researches the mass incarceration of Japanese Americans during WWII, and speaks with descendants of those imprisoned, for this essay collection about the “afterlife” of cruelty and xenophobia in the U.S.

Who it’s for: Anyone to ever visit a monument, museum, or designated site of hallowed ground where traumatic events have taken place. —NodB

No Place to Bury the Dead by Karina Sainz Borgo, tr. Elizabeth Bryer [F]

What it's about: When Angustias Romero loses both her children while fleeing a mysterious disease in her unnamed Latin American country, she finds herself in a surreal, purgatorial borderland where she's soon caught in a power struggle.

Who it's for: Fans of Maríana Enriquez and Mohsin Hamid. —SMS

The Rest Is Silence by Augusto Monterroso, tr. Aaron Kerner [F]

What it is: The author of some of the shortest, and tightest, stories in Latin American literature goes long with a metafictional skewering of literary criticism in his only novel.

Who it's for: Anyone who prefers the term "palm-of-the-hand stories" to "flash fiction." —JHM

Tali Girls by Siamak Herawi, tr. Sara Khalili [F]

What it is: An intimate, harrowing, and vital look at the lives of girls and women in an Afghan mountain village under Taliban rule, based on true stories.

Who it's for: Readers of Nadia Hashimi, Akwaeke Emezi, and Maria Stepanova. —SMS

Sun City by Tove Jansson, tr. Thomas Teal [F]

What it's about: During her travels through the U.S. in the 1970s, Jansson became interested in the retirement home as a peculiarly American institution—here, she imagines the tightly knit community within one of them.

Who it's for: Fans of Jansson's other fiction for adults, much of which explores the lives of elderly folks; anyone who watched that documentary about The Villages in Florida. —SMS

Editor's note: We're always looking to make our seasonal book previews more useful to the readers, writers, and critics they're meant to serve. Got an idea for how we can improve our coverage? Tell me about it at sophia@themillions.com.

[millions_email]

Memoir as Addiction: On Michelle Tea’s ‘Against Memoir’

Though she has published about as many books of fiction as she has memoir, Michelle Tea is probably best known for writing about her own life. This is due in part to the fact that even some of her fictional characters—in particular, the writer character named Michelle who starred in 2016’s astonishing dystopian novel-memoir hybrid, Black Wave—can be understood as stand-ins for herself. But it’s also certainly the case that the rollicking, hilarious cult of personality that is, in some ways, the engine of Tea’s books has become inseparable from the real person. If an artist is someone who creates their own life, then Tea has done this, then made that life into a further creation by chronicling every aspect of it and casting herself, her friends, and her lovers as larger-than-life, practically heroic figures.

There is something uniquely fascinating about the results of this. Reading Tea’s work, you get the sense that she is painting a large and beautiful but terrifying mural on the wall—all pinks and purples, fairytale turrets and monsters—and when the thing inevitably becomes enchanted, she will walk into it and decide to live there instead. As she writes in this new collection of essays, though, that might not be the healthiest impulse.

As she describes in bits and pieces throughout this book, Tea started her literary career in the ’90s, sitting in San Francisco dive bars, drinking and writing about her love life, then reading the contents of her notebook out loud at open mics around the city. After leaving her hometown of Chelsea, Mass., the gritty little city located across the Mystic River from Boston—and a place that still haunts everything she writes—she made her way to the Bay Area with her queerness, brokeness, and punkiness as her guides. She soon plugged into the city’s underground gay community, finding her first girlfriends and discovering herself as a writer at the same time.

Now a fixture in the San Francisco scene, she runs her own reading series, a nonprofit called RADAR that she founded to promote queer artists with affordable literary programming. (Disclosure: This reviewer once read at a RADAR event and had a lot of fun doing it.) Those of us who love her today love her for her steady stream of fearless, vivid writing about sex and love, working-class family life, bad jobs, city life, sexual abuse, substance abuse, and looking/feeling/being socially unacceptable. Tough-minded and naturally funny, charming and tattooed, Tea became both popular and respected—a bona fide literary figure—simply by writing about herself.

So why is she now, after having made it such an important aspect of her writing life, against memoir? Well, she isn’t, exactly. But as she writes from her now-sober, more settled life, she recognizes it for the dangerous occupation that it is—a betrayal of friendships and confidences, the desire for revenge always slipping around under the surface like a shark. To illustrate this, Tea recounts in Against Memoir’s title essay the time she performed an old story about “the bitch who stole [her] girlfriend” to a packed bar, only to discover that the woman who’d done the stealing years earlier was in the audience—and not for the first time. The other time Tea performed this piece in front of her, the woman went outside and kicked a bus shelter in anger and broke her foot. In the same essay, Tea compares the drive to write memoir to alcoholism—an addiction she has kicked, though she vows never to give up her memoir habit. She also refers to her profession interchangeably as “writing” and the compulsive behavioral condition “hypergraphia,” and it’s not entirely clear whether she’s kidding.

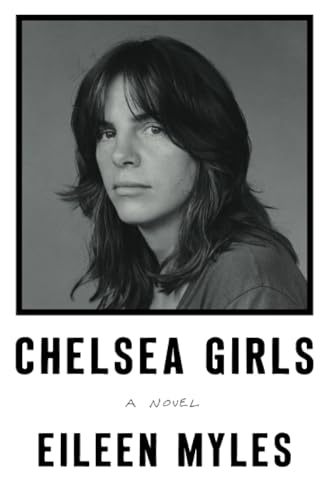

Though this book shows how Tea’s work has developed from straightforward memoir to a more nuanced form of self-reflexive cultural critique, memoir makes up about a third of it. The section “Writing & Life” is composed of the kind of stories she’s best known for: outrageous yarns about things like the Sister Spit reading tours she ran in the ’90s and the lousy part-time jobs she worked one summer as a teenager. But interestingly, her writing about art—the ostensibly critical pieces—are among the strongest in the book. When she writes about Eileen Myles’s lesbian classic, Chelsea Girls, or about Andy Warhol’s would-be killer Valerie Solanas and her SCUM Manifesto with tenderness and understanding, the electricity almost leaps off the page. “The City to a Young Girl,” a complex and affecting piece about the Trump presidency, a poem written by a teenage girl, and Tea’s own girlhood, is probably the apotheosis of Tea’s development as a nonfiction writer.

Of course, writing about other people and their ideas can be a powerful way of writing about yourself. With the long-form essay “HAGS in Your Face,” Tea gives us good old-fashioned journalism, reporting on the gang of hard-living gutter-punk women who called themselves the HAGS and were notorious to San Francisco’s larger gay community during the ’90s. Tea interviews several of the HAGS who fascinated her back then, and they tell her how they traveled in packs, scooping each other up from the “black hole” of “addiction, homophobia, family abandonment, gender discrimination, all of it.” With her portrait of the HAGS, she shows us how being forced to the fringes of society can damage people irreparably just as it can forge them into something beautiful and brand-new.

[millions_ad]

When Tea seems less sure of herself, she can lean too heavily on a tossed-off charm to gloss over her discomfort, like when she worries aloud that her “hetero sisters are not getting the most out of their vaginas.” But on the whole, this book, like all of her best writing, bristles with life and a fierce intellect. Her voice is as distinct as ever, and her ability to conjure something—an album cover, the feeling of a hangover—in just a few phrases, like Zorro (zip, zip, zip!) is still wonderfully intact.

The most delightful discovery—to me, anyway—is a version of a short, bright piece called “Pigeon Manifesto” that I have only ever seen in print as a Poems-for-All book the size and shape of a matchbook, put out in 2004 (the book credits it as a performance Tea gave in San Francisco that same year). Writing about herself and her fellow misfits as much as the maligned city birds, Tea says: “When you say to me, ‘I hate pigeons,’ I want to ask you who else do you hate. It makes me suspicious. …Pigeons…are chameleons, grey as the concrete they troll for scraps, at night they huddle and sing like cats. Their necks are glistening, iridescent as an oil-slick rainbow, they mate for life, and they fly.”

You Can’t Go Wrong With Heart: The Millions Interviews Jami Attenberg

I'd been hearing about Jami Attenberg's latest novel, All Grown Up, long before it went on sale. Early readers loved it, and their praise produced a kind of roar across the Internet, one full of joy and ferocity. People were grateful for this story and this character: Andrea Bern, a single woman who doesn't have kids, and doesn't want them. When I finally got my hands on a copy, I saw what everyone was talking about; Andrea is like so many women I know, and yet, she is unlike most female characters in fiction. She is also more than her demographic (as we all are). Through a series of droll but big-hearted and compassionate vignettes, Attenberg depicts a profound and authentic portrait of a woman as she moves through this beautiful yet often unjust world. In All Grown Up, there is joy, loneliness, pleasure, despair, grief, hope, frivolity, and matters of great import.

Jami Attenberg is The New York Times bestselling author of five other books, including The Middlesteins and Saint Mazie. She was kind enough to answer my questions via email.

The Millions: All Grown Up is told in a series of vignettes about Andrea's life -- there's one terrific, pithy chapter early on, for instance, called, simply, "Andrea," about how everyone keeps recommending the same book about being single. There are a few chapters about Andrea's friend Indigo: in one she gets married, in another she has child, and so on. Some are about Andrea's dating life, and others focus on her family. I'm curious about how working within this structure affected your understanding of Andrea herself, seeing as she comes into focus story by story, but not in a traditional, chronological way. I also wonder what you want the reader to feel, seeing her from these various angles, some of which overlap, while others don't.

Jami Attenberg: I made a list -- I wish I could find it now; it’s in a notebook somewhere -- of all these different parts of being an adult. For example: your relationship with your family, your career, your living situation, etc. And then I created story cycles around them, and often they were spread out over decades. As an example: what Andrea’s apartment was like when she was growing up versus how she felt about her apartment as an adult in her late 20s versus her late 30s, and how those memories informed her feelings of safety and security and space. A sense of home is a universal topic. And then eventually more relevant, nuanced parts of a specifically female adulthood emerged as I wrote, and little cycles formed around those subjects. So the writing of this book in terms of structure was really an accrual of these cycles.

The goal was to tell the whole truth about this character, and why she had become the person she was -- the adult she was, I guess -- so that she could understand it/herself, and move on from it. The fact that it’s not linear is true to the story of our lives. The moments that inform our personalities come at us at different times. If you were to make a “What Makes Me the Way I Am” top 10 list in order of importance, there’s no way it would be in chronological order. And to me they’re all connected. I’d hope readers see some of their own life challenges in her, and if not her, in some of the other characters, even if they happen at different times. Everything keeps looping around again anyway. (We can’t escape our pasts, we are doomed to repeat ourselves, we are our parents, etc.)

TM: In my mind, and likely in the minds of others, you lead an ideal "writer's life" -- you're pretty prolific, for one, and you also don't teach. You now live in two places: New Orleans and New York City -- which seems chic and badass to me. Plus you have a dog with the perfect under bite! Can you talk a little about your day-to-day life as an artist, and what you think it's taken (besides, say, the stars aligning), to get there? Any advice for writers who want to be like you when they're all grown up?

JA: It took me a long time to figure out what would make me happy, and this existence seems to be it, for a while anyway. I’m 45 now, and I started planning for this life a few years ago, but before then I had no vision except to keep writing, and that was going to be enough for me. Then, after my third winter stay in New Orleans, I realized I had truly fallen in love with the city. And then I had a dream, an actual adult goal. I had two cities I loved, and I wanted to be in both. So it has meant a lot to me to get to this place. I worked so hard to get here! I continue to work hard. No one hands it to you, I can tell you that much, unless you are born rich, which I was not, and even then that’s just money, it’s not exactly a career. And I think the career part, the getting to write and be published and be read part, is the most gratifying of all. Unless success is earned it is not success at all.

My day-to-day life is wake, read, drink coffee, walk the dog, say hi to my neighbors, come home, be extremely quiet for hours, write, read, look at the Internet, eat, walk the dog, have a drink, freak out about the state of America, and have some dinner, maybe with friends. Soon I’ll be on tour for two months, and that will be a whole different way of living, though still part of my professional life. But when I am writing, it is a quiet and simple existence in which I take my work seriously. I have no advice at all to anyone except to keep working as hard as you possibly can.

TM: I've always loved the sensuality of your writing. Whether the prose is describing eating, or having sex, or simply the varied textures of life in New York City, we are with your characters, inside their bodies. What is the process for you, in terms of inhabiting a character's physical experience? Does it happen on the sentence level, or as you enter the fictive dream, or what?

JA: Well thank you, Edan. I’m a former poet, for starters, so I’m always looking to up the language in a specific kind of way. I certainly close my eyes and try to be in the room with a character, and inside their flesh as well, I suppose. I write things to turn myself on. Even my bad sex scenes are in a strange way arousing to me, even if it’s just because they make me laugh. It’s all playtime for me.

All of this kind of thinking comes in the early stages but also in my final edits of the second draft. Most of the lyricism of the work is done before I send the book out to my editor. Her notes to me address the nuts and bolts of plot and architecture, and often also emotions and character motivation. But the language, for the most part, she leaves to me.

TM: My favorite relationship in the novel is between Andrea and her mother. It's loving and comforting even though there are also real tensions and conflicts between them. Can you talk about creating a nuanced, and thus realistic, portrayal of mother and daughter?

JA: It is also my favorite relationship! I could write the two of them forever. I am satisfied with the book as it stands but would still love to write a chapter where the two of them go to the Women’s March together, and Andrea’s mother knits her a pussy hat and Andrea doesn’t want to wear it because she only ever wears black. I have pages and pages of dialogue between them that I never used but wrote anyway just because they were fun together, or fun for me the author, but maybe not fun between the two of them.

Their relationship really comes from living in New York City for 18 years and watching New York mothers and daughters together out in the world and just channeling that. These characters are very much a product of eavesdropping. I try to approach these kinds of family relationships like this: everyone is always wrong and everyone is always right. Like their patterns and emotions are already so ingrained that there’s no way out of it except through, because no one will ever win. But also there is love. Always there is love. And that’s how I know they’ll make it to the other side.

TM: This novel has so many terrific female characters, who are at once immediately recognizable (sort of like tropes of contemporary womanhood, if that makes sense) and also unique. Aside from Andrea and her mother, there is Andrea's sister-in-law, Greta, a once elegant and willowy magazine editor who is depleted (spiritually and otherwise) by her child's illness; Indigo, ethereal yoga teacher turned rich wife and mother, and then divorcée and single mother; the actress with the great shoes who moves into Andrea's building; Andrea's younger and (seemingly?) self-possessed coworker Nina. They're all magnetic -- and they also all fail to hold onto that magnetism. Their cool grace, at least in Andrea's eyes, is tarnished, often by the burdens of life itself. Did you set out to have these women orbiting Andrea, contrasting her, sometimes echoing her, or was there another motivation in mind?

JA: These women were all there from the beginning -- all of them. I had to grow them and inform them, but there were no surprise appearances. I never thought -- oh where did she come from? They were all just real women living and working in today’s New York City, and also they were real women who lived inside of me. I needed each of these women to be in the book or it wouldn’t have been complete. And also I certainly needed them to question Andrea. For example, her sister-in-law in particular sometimes acts as a stand-in for what I imagine the reader must be thinking, while her mother acts as a stand-in for me, both of them interrogating Andrea at various times.

And also always, always, always in my work the female characters are going to be the most interesting. Most of the chapters are named after women. I had no doubt in my mind that I wanted a collective female energy to buoy this book. We’re always steering the fucking ship, whether it’s acknowledged or not.

TM: Were there any models for this book in terms of voice, structure, tone of subject? Are there, in general, any authors and novels that are "fairy godmothers" for you and your writing?

JA: Each book is different, I have a different reading list, but Grace Paley is my mothership no matter what, because of her originality, grasp of voice and dialect, and incredible heart and compassion.

As I began writing All Grown Up, I was reading Patti Smith’s M Train and Maggie Nelson’s The Argonauts, and when I was halfway done with the book I started reading Eileen Myles’s Chelsea Girls. I was not terribly interested in fiction for the most part. I wanted this book to feel memoiristic -- not like an actual memoir, that one writes and tries to put in neat little box, perfect essays or chapters, but just genuinely like this woman was telling you every single goddamn, messy thing you needed to know about her life.

Those three books all feel like unique takes on the memoir. Patti Smith just talks about whatever the fuck she wants to talk about, and Maggie Nelson writes in those short, meticulous, highly structured bursts, where you genuinely feel like she is making her case, and in Chelsea Girls Eileen has this dreamy, meandering quality, although she knows exactly what she’s doing, she’s scooping you up and putting you in her pocket and taking you with her wherever she wants to go. So all of those books somehow connected together for me while I was establishing the feel of this book.

And when I was finishing I read Naomi Jackson’s gorgeous debut, The Star Side of Bird Hill, which is also about family and a collection of strong women and coming of age, although the people growing up in her book are much younger than my narrator. But it was just stunning, and it made me cry, and the emotions felt so real and true. So I think reading her was an excellent inspiration as I wrote those final pages. Like you can’t go wrong with heart.

TM: Since is The Millions, I must ask you: What was the last great book you read?

JA: I just judged the Pen/Bingham contest and all of the books on our shortlist were wonderful: Insurrections by Rion Amilcar Scott; We Show What We Have Learned by Clare Beams; The Mothers by Brit Bennett; Homegoing by Yaa Gyasi, and Hurt People by Cote Smith.

Year in Reading Outro

Year in Reading reminds me of that cinematic device where the camera slowly backs away from the characters we’ve been following until it’s looking at them from outside their window, and then back farther still until you see into their neighbors’ windows as well, and farther still to show a whole building of occupied windows, and then a whole city, until you are looking at hundreds of little scenes in hundreds of little windows. And you think, if I contain multitudes, and there are multitudes of people, then there are multitudes upon multitudes, and your brain starts to spin. What I’m trying to say is that over the last few weeks, 78 writers have written about close to 500 books, and following the posts as they roll out is as intimidating and overwhelming one day as it is invigorating the next.

Of those books, nearly half were fiction, the most popular genre by far, followed by biography and memoir, making up roughly 15% of the recommendations. Another 15% was taken up by traditional non-fiction — books I categorized as either “history,” “essays,” or “events.” And our contributors recommended 55 books of poetry during the series, a healthy list for anyone who is definitely, no take-backs, going to read more poetry in 2016.

Surprising no one, Ta-Nehisi’s Coates’s Between the World and Me and Elena Ferrante’s Neapolitan Quartet were the twin titans of this year’s series, each being cited by 12 of our contributors. Close behind, A Little Life and The Argonauts were each mentioned eight times. What is surprising, and a little delightful, is that two contributors read Colette’s Claudine at School this year, and two more read Chelsea Girls by Eileen Myles. I’ve added Eileen Myles to my reading list for next year based on that, and because Chelsea Girls wasn’t even her only book to be recommended this year. I’ve also added Joy Harjo’s Conflict Resolution for Holy Beings based on Sandra Cisneros’s recommendation, and the line she quoted, and its awesome title. I also added Vivian Gornick, especially The Odd Woman and the City, because Hannah says it’s “about what it feels like to be lonely, and what it feels like to be free. It’s about what it feels like to change your mind, about the intellectual, spiritual, and emotional growth that comes after you’ve come of age, and even after you’ve ‘come into your own.’”

It’s been a privilege for Lydia and I to edit the series this year. We hope you’ve found a few things you’d like to read, a few writers who share your tastes, and a few who don’t. Year in Reading is like drinking from a firehose of literary wonders. It always helps me start off my new year itching to get into the books I’ll write about at the end of it. See you then.

More from A Year in Reading 2015

Don't miss: A Year in Reading 2014, 2013, 2012, 2011, 2010, 2009, 2008, 2007, 2006, 2005

The good stuff: The Millions' Notable articles

The motherlode: The Millions' Books and Reviews

Like what you see? Learn about 5 insanely easy ways to Support The Millions, and follow The Millions on Twitter, Facebook, Tumblr.

A Year in Reading: Maggie Nelson

I was captivated this past reading year by a trio of books about, among other things, hard living: Straight Life by Art and Laurie Pepper, Chelsea Girls by Eileen Myles, and Like Being Killed by Ellen Miller. Myles’s Chelsea Girls meant everything to me when it came out in 1994, so it took me by surprise, in reading it anew (it was re-released by Ecco this past year) to find it even better than I remembered, a true miracle. Re-subtitled "a novel," it is a work of kinetic, ecstatic, muscular, hilarious, sorrowful, valiant, original, necessary, and timeless genius. Straight Life (also from 1994) and Like Being Killed (1998) were new revelations. Straight Life, which is the 500-page, dope-soaked story of jazz musician Art Pepper, is a fascinating and repugnant read, made all the more so by the backstory of how the book came into being (it’s largely an oral history told to his wife Laurie -- see “The Tale of the Tape: The Miracle of Straight Life” in the September 2014 issue of Harper’s, for more on that story). The novel Like Being Killed is also a junkie’s tale, along with a story of friendship, the Lower East Side, Jewishness, AIDS, the fraughtness of being fat, being female, and more. I was so taken with its erudition, abjection, and opulence that I immediately looked for anything else Miller had written, and was crestfallen to discover that she’d died in 2008 at age 41, leaving this novel her only offering. It’s out of print, which is a howling pity -- but so was Myles’s Chelsea Girls, until this year. Hope springs eternal.

More from A Year in Reading 2015

Don't miss: A Year in Reading 2014, 2013, 2012, 2011, 2010, 2009, 2008, 2007, 2006, 2005

The good stuff: The Millions' Notable articles

The motherlode: The Millions' Books and Reviews

Like what you see? Learn about 5 insanely easy ways to Support The Millions, and follow The Millions on Twitter, Facebook, Tumblr.

Bold and Messy

Over at Full Stop, Josephine Livingstone writes about Eileen Myles’s hip image and the renewed success of Chelsea Girls. Also check out Stephanie LaCava’s Millions essay on how social media helped to push Myles’s book into the mainstream.

A Year in Reading: Sady Doyle

I spent a lot of this year writing a book, making me acutely aware of how terrifying it is to publish one of those things. You can spend years working on a book, and people can just not read it! How many books have I just not read, in my lifetime? What a travesty.

So here’s where I mention two books written by my feminist colleagues, Asking for It by Kate Harding, and Notorious RBG, by Irin Carmon and Shana Knizhnik, and tell you that they are great: Respectively, the Rape Culture 101 breakdown and pop-friendly biography of Ruth Bader Ginsburg you always needed. Reading Feminist Books is good for the soul. Try it.

That said, much of my reading was about feminists of ages past. John Szwed’s Billie Holiday: The Musician and the Myth, published in time for Holiday’s centennial, was fascinating; Holiday’s complicated relationship with her own media coverage and her highly entertaining fights with her publisher over her autobiography Lady Sings the Blues are in there, but more importantly, there’s scads of information about the music. Did you know that, due to illness during her final recording, Billie Holiday was one of the first musicians to use pitch correction? (She sang to a slowed-down backing track and they sped it up to make her voice higher.) Did you know that some of her experiments with tempo were unprecedented in Western music outside of Frédéric Chopin? You do now.

Outside of this, I mostly read for escape. Many titles are too embarrassing to mention, but lots of fantasy and sci-fi paperbacks got dragged out from storage. (Coincidentally: Joan D. Vinge’s out-of-print feminist sci-fi classic The Snow Queen was reprinted this October. And I know this. For totally unspecified reasons.) One 2015 book, however, I’d recommend even to non-nerds: Wylding Hall, by Elizabeth Hand, in which a British psychedelic folk band of the '60s may or may not be hunted down by the Ancient Faerie Spirits of Olde Britain they can’t stop singing about. It’s so scary that I was afraid to walk alone at night afterward, and taps into all Hand’s strengths as a writer: Her stylish prose, her obsessively detailed portraits of musical subcultures, and the witchy, chthonic undercurrents of her '90s classic Waking the Moon, in which (and I’m trying not to spoil anything) a tousle-haired, ethereal icon of Goddess feminism gets possessed by a bloodthirsty Moon Goddess and only a queer folk-punk icon named “Annie” can stop her.

I mean. You read that, right? There’s a book, available in stores, in which Tori Amos and Ani DiFranco battle to the death. You could be reading that, right now. What is stopping you?

Meanwhile, Eileen Myles’s Chelsea Girls, which I’ve been trying to find for years due to a recommendation from Michelle Tea, is being re-issued. And Michelle Tea has a new book, How to Grow Up. This probably also falls under “escapism,” because Eileen Myles and Michelle Tea are both very cool, and I am the sort of person who gets excited about a Snow Queen re-printing.

So: I read these books. You should read these books. You should read all books. I’m just saying: It took someone years to write them. So if you don’t, you’re probably a bad person. No pressure.

More from A Year in Reading 2015

Don't miss: A Year in Reading 2014, 2013, 2012, 2011, 2010, 2009, 2008, 2007, 2006, 2005

The good stuff: The Millions' Notable articles

The motherlode: The Millions' Books and Reviews

Like what you see? Learn about 5 insanely easy ways to Support The Millions, and follow The Millions on Twitter, Facebook, Tumblr.

Bold but Messy: On Eileen Myles and the Fugitive Form

I have an almost full collection of Hanuman Books, the thumb-size editions handmade by the press founded in 1986 by Raymond Foye and Francesco Clemente. They are kept in a glass box and were a gift to my husband. He hasn’t looked at one yet. I can’t stop thinking about them. It was the acid covers with gold leaf titles that initially attracted me to the set; they looked so charming piled together. I am neither art critic nor expert, but I am curious and was drawn to further inquiry. I guess saying they were a present was the best cover for smuggling them into my house. I fell in love with the tightly edited cast of avant-garde works and hard-to-find translations. Here were Henri Michaux and Dodie Bellamy and Bob Flanagan and Eileen Myles and other writers and artists that created works that can be difficult to categorize by genre or media. Foye and Clemente had successfully created objects that were cult and cool and brave and lasting.

I wasn’t completely surprised to hear that this September, HarperCollins will be publishing Myles’s Chelsea Girls. It was Myles, herself, who told me that Chelsea Girls was, at first, “something stapled” and published by John Martin’s Black Sparrow Press, perhaps best known for introducing Charles Bukowski. I love the romance of this, and of an East Village poet and writer whom people say is about to have a moment; an overnight success after 40 years.

Chelsea Girls is an example of a hybrid work that’s taken on cult status. It’s considered an autobiographical novel, straddling the space between nonfiction and fiction. One of the times I meet up with Myles, she is just back from a panel at AWP, the big writers’ conference, with Maggie Nelson, Eula Bliss, and Leslie Jamison, among others, at which she turned to them and said, “Isn’t it a fugitive form you guys are creating?” Well said.

Myles notes that, like her, many of these writers of fugitive form are also poets. And it is social media that, unsurprisingly, has helped to push this once avant-garde approach into the mainstream. She talks about the fluidity of Twitter and Instagram (she’s active on both), the flow of images and captions, and what’s real and what’s not -- considering our intention to portray something altogether different than one’s reality, only the best parts.

“Can we acknowledge part of it (hybrid works) is happening because of social media and engagement with the photograph and film?” Myles sees prose writing in these forms as a natural response to the inundation of images and accompanying words on social media. “The word ‘literary’ is out the window because of all these new forms; the original of the book is no longer the book! It’s not a collective intelligence, it’s a collecting intelligence!” She cites Bellamy, Kathy Acker, Chris Kraus and even Violette le Duc as examples of writers who have long trafficked in this fluid space. From here, there’s the aforementioned panelists, and others like Sheila Heti and Miranda July. Maybe fugitive form is the new intermedia?

In a 1965 essay, “Synthesthesia and Intersense: Intermedia,” early Fluxus artist and publisher Dick Higgins offers the term “intermedia” taken from the writings of Samuel Taylor Coleridge in 1812. He writes, “We are approaching the dawn of a classless society, to which separation into rigid categories is absolutely irrelevant.” He mentions Marcel Duchamp as an early adopter of this play with his readymades, and further examples range from John Cage’s “music and philosophy” to Robert Rauschenberg’s “combines” or Allan Kaprow and Al Hansen’s “Happenings.”

In 1981, Higgins wrote a follow-up essay explaining that his intention was “to offer a means of ingress into works,” to abate fear of new forms, to not be “dismissed as avant-garde: for specialists only.” He was worried that he may have overvalued the term, in his efforts to “popularize” avant-garde intermedia. It is a thoughtful meditation that is as important today as then, but for different reasons. Higgins established Something Else Press in 1964 (-1974) and it was in his first newsletter that he would publish “Synthesthesia and Intersense,” arguing: “It seemed foolish simply to publish my little essay in some existing magazine, where it could be shelved or forgotten.” Today it could have appeared and lived on a website like this one.

Something Else Press intrigues me, much in the same way as Hanuman Books. It sought to create objects with an emphasis on decimating the avant-garde in a pre-Internet world. I reached out to Higgins’s daughter with fellow Fluxus artist Alison Knowles. Hannah Higgins is a professor of art history at the University of Illinois Chicago.

She told me an interesting anecdote about her father attending boarding school in Vermont and becoming friends with Andre Breton’s daughter Aube, who had been sent there when her parents left France. “I think that’s fundamentally when Dick became Dick,” Hannah says of imagining him “being entertained with stories of the French avant-garde.”

When Dick went to Alison and told her he was starting a press, he said he was going to give it a Marxist-friendly title, Shirtsleeves, as in rolling up your sleeves. Call it “something else,” she said. And it was decided.

Dick would go on to publish A Primer of Happenings & Time/Space Art, Al Hansen's book about performance art, and to publish the likes of Emmet Williams’s “machine driven schema” computer poetry and the last work ever published by Duchamp. It was Knowles who was very close to Duchamp. (“John Cage introduced me to Marcel so we could do the print Coeur Volants together. Which we did,” she writes me.) It is noteworthy that Dick was in Cage’s composition class at the New School for Social Research, as was Hansen.

I corresponded with Bibbe Hansen, Al’s daughter, Andy Warhol-intimate, and, interestingly, the musician Beck’s mother. Of Something Else Press, which, of course, published her father, Hansen says, “The work was so little regarded or championed in its time, I think Something Else Press perhaps helped to archive these works until history and culture were able to catch up,” she says. "These valiant Davids played a vital and important role in a world of publishing Goliaths disinterested in anything untried or new.”

And here’s where I start to worry. I am worried that it’s not the innovators or early adopters that are getting play in publications where one needs to be vetted by a select few before being promoted by them. This leads me to consider the concessions and compromises being made even by these publications in an effort to garner “hits” and gain “followers.” Characters that were once forbidden now appear on covers. And we are turned upside down, because it’s suddenly not the hard work that’s being promoted, but something else altogether. We allow certain names to guest edit publications in an effort to get readers; we are taken with the commodity of youth culture. And all for good reason. I don’t condemn any of this, rather ask for a kind of awareness through the perspective of the '60s era avant-garde, small presses, friendships, and networks. And I agree with Myles that there has to be a kind of authenticity to the collective intelligence, simply because it is so.

I ask Bibbe Hansen how she imagines social media would play out were it around while she was growing up: “Well, Andy would have LOVED it! HE would have been KING of Tweets!” She’s one of the few people with the credibility to say this.

“The avant-garde was always a game of friends,” Hannah says. “If you actually look at what’s driving those texts it's intimate, small meetings, people, and one-to-one encounters. You hear from artists all the time that they can’t be friends with someone whose work they really hate, so you’ll tend to get social networks that are affinity networks, as well. It wasn’t just that Dick was publishing his friend and lovers, but that he could love them deeply if he really respected and admired their work.”

Hannah says,“But if the work is even to become truly important to large numbers of people, it will be because the new medium allows for greater significance, not simply because it's formal nature assures it of relevance.” She explains Dick’s emphasis -- that it wasn’t about social or geographic “climbing” to the latest, greatest big name, rather creating a “place” where people, friend, children, other artists, are affected by the work.

When I first met Myles and we talked about her experience with Hanuman Books, she also told me that these publications were driven by “intimate encounters,” meaning networks and relationships among artists. “These small presses have been the microphone for groundbreaking work.”

Myles believes that friendship and love have to be the reason you publish books. She prescribes publishers to “learn to represent, and not gamble,” which seems to me just right.

But then, how to push aside worrying about the other, louder, bigger voices. Myles tells me her take on a “celebrity” with over 20 million followers: “The essential fact that there’s something wrong, but something right. Think about it,” she says. “I love that it’s messy.”

So, what’s one to do?

“Find a messy team and write for them.”

Play the game, but do the work.

And now, Myles is about to have a “moment.” Only, she’s been living this moment her whole adult life, and as Chelsea Girls tells it, even before.