Mentioned in:

A Year in Reading: 2024

Welcome to the 20th (!) installment of The Millions' annual Year in Reading series, which gathers together some of today's most exciting writers and thinkers to share the books that shaped their year. YIR is not a collection of yearend best-of lists; think of it, perhaps, as an assemblage of annotated bibliographies. We've invited contributors to reflect on the books they read this year—an intentionally vague prompt—and encouraged them to approach the assignment however they choose.

In writing about our reading lives, as YIR contributors are asked to do, we inevitably write about our personal lives, our inner lives. This year, a number of contributors read their way through profound grief and serious illness, through new parenthood and cross-country moves. Some found escape in frothy romances, mooring in works of theology, comfort in ancient epic poetry. More than one turned to the wisdom of Ursula K. Le Guin. Many describe a book finding them just when they needed it.

Interpretations of the assignment were wonderfully varied. One contributor, a music critic, considered the musical analogs to the books she read, while another mapped her reads from this year onto constellations. Most people's reading was guided purely by pleasure, or else a desire to better understand events unfolding in their lives or larger the world. Yet others centered their reading around a certain sense of duty: this year one contributor committed to finishing the six Philip Roth novels he had yet to read, an undertaking that he likens to “eating a six-pack of paper towels.” (Lucky for us, he included in his essay his final ranking of Roth's oeuvre.)

The books that populate these essays range widely, though the most commonly noted title this year was Tony Tulathimutte’s story collection Rejection. The work of newly minted National Book Award winner Percival Everett, particularly his acclaimed novel James, was also widely read and written about. And as the genocide of Palestinians in Gaza enters its second year, many contributors sought out Isabella Hammad’s searing, clear-eyed essay Recognizing the Stranger.

Like so many endeavors in our chronically under-resourced literary community, Year in Reading is a labor of love. The Millions is a one-person editorial operation (with an invaluable assist from SEO maven Dani Fishman), and producing YIR—and witnessing the joy it brings contributors and readers alike—has been the highlight of my tenure as editor. I’m profoundly grateful for the generosity of this year’s contributors, whose names and entries will be revealed below over the next three weeks, concluding on Wednesday, December 18. Be sure to subscribe to The Millions’ free newsletter to get the week’s entries sent straight to your inbox each Friday.

—Sophia Stewart, editor

Becca Rothfeld, author of All Things Are Too Small

Carvell Wallace, author of Another Word for Love

Charlotte Shane, author of An Honest Woman

Brianna Di Monda, writer and editor

Nell Irvin Painter, author of I Just Keep Talking

Carrie Courogen, author of Miss May Does Not Exist

Ayşegül Savaş, author of The Anthropologists

Zachary Issenberg, writer

Tony Tulathimutte, author of Rejection

Ann Powers, author of Traveling: On the Path of Joni Mitchell

Lidia Yuknavitch, author of Reading the Waves

Nicholas Russell, writer and critic

Daniel Saldaña París, author of Planes Flying Over a Monster

Lili Anolik, author of Didion and Babitz

Deborah Ghim, editor

Emily Witt, author of Health and Safety

Nathan Thrall, author of A Day in the Life of Abed Salama

Lena Moses-Schmitt, author of True Mistakes

Jeremy Gordon, author of See Friendship

John Lee Clark, author of Touch the Future

Ellen Wayland-Smith, author of The Science of Last Things

Edwin Frank, publisher and author of Stranger Than Fiction

Sophia Stewart, editor of The Millions

A Year in Reading Archives: 2023, 2022, 2021, 2020, 2019, 2018, 2017, 2016, 2015, 2014, 2013, 2011, 2010, 2009, 2008, 2007, 2006, 2005

The Great Fall 2024 Book Preview

With the arrival of autumn comes a deluge of great books. Here you'll find a sampling of new and forthcoming titles that caught our eye here at The Millions, and that we think might catch yours, too. Some we’ve already perused in galley form; others we’re eager to devour based on their authors, plots, or subject matters. We hope your next fall read is among them.

—Sophia Stewart, editor

October

Season of the Swamp by Yuri Herrera, tr. Lisa Dillman [F]

What it is: An epic, speculative account of the 18 months that Benito Juárez spent in New Orleans in 1853-54, years before he became the first and only Indigenous president of Mexico.

Who it's for: Fans of speculative history; readers who appreciate the magic that swirls around any novel set in New Orleans. —Claire Kirch

The Black Utopians by Aaron Robertson [NF]

What it is: An exploration of Black Americans' pursuit and visions of utopia—both ideological and physical—that spans the Reconstruction era to the present day and combines history, memoir, and reportage.

Who it's for: Fans of Saidiya Hartman's Wayward Lives, Beautiful Experiments and Kristen R. Ghodsee's Everyday Utopia. —Sophia M. Stewart

The Third Realm by Karl Ove Knausgaard, tr. Martin Aitken [F]

What it is: The third installment in Knausgaard's Morning Star series, centered on the appearance of a mysterious new star in the skies above Norway.

Who it's for: Real Knausgaard heads only—The Wolves of Eternity and Morning Star are required reading for this one. —SMS

Brown Women Have Everything by Sayantani Dasgupta [NF]

What it is: Essays on the contradictions and complexities of life as an Indian woman in America, probing everything from hair to family to the joys of travel.

Who it's for: Readers of Durga Chew-Bose, Erika L. Sánchez, and Tajja Isen. —SMS

The Plot Against Native America by Bill Vaughn [F]

What it is: The first narrative history of Native American boarding schools— which aimed "civilize" Indigenous children by violently severing them from their culture— and their enduring, horrifying legacy.

Who it's for: Readers of Ned Blackhawk and Kathleen DuVal. —SMS

The Mighty Red by Louise Erdrich [F]

What it is: Erdrich's latest novel set in North Dakota's Red River Valley is a tale of the intertwined lives of ordinary people striving to survive and even thrive in their rural community, despite environmental upheavals, the 2008 financial crisis, and other obstacles.

Who it's for: Readers of cli-fi; fans of Linda LeGarde Grover and William Faulkner. —CK

The Position of Spoons by Deborah Levy [NF]

What it is: The second book from Levy in as many years, diverging from a recent streak of surrealist fiction with a collection of essays marked by exceptional observance and style.

Who it's for: Close lookers and the perennially curious. —John H. Maher

The Bog Wife by Kay Chronister [F]

What it's about: The Haddesley family has lived on the same West Virginia bog for centuries, making a supernatural bargain with the land—a generational blood sacrifice—in order to do so—until an uncovered secret changes everything.

Who it's for: Readers of Karen Russell and Jeff VanderMeer; anyone who has ever used the phrase "girl moss." —SMS

The Great When by Alan Moore [F]

What it's about: When an 18-year old book reseller comes across a copy of a book that shouldn’t exist, it threatens to upend not just an already post-war-torn London, but reality as we know it.

Who it's for: Anyone looking for a Sherlock Holmes-style mystery dipped in thaumaturgical psychedelia. —Daniella Fishman

The Message by Ta-Nehisi Coates [NF]

What it's about: One of our sharpest critical thinkers on social justice returns to nonfiction, nearly a decade after Between the World and Me, visiting Dakar, to contemplate enslavement and the Middle Passage; Columbia, S.C., as a backdrop for his thoughts on Jim Crow and book bans; and the Israeli-occupied West Bank, where he sees contemporary segregation in the treatment of Palestinians.

Who it’s for: Fans of James Baldwin, George Orwell, and Angela Y. Davis; readers of Nikole Hannah-Jones’s The 1619 Project and Isabel Wilkerson’s Caste, to name just a few engagements with national and racial identity. —Nathalie op de Beeck

Abortion by Jessica Valenti [NF]

What it is: Columnist and memoirist Valenti, who tracks pro-choice advocacy and attacks on the right to choose in her Substack, channels feminist rage into a guide for freedom of choice advocacy.

Who it’s for: Readers of Robin Marty’s The New Handbook for a Post-Roe America, #ShoutYourAbortion proponents, and followers of Jennifer Baumgartner’s [I Had an Abortion] project. —NodB

Gifted by Suzuki Suzumi, tr. Allison Markin Powell [F]

What it's about: A young sex worker in Tokyo's red-light district muses on her life and recounts her abusive mother's final days, in what is Suzuki's first novel to be translated into English.

Who it's for: Readers of Susan Boyt and Mieko Kanai; fans of moody, introspective fiction; anyone with a fraught relationship to their mother. —SMS

Childish Literature by Alejandro Zambra, tr. Megan McDowell [F]

What it is: A wide-ranging collection of stories, essays, and poems that explore childhood, fatherhood, and family.

Who it's for: Fans of dad lit (see: Lucas Mann's Attachments, Keith Gessen's Raising Raffi, Karl Ove Knausgaard's seasons quartet, et al). —SMS

Books Are Made Out of Books ed. Michael Lynn Crews [NF]

What it is: A mining of the archives of the late Cormac McCarthy with a focus on the famously tight-lipped author's literary influences.

Who it's for: Anyone whose commonplace book contains the words "arquebus," "cordillera," or "vinegaroon." —JHM

Slaveroad by John Edgar Wideman [F]

What it is: A blend of memoir, fiction, and history that charts the "slaveroad" that runs through American history, spanning the Atlantic slave trade to the criminal justice system, from the celebrated author of Brothers and Keepers.

Who it's for: Fans of Clint Smith and Ta-Nehisi Coates. —SMS

Linguaphile by Julie Sedivy [NF]

What it's about: Linguist Sedivy reflects on a life spent loving language—its beauty, its mystery, and the essential role it plays in human existence.

Who it's for: Amateur (or professional) linguists; fans of the podcast A Way with Words (me). —SMS

An Image of My Name Enters America by Lucy Ives [NF]

What it is: A collection of interrelated essays that connect moments from Ives's life to larger questions of history, identity, and national fantasy,

Who it's for: Fans of Ives, one of our weirdest and most wondrous living writers—duh; anyone with a passing interest in My Little Pony, Cold War–era musicals, or The Three Body Problem, all of which are mined here for great effect. —SMS

Women's Hotel by Daniel Lavery [F]

What it is: A novel set in 1960s New York City, about the adventures of the residents of a hotel providing housing for young women that is very much evocative of the real-life legendary Barbizon Hotel.

Who it's for: Readers of Mary McCarthy's The Group and Rona Jaffe's The Best of Everything. —CK

The World in Books by Kenneth C. Davis [NF]

What it is: A guide to 52 of the most influential works of nonfiction ever published, spanning works from Plato to Ida B. Wells, bell hooks to Barbara Ehrenreich, and Sun Tzu to Joan Didion.

Who it's for: Lovers of nonfiction looking to cover their canonical bases. —SMS

Blue Light Hours by Bruna Dantas Lobato [F]

What it's about: Through the emanating blue-glow of their computer screens, a mother and daughter, four-thousand miles apart, find solace and loneliness in their nightly Skype chats in this heartstring-pulling debut.

Who it's for: Someone who needs to be reminded to CALL YOUR MOTHER! —DF

Riding Like the Wind by Iris Jamahl Dunkle [NF]

What it is: The biography of Sanora Babb, a contemporary of John Steinbeck's whose field notes and interviews with Dust Bowl migrants Steinbeck relied upon to write The Grapes of Wrath.

Who it's for: Steinbeck fans and haters alike; readers of Kristin Hannah's The Four Winds and the New York Times Overlooked column; anyone interested in learning more about the Dust Bowl migrants who fled to California hoping for a better life. —CK

Innie Shadows by Olivia M. Coetzee [F]

What it is: a work of crime fiction set on the outskirts of Cape Town, where a community marred by violence seeks justice and connection; also the first novel to be translated from Kaaps, a dialect of Afrikaans that was until recently only a spoken language.

Who it's for: fans of sprawling, socioeconomically-attuned crime dramas a la The Wire. —SMS

Dorothy Parker in Hollywood by Gail Crowther [NF]

What it is: A history of the famous wit—and famous New Yorker—in her L.A. era, post–Algonquin Round Table and mid–Red Scare.

Who it's for: Owners of a stack of hopelessly dog-eared Joan Didion paperbacks. —JHM

The Myth of American Idealism by Noam Chomsky and Nathan J. Robinson [NF]

What it is: A potent critique of the ideology behind America's foreign interventions and its status as a global power, and an treatise on how the nation's hubristic pursuit of "spreading democracy" threatens not only the delicate balance of global peace, but the already-declining health of our planet.

Who it's for: Chomskyites; policy wonks and casual critics of American recklessness alike. —DF

Mysticism by Simon Critchley [NF]

What it is: A study of mysticism—defined as an experience, rather than religious practice—by the great British philosopher Critchley, who mines music, poetry, and literature along the way.

Who it's for: Readers of John Gray, Jorge Luis Borges, and Simone Weil. —SMS

Q&A by Adrian Tomine [NF]

What it is: The Japanese American creator of the Optic Nerve comic book series for D&Q, and of many a New Yorker cover, shares his personal history and his creative process in this illustrated unburdening.

Who it’s for: Readers of Tomine’s melancholic, sometimes cringey, and occasionally brutal collections of comics short stories including Summer Blonde, Shortcomings, and Killing and Dying. —NodB

Sonny Boy by Al Pacino [NF]

What it is: Al Pacino's memoir—end of description.

Who it's for: Cinephiles; anyone curious how he's gonna spin fumbling Diane Keaton. —SMS

Seeing Baya by Alice Kaplan [NF]

What it is: The first biography of the enigmatic and largely-forgotten Algerian artist Baya Mahieddine, who first enchanted midcentury Paris as a teenager.

Who it's for: Admirers of Leonora Carrington, Hilma af Klint, Frida Kahlo, and other belatedly-celebrated women painters. —SMS

Absolution by Jeff VanderMeer [F]

What it is: A surprise return to the Area X, the stretch of unforbidding and uncanny coastline in the hit Southern Reach trilogy.

Who it's for: Anyone who's heard this song and got the reference without Googling it. —JHM

The Four Horsemen by Nick Curtola [NF]

What it is: The much-anticipated cookbook from the team behind Brooklyn's hottest restaurant (which also happens to be co-owned by James Murphy of LCD Soundsystem).

Who it's for: Oenophiles; thirty-somethings who live in north Williamsburg (derogatory). —SMS

Seeing Further by Esther Kinsky, tr. Caroline Schmidt [F]

What it's about: An unnamed German woman embarks on the colossal task of reviving a cinema in a small Hungarian village.

Who it's for: Fans of Jenny Erpenbeck; anyone charmed by Cinema Paradiso (not derogatory!). —SMS

Ripcord by Nate Lippens [NF]

What it's about: A novel of class, sex, friendship, and queer intimacy, written in delicious prose and narrated by a gay man adrift in Milwaukee.

Who it's for: Fans of Brontez Purnell, Garth Greenwell, Alexander Chee, and Wayne Koestenbaum. —SMS

The Use of Photography by Annie Ernaux and Marc Marie, tr. Alison L. Strayer [NF]

What it's about: Ernaux's love affair with Marie, a journalist, while she was undergoing treatment for cancer, and their joint project to document their romance.

Who it's for: The Ernaux hive, obviously; readers of Sontag's On Photography and Janet Malcolm's Still Pictures. —SMS

Nora Ephron at the Movies by Ilana Kaplan [NF]

What it is: Kaplan revisits Nora Ephron's cinematic watersheds—Silkwood, Heartburn, When Harry Met Sally, You've Got Mail, and Sleepless in Seattle—in this illustrated book. Have these iconic stories, and Ephron’s humor, weathered more than 40 years?

Who it’s for: Film history buffs who don’t mind a heteronormative HEA; listeners of the Hot and Bothered podcast; your coastal grandma. —NodB

[millions_email]

The Philosophy of Translation by Damion Searls [NF]

What it is: A meditation on the act and art of translation by one of today's most acclaimed practitioners, best known for his translations of Fosse, Proust, et al.

Who it's for: Regular readers of Words Without Borders and Asymptote; professional and amateur literary translators alike. —SMS

Salvage by Dionne Brand

What it is: A penetrating reevaluation of the British literary canon and the tropes once shaped Brand's reading life and sense of self—and Brand’s first major work of nonfiction since her landmark A Map to the Door of No Return.

Who it's for: Readers of Christina Sharpe's Ordinary Notes and Elizabeth Hardwick's Seduction and Betrayal. —SMS

Masquerade by Mike Fu [F]

What it's about: Housesitting for an artist friend in present-day New York, Meadow Liu stumbles on a novel whose author shares his name—the first of many strange, haunting happenings that lead up to the mysterious disappearance of Meadow's friend.

Who it's for: fans of Ed Park and Alexander Chee. —SMS

November

The Beggar Student by Osamu Dazai, tr. Sam Bett [F]

What it is: A novella in the moody vein of Dazai’s acclaimed No Longer Human, following the 30-something “fictional” Dazai into another misadventure spawned from a hubristic spat with a high schooler.

Who it's for: Longtime readers of Dazai, or new fans who discovered the midcentury Japanese novelist via TikTok and the Bungo Stray Dogs anime. —DF

In Thrall by Jane DeLynn [F]

What it is: A landmark lesbian bildungsroman about 16-year-old Lynn's love affair with her English teacher, originally published in 1982.

Who it's for: Fans of Joanna Russ's On Strike Against God and Edmund White's A Boy's Own Story —SMS

Washita Love Child by Douglas Kent Miller [NF]

What it is: The story of Jesse Ed Davis, the Indigenous musician who became on of the most sought after guitarists of the late '60s and '70s, playing alongside B.B. King, Bob Dylan, John Lennon, and more.

Who it's for: readers of music history and/or Indigenous history; fans of Joy Harjo, who wrote the foreword. —SMS

Set My Heart on Fire by Izumi Suzuki, tr. Helen O'Horan [F]

What it is: Gritty, sexy, and wholly rock ’n’ roll, Suzuki’s first novel translated into English (following her story collection, Hit Parade of Tears) follows 20-year-old Izumi navigating life, love, and music in the underground scene in '70s Japan.

Who it's for: Fans of Meiko Kawakami, Ursula K. Le Guin, and Marlowe Granados's Happy Hour. —DF

Didion & Babitz by Lili Anolik [NF]

What it is: A dual portrait of Joan Didion and Eve Babitz, who are so often compared to—and pitted against—each other on the basis of their mutual Los Angeles milieu.

Who it's for: Fans or haters of either writer (the book is fairly pro-Babitz, often at Didion's expense); anyone who has the Lit Hub Didion tote bag. —SMS

The Endless Refrain by David Rowell [NF]

What it's about: How the rise of music streaming, demonitizing of artist revenue, and industry tendency toward nostalgia have laid waste to the musical landscape, and the future of music culture.

Who it's for: Fans of Kyle Chayka, Spence Kornhaber, and Lindsay Zoladz. —SMS

Every Arc Bends Its Radian by Sergio De La Pava [F]

What it is: A mind- and genre-bending detective story set in Cali, Colombia, that blends high-stakes suspense with rigorous philosophy.

Who it's for: Readers of Raymond Chandler, Thomas Pynchon, and Jules Verne. —SMS

Something Close to Nothing by Tom Pyun [F]

What it’s about: At the airport with his white husband Jared, awaiting a flight to Cambodia to meet the surrogate mother carrying their adoptive child-to-be, Korean American Wynn decides parenthood isn't for him, and bad behavior ensues.

Who it’s for: Pyun’s debut is calculated to cut through saccharine depictions of queer parenthood—could pair well with Torrey Peters’s Detransition, Baby. —NodB

Rosenfeld by Maya Kessler [F]

What it is: Kessler's debut—rated R for Rosenfeld—follows one Noa Simmons through the tumultuous and ultimately profound power play that is courting (and having a lot of sex with) the titular older man who soon becomes her boss.

Who it's for: Fans of Sex and the City, Raven Leilani’s Luster, and Coco Mellor’s Cleopatra and Frankenstein. —DF

Lazarus Man by Richard Price [F]

What it is: The former The Wire writer offers yet another astute chronicle of urban life, this time of an ever-changing Harlem.

Who it's for: Fans of Colson Whitehead's Crook Manifesto and Paul Murray's The Bee Sting—and, of course, The Wire. —SMS

Stranger Than Fiction by Edwin Frank [NF]

What it is: An astute curveball of a read on the development and many manifestations of the novel throughout the tumultuous 20th century.

Who it's for: Readers who look at a book's colophon before its title. —JHM

Letters to His Neighbor by Marcel Proust, tr. Lydia Davis

What it is: A collection of Proust’s tormented—and frequently hilarious—letters to his noisy neighbor which, in a diligent translation from Davis, stand the test of time.

Who it's for: Proust lovers; people who live below heavy-steppers. —DF

Context Collapse by Ryan Ruby [NF]

What it is: A self-proclaimed "poem containing a history of poetry," from ancient Greece to the Iowa Workshop, from your favorite literary critic's favorite literary critic.

Who it's for: Anyone who read and admired Ruby's titanic 2022 essay on The Waste Land; lovers of poetry looking for a challenge. —SMS

How Sondheim Can Change Your Life by Richard Schoch [NF]

What it's about: Drama professor Schoch's tribute to Stephen Sondheim and the life lessons to be gleaned from his music.

Who it's for: Sondheim heads, former theater kids, end of list. —SMS

The Serviceberry by Robin Wall Kimmerer [NF]

What it is: 2022 MacArthur fellow and botanist Kimmerer, an enrolled member of the Citizen Potawatomi Nation, (re)introduces audiences to a flowering, fruiting native plant beloved of foragers and gardeners.

Who it’s for: The restoration ecologist in your life, along with anyone who loved Braiding Sweetgrass and needs a nature-themed holiday gift. —NodB

My Heart Belongs in an Empty Big Mac Container Buried Beneath the Ocean Floor by Homeless [F]

What it is: A pseudonymous, tenderly comic novel of blue whales and Golden Arches, mental illness and recovery.

Who it's for: Anyone who finds Thomas Pynchon a bit too staid. —JHM

Yoke and Feather by Jessie van Eerden [NF]

What it's about: Van Eerden's braided essays explore the "everyday sacred" to tease out connections between ancient myth and contemporary life.

Who it's for: Readers of Courtney Zoffness's Spilt Milk and Jeanna Kadlec's Heretic. —SMS

Camp Jeff by Tova Reich [F]

What it's about: A "reeducation" center for sex pests in the Catskills, founded by one Jeffery Epstein (no, not that one), where the dual phenomena of #MeToo and therapyspeak collide.

Who it's for: Fans of Philip Roth and Nathan Englander; cancel culture skeptics. —SMS

Selected Amazon Reviews by Kevin Killian [NF]

What it is: A collection of 16 years of Killian’s funniest, wittiest, and most poetic Amazon reviews, the sheer number of which helped him earn the rarefied “Top 100” and “Hall of Fame” status on the site.

Who it's for: Fans of Wayne Koestenbaum and Dodie Bellamy, who wrote introduction and afterword, respectively; people who actually leave Amazon reviews. —DF

Cher by Cher [NF]

What it is: The first in a two-volume memoir, telling the story of Cher's early life and ascendent career as only she can tell it.

Who it's for: Anyone looking to fill the My Name Is Barbra–sized hole in their heart, or looking for something to tide them over until the Liza memoir drops. —SMS

The City and Its Uncertain Walls by Haruki Murakami, tr. Philip Gabriel [F]

What it is: Murakami’s first novel in over six years returns to the high-walled city from his 1985 story "Hard-Boiled Wonderland and the End of the World" with one man's search for his lost love—and, simultaneously, an ode to libraries and literature itself.

Who it's for: Murakami fans who have long awaited his return to fiction. —DF

American Bulk by Emily Mester [NF]

What it's about: Reflecting on what it means to "live life to the fullest," Mester explores the cultural and personal impacts of America’s culture of overconsumption, from Costco hauls to hoarding to diet culture—oh my!

Who it's for: Lovers of sustainability; haters of excess; skeptics of the title essay of Becca Rothfeld's All Things Are Too Small. —DF

The Icon and the Idealist by Stephanie Gorton [NF]

What it is: A compelling look at the rivalry between Margaret Sanger, of Planned Parenthood fame, and Mary Ware Dennett, who each held radically different visions for the future of birth control.

Who it's for: Readers of Amy Sohn's The Man Who Hated Women and Katherine Turk's The Women of NOW; anyone interested in the history of reproductive rights. —SMS

December

Rental House by Weike Wang [F]

What it's about: Married college sweethearts invite their drastically different families on a Cape Code vacation, raising questions about marriage, intimacy, and kinship.

Who it's for: Fans of Wang's trademark wit and sly humor (see: Joan Is Okay and Chemistry); anyone with an in-law problem.

Woo Woo by Ella Baxter [F]

What it's about: A neurotic conceptual artist loses her shit in the months leading up to an exhibition that she hopes will be her big breakout, poking fun at the tropes of the "art monster" and the "woman of the verge" in one fell, stylish swoop.

Who it's for: Readers of Sheena Patel's I'm a Fan and Chris Kraus's I Love Dick; any woman who is grateful to but now also sort of begrudges Jenny Offil for introducing "art monster" into the lexicon (me). —SMS

Berlin Atomized by Julia Kornberg, tr. Jack Rockwell and Julia Kornberg [F]

What it's about: Spanning 2001 to 2034, three Jewish and downwardly mobile siblings come of age in various corners of the world against the backdrop of global crisis.

Who it's for: Fans of Catherine Lacey's Biography of X and Joshua Cohen's The Netanyahus. —SMS

Sand-Catcher by Omar Khalifah, tr. Barbara Romaine [F]

What it is: A suspenseful, dark satire of memory and nation, in which four young Palestinian journalists at a Jordanian newspaper are assigned to interview an elderly witness to the Nakba, the violent 1948 expulsion of native Palestinians from Israel—but to their surprise, the survivor doesn’t want to rehash his trauma for the media.

Who it’s for: Anyone looking insight—tinged with grim humor—into the years leading up to the present political crisis in the Middle East and the decades-long goal of Palestinian autonomy. —NodB

The Shutouts by Gabrielle Korn [F]

What it's about: In the dystopian future, mysteriously connected women fight to survive on the margins of society amid worsening climate collapse.

Who it's for: Fans of Korn's Yours for the Taking, which takes place in the same universe; readers of Becky Chambers and queer-inflected sci-fi. —SMS

What in Me Is Dark by Orlando Reade [NF]

What it's about: The enduring, evolving influence of Milton's Paradise Lost on political history—and particularly on the work of 12 revolutionary readers, including Malcom X and Hannah Arendt.

Who it's for: English majors and fans of Ryan Ruby and Sarah Bakewell—but I repeat myself. —SMS

The Afterlife Is Letting Go by Brandon Shimoda [NF]

What it's about: Shimoda researches the mass incarceration of Japanese Americans during WWII, and speaks with descendants of those imprisoned, for this essay collection about the “afterlife” of cruelty and xenophobia in the U.S.

Who it’s for: Anyone to ever visit a monument, museum, or designated site of hallowed ground where traumatic events have taken place. —NodB

No Place to Bury the Dead by Karina Sainz Borgo, tr. Elizabeth Bryer [F]

What it's about: When Angustias Romero loses both her children while fleeing a mysterious disease in her unnamed Latin American country, she finds herself in a surreal, purgatorial borderland where she's soon caught in a power struggle.

Who it's for: Fans of Maríana Enriquez and Mohsin Hamid. —SMS

The Rest Is Silence by Augusto Monterroso, tr. Aaron Kerner [F]

What it is: The author of some of the shortest, and tightest, stories in Latin American literature goes long with a metafictional skewering of literary criticism in his only novel.

Who it's for: Anyone who prefers the term "palm-of-the-hand stories" to "flash fiction." —JHM

Tali Girls by Siamak Herawi, tr. Sara Khalili [F]

What it is: An intimate, harrowing, and vital look at the lives of girls and women in an Afghan mountain village under Taliban rule, based on true stories.

Who it's for: Readers of Nadia Hashimi, Akwaeke Emezi, and Maria Stepanova. —SMS

Sun City by Tove Jansson, tr. Thomas Teal [F]

What it's about: During her travels through the U.S. in the 1970s, Jansson became interested in the retirement home as a peculiarly American institution—here, she imagines the tightly knit community within one of them.

Who it's for: Fans of Jansson's other fiction for adults, much of which explores the lives of elderly folks; anyone who watched that documentary about The Villages in Florida. —SMS

Editor's note: We're always looking to make our seasonal book previews more useful to the readers, writers, and critics they're meant to serve. Got an idea for how we can improve our coverage? Tell me about it at sophia@themillions.com.

[millions_email]

At the Frontiers of the Unsayable: Bennett Sims’s A Questionable Shape

In Marilynne Robinson’s brilliant and engaging essay, “Imagination and Community,” she writes that we live on a small island that consists of what can be said, “which we tend to mistake for reality itself.” As she transforms the voices of her narrators into the sentences of her fictions, she tries to make “inroads on the vast terrain of what cannot be said — or said by me, at least.” The result has been three novels, all award winners, still selling well in dozens of languages. Now along comes A Questionable Shape, a wisely titled and rich first novel by Bennett Sims, who in his own way explores what Robinson calls “the frontiers of the unsayable.”

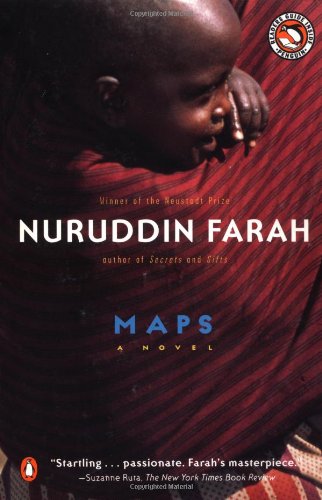

Before I go further, perhaps I should say that I am sixty-something and a picky reader, someone whose favorite novels fill a single shelf. There sit Robinson and Faulkner, Isaac Babel, Elio Vittorini, J.M. Coetzee’s Waiting for the Barbarians. Herta Müller’s Herztier, Juan Rulfo’s Pedro Páramo. Nuruddin Farah’s Maps, Javier Marías’s Your Face Tomorrow. Like Sims, I studied with Robinson. Unlike him, I have not found an easy way into the works of David Foster Wallace, with whom he also studied, and to whom he dedicates this book: “For Dave.”

On the surface, the storyline of A Questionable Shape is simple. During an epidemic of undeath that has savaged Baton Rouge and the world, a loner, plumber, and collector/hoarder has vanished and is presumed undead. His son wants to find him, even though the father he knows and loves has changed so completely that he would bite his only son and leave him incurably undead. The narrator joins the search, thereby risking being bitten, too.

“What we know about the undead so far is this: they return to the familiar,” the narrator begins. “...They will climb into their own cars and sit dumbly at the wheel, staring out the windshield into nothing. A man bitten, infected, and reanimated fifty miles from home will find his way back, staggering over diverse terrain — which, probably, he wouldn’t have recognized or been able to navigate in his mortal life — in order to stand vacantly on a familiar lawn.”

Who among us has not sat at the steering wheel of a vehicle staring into nothing, or stood vacantly on a lawn or a grassless patch of dirt staring at something no one else could see? Or, for that matter, staggered. Herein lies one strength of Sims’ novel — we are as likely at certain moments to identify with the undead as with the living: to see ourselves too easily as stunted, ravaged, hardly human.

But, dear Reader, do not be fooled. You are fully human. Also, undeath is the topic of A Questionable Shape the way Yoknapatawpha County is the topic of Faulkner, which is to say, it is merely the apparent topic, the setting, the metaphor, the externality that allows the narrator to settle in and explore the shades, shapes, and melodies of consciousness and experience. As Sims’s narrative moves forward, he uses footnotes, asides, diversions, explications, and lyrical imaginings to produce in the reader a kind of double vision of the mind, an extra set of eyes somewhere back in the head.

The two friends, both of whom are addicted to books, but in different ways, try to imagine themselves deep enough into the mind of the missing man to discover the locales he would long for in his undeath. When he was living, he lifted coffee to his lips in a certain café, browsed through the daily objects of yesteryear in a particular antiques mall, watched movies with his son in their favorite theater. But does that mean his savaged mind, reduced to its most intense nostalgias, would drag its ruined body back to any of those spots? This and other questions lead the narrator into meditations on yearning, life, death, time, memory, nostalgia, sight, insight, wisdom. On the world as it is and as it seems to be. On the perplexities of trying to know and understand the people we are closest to.

Often the narrator observes his partner closely, trying to understand her. In his recounting, these scenes become prisms of life. In one, she lies on a red blanket on the grass, intent on protecting her white sweater from grass stains, when “a rogue dead leaf” becomes enmeshed in the fine fuzz of the cashmere. “From a certain angle, this gave the brittle leaf the appearance of hovering in the air…. Beaming down at the levitating leaf, she said it looked as if it were bodysurfing on a crowd of ghosts. And by God it did: that dead leaf, brown and crispate, seemed to be borne aloft by a thousand invisible, white hands.” The allusion-loving narrator labels such moments “my private Bethlehem stars.” But Sims is fastidious in fashioning his metaphors. Readers will find meaning within meaning in those invisible white hands.

A Questionable Shape offers its readers many Bethlehem stars. For me, the first were the phrases, in an early footnote, “infected texts” and “phantom feet.” They lifted me away from the narrative and sent images flying back and forth between memory and imagination. When I returned to the page, I felt more alive, ready to move forward through the coming explorations. Reading on, I had the sense that I was tramping towards the roar of many rivers, wondering where and how they might join. Along the way, the characters and their search grew gradually more important to me, until their quest was mine, their thoughts and doubts and worries mine, their dangers mine.

Are we not every day in our own quests large and small exposed to attacks on the body, to outbreaks threatened or actual against the spirit or mind? Where I live, among the mesas and mountains of northern New Mexico, at any dawn or dusk a mountain lion could spring from behind, bite my neck and break it, giving me no chance to raise my mace and spray. I would be lucky to be merely undead. Bears here open doors, enter living rooms and kitchens, eat pies or popcorn, occasionally people. Fleas spread plague, ticks carry spotted fever. Mice with deer-like ears spray the air with Hantavirus every time they pee. A rattlesnake might sink fangs into my calf, a boulder overhead break loose and smash me, a flashflood wash me into the Río Grande. Meanwhile, chemicals leach from the earth they were carelessly buried in. I might any day tramp through an invisible, unfeelable patch of radioactivity and, with the sole of my shoe, pick up a particle containing plutonium and transport it unknowingly into the bedroom. As I set out for Santa Fe, drivers pass with bumper stickers like these: “Atomic bombs=sixty-five years of peace” and “Keep your sissy hands off my guns.”

Am I to give up the highways, the neighbors, the mesas, the state, my homeland, the planet? Am I to wear side mirrors on my glasses or devise armor, costume, incantation, poultice to keep danger away? Am I to lock myself in a room and fall undead, forfeiting beauty, mystery, pleasure, wisdom, as termites chew the roof and walls away?

A Questionable Shape is a novel for those who read in order to wake up to life, not escape it, for those who themselves like to explore the frontiers of the unsayable. I envision the core readership as brilliant and slightly disaffected men and women. In the larger circle will be fans of Anne Carson, Nicholson Baker, Rivka Galchen, Juan Rulfo, W.G. Sebald, Henry and William James, and gaggles of Russian and German writers. Also, I suspect, fans of David Foster Wallace.

There may be readers who will — on discovering that A Questionable Shape combines a quest, a romance, humor, and an epidemic of zombies, with philosophy, footnotes, history, science, the arts, half of Daniel Webster, cascades of lyricism and truckloads of realism — refuse to so much as open the back cover and peer at the author’s eyebrows. The same may be true of those who expect a novel to contain certain elements and behave in certain ways.

I wish them peace. I wish them well. I wish they would do what I so often do not, and rethink their decision.

To the rest of you I say, Climb a tree and take this book into the leaves and branches with you. Stuff it in your backpack and read it in a meadow. Take it to Dallas. Take it to New Zealand. It is more than just a novel. It is literature. It is life. It is going on my shelf between Your Face Tomorrow and Pedro Páramo.

If the skeleton standing on the corner tapping her watch and staring at me doesn’t drag me off first, I may yet find joy in reading David Foster Wallace.

My Aversion

1.

It was the fall of 2000, and I had just read David Foster Wallace’s article in Rolling Stone about his experiences hanging out with John McCain aboard the Straight Talk Express, McCain’s cannily christened campaign bus. At the time, McCain was running a spirited, if underdog, race against George W. Bush for the Republican party nomination. McCain had positioned himself as the anti-politician politician, the truth-telling everyman — an image he would reinvent as the “maverick” eight years later, only to be out-mavericked by his own running mate.

Why this strange marriage between a youth-oriented music magazine, a pop-culture savvy young writer, and a sixty-three-year-old-war-hero-turned-politician? It came about because commentators had observed that McCain’s studied lack of politicking seemed to be lifting the stupor of the country’s most politically apathetic — and thus most cherished — demographic. McCain was threatening to awaken the eighteen-to-thirty-five-year-olds who otherwise fell into a deep slumber every fourth November. “No generation of Young Voters,” Wallace announced in only the second sentence of the article, “has ever cared less about politics and politicians than yours.”

Apathy was a common trope, then as now. And although I had no statistics to disprove Wallace’s pronouncement, less than one year earlier, in late November 1999, I had watched in awe as tens of thousands of demonstrators, most of them in that eighteen to thirty-five demographic (as I was myself), descended upon the city of Seattle to protest a meeting of the World Trade Organization. United against the WTO’s policies toward labor, the environment, and economic development, the protestors effectively shut down the meeting, and the city with it — much as the Occupy Wall Street protestors are struggling to do now. The event was exactly the sort of thing we’d long been told could no longer happen — something that existed only in the dewy memories of ’60s nostalgists. My generation was said to be too cynical and self-absorbed to bother with causes. We’d given up on trying to change the world. For David Foster Wallace, our apathy was a form of sales resistance. We’d been marketed to our entire lives. Civic duty had come to seem like just another product.

But I, for one, was feeling optimistic. Maybe what had happened in Seattle was a sign that things were starting to change. Maybe apathy was giving way to engagement. That fall I was teaching composition to college freshmen. I had a classroom full of enthusiastic young students who for the first time in their lives would be old enough to vote. And I had the idea that it would be exciting to spend the semester reading essays like David Foster Wallace’s and writing about what it meant to be young, to have ideals, to live in a democracy, and to have a political voice. As I handed out the syllabus on the first day of class, gazing out upon their fresh, eager faces, I thought how satisfying it would be to prove those naysayers wrong.

The students saw the reading list. The collective groan was audible.

As it turned out, the naysayers were right.

2.

That Americans hate politics is something everyone seems to agree on, even if no one knows exactly why. Washington Post columnist E. J. Dionne has written that American hatred of politics derives from the “false polarization” created by liberalism and conservatism, a consequence of the cultural divisions that arose in the 1960s. For David Foster Wallace the culprit is the numbness of living in a consumer society. But both arguments suppose that, in the eras before Madison Avenue and Haight-Ashbury, Americans were thronging to rallies to shake hands with our beloved public servants. It may be true that we did so in larger numbers then than we do now, but there’s nevertheless a general sense that right from the start we’ve been a nation of individuals who have regarded politics with suspicion.

3.

I grew up in the suburbs of Central New York in a middle-class family with college-educated parents whose political ideologies were a complete mystery to me. To say “mystery,” though, suggests I spent any time actually wondering what their ideologies were. I didn’t. I had no idea whom they voted for, and I seldom had any idea who was even running. My after-school activities were sports, not debate club. If I looked at the newspaper, it was to study box scores. In this I was no different from any of the rest of my friends.

Like a lot of kids in my position, my own political awakening, such as it was, occurred in college, but probably not in the way it was supposed to. It was the mid-’90s, and I remember one of my first college girlfriends — a feminist when it was still fashionable to confess to being such a thing — badgering me into taking a position on abortion. “I don’t know,” I finally admitted. “I don’t know if it’s right or wrong.”

“If you don’t know,” she said, not bothering to conceal her exasperation, “that means you’re pro-choice.”

I decided to take her word for it.

The main reason I’d chosen this college — one of the lowest tier in the New York state system — was its proximity to mountains. Some people went to college to learn and to expand their horizons. I wanted to go backpacking. Also, it was one of the few colleges that would have me. My apathy for politics was exceeded only by my indifference toward school work.

But once at college, my attitude gradually began to change. My crash course in women’s rights — compliments of my girlfriend — was an important first step. I began to wonder what else I was supposed to know.

My roommate and I had no TV. The internet wasn’t yet widespread. Aside from my girlfriend, the campus had virtually no detectable political pulse. But this small mountain town, which lacked virtually everything else, at least had a public radio station. The hour in the afternoon when they broke with pallid classical music to broadcast an international news program became a fixture of my college curriculum. It was both daunting and exhilarating to discover how big the world actually was, and how little of it I understood.

By my sophomore year, backpacking was no longer enough. I’d decided I was ready for something more. So I set my mind on a plan to escape, and suddenly I found myself willing to do even the unthinkable: study. I buried myself in books, pushed myself to write, and managed to make the dean’s list. And then, before the start of my junior year, I transferred from the mountains of New York to the plains of Ohio, to a school at the opposite end of every measurable spectrum: Antioch College, a place so infamous for countercultural rabble-rousing that its bookstore sold T-shirts touting the college’s unofficial slogan, “Boot Camp for the Revolution.” Overblown rhetoric or not, the campus certainly looked like a boot camp, with barrack-like dormitories and grassless, muddy footpaths. I was both awestruck and dazed. Even though it was 1996, not 1966, at Antioch the revolution was still very much alive. The school’s official slogan, borrowed from Horace Mann, the school’s founder, was “Be ashamed to die until you have won some small victory for humanity.” Even if I wasn’t quite ready to be worrying about how my tombstone might read, I liked the idea of being surrounded by people who were. What better way to make up for all those years of indifference than full immersion at the epicenter of activism?

But in all the excitement of starting over, I forgot to ask myself one important question: where in this atmosphere did someone like me belong? Although I had managed to shake off my apathy, I had no real intention of replacing it with fervor. I was introverted and increasingly bookish. I had no ideology. I was merely curious. My Antioch classmates wanted to change the world; I mostly just wanted to write short stories.

Instead of plotting victories for humanity, I spent my college years cloistered in the tiny office of the Antioch Review, logging fiction and poetry submissions on index cards. The Antioch Review is one of the longest-running literary journals in the country. I was one of the only students at the college who knew it even existed.

The other thing Antioch is known for, besides its activist student body, is being the butt of jokes. In the early 1990s, at the height of the culture wars, the school was a cautionary tale about the perils of political correctness, culminating in a Saturday Night Live skit lampooning the school’s Sexual Offense Prevention Policy. The SOPP was a document that required verbal permission before any sort of sexual contact could be initiated.

If you missed the skit, just close your eyes and picture a trembling Chris Farley (playing a “nose tackle and a Sigma Alpha Epsilon brother”) asking a scowling Shannen Doherty, “Can I put my hands on your buttocks?”

Needless to say, Antioch has neither a football team nor fraternities. And of course, Shannen Doherty said no. Within this triangulation you find the familiar caricature of progressive politics: that it’s the exclusive domain of the humorless and dull. Antioch, though, was anything but dull. Given the proliferation of unicycles and art cars and tattoos, the place often felt more like a circus than a campus. What the SNL skit overlooked was the important fact that the SOPP had been written and introduced entirely by the students themselves. Sexual harassment on college campuses was a problem; Antioch students had decided to come up with a solution. I appreciated the bullshit-free way in which my peers had set out to fix something that they believed was broken. If I’d been asked to take part, though, I have no doubt I’d have said no.

4.

David Foster Wallace was probably right that no generation has cared less about politics than Generation Y. Then again, whoever said the same thing about my Generation X would have been right, too, as would whoever said it about the generation before that. The idea that Americans are selfish and individualistic isn’t new. There’s even a school of thought that suggests the idea is virtually as old as the nation itself, that these tendencies might be, paradoxically, an inheritance of the Puritans themselves. The Puritans’ relentless pursuit of self-denial, the argument goes, wound up turning the corner into self-indulgence. So closely did they identify themselves with the divine America that they came to feel they actually personified it. Which led, in a roundabout way, to that great American mystic, Ralph Waldo Emerson, whose preachings about self-reliance and transcendentalism begot Walt Whitman’s songs of himself; they became something of a national anthem. Ever since then, it seems, the majority of us have beat a hasty retreat from public life.

There are numerous variations on this idea, with different starting points and interpretations. Literary scholar R. W. B. Lewis calls his version of this mythic, individualist national identity “the American Adam.” He traces its evolution from Emerson to Thoreau to Whitman, and on to the early American novelists James Fenimore Cooper, Herman Melville, Nathaniel Hawthorne, and Henry James. Lewis describes the American Adam, celebrated in this literary lineage, as “an individual emancipated from history, happily bereft of ancestry, untouched and undefiled by the usual inheritances of family and race; an individual standing alone, self-reliant and self-propelling, ready to confront whatever awaited him with the aid of his own unique and inherent resources.” The American Adam is a figure of pure innocence, focused inward, detached from the larger concerns of the world. He is Adam before the Fall.

5.

If I was failing to become everything Horace Mann might have wanted me to be, I at least got out of my time at Antioch an awareness of the complicated matrix of political issues surrounding everything we do, including the telling of stories. I learned that even great works of literature were products of social values and ideas, too many of which often went unexamined. I came to understand instinctively what George Orwell meant when he wrote, three decades before Fredric Jameson, that “no book is genuinely free from political bias. The opinion that art should have nothing to do with politics is itself a political attitude.”

While at Antioch, my tolerance toward the compatibility of literature and politics gradually grew. I developed an interest — sacrilegious for a budding writer — in critical theory: Marxists and postcolonialists and postmodernists. The whole solemn crowd. I spent a seminar on Toni Morrison deconstructing the ways in which Beloved, Song of Solomon, Sula, and her other novels blended controversial social issues such as slavery and race with high art.

During the two years I spent at Antioch, my opinions did eventually grow stronger, my convictions more firm. My admiration grew as well for my classmates — for their passion and determination. They were as far from the American Adam as one could get. And yet, I didn’t try to emulate them. Or even to join them. I remained probably the only student at Antioch who took no part in demonstrations. Whenever my classmates were organizing and meeting and debating, I was somewhere else.

As was my tendency with most things, I fed my fascination with political activism by reading. I read everything I could find: Raoul Vaneigem’s The Revolution of Everyday Life, histories of the Situationists, the SDS, the Weather Underground, the Red Army Faction, the Angry Brigade. I read Hakim Bey and borrowed whatever dog-eared tracts my friends had lying around. I was like an anthropologist trying to decipher some exotic alien society. I wanted to understand their culture, their myths and religion. I wanted to know what propelled them. I wanted to know, in short, what made them so different from me.

In time I learned that there were things I lacked that true activists, like my classmates, had in abundance. Above all else, a tolerance for confrontation and a productive ability to channel anger. My instincts were hopelessly reversed. When it came to the issues I cared about most, what got triggered within me was more often flight than fight. The injustices of the world made me indignant, but more than that, they made me depressed. And the only way to escape the depression was to detach. This has remained true even as I’ve gotten older. My attraction for politics is still, more often than not, outweighed by my aversion.

In 2000, when George W. Bush was handed the presidency through a Supreme Court decision, it was the process that I wanted my students to be interested in. What mattered was taking part and caring, not about the outcome, but about why a thing like democracy was important.

In 2004, when Bush was reelected, I turned my radio off, and I’m not exaggerating when I say a year passed before I was able to turn it back on.

6.

My attempt to interest that class of freshmen in writing about what it meant to be political was far from a success. The fault for its failure was undoubtedly mine. After all, how could I expect them to unravel their complicated feelings about democracy and political identity when I was still struggling to do so myself?

But even after the class was over and I packed my syllabus permanently away, these questions about my political self continued to nag at me. Then, in 2002, I happened to read an article in the New York Times about the difficult political situation in Haiti. The focus of the article was an enormous estate on that tumultuous island that had become occupied by armed gangs. In addition to being the site of a once-lavish hotel, the estate was also said to contain the last scrap of the island’s ravaged tropical rainforest. Against the armed intruders the article pitted the estate’s caretaker, a white Canadian whose mission was to try to save the estate, particularly the forest, from oblivion. (This was almost eight years before the devastating earthquake and cholera epidemic.) At the time, my knowledge of Haiti was sketchy, but I knew it was a place embroiled in unrest. I couldn’t help wondering what it meant that this Edenic estate had ever existed here, and what it meant for someone to be trying to preserve it amid widespread environmental destruction and political upheaval.

My desire to understand the complex situation there led me to a related article from twenty-seven years earlier. “A New Retreat for the Rich — Surrounded by Tumbledown Shacks” documented a party held to celebrate the opening of the hotel on that very estate in January 1974 (a year and a half before I was born). With a mixture of bewilderment and contempt, its author described the jet-setters and society figures gathered poolside in tuxedos and diamonds, utterly oblivious of the dire poverty and political instability surrounding them even then. The hotel had been built atop a powder keg. In fact, the earlier article could in retrospect be said to predict the one that would first catch my eye more than a quarter century later.

There was also a seemingly minor detail that both articles mentioned in passing. But this detail captured my imagination almost as much as the rest: at the turn of the nineteenth century the estate had been the home of Charles Leclerc, a French general who in 1801 had been sent by his brother-in-law, Napoleon Bonaparte, to restore slavery on the French colony. Since 1791, the slaves, led in part by Toussaint L’Ouverture, had been fighting to win their independence. Not long after they succeeded, Napoleon dispatched Leclerc to take it back.

But despite his warships and his forty thousand troops, Leclerc’s army was decimated. The general himself succumbed to yellow fever. His successor, Rochambeau, fared no better. Although L’Ouverture would not live to see it, the war he had helped to wage became the first successful slave rebellion in history. In 1804, Haiti became the world’s first independent black republic.

This bloody episode was not, however, the end of Haiti’s troubles. It was instead the beginning of a different struggle. The following two hundred years have been characterized by nearly perpetual autocratic rule and fairly regular American meddling. At the time of my initial research, Haiti was in the midst of a difficult transition to democracy. The country’s first popularly elected president, Jean-Bertrand Aristide, brought to power in 1990, had already been overthrown once by a military coup. He’d been reelected in 2000 for a second term, but alleged irregularities and deep divisions among the electorate had created a tense, often violent atmosphere.

Amy Wilentz’s Rainy Season chronicles the plight of Haiti’s poor and the rise of Aristide, their champion, from firebrand priest to politician. The book is the story of a nation that for generations has suffered oppression most Americans can barely fathom. But the book also makes clear that this is not a nation of passive victims. In Haiti, brutality has always met resistance. The struggles of individuals, communities, and the populace as a whole reveal a relentless determination to see justice done — a determination still plainly visible in the midst of post-earthquake reconstruction and a new round of democratic elections.

For many Americans, politics is an abstraction, something that happens somewhere else, overseen by people we pay to handle things so we don’t have to think about them. In a place like Haiti, I came to see, politics is virtually inescapable. In 1964, while in exile during the reign of dictator Françoise Duvalier, Haitian scholar (and future president) Leslie Manigat wrote of the situation back home, “Everything is political... The reputation earned by an engineer in his special field is regarded as a political trump. The prestige that a professor gains among his students may represent a political threat to the government... Such is the encroachment of politics on all aspects of life that if a man does not go into politics, politics itself comes to him.”

Poring over newspaper articles from the country’s recent past, I found one from 1987, not long after the thirty-year father-and-son Duvalier dictatorship finally came to an end. The constitutionally required “free and fair” elections scheduled for that year — the nation’s first — pitted candidates from numerous camps against one another. And as the ruling military junta began to realize that it stood no chance of retaining power, they concluded that their only recourse was to stop the election from taking place. This they accomplished by orchestrating a campaign of violence culminating in a daylight attack on a school where at least two dozen men, women, and children were slaughtered while waiting to vote.

Could there be any more stark a contrast than between David Foster Wallace’s bemoaning of voter apathy in the U.S. and the situation in Haiti, where in 1987, daring to vote could get a person killed, and where people persisted in doing it anyway? For most of us, the impossibility of something like this happening in our own lives, in our own country, makes the horror feel pretty abstract, too. We can’t conceive of such a world, even though it’s less than a two-hour flight from Miami.

The more I read about Haiti, the more I came to believe that conceiving of such a world is one of the most important things literature can do. And I realized that some of my favorite novels, the ones to which I felt the greatest affinity, were concerned with politically averse individuals caught in the middle of similarly fraught political situations. I’m thinking, for instance, of Roberto Bolaño’s By Night in Chile, which depicts the complicity in dictatorial brutality of a priest who wants nothing more than to be a poet. The Beautyful Ones Are Not Yet Born, by Ayi Kwei Armah, places a government clerk stricken with malaise in the center of Ghanaian political and social turmoil. And many of J. M. Coetzee’s novels explore this terrain, too, including Waiting for the Barbarians, in which an unnamed magistrate wishes to disassociate himself from the evils of the empire he serves. It’s worth noting that none of these are American novels. Which suggests that maybe political aversion isn’t limited to our shores after all.

It probably shouldn’t be surprising then that the book I came to write, based in part on the events I’d been reading about in Haiti, also placed political aversion at its core. I don’t think it was a conscious decision, but it was clearly a symptom of what my mind was working through. I couldn’t help asking, as I looked back on my own complicated relationship with politics: if I had been born in such a place, how might I have been different? Might I have been stronger, someone with the courage to take a stand? Or might I have found a way to be the same detached observer that I am? Or something even more extreme: a true American Adam, determined to remain innocent in a place where such a luxury seemed inconceivable, where attempts to secure it were doomed to fail? These questions felt important to me.

But the questions also felt personal. It soon became clear that despite writing about someone whose circumstances and skin color and place of birth could hardly have been more different from my own, I was writing in large part about myself. In fact, I was writing, albeit in a much different form, the sort of thing I had asked my students to write back in 2000 — about what it meant to have ideals and a political voice, and about the strength it sometimes took to express them, especially when it was so much easier not to. It’s taken me more than ten years to do what I hoped they could accomplish in a semester. Little did I know how difficult an assignment it would turn out to be.

Image: 2006 election in Haiti via Wikimedia

A Year in Reading: Sigrid Nunez

I began 2010 in Provincetown reading J. M. Coetzee’s latest book, Summertime. Though published as a novel, Summertime can be read as a sequel to Coetzee’s two volumes of memoir, Boyhood: Scenes from Provincial Life and Youth: Scenes from Provincial Life II, both of which Coetzee wrote in the third person. In Summertime, a famous writer named John Coetzee has died. The book is made up largely of a young biographer’s interviews with various people (all but one female) who once knew the writer. Much of what these people have to say is unflattering, at times contemptuous and even cruel. When their words are put together with excerpts from the writer’s journals, a fascinating—if less than lovable—portrait of “Coetzee” emerges. This is a strange, poignant, and often very funny hybrid of a book, though, for me, not quite as haunting as the earlier autobiographical works, particularly Boyhood.

The end of 2010 finds me in Marfa, Texas, reading Coetzee again. Coetzee has long been a favorite writer of mine, the restraint and asceticism of his short books making so much other literary writing seem undisciplined and turgid by comparison. I had read almost all his work, but in the house where I’m staying I found two novels I hadn’t gotten around to yet: The Age of Iron and Life and Times of Michael K. The bleakness of the characters’ lives (hopelessly sick, poor, friendless souls crushed by South African society’s brutal systems) makes for almost unbearable reading. Yet Coetzee seems to me one of the few contemporary writers whose work can be called "necessary" without fear of overstatement. And who else could have written Waiting for the Barbarians and Disgrace?

For years people have been urging me to read James Galvin’s The Meadow, and this year I finally did. The Meadow is the story of a particular piece of land in a mountainous region on the border of Colorado and Wyoming over a period of a century. It is both a natural history of the place and a portrait of the various people—ordinary in some ways, utterly extraordinary in others—who have struggled to make their lives there. As the meadow lies on the border of two states, so The Meadow lies between fiction and nonfiction. Not like any other book I’ve ever read, almost a new genre, it contains passages as beautifully written as anything in American literature. When I read work as fine as that of either of these two wonderful writers I think: I’ll write like that in heaven.

More from a Year in Reading 2010

Don't miss: A Year in Reading 2009, 2008, 2007, 2006, 2005

The good stuff: The Millions' Notable articles

The motherlode: The Millions' Books and Reviews

Like what you see? Learn about 5 insanely easy ways to Support The Millions

Known Answers and Unknown Questions: J.M. Coetzee’s The Master of Petersburg

Why did J.M. Coetzee write The Master of Petersburg?

I mean this as an existential question; the purpose of the novel itself is unusually explicit: not content to be merely “Dostoevskian” in tone, Coetzee’s protagonist actually is Fyodor Dostoevsky, and the story is a fictional account of events in Dostoevsky’s life prior to, and leading to, his writing of the novel Demons. In that way, Master of Petersburg is a sort of reverse mathematical problem. Given a set of factors, it is a matter of simple calculation to derive their product. But what if you start with the product - can you work backwards to discover the original sum from which that product was derived? The possibilities, particular with a large, complex figure, would be infinite. Here, the novel Demons is the product, the effect, the outcome. And from the known answer, Coetzee imagines the unknown questions.

Set in Russia in 1869, Master of Petersburg follows “Dostoevsky’s” grief-stricken return to St. Petersburg after news of the death of his stepson, Pavel, for whom he felt a profound though inscrutable love. While living in Pavel’s old room, he develops a sexual relationship with Pavel’s old landlady, the widow Anna Sergeyevna, along with a fascination with her adolescent daughter, Matryosha. As he becomes increasingly enmeshed in the enigma of his stepson’s death, he discovers Pavel was a member of the nihilist Sergei Nechayev’s revolutionary gang. Nechayev, who is living in hiding, has all the while been scheming to trap Dostoyevsky so to exploit his fame as an author by forcing him to write a pamphlet endorsing the Nechayevite philosophy. Out of these ultimately ambiguous social and political interactions, Dostoevsky begins writing a new novel, ostensibly Demons, in the last chapter of the book.

This plot lies at the murky intersection between fact and two fictions, Coetzeean fiction and Dostoevskian fiction (i.e., Demons). Several elements are based in fact: Dostoevsky did have a stepson named Pavel, who was likewise something of an enigma, although he survived his stepfather. Sergei Nechayev was a real Russian nihilist and revolutionary, and his association with the 1869 murder of a fellow student, Ivanov, partly inspired Dostoevsky to write Demons, where he portrays such idealists of his time as demonic. But the story also draws from the plot of Demons itself, most heavily from "At Tikhon's," a chapter originally suppressed by Dostoevsky’s editors, in which the character Stavrogin confesses to having once seduced his landlord's 12-year old daughter, Matryosha, and driven her to suicide. And finally, to this heady mix Coetzee adds some fiction of his own.

You have to give Coetzee credit for this undertaking, this deconstruction of both the power and process of writing. As a prominent South African writer, no doubt Coetzee was keen to examine the political power of the authorial voice, through Nechayev’s belief in the import of having a famous writer pen the words of a revolutionary pamphlet - and the extreme measures he would take to bring about such a coup. Equally contemplated is the personal power of writing, as it is a means for "Dostoevsky" to access his son, to “give up his soul” so as to “meet him in death.”

But when it comes to the process of writing, you can’t escape the fact that this is not Dostoevsky writing about Dostoevsky writing. It is Coetzee writing about “Dostoevsky” writing. Given this structure, it’s Coetzee’s own role in solving the reverse mathematical problem that compels above all. Why did he choose what he did, from fact, from Dostoevskian fiction, and from Coetzeean fiction? Moreover, Demons is not a novel in a vacuum: many of Dostoevsky’s real-life inspirations are documented, yet Coetzee replaces several of these with fictional inspirations of his own design. Is Master of Petersburg then an account of a fictional writing process? Or is Coetzee laying his own writing process bare?

It’s nearly impossible not to be sidetracked by these thought experiments while reading Master of Petersburg. The fact that much of the (Dostoevskian) fictional parts of the plot are dedicated to Demon’s excised chapter involving the young girl’s molestation is particularly distracting. Coetzee is not alone in holding Stavrogin’s confession as integral to Demons: while some think that Dostoevsky himself was dissatisfied with the confession, others view the forced excision of what was an indispensable chapter as rendering the novel morally asymmetrical. But the extent to which “At Tikhon’s” aligns Demons is not my issue; rather, it is “Dostoevsky’s” largely unexplained tendency to continually attach a sexual subtext to the young girl Matryosha’s interactions, whether with Nechayev, with a sort of version of Pavel that he imagines in the future, or even with himself.

[Dostoyevsky] has no difficulty in imagining this child in her ecstasy... This is as far as the violation goes: the girl in the crook of his arm, the five fingers of his hand, white and dumb, gripping her shoulder. But she might as well be sprawled out naked...

It's eventually jarring how Coetzee deliberately (and repeatedly) advocates that “Dostoevsky” would be prompted by his own perception of a young girl as above all a sexual object to conceive of the particular molestation scene described in Stavrogin’s confession. I’m not implying this rings false (though it's somewhat overdone), just that it highlights the major weakness of Coetzee’s particular form of the reverse math problem as fiction: the reader is often far more preoccupied with why Coetzee made his choices than with the choices themselves.

This brings me back to my original, existential question: why did Coetzee write Master of Petersburg? It’s an inspired project, but by its own premise it is merely an experiment, a study, rather than a novel. Coetzee has been criticized for his metafiction before: his 1986 novel Foe, which weaves its plot around Robinson Crusoe, drew him criticism for being a disappointingly politically irrelevant work coming from one of South Africa’s most lauded writers. The New York Times concluded that “the novel - which remains somewhat solipsistically concerned with literature and its consequences - lacks the fierceness and moral resonance of [Waiting for the Barbarians] and [Life and Times of Michael K]...”

However, my criticism of Master of Petersburg is of the literary, not political, variety. Countless excellent novels have been inspired by existing works, but though Coetzee’s writing is stunning, the story, composed of curious but ultimately inconclusive events, never takes hold. It offers much by way of intellectual exercise, but on its own fails to satisfy. More autonomous novels similarly fashioned out of vague questions and ideas contain a central truth or truths that are not merely valuable, but in a sense new, and that have thus driven the author to sit down to write. Here, the underlying purpose, the answer, exists in another novel altogether. And as it turns out, Dostoevsky's answer is more interesting than Coetzee's questions.

My Favorites’ Favorites

1.

Many of my favorite books – Dracula, The Rings of Saturn, A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man – came to me as assigned reading. Even more than specific titles, I inherited my favorite authors from professors: Nicholson Baker, Harryette Mullen, Turgenev, George Saunders.

This literary bestowal carries on into adulthood as I seek my favorite authors’ favorite authors. At HTMLGIANT, Blake Butler started a broad compendium of David Foster Wallace’s favorite works, encompassing books he blurbed, books assigned on his syllabus, books mentioned in interviews and in passing. It is a nourishing list, a place to turn when I think about what I should read next.

But my road with the recommendations of my favorite authors has been unpaved and rocky.

I devoured U and I, Nicholson Baker’s endearing, humorous volume on John Updike. I loved that he read the copyright page of each Updike book, tracing where essays or excerpts had been previously published. U and I is about Updike, yes, but it is more about Baker wrestling with Updike’s impact on a personal level. Early in the book he lays it out: “I was not writing an obituary or a traditional critical study, I was trying to record how one increasingly famous writer and his books, read and unread, really functioned in the fifteen or so years of my life since I had first become aware of his existence…”

Because the book is about Baker not about Updike, I found it easy to like. Baker recounts the 125th anniversary party for The Atlantic where Tim O’Brien tells him that he and Updike golf together: “I was of course very hurt that out of all the youngish writers in the Boston area, Updike had chosen Tim O’Brien and not me as his golfing partner. It didn’t matter that I hadn’t written a book that had won a National Book Award, hadn’t written a book of any kind, and didn’t know how to golf.”

And so, under Baker’s tutelage, I read John Updike. More accurately, I tried to read Updike, tried and tried. Rabbit, Run. Pigeon Feathers. The Poorhouse Fair. I didn’t finish any of them, I barely started them. I would have scoured Couples for the passage where Updike compares a vagina to a ballet slipper – which Baker mentions – if I could have gotten through the second chapter.

After quoting his own mother and Nabokov, Baker tells me, “There is no aphoristic consensus to deflect and distort the trembly idiosyncratic paths each of us may trace in the wake of the route that the idea of Updike takes through our consciousness.” Updike is not an idea that is tracing its way – neither trembling nor idiosyncratic – through my consciousness. There is no Updike boat leaving a wake in the waves of my mind like a yacht leaving Cape Cod for the Vineyard.

Rather than accept that Baker and I – being of different eras and different genders – have different taste, I concluded that I must be intellectually and creatively deficient; I am a bad reader. I was disappointed in myself for disappointing the Nicholson Baker in my mind, shaking his bearded head, tut-tutting at me: Poor girl, she’ll never understand.

A few months ago I picked up The Anthologist and started it, in the midst of other selections. (When the book came out last September, I actually drove twenty miles to Marin to see Baker read. I was the youngest member of the audience by thirty years. But I am afraid to buy a book at a reading, and petrified of the prospect of having an author sign the book. I could make a fool of myself as Baker did when asking Updike to sign a book in the early 80s.)

Then a couple weeks ago I received a mass email from a writer I know about how he was reading The Anthologist, and I felt the urge to pick it up again. He even said, “I’m really loving The Anthologist.”

I haven’t read everything by Baker, but I’ve read a bunch and enjoyed it on my own; yet, his authoritative praise weighs more than my own evaluation.

2.

Recently in Maine in a used bookstore (that was also the bookseller’s refurbished garage), I stumbled on three of Carson McCullers’ books for $1 each. (In case you are wondering, and you should be wondering, I was not close to Nicholson Baker’s home in Maine, but further up the coast near E.B. White’s former home, near the county fair where Fern bought Wilbur.) The cover of the tattered McCullers paperback proclaimed “One of the finest writers of our time” from The New York Times. I couldn’t recall exactly where I’d heard her name, but it was vaguely familiar. I bought all three.

I started The Ballad of the Sad Café and she drew me into her vivid, textured Southern world. Her descriptions are precise ideas: “The hearts of small children are delicate organs. A cruel beginning in this world can twist them into curious shapes.”

She commands the reader and directs me what to do: “See the hunchback marching in Miss Amelia’s footsteps when on a red winter morning they set out for the pinewoods to hunt… See them working on her properties… So compose from such flashes an image of these years as a whole. And for a moment let it rest.” This second-person imperative jumped out of the smooth, poetic narrative, but it fit like a nest on a tree. McCullers is unafraid to acknowledge you and make you do what she thinks you should. Yet she maintains authorial distance and control by refraining from the first person while directing your attention like a gentle guide: “Now some explanation is due for all this behavior,” she opens an aside on the nature of love. She then elides authority by saying, “It has been mentioned before that Miss Amelia was once married.”