Mentioned in:

A Year in Reading: 2024

Welcome to the 20th (!) installment of The Millions' annual Year in Reading series, which gathers together some of today's most exciting writers and thinkers to share the books that shaped their year. YIR is not a collection of yearend best-of lists; think of it, perhaps, as an assemblage of annotated bibliographies. We've invited contributors to reflect on the books they read this year—an intentionally vague prompt—and encouraged them to approach the assignment however they choose.

In writing about our reading lives, as YIR contributors are asked to do, we inevitably write about our personal lives, our inner lives. This year, a number of contributors read their way through profound grief and serious illness, through new parenthood and cross-country moves. Some found escape in frothy romances, mooring in works of theology, comfort in ancient epic poetry. More than one turned to the wisdom of Ursula K. Le Guin. Many describe a book finding them just when they needed it.

Interpretations of the assignment were wonderfully varied. One contributor, a music critic, considered the musical analogs to the books she read, while another mapped her reads from this year onto constellations. Most people's reading was guided purely by pleasure, or else a desire to better understand events unfolding in their lives or larger the world. Yet others centered their reading around a certain sense of duty: this year one contributor committed to finishing the six Philip Roth novels he had yet to read, an undertaking that he likens to “eating a six-pack of paper towels.” (Lucky for us, he included in his essay his final ranking of Roth's oeuvre.)

The books that populate these essays range widely, though the most commonly noted title this year was Tony Tulathimutte’s story collection Rejection. The work of newly minted National Book Award winner Percival Everett, particularly his acclaimed novel James, was also widely read and written about. And as the genocide of Palestinians in Gaza enters its second year, many contributors sought out Isabella Hammad’s searing, clear-eyed essay Recognizing the Stranger.

Like so many endeavors in our chronically under-resourced literary community, Year in Reading is a labor of love. The Millions is a one-person editorial operation (with an invaluable assist from SEO maven Dani Fishman), and producing YIR—and witnessing the joy it brings contributors and readers alike—has been the highlight of my tenure as editor. I’m profoundly grateful for the generosity of this year’s contributors, whose names and entries will be revealed below over the next three weeks, concluding on Wednesday, December 18. Be sure to subscribe to The Millions’ free newsletter to get the week’s entries sent straight to your inbox each Friday.

—Sophia Stewart, editor

Becca Rothfeld, author of All Things Are Too Small

Carvell Wallace, author of Another Word for Love

Charlotte Shane, author of An Honest Woman

Brianna Di Monda, writer and editor

Nell Irvin Painter, author of I Just Keep Talking

Carrie Courogen, author of Miss May Does Not Exist

Ayşegül Savaş, author of The Anthropologists

Zachary Issenberg, writer

Tony Tulathimutte, author of Rejection

Ann Powers, author of Traveling: On the Path of Joni Mitchell

Lidia Yuknavitch, author of Reading the Waves

Nicholas Russell, writer and critic

Daniel Saldaña París, author of Planes Flying Over a Monster

Lili Anolik, author of Didion and Babitz

Deborah Ghim, editor

Emily Witt, author of Health and Safety

Nathan Thrall, author of A Day in the Life of Abed Salama

Lena Moses-Schmitt, author of True Mistakes

Jeremy Gordon, author of See Friendship

John Lee Clark, author of Touch the Future

Ellen Wayland-Smith, author of The Science of Last Things

Edwin Frank, publisher and author of Stranger Than Fiction

Sophia Stewart, editor of The Millions

A Year in Reading Archives: 2023, 2022, 2021, 2020, 2019, 2018, 2017, 2016, 2015, 2014, 2013, 2011, 2010, 2009, 2008, 2007, 2006, 2005

The Great Fall 2024 Book Preview

With the arrival of autumn comes a deluge of great books. Here you'll find a sampling of new and forthcoming titles that caught our eye here at The Millions, and that we think might catch yours, too. Some we’ve already perused in galley form; others we’re eager to devour based on their authors, plots, or subject matters. We hope your next fall read is among them.

—Sophia Stewart, editor

October

Season of the Swamp by Yuri Herrera, tr. Lisa Dillman [F]

What it is: An epic, speculative account of the 18 months that Benito Juárez spent in New Orleans in 1853-54, years before he became the first and only Indigenous president of Mexico.

Who it's for: Fans of speculative history; readers who appreciate the magic that swirls around any novel set in New Orleans. —Claire Kirch

The Black Utopians by Aaron Robertson [NF]

What it is: An exploration of Black Americans' pursuit and visions of utopia—both ideological and physical—that spans the Reconstruction era to the present day and combines history, memoir, and reportage.

Who it's for: Fans of Saidiya Hartman's Wayward Lives, Beautiful Experiments and Kristen R. Ghodsee's Everyday Utopia. —Sophia M. Stewart

The Third Realm by Karl Ove Knausgaard, tr. Martin Aitken [F]

What it is: The third installment in Knausgaard's Morning Star series, centered on the appearance of a mysterious new star in the skies above Norway.

Who it's for: Real Knausgaard heads only—The Wolves of Eternity and Morning Star are required reading for this one. —SMS

Brown Women Have Everything by Sayantani Dasgupta [NF]

What it is: Essays on the contradictions and complexities of life as an Indian woman in America, probing everything from hair to family to the joys of travel.

Who it's for: Readers of Durga Chew-Bose, Erika L. Sánchez, and Tajja Isen. —SMS

The Plot Against Native America by Bill Vaughn [F]

What it is: The first narrative history of Native American boarding schools— which aimed "civilize" Indigenous children by violently severing them from their culture— and their enduring, horrifying legacy.

Who it's for: Readers of Ned Blackhawk and Kathleen DuVal. —SMS

The Mighty Red by Louise Erdrich [F]

What it is: Erdrich's latest novel set in North Dakota's Red River Valley is a tale of the intertwined lives of ordinary people striving to survive and even thrive in their rural community, despite environmental upheavals, the 2008 financial crisis, and other obstacles.

Who it's for: Readers of cli-fi; fans of Linda LeGarde Grover and William Faulkner. —CK

The Position of Spoons by Deborah Levy [NF]

What it is: The second book from Levy in as many years, diverging from a recent streak of surrealist fiction with a collection of essays marked by exceptional observance and style.

Who it's for: Close lookers and the perennially curious. —John H. Maher

The Bog Wife by Kay Chronister [F]

What it's about: The Haddesley family has lived on the same West Virginia bog for centuries, making a supernatural bargain with the land—a generational blood sacrifice—in order to do so—until an uncovered secret changes everything.

Who it's for: Readers of Karen Russell and Jeff VanderMeer; anyone who has ever used the phrase "girl moss." —SMS

The Great When by Alan Moore [F]

What it's about: When an 18-year old book reseller comes across a copy of a book that shouldn’t exist, it threatens to upend not just an already post-war-torn London, but reality as we know it.

Who it's for: Anyone looking for a Sherlock Holmes-style mystery dipped in thaumaturgical psychedelia. —Daniella Fishman

The Message by Ta-Nehisi Coates [NF]

What it's about: One of our sharpest critical thinkers on social justice returns to nonfiction, nearly a decade after Between the World and Me, visiting Dakar, to contemplate enslavement and the Middle Passage; Columbia, S.C., as a backdrop for his thoughts on Jim Crow and book bans; and the Israeli-occupied West Bank, where he sees contemporary segregation in the treatment of Palestinians.

Who it’s for: Fans of James Baldwin, George Orwell, and Angela Y. Davis; readers of Nikole Hannah-Jones’s The 1619 Project and Isabel Wilkerson’s Caste, to name just a few engagements with national and racial identity. —Nathalie op de Beeck

Abortion by Jessica Valenti [NF]

What it is: Columnist and memoirist Valenti, who tracks pro-choice advocacy and attacks on the right to choose in her Substack, channels feminist rage into a guide for freedom of choice advocacy.

Who it’s for: Readers of Robin Marty’s The New Handbook for a Post-Roe America, #ShoutYourAbortion proponents, and followers of Jennifer Baumgartner’s [I Had an Abortion] project. —NodB

Gifted by Suzuki Suzumi, tr. Allison Markin Powell [F]

What it's about: A young sex worker in Tokyo's red-light district muses on her life and recounts her abusive mother's final days, in what is Suzuki's first novel to be translated into English.

Who it's for: Readers of Susan Boyt and Mieko Kanai; fans of moody, introspective fiction; anyone with a fraught relationship to their mother. —SMS

Childish Literature by Alejandro Zambra, tr. Megan McDowell [F]

What it is: A wide-ranging collection of stories, essays, and poems that explore childhood, fatherhood, and family.

Who it's for: Fans of dad lit (see: Lucas Mann's Attachments, Keith Gessen's Raising Raffi, Karl Ove Knausgaard's seasons quartet, et al). —SMS

Books Are Made Out of Books ed. Michael Lynn Crews [NF]

What it is: A mining of the archives of the late Cormac McCarthy with a focus on the famously tight-lipped author's literary influences.

Who it's for: Anyone whose commonplace book contains the words "arquebus," "cordillera," or "vinegaroon." —JHM

Slaveroad by John Edgar Wideman [F]

What it is: A blend of memoir, fiction, and history that charts the "slaveroad" that runs through American history, spanning the Atlantic slave trade to the criminal justice system, from the celebrated author of Brothers and Keepers.

Who it's for: Fans of Clint Smith and Ta-Nehisi Coates. —SMS

Linguaphile by Julie Sedivy [NF]

What it's about: Linguist Sedivy reflects on a life spent loving language—its beauty, its mystery, and the essential role it plays in human existence.

Who it's for: Amateur (or professional) linguists; fans of the podcast A Way with Words (me). —SMS

An Image of My Name Enters America by Lucy Ives [NF]

What it is: A collection of interrelated essays that connect moments from Ives's life to larger questions of history, identity, and national fantasy,

Who it's for: Fans of Ives, one of our weirdest and most wondrous living writers—duh; anyone with a passing interest in My Little Pony, Cold War–era musicals, or The Three Body Problem, all of which are mined here for great effect. —SMS

Women's Hotel by Daniel Lavery [F]

What it is: A novel set in 1960s New York City, about the adventures of the residents of a hotel providing housing for young women that is very much evocative of the real-life legendary Barbizon Hotel.

Who it's for: Readers of Mary McCarthy's The Group and Rona Jaffe's The Best of Everything. —CK

The World in Books by Kenneth C. Davis [NF]

What it is: A guide to 52 of the most influential works of nonfiction ever published, spanning works from Plato to Ida B. Wells, bell hooks to Barbara Ehrenreich, and Sun Tzu to Joan Didion.

Who it's for: Lovers of nonfiction looking to cover their canonical bases. —SMS

Blue Light Hours by Bruna Dantas Lobato [F]

What it's about: Through the emanating blue-glow of their computer screens, a mother and daughter, four-thousand miles apart, find solace and loneliness in their nightly Skype chats in this heartstring-pulling debut.

Who it's for: Someone who needs to be reminded to CALL YOUR MOTHER! —DF

Riding Like the Wind by Iris Jamahl Dunkle [NF]

What it is: The biography of Sanora Babb, a contemporary of John Steinbeck's whose field notes and interviews with Dust Bowl migrants Steinbeck relied upon to write The Grapes of Wrath.

Who it's for: Steinbeck fans and haters alike; readers of Kristin Hannah's The Four Winds and the New York Times Overlooked column; anyone interested in learning more about the Dust Bowl migrants who fled to California hoping for a better life. —CK

Innie Shadows by Olivia M. Coetzee [F]

What it is: a work of crime fiction set on the outskirts of Cape Town, where a community marred by violence seeks justice and connection; also the first novel to be translated from Kaaps, a dialect of Afrikaans that was until recently only a spoken language.

Who it's for: fans of sprawling, socioeconomically-attuned crime dramas a la The Wire. —SMS

Dorothy Parker in Hollywood by Gail Crowther [NF]

What it is: A history of the famous wit—and famous New Yorker—in her L.A. era, post–Algonquin Round Table and mid–Red Scare.

Who it's for: Owners of a stack of hopelessly dog-eared Joan Didion paperbacks. —JHM

The Myth of American Idealism by Noam Chomsky and Nathan J. Robinson [NF]

What it is: A potent critique of the ideology behind America's foreign interventions and its status as a global power, and an treatise on how the nation's hubristic pursuit of "spreading democracy" threatens not only the delicate balance of global peace, but the already-declining health of our planet.

Who it's for: Chomskyites; policy wonks and casual critics of American recklessness alike. —DF

Mysticism by Simon Critchley [NF]

What it is: A study of mysticism—defined as an experience, rather than religious practice—by the great British philosopher Critchley, who mines music, poetry, and literature along the way.

Who it's for: Readers of John Gray, Jorge Luis Borges, and Simone Weil. —SMS

Q&A by Adrian Tomine [NF]

What it is: The Japanese American creator of the Optic Nerve comic book series for D&Q, and of many a New Yorker cover, shares his personal history and his creative process in this illustrated unburdening.

Who it’s for: Readers of Tomine’s melancholic, sometimes cringey, and occasionally brutal collections of comics short stories including Summer Blonde, Shortcomings, and Killing and Dying. —NodB

Sonny Boy by Al Pacino [NF]

What it is: Al Pacino's memoir—end of description.

Who it's for: Cinephiles; anyone curious how he's gonna spin fumbling Diane Keaton. —SMS

Seeing Baya by Alice Kaplan [NF]

What it is: The first biography of the enigmatic and largely-forgotten Algerian artist Baya Mahieddine, who first enchanted midcentury Paris as a teenager.

Who it's for: Admirers of Leonora Carrington, Hilma af Klint, Frida Kahlo, and other belatedly-celebrated women painters. —SMS

Absolution by Jeff VanderMeer [F]

What it is: A surprise return to the Area X, the stretch of unforbidding and uncanny coastline in the hit Southern Reach trilogy.

Who it's for: Anyone who's heard this song and got the reference without Googling it. —JHM

The Four Horsemen by Nick Curtola [NF]

What it is: The much-anticipated cookbook from the team behind Brooklyn's hottest restaurant (which also happens to be co-owned by James Murphy of LCD Soundsystem).

Who it's for: Oenophiles; thirty-somethings who live in north Williamsburg (derogatory). —SMS

Seeing Further by Esther Kinsky, tr. Caroline Schmidt [F]

What it's about: An unnamed German woman embarks on the colossal task of reviving a cinema in a small Hungarian village.

Who it's for: Fans of Jenny Erpenbeck; anyone charmed by Cinema Paradiso (not derogatory!). —SMS

Ripcord by Nate Lippens [NF]

What it's about: A novel of class, sex, friendship, and queer intimacy, written in delicious prose and narrated by a gay man adrift in Milwaukee.

Who it's for: Fans of Brontez Purnell, Garth Greenwell, Alexander Chee, and Wayne Koestenbaum. —SMS

The Use of Photography by Annie Ernaux and Marc Marie, tr. Alison L. Strayer [NF]

What it's about: Ernaux's love affair with Marie, a journalist, while she was undergoing treatment for cancer, and their joint project to document their romance.

Who it's for: The Ernaux hive, obviously; readers of Sontag's On Photography and Janet Malcolm's Still Pictures. —SMS

Nora Ephron at the Movies by Ilana Kaplan [NF]

What it is: Kaplan revisits Nora Ephron's cinematic watersheds—Silkwood, Heartburn, When Harry Met Sally, You've Got Mail, and Sleepless in Seattle—in this illustrated book. Have these iconic stories, and Ephron’s humor, weathered more than 40 years?

Who it’s for: Film history buffs who don’t mind a heteronormative HEA; listeners of the Hot and Bothered podcast; your coastal grandma. —NodB

[millions_email]

The Philosophy of Translation by Damion Searls [NF]

What it is: A meditation on the act and art of translation by one of today's most acclaimed practitioners, best known for his translations of Fosse, Proust, et al.

Who it's for: Regular readers of Words Without Borders and Asymptote; professional and amateur literary translators alike. —SMS

Salvage by Dionne Brand

What it is: A penetrating reevaluation of the British literary canon and the tropes once shaped Brand's reading life and sense of self—and Brand’s first major work of nonfiction since her landmark A Map to the Door of No Return.

Who it's for: Readers of Christina Sharpe's Ordinary Notes and Elizabeth Hardwick's Seduction and Betrayal. —SMS

Masquerade by Mike Fu [F]

What it's about: Housesitting for an artist friend in present-day New York, Meadow Liu stumbles on a novel whose author shares his name—the first of many strange, haunting happenings that lead up to the mysterious disappearance of Meadow's friend.

Who it's for: fans of Ed Park and Alexander Chee. —SMS

November

The Beggar Student by Osamu Dazai, tr. Sam Bett [F]

What it is: A novella in the moody vein of Dazai’s acclaimed No Longer Human, following the 30-something “fictional” Dazai into another misadventure spawned from a hubristic spat with a high schooler.

Who it's for: Longtime readers of Dazai, or new fans who discovered the midcentury Japanese novelist via TikTok and the Bungo Stray Dogs anime. —DF

In Thrall by Jane DeLynn [F]

What it is: A landmark lesbian bildungsroman about 16-year-old Lynn's love affair with her English teacher, originally published in 1982.

Who it's for: Fans of Joanna Russ's On Strike Against God and Edmund White's A Boy's Own Story —SMS

Washita Love Child by Douglas Kent Miller [NF]

What it is: The story of Jesse Ed Davis, the Indigenous musician who became on of the most sought after guitarists of the late '60s and '70s, playing alongside B.B. King, Bob Dylan, John Lennon, and more.

Who it's for: readers of music history and/or Indigenous history; fans of Joy Harjo, who wrote the foreword. —SMS

Set My Heart on Fire by Izumi Suzuki, tr. Helen O'Horan [F]

What it is: Gritty, sexy, and wholly rock ’n’ roll, Suzuki’s first novel translated into English (following her story collection, Hit Parade of Tears) follows 20-year-old Izumi navigating life, love, and music in the underground scene in '70s Japan.

Who it's for: Fans of Meiko Kawakami, Ursula K. Le Guin, and Marlowe Granados's Happy Hour. —DF

Didion & Babitz by Lili Anolik [NF]

What it is: A dual portrait of Joan Didion and Eve Babitz, who are so often compared to—and pitted against—each other on the basis of their mutual Los Angeles milieu.

Who it's for: Fans or haters of either writer (the book is fairly pro-Babitz, often at Didion's expense); anyone who has the Lit Hub Didion tote bag. —SMS

The Endless Refrain by David Rowell [NF]

What it's about: How the rise of music streaming, demonitizing of artist revenue, and industry tendency toward nostalgia have laid waste to the musical landscape, and the future of music culture.

Who it's for: Fans of Kyle Chayka, Spence Kornhaber, and Lindsay Zoladz. —SMS

Every Arc Bends Its Radian by Sergio De La Pava [F]

What it is: A mind- and genre-bending detective story set in Cali, Colombia, that blends high-stakes suspense with rigorous philosophy.

Who it's for: Readers of Raymond Chandler, Thomas Pynchon, and Jules Verne. —SMS

Something Close to Nothing by Tom Pyun [F]

What it’s about: At the airport with his white husband Jared, awaiting a flight to Cambodia to meet the surrogate mother carrying their adoptive child-to-be, Korean American Wynn decides parenthood isn't for him, and bad behavior ensues.

Who it’s for: Pyun’s debut is calculated to cut through saccharine depictions of queer parenthood—could pair well with Torrey Peters’s Detransition, Baby. —NodB

Rosenfeld by Maya Kessler [F]

What it is: Kessler's debut—rated R for Rosenfeld—follows one Noa Simmons through the tumultuous and ultimately profound power play that is courting (and having a lot of sex with) the titular older man who soon becomes her boss.

Who it's for: Fans of Sex and the City, Raven Leilani’s Luster, and Coco Mellor’s Cleopatra and Frankenstein. —DF

Lazarus Man by Richard Price [F]

What it is: The former The Wire writer offers yet another astute chronicle of urban life, this time of an ever-changing Harlem.

Who it's for: Fans of Colson Whitehead's Crook Manifesto and Paul Murray's The Bee Sting—and, of course, The Wire. —SMS

Stranger Than Fiction by Edwin Frank [NF]

What it is: An astute curveball of a read on the development and many manifestations of the novel throughout the tumultuous 20th century.

Who it's for: Readers who look at a book's colophon before its title. —JHM

Letters to His Neighbor by Marcel Proust, tr. Lydia Davis

What it is: A collection of Proust’s tormented—and frequently hilarious—letters to his noisy neighbor which, in a diligent translation from Davis, stand the test of time.

Who it's for: Proust lovers; people who live below heavy-steppers. —DF

Context Collapse by Ryan Ruby [NF]

What it is: A self-proclaimed "poem containing a history of poetry," from ancient Greece to the Iowa Workshop, from your favorite literary critic's favorite literary critic.

Who it's for: Anyone who read and admired Ruby's titanic 2022 essay on The Waste Land; lovers of poetry looking for a challenge. —SMS

How Sondheim Can Change Your Life by Richard Schoch [NF]

What it's about: Drama professor Schoch's tribute to Stephen Sondheim and the life lessons to be gleaned from his music.

Who it's for: Sondheim heads, former theater kids, end of list. —SMS

The Serviceberry by Robin Wall Kimmerer [NF]

What it is: 2022 MacArthur fellow and botanist Kimmerer, an enrolled member of the Citizen Potawatomi Nation, (re)introduces audiences to a flowering, fruiting native plant beloved of foragers and gardeners.

Who it’s for: The restoration ecologist in your life, along with anyone who loved Braiding Sweetgrass and needs a nature-themed holiday gift. —NodB

My Heart Belongs in an Empty Big Mac Container Buried Beneath the Ocean Floor by Homeless [F]

What it is: A pseudonymous, tenderly comic novel of blue whales and Golden Arches, mental illness and recovery.

Who it's for: Anyone who finds Thomas Pynchon a bit too staid. —JHM

Yoke and Feather by Jessie van Eerden [NF]

What it's about: Van Eerden's braided essays explore the "everyday sacred" to tease out connections between ancient myth and contemporary life.

Who it's for: Readers of Courtney Zoffness's Spilt Milk and Jeanna Kadlec's Heretic. —SMS

Camp Jeff by Tova Reich [F]

What it's about: A "reeducation" center for sex pests in the Catskills, founded by one Jeffery Epstein (no, not that one), where the dual phenomena of #MeToo and therapyspeak collide.

Who it's for: Fans of Philip Roth and Nathan Englander; cancel culture skeptics. —SMS

Selected Amazon Reviews by Kevin Killian [NF]

What it is: A collection of 16 years of Killian’s funniest, wittiest, and most poetic Amazon reviews, the sheer number of which helped him earn the rarefied “Top 100” and “Hall of Fame” status on the site.

Who it's for: Fans of Wayne Koestenbaum and Dodie Bellamy, who wrote introduction and afterword, respectively; people who actually leave Amazon reviews. —DF

Cher by Cher [NF]

What it is: The first in a two-volume memoir, telling the story of Cher's early life and ascendent career as only she can tell it.

Who it's for: Anyone looking to fill the My Name Is Barbra–sized hole in their heart, or looking for something to tide them over until the Liza memoir drops. —SMS

The City and Its Uncertain Walls by Haruki Murakami, tr. Philip Gabriel [F]

What it is: Murakami’s first novel in over six years returns to the high-walled city from his 1985 story "Hard-Boiled Wonderland and the End of the World" with one man's search for his lost love—and, simultaneously, an ode to libraries and literature itself.

Who it's for: Murakami fans who have long awaited his return to fiction. —DF

American Bulk by Emily Mester [NF]

What it's about: Reflecting on what it means to "live life to the fullest," Mester explores the cultural and personal impacts of America’s culture of overconsumption, from Costco hauls to hoarding to diet culture—oh my!

Who it's for: Lovers of sustainability; haters of excess; skeptics of the title essay of Becca Rothfeld's All Things Are Too Small. —DF

The Icon and the Idealist by Stephanie Gorton [NF]

What it is: A compelling look at the rivalry between Margaret Sanger, of Planned Parenthood fame, and Mary Ware Dennett, who each held radically different visions for the future of birth control.

Who it's for: Readers of Amy Sohn's The Man Who Hated Women and Katherine Turk's The Women of NOW; anyone interested in the history of reproductive rights. —SMS

December

Rental House by Weike Wang [F]

What it's about: Married college sweethearts invite their drastically different families on a Cape Code vacation, raising questions about marriage, intimacy, and kinship.

Who it's for: Fans of Wang's trademark wit and sly humor (see: Joan Is Okay and Chemistry); anyone with an in-law problem.

Woo Woo by Ella Baxter [F]

What it's about: A neurotic conceptual artist loses her shit in the months leading up to an exhibition that she hopes will be her big breakout, poking fun at the tropes of the "art monster" and the "woman of the verge" in one fell, stylish swoop.

Who it's for: Readers of Sheena Patel's I'm a Fan and Chris Kraus's I Love Dick; any woman who is grateful to but now also sort of begrudges Jenny Offil for introducing "art monster" into the lexicon (me). —SMS

Berlin Atomized by Julia Kornberg, tr. Jack Rockwell and Julia Kornberg [F]

What it's about: Spanning 2001 to 2034, three Jewish and downwardly mobile siblings come of age in various corners of the world against the backdrop of global crisis.

Who it's for: Fans of Catherine Lacey's Biography of X and Joshua Cohen's The Netanyahus. —SMS

Sand-Catcher by Omar Khalifah, tr. Barbara Romaine [F]

What it is: A suspenseful, dark satire of memory and nation, in which four young Palestinian journalists at a Jordanian newspaper are assigned to interview an elderly witness to the Nakba, the violent 1948 expulsion of native Palestinians from Israel—but to their surprise, the survivor doesn’t want to rehash his trauma for the media.

Who it’s for: Anyone looking insight—tinged with grim humor—into the years leading up to the present political crisis in the Middle East and the decades-long goal of Palestinian autonomy. —NodB

The Shutouts by Gabrielle Korn [F]

What it's about: In the dystopian future, mysteriously connected women fight to survive on the margins of society amid worsening climate collapse.

Who it's for: Fans of Korn's Yours for the Taking, which takes place in the same universe; readers of Becky Chambers and queer-inflected sci-fi. —SMS

What in Me Is Dark by Orlando Reade [NF]

What it's about: The enduring, evolving influence of Milton's Paradise Lost on political history—and particularly on the work of 12 revolutionary readers, including Malcom X and Hannah Arendt.

Who it's for: English majors and fans of Ryan Ruby and Sarah Bakewell—but I repeat myself. —SMS

The Afterlife Is Letting Go by Brandon Shimoda [NF]

What it's about: Shimoda researches the mass incarceration of Japanese Americans during WWII, and speaks with descendants of those imprisoned, for this essay collection about the “afterlife” of cruelty and xenophobia in the U.S.

Who it’s for: Anyone to ever visit a monument, museum, or designated site of hallowed ground where traumatic events have taken place. —NodB

No Place to Bury the Dead by Karina Sainz Borgo, tr. Elizabeth Bryer [F]

What it's about: When Angustias Romero loses both her children while fleeing a mysterious disease in her unnamed Latin American country, she finds herself in a surreal, purgatorial borderland where she's soon caught in a power struggle.

Who it's for: Fans of Maríana Enriquez and Mohsin Hamid. —SMS

The Rest Is Silence by Augusto Monterroso, tr. Aaron Kerner [F]

What it is: The author of some of the shortest, and tightest, stories in Latin American literature goes long with a metafictional skewering of literary criticism in his only novel.

Who it's for: Anyone who prefers the term "palm-of-the-hand stories" to "flash fiction." —JHM

Tali Girls by Siamak Herawi, tr. Sara Khalili [F]

What it is: An intimate, harrowing, and vital look at the lives of girls and women in an Afghan mountain village under Taliban rule, based on true stories.

Who it's for: Readers of Nadia Hashimi, Akwaeke Emezi, and Maria Stepanova. —SMS

Sun City by Tove Jansson, tr. Thomas Teal [F]

What it's about: During her travels through the U.S. in the 1970s, Jansson became interested in the retirement home as a peculiarly American institution—here, she imagines the tightly knit community within one of them.

Who it's for: Fans of Jansson's other fiction for adults, much of which explores the lives of elderly folks; anyone who watched that documentary about The Villages in Florida. —SMS

Editor's note: We're always looking to make our seasonal book previews more useful to the readers, writers, and critics they're meant to serve. Got an idea for how we can improve our coverage? Tell me about it at sophia@themillions.com.

[millions_email]

Three Authors in Search of Melville

When, back in the 1930s, novelist Jean Giono set about working on the first French translation of Moby-Dick, he and his collaborator Lucien Jacques were mulling over approaches to the project when their ideal methodology suddenly appeared before them like a revelation. “The matter was settled,” Giono explains, “when we realized that Melville himself was handing us the principles that would guide our work. ‘There are some enterprises,’ he says, ‘in which a careful disorderliness is the true method.’” This statement of purpose both matched their own sensibility and fit the character of Melville’s text; from there on out, the work was all smooth sailing. “Everything seemed to be settled in advance,” Giono recounts, “and there was nothing left to do but let things take their course.”

This careful disorderliness which Giono and Jacques found in Moby-Dick is, as has been often remarked, one of the book’s central features. In his 1947 study of Melville, Call Me Ishmael, Charles Olson explains that Moby-Dick “was two books written between February, 1850 and August, 1851. The first book did not contain Ahab. It may not, except incidentally, have contained Moby-Dick.” Olson’s point is that between an early, nearly completed version of the book and the final volume, Melville, fueled by his intensive reading of Shakespeare, was given the tools to rewrite the work entirely, now replete with “madness, villainy, and evil.” But the multiplicity of Moby-Dick goes well beyond the initial voyage-of-a-whaler framework coupled with the Ahab story. What makes the book so perpetually thrilling is as much the hybrid nature of the work, a “disorderliness” that takes in disquisitions on the finer points of whaling, dramatic monologues, and polyphonic collages of voices, as it is the mad captain’s metaphysical quest.

This methodical messiness, though, is not only the guiding principle of Moby-Dick and of Giono and Jacques’s translation of that novel. It is also the springboard for any number of works that take Melville’s life and writing as their subject. In both critical studies like Olson’s and more imaginative works of fiction, writers who have made it their business to struggle with Melville’s legacy have often taken hybridity as their method. It’s as if the example of Moby-Dick has freed them from the constraints of a simple monolithic approach, whether that be a linear narrative or a straightforward work of criticism.

One of the first of these odd reckonings with Melville remains among the oddest. After Giono and Jacques completed their translation of Moby-Dick, their publisher asked Giono to contribute a preface. Instead, he ended up writing a new book altogether, Melville: A Novel, a fictional account of the author’s life which was issued as a separate volume (and is now being reprinted in a new English translation by New York Review Books). In this short work, originally published in 1941, Giono follows a largely ahistorical Melville as he takes a trip to London to deliver his latest book, White-Jacket, to his publisher. Left with two weeks to kill in the dreary English capital, Melville instead departs for the countryside, where he is constantly hounded by an angel that appears to him and goads him on to write a real book, which is to say Moby-Dick.

Melville is helped along in this goal by the appearance of a beautiful woman, the completely fabricated Adelina White, with whom he shares a mail-coach and carries on a chaste affair. As they ride through the countryside, Melville puts into words the landscapes they pass for Adelina’s benefit, and through his poetic voice, makes nature immediate for his companion in a way it hasn’t been before. This is some romantic stuff to be sure, and Giono goes all in on the power of the poet (Melville) to transform reality: “He made her come to life, no longer as a woman sitting beside a man on the top deck of the Bristol Mail, but as an absolute ruler of the weathers: he had made her come alive in her own domain.”

This exalted view of Melville’s poetic mission is one that Giono emphasizes throughout the work, both in lyrical narrative passages like the woodland jaunt and in more reflective moments in which Melville’s angel appears as a stand-in in for the author’s own conflicted feelings about his literary mission. But what makes Giono’s book such an enjoyable read is the wide range of other modes that he employs and which grant the work a richness and scope that pay ample tribute to the book it references. Among the memorable passages are humorous set pieces (as when Melville goes to a second-hand shop to outfit himself for his country outing), odd surreal details (a crown of thorns that the young writer puts on and that leaves a tiny part of his head perpetually soft and sticky), and interpolated bits of literary criticism. Giono adopts this last mode in particular to wax poetic on the American literary project. “[Melville is] an American democrat,” he writes. “He’s part of that democracy whose praises Whitman will sing later on, starting with the second poem in his Leaves of Grass.”

Easy enough for a French writer (especially one with a romantic turn of mind) to be enamored of American democracy and the literature it produces. Sometimes, though, it takes a native to bring a more critical eye to the proceedings. In Call Me Ishmael, his study, Olson takes up the challenge. Rather than conflating Melville and Whitman as Giono does, he pointedly differentiates the two. “Whitman we have called our greatest voice because he gave us hope,” he writes. “Melville is the truer man. He lived intensely his people’s wrong, their guilt.” In fact, Olson’s critical study is filled throughout with reflections on Melville’s conflicted take on the American project. Alongside the positive example of the Pequod, that democratic microcosm of the country, Olson shows us, sit the brute economic facts of the voyage as well as the understanding that the men’s mission is to overtake and destroy nature.

In presenting his reading of Melville’s life and work, Olson organizes his chapters into neat thematic sections, but he then complicates this orderliness by drawing on any number of outside texts and prose styles. Alternating intensive critical analysis with anecdote and interpolation, switching up academic prose with neat poetical formulation, Olson achieves a carefully controlled disorderliness that enriches our understanding of his subject. If part of Olson’s project is to analyze Ahab’s monomaniacal quest to conquer space, then Olson, like Melville before him, counters with a polyphonic range of voices and approaches that shows up that quest for the narrow gesture that it is.

For all their hybrid gestures, though, Giono’s book is essentially a novel, while Olson’s work is clearly a critical study. It took the work of another writer, the American Paul Metcalf, to strike a middle ground between the two genres. In his 1965 book, Genoa, Metcalf, who was Melville’s great grandson, makes his ancestor’s words the very engine of the narrative. Largely plotless, the book follows Michael Mills, non-practicing doctor, as he holes up in his attic while his wife is off at work, obsessively poring over the collected works of Melville, as well as writings about Christopher Columbus and anatomy textbooks. Ever since, as a child, he and his brother, Carl, discovered an old copy of Typee while playing in a haunted house, he’s been obsessed by the writer, and his mind is trained to dial up an appropriate quotation from Melville for every situation he encounters.

Michael’s mind, in fact, is where most of the action takes place in Genoa, and Metcalf makes us privy to the workings of that consciousness as we follow along with him in his attic. Michael’s critical musings, which often range intertextually between all his various sources, are both enlightening and dangerously obsessive. In one passage, Michael will expertly compare Columbus and Melville, outlining the ways in which both the explorer’s decision to go west instead of to Africa and Melville’s decision to send Ahab east instead of on the customary westward voyage “did more violence, perhaps, than all the wars that followed” simply by their geographic dislocations. But then the obsessiveness will take over and he’ll mash all his texts together in a way that seems more maddening than instructive, as when he compares Ahab’s quest for the whale with not only Columbus’s quest for land but with a sperm’s journey towards the egg.

Hovering over everything that Michael does is the memory of his brother. Carl, whose story takes over the narrative in the book’s second half, lived an adventurous life, which culminated first in his being the victim of war crimes in China and his kidnapping and murdering a child back stateside, a crime which led to his execution. By the time we learn the details of Carl’s life, though, Metcalf has fully instructed us in the bloody history of the United States, dating back to the introduction of Europeans to the western hemisphere and carrying on through America’s new manifest destiny of nautical imperialism. Thus, when Michael narrates his brother’s murderous pursuits, we’ve already been given a larger context in which to understand them. If at first the connection between all these threads is simply implied, Michael eventually makes them explicit. “Perhaps like Ishmael on board the Pequod,” he muses, “[Carl] was hunting back toward the beginnings of things; and, like the voyage of the Pequod—or of any of the various caravels of Columbus that stuck fierce weather returning from the Indies—perhaps Carl’s eastward voyage, his voyage ‘home’, was disastrous.”

Presiding over these musings, though, is a critical figure and authorial stand-in who cuts a more-or-less ridiculous figure. A doctor who refuses to practice, a man hobbled by a troublesome club-foot, Michael neglects his household duties to pore uselessly over his texts. He is powerless to maintain order in his own home as his kids run amok while he hides in the attic. If Olson represents the stable, authoritative critic, then Michael Mills is a far more doubtful one, highly intelligent and knowledgeable about his material, but cursed by an immoderate mind that makes his conclusions less than trustworthy. As do Giono and Olson, Metcalf allows his narrator’s fevered brain plenty of space in which to operate, but, by making him an essentially absurd individual, Metcalf pointedly undercuts his authority. If Michael’s occasionally stirring insights mark Genoa as a valuable work of criticism, then the framing of those insights as coming from a highly dubious character make it just as much an expert work of fiction. So too with Melville: A Novel, which combines a personalized reading of its subject’s oeuvre with an imaginative account of his life, even if here the author’s concerns tip far more towards the fanciful.

Image: Wikimedia

The Author Sends Her Regrets: J.K. Rowling and Other Writers with Second Thoughts

Recently J.K. Rowling dropped a bombshell on the smoking remnants of one of the fiercest shipping wars of the last decade: “I wrote the Hermione/Ron relationship as a form of wish fulfillment. That’s how it was conceived, really. For reasons that have very little to do with literature and far more to do with me clinging to the plot as I first imagined it, Hermione ended up with Ron.” It’s from an interview conducted by Hermione herself, Emma Watson, excerpted in the Sunday Times; the full article, in an issue of Wonderland Magazine guest-edited by Watson, came out on Friday. (The words “publicity stunt” may be floating around, but that kind of speculation is useless.) The ladies, bafflingly, “agree[d] that Harry and Hermione were a better match than Ron and Hermione,” Ron wouldn’t be able to satisfy Hermione’s needs, and the pair as she wrote them would need relationship counseling. And then the internet exploded.

OK, first of all, JKR, please just stop. Is the most aggravating thing about all of this the fact that Hermione doesn’t belong with either of these jokers? Was there literally anyone else for her to get with? (Rowling’s shoddy math suggests possibly not; despite the insistence in an early interview that “there are about a thousand students at Hogwarts,” there remain just eight Gryffindors in the matriculating class of ’98, suggesting no more than three dozen in the entire year, a whole house of which remain irredeemably, mustache-twirlingly evil despite seven books in which to write convincing moral ambivalence and complexity. But I digress.)

But also, JKR, please just stop — for reasons that have a lot to do with literature. Because the weirdest thing about the statement is the “wish fulfillment” bit, which I’ve seen interpreted many different ways, none of them satisfactory. My read of it is accompanied by this question: how is a writer setting down a plot from her head wish fulfillment? Forced, sure — this certainly wasn’t the only instance where it seemed that Rowling was stifled by the tyranny of the outline she mapped out more than a decade before penning The Deathly Hallows. (I spent years wondering how the hell the final word would, as promised, be “scar,” though by the time I got to the last page of the epilogue I was too infuriated to care.)

This isn’t the first time that Rowling has “revealed” further details about her characters, as if she is their publicist rather than their creator. The Dumbledore announcement was, admittedly, totally awesome, for the political ramifications at the very least. But Rowling seems insistent on undercutting her authorial intent, or her position as omniscient narrator, the sort of “I would have loved for this to happen” statement, it’s like, really? I was under the impression that you were making all the things happen. (The full article in Wonderland—or the full interview, excerpted at Mugglenet — is worth a read for its continued, almost amplified strangeness — Rowling speaks of being shocked to see the filmmakers depicting things she hadn’t written but was feeling about the characters, like the scene between Harry and Hermione in the tent in the first installment of The Deathly Hallows. “Yes, but David and Steve — they felt what I felt when writing it,” Rowling tells Watson, referring to the director and screenwriter. “That is so strange,” Watson responds. Yes — this whole thing is so strange. It feels like there’s a simultaneous disregard for the concept of subtext and the idea that the characters were driven by something other than Rowling’s own fingers. “JKR, I think, probably is still in mystical mode when talking about her characters and work,” Connor Joel said to me in a Twitter conversation. “Which can be OK...sometimes.”)

Is a writer allowed to have regrets? Certainly. Is she allowed to air them publicly? I mean, yeah, it’s a free internet, why not? Do I want to hear a single additional word about the world of Harry Potter from J. K. Rowling that is not in the form of another book? Unless she is going to travel via Time-Turner to the past and personally validate all of my ships, no, not particularly — though that’s just me. (On second thought, no, not even that: sometimes the joy of delving into subtext is that it remains, well, sub.) The night all this came out (my new BFF) Anne Jamison kicked off a round of hilarious authorial regrets on Twitter, collected here. (For example: “‘I realize I made generations believe instant antipathy is a valid basis for ideal marriage,’ sighed Ms Austen, ‘I just thought he was hot.’”)

All joking aside, these tweets got me thinking: how often has this sort of thing happened in the past? Is there something fundamental in the author/reader relationship that feels like it’s being abused in Rowling’s admissions — or is she just following a long tradition of regretful writers undermining their own authority via statements after publication? Initial research suggests that some of the most famous writers haven’t stayed as faithful to their own original texts as I might have guessed. I mean, these examples aren’t exactly the same (I can hear you saying this, even now!), and that might get at what feels so incredibly strange about the “wish fulfillment” idea that Rowling’s putting forth. But regrets are regrets, and once the pages are printed — and even with all the revisions and retractions in the world — there’s essentially no going back. Here are five authors who had a variety of regrets and later said they really wished they’d done things differently — and, in many cases, went on to try to actually do things differently, to varying degrees of success:

Charles Dickens

Image via Wikimedia Commons

Oliver Twist’s greedy, villainous employer, Fagin, is most famously marked by his Jewishness, via every derogatory stereotype in the history of man and by outright assertion: references as “the Jew” outnumber “the old man” in the original text nearly ten-to-one. There was no doubt in Dickens’s mind, nor that of many of his mid-Victorian counterparts, that this was totally fine, that Fagin’s crimes fell right in line with his background: he stated later, by way of (really poor and blatantly anti-Semitic) defense, that “that class of criminal almost invariably was a Jew.” But in 1860 Dickens sold his house to a Jewish couple and befriended the wife, Eliza, who wrote him later to say that the creation of Fagin was a “great wrong” to the Jewish people. Dickens saw the light, albeit in a sort of, “Well, some of my best friends are Jewish!” sort of way, and began stripping out references to Fagin’s religion from the text, as well as the caricature-like aspects: at a reading of a later version, it was observed that, “There is no nasal intonation; a bent back but no shoulder-shrug: the conventional attributes are omitted.” But was it too little too late? After all, the original depiction of Fagin has endured through the centuries. Dickens tried, anyway. “There is nothing but good will left between me and a People for whom I have a real regard,” he wrote. “And to whom I would not willfully have given an offence.”

Herman Melville

Image via Wikimedia Commons

Typee, Melville’s first novel and the most popular during his lifetime, is described as “one of American culture’s more startling instances of a fluid text.” There appears to be no definitive version of Typee — the sort of book that makes you question just how definitive anything you read really is. “All texts are fluid,” writes John Bryant, a scholar who’s done extensive work on Typee, examining its states of flux. “They only appear to be stable because the accidents of human action, time and economy have conspired to freeze the energy they represent into fixed packets of language.” Some of the changes — which were made over the course of half a century, from the first drafts Melville penned fresh off the high seas to the final years of his life — came from pressures from critics and his publishers: disparagement of missionary culture, expanded upon in first drafts, was largely removed in subsequent editions. Some requests for changes, including a toning down of the ‘bawdiness’ of earlier editions, took place decades later, when Melville was an old man — “Certain passages were to be restored, a paragraph on seaman debauchery dropped, and ‘Buggery Island’ changed to ‘Desolation Island,’” writes Bryant, though not all of these changes were honored in the posthumous edition. Bryant has developed a digital edition to view the fluid text as a whole, though perhaps even that can’t — and shouldn’t — answer the question of whether one version or another can be called the definitive text.

F. Scott Fitzgerald

Image via Wikimedia Commons

F. Scott Fitzgerald, a man prone to last-minute editorial regrets: he sent a telegram to his publisher as The Great Gatsby was going to press, asking to change the title to Under the Red, White, and Blue. It arrived too late. He’d wavered so much on the title already — amongst a dozen other suggestions, he’d been set on Trimalchio in West Egg for a good while. But Tender is the Night suffered, in his opinion, from problems far larger than what was printed on the dust jacket. It was published in 1934 to poor critical and public response, and Fitzgerald set to work figuring out why it didn’t work. When it was reprinted two years later, he wanted to make minor changes and clarifications, and wrote that, “sometimes by a single word change one can throw a new emphasis or give a new value to the exact same scene or setting.” But he soon decided it wasn’t a “single word” — it was the entire structure: “If pages 151-212 were taken from their present place and put at the start,” he wrote to his editor at Scribner, “the improvement in appeal would be enormous.” He set to work slicing apart the novel — physically — and rearranging it in the order he felt it was now meant to be, the narrative now chronological rather than reliant on flashback. The copy is on display at Princeton, with Fitzgerald’s penciled note written inside the front cover: “This is the final version of the book as I would like it.” After Fitzgerald’s death, Malcolm Cowley decided to try to fulfill these editorial wishes, rearranging the book based on the notes and cut-up version. But people weren’t any more interested in this version than the first, and in the intervening half-century, the original has endured.

Ray Bradbury

Image via Wikimedia Commons

If the biggest disappointment of 2015 will be the fact that almost nothing resembles the 2015 bits of “Back to the Future” (what’s sadder — no hoverboards or no magical pizzas?), it speaks to the risks of setting a sci-fi novel in the not-so-distant future. When Bradbury’s The Martian Chronicles, first published in 1947, were reissued fifty years later, the stories’ chronological start date was just two years away. Bradbury and his publisher made the call to bump up the timeline by three decades, 2030-2057, and made some additional editorial changes while they were at it. The timeline shift isn’t unique in science fiction: Wikipedia’s got a poetically-titled “List of stories set in a future now past,” which reveals that Philip K. Dick’s Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep also got a thirty-year bump. It’s an interesting question, and one that may crop up more and more as time goes on: does reading about some sort of alien “future” that’s now a few years in the past take a reader right out of the story? Isn’t there some joy in imagining Bradbury imagining 1999 in 1947, a vision of the future from that precise point in the past?

Anthony Burgess

Image via erokism/Flickr

And then what to do if an author wishes the entire book had never been written? One famous example: “J.D. Salinger spent 10 years writing The Catcher in the Rye and the rest of his life regretting it,” Shane Salerno and David Shields assert in their recent biography. But Salinger’s dissatisfaction appeared to stem from the extraordinary amount of unwanted attention he received for it over the years. But what about Anthony Burgess, who wrote about A Clockwork Orange in his Flame into Being: The Life and Work of D. H. Lawrence, published in 1985:

We all suffer from the popular desire to make the known notorious. The book I am best known for, or only known for, is a novel I am prepared to repudiate: written a quarter of a century ago, a jeu d’esprit knocked off for money in three weeks, it became known as the raw material for a film which seemed to glorify sex and violence. The film made it easy for readers of the book to misunderstand what it was about, and the misunderstanding will pursue me until I die. I should not have written the book because of this danger of misinterpretation, and the same may be said of Lawrence and Lady Chatterley’s Lover.

Lawrence died decades before the obscenity trials placed his book at the center of the moral questions of literature and society. Burgess had decades to witness the unraveling of the “misunderstandings” of the novel he will always be most remembered for. As for its merits as a work of literature? He also described it as “too didactic to be artistic.” Ah, well. Everyone is entitled to their opinions of a book and its characters. Even, I suppose, the author himself.

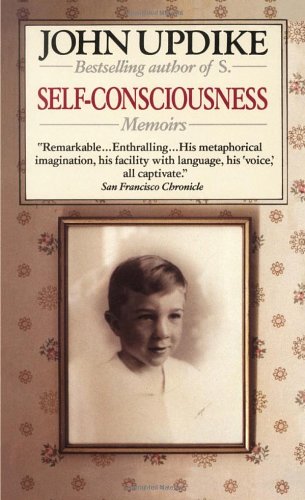

John Updike, and the Curious Business of Sustaining Literary Reputations

Toward the end of his life, John Updike was fond of musing about how little the world would note his passing. He suspected that “a shrug and tearless eyes / will greet my overdue demise; / The wide response will be, I know, / ‘I thought he died a while ago.’”

The John Updike Society, which held its first conference last month, is dedicated to proving the author wrong. The event, held near Updike’s hometown of Shillington, Pennsylvania, started the society’s work of sustaining and growing a literary reputation. The weekend included academic readings, panels of friends and family, and tours of the author’s two boyhood homes and the environs of Shillington and Reading where much of his fiction was set. The mission of the Society -- along with creating opportunities to enjoy the fellowship of Updike devotees – is “awakening and sustaining reader interest in the literature and life of John Updike.”

No detail was too small for discussion. Attendees wanted to know if Updike did the dishes at home, whether he liked Sinatra, if he was handy around the house. On bus tours, attendees pondered the department store where his mother worked, the restaurant where he’d lunched as teenager, the old movie theater featured in his non-fiction.

Much of the attendees’ interest, understandably, focused on discovering if their idol was indeed the man they knew.

During the testimony of family and friends, Updike held up pretty well. He was described by classmates as bookish, popular and enduringly responsive; by his children as a present if occasionally distracted father; and by his first wife Mary Weatherall as an author who valued his spouse’s opinion. There were a couple of surprises – he might not have written as many words each day as he claimed and according to his children, he inexplicably struggled to connect with his father, Wesley, a man Updike’s children seemed to adore.

Then of course there were the conference papers, all intended to continue the critical discussion that will be so important to sustaining the Updike reputation long-term.

“Can an author survive without authorial champions?” Society President James Plath asked when I interviewed him after the conference. “I don’t think so.”

The evidence supports his claim. In one of his last interviews, in October 2008, Updike cited the curious case of Emily Dickinson, who was not well known upon her death and who required the help of critics decades down the road to lift her to her current place in the canon. “There is a whole raft of poets contemporary with Emily Dickinson,” Updike said. “None of them would have imagined that she would have become one of the defining names of American letters.”

The most famous of the exhumed luminaries -- the example often cited to convey the cruelties of literary reputation -- is Herman Melville, who died at age 72 in relative anonymity after several literary disappointments and 19 years working in a customs house. His obituary in 1891 in the New York Times looked, in its entirety, like this:

Herman Melville died yesterday at his residence, 104 East 26th Street, this city, or heart disease, aged seventy-two. He was the writer of Typee, Omoo, Mobie Dick, and other sea-faring tales, written in earlier years. He leaves a wife and two daughters, Mrs. M. B. Thomas and Miss Melville.

Bummer. Melville apparently was the deceased writer Updike worried he would become -- dead before he‘d died.

It took 30 years for what is now called the Melville Revival to commence and for Melville to ascend to his rightful place in the American canon. This was accomplished by the only people capable of doing it -- scholars, historians, writers, publishers. In Melville’s case, it was biographers Raymond Weaver and Carl Van Doren and author and critic D.H. Lawrence. Without them, Melville’s historical significance might have diminished beyond even the four lines devoted to him in the Times obituary.

Updike seemed to understand as much. In that late 2008 interview, he said literary reputations are “strange things,” left often to the whims and tastes of future generations. He noted that 19th century readers were often concerned with order, meter, and plots in which good triumphs over evil – qualities less important to today’s modern and postmodern readers. He lauded Norman Mailer for not pushing too hard in his lifetime on behalf of his literary reputation, since it was an issue largely beyond his control.

Society President Plath, of course, likes Updike’s odds. He suspects future scholars will be wondrous of Updike’s capacity with metaphor, happy to find his descriptions of sex, thrilled at the number of other texts that Updike works off of in his oeuvre -- including three novels written in homage to Hawthorne’s The Scarlet Letter. “I think he’s in pretty good shape,” Plath says.

Updike’s sometimes editor at the New Yorker, Charles McGrath, also liked Updike’s odds of enduring. During that late interview with Updike, he said, “If those of us in this room had to bet who would last, you’d put your money on Bellow, Updike, and Roth.”

And yet Updike knew even he could be forgotten. There was the fear, very real, Updike thought, that reading of any kind might wither away, as well as the possibility that future generations will not be concerned with the perspective of a white, middle-class male from the Mid-Atlantic region who wrote primarily in a realistic mode. He said:

These piles of books that all of us writer are piling up [could] become just as burdensome as Latin writing in the Renaissance. There was a lot of that, and who reads it now except a few scholars? So, yes, it’s not something you should stay awake at night about, you should, my theory is, do your best, try to be honest, in your work, and amusing…. Beyond that it is out of your control

And, on a weekend devoted to John Updike, there were signs of the struggle to endure any author faces. His children, though admiring and laudatory of their father’s work, admitted to not always getting through it – daughter Miranda has tried to read Couples a few times. Daughter Elizabeth Cobblah said her father had decades ago suggested she read his African novel, The Coup, in anticipation of her marrying a man from Ghana. She hasn’t yet gotten around to it, but she plans to.

Trouble also lurked in the center of the Updike universe, the Shillington house where he grew up, and which he lovingly described in short stories, novels, and his memoirs, Self-Consciousness. The house is now occupied by the advertising agency Niemczyk/Hoffman, whose employees graciously allowed the Society members to tour their offices. In one room, formerly the guest bedroom where Updike watched his mother write fiction, the agency’s principal, Tracy Hoffman, was asked by a Society member if he read Updike.

“I’ve tried, but the descriptions …” Hoffman said, his voice trailing off, suggesting the descriptions were … um … too much.

“Have you tried Pigeon Feathers?” the Society member asked.

“I did,” Hoffman said, wincing.

In his memoirs, Updike said, that one of his great lifetime joys was watching the world going on without him, “ the awareness of things going by, impinging on my consciousness, and then, all beyond my control, sliding away toward their own destination and destiny.”

In that respect, too, Updike might have been gratified by this first weekend held in his honor – the world, as he suspected, will continue to roll on happily both with and without him.

On Ambition, Cocktail Party Invitations, and the “Bizarre Compulsion” to Write

Recently there's been a ruckus regarding the blatant pursuit of literary fame, especially where the n+1 editors are concerned. In the current issue of Poetry, Adam Kirsch plumbs the depths of literary ambition and the desire for personal recognition, and classifies Keith Gessen's All The Sad Young Literary Men as "a chemically pure example of the kind of literary ambition that has less to do with wanting to write well than with wanting to be known as a writer." Kirsch uses Gessen's blatant ambition, both the theme and the generating force behind his novel, as the springboard to consider the writer's desire for acknowledgement. While Kirsch criticizes Gessen's "naive directness," it becomes obvious that if Gessen's work is a vehicle for recognition and status, he has done well for himself. Not only was Gessen lauded at the National Book Foundation's 5 Under 35 soiree recently and a co-host of the New New York Intellectual series at the New School, but he continues to write for esteemed periodicals like the New York and London Review of Books and receive acknowledgement, if not praise, from established critics, Kirsch included. Gessen is certainly not the first writer to wear his ambitions on his sleeve. He follows in a long line of writers, including Laurence Sterne. Sterne claimed he wrote Tristram Shandy, "not to be fed, but to be famous." And become famous he did. Not only did he have a race horse and a country dance named after his novel, but he became a celebrity. His popularity did not wane with the less favorable reviews of the later portions of his serialized work, because, according to the Columbia History of the British Novel, his fans "wanted not just the book but the man behind the book (one reader said ‘I'd ride fifty miles just to smoke a pipe with him')." Perhaps if Gessen were more honest about his ambitions, we could find something humorous, or at least endearing, in it all. Perhaps then his readers would write in that they'd want to have a smoke with him too.And yet, despite all odds, there are the writers who seem indifferent to fame. Edward P. Jones is one of those. In his essay, "We Tell Stories," he divides writers into two groups: those who aspire to "be invited to a lifetime of cocktail parties" and those who write because of some "bizarre compulsion." If Gessen falls into the first group, Jones (by his own admission) falls into the second. This was apparent on Thursday evening, when Jones read from an enclave on Tenth Street known as the Lillian Vernon Creative Writers House, in what by appearances was once a living room, replete with a fireplace and mantel, a multi-paned front window, and a crowd of attentive readers sitting on folding chairs. From his second book of short stories, All Aunt Hagar's Children, Jones read about temptation (in the form of the Devil himself, appearing at a Safeway off Good Hope Road) and transformation (going blind, literally, in the blink of an eye).In person, Jones is humble and unassuming, and he sounds calm and wise, if not quite comfortable speaking in front of a large audience. His voice came alive when reading the scene from the bus in "Blindsided," where Roxanne first goes blind, a scene that deftly combines compassion, humor and desperation. One senses that Jones's imaginative generosity would be constrained if he paid more mind to increasing his literary status than developing his characters and telling their stories. While speaking about writing The Known World, he posits that if he'd read forty books to research his novel as he'd initially planned, "the characters may have taken a back seat." And this, to Jones as well as to his readers, would have been detrimental, because "the research doesn't matter if the characters aren't there."Jones's humility and lack of ambition were enough to make the man sitting next to me comment in disbelief. Perhaps it is precisely this long gestation - Jones's long periods spent growing and developing his characters - his willingness to stand back, and his lack of desire to conquer literary heights that has made his work so remarkable and the lives of his characters, even in his short stories, stretch far beyond, one feels, the pages they're written on. While Jones hinted at currently searching for new characters, the only thing he admitted to working on was "getting back to Washington in one piece." He spoke a few times of a woman in the desert, as if he's tilling and planting the seeds for his next crop. We can wait.Jones tramples the idea of literary celebrity. If Gessen worships at the altar of literature, and through writing hopes to elevate himself, Jones hopes to deflate such notions of becoming a literary chosen one. To Jones, writing is an act of compassion and communication, and his process not so different from any other task: "And we are not noble, just human. We get up to our day, however wonderful, however horrible, as they have been doing since there were white blank pages, before the blank computer screen, when there were only grunts and hand gestures, and we tell stories."Besides, good writing is timeless, and literary celebrity is often short-lived. There is backlash, capricious fashion, and the the vicissitudes of time. The quest for literary renown isn't new, nor is praise from the literary world consistent. A little article entitled "Literary Fame," appearing in the Buffalo Courier and reprinted in the November 12, 1890, New York Times, speaks of fleeting fame, specifically Herman Melville's, and how easily one can slip from favor. A year before Melville's death, so little was said of him that most people already thought him dead:Forty-four years ago, when [Herman Melville's] most famous tale, "Typee," appeared, there was not a better known author than he, and he commanded his own prices. Publishers sought him, and editors considered themselves fortunate to secure his name as a literary star. And to-day! Busy New York has no idea he is even alive, and one of the best-informed literary men in the country laughed recently at me statement that Herman Melville was his neighbor by only two blocks. "Nonsense!" said he. "Why, Melville's dead these many years!" Talk about literary fame! There's a sample of it.