Mentioned in:

Most Anticipated: The Great Winter 2025 Preview

It's cold, it's grey, its bleak—but winter, at the very least, brings with it a glut of anticipation-inducing books. Here you’ll find nearly 100 titles that we’re excited to cozy up with this season. Some we’ve already read in galley form; others we’re simply eager to devour based on their authors, subjects, or blurbs. We'd love for you to find your next great read among them.

The Millions will be taking a hiatus for the next few months, but we hope to see you soon.

—Sophia Stewart, editor

January

The Legend of Kumai by Shirato Sanpei, tr. Richard Rubinger (Drawn & Quarterly)

The epic 10-volume series, a touchstone of longform storytelling in manga now published in English for the first time, follows outsider Kamui in 17th-century Japan as he fights his way up from peasantry to the prized role of ninja. —Michael J. Seidlinger

The Life of Herod the Great by Zora Neale Hurston (Amistad)

In the years before her death in 1960, Hurston was at work on what she envisioned as a continuation of her 1939 novel, Moses, Man of the Mountain. Incomplete, nearly lost to fire, and now published for the first time alongside scholarship from editor Deborah G. Plant, Hurston’s final manuscript reimagines Herod, villain of the New Testament Gospel accounts, as a magnanimous and beloved leader of First Century Judea. —Jonathan Frey

Mood Machine by Liz Pelly (Atria)

When you eagerly posted your Spotify Wrapped last year, did you notice how much of what you listened to tended to sound... the same? Have you seen all those links to Bandcamp pages your musician friends keep desperately posting in the hopes that maybe, just maybe, you might give them money for their art? If so, this book is for you. —John H. Maher

My Country, Africa by Andrée Blouin (Verso)

African revolutionary Blouin recounts a radical life steeped in activism in this vital autobiography, from her beginnings in a colonial orphanage to her essential role in the continent's midcentury struggles for decolonization. —Sophia M. Stewart

The First and Last King of Haiti by Marlene L. Daut (Knopf)

Donald Trump repeatedly directs extraordinary animus towards Haiti and Haitians. This biography of Henry Christophe—the man who played a pivotal role in the Haitian Revolution—might help Americans understand why. —Claire Kirch

The Bewitched Bourgeois by Dino Buzzati, tr. Lawrence Venuti (NYRB)

This is the second story collection, and fifth book, by the absurdist-leaning midcentury Italian writer—whose primary preoccupation was war novels that blend the brutal with the fantastical—to get the NYRB treatment. May it not be the last. —JHM

Y2K by Colette Shade (Dey Street)

The recent Y2K revival mostly makes me feel old, but Shade's essay collection deftly illuminates how we got here, connecting the era's social and political upheavals to today. —SMS

Darkmotherland by Samrat Upadhyay (Penguin)

In a vast dystopian reimagining of Nepal, Upadhyay braids narratives of resistance (political, personal) and identity (individual, societal) against a backdrop of natural disaster and state violence. The first book in nearly a decade from the Whiting Award–winning author of Arresting God in Kathmandu, this is Upadhyay’s most ambitious yet. —JF

Metamorphosis by Ross Jeffery (Truborn)

From the author of I Died Too, But They Haven’t Buried Me Yet, a woman leads a double life as she loses her grip on reality by choice, wearing a mask that reflects her inner demons, as she descends into a hell designed to reveal the innermost depths of her grief-stricken psyche. —MJS

The Containment by Michelle Adams (FSG)

Legal scholar Adams charts the failure of desegregation in the American North through the story of the struggle to integrate suburban schools in Detroit, which remained almost completely segregated nearly two decades after Brown v. Board. —SMS

Death of the Author by Nnedi Okorafor (Morrow)

African Futurist Okorafor’s book-within-a-book offers interchangeable cover images, one for the story of a disabled, Black visionary in a near-present day and the other for the lead character’s speculative posthuman novel, Rusted Robots. Okorafor deftly keeps the alternating chapters and timelines in conversation with one another. —Nathalie op de Beeck

Open Socrates by Agnes Callard (Norton)

Practically everything Agnes Callard says or writes ushers in a capital-D Discourse. (Remember that profile?) If she can do the same with a study of the philosophical world’s original gadfly, culture will be better off for it. —JHM

Aflame by Pico Iyer (Riverhead)

Presumably he finds time to eat and sleep in there somewhere, but it certainly appears as if Iyer does nothing but travel and write. His latest, following 2023’s The Half Known Life, makes a case for the sublimity, and necessity, of silent reflection. —JHM

The In-Between Bookstore by Edward Underhill (Avon)

A local bookstore becomes a literal portal to the past for a trans man who returns to his hometown in search of a fresh start in Underhill's tender debut. —SMS

Good Girl by Aria Aber (Hogarth)

Aber, an accomplished poet, turns to prose with a debut novel set in the electric excess of Berlin’s bohemian nightlife scene, where a young German-born Afghan woman finds herself enthralled by an expat American novelist as her country—and, soon, her community—is enflamed by xenophobia. —JHM

The Orange Eats Creeps by Grace Krilanovich (Two Dollar Radio)

Krilanovich’s 2010 cult classic, about a runaway teen with drug-fueled ESP who searches for her missing sister across surreal highways while being chased by a killer named Dactyl, gets a much-deserved reissue. —MJS

Mona Acts Out by Mischa Berlinski (Liveright)

In the latest novel from the National Book Award finalist, a 50-something actress reevaluates her life and career when #MeToo allegations roil the off-off-Broadway Shakespearean company that has cast her in the role of Cleopatra. —SMS

Something Rotten by Andrew Lipstein (FSG)

A burnt-out couple leave New York City for what they hope will be a blissful summer in Denmark when their vacation derails after a close friend is diagnosed with a rare illness and their marriage is tested by toxic influences. —MJS

The Sun Won't Come Out Tomorrow by Kristen Martin (Bold Type)

Martin's debut is a cultural history of orphanhood in America, from the 1800s to today, interweaving personal narrative and archival research to upend the traditional "orphan narrative," from Oliver Twist to Annie. —SMS

We Do Not Part by Han Kang, tr. E. Yaewon and Paige Aniyah Morris (Hogarth)

Kang’s Nobel win last year surprised many, but the consistency of her talent certainly shouldn't now. The latest from the author of The Vegetarian—the haunting tale of a Korean woman who sets off to save her injured friend’s pet at her home in Jeju Island during a deadly snowstorm—will likely once again confront the horrors of history with clear eyes and clarion prose. —JHM

We Are Dreams in the Eternal Machine by Deni Ellis Béchard (Milkweed)

As the conversation around emerging technology skews increasingly to apocalyptic and utopian extremes, Béchard’s latest novel adopts the heterodox-to-everyone approach of embracing complexity. Here, a cadre of characters is isolated by a rogue but benevolent AI into controlled environments engineered to achieve their individual flourishing. The AI may have taken over, but it only wants to best for us. —JF

The Harder I Fight the More I Love You by Neko Case (Grand Central)

Singer-songwriter Case, a country- and folk-inflected indie rocker and sometime vocalist for the New Pornographers, takes her memoir’s title from her 2013 solo album. Followers of PNW music scene chronicles like Kathleen Hanna’s Rebel Girl and drummer Steve Moriarty’s Mia Zapata and the Gits will consider Case’s backstory a must-read. —NodB

The Loves of My Life by Edmund White (Bloomsbury)

The 85-year-old White recounts six decades of love and sex in this candid and erotic memoir, crafting a landmark work of queer history in the process. Seminal indeed. —SMS

Blob by Maggie Su (Harper)

In Su’s hilarious debut, Vi Liu is a college dropout working a job she hates, nothing really working out in her life, when she stumbles across a sentient blob that she begins to transform as her ideal, perfect man that just might resemble actor Ryan Gosling. —MJS

Sinkhole and Other Inexplicable Voids by Leyna Krow (Penguin)

Krow’s debut novel, Fire Season, traced the combustible destinies of three Northwest tricksters in the aftermath of an 1889 wildfire. In her second collection of short fiction, Krow amplifies surreal elements as she tells stories of ordinary lives. Her characters grapple with deadly viruses, climate change, and disasters of the Anthropocene’s wilderness. —NodB

Black in Blues by Imani Perry (Ecco)

The National Book Award winner—and one of today's most important thinkers—returns with a masterful meditation on the color blue and its role in Black history and culture. —SMS

Too Soon by Betty Shamieh (Avid)

The timely debut novel by Shamieh, a playwright, follows three generations of Palestinian American women as they navigate war, migration, motherhood, and creative ambition. —SMS

How to Talk About Love by Plato, tr. Armand D'Angour (Princeton UP)

With modern romance on its last legs, D'Angour revisits Plato's Symposium, mining the philosopher's masterwork for timeless, indispensable insights into love, sex, and attraction. —SMS

At Dark, I Become Loathsome by Eric LaRocca (Blackstone)

After Ashley Lutin’s wife dies, he takes the grieving process in a peculiar way, posting online, “If you're reading this, you've likely thought that the world would be a better place without you,” and proceeds to offer a strange ritual for those that respond to the line, equally grieving and lost, in need of transcendence. —MJS

February

No One Knows by Osamu Dazai, tr. Ralph McCarthy (New Directions)

A selection of stories translated in English for the first time, from across Dazai’s career, demonstrates his penchant for exploring conformity and society’s often impossible expectations of its members. —MJS

Mutual Interest by Olivia Wolfgang-Smith (Bloomsbury)

This queer love story set in post–Gilded Age New York, from the author of Glassworks (and one of my favorite Millions essays to date), explores on sex, power, and capitalism through the lives of three queer misfits. —SMS

Pure, Innocent Fun by Ira Madison III (Random House)

This podcaster and pop culture critic spoke to indie booksellers at a fall trade show I attended, regaling us with key cultural moments in the 1990s that shaped his youth in Milwaukee and being Black and gay. If the book is as clever and witty as Madison is, it's going to be a winner. —CK

Gliff by Ali Smith (Pantheon)

The Scottish author has been on the scene since 1997 but is best known today for a seasonal quartet from the late twenty-teens that began in 2016 with Autumn and ended in 2020 with Summer. Here, she takes the genre turn, setting two children and a horse loose in an authoritarian near future. —JHM

Land of Mirrors by Maria Medem, tr. Aleshia Jensen and Daniela Ortiz (D&Q)

This hypnotic graphic novel from one of Spain's most celebrated illustrators follows Antonia, the sole inhabitant of a deserted town, on a color-drenched quest to preserve the dying flower that gives her purpose. —SMS

Bibliophobia by Sarah Chihaya (Random House)

As odes to the "lifesaving power of books" proliferate amid growing literary censorship, Chihaya—a brilliant critic and writer—complicates this platitude in her revelatory memoir about living through books and the power of reading to, in the words of blurber Namwali Serpell, "wreck and redeem our lives." —SMS

Reading the Waves by Lidia Yuknavitch (Riverhead)

Yuknavitch continues the personal story she began in her 2011 memoir, The Chronology of Water. More than a decade after that book, and nearly undone by a history of trauma and the death of her daughter, Yuknavitch revisits the solace she finds in swimming (she was once an Olympic hopeful) and in her literary community. —NodB

The Dissenters by Youssef Rakha (Graywolf)

A son reevaluates the life of his Egyptian mother after her death in Rakha's novel. Recounting her sprawling life story—from her youth in 1960s Cairo to her experience of the 2011 Tahrir Square protests—a vivid portrait of faith, feminism, and contemporary Egypt emerges. —SMS

Tetra Nova by Sophia Terazawa (Deep Vellum)

Deep Vellum has a particularly keen eye for fiction in translation that borders on the unclassifiable. This debut from a poet the press has published twice, billed as the story of “an obscure Roman goddess who re-imagines herself as an assassin coming to terms with an emerging performance artist identity in the late-20th century,” seems right up that alley. —JHM

David Lynch's American Dreamscape by Mike Miley (Bloomsbury)

Miley puts David Lynch's films in conversation with literature and music, forging thrilling and unexpected connections—between Eraserhead and "The Yellow Wallpaper," Inland Empire and "mixtape aesthetics," Lynch and the work of Cormac McCarthy. Lynch devotees should run, not walk. —SMS

There's No Turning Back by Alba de Céspedes, tr. Ann Goldstein (Washington Square)

Goldstein is an indomitable translator. Without her, how would you read Ferrante? Here, she takes her pen to a work by the great Cuban-Italian writer de Céspedes, banned in the fascist Italy of the 1930s, that follows a group of female literature students living together in a Roman boarding house. —JHM

Beta Vulgaris by Margie Sarsfield (Norton)

Named for the humble beet plant and meaning, in a rough translation from the Latin, "vulgar second," Sarsfield’s surreal debut finds a seasonal harvest worker watching her boyfriend and other colleagues vanish amid “the menacing but enticing siren song of the beets.” —JHM

People From Oetimu by Felix Nesi, tr. Lara Norgaard (Archipelago)

The center of Nesi’s wide-ranging debut novel is a police station on the border between East and West Timor, where a group of men have gathered to watch the final of the 1998 World Cup while a political insurgency stirs without. Nesi, in English translation here for the first time, circles this moment broadly, reaching back to the various colonialist projects that have shaped Timor and the lives of his characters. —JF

Brother Brontë by Fernando A. Flores (MCD)

This surreal tale, set in a 2038 dystopian Texas is a celebration of resistance to authoritarianism, a mash-up of Olivia Butler, Ray Bradbury, and John Steinbeck. —CK

Alligator Tears by Edgar Gomez (Crown)

The High-Risk Homosexual author returns with a comic memoir-in-essays about fighting for survival in the Sunshine State, exploring his struggle with poverty through the lens of his queer, Latinx identity. —SMS

Theory & Practice by Michelle De Kretser (Catapult)

This lightly autofictional novel—De Krester's best yet, and one of my favorite books of this year—centers on a grad student's intellectual awakening, messy romantic entanglements, and fraught relationship with her mother as she minds the gap between studying feminist theory and living a feminist life. —SMS

The Lamb by Lucy Rose (Harper)

Rose’s cautionary and caustic folk tale is about a mother and daughter who live alone in the forest, quiet and tranquil except for the visitors the mother brings home, whom she calls “strays,” wining and dining them until they feast upon the bodies. —MJS

Disposable by Sarah Jones (Avid)

Jones, a senior writer for New York magazine, gives a voice to America's most vulnerable citizens, who were deeply and disproportionately harmed by the pandemic—a catastrophe that exposed the nation's disregard, if not outright contempt, for its underclass. —SMS

No Fault by Haley Mlotek (Viking)

Written in the aftermath of the author's divorce from the man she had been with for 12 years, this "Memoir of Romance and Divorce," per its subtitle, is a wise and distinctly modern accounting of the end of a marriage, and what it means on a personal, social, and literary level. —SMS

Enemy Feminisms by Sophie Lewis (Haymarket)

Lewis, one of the most interesting and provocative scholars working today, looks at certain malignant strains of feminism that have done more harm than good in her latest book. In the process, she probes the complexities of gender equality and offers an alternative vision of a feminist future. —SMS

Lion by Sonya Walger (NYRB)

Walger—an successful actor perhaps best known for her turn as Penny Widmore on Lost—debuts with a remarkably deft autobiographical novel (published by NYRB no less!) about her relationship with her complicated, charismatic Argentinian father. —SMS

The Voices of Adriana by Elvira Navarro, tr. Christina MacSweeney (Two Lines)

A Spanish writer and philosophy scholar grieves her mother and cares for her sick father in Navarro's innovative, metafictional novel. —SMS

Autotheories ed. Alex Brostoff and Vilashini Cooppan (MIT)

Theory wonks will love this rigorous and surprisingly playful survey of the genre of autotheory—which straddles autobiography and critical theory—with contributions from Judith Butler, Jamieson Webster, and more.

Fagin the Thief by Allison Epstein (Doubleday)

I enjoy retellings of classic novels by writers who turn the spotlight on interesting minor characters. This is an excursion into the world of Charles Dickens, told from the perspective iconic thief from Oliver Twist. —CK

Crush by Ada Calhoun (Viking)

Calhoun—the masterful memoirist behind the excellent Also A Poet—makes her first foray into fiction with a debut novel about marriage, sex, heartbreak, all-consuming desire. —SMS

Show Don't Tell by Curtis Sittenfeld (Random House)

Sittenfeld's observations in her writing are always clever, and this second collection of short fiction includes a tale about the main character in Prep, who visits her boarding school decades later for an alumni reunion. —CK

Right-Wing Woman by Andrea Dworkin (Picador)

One in a trio of Dworkin titles being reissued by Picador, this 1983 meditation on women and American conservatism strikes a troublingly resonant chord in the shadow of the recent election, which saw 45% of women vote for Trump. —SMS

The Talent by Daniel D'Addario (Scout)

If your favorite season is awards, the debut novel from D'Addario, chief correspondent at Variety, weaves an awards-season yarn centering on five stars competing for the Best Actress statue at the Oscars. If you know who Paloma Diamond is, you'll love this. —SMS

Death Takes Me by Cristina Rivera Garza, tr. Sarah Booker and Robin Myers (Hogarth)

The Pulitzer winner’s latest is about an eponymously named professor who discovers the body of a mutilated man with a bizarre poem left with the body, becoming entwined in the subsequent investigation as more bodies are found. —MJS

The Strange Case of Jane O. by Karen Thompson Walker (Random House)

Jane goes missing after a sudden a debilitating and dreadful wave of symptoms that include hallucinations, amnesia, and premonitions, calling into question the foundations of her life and reality, motherhood and buried trauma. —MJS

Song So Wild and Blue by Paul Lisicky (HarperOne)

If it weren’t Joni Mitchell’s world with all of us just living in it, one might be tempted to say the octagenarian master songstress is having a moment: this memoir of falling for the blue beauty of Mitchell’s work follows two other inventive books about her life and legacy: Ann Powers's Traveling and Henry Alford's I Dream of Joni. —JHM

Mornings Without Mii by Mayumi Inaba, tr. Ginny Tapley (FSG)

A woman writer meditates on solitude, art, and independence alongside her beloved cat in Inaba's modern classic—a book so squarely up my alley I'm somehow embarrassed. —SMS

True Failure by Alex Higley (Coffee House)

When Ben loses his job, he decides to pretend to go to work while instead auditioning for Big Shot, a popular reality TV show that he believes might be a launchpad for his future successes. —MJS

March

Woodworking by Emily St. James (Crooked Reads)

Those of us who have been reading St. James since the A.V. Club days may be surprised to see this marvelous critic's first novel—in this case, about a trans high school teacher befriending one of her students, the only fellow trans woman she’s ever met—but all the more excited for it. —JHM

Optional Practical Training by Shubha Sunder (Graywolf)

Told as a series of conversations, Sunder’s debut novel follows its recently graduated Indian protagonist in 2006 Cambridge, Mass., as she sees out her student visa teaching in a private high school and contriving to find her way between worlds that cannot seem to comprehend her. Quietly subversive, this is an immigration narrative to undermine the various reductionist immigration narratives of our moment. —JF

Love, Queenie by Mayukh Sen (Norton)

Merle Oberon, one of Hollywood's first South Asian movie stars, gets her due in this engrossing biography, which masterfully explores Oberon's painful upbringing, complicated racial identity, and much more. —SMS

The Age of Choice by Sophia Rosenfeld (Princeton UP)

At a time when we are awash with options—indeed, drowning in them—Rosenfeld's analysis of how our modingn idea of "freedom" became bound up in the idea of personal choice feels especially timely, touching on everything from politics to romance. —SMS

Sucker Punch by Scaachi Koul (St. Martin's)

One of the internet's funniest writers follows up One Day We'll All Be Dead and None of This Will Matter with a sharp and candid collection of essays that sees her life go into a tailspin during the pandemic, forcing her to reevaluate her beliefs about love, marriage, and what's really worth fighting for. —SMS

The Mysterious Disappearance of the Marquise of Loria by José Donoso, tr. Megan McDowell (New Directions)

The ever-excellent McDowell translates yet another work by the influential Chilean author for New Directions, proving once again that Donoso had a knack for titles: this one follows up 2024’s behemoth The Obscene Bird of Night. —JHM

Remember This by Anthony Giardina (FSG)

On its face, it’s another book about a writer living in Brooklyn. A layer deeper, it’s a book about fathers and daughters, occupations and vocations, ethos and pathos, failure and success. —JHM

Ultramarine by Mariette Navarro (Deep Vellum)

In this metaphysical and lyrical tale, a captain known for sticking to protocol begins losing control not only of her crew and ship but also her own mind. —MJS

We Tell Ourselves Stories by Alissa Wilkinson (Liveright)

Amid a spate of new books about Joan Didion published since her death in 2021, this entry by Wilkinson (one of my favorite critics working today) stands out for its approach, which centers Hollywood—and its meaning-making apparatus—as an essential key to understanding Didion's life and work. —SMS

Seven Social Movements that Changed America by Linda Gordon (Norton)

This book—by a truly renowned historian—about the power that ordinary citizens can wield when they organize to make their community a better place for all could not come at a better time. —CK

Mothers and Other Fictional Characters by Nicole Graev Lipson (Chronicle Prism)

Lipson reconsiders the narratives of womanhood that constrain our lives and imaginations, mining the canon for alternative visions of desire, motherhood, and more—from Kate Chopin and Gwendolyn Brooks to Philip Roth and Shakespeare—to forge a new story for her life. —SMS

Goddess Complex by Sanjena Sathian (Penguin)

Doppelgängers have been done to death, but Sathian's examination of Millennial womanhood—part biting satire, part twisty thriller—breathes new life into the trope while probing the modern realities of procreation, pregnancy, and parenting. —SMS

Stag Dance by Torrey Peters (Random House)

The author of Detransition, Baby offers four tales for the price of one: a novel and three stories that promise to put gender in the crosshairs with as sharp a style and swagger as Peters’ beloved latest. The novel even has crossdressing lumberjacks. —JHM

On Breathing by Jamieson Webster (Catapult)

Webster, a practicing psychoanalyst and a brilliant writer to boot, explores that most basic human function—breathing—to address questions of care and interdependence in an age of catastrophe. —SMS

Unusual Fragments: Japanese Stories (Two Lines)

The stories of Unusual Fragments, including work by Yoshida Tomoko, Nobuko Takai, and other seldom translated writers from the same ranks as Abe and Dazai, comb through themes like alienation and loneliness, from a storm chaser entering the eye of a storm to a medical student observing a body as it is contorted into increasingly violent positions. —MJS

The Antidote by Karen Russell (Knopf)

Russell has quipped that this Dust Bowl story of uncanny happenings in Nebraska is the “drylandia” to her 2011 Florida novel, Swamplandia! In this suspenseful account, a woman working as a so-called prairie witch serves as a storage vault for her townspeople’s most troubled memories of migration and Indigenous genocide. With a murderer on the loose, a corrupt sheriff handling the investigation, and a Black New Deal photographer passing through to document Americana, the witch loses her memory and supernatural events parallel the area’s lethal dust storms. —NodB

On the Clock by Claire Baglin, tr. Jordan Stump (New Directions)

Baglin's bildungsroman, translated from the French, probes the indignities of poverty and service work from the vantage point of its 20-year-old narrator, who works at a fast-food joint and recalls memories of her working-class upbringing. —SMS

Motherdom by Alex Bollen (Verso)

Parenting is difficult enough without dealing with myths of what it means to be a good mother. I who often felt like a failure as a mother appreciate Bollen's focus on a more realistic approach to parenting. —CK

The Magic Books by Anne Lawrence-Mathers (Yale UP)

For that friend who wants to concoct the alchemical elixir of life, or the person who cannot quit Susanna Clark’s Jonathan Strange and Mr. Norrell, Lawrence-Mathers collects 20 illuminated medieval manuscripts devoted to magical enterprise. Her compendium includes European volumes on astronomy, magical training, and the imagined intersection between science and the supernatural. —NodB

Theft by Abdulrazak Gurnah (Riverhead)

The first novel by the Tanzanian-British Nobel laureate since his surprise win in 2021 is a story of class, seismic cultural change, and three young people in a small Tanzania town, caught up in both as their lives dramatically intertwine. —JHM

Twelve Stories by American Women, ed. Arielle Zibrak (Penguin Classics)

Zibrak, author of a delicious volume on guilty pleasures (and a great essay here at The Millions), curates a dozen short stories by women writers who have long been left out of American literary canon—most of them women of color—from Frances Ellen Watkins Harper to Zitkala-Ša. —SMS

I'll Love You Forever by Giaae Kwon (Holt)

K-pop’s sky-high place in the fandom landscape made a serious critical assessment inevitable. This one blends cultural criticism with memoir, using major artists and their careers as a lens through which to view the contemporary Korean sociocultural landscape writ large. —JHM

The Buffalo Hunter Hunter by Stephen Graham Jones (Saga)

Jones, the acclaimed author of The Only Good Indians and the Indian Lake Trilogy, offers a unique tale of historical horror, a revenge tale about a vampire descending upon the Blackfeet reservation and the manifold of carnage in their midst. —MJS

True Mistakes by Lena Moses-Schmitt (University of Arkansas Press)

Full disclosure: Lena is my friend. But part of why I wanted to be her friend in the first place is because she is a brilliant poet. Selected by Patricia Smith as a finalist for the Miller Williams Poetry Prize, and blurbed by the great Heather Christle and Elisa Gabbert, this debut collection seeks to turn "mistakes" into sites of possibility. —SMS

Perfection by Vicenzo Latronico, tr. Sophie Hughes (NYRB)

Anna and Tom are expats living in Berlin enjoying their freedom as digital nomads, cultivating their passion for capturing perfect images, but after both friends and time itself moves on, their own pocket of creative freedom turns boredom, their life trajectories cast in doubt. —MJS

Guatemalan Rhapsody by Jared Lemus (Ecco)

Jemus's debut story collection paint a composite portrait of the people who call Guatemala home—and those who have left it behind—with a cast of characters that includes a medicine man, a custodian at an underfunded college, wannabe tattoo artists, four orphaned brothers, and many more.

Pacific Circuit by Alexis Madrigal (MCD)

The Oakland, Calif.–based contributing writer for the Atlantic digs deep into the recent history of a city long under-appreciated and under-served that has undergone head-turning changes throughout the rise of Silicon Valley. —JHM

Barbara by Joni Murphy (Astra)

Described as "Oppenheimer by way of Lucia Berlin," Murphy's character study follows the titular starlet as she navigates the twinned convulsions of Hollywood and history in the Atomic Age.

Sister Sinner by Claire Hoffman (FSG)

This biography of the fascinating Aimee Semple McPherson, America's most famous evangelist, takes religion, fame, and power as its subjects alongside McPherson, whose life was suffused with mystery and scandal. —SMS

Trauma Plot by Jamie Hood (Pantheon)

In this bold and layered memoir, Hood confronts three decades of sexual violence and searches for truth among the wreckage. Kate Zambreno calls Trauma Plot the work of "an American Annie Ernaux." —SMS

Hey You Assholes by Kyle Seibel (Clash)

Seibel’s debut story collection ranges widely from the down-and-out to the downright bizarre as he examines with heart and empathy the strife and struggle of his characters. —MJS

James Baldwin by Magdalena J. Zaborowska (Yale UP)

Zaborowska examines Baldwin's unpublished papers and his material legacy (e.g. his home in France) to probe about the great writer's life and work, as well as the emergence of the "Black queer humanism" that Baldwin espoused. —CK

Stop Me If You've Heard This One by Kristen Arnett (Riverhead)

Arnett is always brilliant and this novel about the relationship between Cherry, a professional clown, and her magician mentor, "Margot the Magnificent," provides a fascinating glimpse of the unconventional lives of performance artists. —CK

Paradise Logic by Sophie Kemp (S&S)

The deal announcement describes the ever-punchy writer’s debut novel with an infinitely appealing appellation: “debauched picaresque.” If that’s not enough to draw you in, the truly unhinged cover should be. —JHM

[millions_email]

A Year in Reading: 2024

Welcome to the 20th (!) installment of The Millions' annual Year in Reading series, which gathers together some of today's most exciting writers and thinkers to share the books that shaped their year. YIR is not a collection of yearend best-of lists; think of it, perhaps, as an assemblage of annotated bibliographies. We've invited contributors to reflect on the books they read this year—an intentionally vague prompt—and encouraged them to approach the assignment however they choose.

In writing about our reading lives, as YIR contributors are asked to do, we inevitably write about our personal lives, our inner lives. This year, a number of contributors read their way through profound grief and serious illness, through new parenthood and cross-country moves. Some found escape in frothy romances, mooring in works of theology, comfort in ancient epic poetry. More than one turned to the wisdom of Ursula K. Le Guin. Many describe a book finding them just when they needed it.

Interpretations of the assignment were wonderfully varied. One contributor, a music critic, considered the musical analogs to the books she read, while another mapped her reads from this year onto constellations. Most people's reading was guided purely by pleasure, or else a desire to better understand events unfolding in their lives or larger the world. Yet others centered their reading around a certain sense of duty: this year one contributor committed to finishing the six Philip Roth novels he had yet to read, an undertaking that he likens to “eating a six-pack of paper towels.” (Lucky for us, he included in his essay his final ranking of Roth's oeuvre.)

The books that populate these essays range widely, though the most commonly noted title this year was Tony Tulathimutte’s story collection Rejection. The work of newly minted National Book Award winner Percival Everett, particularly his acclaimed novel James, was also widely read and written about. And as the genocide of Palestinians in Gaza enters its second year, many contributors sought out Isabella Hammad’s searing, clear-eyed essay Recognizing the Stranger.

Like so many endeavors in our chronically under-resourced literary community, Year in Reading is a labor of love. The Millions is a one-person editorial operation (with an invaluable assist from SEO maven Dani Fishman), and producing YIR—and witnessing the joy it brings contributors and readers alike—has been the highlight of my tenure as editor. I’m profoundly grateful for the generosity of this year’s contributors, whose names and entries will be revealed below over the next three weeks, concluding on Wednesday, December 18. Be sure to subscribe to The Millions’ free newsletter to get the week’s entries sent straight to your inbox each Friday.

—Sophia Stewart, editor

Becca Rothfeld, author of All Things Are Too Small

Carvell Wallace, author of Another Word for Love

Charlotte Shane, author of An Honest Woman

Brianna Di Monda, writer and editor

Nell Irvin Painter, author of I Just Keep Talking

Carrie Courogen, author of Miss May Does Not Exist

Ayşegül Savaş, author of The Anthropologists

Zachary Issenberg, writer

Tony Tulathimutte, author of Rejection

Ann Powers, author of Traveling: On the Path of Joni Mitchell

Lidia Yuknavitch, author of Reading the Waves

Nicholas Russell, writer and critic

Daniel Saldaña París, author of Planes Flying Over a Monster

Lili Anolik, author of Didion and Babitz

Deborah Ghim, editor

Emily Witt, author of Health and Safety

Nathan Thrall, author of A Day in the Life of Abed Salama

Lena Moses-Schmitt, author of True Mistakes

Jeremy Gordon, author of See Friendship

John Lee Clark, author of Touch the Future

Ellen Wayland-Smith, author of The Science of Last Things

Edwin Frank, publisher and author of Stranger Than Fiction

Sophia Stewart, editor of The Millions

A Year in Reading Archives: 2023, 2022, 2021, 2020, 2019, 2018, 2017, 2016, 2015, 2014, 2013, 2011, 2010, 2009, 2008, 2007, 2006, 2005

A Year in Reading: Lisa Halliday

It has been a year of reading in fits and starts, indeed of doing everything in fits and starts, fits and starts being the general run of things when you have a baby.

For articles I was writing, I happily revisited passages from several books, including:

Little Women

Elizabeth Costello

The Garden of Eden

Tropic of Capricorn

Bartleby & Co.

A Sport and a Pastime

Yann Andréa Steiner

NW

To the Back of Beyond

Charlotte’s Web

For my next novel, I read bits of books about fathers, including letters between Wolfgang and Leopold Mozart; books about Italians, including Luce D’Eramo’s Deviation; and books about conspiracy theories and “the power of the lie,” including David Aaronovitch’s Voodoo Histories, Rob Brotherton’s Suspicious Minds, Hans Rosling’s Factfulness, and a timely new anthology entitled Orwell on Truth.

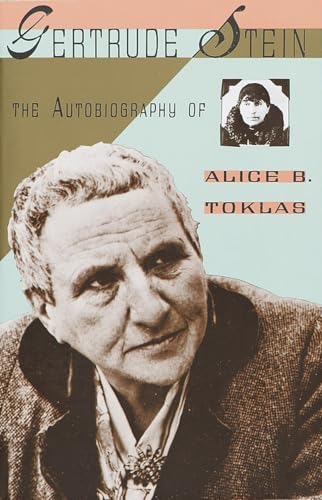

I read books that were sent to me, including Free Woman by Lara Feigel and the forthcoming Such Good Work by Johannes Lichtman. In preparation for events, I read Kevin Powers’s A Shout in the Ruins, Aminatta Forna’s Happiness, Gertrude Stein’s The Autobiography of Alice B. Toklas, Aja Gabel’s The Ensemble, and Kim Fu’s The Lost Girls of Camp Forevermore. Each made me grateful for the forces that delivered it over my transom.

In London I read Sally Rooney’s absorbing Conversations with Friends while my daughter patiently paged through an old copy of The Cricket Caricatures of John Ireland.

In Tobermory I read about the history of lighthouses and Robert Louis Stevenson’s Kidnapped in The Cicerone Guide to Walking on The Isle of Mull.

On a flight from San Francisco to Boston I read Nick Drnaso’s Sabrina and wished it were twice as long.

On Thanksgiving I read Updike: Novels 1959-1965, including the biographical chronology at the end, marveling at a prolificacy I think only Simenon outmatched.

I read The New York Times, most avidly the obituaries, which are like little novels.

I read The New Yorker. I also listened to The New Yorker, and to Jeremy Black’s A Brief History of Italy, and Hermione Hoby’s Neon in Daylight, because of course listening is a way of reading when your hands and eyes are otherwise occupied.

I read books about motherhood, including the Sebaldian Sight, by Jessie Greengrass; And Now We Have Everything, by Meaghan O’Connell; and too many books about how to get your baby to sleep, none of which helped except for the one that asked me to consider what kind of memories of my daughter’s infancy I would like to have.

I re-read Strunk & White.

I read What’s Going on in There?: How the Brain and Mind Develop in the First Five Years of Life, which Philip Roth sent me 40 days before he died.

And, with my daughter in my lap, I read many more books, most of them multiple times, including Il flauto magico, One White Rabbit, The Range Eternal, Where’s Mr. Lion?, Giochiamo a nascondino!, Pinocchio, Biancaneve, Good Night, Red Sox, and an especially treasured box set illustrated by the late artist Leo Lionni: Due topolini curiosi, whose cover features a duly curious little mouse with her whiskers buried in a book.

More from A Year in Reading 2018

Do you love Year in Reading and the amazing books and arts content that The Millions produces year round? We are asking readers for support to ensure that The Millions can stay vibrant for years to come. Please click here to learn about several simple ways you can support The Millions now.

Don’t miss: A Year in Reading 2017, 2016, 2015, 2014, 2013, 2012, 2011, 2010, 2009, 2008, 2007, 2006, 2005

[millions_ad]

Hell with the Lid Taken Off: A Pittsburgh Reading List

The most unexpected literary metropolis in the United States is Pittsburgh. Known less for literature than for producing more steel than any other place on Earth, Pittsburgh was literally the Ally’s arsenal during WWII and was central in America’s 20th-century ascent. But when industry collapsed during the Reagan administration, it -- like her sisters Cleveland, Cincinnati, Buffalo, and Detroit -- became a region adrift. For years the city was a Rust Belt punch line to those too ill-informed to experience the tough beauty of the place. And yet economics can be destiny, which is why it’s heartening, surprising, and in some sense worrying to see Pittsburgh discovered now by national magazines and newspapers which are always looking for the next location, a new Portland or Austin where arty people with expendable cash can drink craft beer and go to pop-up art galleries. In a few years we’ve gone from being the “Paris of Appalachia” (as if there should be any shame in that!) to Williamsburg on the Three Rivers. Yet the place itself remains more complicated, confusing, contradictory, beautiful, and glorious than the national media ever realized.

These dichotomies are too simple, though; they skirt the reality of a place, especially one that was so central in the “consequence of America” (as Pittsburgh poet Jack Gilbert put it). Pittsburgh is a synecdoche for the nation, a microcosm of the things that made America magnificent, but also of the things that damaged the country. There is great drama in its story, from being the first metropolis on that ever westward expanding frontier, to becoming the industrial “hell with the lid taken off” of Victorian essayist James Parton, to the reinventions of today. This is inevitably the stuff of great literature.

No less than Herman Melville once declared that “men not very much inferior to Shakespeare are this day being born on the banks of the Ohio.” Gilbert echoed Melville, when he remarked to The Paris Review, “You can’t think small in a steel mill.” Part of this is because the area certainly has a lot that can be written about: dramatic topography and sometimes-tragic history, cosmopolitan expansiveness as well as damaging provincialism, the still almost inexplicable physical beauty and the grime of industry. No declaration of it as the “Most Livable City in America” can fully contain these paradoxes. But in the writing of Willa Cather, John Edgar Wideman, Michael Chabon, Stewart O’Nan, and Ellen Litman we see a fuller expression of the raw energy of Pittsburgh than one does in the simple platitudes of official civic boosters.

As a native Pittsburgher, even when I was young, I intuited how heavy and determined the history of the city was, the very surroundings a sort of palimpsest. As with that type of manuscript, even though there may be an accumulation of layers of new letters on top, the previous generations’ words can still be visible underneath, if not always legible. What follows is a recommended reading list that tries to elucidate the nature of this palimpsest. We shouldn’t be surprised by that variety of voices. Pittsburgh continues to have a thriving literary scene outside of all proportion for its size, not just in the celebrated creative writing departments at the University of Pittsburgh, Carnegie Mellon, and other colleges and universities in the area, but in initiatives like City of Asylum, which houses writers in exile from their home nations; the writers’ network Litsburgh; or the small bookstore scene (with the welcome recent return of the excellent City Books). The region lends itself to such sublime inspirations as to create poets and writers of a surprising caliber, as Annie Dillard herself imagines Pittsburgh “poured rolling down the mountain valleys like slag” where she can “see the city lights sprinkled and curved around the hills’ curves, rows of bonfires winding. At sunset a red light like house fires shines from the narrow hillside windows; the houses’ bricks burn like glowing coals.” Gilbert was right; it’s hard to think small here.

1. Modern Chivalry: Containing the Adventures of Captain John Farrago and Teague O'Regan, His Servant by Hugh Henry Brackenridge (1792)

One candidate for the first actual American novel is the first work on this list. Although rarely read by anyone other than specialists today, Brackenridge conceived of Modern Chivalry as an American Don Quixote, a maximalist attempt to convey the full complexity, vigor, and reality of life on the western frontier. The errant knight in Breckenridge’s massive novel is John Farrago, who decides to “ride about the world a little…to see how things were going on here and there, and to observe human nature.” In his endeavors through the western Pennsylvanian landscape, Farrago’s Sancho Panza is a drunken Irish layabout named Teague O’Regan. Along the way, Brackenridge presents his readers with a Pynchonesque satire of an America on the verge of both the second great awakening and ultimately Jacksonian democracy, making the first American novel also the first road novel. Brackenridge was in some ways as quixotic as the character he created. Scottish by birth and Philadelphian by upbringing, Breckenridge’s literary ambitions began at Princeton, where he wrote the poem "The Rising Glory of America" (about what you’d expect) with his friend Philip Freneau and delivered it on the steps of Nassau Hall in 1771 in a pique of revolutionary fervor. After the War of Independence, he set out to the west to make his fortunes in Pittsburgh, which though already the metropolis of Trans-Appalachia was still a frontier settlement of no more than 400 people. While there Brackenridge would make himself the “great man” that he felt he had the potential to be, a potential that due to its large size would not be realized in that Quaker city to the east. Brackenridge afforded himself of every opportunity the growing western settlement offered, not just writing Modern Chivalry but both founding what would be The Pittsburgh Post-Gazette and the University of Pittsburgh. In Modern Chivalry he proves Ralph Waldo Emerson’s assertion that “Europe extends to the Alleghenies; America lies beyond,” depicting a growing city that was part of France longer than it was in Britain, and thus becomes more originally American than Puritan Boston, Quaker Philadelphia, Dutch New York, or Cavalier Baltimore. Modern Chivalry presents to us with a strange twilight era, the age of the French and Indian War, Pontiac’s Rebellion, and the Whiskey Rebellion. The novel shows Pittsburgh on the edge of civilization, when the frontier began to burn its way west to the Pacific, a liminal Pittsburgh neither totally east nor west (as indeed it remains so today).

2. The Gospel of Wealth by Andrew Carnegie (1892)

Pittsburghers have a strange relationship to the generation of men who made the city one of the wealthiest metropolises in the country (and indeed whose accumulated inherited wealth in part helped the city survive the collapse of industry). Names like Carnegie, Frick, Mellon, Westinghouse, and Heinz adorn museums, universities, schools, parks, and churches. Yet an appreciation is tempered by a certain working class suspicion; the hike is short from Henry Clay Frick’s opulent Clayton estate at the edge of the park named for him to the spot on the Monongahela across from where Pinkertons killed nine striking steelworkers in 1891. Carnegie occupies a complicated place in the psyche of the city, a poor Scottish immigrant whose life story is uncomfortably close to the bootstrap mythos of his adopted nation. Carnegie wasn’t simply the richest man in the world, but also one of the most generous philanthropists the country ever produced. A socialist in his youth, Carnegie eventually argued that redistributive justice through either labor unions or state intervention was unnecessary, and rather it was the paternal responsibility of the great man of industry to support his working brother. And so a thousand libraries bloomed, whether workers wanted them or not (raises in pay and better working conditions were another matter). In The Gospel of Wealth he puts forward his philosophy of philanthropy, one that was perhaps generous, but also very firmly on his terms (and sometimes not so transparently to his benefit as well). His bearded, kindly face peers out of a bronzed statue in the lobby of the music hall that bears his name, his shockingly small stature giving him an elfin appearance. There is an ambivalence surrounding him -- gratitude for the sheer amount of good he contributed with his wealth, but also the feeling that it was a fire escape used to ameliorate guilt he felt over things like his deputy Frick’s handling of the Homestead steel strike (not to mention the role both played in the tragic Johnstown Flood). Despite it all, there is something avuncular about his still-ghostly presence as Pittsburgh’s tiny Scottish uncle, who must feel some gratitude that we’re the only people west of Edinburgh able to pronounce his name correctly (emphasis on that first syllable).

3. “Paul’s Case” by Willa Cather in The Troll Garden (1905)

While most associated with the weather-beaten plains of her adopted Nebraska explored in novels like O Pioneers! (1913) and then the scorched deserts of New Mexico in Death Comes for the Archbishop (1927), Cather made Pittsburgh her home for 10 years. She explored the city in several short stories, most famously in her poignantly heartbreaking “Paul’s Case.” A landmark in American queer writing, “Paul’s Case” follows the attempted escape of its titular character, a sensitive adolescent aesthete who is oppressed by the Protestant work ethic of his father that permeates everything as completely as the industrial exhaust clinging blackly to every building’s exterior. Yet an opera performance at Pittsburgh’s Carnegie Hall indicates to the young man that a different manner of being is possible. He absconds with stolen money from his father and spends a week living the life of a refined sophisticate in New York City. When his father comes to retrieve him, rather than return home, Paul commits suicide by jumping in front of a train bound for Pennsylvania. A work of nuanced sophistication, “Paul’s Case” captures Pittsburgh at its dreary, industrial height, and connects the regimented, clock-work like rationalism of its factories to the oppressive strictures of the Calvinism that justified the dour capitalism of the era. In this context Paul’s rebellion, though tragic, is not a failure, for in the music halls of this gray city he was able to see a different world, even if he couldn’t make that world his home.

4. The Autobiography of Alice B. Toklas by Gertrude Stein (1933)

Her name conjures images of Left Bank bohemianism, of late-night absinthe and hash-fueled salons in her parlor, of the Seine slinking through Paris. Yet despite being the veritable mayor of the expat Lost Generation, the first river Stein would have known was not the Seine but the Allegheny. Born to a family of wealthy German Jews in Allegheny, Penn., (which is now Pittsburgh’s Northside), she was of the same community that fostered families like the Kaufmanns, once famous for their now-defunct department store chain and primarily associated with their glorious Frank Lloyd Wright house at Fallingwater. Allegheny was to Pittsburgh as Brooklyn was to New York, and as both were in some sense forcibly annexed by their larger neighbors, a certain independence still lingers in both places today. Stein reflected little on her short Pittsburgh childhood (the family moved to Oakland), and yet in the ghostwritten voice of her lover Alice B. Toklas, she wrote, “As I am an ardent Californian and as she spent her youth there I have often begged her to be born in California but she has always remained firmly born in Allegheny, Pennsylvania. She left it when she was six months old and has never seen it again and now it no longer exists being all of it Pittsburgh.”

5. Out of This Furnace by Thomas Bell (1941)

Although today the adjacent city of Braddock is primarily known for a maudlin (and yet still moving) Levi’s ad and its imposing shaven-head mayor John Fetterman, it was once the site of the Edgar Thompson Steelworks, the first Bessemer process steel mill in the world. (It should be said that portions of the mill are still in operation, despite the city losing 90 percent of its population from its historic height). That industrial site is the setting for Thomas Bell’s (ne’ Adalbert Thomas Belejcak) working class epic about Slovakian, Lemko, and Hungarian mill workers from the late 19th century through the mid-20th. Alongside other marginalized modernist authors like Tillie Olsen and Pietro di Donato, Bell offered an unsparing and unsentimental portrait of the brutality of work, alongside the often-insurmountable bigotry directed towards immigrants. Bell eschews any sort of romanticism, and Out of This Furnace is not social realist agitprop, but it is a clear-eyed depiction of the sort of violence that unregulated capitalism can enact on individuals and their communities. Throughout what emerges is a sober defense of labor rights and unionization in ensuring that the American dream is equitably available to all.

6. Pittsburgh: The Story of an American City by Stefan Lorant (1964)

Pittsburgh has the appearance of a love-child produced after a drunken one-night stand between San Francisco and Detroit. This is a compliment. Carved by three rivers cutting through the Allegheny Mountains, the city has a dramatic vista that is endlessly commented on in Pittsburgh and perennially surprises newcomers. The combination of a modern metropolis nestled among the river-kissed valleys and mountains gives the entire place a profoundly different feel from other similarly sized cities. With the iconic inclines on Mt. Washington, or the sudden conjuring of the cityscape like a mirage onto one’s field of vision as it emerges from behind the rural hills dotting I-79 North, the skyline is consistently ranked one of the most beautiful in America. Hungarian journalist Stefan Lorant worked with Life magazine photographer W. Eugene Smith to produce this massive album of Pittsburgh at mid-century, during the middle of what has been called “Renaissance I.” This civic improvement project, initiated by progressive mayor David L. Lawrence and banker Richard K. Mellon was in large responsible for beautifying the city, pushing for environmental initiatives to clean up the famously Gotham-like grime of the region, and to inaugurate massive building projects. Lorant and Smith’s massive project resulted in a text, that while suspiciously looking like a coffee table book, was perhaps one of the most comprehensive recordings of a mid-sized American city ever accomplished. Perennially popular (and going through several more editions), Pittsburgh: The Story of an American City chronicled in exacting and gorgeous detail everything from the Fifth Avenue mansions on Millionaire’s Row to the brick row houses of Bloomfield and Lawrenceville. It remains endlessly fascinating.

7. About Three Bricks Shy: And the Load Filled Up by Roy Blount Jr. (1974)

Western Pennsylvania was the forge that created Joe Montana, Johnny Unitas, Mike Ditka, Dan Marino, and Joe Namath. Football, from its glories to its toxicity, is religion in Pittsburgh. To fully explain that world requires someone familiar with the doctrine and sacraments of said religion, which the Steelers found in Southern writer Roy Blount Jr., an inhabitant of the only region in American perhaps more football obsessed than Pittsburgh. His About Three Bricks Shy: And the Load Filled Up disproves George Plimpton’s assertion that the smaller the ball, the better the sports writing. A classic of the genre, Blount’s account follows the exploits of the team before the Steel Curtain juggernaut of the late-'70s. The glory days of four Super Bowls in six years was still in the future. But the ingredients were all there: Terry Bradshaw as quarterback; the brilliant coach Chuck Noll; running backs Rocky Bleier and John “Frenchy” Fuqua; defensive lineman L.C. Greenwood; defensive back Mel Blount; and the running back Franco Harris (along with his famed “Italian Army”), who one year before accomplished the greatest play in football history with his “Immaculate Reception” (so named in the honking yinzer accent of sportscaster Myron Cope). Blount depicts a team on the verge of greatness, where all the pieces should work together, but just don’t quite do so yet. Presided over by the stodgy yet beloved Irish-Catholic owner Art Rooney Sr., Blount’s book is fascinating for depicting a team right before they would become the high priests of this strange Pittsburgh religion of football.

8. The Philosophy of Andy Warhol (From A to B & Back Again) by Andy Warhol (1975)

The city could be cold to an eccentric boy like Warhol, but in college at Carnegie Tech he was able to find a community of like-minded artistic compatriots and even mythically contributed a hidden mural to Holiday, now-closed but once the city’s oldest gay bar. With his degree in design, he escaped like Willa Cather’s Paul to New York and supposedly never looked back (though he was buried in the South Hills, his grave littered with Campbell Soup cans from admirers). Yet Andrew Warhola was a good Slovakian Catholic, attending Mass everyday with his mother, even as an adult. She took her son to the Church of St. John Chrysostom when he was an awkward, shy, St. Vitus’s dance afflicted boy. In the Byzantine Catholic splendor of the cathedral in Four Mile Run (the veritable basement of the city, bisected by the Parkway East), he would have marveled at icons of the church’s namesake and the Patristic fathers. In adulthood what did he do but invent a new form of icon based not around Christianity but America’s new religion of capitalism and celebrity, the Virgin Mary replaced with Marilyn Monroe, St. Monica with Jackie O? The city is now home to a large museum devoted to the artist, even though he had a reputation for obscuring his Pittsburgh roots. Indeed The Philosophy of Andy Warhol (From A to B & Back Again) strangely incorrectly claims the distinctly less glamorous McKeesport as his hometown. In another interview, he claimed, “I come from nowhere.” And yet an affection for the city in some sense always remained. When David Bowie played him in the film Basquiat (1996), he speaks of the Architecture Hall at the Carnegie Museum of Art where he once took classes: “Hey, we could go to Pittsburgh! I kinda grew up there. They have this room with all the world's famous statues in it, so you don't even have to go to Europe any more...just go to Pittsburgh.” Indeed the Northside is still home to Paul Warhola Scrap Metal Inc., run by Andy’s nephew who inherited it from his father, and only a few blocks away from the fashionable art museum baring his uncle’s name. Warhol may have made his career in New York, but he was always a Pittsburgher to the core, another Catholic son of mill hunkies working in a Factory.

9. Hiding Place by John Edgar Wideman (1981)

Although also associated with that other Pennsylvania city to the east where several of his books are set, Pittsburgh is still very much John Edgar Wideman’s town. A writer’s writer who has never claimed the mass readership he deserves (though he certainly has received the prizes, including a PEN/Faulkner award -- twice) Wideman chronicled the defeats and triumphs of Pittsburgh’s black neighborhood of Homewood. His novel Hiding Place was rereleased by the University of Pittsburgh Press in 1992 sandwiched between his short story collection Damballah (1981) and the novel Sent for you Yesterday (1983) under the title The Homewood Books. Wideman writes in the tradition of Sherwood Anderson, or Jean Toomer, with an understanding of the deep roots (or tentacles) that tie us to our place of origin. Damballah, named about the Haitian Loa of both creation and death, is a magical realist inflected story about Homewood’s semi-mythic creation. Wideman’s works set in Pittsburgh connect the antebellum South, legacies of slavery and intuitional racism, the Great Migration of African Americans to the industrial North, and modern urban blight. In his telling, the runaway slave Sybil Owens founds the neighborhood in the 1840s, her very name conjuring the Sibylline Oracles, a conflation of hoodoo myth and Western classicism. Wideman understands that in life and in fiction the network of interconnection between disparate elements is the very substance of life. One character reflecting on stories told to him by his aunt says, “I heard her laughter, her amens, and can I get a witness, her digressions, the web she spins and brushes away with her hands. Her stories exist because of their parts and each part is a story worth telling, worth examining to find the stories it contains.” For Wideman, storytelling is an act of personal etymology, a way of excavating the repressed history (both individual and national), of cleaning off that which has accrued to your soul.

10. Fences by August Wilson (1983)

Unsurpassed in scope, Wilson wrote 10 plays for each decade of the 20th century, nine of which are focused on the historically black Pittsburgh neighborhood of the Hill District. He has been celebrated with two Pulitzer Prizes, his name in marquees lights on a Broadway theater, a museum in Pittsburgh, and soon a Denzel Washington–produced series based on the entire cycle to appear on HBO. Born to a black mother who moved north in the Great Migration from North Carolina and a German immigrant father, Wilson was a master of code switching with an ear for American vernacular that surpasses David Mamet. In depicting the denizens of Wylie and Centre Avenues some characters reoccur, such as the supernatural Aunt Esther, a “washer of souls” who is already 285 years old at the time of Gem of the Ocean (2003), the first play in the cycle set in the 1900s. Across plays like Jitney (1982), The Piano Lesson (1987), and King Hedley II (1999), he explores painful issues of race and class in a way no playwright has before or since. Composed out of chronological order, The Pittsburgh Cycle in its entirely allows audiences to explore the relationships between space and time in the production of a particular place. Although grounded in the concrete streets of the Hill, he’s able to focus that vision out in a universal manner. Wilson takes the encyclopedic vastness of the great explorers of location, like James Joyce and William Faulkner, and weds it to performed drama. In the mouths of his characters, the Hill is animated on stage in a way few other places have ever been in the theater. Fences, set in the '50s, is arguably the most celebrated play of the cycle, winning both a Pulitzer and a Tony, and starring James Earl Jones in its Broadway premiere. Focusing on Troy, a once promising baseball player who didn’t break into the Negro League and who now works as a garbage man, the play’s themes of middle-aged despair and infidelity lend it a universal quality despite being set in a particular time and place (one that is perhaps distant from those in the audience, especially people lucky enough to be in the expensive seats). As Wilson said about the play, audiences see in Troy “love, honor, beauty, betrayal, duty,” and can begin to understand that “these things are as much part of his life as theirs.”

11. An American Childhood by Annie Dillard (1985)

Although she grew up only a 20-minute bus ride from the neighborhood depicted in The Pittsburgh Cycle, Dillard’s upbringing was one of privilege, which she explores in this memoir. She calls her childhood neighborhood of Point Breeze the “Valley of the Kings,” after the Egyptian necropolis of the pharaohs. Though by the time of her youth in the ‘50s, the area was solidly upper middle class (her father was an oil executive, and she attended the exclusive Ellis School), the remnants of its much more opulent Gilded Age past marked Point Breeze. Evidence of the tremendous wealth that shaped the city was everywhere, in robber baron mansions subdivided into apartments and the wrought-iron gate that used to be H.J. Heinz’s fence running alongside blocks of Penn Avenue. The city was built on top of itself, its history waiting to be excavated like an archeologist scouring that actual Valley of the Kings. This helped to develop Dillard’s gift for sensory detail, which she has honed into an almost theological precision. In An American Childhood she recounts how upon officially leaving the Presbyterian church as an adolescent, the minister told her that she would be back, and in many ways he was correct (if not as how he intended). Her prose (which has more than a bit of the poetic about it) adopted the sacramental poetics of a Gerard Manley Hopkins, awareness that the world is simultaneously fallen and enchanted with a charged energy. As she writes,

Skin was earth; it was soil. I could see, even on my own skin, the joined trapezoids of dust specks God had wetted and stuck with his spit the morning he made Adam from dirt. Now, all these generations later, we people could still see on our skin the inherited prints of the dust specks of Eden.

One of the most important themes of Pittsburgh literature, if we can generalize a theory of the genre, is for the possibility of transcendence in the mundane and for the sacred in the profane. Dillard may be most celebrated for bringing this awareness to her observations of the natural world in rural Virginia, but it was a spiritual skill inculcated by the contradictions of Pittsburgh, where rusting mills abut massive parks, that she first learned the personal vocabulary of matter and spirit.

12. Paradise Poems by Gerald Stern (1985)

One of the great Pittsburgh poets, Gerald Stern has diction and a personality that many would read as “New York,” which is to say as “Jewish.” Indeed (and not to conflate the regions) Stern would find himself in the unlikely position of Poet Laureate of New Jersey from 2000 to 2002. But despite his ultimate destination, Stern was very much a product of the steep, cobble-stoned streets of South Squirrel Hill, and his yiddishkeit personality of wry ironic humor and steadfast commitment to justice were very much incubated there. Many are surprised to learn that Pittsburgh is home to one of the largest urban Jewish communities in the United States, where every variety of the Jewish experience from Hasidism to socialist Zionism historically has had adherents. Often compared to his friend the former U.S. Poet Laureate Philip Levine (who similarly explored his own native city of Detroit), Stern’s verse expresses a similar industrial and Midwestern Jewish American experience. Like his other friend Gilbert, Stern would spend his life traveling and living in more exotic locations than the east end of Pittsburgh (pursuing graduate school in Paris for example). But also like Gilbert he can’t shake Pittsburgh, the language of that city permeating his speech and more importantly his consciousness. Stern’s poetry is not just introspective or confessional, but indeed sly and funny; it’s not just intellectual, but unpretentious. He is not simply wise; he is also humane. His commitments come from both a secular understanding of the Torah and the Talmud, and the working class experience of a Pittsburgh youth, what Gilbert called the “tough heaven” of the city. This is a distinctly non-utopian place where Stern argues that we must stake out our claims to utopia even within the heartbreak and discord of a broken and fallen world. This sense of not just the possibility for a restored world, but also the ethical imperative of it, is seen in his poem “The Dancing” from the collection Paradise Poems. A profound Holocaust poem, he depicts a “tiny living room / on Beechwood Boulevard” where his family celebrates the conclusion of the Second World War. Here they joyously dance to Maurice Ravel’s “Boléro,” “my hair all streaming, / my mother red with laughter, my father…doing the dance / of old Ukraine.” He calls upon the “God of mercy, oh wild God” here “In Pittsburgh, beautiful filthy Pittsburgh,” which exists in a world that can produce both the horrors of the Holocaust and the joys of dancing. Stern’s prophetic injunction is that we must live as if the world could be perfected precisely because it can’t be.

13. Mysteries of Pittsburgh by Michael Chabon (1989)

Chabon would later claim that he conceived of Mysteries of Pittsburgh as an unlikely cross between The Great Gatsby and Philip Roth’s Portnoy’s Complaint. Like both of those novels, Mysteries of Pittsburgh is a bildungsroman of sorts, a young man’s novel all the more exceptional precisely because of how young a man its author was. The book was started at the almost absurdly tender age of 21, all the more remarkable for how he deftly communicated the coming-of-age of its protagonist, Art Bechstein, and that character’s sexually confused summer after graduating from the University of Pittsburgh. A native of Columbia, Md., Chabon moved to the city as a teenager, graduating from Taylor Allderdice high school (like Stern) and studying at both CMU and Pitt. He combines both an outsider and transplant’s eye for the region, chronicling the previously underexplored reality of characters associated with the universities of the area that have increasingly come to dominate the cultural and economic life of the city as Pittsburgh transforms itself into America’s largest college town. Although acutely aware of the industrial past, Chabon’s men and women travel the leafy, Tudor-homed, middle-class streets of Shadyside and Squirrel Hill, and work in Oakland under the shadow of Pitt’s massive gothic skyscraper of a building called the Cathedral of Learning. Mysteries of Pittsburgh eschews the typical lunch-pail, shot-and-a-beer, smokestack stereotypes that linger about the city, rather portraying the tweedy, quasi-bohemian lives of writers and students (though those characters are just as likely to enjoy a boilermaker or several at that dive, the Squirrel Cage). He fuses Jewish, queer, and popular culture themes while generating characters that display a deep interiority. Both his honesty and nostalgia avoid the pitfalls of cynicism; his Pittsburgh is what it is, exhibiting a clear affection while also being aware of where it lags. This is perhaps even clearer in 1995’s Wonder Boys, arguably one of the greatest campus novels ever written, and certainly the greatest one about the Pittsburgh literary scene. It follows the weekend exploits of Professor Grady Tripp (obviously based on Pitt’s Chuck Kinder) and his brilliant student James Leer. In the narrative concerning Tripp’s demons and his sort-of-redemption, Chabon’s honesty allows us to avoid sentimentality while still offering a defense of why we read fiction at all. That doesn’t mean he can’t engage in some earthy Pittsburgh anti-pretentious shit-talking, as Tripp remarks, “There were so many Pittsburgh poets in my hallway that if, at that instant, a meteorite had come smashing through my roof, there would never have been another stanza written about rusting fathers and impotent steelworkers and the Bessemer convertor of love.”

14. The Great Fires: Poems 1982-1992 by Jack Gilbert (1994)

After winning the coveted Yale Younger Poets Prize in 1962, East Liberty’s Jack Gilbert briefly found himself celebrated as a literary wonder boy, yet he would ultimately choose what he called a “self-imposed isolation.” Though he spent a life “In Paris afternoons on Buttes-Chaumont” and “On Greek islands with their fields of stone,” he psychically remained grounded in “what remains of Pittsburgh in me.” His hometown was such an abiding subject of Gilbert's that his poetry concerning it was collected in the anthology Tough Heaven (2006), including “Searching for Pittsburgh” originally included in The Great Fires. He describes, “The rusting mills sprawled gigantically / along three rivers” and the “gritty alleys where we played every evening” that were “stained pink by the inferno always surging in the sky.” For Gilbert, Pittsburgh is “Sumptuous-shouldered, / sleek-thighed, obstinate and majestic, unquenchable” -- as perfect a description as I have ever read. This is a place of “deep-rooted grace. / A city of brick and tired wood,” with “The beauty forcing us as much as the harshness.” This catholic (lowercase c) sense of the numinous embedded even in the injustices of the world was one Gilbert witnessed first hand among the hardships but also the sublimity of working-class life in East Liberty; it allowed him to understand that “If the locomotive of the Lord runs us down, / we should give thanks that the end had magnitude” (as he wrote in his poem “A Brief for the Defense”). Central to Gilbert -- and maybe Pittsburgh writers from Stern to Dillard -- is this powerful, nostalgic, sense of loss, of an ache associated with the disappearance of things once so significant. In one of his most moving Pittsburgh poems, “Trying to Have Something Left Over,” also collected in The Great Fires, Gilbert describes entertaining the baby of his Danish mistress while the mother is occupied with chores. He writes of making the child laugh saying, “Pittsburgh softly each time before throwing him up…Pittsburgh and happiness high up. / The only way to leave even the smallest trace. / So that all his life her son would feel gladness/unaccountably when anyone spoke of the ruined / city of steel in America. Each time almost / remembering something maybe important that got lost.”

15. Muscular Music by Terrance Hayes (1999)

One of the last poems in Rita Dove’s The Penguin Anthology of Twentieth Century American Poetry was about a gay bar in Downtown Pittsburgh and was by a then–29-year-old, straight, black poet from Columbia, S.C., named Terrence Hayes. Dove included Hayes alongside poets like T.S. Eliot, Ezra Pound, Robert Frost, Sylvia Plath, John Berryman, Robert Lowell, and Allen Ginsberg as an exemplar of American verse. In what was consciously (and controversially) a cannon-defying collection, Dove choose to include Hayes as the almost-culmination of the last century of American poetry, a vote of confidence for his future significance. Across four collections, and first as a creative writing professor at Carnegie Mellon and now at Pitt, Hayes has explored race and sexuality, popular culture and personal epiphany. He is a poet for our moment, a bard for Barack Obama’s America examining issues of gender and race as lived in this moment. In “At Pegasus,” he writes of awkwardly informing one man who asks him to dance “I’m just here for the music. Even with the masculine defensiveness, he is able to tenderly reflect that he has “held / a boy on my back before. / Curtis & I used to leap / barefoot into the creek,” transporting himself from Pegasus back to a southern childhood. Considering the liberatory potential of the place, he describes the bar in distinctly Yeatsian terms with “the edge of these lovers’ gyre, /glitter & steam, fire, / bodies blurred sexless / by the music’s spinning light,” a veritable egalitarian democracy of men. He is able to empathetically link his childhood play with these men, “each breathless as a boy / carrying a friend on his back.” He explains, “These men know something / I used to know. / How could I not find them / beautiful, they way they dive & spill / into each other.” For Hayes, Pittsburgh isn’t some conservative old industrial town, but indeed a place that, however unlikely some may think, can hold a bit of emancipatory potential for those willing to look (even for outsiders).

16. One Shot Harris: The Photographs of Charles “Teenie” Harris by Deborah Willis (2002)

Pittsburgh’s African-American neighborhoods have had an outside influence on wider black culture. The Hill District would ultimately become Pittsburgh’s version of Harlem, home to jazz clubs and bars, and a center in that cultural renaissance. As the halfway point between New York and Chicago, the Pittsburgh jazz scene hosted every major musician to perform. The city also produced an unlikely array of talent, including Art Blakey; George Benson; Erroll Garner; Ahmad Jamal; Stanley Turrentine; Billy Eckstine; Lena Horne; and most notably Billy Strayhorn, Duke Ellington’s composer whose signature “Take the A Train” was based off of directions that Strayhorne received. The Hill was also home to The Pittsburgh Courier, one of the country’s oldest and most venerable black newspapers, which employed the photographer Charlie “Teenie” Harris (so nicknamed for his diminutive height). Teenie had another nickname, “One Shot,” for his borderline mythic ability to capture an almost perfect image on one try. This collection of his mid-century work curated by artist Deborah Willis gives the viewer a sense of the photographer’s scope. As the presiding archivist of the Hill, Harris took over 80,000 images, of everyone from the celebrities who traveled through (including JFK, Joe Louis, Richard Nixon, Dizzy Gillespie, Martin Luther King Jr., and dozens of others) to life in Pittsburgh’s speakeasies and black churches, from the Crawford Grill to that jazz club’s Negro League baseball team the Pittsburgh Crawfords. His massive inventory of images is perhaps the most full and complete recording of any black community in the United States, perhaps of any community at all. Archivists at the Carnegie Museum of Art are combing through the collection, identifying figures and locations. Through the entire body of work what is most conveyed is singular warmth of the people depicted even in sometimes desperate circumstances, a characteristic of the Pittsburgh aesthetic.

17. The Last Chicken in America: A Novel in Stories by Ellen Litman (2008)

Western Pennsylvania, like many parts of the industrial Midwest, has long been home to eastern European communities. Onion-domed churches punctuate the skylines of industrial towns as surely as factory smokestacks. The latest wave of immigrants arrived starting in the late-‘70s and early-‘80s, when the campaign to save Soviet Jewry resulted in the relocation of thousands of persecuted Russian Jews to the United States. In Pittsburgh many of them settled in the neighborhoods of Squirrel Hill and Greenfield, including Ellen Litman, who emigrated from Moscow in 1992, shortly after the fall of the Soviet Union. The Last Chicken in America follows her roman a clef Masha’s hybridized identity split between the Old World and New. Litman could be classifiable as part of the movement of young Russian American authors like Gary Shteyngart writing about America through the prism of their Russian backgrounds. Masha comments on the “unpleasantly wholesome smile” of a Russian friend who has assimilated a bit too readily into American culture, where that mouth now emanates “charm and fluoride, good fortune and good breeding, and you either know it’s fake and don’t trust it, or you trust it too much.” Litman’s account of first generation anxiety translates the Russian genius for ironic pessimism into a middle American vernacular. Her stories capture the storefronts of upstreet Squirrel Hill, where memories of Moscow, Leningrad, and Odessa were first discussed in Russian, then heavily accented English, then English, only to maybe eventually be forgotten. Her character Victor says, “For a true Russian person, immigration is death. A Russian poet can’t survive in immigration.” The novel’s position is agnostic on Victor’s claims, and yet it affirms that the truth of being a hyphenated American can be as contradictory and difficult in 1992 as it was in 1892 (or 2016).

18. The Bend of the World by Jacob Bacharach (2014)