Mentioned in:

A Year in Reading: 2024

Welcome to the 20th (!) installment of The Millions' annual Year in Reading series, which gathers together some of today's most exciting writers and thinkers to share the books that shaped their year. YIR is not a collection of yearend best-of lists; think of it, perhaps, as an assemblage of annotated bibliographies. We've invited contributors to reflect on the books they read this year—an intentionally vague prompt—and encouraged them to approach the assignment however they choose.

In writing about our reading lives, as YIR contributors are asked to do, we inevitably write about our personal lives, our inner lives. This year, a number of contributors read their way through profound grief and serious illness, through new parenthood and cross-country moves. Some found escape in frothy romances, mooring in works of theology, comfort in ancient epic poetry. More than one turned to the wisdom of Ursula K. Le Guin. Many describe a book finding them just when they needed it.

Interpretations of the assignment were wonderfully varied. One contributor, a music critic, considered the musical analogs to the books she read, while another mapped her reads from this year onto constellations. Most people's reading was guided purely by pleasure, or else a desire to better understand events unfolding in their lives or larger the world. Yet others centered their reading around a certain sense of duty: this year one contributor committed to finishing the six Philip Roth novels he had yet to read, an undertaking that he likens to “eating a six-pack of paper towels.” (Lucky for us, he included in his essay his final ranking of Roth's oeuvre.)

The books that populate these essays range widely, though the most commonly noted title this year was Tony Tulathimutte’s story collection Rejection. The work of newly minted National Book Award winner Percival Everett, particularly his acclaimed novel James, was also widely read and written about. And as the genocide of Palestinians in Gaza enters its second year, many contributors sought out Isabella Hammad’s searing, clear-eyed essay Recognizing the Stranger.

Like so many endeavors in our chronically under-resourced literary community, Year in Reading is a labor of love. The Millions is a one-person editorial operation (with an invaluable assist from SEO maven Dani Fishman), and producing YIR—and witnessing the joy it brings contributors and readers alike—has been the highlight of my tenure as editor. I’m profoundly grateful for the generosity of this year’s contributors, whose names and entries will be revealed below over the next three weeks, concluding on Wednesday, December 18. Be sure to subscribe to The Millions’ free newsletter to get the week’s entries sent straight to your inbox each Friday.

—Sophia Stewart, editor

Becca Rothfeld, author of All Things Are Too Small

Carvell Wallace, author of Another Word for Love

Charlotte Shane, author of An Honest Woman

Brianna Di Monda, writer and editor

Nell Irvin Painter, author of I Just Keep Talking

Carrie Courogen, author of Miss May Does Not Exist

Ayşegül Savaş, author of The Anthropologists

Zachary Issenberg, writer

Tony Tulathimutte, author of Rejection

Ann Powers, author of Traveling: On the Path of Joni Mitchell

Lidia Yuknavitch, author of Reading the Waves

Nicholas Russell, writer and critic

Daniel Saldaña París, author of Planes Flying Over a Monster

Lili Anolik, author of Didion and Babitz

Deborah Ghim, editor

Emily Witt, author of Health and Safety

Nathan Thrall, author of A Day in the Life of Abed Salama

Lena Moses-Schmitt, author of True Mistakes

Jeremy Gordon, author of See Friendship

John Lee Clark, author of Touch the Future

Ellen Wayland-Smith, author of The Science of Last Things

Edwin Frank, publisher and author of Stranger Than Fiction

Sophia Stewart, editor of The Millions

A Year in Reading Archives: 2023, 2022, 2021, 2020, 2019, 2018, 2017, 2016, 2015, 2014, 2013, 2011, 2010, 2009, 2008, 2007, 2006, 2005

The Great Fall 2024 Book Preview

With the arrival of autumn comes a deluge of great books. Here you'll find a sampling of new and forthcoming titles that caught our eye here at The Millions, and that we think might catch yours, too. Some we’ve already perused in galley form; others we’re eager to devour based on their authors, plots, or subject matters. We hope your next fall read is among them.

—Sophia Stewart, editor

October

Season of the Swamp by Yuri Herrera, tr. Lisa Dillman [F]

What it is: An epic, speculative account of the 18 months that Benito Juárez spent in New Orleans in 1853-54, years before he became the first and only Indigenous president of Mexico.

Who it's for: Fans of speculative history; readers who appreciate the magic that swirls around any novel set in New Orleans. —Claire Kirch

The Black Utopians by Aaron Robertson [NF]

What it is: An exploration of Black Americans' pursuit and visions of utopia—both ideological and physical—that spans the Reconstruction era to the present day and combines history, memoir, and reportage.

Who it's for: Fans of Saidiya Hartman's Wayward Lives, Beautiful Experiments and Kristen R. Ghodsee's Everyday Utopia. —Sophia M. Stewart

The Third Realm by Karl Ove Knausgaard, tr. Martin Aitken [F]

What it is: The third installment in Knausgaard's Morning Star series, centered on the appearance of a mysterious new star in the skies above Norway.

Who it's for: Real Knausgaard heads only—The Wolves of Eternity and Morning Star are required reading for this one. —SMS

Brown Women Have Everything by Sayantani Dasgupta [NF]

What it is: Essays on the contradictions and complexities of life as an Indian woman in America, probing everything from hair to family to the joys of travel.

Who it's for: Readers of Durga Chew-Bose, Erika L. Sánchez, and Tajja Isen. —SMS

The Plot Against Native America by Bill Vaughn [F]

What it is: The first narrative history of Native American boarding schools— which aimed "civilize" Indigenous children by violently severing them from their culture— and their enduring, horrifying legacy.

Who it's for: Readers of Ned Blackhawk and Kathleen DuVal. —SMS

The Mighty Red by Louise Erdrich [F]

What it is: Erdrich's latest novel set in North Dakota's Red River Valley is a tale of the intertwined lives of ordinary people striving to survive and even thrive in their rural community, despite environmental upheavals, the 2008 financial crisis, and other obstacles.

Who it's for: Readers of cli-fi; fans of Linda LeGarde Grover and William Faulkner. —CK

The Position of Spoons by Deborah Levy [NF]

What it is: The second book from Levy in as many years, diverging from a recent streak of surrealist fiction with a collection of essays marked by exceptional observance and style.

Who it's for: Close lookers and the perennially curious. —John H. Maher

The Bog Wife by Kay Chronister [F]

What it's about: The Haddesley family has lived on the same West Virginia bog for centuries, making a supernatural bargain with the land—a generational blood sacrifice—in order to do so—until an uncovered secret changes everything.

Who it's for: Readers of Karen Russell and Jeff VanderMeer; anyone who has ever used the phrase "girl moss." —SMS

The Great When by Alan Moore [F]

What it's about: When an 18-year old book reseller comes across a copy of a book that shouldn’t exist, it threatens to upend not just an already post-war-torn London, but reality as we know it.

Who it's for: Anyone looking for a Sherlock Holmes-style mystery dipped in thaumaturgical psychedelia. —Daniella Fishman

The Message by Ta-Nehisi Coates [NF]

What it's about: One of our sharpest critical thinkers on social justice returns to nonfiction, nearly a decade after Between the World and Me, visiting Dakar, to contemplate enslavement and the Middle Passage; Columbia, S.C., as a backdrop for his thoughts on Jim Crow and book bans; and the Israeli-occupied West Bank, where he sees contemporary segregation in the treatment of Palestinians.

Who it’s for: Fans of James Baldwin, George Orwell, and Angela Y. Davis; readers of Nikole Hannah-Jones’s The 1619 Project and Isabel Wilkerson’s Caste, to name just a few engagements with national and racial identity. —Nathalie op de Beeck

Abortion by Jessica Valenti [NF]

What it is: Columnist and memoirist Valenti, who tracks pro-choice advocacy and attacks on the right to choose in her Substack, channels feminist rage into a guide for freedom of choice advocacy.

Who it’s for: Readers of Robin Marty’s The New Handbook for a Post-Roe America, #ShoutYourAbortion proponents, and followers of Jennifer Baumgartner’s [I Had an Abortion] project. —NodB

Gifted by Suzuki Suzumi, tr. Allison Markin Powell [F]

What it's about: A young sex worker in Tokyo's red-light district muses on her life and recounts her abusive mother's final days, in what is Suzuki's first novel to be translated into English.

Who it's for: Readers of Susan Boyt and Mieko Kanai; fans of moody, introspective fiction; anyone with a fraught relationship to their mother. —SMS

Childish Literature by Alejandro Zambra, tr. Megan McDowell [F]

What it is: A wide-ranging collection of stories, essays, and poems that explore childhood, fatherhood, and family.

Who it's for: Fans of dad lit (see: Lucas Mann's Attachments, Keith Gessen's Raising Raffi, Karl Ove Knausgaard's seasons quartet, et al). —SMS

Books Are Made Out of Books ed. Michael Lynn Crews [NF]

What it is: A mining of the archives of the late Cormac McCarthy with a focus on the famously tight-lipped author's literary influences.

Who it's for: Anyone whose commonplace book contains the words "arquebus," "cordillera," or "vinegaroon." —JHM

Slaveroad by John Edgar Wideman [F]

What it is: A blend of memoir, fiction, and history that charts the "slaveroad" that runs through American history, spanning the Atlantic slave trade to the criminal justice system, from the celebrated author of Brothers and Keepers.

Who it's for: Fans of Clint Smith and Ta-Nehisi Coates. —SMS

Linguaphile by Julie Sedivy [NF]

What it's about: Linguist Sedivy reflects on a life spent loving language—its beauty, its mystery, and the essential role it plays in human existence.

Who it's for: Amateur (or professional) linguists; fans of the podcast A Way with Words (me). —SMS

An Image of My Name Enters America by Lucy Ives [NF]

What it is: A collection of interrelated essays that connect moments from Ives's life to larger questions of history, identity, and national fantasy,

Who it's for: Fans of Ives, one of our weirdest and most wondrous living writers—duh; anyone with a passing interest in My Little Pony, Cold War–era musicals, or The Three Body Problem, all of which are mined here for great effect. —SMS

Women's Hotel by Daniel Lavery [F]

What it is: A novel set in 1960s New York City, about the adventures of the residents of a hotel providing housing for young women that is very much evocative of the real-life legendary Barbizon Hotel.

Who it's for: Readers of Mary McCarthy's The Group and Rona Jaffe's The Best of Everything. —CK

The World in Books by Kenneth C. Davis [NF]

What it is: A guide to 52 of the most influential works of nonfiction ever published, spanning works from Plato to Ida B. Wells, bell hooks to Barbara Ehrenreich, and Sun Tzu to Joan Didion.

Who it's for: Lovers of nonfiction looking to cover their canonical bases. —SMS

Blue Light Hours by Bruna Dantas Lobato [F]

What it's about: Through the emanating blue-glow of their computer screens, a mother and daughter, four-thousand miles apart, find solace and loneliness in their nightly Skype chats in this heartstring-pulling debut.

Who it's for: Someone who needs to be reminded to CALL YOUR MOTHER! —DF

Riding Like the Wind by Iris Jamahl Dunkle [NF]

What it is: The biography of Sanora Babb, a contemporary of John Steinbeck's whose field notes and interviews with Dust Bowl migrants Steinbeck relied upon to write The Grapes of Wrath.

Who it's for: Steinbeck fans and haters alike; readers of Kristin Hannah's The Four Winds and the New York Times Overlooked column; anyone interested in learning more about the Dust Bowl migrants who fled to California hoping for a better life. —CK

Innie Shadows by Olivia M. Coetzee [F]

What it is: a work of crime fiction set on the outskirts of Cape Town, where a community marred by violence seeks justice and connection; also the first novel to be translated from Kaaps, a dialect of Afrikaans that was until recently only a spoken language.

Who it's for: fans of sprawling, socioeconomically-attuned crime dramas a la The Wire. —SMS

Dorothy Parker in Hollywood by Gail Crowther [NF]

What it is: A history of the famous wit—and famous New Yorker—in her L.A. era, post–Algonquin Round Table and mid–Red Scare.

Who it's for: Owners of a stack of hopelessly dog-eared Joan Didion paperbacks. —JHM

The Myth of American Idealism by Noam Chomsky and Nathan J. Robinson [NF]

What it is: A potent critique of the ideology behind America's foreign interventions and its status as a global power, and an treatise on how the nation's hubristic pursuit of "spreading democracy" threatens not only the delicate balance of global peace, but the already-declining health of our planet.

Who it's for: Chomskyites; policy wonks and casual critics of American recklessness alike. —DF

Mysticism by Simon Critchley [NF]

What it is: A study of mysticism—defined as an experience, rather than religious practice—by the great British philosopher Critchley, who mines music, poetry, and literature along the way.

Who it's for: Readers of John Gray, Jorge Luis Borges, and Simone Weil. —SMS

Q&A by Adrian Tomine [NF]

What it is: The Japanese American creator of the Optic Nerve comic book series for D&Q, and of many a New Yorker cover, shares his personal history and his creative process in this illustrated unburdening.

Who it’s for: Readers of Tomine’s melancholic, sometimes cringey, and occasionally brutal collections of comics short stories including Summer Blonde, Shortcomings, and Killing and Dying. —NodB

Sonny Boy by Al Pacino [NF]

What it is: Al Pacino's memoir—end of description.

Who it's for: Cinephiles; anyone curious how he's gonna spin fumbling Diane Keaton. —SMS

Seeing Baya by Alice Kaplan [NF]

What it is: The first biography of the enigmatic and largely-forgotten Algerian artist Baya Mahieddine, who first enchanted midcentury Paris as a teenager.

Who it's for: Admirers of Leonora Carrington, Hilma af Klint, Frida Kahlo, and other belatedly-celebrated women painters. —SMS

Absolution by Jeff VanderMeer [F]

What it is: A surprise return to the Area X, the stretch of unforbidding and uncanny coastline in the hit Southern Reach trilogy.

Who it's for: Anyone who's heard this song and got the reference without Googling it. —JHM

The Four Horsemen by Nick Curtola [NF]

What it is: The much-anticipated cookbook from the team behind Brooklyn's hottest restaurant (which also happens to be co-owned by James Murphy of LCD Soundsystem).

Who it's for: Oenophiles; thirty-somethings who live in north Williamsburg (derogatory). —SMS

Seeing Further by Esther Kinsky, tr. Caroline Schmidt [F]

What it's about: An unnamed German woman embarks on the colossal task of reviving a cinema in a small Hungarian village.

Who it's for: Fans of Jenny Erpenbeck; anyone charmed by Cinema Paradiso (not derogatory!). —SMS

Ripcord by Nate Lippens [NF]

What it's about: A novel of class, sex, friendship, and queer intimacy, written in delicious prose and narrated by a gay man adrift in Milwaukee.

Who it's for: Fans of Brontez Purnell, Garth Greenwell, Alexander Chee, and Wayne Koestenbaum. —SMS

The Use of Photography by Annie Ernaux and Marc Marie, tr. Alison L. Strayer [NF]

What it's about: Ernaux's love affair with Marie, a journalist, while she was undergoing treatment for cancer, and their joint project to document their romance.

Who it's for: The Ernaux hive, obviously; readers of Sontag's On Photography and Janet Malcolm's Still Pictures. —SMS

Nora Ephron at the Movies by Ilana Kaplan [NF]

What it is: Kaplan revisits Nora Ephron's cinematic watersheds—Silkwood, Heartburn, When Harry Met Sally, You've Got Mail, and Sleepless in Seattle—in this illustrated book. Have these iconic stories, and Ephron’s humor, weathered more than 40 years?

Who it’s for: Film history buffs who don’t mind a heteronormative HEA; listeners of the Hot and Bothered podcast; your coastal grandma. —NodB

[millions_email]

The Philosophy of Translation by Damion Searls [NF]

What it is: A meditation on the act and art of translation by one of today's most acclaimed practitioners, best known for his translations of Fosse, Proust, et al.

Who it's for: Regular readers of Words Without Borders and Asymptote; professional and amateur literary translators alike. —SMS

Salvage by Dionne Brand

What it is: A penetrating reevaluation of the British literary canon and the tropes once shaped Brand's reading life and sense of self—and Brand’s first major work of nonfiction since her landmark A Map to the Door of No Return.

Who it's for: Readers of Christina Sharpe's Ordinary Notes and Elizabeth Hardwick's Seduction and Betrayal. —SMS

Masquerade by Mike Fu [F]

What it's about: Housesitting for an artist friend in present-day New York, Meadow Liu stumbles on a novel whose author shares his name—the first of many strange, haunting happenings that lead up to the mysterious disappearance of Meadow's friend.

Who it's for: fans of Ed Park and Alexander Chee. —SMS

November

The Beggar Student by Osamu Dazai, tr. Sam Bett [F]

What it is: A novella in the moody vein of Dazai’s acclaimed No Longer Human, following the 30-something “fictional” Dazai into another misadventure spawned from a hubristic spat with a high schooler.

Who it's for: Longtime readers of Dazai, or new fans who discovered the midcentury Japanese novelist via TikTok and the Bungo Stray Dogs anime. —DF

In Thrall by Jane DeLynn [F]

What it is: A landmark lesbian bildungsroman about 16-year-old Lynn's love affair with her English teacher, originally published in 1982.

Who it's for: Fans of Joanna Russ's On Strike Against God and Edmund White's A Boy's Own Story —SMS

Washita Love Child by Douglas Kent Miller [NF]

What it is: The story of Jesse Ed Davis, the Indigenous musician who became on of the most sought after guitarists of the late '60s and '70s, playing alongside B.B. King, Bob Dylan, John Lennon, and more.

Who it's for: readers of music history and/or Indigenous history; fans of Joy Harjo, who wrote the foreword. —SMS

Set My Heart on Fire by Izumi Suzuki, tr. Helen O'Horan [F]

What it is: Gritty, sexy, and wholly rock ’n’ roll, Suzuki’s first novel translated into English (following her story collection, Hit Parade of Tears) follows 20-year-old Izumi navigating life, love, and music in the underground scene in '70s Japan.

Who it's for: Fans of Meiko Kawakami, Ursula K. Le Guin, and Marlowe Granados's Happy Hour. —DF

Didion & Babitz by Lili Anolik [NF]

What it is: A dual portrait of Joan Didion and Eve Babitz, who are so often compared to—and pitted against—each other on the basis of their mutual Los Angeles milieu.

Who it's for: Fans or haters of either writer (the book is fairly pro-Babitz, often at Didion's expense); anyone who has the Lit Hub Didion tote bag. —SMS

The Endless Refrain by David Rowell [NF]

What it's about: How the rise of music streaming, demonitizing of artist revenue, and industry tendency toward nostalgia have laid waste to the musical landscape, and the future of music culture.

Who it's for: Fans of Kyle Chayka, Spence Kornhaber, and Lindsay Zoladz. —SMS

Every Arc Bends Its Radian by Sergio De La Pava [F]

What it is: A mind- and genre-bending detective story set in Cali, Colombia, that blends high-stakes suspense with rigorous philosophy.

Who it's for: Readers of Raymond Chandler, Thomas Pynchon, and Jules Verne. —SMS

Something Close to Nothing by Tom Pyun [F]

What it’s about: At the airport with his white husband Jared, awaiting a flight to Cambodia to meet the surrogate mother carrying their adoptive child-to-be, Korean American Wynn decides parenthood isn't for him, and bad behavior ensues.

Who it’s for: Pyun’s debut is calculated to cut through saccharine depictions of queer parenthood—could pair well with Torrey Peters’s Detransition, Baby. —NodB

Rosenfeld by Maya Kessler [F]

What it is: Kessler's debut—rated R for Rosenfeld—follows one Noa Simmons through the tumultuous and ultimately profound power play that is courting (and having a lot of sex with) the titular older man who soon becomes her boss.

Who it's for: Fans of Sex and the City, Raven Leilani’s Luster, and Coco Mellor’s Cleopatra and Frankenstein. —DF

Lazarus Man by Richard Price [F]

What it is: The former The Wire writer offers yet another astute chronicle of urban life, this time of an ever-changing Harlem.

Who it's for: Fans of Colson Whitehead's Crook Manifesto and Paul Murray's The Bee Sting—and, of course, The Wire. —SMS

Stranger Than Fiction by Edwin Frank [NF]

What it is: An astute curveball of a read on the development and many manifestations of the novel throughout the tumultuous 20th century.

Who it's for: Readers who look at a book's colophon before its title. —JHM

Letters to His Neighbor by Marcel Proust, tr. Lydia Davis

What it is: A collection of Proust’s tormented—and frequently hilarious—letters to his noisy neighbor which, in a diligent translation from Davis, stand the test of time.

Who it's for: Proust lovers; people who live below heavy-steppers. —DF

Context Collapse by Ryan Ruby [NF]

What it is: A self-proclaimed "poem containing a history of poetry," from ancient Greece to the Iowa Workshop, from your favorite literary critic's favorite literary critic.

Who it's for: Anyone who read and admired Ruby's titanic 2022 essay on The Waste Land; lovers of poetry looking for a challenge. —SMS

How Sondheim Can Change Your Life by Richard Schoch [NF]

What it's about: Drama professor Schoch's tribute to Stephen Sondheim and the life lessons to be gleaned from his music.

Who it's for: Sondheim heads, former theater kids, end of list. —SMS

The Serviceberry by Robin Wall Kimmerer [NF]

What it is: 2022 MacArthur fellow and botanist Kimmerer, an enrolled member of the Citizen Potawatomi Nation, (re)introduces audiences to a flowering, fruiting native plant beloved of foragers and gardeners.

Who it’s for: The restoration ecologist in your life, along with anyone who loved Braiding Sweetgrass and needs a nature-themed holiday gift. —NodB

My Heart Belongs in an Empty Big Mac Container Buried Beneath the Ocean Floor by Homeless [F]

What it is: A pseudonymous, tenderly comic novel of blue whales and Golden Arches, mental illness and recovery.

Who it's for: Anyone who finds Thomas Pynchon a bit too staid. —JHM

Yoke and Feather by Jessie van Eerden [NF]

What it's about: Van Eerden's braided essays explore the "everyday sacred" to tease out connections between ancient myth and contemporary life.

Who it's for: Readers of Courtney Zoffness's Spilt Milk and Jeanna Kadlec's Heretic. —SMS

Camp Jeff by Tova Reich [F]

What it's about: A "reeducation" center for sex pests in the Catskills, founded by one Jeffery Epstein (no, not that one), where the dual phenomena of #MeToo and therapyspeak collide.

Who it's for: Fans of Philip Roth and Nathan Englander; cancel culture skeptics. —SMS

Selected Amazon Reviews by Kevin Killian [NF]

What it is: A collection of 16 years of Killian’s funniest, wittiest, and most poetic Amazon reviews, the sheer number of which helped him earn the rarefied “Top 100” and “Hall of Fame” status on the site.

Who it's for: Fans of Wayne Koestenbaum and Dodie Bellamy, who wrote introduction and afterword, respectively; people who actually leave Amazon reviews. —DF

Cher by Cher [NF]

What it is: The first in a two-volume memoir, telling the story of Cher's early life and ascendent career as only she can tell it.

Who it's for: Anyone looking to fill the My Name Is Barbra–sized hole in their heart, or looking for something to tide them over until the Liza memoir drops. —SMS

The City and Its Uncertain Walls by Haruki Murakami, tr. Philip Gabriel [F]

What it is: Murakami’s first novel in over six years returns to the high-walled city from his 1985 story "Hard-Boiled Wonderland and the End of the World" with one man's search for his lost love—and, simultaneously, an ode to libraries and literature itself.

Who it's for: Murakami fans who have long awaited his return to fiction. —DF

American Bulk by Emily Mester [NF]

What it's about: Reflecting on what it means to "live life to the fullest," Mester explores the cultural and personal impacts of America’s culture of overconsumption, from Costco hauls to hoarding to diet culture—oh my!

Who it's for: Lovers of sustainability; haters of excess; skeptics of the title essay of Becca Rothfeld's All Things Are Too Small. —DF

The Icon and the Idealist by Stephanie Gorton [NF]

What it is: A compelling look at the rivalry between Margaret Sanger, of Planned Parenthood fame, and Mary Ware Dennett, who each held radically different visions for the future of birth control.

Who it's for: Readers of Amy Sohn's The Man Who Hated Women and Katherine Turk's The Women of NOW; anyone interested in the history of reproductive rights. —SMS

December

Rental House by Weike Wang [F]

What it's about: Married college sweethearts invite their drastically different families on a Cape Code vacation, raising questions about marriage, intimacy, and kinship.

Who it's for: Fans of Wang's trademark wit and sly humor (see: Joan Is Okay and Chemistry); anyone with an in-law problem.

Woo Woo by Ella Baxter [F]

What it's about: A neurotic conceptual artist loses her shit in the months leading up to an exhibition that she hopes will be her big breakout, poking fun at the tropes of the "art monster" and the "woman of the verge" in one fell, stylish swoop.

Who it's for: Readers of Sheena Patel's I'm a Fan and Chris Kraus's I Love Dick; any woman who is grateful to but now also sort of begrudges Jenny Offil for introducing "art monster" into the lexicon (me). —SMS

Berlin Atomized by Julia Kornberg, tr. Jack Rockwell and Julia Kornberg [F]

What it's about: Spanning 2001 to 2034, three Jewish and downwardly mobile siblings come of age in various corners of the world against the backdrop of global crisis.

Who it's for: Fans of Catherine Lacey's Biography of X and Joshua Cohen's The Netanyahus. —SMS

Sand-Catcher by Omar Khalifah, tr. Barbara Romaine [F]

What it is: A suspenseful, dark satire of memory and nation, in which four young Palestinian journalists at a Jordanian newspaper are assigned to interview an elderly witness to the Nakba, the violent 1948 expulsion of native Palestinians from Israel—but to their surprise, the survivor doesn’t want to rehash his trauma for the media.

Who it’s for: Anyone looking insight—tinged with grim humor—into the years leading up to the present political crisis in the Middle East and the decades-long goal of Palestinian autonomy. —NodB

The Shutouts by Gabrielle Korn [F]

What it's about: In the dystopian future, mysteriously connected women fight to survive on the margins of society amid worsening climate collapse.

Who it's for: Fans of Korn's Yours for the Taking, which takes place in the same universe; readers of Becky Chambers and queer-inflected sci-fi. —SMS

What in Me Is Dark by Orlando Reade [NF]

What it's about: The enduring, evolving influence of Milton's Paradise Lost on political history—and particularly on the work of 12 revolutionary readers, including Malcom X and Hannah Arendt.

Who it's for: English majors and fans of Ryan Ruby and Sarah Bakewell—but I repeat myself. —SMS

The Afterlife Is Letting Go by Brandon Shimoda [NF]

What it's about: Shimoda researches the mass incarceration of Japanese Americans during WWII, and speaks with descendants of those imprisoned, for this essay collection about the “afterlife” of cruelty and xenophobia in the U.S.

Who it’s for: Anyone to ever visit a monument, museum, or designated site of hallowed ground where traumatic events have taken place. —NodB

No Place to Bury the Dead by Karina Sainz Borgo, tr. Elizabeth Bryer [F]

What it's about: When Angustias Romero loses both her children while fleeing a mysterious disease in her unnamed Latin American country, she finds herself in a surreal, purgatorial borderland where she's soon caught in a power struggle.

Who it's for: Fans of Maríana Enriquez and Mohsin Hamid. —SMS

The Rest Is Silence by Augusto Monterroso, tr. Aaron Kerner [F]

What it is: The author of some of the shortest, and tightest, stories in Latin American literature goes long with a metafictional skewering of literary criticism in his only novel.

Who it's for: Anyone who prefers the term "palm-of-the-hand stories" to "flash fiction." —JHM

Tali Girls by Siamak Herawi, tr. Sara Khalili [F]

What it is: An intimate, harrowing, and vital look at the lives of girls and women in an Afghan mountain village under Taliban rule, based on true stories.

Who it's for: Readers of Nadia Hashimi, Akwaeke Emezi, and Maria Stepanova. —SMS

Sun City by Tove Jansson, tr. Thomas Teal [F]

What it's about: During her travels through the U.S. in the 1970s, Jansson became interested in the retirement home as a peculiarly American institution—here, she imagines the tightly knit community within one of them.

Who it's for: Fans of Jansson's other fiction for adults, much of which explores the lives of elderly folks; anyone who watched that documentary about The Villages in Florida. —SMS

Editor's note: We're always looking to make our seasonal book previews more useful to the readers, writers, and critics they're meant to serve. Got an idea for how we can improve our coverage? Tell me about it at sophia@themillions.com.

[millions_email]

A Year in Reading: Garth Risk Hallberg

"In the early morning on the lake sitting in the stern of the boat with his father rowing, he felt quite sure that he would never die." Ever since I turned 40—that is to say, for a week now—this final sentence of Hemingway's "Indian Camp" has been rattling around my head. When I first read it, back in college, it landed like a hard left hook, knocking me flat with recognition. (I can't be alone in this; Cormac McCarthy nicked the phrasing for the end of Blood Meridian.) Right, I thought. Exactly. But now, revisiting the end of "Indian Camp,"' I see that my younger self was missing at least half the point: It's supposed to be ironic! Of course he's going to die! In fact, maybe that's why the line has been on my mind, along with Dante's "mezzo del camin di nostra vita" and Yeats's "widening gyre" and Larkin's "long slide." For though I've managed to avoid until now the garment-rending and gnashing of teeth around birthdays ("Age ain't nothing but a number," right?) forty really does feel like a delineation. At 39, rocking the Aaliyah quote is still a youthful caprice. At 41, it's a midlife crisis.

And the fact that I'm no longer immortal would seem to raise some questions about the pursuit I've more or less given my life to: reading. Specifically, if you can't take it with you, what's the point? Indeed, I now wonder whether the bouts of reader's block I suffered in 2014 and 2017 had to do not with technological change or familial or political crisis, but with the comparatively humdrum catastrophe of getting older. Yet 2018 found me rejuvenated as a reader. Maybe there was some compensatory quality-control shift in my "to-read" pile (life's too short for random Twitter) or maybe it was just dumb luck, but nearly every book I picked up this year seemed proof of its own necessity. So you'll forgive me if I enthuse here at length.

First and foremost, about Halldór Laxness's Independent People. This Icelandic classic had been on my reading list for almost a decade, but something—its bulk, its ostensible subject (sheep farming), its mythic opening—held me back. Then, this summer, I took a copy to Maine, and as soon as Bjartur of Summerhouses blustered onto the page, the stubbornest hero in all of world literature, I was hooked. As for those sheep: This is a novel about them only in the sense that Lonesome Dove is a novel about cows. And though I love Lonesome Dove, Independent People is much the better book. Laxness's storytelling offers epic sweep and power, but also, in J.A. Thompson's stunning translation, modernist depth and daring, along with humor and beauty and pain to rival Tolstoy. In short, Independent People is one of my favorite novels ever.

Also among the best things I read in 2018 were the shorter works that padded out my northern travels: Marilynne Robinson's Housekeeping and the novels of Jenny Erpenbeck. I'm obviously late arriving to the former; there's not much I can say that you won't have heard elsewhere, or experienced yourself. (Still: the prose!) Of the latter, I can report that The End of Days is ingenious, as if David Mitchell had attempted Sebald’s The Emigrants. And that Go, Went, Gone, notwithstanding Jonathan Dee's careful gift-horse inspection in Harper's, is even better. But for my money, Erpenbeck's finest novel is Visitation, which manages to pack much of the story of 20th-century Germany into the 190-page description of a country house. In any case, Erpenbeck's writing, like Robinson's, seems built to endure.

On the nonfiction front, I spent a week this fall immersed in Thomas de Zengotita's Politics and Postmodern Theory, a heady, lucid, and ultimately persuasive philosophical recasting of nearly a half-century of academic kulturkampf. Much as Wittgenstein (who gets a chapter here) claimed to resolve certain problems of philosophy by showing them to arise from elementary confusions, de Zengotita seeks to dispel muddles over the legacy of post-structuralism and the Enlightenment thought it ostensibly dismantled. He does so by giving key 20th-century thinkers—Kristeva, Derrida, Deleuze, Judith Butler—a rereading that is rigorous, respectful, accessible, and, in important ways, against the grain. As an etiology of the current cultural situation, this book belongs on a shelf with Frederic Jameson's Postmodernism and David Harvey's The Condition of Postmodernity. And, notwithstanding its price tag, anyone who cares deeply about issues of identity and solidarity and being-in-the-world today should heed its lessons.

This was also a year when the new-fiction tables at the bookstore seemed reinvigorated. For my money, the best American novel of 2018 was Rachel Kushner's The Mars Room, whose urgent blend of social conscience and poetic vision made debates about "reality hunger" and the value of fiction seem not just quaint but fallacious. So, too, with Mathias Énard's Compass, now in paperback in a crystalline translation by Charlotte Mandell. It would be hard to find a novel more indebted to historical reality, but in its fearless imagination, Compass turns these materials into something properly fictive, rather than factitious—and wholly Énard's own. And I'd be remiss not to mention Deborah Eisenberg's story collection Your Duck Is My Duck. Eisenberg writes the American sentence better than anyone else alive, and for anyone who’s followed these stories as they've appeared, serially, her brilliance is a given. Read together, though, they’re a jolting reminder of her continued necessity: her resistance to everything that would dull our brains, hearts, and nerves.

And then you could have made a National Book Awards shortlist this year entirely out of debuts. One of the most celebrated was Jamel Brinkley's A Lucky Man. What I loved about these stories, apart from the Fitzgeraldian grace of Brinkley's voice, was their tendency to go several steps beyond where a more timid writer might have stopped—to hurl characters and images and incidents well downfield of what the story strictly required and then race to catch up. More important than being uniformly successful, A Lucky Man is uniformly interesting. As is Lisa Halliday's Asymmetry. The "unexpected" coda, in my read, put a too-neat bow on things. I'd have enjoyed it even more as an unresolved diptych. But because the novel’s range and hunger are so vast, such asymmetries end up being vital complications of its interests and themes: artifice, power, subjectivity, and truth. They are signs of a writer who aims to do more than simply write what is within her power to know.

Any list of auspicious recent debuts should also include one from the other side of the pond: David Keenan's This Is Memorial Device (from 2017, but still). The novel presents—tantalizingly, for me—as an oral history of the postpunk scene in the Scottish backwater of Airdrie in the early 1980s, yet Keenan's psychedelic prose and eccentric emphases make it something even more. I was reminded frequently of Roberto Bolaño's The Savage Detectives, and could not fathom why this book was overlooked in the U.S. Hopefully, the publication of a follow-up For the Good Times, will change that.

It was a good year for journalism, too. I'm thinking not of Michael Wolff or (God forbid) Bob Woodward, but of Sam Anderson, the critic at large for The New York Times Magazine, and his first book, Boom Town. If there’s one thing less immediately exciting to me than sheep farming, it’s Oklahoma City, which this book promises (threatens?) to explore. On the other hand, I would read Sam Anderson on just about anything. Here, starting with the Flaming Lips, the land-rush of 1889, and the unlikely rise of the NBA’s Oklahoma City Thunder, he stages a massive detonation of curiosity, sensibility, and wonder. (Favorite sentence: "Westbrook, meanwhile, started the season Westbrooking as hard as he could possibly Westbrook.") And as with David Foster Wallace or John Jeremiah Sullivan, he leaves you feeling restored to curiosity and wonder yourself.

I'm also thinking of Pam Kelley's Money Rock, which focuses on the drug trade in 1980s Charlotte. It reminded me, in miniature, of a great book I’d read a few months earlier, David Simon's sprawling Homicide. Simon and Kelley are sure-handed when sketching the social systems within which we orbit, but what makes these books live is their feel for the human swerve—for Detective Terry McLarney of the Baltimore Homicide Squad or Lamont "Money Rock" Belton, locked up behind the crack game.

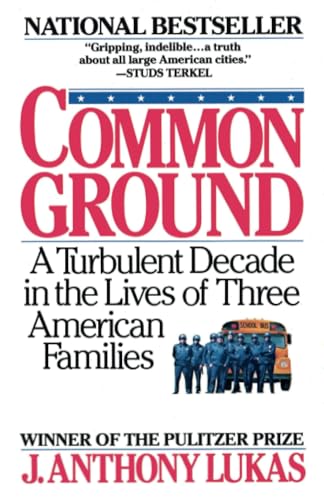

This was also the year I started reading J. Anthony Lukas, who, among the ranks of New or New-ish Journalists who emerged in the ’60s, seems to have fallen into comparative neglect. I checked out Nightmare, his book on Nixon, and was edified. Then I moved on to Common Ground, about the struggle to integrate Boston's school system, and was blown away. With little authorial commentary or judgment, but with exhaustive reporting, Lukas embeds with three families—the Waymons, the McGoffs, and the Drivers—to give us a 360-degree view of a pivotal event in American history. The book has its longeurs, but I can think of few working journalists this side of Adrian Nicole Leblanc who’d be patient enough to bring off its parallactic vision.

In talking to friends about Common Ground, I kept hearing memories of its ubiquity on the coffeetables and library shelves of the 1980s, yet no one my age seemed to have read it. Like Homicide, it hangs in that long middle age where books slowly live or die—not news anymore, but not yet old enough to fall out of print, or to become a "classic." Recommending these books feels like it might actually make a difference between the two. So here are a few more shout-outs: 1) John Lanchester, The Debt to Pleasure, from 1996. Anyone who relishes, as I do, the fundamental sanity of Lanchester's essays will be surprised by the demented glee of his first novel. Its prophetic sendup of foodie affectation throws Proust into a blender with Humbert Humbert and Patrick Suskind's Perfume—and is maybe the funniest English novel since The Information. 2) Javier Cercas, Soldiers of Salamis, from 2001. I ran down a copy in preparation for interviewing Cercas and ended up thinking this may be my favorite of his books: a story of survival during the Spanish Civil War and of an attempt to recover the truth half a century later. In it, the heroic and the mock-heroic achieve perfect balance. 3) Emma Richler, Be My Wolff, from last year. Impressed by the beauty of Richler's writing and the uncommon intelligence of her characters, I sent in a blurb for this one just under the deadline for publication, but still 50 pages from the end. When I finally got around to finishing it early this year, I found I'd missed the best part. I love this novel's passionate idiosyncrasies.

And finally...back to Scandinavia. In August, while luxuriating in Independent People, I was asked to review CoDEX 1962, a trilogy by the Icelandic writer Sjón. This in turn forced me to put aside the introduction I’d been working on for the Danish Nobel Prize-winner Henrik Pontoppidan’s magnum opus, Lucky Per...which meant a further delay in finishing Book 6 of the Norwegian Karl Ove Knausgaard’s My Struggle. With more than 3000 pages of Nordic writing before me, I felt certain warning signals flashing. As Knausgaard writes (of being 40), “Why had I chosen to organize my life this way?” The truth is that there was no organization involved, just a random clumping of the reading list, and I’m happy to report that things are now back to normal. But once I got past the anxiety, I actually enjoyed my two solid months of Nordic fiction. I wasn’t totally convinced by CoDEX 1962, but a couple of Sjón’s shorter novels killed me—especially Moonstone, a coming-of-age story set in Rekjavik in the cataclysmic early days of cinema. And though most of Pontoppidan’s corpus hasn’t been translated into English, the novellas The Royal Guest, The Polar Bear, and The Apothecary’s Daughters, make fascinating companions to Joyce, Conrad, and Chekhov...if you can find them. (Lucky Per will be republished by Everyman's Library in April.) As for Knausgaard, the final volume of My Struggle is one of the more uneven of the six, and I’m still digesting the whole. But at this point almost a decade of my life is bound up with these books. All these books, really. And that strange adjacency of real, finite life and the limitless life of the imagination...well, maybe that's been the point all along.

More from A Year in Reading 2018

Do you love Year in Reading and the amazing books and arts content that The Millions produces year round? We are asking readers for support to ensure that The Millions can stay vibrant for years to come. Please click here to learn about several simple ways you can support The Millions now.

Don’t miss: A Year in Reading 2017, 2016, 2015, 2014, 2013, 2012, 2011, 2010, 2009, 2008, 2007, 2006, 2005

[millions_ad]

‘The Blank Screen Is the Enemy’: The Millions Interviews David Mitchell

There are precious few things David Mitchell’s latest opus The Bone Clocks isn’t about. Across centuries and continents, Mitchell works the literary magic that has earned him a unique place in contemporary fiction—an author unbound by genre or expectation. The Bone Clocks was birthed onto bookshelves already longlisted for the 2014 Man Booker Prize, a daunting pedigree for a novel to embrace on its publication date, but Mitchell is already thinking two books ahead. Like the Horologists that feature in his new book, he can’t be bound by the constraints of time. Mitchell has authored six novels, and each one is a puzzle of narratives, characters, and plot. These elements leap between texts, taking minor roles in one novel and major turns in the next. The world of David Mitchell’s prose is immense. Speaking with him in person before a stop on his recent book tour, I decided to play Royal Geographic Society explorer and map out the vast expanses of his latest fictional universe.

The Millions: Do you see a book like The Bone Clocks or Cloud Atlas in part as an exercise in story architecture—dovetailing narratives, time jumps, callbacks, and so forth. How many blueprints do you need to draft before you build the final versions of your novels?

David Mitchell: An exploratory blueprint is to the finished book what a doodle might be to an oil painting, but you need somewhere to start. A vague, rough, approximate, sprawling, first something. From that you get an idea of how many parts there’s going to be—you’ve got to break it down into parts—six, in this one. Then once you know what the parts are, I draw a herringbone diagram, a horizontal line with limbs coming off it, and each limb is where I write ideas down. Each limb is essentially a scene, so you get to see all the scenes in the part and in the right order. More lines can come off the subspines—it gets quite hairy—and then a column of dialogue goes off in one direction and then another one underneath because there’s more space down there and then I might draw the face of a character because I’m stuck for a bit. That is the blueprint for what I write. What I end up writing may conform to that blueprint, or it may vary from it, but at least you are not dealing with a void. The blank screen is the enemy. You can’t improve on nothing. You have to improve on something, however bad, and patchy, and incomplete it is. Once you have something, you begin to work.

TM: The Bone Clocks deals with Atemporals, who are beings that either reincarnate or never truly die. In creating the Atemporals, you either appropriated or invented words like “scansion” and “psychosoterica”. What is the etymology of this vocabulary?

DM: Some Jung. Some what I imagine might be Greek, but I don’t speak any, so it’s only an imagined Greek. Some 21st century West Coast computer talk—some IT terms. “Redact” is probably a mid-20th century term. I see it in the Cold War sense: the redacting of documents.

TM: It immediately conjures an image of thick black lines on legal papers.

DM: Exactly. “Psychosoterica” I thought about long and hard. It is a relatively modern version of an old occult practice in the cosmology of the book. The Anchorites have fallen into a branch of the occult called The Shaded Way and the Horologists have followed a less predatory version called The Deep Stream. I made those terms up. I suppose there are echoes of how western Buddhism names the various branches of Buddhism, of which there are many. It is not a religion of the text, or a single book, that lays down the rules. It has morphed in many parts of the world into contradictory sets of beliefs in many areas, such as what happens to us after we die. A Sri Lankan Buddhist would give a very different answer then a Zen Buddhist. The thing I like about it is…that’s ok. No one has a real problem with it; they don’t go to war with each other about it.

TM: Your book features five narrators across six distinct novellas, with each section leaping forward a decade or so from the last. How did you decide what not to include from the missing years between each section?

DM: What would have skewed the novel. That’s what I left out. What would have stopped the novel taking off. I omitted what would have bent it out of shape. Watching what you’re making is what informs you about what you can and can’t include.

TM: A novelist, Crispin Hershey, narrates the third section of The Bone Clocks. In writing the character, did you gift him any of your creative leftovers like rejected book titles or abandoned story ideas?

DM: No, I think made everything up just for him, because he isn’t me. Well,he is me in terms of where the raw material comes from, but he’s a slave to his vanity in a way I try not to be. And that’s what generates, say, book titles I wouldn’t choose for my own. He’s a fictional creation and his oeuvre is tailored for him. It’s a bespoke oeuvre with him in mind.

TM: Holly Sykes is the heroine of your book, appearing in some form in each of its six segments, beginning in 1984, and stretching to 2034. How do you keep a character’s voice consistent across that time span while still allowing it to evolve with age?

DM: You are right in identifying a technical challenge. You do have to do that. The nature of the challenge changes a little big depending on what decade of her life she’s in, and what decade of the world’s life she’s in as well. First in the 1980s, you have to include a few 80s-isms and make sure that no recent developments in English slip into what Holly is saying. For example, “that’s so not what I’m going to do Mum.” We didn’t say that in the 80s. “So” was not an adjectival modifier in that sense. You make it decade appropriate. And you do that for all of the characters, of course. I factored in that at some point Holly got an education—a degree in Psychology—that would’ve upped her register away from demotic and more towards the hieratic. She learns to speak posher. That gives her a greater eloquence later in life. I needed her to be a writer, or at least a memoirist. I needed to enrich her relationship with language from the 1980s Holly. Alongside her own story, and in parallel to it, is the story of her relationship with language, which gets a bit richer the older she gets. She’s still using “sort of” to the very end; those are the last words of the book. I think it’s there in the first sentence as well. There are a few of those verbal tics, no matter how acrobatic with language we become, that stay with us. It’s hard to get it right, but it’s my job to get it right. If I got it wrong, it would endanger the fictional credibility of Holly, and then I’d have a broken book. So you think about it.

TM: The sixth and final portion of The Bone Clocks imagines a frighteningly possible near future in which an Endarkment has, in so many words, reset the world into barbaric times. Did any specific sources inspire your vision of how the world may look in twenty years?

DM: Any copy of a relatively highbrow newspaper will do it. I can’t remember exactly which news stories—it’s been a lousy summer for news, with Palestine and ISIS and Ukraine—just monstrous this year, but I’m sure there were equivalents last year too that bled into it. Actually, I read a really good book published in the 1950s called The Death of Grass, where a killer virus doesn’t kill us, humans, as they do in many contemporary stories, but it gets the crops we eat. That’s more interesting to me. Wholesale zombie apocalypses in six days makes for a few good scenes in movies, but we’ve seen those films already. But when food becomes scarcer and scarcer, and it’s moving closer and closer to your part of the world, and first rice goes, but it’s ok, because we’ve still got wheat, and then wheat turns into a brown mush in the fields, and then barley, and then oats, and then everything? Christ, what are you going to eat? What are you going to feed the animals? It gets very serious very quickly, but not so quickly that you can’t have interesting metaphysical discourse along the way. Another book, the one that Holly is reading to the kids in the last section, is The Eagle of the Ninth series by Rosemary Sutcliff. She was an English, wheelchair-bound classicist in the 1950s who wrote about the Romans leaving Britain and the collapse of Roman civilization. The series focuses on the power vacuums a collapse of that magnitude leaves, and how the innocents always end up having to pay more then the soldiers. Those books are colossal. They are fantastic. In the third book of the trilogy, The Lantern Bearers, the best of the three, there is a scene where the Roman ships leave the shores of Britain for the last time, and they know it’s the last time. What are they leaving behind? What’s going to happen to these people? That’s what was at the forefront of my mind—really how our world will look to my daughter as she grows—as I was writing that last section. What do you think, am I too gloomy, or might it happen?

TM: What scared me most was how possible it seemed to me, especially the idea of everyone trusting their devices to digitally store the history of their lives: their writing, their photographs, their memories. Everything that we think is safely stored on servers and drives is gone in an instant.

DM: It’s like a cyberstroke. And what about scientific research? What about the Hadron Collider stuff? Is anyone printing that out onto pieces of paper? I rather doubt it. Our grandchildrens’ lives are going to be a whole lot rougher then ours if I’m right. Let’s hope I’m wrong.

TM: Does the book on your bedside table often influence your works in progress?

DM: Yeah, usually, because I’ve chosen it to do just that. I read a book called The World Without Us about what would happen if humanity ceased to exist, and how long it would take to recover itself. Not long! I learned all sorts of things, like there is still a river flowing right through New York—there always was—but now it gets pumped out, except when it rains. But it just takes those pumps being stopped for 48 hours and there would be a river running down Fifth Avenue. I find that strangely comforting. The only problem is our plutonium dumps and deposits of radioactive material. We’ve damned ourselves to needing power grids to keep those cool and safe. When those go, you get what’s happening in Japan, in Fukushima. That would be the only disaster for nature if humans stopped existing. What a legacy to leave to our kids. How dare we. How dare we. Just so we can have our air conditioning and patio heaters. How dare we.

TM: So is it fair to say you choose reading material that vibes with what you’re writing at the moment? Some authors prescribe the opposite approach.

DM: Well I do sometimes go the opposite, because you find stuff there as well, serendipitously. And sometimes you just read great fiction to remind yourself of how high the bar needs to be. Halldór Laxness’s Independent People is a book I devoured. No tricks, just an old-school, somewhat intergenerational novel. It’s set in the poorest possible zone in the world, novelistically: Iceland. But it’s not Reykjavik. It’s Northeast Iceland. And it’s not in a town in Northeast Iceland, it’s in a valley where a farmer is trying to bring an abandoned farmhouse back to life. I was trying to work this out: what’s the most impossible thing to write about and make it interesting? There’s this particular section set in a boy’s head, a half-hour in real time, where he wakes before everyone else, in winter, and nothing could possibly happen. It’s the purest nothing I’ve ever seen encased in prose. But it’s a brilliant, fascinating scene. Laxness is a magician. That’s another reason why I sometimes choose to read something with no connection to what I’m working on. Although, it is Iceland, and Iceland makes two appearances in The Bone Clocks: Crispin Hershey goes there, and it appears not in the last section, but past the last section. That’s my one real moment of self-indulgence in the book. I hacked it down from six pages to about three, but it’s a three page essay on not thinking about Iceland. My editor said, “are you sure?” and I said “yeah, I want one place where Crispin isn’t being a jerk.” This is what he does, this is how he thinks. It lends him some credibility.

TM: The cultural phenomenon of Easter eggs—hidden references inside of books, films, etc.—permeates The Bone Clocks in the form of appearances from characters from your past novels and references to their worlds. What inspired their inclusion?

DM: They’re just the right people for the job. It’s not really inspiration—it’s that they fit and can bring good stuff with them. Hugo’s cool. He’s in a thirteenth of Black Swan Green as Jason Taylor’s obnoxious, precocious cousin. When I wrote that, and I’m sure when readers read it, you don’t think you’re ever going to see him again. He’ll just stay in that book and he’s done. But then here he is in The Bone Clocks as the joint second major character with Marinus. If anything inspires me, it might be that moment when a reader encounters a character they were sure they would never hear from again.

TM: Can readers hope to see any of the characters that were in The Bone Clocks in your future works?

DM: Yes. I’m going to do a book mostly about Marinus in the future, about what happens once she gets to Iceland, and to link that to Meronym, who’s a character at the center of Cloud Atlas. They call themselves the Prescients. That’s how she introduces herself when she arrives in a fusion-powered ship to the post-apocalyptic times and the think tank the surviving Horologists have set-up in Iceland. I’m going to do Hershey’s father as well, the filmmaker. I’m doing something short now, but my next major book, I’ll start that next year.

TM: Short like your recent Twitter story?

DM: Five Twitter stories. They won’t be on Twitter, but five stories of that length. And they’re linked. The first one is the Twitter story. That’s part one, and then two, three, four, five. Really short book. Marinus will appear in the fifth story, in her Iris Marinus form.

TM: You don’t define the title of your book until late into the story. Was this choice an exercise in delayed gratification?

DM: It’s cool, when you’ve forgotten that the title is a puzzle, to then have it explained. Delayed gratification. Ambushed gratification really.

TM: At the point where it is defined, in the fifth section I believe, there’s so much else going on that the last thing you’re worried about is the title, and then you gift it to readers right in the middle of a major action scene.

DM: That inspires me to utter an evil villain type “mwahahaha!”

TM: The Bone Clocks also has more then a few history lessons embedded in its pages. Did you opt to place Marinus and other Atemporals in areas of history that particularly appealed to you, or was the where and when secondary to the character development those scenes afforded the story?

DM: I chose them with thought. I needed Esther Little to be more ancient then the Horologists. Archeological evidence points back—I think the last time I looked it was 80,000 years—to indigenous Australians being the first inhabitants. There are few places as unaltered as Australia, so for deep time, it was good to give her that neck of the woods to call home. The Horologists that can’t chose their hosts, the ones that get reborn according to the laws of demographic probability, are most of the time Chinese. The Chinese population has always been a high fraction of the Earth’s population. Marinus is Chinese in the incarnation before she is Iris, when she’s the doctor who happens to be in England in time to treat Holly. It was almost a process of elimination, that one.

TM: Horology is defined as the art or science of measuring time, and is the name adopted by the group of Atemporals that Holly Sykes encounters early on in her life as well. Do you consider The Bone Clocks to be an extended definition of horology—an examination of an abstract concept that toes the line between science and art?

DM: There’s certainly an academic in Los Angeles who thinks that, Paul Harris, a member of the International Society of Time. Inadvertently, yes. That isn’t where I started though. Character development and narrative. Start there, and then the ideas will appear, like spores turning into mushrooms. I think time is a default theme of all novels. As is memory, as is character, as is identity. You can spot this when editors don’t know what to put on the jacket copy, so they put “a mesmerizing mediation on time and identity”. How can you write a novel that isn’t about those things? Maybe that’s a notch too high, because I needed to show time passing by, on the large-scale temporal arcs that plot the novel.

TM: Your novel reminded me in a small way of Richard Linklater’s newest film, Boyhood, where in the course of three hours, the audience watches a single actor go from adolescence to adulthood. Like Holly in your novel, you see this person at the end of their journey, and you know they’re the same character from before, but they’re nothing alike, not even physically.

DM: Realism, when done well, is more fantastical than fantasy. And you can’t dismiss it, because its happening in your own cells, in your own lives, in your own families. Reality is the ultimate trip.

Previously: In the Edges of the Maps: David Mitchell’s The Bone Clocks

A Year in Reading: Ben Dolnick

Ben Dolnick is the author of Zoology. He lives in Brooklyn with his fiancee and their dog, and is currently at work on a second book.This has been the year of short books for me. I've found my concentration running aground on long ones - even great long ones (Independent People, War and Peace, The Man Who Loved Children) - and so I've gravitated toward books of two-hundred or even fewer pages. The best have been the novels of Penelope Fitzgerald. In the past few months I've read The Gate of Angels, The Bookshop, Innocence and The Beginning of Spring, and each one is a ruthlessly efficient little miracle. Her books are full of characters who reliably say the wrong thing at precisely the wrong moment, who think only of themselves, who fail and fail again - and yet they're warm, funny, and somehow even cheering. I've got the rest of her novels stacked up on my bedside table.More from A Year in Reading 2007

Book List: 10 overseas writers we should be reading

The recently awarded international Man Booker prize (given to Ismail Kadare of Albania) inspired critic John Carey to announce in the Guardian: "If you speak Spanish or French or Italian or German or any of a dozen other languages, and walk into your local bookstore, you will ... find what is being imagined in China, what stories are being told in Korea, how the novel is being reinvented in Spain and the Scandinavian countries. But if you live in England you will find no such abundance." The same is true of the US, so I was happy to see that the Guardian had some experts put together a list of "10 overseas writers we should be reading." As a supplement to the Guardian's list, here are some of the books by these authors that appear to be available here in the StatesHarry Mulisch - Netherlands - The Discovery of Heaven, The Assault, Sigfried, The ProcedureStefan Heym - Germany - The Wandering Jew, The King David ReportCees Nooteboom - Netherlands - The Following Story, Roads to Santiago: A Modern-Day Pilgrimage Through Spain, Rituals, All Souls Day, In the Dutch MountainsMarcel Benabou - Morocco - Jacob, Menahem, and Mimoun: A Family Epic, Dump This Book While You Still Can!, Why I Have Not Written Any of My BooksHalldor Laxness - Iceland - Under the Glacier, Independent People, Iceland's Bell, Paradise Reclaimed, World Light, The Fish Can SingJuan Goytisolo - Spain - State of Siege, The Marx Family Saga, Marks of Identity, Juan the Landless, Landscapes of War: From Sarajevo to Chechnya, The Garden of SecretsJaan Kross - Estonia - Professor Martens' Departure, Czar's MadmanMarie Darrieussecq - France - Pig Tales: A Novel of Lust and Transformation, My Phantom Husband, Undercurrents, Breathing UnderwaterShen Congwen - China - Imperfect ParadiseDubravka Ugresic - Croatia - The Culture of Lies: Antipolitical Essays, Lend Me Your Character, Thank You for Not Reading: Essays on Literary Trivia, The Museum of Unconditional Surrender, In the Jaws of LifeLooks like an interesting, eclectic list. I'm intrigued by Ugresic in particular. For more Man Booker International Prize coverage check out the Literary Saloon.