Mentioned in:

A Year in Reading: 2024

Welcome to the 20th (!) installment of The Millions' annual Year in Reading series, which gathers together some of today's most exciting writers and thinkers to share the books that shaped their year. YIR is not a collection of yearend best-of lists; think of it, perhaps, as an assemblage of annotated bibliographies. We've invited contributors to reflect on the books they read this year—an intentionally vague prompt—and encouraged them to approach the assignment however they choose.

In writing about our reading lives, as YIR contributors are asked to do, we inevitably write about our personal lives, our inner lives. This year, a number of contributors read their way through profound grief and serious illness, through new parenthood and cross-country moves. Some found escape in frothy romances, mooring in works of theology, comfort in ancient epic poetry. More than one turned to the wisdom of Ursula K. Le Guin. Many describe a book finding them just when they needed it.

Interpretations of the assignment were wonderfully varied. One contributor, a music critic, considered the musical analogs to the books she read, while another mapped her reads from this year onto constellations. Most people's reading was guided purely by pleasure, or else a desire to better understand events unfolding in their lives or larger the world. Yet others centered their reading around a certain sense of duty: this year one contributor committed to finishing the six Philip Roth novels he had yet to read, an undertaking that he likens to “eating a six-pack of paper towels.” (Lucky for us, he included in his essay his final ranking of Roth's oeuvre.)

The books that populate these essays range widely, though the most commonly noted title this year was Tony Tulathimutte’s story collection Rejection. The work of newly minted National Book Award winner Percival Everett, particularly his acclaimed novel James, was also widely read and written about. And as the genocide of Palestinians in Gaza enters its second year, many contributors sought out Isabella Hammad’s searing, clear-eyed essay Recognizing the Stranger.

Like so many endeavors in our chronically under-resourced literary community, Year in Reading is a labor of love. The Millions is a one-person editorial operation (with an invaluable assist from SEO maven Dani Fishman), and producing YIR—and witnessing the joy it brings contributors and readers alike—has been the highlight of my tenure as editor. I’m profoundly grateful for the generosity of this year’s contributors, whose names and entries will be revealed below over the next three weeks, concluding on Wednesday, December 18. Be sure to subscribe to The Millions’ free newsletter to get the week’s entries sent straight to your inbox each Friday.

—Sophia Stewart, editor

Becca Rothfeld, author of All Things Are Too Small

Carvell Wallace, author of Another Word for Love

Charlotte Shane, author of An Honest Woman

Brianna Di Monda, writer and editor

Nell Irvin Painter, author of I Just Keep Talking

Carrie Courogen, author of Miss May Does Not Exist

Ayşegül Savaş, author of The Anthropologists

Zachary Issenberg, writer

Tony Tulathimutte, author of Rejection

Ann Powers, author of Traveling: On the Path of Joni Mitchell

Lidia Yuknavitch, author of Reading the Waves

Nicholas Russell, writer and critic

Daniel Saldaña París, author of Planes Flying Over a Monster

Lili Anolik, author of Didion and Babitz

Deborah Ghim, editor

Emily Witt, author of Health and Safety

Nathan Thrall, author of A Day in the Life of Abed Salama

Lena Moses-Schmitt, author of True Mistakes

Jeremy Gordon, author of See Friendship

John Lee Clark, author of Touch the Future

Ellen Wayland-Smith, author of The Science of Last Things

Edwin Frank, publisher and author of Stranger Than Fiction

Sophia Stewart, editor of The Millions

A Year in Reading Archives: 2023, 2022, 2021, 2020, 2019, 2018, 2017, 2016, 2015, 2014, 2013, 2011, 2010, 2009, 2008, 2007, 2006, 2005

The Great Fall 2024 Book Preview

With the arrival of autumn comes a deluge of great books. Here you'll find a sampling of new and forthcoming titles that caught our eye here at The Millions, and that we think might catch yours, too. Some we’ve already perused in galley form; others we’re eager to devour based on their authors, plots, or subject matters. We hope your next fall read is among them.

—Sophia Stewart, editor

October

Season of the Swamp by Yuri Herrera, tr. Lisa Dillman [F]

What it is: An epic, speculative account of the 18 months that Benito Juárez spent in New Orleans in 1853-54, years before he became the first and only Indigenous president of Mexico.

Who it's for: Fans of speculative history; readers who appreciate the magic that swirls around any novel set in New Orleans. —Claire Kirch

The Black Utopians by Aaron Robertson [NF]

What it is: An exploration of Black Americans' pursuit and visions of utopia—both ideological and physical—that spans the Reconstruction era to the present day and combines history, memoir, and reportage.

Who it's for: Fans of Saidiya Hartman's Wayward Lives, Beautiful Experiments and Kristen R. Ghodsee's Everyday Utopia. —Sophia M. Stewart

The Third Realm by Karl Ove Knausgaard, tr. Martin Aitken [F]

What it is: The third installment in Knausgaard's Morning Star series, centered on the appearance of a mysterious new star in the skies above Norway.

Who it's for: Real Knausgaard heads only—The Wolves of Eternity and Morning Star are required reading for this one. —SMS

Brown Women Have Everything by Sayantani Dasgupta [NF]

What it is: Essays on the contradictions and complexities of life as an Indian woman in America, probing everything from hair to family to the joys of travel.

Who it's for: Readers of Durga Chew-Bose, Erika L. Sánchez, and Tajja Isen. —SMS

The Plot Against Native America by Bill Vaughn [F]

What it is: The first narrative history of Native American boarding schools— which aimed "civilize" Indigenous children by violently severing them from their culture— and their enduring, horrifying legacy.

Who it's for: Readers of Ned Blackhawk and Kathleen DuVal. —SMS

The Mighty Red by Louise Erdrich [F]

What it is: Erdrich's latest novel set in North Dakota's Red River Valley is a tale of the intertwined lives of ordinary people striving to survive and even thrive in their rural community, despite environmental upheavals, the 2008 financial crisis, and other obstacles.

Who it's for: Readers of cli-fi; fans of Linda LeGarde Grover and William Faulkner. —CK

The Position of Spoons by Deborah Levy [NF]

What it is: The second book from Levy in as many years, diverging from a recent streak of surrealist fiction with a collection of essays marked by exceptional observance and style.

Who it's for: Close lookers and the perennially curious. —John H. Maher

The Bog Wife by Kay Chronister [F]

What it's about: The Haddesley family has lived on the same West Virginia bog for centuries, making a supernatural bargain with the land—a generational blood sacrifice—in order to do so—until an uncovered secret changes everything.

Who it's for: Readers of Karen Russell and Jeff VanderMeer; anyone who has ever used the phrase "girl moss." —SMS

The Great When by Alan Moore [F]

What it's about: When an 18-year old book reseller comes across a copy of a book that shouldn’t exist, it threatens to upend not just an already post-war-torn London, but reality as we know it.

Who it's for: Anyone looking for a Sherlock Holmes-style mystery dipped in thaumaturgical psychedelia. —Daniella Fishman

The Message by Ta-Nehisi Coates [NF]

What it's about: One of our sharpest critical thinkers on social justice returns to nonfiction, nearly a decade after Between the World and Me, visiting Dakar, to contemplate enslavement and the Middle Passage; Columbia, S.C., as a backdrop for his thoughts on Jim Crow and book bans; and the Israeli-occupied West Bank, where he sees contemporary segregation in the treatment of Palestinians.

Who it’s for: Fans of James Baldwin, George Orwell, and Angela Y. Davis; readers of Nikole Hannah-Jones’s The 1619 Project and Isabel Wilkerson’s Caste, to name just a few engagements with national and racial identity. —Nathalie op de Beeck

Abortion by Jessica Valenti [NF]

What it is: Columnist and memoirist Valenti, who tracks pro-choice advocacy and attacks on the right to choose in her Substack, channels feminist rage into a guide for freedom of choice advocacy.

Who it’s for: Readers of Robin Marty’s The New Handbook for a Post-Roe America, #ShoutYourAbortion proponents, and followers of Jennifer Baumgartner’s [I Had an Abortion] project. —NodB

Gifted by Suzuki Suzumi, tr. Allison Markin Powell [F]

What it's about: A young sex worker in Tokyo's red-light district muses on her life and recounts her abusive mother's final days, in what is Suzuki's first novel to be translated into English.

Who it's for: Readers of Susan Boyt and Mieko Kanai; fans of moody, introspective fiction; anyone with a fraught relationship to their mother. —SMS

Childish Literature by Alejandro Zambra, tr. Megan McDowell [F]

What it is: A wide-ranging collection of stories, essays, and poems that explore childhood, fatherhood, and family.

Who it's for: Fans of dad lit (see: Lucas Mann's Attachments, Keith Gessen's Raising Raffi, Karl Ove Knausgaard's seasons quartet, et al). —SMS

Books Are Made Out of Books ed. Michael Lynn Crews [NF]

What it is: A mining of the archives of the late Cormac McCarthy with a focus on the famously tight-lipped author's literary influences.

Who it's for: Anyone whose commonplace book contains the words "arquebus," "cordillera," or "vinegaroon." —JHM

Slaveroad by John Edgar Wideman [F]

What it is: A blend of memoir, fiction, and history that charts the "slaveroad" that runs through American history, spanning the Atlantic slave trade to the criminal justice system, from the celebrated author of Brothers and Keepers.

Who it's for: Fans of Clint Smith and Ta-Nehisi Coates. —SMS

Linguaphile by Julie Sedivy [NF]

What it's about: Linguist Sedivy reflects on a life spent loving language—its beauty, its mystery, and the essential role it plays in human existence.

Who it's for: Amateur (or professional) linguists; fans of the podcast A Way with Words (me). —SMS

An Image of My Name Enters America by Lucy Ives [NF]

What it is: A collection of interrelated essays that connect moments from Ives's life to larger questions of history, identity, and national fantasy,

Who it's for: Fans of Ives, one of our weirdest and most wondrous living writers—duh; anyone with a passing interest in My Little Pony, Cold War–era musicals, or The Three Body Problem, all of which are mined here for great effect. —SMS

Women's Hotel by Daniel Lavery [F]

What it is: A novel set in 1960s New York City, about the adventures of the residents of a hotel providing housing for young women that is very much evocative of the real-life legendary Barbizon Hotel.

Who it's for: Readers of Mary McCarthy's The Group and Rona Jaffe's The Best of Everything. —CK

The World in Books by Kenneth C. Davis [NF]

What it is: A guide to 52 of the most influential works of nonfiction ever published, spanning works from Plato to Ida B. Wells, bell hooks to Barbara Ehrenreich, and Sun Tzu to Joan Didion.

Who it's for: Lovers of nonfiction looking to cover their canonical bases. —SMS

Blue Light Hours by Bruna Dantas Lobato [F]

What it's about: Through the emanating blue-glow of their computer screens, a mother and daughter, four-thousand miles apart, find solace and loneliness in their nightly Skype chats in this heartstring-pulling debut.

Who it's for: Someone who needs to be reminded to CALL YOUR MOTHER! —DF

Riding Like the Wind by Iris Jamahl Dunkle [NF]

What it is: The biography of Sanora Babb, a contemporary of John Steinbeck's whose field notes and interviews with Dust Bowl migrants Steinbeck relied upon to write The Grapes of Wrath.

Who it's for: Steinbeck fans and haters alike; readers of Kristin Hannah's The Four Winds and the New York Times Overlooked column; anyone interested in learning more about the Dust Bowl migrants who fled to California hoping for a better life. —CK

Innie Shadows by Olivia M. Coetzee [F]

What it is: a work of crime fiction set on the outskirts of Cape Town, where a community marred by violence seeks justice and connection; also the first novel to be translated from Kaaps, a dialect of Afrikaans that was until recently only a spoken language.

Who it's for: fans of sprawling, socioeconomically-attuned crime dramas a la The Wire. —SMS

Dorothy Parker in Hollywood by Gail Crowther [NF]

What it is: A history of the famous wit—and famous New Yorker—in her L.A. era, post–Algonquin Round Table and mid–Red Scare.

Who it's for: Owners of a stack of hopelessly dog-eared Joan Didion paperbacks. —JHM

The Myth of American Idealism by Noam Chomsky and Nathan J. Robinson [NF]

What it is: A potent critique of the ideology behind America's foreign interventions and its status as a global power, and an treatise on how the nation's hubristic pursuit of "spreading democracy" threatens not only the delicate balance of global peace, but the already-declining health of our planet.

Who it's for: Chomskyites; policy wonks and casual critics of American recklessness alike. —DF

Mysticism by Simon Critchley [NF]

What it is: A study of mysticism—defined as an experience, rather than religious practice—by the great British philosopher Critchley, who mines music, poetry, and literature along the way.

Who it's for: Readers of John Gray, Jorge Luis Borges, and Simone Weil. —SMS

Q&A by Adrian Tomine [NF]

What it is: The Japanese American creator of the Optic Nerve comic book series for D&Q, and of many a New Yorker cover, shares his personal history and his creative process in this illustrated unburdening.

Who it’s for: Readers of Tomine’s melancholic, sometimes cringey, and occasionally brutal collections of comics short stories including Summer Blonde, Shortcomings, and Killing and Dying. —NodB

Sonny Boy by Al Pacino [NF]

What it is: Al Pacino's memoir—end of description.

Who it's for: Cinephiles; anyone curious how he's gonna spin fumbling Diane Keaton. —SMS

Seeing Baya by Alice Kaplan [NF]

What it is: The first biography of the enigmatic and largely-forgotten Algerian artist Baya Mahieddine, who first enchanted midcentury Paris as a teenager.

Who it's for: Admirers of Leonora Carrington, Hilma af Klint, Frida Kahlo, and other belatedly-celebrated women painters. —SMS

Absolution by Jeff VanderMeer [F]

What it is: A surprise return to the Area X, the stretch of unforbidding and uncanny coastline in the hit Southern Reach trilogy.

Who it's for: Anyone who's heard this song and got the reference without Googling it. —JHM

The Four Horsemen by Nick Curtola [NF]

What it is: The much-anticipated cookbook from the team behind Brooklyn's hottest restaurant (which also happens to be co-owned by James Murphy of LCD Soundsystem).

Who it's for: Oenophiles; thirty-somethings who live in north Williamsburg (derogatory). —SMS

Seeing Further by Esther Kinsky, tr. Caroline Schmidt [F]

What it's about: An unnamed German woman embarks on the colossal task of reviving a cinema in a small Hungarian village.

Who it's for: Fans of Jenny Erpenbeck; anyone charmed by Cinema Paradiso (not derogatory!). —SMS

Ripcord by Nate Lippens [NF]

What it's about: A novel of class, sex, friendship, and queer intimacy, written in delicious prose and narrated by a gay man adrift in Milwaukee.

Who it's for: Fans of Brontez Purnell, Garth Greenwell, Alexander Chee, and Wayne Koestenbaum. —SMS

The Use of Photography by Annie Ernaux and Marc Marie, tr. Alison L. Strayer [NF]

What it's about: Ernaux's love affair with Marie, a journalist, while she was undergoing treatment for cancer, and their joint project to document their romance.

Who it's for: The Ernaux hive, obviously; readers of Sontag's On Photography and Janet Malcolm's Still Pictures. —SMS

Nora Ephron at the Movies by Ilana Kaplan [NF]

What it is: Kaplan revisits Nora Ephron's cinematic watersheds—Silkwood, Heartburn, When Harry Met Sally, You've Got Mail, and Sleepless in Seattle—in this illustrated book. Have these iconic stories, and Ephron’s humor, weathered more than 40 years?

Who it’s for: Film history buffs who don’t mind a heteronormative HEA; listeners of the Hot and Bothered podcast; your coastal grandma. —NodB

[millions_email]

The Philosophy of Translation by Damion Searls [NF]

What it is: A meditation on the act and art of translation by one of today's most acclaimed practitioners, best known for his translations of Fosse, Proust, et al.

Who it's for: Regular readers of Words Without Borders and Asymptote; professional and amateur literary translators alike. —SMS

Salvage by Dionne Brand

What it is: A penetrating reevaluation of the British literary canon and the tropes once shaped Brand's reading life and sense of self—and Brand’s first major work of nonfiction since her landmark A Map to the Door of No Return.

Who it's for: Readers of Christina Sharpe's Ordinary Notes and Elizabeth Hardwick's Seduction and Betrayal. —SMS

Masquerade by Mike Fu [F]

What it's about: Housesitting for an artist friend in present-day New York, Meadow Liu stumbles on a novel whose author shares his name—the first of many strange, haunting happenings that lead up to the mysterious disappearance of Meadow's friend.

Who it's for: fans of Ed Park and Alexander Chee. —SMS

November

The Beggar Student by Osamu Dazai, tr. Sam Bett [F]

What it is: A novella in the moody vein of Dazai’s acclaimed No Longer Human, following the 30-something “fictional” Dazai into another misadventure spawned from a hubristic spat with a high schooler.

Who it's for: Longtime readers of Dazai, or new fans who discovered the midcentury Japanese novelist via TikTok and the Bungo Stray Dogs anime. —DF

In Thrall by Jane DeLynn [F]

What it is: A landmark lesbian bildungsroman about 16-year-old Lynn's love affair with her English teacher, originally published in 1982.

Who it's for: Fans of Joanna Russ's On Strike Against God and Edmund White's A Boy's Own Story —SMS

Washita Love Child by Douglas Kent Miller [NF]

What it is: The story of Jesse Ed Davis, the Indigenous musician who became on of the most sought after guitarists of the late '60s and '70s, playing alongside B.B. King, Bob Dylan, John Lennon, and more.

Who it's for: readers of music history and/or Indigenous history; fans of Joy Harjo, who wrote the foreword. —SMS

Set My Heart on Fire by Izumi Suzuki, tr. Helen O'Horan [F]

What it is: Gritty, sexy, and wholly rock ’n’ roll, Suzuki’s first novel translated into English (following her story collection, Hit Parade of Tears) follows 20-year-old Izumi navigating life, love, and music in the underground scene in '70s Japan.

Who it's for: Fans of Meiko Kawakami, Ursula K. Le Guin, and Marlowe Granados's Happy Hour. —DF

Didion & Babitz by Lili Anolik [NF]

What it is: A dual portrait of Joan Didion and Eve Babitz, who are so often compared to—and pitted against—each other on the basis of their mutual Los Angeles milieu.

Who it's for: Fans or haters of either writer (the book is fairly pro-Babitz, often at Didion's expense); anyone who has the Lit Hub Didion tote bag. —SMS

The Endless Refrain by David Rowell [NF]

What it's about: How the rise of music streaming, demonitizing of artist revenue, and industry tendency toward nostalgia have laid waste to the musical landscape, and the future of music culture.

Who it's for: Fans of Kyle Chayka, Spence Kornhaber, and Lindsay Zoladz. —SMS

Every Arc Bends Its Radian by Sergio De La Pava [F]

What it is: A mind- and genre-bending detective story set in Cali, Colombia, that blends high-stakes suspense with rigorous philosophy.

Who it's for: Readers of Raymond Chandler, Thomas Pynchon, and Jules Verne. —SMS

Something Close to Nothing by Tom Pyun [F]

What it’s about: At the airport with his white husband Jared, awaiting a flight to Cambodia to meet the surrogate mother carrying their adoptive child-to-be, Korean American Wynn decides parenthood isn't for him, and bad behavior ensues.

Who it’s for: Pyun’s debut is calculated to cut through saccharine depictions of queer parenthood—could pair well with Torrey Peters’s Detransition, Baby. —NodB

Rosenfeld by Maya Kessler [F]

What it is: Kessler's debut—rated R for Rosenfeld—follows one Noa Simmons through the tumultuous and ultimately profound power play that is courting (and having a lot of sex with) the titular older man who soon becomes her boss.

Who it's for: Fans of Sex and the City, Raven Leilani’s Luster, and Coco Mellor’s Cleopatra and Frankenstein. —DF

Lazarus Man by Richard Price [F]

What it is: The former The Wire writer offers yet another astute chronicle of urban life, this time of an ever-changing Harlem.

Who it's for: Fans of Colson Whitehead's Crook Manifesto and Paul Murray's The Bee Sting—and, of course, The Wire. —SMS

Stranger Than Fiction by Edwin Frank [NF]

What it is: An astute curveball of a read on the development and many manifestations of the novel throughout the tumultuous 20th century.

Who it's for: Readers who look at a book's colophon before its title. —JHM

Letters to His Neighbor by Marcel Proust, tr. Lydia Davis

What it is: A collection of Proust’s tormented—and frequently hilarious—letters to his noisy neighbor which, in a diligent translation from Davis, stand the test of time.

Who it's for: Proust lovers; people who live below heavy-steppers. —DF

Context Collapse by Ryan Ruby [NF]

What it is: A self-proclaimed "poem containing a history of poetry," from ancient Greece to the Iowa Workshop, from your favorite literary critic's favorite literary critic.

Who it's for: Anyone who read and admired Ruby's titanic 2022 essay on The Waste Land; lovers of poetry looking for a challenge. —SMS

How Sondheim Can Change Your Life by Richard Schoch [NF]

What it's about: Drama professor Schoch's tribute to Stephen Sondheim and the life lessons to be gleaned from his music.

Who it's for: Sondheim heads, former theater kids, end of list. —SMS

The Serviceberry by Robin Wall Kimmerer [NF]

What it is: 2022 MacArthur fellow and botanist Kimmerer, an enrolled member of the Citizen Potawatomi Nation, (re)introduces audiences to a flowering, fruiting native plant beloved of foragers and gardeners.

Who it’s for: The restoration ecologist in your life, along with anyone who loved Braiding Sweetgrass and needs a nature-themed holiday gift. —NodB

My Heart Belongs in an Empty Big Mac Container Buried Beneath the Ocean Floor by Homeless [F]

What it is: A pseudonymous, tenderly comic novel of blue whales and Golden Arches, mental illness and recovery.

Who it's for: Anyone who finds Thomas Pynchon a bit too staid. —JHM

Yoke and Feather by Jessie van Eerden [NF]

What it's about: Van Eerden's braided essays explore the "everyday sacred" to tease out connections between ancient myth and contemporary life.

Who it's for: Readers of Courtney Zoffness's Spilt Milk and Jeanna Kadlec's Heretic. —SMS

Camp Jeff by Tova Reich [F]

What it's about: A "reeducation" center for sex pests in the Catskills, founded by one Jeffery Epstein (no, not that one), where the dual phenomena of #MeToo and therapyspeak collide.

Who it's for: Fans of Philip Roth and Nathan Englander; cancel culture skeptics. —SMS

Selected Amazon Reviews by Kevin Killian [NF]

What it is: A collection of 16 years of Killian’s funniest, wittiest, and most poetic Amazon reviews, the sheer number of which helped him earn the rarefied “Top 100” and “Hall of Fame” status on the site.

Who it's for: Fans of Wayne Koestenbaum and Dodie Bellamy, who wrote introduction and afterword, respectively; people who actually leave Amazon reviews. —DF

Cher by Cher [NF]

What it is: The first in a two-volume memoir, telling the story of Cher's early life and ascendent career as only she can tell it.

Who it's for: Anyone looking to fill the My Name Is Barbra–sized hole in their heart, or looking for something to tide them over until the Liza memoir drops. —SMS

The City and Its Uncertain Walls by Haruki Murakami, tr. Philip Gabriel [F]

What it is: Murakami’s first novel in over six years returns to the high-walled city from his 1985 story "Hard-Boiled Wonderland and the End of the World" with one man's search for his lost love—and, simultaneously, an ode to libraries and literature itself.

Who it's for: Murakami fans who have long awaited his return to fiction. —DF

American Bulk by Emily Mester [NF]

What it's about: Reflecting on what it means to "live life to the fullest," Mester explores the cultural and personal impacts of America’s culture of overconsumption, from Costco hauls to hoarding to diet culture—oh my!

Who it's for: Lovers of sustainability; haters of excess; skeptics of the title essay of Becca Rothfeld's All Things Are Too Small. —DF

The Icon and the Idealist by Stephanie Gorton [NF]

What it is: A compelling look at the rivalry between Margaret Sanger, of Planned Parenthood fame, and Mary Ware Dennett, who each held radically different visions for the future of birth control.

Who it's for: Readers of Amy Sohn's The Man Who Hated Women and Katherine Turk's The Women of NOW; anyone interested in the history of reproductive rights. —SMS

December

Rental House by Weike Wang [F]

What it's about: Married college sweethearts invite their drastically different families on a Cape Code vacation, raising questions about marriage, intimacy, and kinship.

Who it's for: Fans of Wang's trademark wit and sly humor (see: Joan Is Okay and Chemistry); anyone with an in-law problem.

Woo Woo by Ella Baxter [F]

What it's about: A neurotic conceptual artist loses her shit in the months leading up to an exhibition that she hopes will be her big breakout, poking fun at the tropes of the "art monster" and the "woman of the verge" in one fell, stylish swoop.

Who it's for: Readers of Sheena Patel's I'm a Fan and Chris Kraus's I Love Dick; any woman who is grateful to but now also sort of begrudges Jenny Offil for introducing "art monster" into the lexicon (me). —SMS

Berlin Atomized by Julia Kornberg, tr. Jack Rockwell and Julia Kornberg [F]

What it's about: Spanning 2001 to 2034, three Jewish and downwardly mobile siblings come of age in various corners of the world against the backdrop of global crisis.

Who it's for: Fans of Catherine Lacey's Biography of X and Joshua Cohen's The Netanyahus. —SMS

Sand-Catcher by Omar Khalifah, tr. Barbara Romaine [F]

What it is: A suspenseful, dark satire of memory and nation, in which four young Palestinian journalists at a Jordanian newspaper are assigned to interview an elderly witness to the Nakba, the violent 1948 expulsion of native Palestinians from Israel—but to their surprise, the survivor doesn’t want to rehash his trauma for the media.

Who it’s for: Anyone looking insight—tinged with grim humor—into the years leading up to the present political crisis in the Middle East and the decades-long goal of Palestinian autonomy. —NodB

The Shutouts by Gabrielle Korn [F]

What it's about: In the dystopian future, mysteriously connected women fight to survive on the margins of society amid worsening climate collapse.

Who it's for: Fans of Korn's Yours for the Taking, which takes place in the same universe; readers of Becky Chambers and queer-inflected sci-fi. —SMS

What in Me Is Dark by Orlando Reade [NF]

What it's about: The enduring, evolving influence of Milton's Paradise Lost on political history—and particularly on the work of 12 revolutionary readers, including Malcom X and Hannah Arendt.

Who it's for: English majors and fans of Ryan Ruby and Sarah Bakewell—but I repeat myself. —SMS

The Afterlife Is Letting Go by Brandon Shimoda [NF]

What it's about: Shimoda researches the mass incarceration of Japanese Americans during WWII, and speaks with descendants of those imprisoned, for this essay collection about the “afterlife” of cruelty and xenophobia in the U.S.

Who it’s for: Anyone to ever visit a monument, museum, or designated site of hallowed ground where traumatic events have taken place. —NodB

No Place to Bury the Dead by Karina Sainz Borgo, tr. Elizabeth Bryer [F]

What it's about: When Angustias Romero loses both her children while fleeing a mysterious disease in her unnamed Latin American country, she finds herself in a surreal, purgatorial borderland where she's soon caught in a power struggle.

Who it's for: Fans of Maríana Enriquez and Mohsin Hamid. —SMS

The Rest Is Silence by Augusto Monterroso, tr. Aaron Kerner [F]

What it is: The author of some of the shortest, and tightest, stories in Latin American literature goes long with a metafictional skewering of literary criticism in his only novel.

Who it's for: Anyone who prefers the term "palm-of-the-hand stories" to "flash fiction." —JHM

Tali Girls by Siamak Herawi, tr. Sara Khalili [F]

What it is: An intimate, harrowing, and vital look at the lives of girls and women in an Afghan mountain village under Taliban rule, based on true stories.

Who it's for: Readers of Nadia Hashimi, Akwaeke Emezi, and Maria Stepanova. —SMS

Sun City by Tove Jansson, tr. Thomas Teal [F]

What it's about: During her travels through the U.S. in the 1970s, Jansson became interested in the retirement home as a peculiarly American institution—here, she imagines the tightly knit community within one of them.

Who it's for: Fans of Jansson's other fiction for adults, much of which explores the lives of elderly folks; anyone who watched that documentary about The Villages in Florida. —SMS

Editor's note: We're always looking to make our seasonal book previews more useful to the readers, writers, and critics they're meant to serve. Got an idea for how we can improve our coverage? Tell me about it at sophia@themillions.com.

[millions_email]

A Year in Reading: Kate Petersen

Letters. The year began with letters. Well, emails. Jokey work emails that turned, somewhere along the line, to letters—getting-to-know-you letters, then, to love letters. I began to consider paragraph breaks. Thrilled to his name in my inbox. In a smoky restaurant in Mexico City I read one letter again and again, then handed my phone to friends and asked them to read it, asked if they heard what I heard.

I had not received such

letters in many years, and was out of practice.

I had recently moved from a single room in San Francisco where the only books I could keep close were those I taught. It was a year of rediscovering books I had known and not seen in a long time. Collections of poetry I had found in the stacks of now-gone Aardvark Books, the still-there Green Apple.

In winter, I sent him poems by Joanna Klink, poems of light and frost and estuary. He checked out books of poems from the library, sent phone pictures of pages to me: Kyle Dargan. Mary Oliver.

Friends sent me other poems, ones by Maria Hummel. Jon Davis. I saved everything. My phone ran out of room.

More emails. I planned a Summit, an endeavor as big and overshadowing as the word suggests. This required many many emails. Books languished, half-read, on my coffee table. (I am reading them now: among them, Nafissa Thompson-Spires’s Heads of the Colored People, Nathaniel Rich’s Losing Earth, Peter Kline’s Mirrorforms). Too many browser tabs stayed open. Birthday cards and bills lay unsent on my desk. As if there were a different well of hours to draw from, I also worked to finish my own book. Read my own words over and over until sentences arrived to me on training runs and in dreams, and I understood they were complete.

In spring, he sat in my kitchen and read me Frank O’Hara’s “For Grace, After a Party.” Layli Long Soldier visited campus and read to us from Whereas, then a love poem from her phone.

At the beginning of summer, he found his old copy of The Wind in the Willows. ("This day was only the first of many similar ones for the emancipated Mole, each of them longer and fuller of interest as the ripening summer moved onward.")

Driving over a pass in the Rockies at the end of an August hailstorm, I read him the bewildering music of Anne Carson’s “Just for the Thrill: An Essay on the Difference Between Women and Men.” ("From the shadows run mysterious ground lines down into my apparent heart.") A story of image and estrangement, hers, but perhaps my campaign was one of foils. There we were in the same country. Were we not there to disprove her essay’s theorem?

On a stolen afternoon in fall, we packed sandwiches and library books and headed up Bear Jaw trail. Stolen from emails, I mean. High up in the aspens, I read Jane Hirshfield to him. ("If the leaves. If the rise of the fish").

On the way back from the Chicago Marathon, I bought Susan Steinberg’s Machine in the airport bookshop, Barbara’s, all while holding the largest McDonald’s ice cream cone ever dispensed at O’Hare. Please patronize Barbara’s; they were very forgiving about the ice cream cone.

After he was asleep, I read Sharon Olds to myself.

On nights he wasn’t there, I thumbed through my old books for articulation, clues to this season. I found myself turning to persona poems (like Amy Gerstler’s Ghost Girl), stories of manners, inward-turned, jar-tight stories of being a woman, or an other woman, of the mind casting around in its now ill-fitting loneliness. Renata Adler’s Pitch Dark and Laurie Colwin’s “Animal Behavior.” I let myself be devastated by tenses (here, Adler’s narrator, Kate): “You are, you know, you were the nearest thing to a real story to happen in my life.”

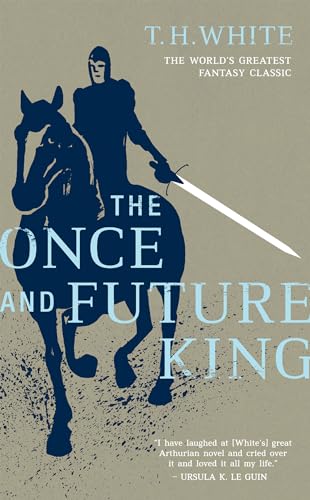

On nights he was there, he read to me from The Once and Future King, a book I taught long ago.

Well, so what? In certain houses, certain years of life, reading to someone and being read to is routine. The default even. But I had not lived in such a year, or house, for many. ("Until you brought me, casually, an hour," Klink writes.)

Then he read to me. Some nights by headlamp, or perched on a rock over Oak Creek, but most in the plain confines of my beige-walled apartment by the light of an oil lamp he’d cleaned up and given me. Year of long return. Year of song, a voice that is not yours telling you a story. Year I was let back in to the original enchantment of reading a book: a shoulder, feeling the words begin in his chest, breath held as the page turns. A light nearby, not much more than a candle, waiting to be blown out.

A Year in Reading: Laura Turner

The best book club I ever joined was one that reads exclusively from two categories: Bestselling books from several years back, and books set in the place we happen to be traveling. We meet whenever we want, read whatever we want, and eat whatever we want—mostly milk chocolate peanut butter cups from Trader Joe’s.

I am also the only member of this book club, which is either brilliant or terribly sad. I was beginning to think it was the latter until one morning in July, when, sitting on a dock at a small alpine lake in the Sierra Nevada, I realized how incredibly happy I was to be reading The Goldfinch at that moment, stuck with our heroes in Las Vegas, when all the other, self-respecting book clubs had read it four years ago, when it first came out.

If you haven’t read The Goldfinch, welcome! This is a safe space. You could call it a coming-of-age story (“bildungsroman,” if you’re nasty), and it is, but it’s also a philosophical treatise on the value of art, family, and New York City. Young Theo survives a terrorist attack at an art museum, and takes something more from the scene than what he arrived with. The best part of the book is Theo’s fever dream year in the near-empty suburbs of Las Vegas with his Russian friend, Boris, who has to be played by Adam Driver in the eventual film version. That section alone is worth the price of admission. Don’t tell me if you didn’t like the book, or if you think I’m dumb for reading it four years after its release. I had fun reading it, and this year, fun reading was hard to come by.

The only other truly fun book I read in 2017 was We’re Going to Need More Wine by Gabrielle Union, everyone’s best friend in every truly good teen movie of the '90s. Union is much more forthcoming about almost every aspect of her life than in most celebrity memoirs; as a life-long and self-proclaimed B-lister this may be because she has less to lose. She talks frankly about her sexuality as a teenage girl growing up in northern California; about being one of only two black girls at her mostly upper-middle-class high school; and her surprise at having to code-switch when she returned each summer to visit family in Omaha. She deconstructs her first marriage with an incredible amount of honesty and responsibility, and her chapter about wanting to get pregnant and having had “7, maybe 8” miscarriages after many rounds of IVF was heartbreaking, as was her account of her family’s response to her rape by a burglar at the Payless store where she worked. It’s not Marcel Proust, but then again, I’ve never really liked Proust.

Traveling through Turkey and Georgia this spring, I was eager to read some books by local authors, so when I found Motherland Hotel by Yusuf Atilgan at a bookstore, I picked it up. Set in Izmir, a port city on Turkey’s Aegean coast, the titular hotel is run by Zeberjet, whose family ran the place before him. He has no nearby relatives or family of his own, but spends his days attending to the work of running a small hotel, including a daily tryst with the sleeping housekeeper, who seems to have halfheartedly agreed to being used in this way. That all comes to an end when Zeberjet falls in love with a beautiful guest, and his obsession over her causes his days and his world to constrict to an impossibly small pinprick. He keeps the guest’s room in just the order she left it, turning out paying customers in case of her return. His descent into madness is precipitated by unexpected sexual behavior, revealing traumas from his past, and a terrible (metaphorical) claustrophobia that shuts off any possibility of a meaningful life. It’s a strange read, immersive and Kafkaesque, and hard to forget.

Prospero’s bookstore in Tblisi is enough to drive any reader to max out her credit card. I was limited by the size of my suitcase to one or three new books, and so I chose The Knight in the Panther’s Skin carefully—it was a beautiful edition but sizable, hardcover with beautiful illustrations. The book is an epic poem, written by the 12th-century Georgian poet Shota Rustaveli, (his fame is still great enough that the central avenue running north-south in Tbilisi is called Rustaveli). In this poem, two best friends (Tariel and Avtandil) go in search of Nestan-Darejan, the Helen of Troy-ish figure who was actually modeled on the Georgian Queen Tamar (a woman so badass she was occasionally referred to as “King”). In Lyn Coffin’s translation of the poem, which is essentially Lord of the Rings meets The Once and Future King with a dash of the Biblical book of Esther, we encounter a weeping knight wearing a panther’s skin (“Lost in his grief he wept, and knew not that any stood near him”) who seems to disappear into thin air. Avtandil spends three years searching for him, and finally finds him living in a cave. This is Tariel. Together, they set out to find Nestan-Darejan.

[millions_ad]

Strangely, the book takes place entirely outside of Georgia—Rustaveli sets it in Arabia, India, and China—but commentators have found in Knight an entirely Georgian vision of the world. I’m not entirely sure what that means, except that in Georgia I found the most sweeping sense of world history—the earliest hominids to be found outside of Africa were found there—alongside a warmth of spirit that was not disconnected from the warmth of appealing food, which Knight also celebrated.

My book club of one is finishing up the year with Viet Thanh Nguyen’s The Sympathizer, a book that reminds me both of Graham Greene and Joseph Heller, which is a perfect combination. There is some, um, imaginative use of squid, conflicted feelings about the protagonist’s homeland, and a lot of wandering questions about when a place really becomes home. It’s a perfect book for the end of a year that has seen me asking much of the same. Til next year!

More from A Year in Reading 2017

Do you love Year in Reading and the amazing books and arts content that The Millions produces year round? We are asking readers for support to ensure that The Millions can stay vibrant for years to come. Please click here to learn about several simple ways you can support The Millions now.

Don't miss: A Year in Reading 2016, 2015, 2014, 2013, 2012, 2011, 2010, 2009, 2008, 2007, 2006, 2005

The Case for Genre Fiction: A Guide to Literary Science Fiction and Fantasy

Is there such a thing as literary science fiction? It’s not a sub-genre that you’d find in a bookshop. In 2015, Neil Gaiman and Kazuo Ishiguro debated the nature of genre and fiction in the New Statesman. They talk about literary fiction as just another genre. Meanwhile, Joyce Saricks posits that rather than a genre, literary fiction is a set of conventions.

I’ve not read a whole lot of whatever might be defined as literary fiction. I find non-genre fiction a little on the dull side. People -- real people -- interacting in the real world or some such plot. What’s the point of that? I want to read something that in no way can ever happen to me or anyone I know. I want to explore the imagination of terrific authors. I’ve heard that literary fiction is meant to be demanding. I don’t mind demanding, but I want, as a rule, a stimulating plot and relatable or, at the very least, interesting characters. I suspect My Idea of Fun by Will Self (1993) is the closest I’ve come to enjoying a piece of literary fiction, but I was far from entertained. And so I read genre fiction -- mostly science fiction, but anything that falls under the umbrella of speculative fiction.

It turns out that some of what I’ve read and enjoyed and would recommend might be called literary science fiction. This is sometimes science fiction as written by authors who wouldn’t normally write within the genre, but more often than not regular science fiction that has been picked up by a non-genre audience. Literary fantasy is not so common as literary science fiction, but there is a lot of fantasy, both classical and modern that non-fantasy fans will be familiar with (many are put off by the label "fantasy," and maybe an awful lot of terrible 1980s fantasy movies). Of course there are J.R.R. Tolkien’s books and the Chronicles of Narnia and Virginia Woolf’s Orlando. These books are only the briefest glimpses into both the imagination of some terrific authors and the scope of fantasy fiction. It isn’t all about hobbits and lions and wizards. There’s much more to explore.

You’ve likely read most of these examples; if they’ve piqued your interest and want to explore more genre fiction, here are some suggestions for next steps.

You read:

Super Sad True Love Story (2010) by Gary Shteyngart is a grim warning of the world of social media. There’s not a whole lot of plot, but Shteyngart’s story is set in a slightly dystopic near future New York. There are ideas about post-humanism, as technology is replacing emotional judgement -- people don’t need to make choices; ratings, data, and algorithms do that for you. As an epistolary and satirical novel Super Sad True Love Story engages well. The science fiction elements are kept to the background as the characters’ relationships come to the fore.

Now try:

Ready Player One (2011) by Ernest Cline. In Cline’s near future, like Shteyngart’s, there is economic dystopic overtones. Most folk interact via virtual worlds. In the real world, most people are judged harshly. Wade spends all his time in a virtual utopia that is a new kind of puzzle game. Solving clues and eventually winning it will allow him to confront his real-world relationships. Friendships are key to the enjoyment of this novel, as well as how technology alters our perception of them. Are we the masters or servants of technology?

Snow Crash (1992) by Neal Stephenson is a complex and knowing satire. The world is full of drugs, crime, nightclubs, and computer hacking; "Snow Crash" is a drug that allows the user access to the Metaverse. Stephenson examined virtual reality, capitalism, and, importantly, information culture and its effects on us as people -- way before most other authors. Like Cline and Shtenyngart, technology -- in this case the avatars -- in Snow Crash is as much a part of the human experience as the physical person.

You read:

Never Let Me Go (2005) by Kazuo Ishiguro is one of the best and most surprising novels in the science fiction genre. It is the story of childhood friends at a special boarding school, narrated by Kathy. Slowly the world is revealed as a science fiction dystopia wherein where the privileged literally rely on these lower class of people to prolong their lives. The science fiction-ness of the story -- how the genetics work for example -- is not really the purpose of the story. Ishiguro writes brilliantly about what it means to be a person and how liberty and relationships intertwine.

Now try:

Spares (1996) by Michael Marshall Smith tells pretty much the same story, but with a different narrative and a more brutal full-on science fiction realization. Jack Randall is the typical Smith anti-hero -- all bad mouth and bad luck. He works in a Spares farm. Spares are human clones of the privileged who use them for health insurance. Lose an arm in an accident; get your replacement from your clone. Spares is dark yet witty, and again, muses on the nature of humanity, as Jack sobers up and sees the future for what it really is. He believes the Spares are people too, and that it’s time he takes a stand for the moral high ground, while confronting his past.

The Book of Phoenix (2015) by Nnedi Okorafor is another tale about what it means to be a human in a created body. A woman called Phoenix is an "accelerated human" who falls in love and finds out about the horrors perpetuated by the company that created her. One day, Phoenix’s boyfriend witnesses an atrocity and kills himself. Grieving, Phoenix decides she is in a prison rather than a home. The book is, on the surface, about slavery and oppression: Americans and their corporations taking the lives of people of color as if they meant nothing. It is powerful stuff, with very tender moments.

You read:

Slaughterhouse-Five (1969) by Kurt Vonnegut is perhaps his most famous work, and maybe his best. It is the tale of Billy Pilgrim, an anti-war chaplain's assistant in the United States Army, who was captured in 1944 and witnessed the Dresden bombings by the allies. This narrative is interweaved with Billy’s experiences of being held in an alien zoo on a planet far from Earth called Tralfamadore. These aliens can see in such a way that they experience all of spacetime concurrently. This leads to a uniquely fatalistic viewpoint when death becomes meaningless. Utterly brilliant. Definitely science fiction. So it goes.

Now try:

A Scanner Darkly (1977) by Philip K. Dick. Like Vonnegut, Dick often mixes his personal reality with fiction and throws in an unreliable narrator. In A Scanner Darkly, Bob Arctor is a drug user (as was Dick) in the near future. However, he’s also an undercover agent investigating drug users. Throughout the story, we’re never sure who the real Bob is, and what his motives are. It’s a proper science fiction world where Bob wears a "scramble suit" to hide his identity. Dick’s characters get into your head and make you ponder the nature of who you might be long after the book is over.

Little Brother (2008) by Cory Doctorow takes a look at the world of surveillance. Unlike Dick’s novel, this is not an internal examination but an external, as four teenagers are under attack from a near future Department of Homeland Security. Paranoia is present and correct as 17-year-old Marcus and his friends go on the run after a terrorist attack in San Francisco. Doctorow’s usual themes include fighting the system and allowing information to be free.

You read:

The Handmaid’s Tale (1985) by Margaret Atwood. After a religiously motivated terrorist attack and the suspension of the U.S. Constitution, the newly formed Republic of Gilead takes away some women's rights -- even the liberty to read. There is very little science in The Handmaid’s Tale -- indeed, Atwood herself calls it speculative rather than science fiction. The point, however, is not aliens or spaceships, but how people deal with the present, by transporting us to a potential, and in this case frightening, totalitarian future.

Now try:

Bête (2014) by Adam Roberts is also a biting satire about rights. Animals, in Roberts’ bleak future, have been augmented with artificial intelligence. But where does the beast end and the technology take over? The protagonist in this story is Graham, who is gradually stripped of his own rights and humanity. He is one of the most engaging protagonists in recent years: an ordinary man who becomes an anti-hero for the common good. As with The Handmaid’s Tale, the author forces us to consider the nature of the soul and self-awareness.

Herland (1915) by Charlotte Perkins Gilman explores the ideas of a feminist utopia from the perspective of three American male archetypes. More of a treatise than a novel, it is science fiction only in the sense of alternative history and human reproduction via parthenogenesis. Gilman suggests that gender is socially constructed and ultimately that rights are not something that can be given or taken from any arbitrary group.

You read:

The Left Hand of Darkness (1969) by Ursula K. Le Guin is regarded as the novel that made her name in science fiction. Humans did not originate on Earth, but on a planet called Hain. The Hainish seeded many worlds millions of years ago. In The Left Hand of Darkness, set many centuries in the future, Genly Ai from Earth is sent to Gethen -- another seeded world -- in order to invite the natives to join an interplanetary coalition. As we live in a world of bigotry, racism and intolerance, Le Guin brilliantly holds up a mirror.

Now try:

Ammonite (1992) by Nicola Griffith also addresses gender in the far future. On a planet that has seen all men killed by an endemic disease, anthropologist Marghe journeys around the planet looking for answers to the mysterious illness, while living with various matricidal cultures and challenging her own preconceptions and her identity. Griffith’s attention to detail and the episodic nature of Marghe’s life result in a fascinating and engaging story -- which is what the women of this planet value above all else. Accepting different cultural ideologies is an important factor in science fiction and both Le Guin and Griffith have produced highlights here.

The Long Way to a Small, Angry Planet (2015) by Becky Chambers. There’s a ship called the Wayfayer, crewed by aliens, who are, by most definitions, the good guys. A new recruit named Rosemary joins the ship as it embarks on a mission to provide a new wormhole route to the titular planet. Chambers writes one of most fun books in the genre, featuring aliens in love, fluid genders, issues of class, the solidarity of family, and being the outsider.

You Read:

Jonathan Strange & Mr. Norrell (2004) by Susanna Clarke. In this folk-tale fantasy, Clarke writes a morality tale set in 19th-century England concerning magic and its use during the Napoleonic Wars. Somewhat gothic, and featuring dark fairies and other supernatural creatures, this is written in the style of Charles Dickens and others. Magic is power. Who controls it? Who uses it? Should it even be used?

Now try:

Sorcerer to the Crown (2015) by Zen Cho is set in a similar universe to Clarke’s novel: Regency England with added fantasy. Women don’t have the same rights as men, and foreign policy is built on bigotry. The son of an African slave has been raised by England’s Sorcerer Royal. As in Clarke’s story, magic is fading and there are strained relationships with the fairies. This is where the novels diverge. Prunella Gentleman is a gifted magician and fights her oppressive masters. Cho writes with charm and the characters have ambiguity and depth. This is more than just fairies and magic, it is a study of human monsters, women’s rights, and bigotry.

Alif the Unseen (2012) by G. Willow Wilson. Take the idea of power, politics and traditional magic and move it to the Middle East. We’re in a Middle-Eastern tyrannical state sometime in the near future. Alif is Arabian-Indian, and he’s a hacker and security expert. While having a science fiction core, this sadly under-read book has fantasy at its heart. When Alif’s love leaves him, he discovers the secret book of the jinn; he also discovers a new and unseen world of magic and information. As with those above, this is a story of power. Who has it, and who controls it. The elite think they do, but the old ways, the old magic is stronger.

You read:

Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland (1865) by Lewis Carroll. Everyone’s favorite surrealist fantasy begins with a bored little girl looking for an adventure. And what an adventure! Dispensing with logic and creating some of the most memorable and culturally significant characters in literary history, Carroll’s iconic story is a fundamental moment not just in fantasy fiction but in all fiction.

Now try:

A Wild Sheep Chase (1982) by Haruki Murakami sees the (unreliable?) narrator involved with a photo that was sent to him in a confessional letter by his long-lost friend, The Rat. Another character, The Boss’s secretary, reveals that a strange sheep with a star shaped birthmark, pictured in an advertisement, is in some way the secret source of The Boss's power. The narrator quests to find both the sheep and his friend. Doesn’t sound much like Alice for sure, but this is a modern take on the surreal journey populated by strange and somewhat impossible characters, with a destination that might not be quite like it seems. You might have read Kafka on the Shore or The Wind-Up Bird Chronicle -- both terrific novels -- but you really should read Murakami’s brilliantly engaging exploration into magical oddness.

A Man Lies Dreaming (2014) by Lavie Tidhar. Was Alice’s story nothing more than a dream? Or something more solid? Shomer, Tidhar’s protagonist, lies dreaming in Auschwitz. Having previously been a pulp novelist, his dreams are highly stylized. In Shomer’s dream, Adolf Hitler is now disgraced and known only as Wolf. His existence is a miserable one. He lives as a grungy private dick working London's back streets. Like much of Tidhar’s work, this novel is pitched as a modern noir. It is however, as with Carroll’s seminal work, an investigation into the power of imagination. Less surreal and magical than Alice, it explores the fantastical in an original and refreshing manner.

You read:

The Once and Future King (1958) by T.H. White. A classical fantasy tale of English folklore, despite being set in "Gramarye." White re-tells the story of King Arthur, Sir Lancelot, and Queen Guinevere. This is an allegoric re-writing of the tale, with the time-travelling Merlyn bestowing his wisdom on the young Arthur.

Now try:

Redemption in Indigo (2010) by Karen Lord takes us on a journey into a Senegalese folk tale. Lord’s protagonist is Paama’s husband. Not at all bright, and somewhat gluttonous, he follows Paama to her parent’s village. There he kills the livestock and steals corn. He is tricked by spirit creatures (djombi). Paama has no choice to leave him. She meets the djombi, who gives her a gift of a Chaos Stick, which allows her to manipulate the subtle forces of the world.

A Tale for the Time Being (2013) by Ruth Ozeki. Diarist Nao is spiritually lost. Feeling neither American or Japanese (born in the former, but living in the latter), she visits her grandmother in Sendai. This is a complex, deep, and beautifully told story about finding solace in spirituality. Meanwhile, Ruth, a novelist living on a small island off the coast of British Columbia, finds Nao’s diary washed up on the beach -- possibly from the tsunami that struck Japan in 2011. Ruth has a strong connection to Nao, but is it magic, or is it the power of narrative?

You read:

American Gods (2001) by Neil Gaiman. No one is more in tune with modern fantasy than Neil Gaiman. This is an epic take on the American road trip but with added gods. A convict called Shadow is caught up in a battle between the old gods that the immigrants brought to America, and the new ones people are worshiping. Gaiman treats his subject with utmost seriousness while telling a ripping good yarn.

Now try:

The Shining Girls (2013) by Lauren Beukes causes some debate. Is it science fiction or is it fantasy? Sure it is a time-travel tale, but the mechanism of travel has no basis in science. Gaiman, an Englishman, and Beukes, a South African, provide an alternative perspective on cultural America. A drifter murders the titular girls with magical potential, which somehow allow him to travel through time via a door in a house. Kirby, a potential victim from 1989, recalls encounters with a strange visitor throughout her life. Connecting the clues, she concludes that several murders throughout the century are the work of this same man. She determines to hunt and stop him. As several time periods occur in Beukes beautifully written and carefully crafted novel, it allows comment on the changes in American society.

The People in the Trees (2013) by Hanya Yanagihara. Whereas Gaiman and Beukes use fantasy to comment on culture from a removed stance, Yanagihara looks at cultural impact head on, with the added and very difficult subject of abuse. Fantasy isn’t all about spells and magic rings. In a complex plot, Western scientists visit the mysterious island of U'ivu to research a lost tribe who claim to have eternal life. Yanagihara’s prose has an appropriate dream-like quality as it explores our perceptions through the idea that magic is a part of nature to some cultures.

You read:

The Harry Potter series (1997-2007) by J.K. Rowling. The story of a magician and his friends who grow up learning how to use magic in the world and to fight a series of evil enemies. As with other teen fantasies (such as TV series Buffy the Vampire Slayer), these books are more about growing up and understanding the world than they are about magic and monsters.

Now try:

The Magicians (2009) by Lev Grossman is, from one perspective, Narnia remixed starring Harry Potter at university with swearing and sex. Which sounds great to me! From another, it is about addiction and control. Quentin (Harry) loves the fantasy books Fillory and Further (Chronicles of Narnia). Thinking he is applying to Princeton, he ends up at Brakebills College for Magical Pedagogy (Hogwarts). He learns about magic while making new friends and falling in love, while is former best friend, Julia, who failed to get to Brakebills, learns about magic from the outside world. There are beasts and fights and double crossing and the discovery that Fillory is real. Rollicking good fun with plenty of magic and monsters, but Grossman adds an unexpected depth to the story.

Signal to Noise (2015) by Silvia Moreno-Garcia is a perfect fantasy novel for anyone who was a teenager in the 1980s. I’d imagine it is pretty enjoyable for everyone else too. This time, there is no formal education in magic. Set in Mexico, Signal to Noise charts the growing pains of Meche and her friends Sebastian and Daniela. The make magic from music. Literally. Magic corrupts Meche and her character changes. Moreno-Garcia nails how selfish you can be as a teenager once you get a whiff of power or dominance. In the end, everything falls apart.

Image Credit: Pixabay.

A Year in Reading: Katie Coyle

For the first five months of this year I was too deliriously happy to pay much attention to anyone’s written words, including my own. I was pregnant, due in August. Though I knew when our daughter was born I’d read and write much less for a while, focusing my time and energy on her, I made only halfhearted stabs at parenting literature both practical (Pamela Druckerman’s Bringing Up Bébé) and philosophical (Rachel Cusk’s A Life’s Work). I gave up on other literature almost entirely. Most of what I read those months I read on the August 2015 Babycenter.com birth board, where other mothers with babies expected the same month as mine gathered to share their weird anxieties and basic biological ignorance. I forget now too much of what it felt like to be cheerfully, healthily pregnant with that so loved, so desired child. But I remember the Babycenter posts of other women like scraps of weird poetry recited in old dreams: will Kraft mac and cheese / make my kid dumber? If you live in a haunted house while pregnant / will your baby be the ghost reincarnated? We found out it was a girl and / my husband went outside to vomit.

Our daughter was not born in August. Her heart developed weirdly, wrongly, and she was stillborn in May. For the past six months I’ve been tending not to the baby I’d anticipated, but to the sorrow of having lost her, as tangible and time-consuming a presence as any tiny person. To say I’ve been miserable this year is both overstatement and understatement -- because I have many good days, more good days than bad ones, and yet when the bad ones arrive they can sometimes seem so dark as to be almost unendurable.

To endure them, I read. I read Edith Wharton, detective novels, memoirs by chefs. The Night Circus. Frankenstein. Elena Ferrante, who left me embarrassingly cold. (As if grief were not isolating enough, I am apparently the only literary feminist of my acquaintance who is inexplicably immune to Ferrante Fever). I read the copy of Laurie Colwin’s Happy All the Time that my wonderful agent sent me -- a witty, absorbing book in which no one feels too bad for too long. P.G. Wodehouse, Meg Wolitzer, Nancy Mitford, countless YA novels, cookbooks, chick lit. The Middlesteins. Dept. of Speculation. Rules of Civility. A Visit from the Goon Squad. In every one of these books I looked for, and in nearly all I found, shades of the awful, comforting truth: everyone despairs; nearly everyone survives.

Some books were more explicit about this than others, and these I devoured, though reading them felt sometimes like pressing down hard on a bruise. Matthew Baker’s melancholy and clever middle grade novel, If You Find This, follows a young narrator who confides in a tree in his backyard that he believes contains the soul of his stillborn brother -- I waited anxiously for another character to disabuse him of this notion, but, kindly, no one ever does. Elizabeth McCracken’s story collection Thunderstruck captures the mundane and the surreal of grief, such as “the people who believed that not mentioning sadness was a kind of magic that could stave off the very sadness you didn’t mention -- as though grief were the opposite of Rumpelstiltskin and materialized only at the sound of its own name.” Before this year, such a sentence might not have even registered with me -- but by the time I read it, a few weeks after my daughter’s death, after the initial rally of support gave way to a lot of uncomfortable silence, I heard in it the delicious snap of truth. (I’m still reading, very slowly, McCracken’s memoir of her own stillbirth, An Exact Replica of a Figment of My Imagination, and have never felt so grateful for a book I’m too tender, most days, to open). And for the first time, I waded my way through T.H. White’s The Once and Future King, a more haunting book than I’d expected, in which Merlyn prescribes for Wart the best cure for sadness: “Learn why the world wags and what wags it. That is the only thing which the mind can never exhaust, never alienate, never be tortured by, never fear or distrust, and never dream of regretting. Learning is the thing for you.”

I’d found my way to White through Helen Macdonald’s beautiful H Is for Hawk, a book that’s part hawking manual, part literary biography of T.H. White, and part meditation on grief. Macdonald writes about her experience training a goshawk, one of nature’s most vicious predators, in the wake of her father’s death; she interweaves this narrative with one of White’s own emotional pain and falconry. It’s a strange book -- crisply written, funny, and wrenching, unlike anything I’ve ever read before. But this year, it also happened to be intensely familiar to me. “There is a time in life when you expect the world to be always full of new things,” Macdonald writes. “And then there comes a day when you realize...that life will become a thing made of holes. Absences. Losses.” Like Macdonald, my loss made me feel disconnected from the world I’d once inhabited. I thought of myself as a Grief Monster: a creature too sad and angry to be rightly categorized as human, unable to appreciate simple pleasures, sent into a tailspin at the sight of other mothers’ healthy babies. I could not imagine feeling normal around other people again; I could not imagine wanting to. Macdonald channeled her Grief Monsterhood into the wild, into her hawk, longing somewhat more than wistfully to achieve the bird’s isolation, her self-sufficiency. It doesn’t work that way, Macdonald finds, nor should it: “Hands are for other human hands to hold. They should not be reserved exclusively as perches for hawks.”

Even before I was pregnant with her, when she was nothing more or less than a dream my husband and I shared of a cozy, sunny future, we’d given our first child a code name: Hawkeye. It was partly a nod to the Marvel superhero as written by Matt Fraction, mostly an homage to my husband’s love for M*A*S*H. We called her Hawk for short. We figured when she was born we’d give her a “real” name; we had one chosen and ready, but through what we then considered silly superstition, we never said it out loud much. When she died, it became impossible to think of her as anything but Hawk -- impossible to separate the real, sweet, three-pound baby we’d held for a few quiet hours early on a morning in May from her infinite and unrealized potential. We’d imagined too many happy possibilities for the girl with the other name. For ourselves. So Hawkeye was the name we shared with the diplomatically unperturbed nurse who asked; Hawkeye was the name we wrote on the death certificate. Hawk is the name we call her still and always. It’s a word that can’t help but mean more to me now. Bird, daughter. Love, loss. Despair. Survival. Losing Hawk helped me understand that I remain stubbornly, sublimely human even when I’m hurting. Thanks to H Is for Hawk, her name reminds me that I want to be. Macdonald writes of dreams she’d had after her father died, anxious dreams in which a hawk glided out of her sight:

I had thought for a long while that I was the hawk -- one of those sulky goshawks able to vanish into another world, sitting high in the winter trees. But I was not the hawk, no matter how much I pared myself away, no matter how many times I lost myself in blood and leaves and fields. I was the figure standing underneath the tree at nightfall, collar upturned against the damp, waiting patiently for the hawk to return.

More from A Year in Reading 2015

Don't miss: A Year in Reading 2014, 2013, 2012, 2011, 2010, 2009, 2008, 2007, 2006, 2005

The good stuff: The Millions' Notable articles

The motherlode: The Millions' Books and Reviews

Like what you see? Learn about 5 insanely easy ways to Support The Millions, and follow The Millions on Twitter, Facebook, Tumblr.

Choosing Not to Flee: On Helen Macdonald’s ‘H is for Hawk’

Knowing how to make yourself disappear does not serve you well in life, writes Helen Macdonald, unless you are attempting to train a hawk. When there is a goshawk on her arm, a huge bird of prey who has no experience with the human world and who is staring at her in absolute terror, Macdonald can make herself invisible. Holding a chunk of raw steak in her hand, her goal is to get the hawk to forget about her, to forget the terror, and eat. “But the space between the fear and the food is a vast, vast gulf,” she writes, “and you have to cross it together.” To do that, you must disappear: you empty your mind, you remain still, you “think of exactly nothing at all.” You gradually expand your invisibility to cover everything in the room except the food, which you squeeze slightly. When the hawk begins to eat, you may, very slowly, reappear.

A professor of mine introduced me to that idea a couple of years ago; for him, the process of crossing a “vast gulf” while negotiating your own visibility was akin to the process of translation (a word which means, in fact, “to carry across”). As it appears in Macdonald’s new book, H is for Hawk, the scene serves as a metaphor of a different, though related, kind: as a journey from death into life, from absence into presence. It is no accident that this journey is mediated by a bird of prey. In many of the world’s mythic traditions, hawks are cast as the messengers of the gods and the companions of the soul on its voyage to the afterlife. In ancient Egyptian mythology, the ba (the immortal part of the soul) departs the body in the shape of a hawk.

The goshawk, in Macdonald’s scene of invisibility, represents a bridge between two worlds: fear and food, death and life. Like many books about hawks, H is for Hawk begins on the side of death. Macdonald’s father passes away suddenly in the book’s first pages, and the author finds herself before a vast gulf of grief. Sorrow is not a rational problem and cannot be solved by rational means; as a poet and falconer, Macdonald seeks out a poetic, avian remedy to her pain. Soon after her father’s death, she starts dreaming of hawks “all the time.” She orders a goshawk from Northern Ireland, and when it arrives, she sets it on her arm and turns invisible.

Read symbolically, Macdonald’s act of disappearance becomes much more than an effective training technique; it becomes a deliberate act of surrender to the unconscious, an appeal to a shadow guide. Erasing yourself for the sake of a hawk is one way of learning that you must disappear before you can be present in your own life.

H is for Hawk is not a mystical book, but it is one of those rare works of non-fiction that stand up to a metaphorical reading. The echoes of myth in Macdonald’s writing, however subtle and unobtrusive, lend her book an emotional weight usually reserved only for literature, and a grace only for poetry. But this is one of the book’s great achievements: to belong to several genres at once, and to succeed at all of them. The narrative includes elements from memoir, biography, and natural history, with some chapters exploring the human history of Macdonald’s English landscape and others turning inward, toward Macdonald herself and her ghostly counterpart, the writer T.H. White. Translating between them, guiding the reader as it once guided lost souls, there is always the goshawk.

Of all birds of prey, the goshawk is the most difficult to train. Described by hawking manuals as “jumpy, fractious, unsociable,” goshawks are temperamental, prone to fits of “passing madness” in which they perch on a high tree branch and refuse to come down, resolutely ignoring the hopeless humans who wait for them below. They have never been domesticated and never even truly tamed. More than any other bird, they seem to embody the Romantic sublime, terrifying and magnificent at once: Macdonald describes her own hawk as “a dinosaur pulled from the Forest of Dean” and “something bright and distant, like gold falling through water.”

Though a highly accomplished falconer, Macdonald writes that, before her father’s death, she had never wanted to train a goshawk. She preferred peregrines, which her books assured her were “the finest bird[s] on earth.” “It took me years,” she says, “to work out that this glorification of falcons was partly down to who got to fly them.” The falcon is a rich man’s bird: flying a peregrine requires huge amounts of space, a luxury traditionally only available to aristocrats with large country estates. A goshawk, by contrast, can be flown anywhere, and were therefore popular among those without wealth or connections. These solitary trainers, known as austringers, were disdained by the aristocratic falconer community, cursed for “hat[ing] company and go[ing] alone at their sport.” The goshawk is the bird of the temporary exile, and Macdonald was not the first to seek it out in lieu of human company. Indeed, no sooner has she decided to man a goshawk than her eyes start avoiding a particular book in her study, “second shelf down. Red cloth cover. Silver-lettered spine.”

The book is T.H. White’s The Goshawk, a record of the author’s attempt to train, as he put it, “a person who was not human, but a bird.” Written in 1936, though not published until 1951, the book was condemned as a falconer’s checklist of what not to do. White had never trained a hawk before; he was inexperienced, he was using manuals centuries out of date, and he unintentionally caused his hawk, a tiercel (male) named Gos, a great deal of suffering. Macdonald had read The Goshawk as a hawk-obsessed child and found it infuriating. And yet, as soon as she has arranged for a Gos of her own, she unconsciously reaches out to this author who, like herself, wanted to disappear.

The brilliant but “unfashionable” writer best known for his Arthurian saga The Once and Future King, Terence Hanbury White was, in Macdonald’s words, “one of the loneliest men alive.” Homosexual and self-loathing, with a sadistic streak, White spent much of his energy trying to flee from humanity. His two great refuges were writing and the outdoors. The Goshawk was his first book as a full-time author; despite its failings as a work of falconry, it is a marvelous piece of literature. Macdonald reads it several times in the months she spends with her own hawk, and observes that “every time it seemed a different book; sometimes a caustically funny romance, sometimes the journal of a man laughing at failure, sometimes a heartbreaking tract of another man’s despair.”

Though H is for Hawk is not intended to be a biography of White, Macdonald explains, “I have to write about him because he was there.” Some of her reasons for sequestering herself with a goshawk, she realizes, are not her own but White’s; and though the personalities and experiences of the two writers are quite different, there is still a strange kinship between them. “Like White I wanted to cut loose from the world,” Macdonald writes, “and I shared, too, his desire to escape to the wild, a desire that can rip away all human softness and leave you stranded in a world of savage, courteous despair.” Here, too, the goshawk is the messenger between the living and the dead: across the gulf of time, Macdonald finds in White a companion, a point of reference, an object of study, and her own foil.

White lived in constant fear. He feared the cruelty of his homophobic, militaristic society, and, especially, the cruelty he felt within himself. He knew that enjoyed inflicting pain and he hated himself for it, and so always took great care to be gentle. (Of Sir Lancelot, his double, White wrote: “He felt in his heart cruelty and cowardice, the things which made him brave and kind.”) White wanted desperately to be good, but believed goodness was only possible away from his fellow man. Spending time with Gos, a “person who was not human,” was the only way he could tolerate his own humanity. Training Gos offered him a chance to confront his own darkness and not merely repress it; one of the many ways to read The Goshawk, Macdonald says, is as a war, where, through Gos, White “battled the dictator in himself.” White ultimately lost that battle; perhaps he failed to recognize Gos as his guide, and instead mistook him for his enemy, albeit a much-loved one.

Macdonald, though she, too, yearns to leave her weaknesses behind, never sees her own hawk as an adversary. She understands that her hawk is not only the individual she has named Mabel, but a tangle of many centuries’ worth of human associations. “So much of what she means is made of people,” Macdonald muses. Shortly afterward, she discovers that Mabel likes to play; she likes the sound of crinkled paper, and she shakes in bird-laughter when Macdonald calls to her through a rolled magazine telescope. The revelation is a delight, yet it fills Macdonald with an “obscure shame.” “I had a fixed idea of what a goshawk was,” she writes, “...and it was not big enough to hold what goshawks are. No one had ever told me goshawks played. It was not in the books. I had not imagined it was possible.”

But writers know better than most that books cannot always be trusted. Books urge us to flee to the wild when our hearts are broken; books, like John Muir’s, assure us that “Earth hath no sorrows that earth cannot heal.” Macdonald argues that our ideas of nature, like our ideas of goshawks, are too small, having more to do with ourselves than with the world around us. “I’d fled to become a hawk,” she writes, “but in my misery all I had done was turn the hawk into a mirror of me.” Here again, that ability to disappear, which Macdonald says serves her so badly elsewhere in life, proves crucial. When she makes herself invisible -- suspending her ego, suspending the knowledge of books -- she begins to understand what, in fact, she has been trying to do.