Mentioned in:

Most Anticipated: The Great Winter 2025 Preview

It's cold, it's grey, its bleak—but winter, at the very least, brings with it a glut of anticipation-inducing books. Here you’ll find nearly 100 titles that we’re excited to cozy up with this season. Some we’ve already read in galley form; others we’re simply eager to devour based on their authors, subjects, or blurbs. We'd love for you to find your next great read among them.

The Millions will be taking a hiatus for the next few months, but we hope to see you soon.

—Sophia Stewart, editor

January

The Legend of Kumai by Shirato Sanpei, tr. Richard Rubinger (Drawn & Quarterly)

The epic 10-volume series, a touchstone of longform storytelling in manga now published in English for the first time, follows outsider Kamui in 17th-century Japan as he fights his way up from peasantry to the prized role of ninja. —Michael J. Seidlinger

The Life of Herod the Great by Zora Neale Hurston (Amistad)

In the years before her death in 1960, Hurston was at work on what she envisioned as a continuation of her 1939 novel, Moses, Man of the Mountain. Incomplete, nearly lost to fire, and now published for the first time alongside scholarship from editor Deborah G. Plant, Hurston’s final manuscript reimagines Herod, villain of the New Testament Gospel accounts, as a magnanimous and beloved leader of First Century Judea. —Jonathan Frey

Mood Machine by Liz Pelly (Atria)

When you eagerly posted your Spotify Wrapped last year, did you notice how much of what you listened to tended to sound... the same? Have you seen all those links to Bandcamp pages your musician friends keep desperately posting in the hopes that maybe, just maybe, you might give them money for their art? If so, this book is for you. —John H. Maher

My Country, Africa by Andrée Blouin (Verso)

African revolutionary Blouin recounts a radical life steeped in activism in this vital autobiography, from her beginnings in a colonial orphanage to her essential role in the continent's midcentury struggles for decolonization. —Sophia M. Stewart

The First and Last King of Haiti by Marlene L. Daut (Knopf)

Donald Trump repeatedly directs extraordinary animus towards Haiti and Haitians. This biography of Henry Christophe—the man who played a pivotal role in the Haitian Revolution—might help Americans understand why. —Claire Kirch

The Bewitched Bourgeois by Dino Buzzati, tr. Lawrence Venuti (NYRB)

This is the second story collection, and fifth book, by the absurdist-leaning midcentury Italian writer—whose primary preoccupation was war novels that blend the brutal with the fantastical—to get the NYRB treatment. May it not be the last. —JHM

Y2K by Colette Shade (Dey Street)

The recent Y2K revival mostly makes me feel old, but Shade's essay collection deftly illuminates how we got here, connecting the era's social and political upheavals to today. —SMS

Darkmotherland by Samrat Upadhyay (Penguin)

In a vast dystopian reimagining of Nepal, Upadhyay braids narratives of resistance (political, personal) and identity (individual, societal) against a backdrop of natural disaster and state violence. The first book in nearly a decade from the Whiting Award–winning author of Arresting God in Kathmandu, this is Upadhyay’s most ambitious yet. —JF

Metamorphosis by Ross Jeffery (Truborn)

From the author of I Died Too, But They Haven’t Buried Me Yet, a woman leads a double life as she loses her grip on reality by choice, wearing a mask that reflects her inner demons, as she descends into a hell designed to reveal the innermost depths of her grief-stricken psyche. —MJS

The Containment by Michelle Adams (FSG)

Legal scholar Adams charts the failure of desegregation in the American North through the story of the struggle to integrate suburban schools in Detroit, which remained almost completely segregated nearly two decades after Brown v. Board. —SMS

Death of the Author by Nnedi Okorafor (Morrow)

African Futurist Okorafor’s book-within-a-book offers interchangeable cover images, one for the story of a disabled, Black visionary in a near-present day and the other for the lead character’s speculative posthuman novel, Rusted Robots. Okorafor deftly keeps the alternating chapters and timelines in conversation with one another. —Nathalie op de Beeck

Open Socrates by Agnes Callard (Norton)

Practically everything Agnes Callard says or writes ushers in a capital-D Discourse. (Remember that profile?) If she can do the same with a study of the philosophical world’s original gadfly, culture will be better off for it. —JHM

Aflame by Pico Iyer (Riverhead)

Presumably he finds time to eat and sleep in there somewhere, but it certainly appears as if Iyer does nothing but travel and write. His latest, following 2023’s The Half Known Life, makes a case for the sublimity, and necessity, of silent reflection. —JHM

The In-Between Bookstore by Edward Underhill (Avon)

A local bookstore becomes a literal portal to the past for a trans man who returns to his hometown in search of a fresh start in Underhill's tender debut. —SMS

Good Girl by Aria Aber (Hogarth)

Aber, an accomplished poet, turns to prose with a debut novel set in the electric excess of Berlin’s bohemian nightlife scene, where a young German-born Afghan woman finds herself enthralled by an expat American novelist as her country—and, soon, her community—is enflamed by xenophobia. —JHM

The Orange Eats Creeps by Grace Krilanovich (Two Dollar Radio)

Krilanovich’s 2010 cult classic, about a runaway teen with drug-fueled ESP who searches for her missing sister across surreal highways while being chased by a killer named Dactyl, gets a much-deserved reissue. —MJS

Mona Acts Out by Mischa Berlinski (Liveright)

In the latest novel from the National Book Award finalist, a 50-something actress reevaluates her life and career when #MeToo allegations roil the off-off-Broadway Shakespearean company that has cast her in the role of Cleopatra. —SMS

Something Rotten by Andrew Lipstein (FSG)

A burnt-out couple leave New York City for what they hope will be a blissful summer in Denmark when their vacation derails after a close friend is diagnosed with a rare illness and their marriage is tested by toxic influences. —MJS

The Sun Won't Come Out Tomorrow by Kristen Martin (Bold Type)

Martin's debut is a cultural history of orphanhood in America, from the 1800s to today, interweaving personal narrative and archival research to upend the traditional "orphan narrative," from Oliver Twist to Annie. —SMS

We Do Not Part by Han Kang, tr. E. Yaewon and Paige Aniyah Morris (Hogarth)

Kang’s Nobel win last year surprised many, but the consistency of her talent certainly shouldn't now. The latest from the author of The Vegetarian—the haunting tale of a Korean woman who sets off to save her injured friend’s pet at her home in Jeju Island during a deadly snowstorm—will likely once again confront the horrors of history with clear eyes and clarion prose. —JHM

We Are Dreams in the Eternal Machine by Deni Ellis Béchard (Milkweed)

As the conversation around emerging technology skews increasingly to apocalyptic and utopian extremes, Béchard’s latest novel adopts the heterodox-to-everyone approach of embracing complexity. Here, a cadre of characters is isolated by a rogue but benevolent AI into controlled environments engineered to achieve their individual flourishing. The AI may have taken over, but it only wants to best for us. —JF

The Harder I Fight the More I Love You by Neko Case (Grand Central)

Singer-songwriter Case, a country- and folk-inflected indie rocker and sometime vocalist for the New Pornographers, takes her memoir’s title from her 2013 solo album. Followers of PNW music scene chronicles like Kathleen Hanna’s Rebel Girl and drummer Steve Moriarty’s Mia Zapata and the Gits will consider Case’s backstory a must-read. —NodB

The Loves of My Life by Edmund White (Bloomsbury)

The 85-year-old White recounts six decades of love and sex in this candid and erotic memoir, crafting a landmark work of queer history in the process. Seminal indeed. —SMS

Blob by Maggie Su (Harper)

In Su’s hilarious debut, Vi Liu is a college dropout working a job she hates, nothing really working out in her life, when she stumbles across a sentient blob that she begins to transform as her ideal, perfect man that just might resemble actor Ryan Gosling. —MJS

Sinkhole and Other Inexplicable Voids by Leyna Krow (Penguin)

Krow’s debut novel, Fire Season, traced the combustible destinies of three Northwest tricksters in the aftermath of an 1889 wildfire. In her second collection of short fiction, Krow amplifies surreal elements as she tells stories of ordinary lives. Her characters grapple with deadly viruses, climate change, and disasters of the Anthropocene’s wilderness. —NodB

Black in Blues by Imani Perry (Ecco)

The National Book Award winner—and one of today's most important thinkers—returns with a masterful meditation on the color blue and its role in Black history and culture. —SMS

Too Soon by Betty Shamieh (Avid)

The timely debut novel by Shamieh, a playwright, follows three generations of Palestinian American women as they navigate war, migration, motherhood, and creative ambition. —SMS

How to Talk About Love by Plato, tr. Armand D'Angour (Princeton UP)

With modern romance on its last legs, D'Angour revisits Plato's Symposium, mining the philosopher's masterwork for timeless, indispensable insights into love, sex, and attraction. —SMS

At Dark, I Become Loathsome by Eric LaRocca (Blackstone)

After Ashley Lutin’s wife dies, he takes the grieving process in a peculiar way, posting online, “If you're reading this, you've likely thought that the world would be a better place without you,” and proceeds to offer a strange ritual for those that respond to the line, equally grieving and lost, in need of transcendence. —MJS

February

No One Knows by Osamu Dazai, tr. Ralph McCarthy (New Directions)

A selection of stories translated in English for the first time, from across Dazai’s career, demonstrates his penchant for exploring conformity and society’s often impossible expectations of its members. —MJS

Mutual Interest by Olivia Wolfgang-Smith (Bloomsbury)

This queer love story set in post–Gilded Age New York, from the author of Glassworks (and one of my favorite Millions essays to date), explores on sex, power, and capitalism through the lives of three queer misfits. —SMS

Pure, Innocent Fun by Ira Madison III (Random House)

This podcaster and pop culture critic spoke to indie booksellers at a fall trade show I attended, regaling us with key cultural moments in the 1990s that shaped his youth in Milwaukee and being Black and gay. If the book is as clever and witty as Madison is, it's going to be a winner. —CK

Gliff by Ali Smith (Pantheon)

The Scottish author has been on the scene since 1997 but is best known today for a seasonal quartet from the late twenty-teens that began in 2016 with Autumn and ended in 2020 with Summer. Here, she takes the genre turn, setting two children and a horse loose in an authoritarian near future. —JHM

Land of Mirrors by Maria Medem, tr. Aleshia Jensen and Daniela Ortiz (D&Q)

This hypnotic graphic novel from one of Spain's most celebrated illustrators follows Antonia, the sole inhabitant of a deserted town, on a color-drenched quest to preserve the dying flower that gives her purpose. —SMS

Bibliophobia by Sarah Chihaya (Random House)

As odes to the "lifesaving power of books" proliferate amid growing literary censorship, Chihaya—a brilliant critic and writer—complicates this platitude in her revelatory memoir about living through books and the power of reading to, in the words of blurber Namwali Serpell, "wreck and redeem our lives." —SMS

Reading the Waves by Lidia Yuknavitch (Riverhead)

Yuknavitch continues the personal story she began in her 2011 memoir, The Chronology of Water. More than a decade after that book, and nearly undone by a history of trauma and the death of her daughter, Yuknavitch revisits the solace she finds in swimming (she was once an Olympic hopeful) and in her literary community. —NodB

The Dissenters by Youssef Rakha (Graywolf)

A son reevaluates the life of his Egyptian mother after her death in Rakha's novel. Recounting her sprawling life story—from her youth in 1960s Cairo to her experience of the 2011 Tahrir Square protests—a vivid portrait of faith, feminism, and contemporary Egypt emerges. —SMS

Tetra Nova by Sophia Terazawa (Deep Vellum)

Deep Vellum has a particularly keen eye for fiction in translation that borders on the unclassifiable. This debut from a poet the press has published twice, billed as the story of “an obscure Roman goddess who re-imagines herself as an assassin coming to terms with an emerging performance artist identity in the late-20th century,” seems right up that alley. —JHM

David Lynch's American Dreamscape by Mike Miley (Bloomsbury)

Miley puts David Lynch's films in conversation with literature and music, forging thrilling and unexpected connections—between Eraserhead and "The Yellow Wallpaper," Inland Empire and "mixtape aesthetics," Lynch and the work of Cormac McCarthy. Lynch devotees should run, not walk. —SMS

There's No Turning Back by Alba de Céspedes, tr. Ann Goldstein (Washington Square)

Goldstein is an indomitable translator. Without her, how would you read Ferrante? Here, she takes her pen to a work by the great Cuban-Italian writer de Céspedes, banned in the fascist Italy of the 1930s, that follows a group of female literature students living together in a Roman boarding house. —JHM

Beta Vulgaris by Margie Sarsfield (Norton)

Named for the humble beet plant and meaning, in a rough translation from the Latin, "vulgar second," Sarsfield’s surreal debut finds a seasonal harvest worker watching her boyfriend and other colleagues vanish amid “the menacing but enticing siren song of the beets.” —JHM

People From Oetimu by Felix Nesi, tr. Lara Norgaard (Archipelago)

The center of Nesi’s wide-ranging debut novel is a police station on the border between East and West Timor, where a group of men have gathered to watch the final of the 1998 World Cup while a political insurgency stirs without. Nesi, in English translation here for the first time, circles this moment broadly, reaching back to the various colonialist projects that have shaped Timor and the lives of his characters. —JF

Brother Brontë by Fernando A. Flores (MCD)

This surreal tale, set in a 2038 dystopian Texas is a celebration of resistance to authoritarianism, a mash-up of Olivia Butler, Ray Bradbury, and John Steinbeck. —CK

Alligator Tears by Edgar Gomez (Crown)

The High-Risk Homosexual author returns with a comic memoir-in-essays about fighting for survival in the Sunshine State, exploring his struggle with poverty through the lens of his queer, Latinx identity. —SMS

Theory & Practice by Michelle De Kretser (Catapult)

This lightly autofictional novel—De Krester's best yet, and one of my favorite books of this year—centers on a grad student's intellectual awakening, messy romantic entanglements, and fraught relationship with her mother as she minds the gap between studying feminist theory and living a feminist life. —SMS

The Lamb by Lucy Rose (Harper)

Rose’s cautionary and caustic folk tale is about a mother and daughter who live alone in the forest, quiet and tranquil except for the visitors the mother brings home, whom she calls “strays,” wining and dining them until they feast upon the bodies. —MJS

Disposable by Sarah Jones (Avid)

Jones, a senior writer for New York magazine, gives a voice to America's most vulnerable citizens, who were deeply and disproportionately harmed by the pandemic—a catastrophe that exposed the nation's disregard, if not outright contempt, for its underclass. —SMS

No Fault by Haley Mlotek (Viking)

Written in the aftermath of the author's divorce from the man she had been with for 12 years, this "Memoir of Romance and Divorce," per its subtitle, is a wise and distinctly modern accounting of the end of a marriage, and what it means on a personal, social, and literary level. —SMS

Enemy Feminisms by Sophie Lewis (Haymarket)

Lewis, one of the most interesting and provocative scholars working today, looks at certain malignant strains of feminism that have done more harm than good in her latest book. In the process, she probes the complexities of gender equality and offers an alternative vision of a feminist future. —SMS

Lion by Sonya Walger (NYRB)

Walger—an successful actor perhaps best known for her turn as Penny Widmore on Lost—debuts with a remarkably deft autobiographical novel (published by NYRB no less!) about her relationship with her complicated, charismatic Argentinian father. —SMS

The Voices of Adriana by Elvira Navarro, tr. Christina MacSweeney (Two Lines)

A Spanish writer and philosophy scholar grieves her mother and cares for her sick father in Navarro's innovative, metafictional novel. —SMS

Autotheories ed. Alex Brostoff and Vilashini Cooppan (MIT)

Theory wonks will love this rigorous and surprisingly playful survey of the genre of autotheory—which straddles autobiography and critical theory—with contributions from Judith Butler, Jamieson Webster, and more.

Fagin the Thief by Allison Epstein (Doubleday)

I enjoy retellings of classic novels by writers who turn the spotlight on interesting minor characters. This is an excursion into the world of Charles Dickens, told from the perspective iconic thief from Oliver Twist. —CK

Crush by Ada Calhoun (Viking)

Calhoun—the masterful memoirist behind the excellent Also A Poet—makes her first foray into fiction with a debut novel about marriage, sex, heartbreak, all-consuming desire. —SMS

Show Don't Tell by Curtis Sittenfeld (Random House)

Sittenfeld's observations in her writing are always clever, and this second collection of short fiction includes a tale about the main character in Prep, who visits her boarding school decades later for an alumni reunion. —CK

Right-Wing Woman by Andrea Dworkin (Picador)

One in a trio of Dworkin titles being reissued by Picador, this 1983 meditation on women and American conservatism strikes a troublingly resonant chord in the shadow of the recent election, which saw 45% of women vote for Trump. —SMS

The Talent by Daniel D'Addario (Scout)

If your favorite season is awards, the debut novel from D'Addario, chief correspondent at Variety, weaves an awards-season yarn centering on five stars competing for the Best Actress statue at the Oscars. If you know who Paloma Diamond is, you'll love this. —SMS

Death Takes Me by Cristina Rivera Garza, tr. Sarah Booker and Robin Myers (Hogarth)

The Pulitzer winner’s latest is about an eponymously named professor who discovers the body of a mutilated man with a bizarre poem left with the body, becoming entwined in the subsequent investigation as more bodies are found. —MJS

The Strange Case of Jane O. by Karen Thompson Walker (Random House)

Jane goes missing after a sudden a debilitating and dreadful wave of symptoms that include hallucinations, amnesia, and premonitions, calling into question the foundations of her life and reality, motherhood and buried trauma. —MJS

Song So Wild and Blue by Paul Lisicky (HarperOne)

If it weren’t Joni Mitchell’s world with all of us just living in it, one might be tempted to say the octagenarian master songstress is having a moment: this memoir of falling for the blue beauty of Mitchell’s work follows two other inventive books about her life and legacy: Ann Powers's Traveling and Henry Alford's I Dream of Joni. —JHM

Mornings Without Mii by Mayumi Inaba, tr. Ginny Tapley (FSG)

A woman writer meditates on solitude, art, and independence alongside her beloved cat in Inaba's modern classic—a book so squarely up my alley I'm somehow embarrassed. —SMS

True Failure by Alex Higley (Coffee House)

When Ben loses his job, he decides to pretend to go to work while instead auditioning for Big Shot, a popular reality TV show that he believes might be a launchpad for his future successes. —MJS

March

Woodworking by Emily St. James (Crooked Reads)

Those of us who have been reading St. James since the A.V. Club days may be surprised to see this marvelous critic's first novel—in this case, about a trans high school teacher befriending one of her students, the only fellow trans woman she’s ever met—but all the more excited for it. —JHM

Optional Practical Training by Shubha Sunder (Graywolf)

Told as a series of conversations, Sunder’s debut novel follows its recently graduated Indian protagonist in 2006 Cambridge, Mass., as she sees out her student visa teaching in a private high school and contriving to find her way between worlds that cannot seem to comprehend her. Quietly subversive, this is an immigration narrative to undermine the various reductionist immigration narratives of our moment. —JF

Love, Queenie by Mayukh Sen (Norton)

Merle Oberon, one of Hollywood's first South Asian movie stars, gets her due in this engrossing biography, which masterfully explores Oberon's painful upbringing, complicated racial identity, and much more. —SMS

The Age of Choice by Sophia Rosenfeld (Princeton UP)

At a time when we are awash with options—indeed, drowning in them—Rosenfeld's analysis of how our modingn idea of "freedom" became bound up in the idea of personal choice feels especially timely, touching on everything from politics to romance. —SMS

Sucker Punch by Scaachi Koul (St. Martin's)

One of the internet's funniest writers follows up One Day We'll All Be Dead and None of This Will Matter with a sharp and candid collection of essays that sees her life go into a tailspin during the pandemic, forcing her to reevaluate her beliefs about love, marriage, and what's really worth fighting for. —SMS

The Mysterious Disappearance of the Marquise of Loria by José Donoso, tr. Megan McDowell (New Directions)

The ever-excellent McDowell translates yet another work by the influential Chilean author for New Directions, proving once again that Donoso had a knack for titles: this one follows up 2024’s behemoth The Obscene Bird of Night. —JHM

Remember This by Anthony Giardina (FSG)

On its face, it’s another book about a writer living in Brooklyn. A layer deeper, it’s a book about fathers and daughters, occupations and vocations, ethos and pathos, failure and success. —JHM

Ultramarine by Mariette Navarro (Deep Vellum)

In this metaphysical and lyrical tale, a captain known for sticking to protocol begins losing control not only of her crew and ship but also her own mind. —MJS

We Tell Ourselves Stories by Alissa Wilkinson (Liveright)

Amid a spate of new books about Joan Didion published since her death in 2021, this entry by Wilkinson (one of my favorite critics working today) stands out for its approach, which centers Hollywood—and its meaning-making apparatus—as an essential key to understanding Didion's life and work. —SMS

Seven Social Movements that Changed America by Linda Gordon (Norton)

This book—by a truly renowned historian—about the power that ordinary citizens can wield when they organize to make their community a better place for all could not come at a better time. —CK

Mothers and Other Fictional Characters by Nicole Graev Lipson (Chronicle Prism)

Lipson reconsiders the narratives of womanhood that constrain our lives and imaginations, mining the canon for alternative visions of desire, motherhood, and more—from Kate Chopin and Gwendolyn Brooks to Philip Roth and Shakespeare—to forge a new story for her life. —SMS

Goddess Complex by Sanjena Sathian (Penguin)

Doppelgängers have been done to death, but Sathian's examination of Millennial womanhood—part biting satire, part twisty thriller—breathes new life into the trope while probing the modern realities of procreation, pregnancy, and parenting. —SMS

Stag Dance by Torrey Peters (Random House)

The author of Detransition, Baby offers four tales for the price of one: a novel and three stories that promise to put gender in the crosshairs with as sharp a style and swagger as Peters’ beloved latest. The novel even has crossdressing lumberjacks. —JHM

On Breathing by Jamieson Webster (Catapult)

Webster, a practicing psychoanalyst and a brilliant writer to boot, explores that most basic human function—breathing—to address questions of care and interdependence in an age of catastrophe. —SMS

Unusual Fragments: Japanese Stories (Two Lines)

The stories of Unusual Fragments, including work by Yoshida Tomoko, Nobuko Takai, and other seldom translated writers from the same ranks as Abe and Dazai, comb through themes like alienation and loneliness, from a storm chaser entering the eye of a storm to a medical student observing a body as it is contorted into increasingly violent positions. —MJS

The Antidote by Karen Russell (Knopf)

Russell has quipped that this Dust Bowl story of uncanny happenings in Nebraska is the “drylandia” to her 2011 Florida novel, Swamplandia! In this suspenseful account, a woman working as a so-called prairie witch serves as a storage vault for her townspeople’s most troubled memories of migration and Indigenous genocide. With a murderer on the loose, a corrupt sheriff handling the investigation, and a Black New Deal photographer passing through to document Americana, the witch loses her memory and supernatural events parallel the area’s lethal dust storms. —NodB

On the Clock by Claire Baglin, tr. Jordan Stump (New Directions)

Baglin's bildungsroman, translated from the French, probes the indignities of poverty and service work from the vantage point of its 20-year-old narrator, who works at a fast-food joint and recalls memories of her working-class upbringing. —SMS

Motherdom by Alex Bollen (Verso)

Parenting is difficult enough without dealing with myths of what it means to be a good mother. I who often felt like a failure as a mother appreciate Bollen's focus on a more realistic approach to parenting. —CK

The Magic Books by Anne Lawrence-Mathers (Yale UP)

For that friend who wants to concoct the alchemical elixir of life, or the person who cannot quit Susanna Clark’s Jonathan Strange and Mr. Norrell, Lawrence-Mathers collects 20 illuminated medieval manuscripts devoted to magical enterprise. Her compendium includes European volumes on astronomy, magical training, and the imagined intersection between science and the supernatural. —NodB

Theft by Abdulrazak Gurnah (Riverhead)

The first novel by the Tanzanian-British Nobel laureate since his surprise win in 2021 is a story of class, seismic cultural change, and three young people in a small Tanzania town, caught up in both as their lives dramatically intertwine. —JHM

Twelve Stories by American Women, ed. Arielle Zibrak (Penguin Classics)

Zibrak, author of a delicious volume on guilty pleasures (and a great essay here at The Millions), curates a dozen short stories by women writers who have long been left out of American literary canon—most of them women of color—from Frances Ellen Watkins Harper to Zitkala-Ša. —SMS

I'll Love You Forever by Giaae Kwon (Holt)

K-pop’s sky-high place in the fandom landscape made a serious critical assessment inevitable. This one blends cultural criticism with memoir, using major artists and their careers as a lens through which to view the contemporary Korean sociocultural landscape writ large. —JHM

The Buffalo Hunter Hunter by Stephen Graham Jones (Saga)

Jones, the acclaimed author of The Only Good Indians and the Indian Lake Trilogy, offers a unique tale of historical horror, a revenge tale about a vampire descending upon the Blackfeet reservation and the manifold of carnage in their midst. —MJS

True Mistakes by Lena Moses-Schmitt (University of Arkansas Press)

Full disclosure: Lena is my friend. But part of why I wanted to be her friend in the first place is because she is a brilliant poet. Selected by Patricia Smith as a finalist for the Miller Williams Poetry Prize, and blurbed by the great Heather Christle and Elisa Gabbert, this debut collection seeks to turn "mistakes" into sites of possibility. —SMS

Perfection by Vicenzo Latronico, tr. Sophie Hughes (NYRB)

Anna and Tom are expats living in Berlin enjoying their freedom as digital nomads, cultivating their passion for capturing perfect images, but after both friends and time itself moves on, their own pocket of creative freedom turns boredom, their life trajectories cast in doubt. —MJS

Guatemalan Rhapsody by Jared Lemus (Ecco)

Jemus's debut story collection paint a composite portrait of the people who call Guatemala home—and those who have left it behind—with a cast of characters that includes a medicine man, a custodian at an underfunded college, wannabe tattoo artists, four orphaned brothers, and many more.

Pacific Circuit by Alexis Madrigal (MCD)

The Oakland, Calif.–based contributing writer for the Atlantic digs deep into the recent history of a city long under-appreciated and under-served that has undergone head-turning changes throughout the rise of Silicon Valley. —JHM

Barbara by Joni Murphy (Astra)

Described as "Oppenheimer by way of Lucia Berlin," Murphy's character study follows the titular starlet as she navigates the twinned convulsions of Hollywood and history in the Atomic Age.

Sister Sinner by Claire Hoffman (FSG)

This biography of the fascinating Aimee Semple McPherson, America's most famous evangelist, takes religion, fame, and power as its subjects alongside McPherson, whose life was suffused with mystery and scandal. —SMS

Trauma Plot by Jamie Hood (Pantheon)

In this bold and layered memoir, Hood confronts three decades of sexual violence and searches for truth among the wreckage. Kate Zambreno calls Trauma Plot the work of "an American Annie Ernaux." —SMS

Hey You Assholes by Kyle Seibel (Clash)

Seibel’s debut story collection ranges widely from the down-and-out to the downright bizarre as he examines with heart and empathy the strife and struggle of his characters. —MJS

James Baldwin by Magdalena J. Zaborowska (Yale UP)

Zaborowska examines Baldwin's unpublished papers and his material legacy (e.g. his home in France) to probe about the great writer's life and work, as well as the emergence of the "Black queer humanism" that Baldwin espoused. —CK

Stop Me If You've Heard This One by Kristen Arnett (Riverhead)

Arnett is always brilliant and this novel about the relationship between Cherry, a professional clown, and her magician mentor, "Margot the Magnificent," provides a fascinating glimpse of the unconventional lives of performance artists. —CK

Paradise Logic by Sophie Kemp (S&S)

The deal announcement describes the ever-punchy writer’s debut novel with an infinitely appealing appellation: “debauched picaresque.” If that’s not enough to draw you in, the truly unhinged cover should be. —JHM

[millions_email]

A Year in Reading: 2024

Welcome to the 20th (!) installment of The Millions' annual Year in Reading series, which gathers together some of today's most exciting writers and thinkers to share the books that shaped their year. YIR is not a collection of yearend best-of lists; think of it, perhaps, as an assemblage of annotated bibliographies. We've invited contributors to reflect on the books they read this year—an intentionally vague prompt—and encouraged them to approach the assignment however they choose.

In writing about our reading lives, as YIR contributors are asked to do, we inevitably write about our personal lives, our inner lives. This year, a number of contributors read their way through profound grief and serious illness, through new parenthood and cross-country moves. Some found escape in frothy romances, mooring in works of theology, comfort in ancient epic poetry. More than one turned to the wisdom of Ursula K. Le Guin. Many describe a book finding them just when they needed it.

Interpretations of the assignment were wonderfully varied. One contributor, a music critic, considered the musical analogs to the books she read, while another mapped her reads from this year onto constellations. Most people's reading was guided purely by pleasure, or else a desire to better understand events unfolding in their lives or larger the world. Yet others centered their reading around a certain sense of duty: this year one contributor committed to finishing the six Philip Roth novels he had yet to read, an undertaking that he likens to “eating a six-pack of paper towels.” (Lucky for us, he included in his essay his final ranking of Roth's oeuvre.)

The books that populate these essays range widely, though the most commonly noted title this year was Tony Tulathimutte’s story collection Rejection. The work of newly minted National Book Award winner Percival Everett, particularly his acclaimed novel James, was also widely read and written about. And as the genocide of Palestinians in Gaza enters its second year, many contributors sought out Isabella Hammad’s searing, clear-eyed essay Recognizing the Stranger.

Like so many endeavors in our chronically under-resourced literary community, Year in Reading is a labor of love. The Millions is a one-person editorial operation (with an invaluable assist from SEO maven Dani Fishman), and producing YIR—and witnessing the joy it brings contributors and readers alike—has been the highlight of my tenure as editor. I’m profoundly grateful for the generosity of this year’s contributors, whose names and entries will be revealed below over the next three weeks, concluding on Wednesday, December 18. Be sure to subscribe to The Millions’ free newsletter to get the week’s entries sent straight to your inbox each Friday.

—Sophia Stewart, editor

Becca Rothfeld, author of All Things Are Too Small

Carvell Wallace, author of Another Word for Love

Charlotte Shane, author of An Honest Woman

Brianna Di Monda, writer and editor

Nell Irvin Painter, author of I Just Keep Talking

Carrie Courogen, author of Miss May Does Not Exist

Ayşegül Savaş, author of The Anthropologists

Zachary Issenberg, writer

Tony Tulathimutte, author of Rejection

Ann Powers, author of Traveling: On the Path of Joni Mitchell

Lidia Yuknavitch, author of Reading the Waves

Nicholas Russell, writer and critic

Daniel Saldaña París, author of Planes Flying Over a Monster

Lili Anolik, author of Didion and Babitz

Deborah Ghim, editor

Emily Witt, author of Health and Safety

Nathan Thrall, author of A Day in the Life of Abed Salama

Lena Moses-Schmitt, author of True Mistakes

Jeremy Gordon, author of See Friendship

John Lee Clark, author of Touch the Future

Ellen Wayland-Smith, author of The Science of Last Things

Edwin Frank, publisher and author of Stranger Than Fiction

Sophia Stewart, editor of The Millions

A Year in Reading Archives: 2023, 2022, 2021, 2020, 2019, 2018, 2017, 2016, 2015, 2014, 2013, 2011, 2010, 2009, 2008, 2007, 2006, 2005

The Man Who Blew the Dust Off James M. Cain’s Lost Last Novel

1.

Vladimir Nabokov recently did it. So did Ralph Ellison, Roberto Bolaño, David Foster Wallace, and Stieg Larsson. Now an immortal god of noir fiction, James M. Cain, has done it too – published a novel from the grave, a move that's sure to delight Cain's fans while dismaying those who feel that the publishing world should have the decency to let dead authors rest in peace.

Cain's lost last novel is called The Cocktail Waitress. Like two of his early masterpieces, The Postman Always Rings Twice and Double Indemnity, it tells the story of a sexy young woman, Joan Medford, who's caught in a vise between a prosperous older man and a younger, more desirable, more dangerous one. Since this is a James M. Cain novel, you know there will be lust and there will be blood and things will not turn out well for either of these guys. Same goes for Joan Medford's first husband, who is already dead when the book opens.

There are stories behind this book's classic noir story. One is the story of its author, once famous but nearly forgotten late in life, still sweating out the words as his health fails and death closes in. Another is the story of the manuscript – or, more accurately, the manuscripts – the last things Cain produced, which never got published, then got lost for 35 years, then got found. Luckily – or unluckily, depending on your bias – the manuscripts got found by a dedicated Cain fan who also happens to be an accomplished writer and editor. And he was willing to take on the daunting task of sorting out and polishing the chaotic manuscripts, then bringing the finished book to light.

2.

The story of the publication of The Cocktail Waitress began to unfold at the corner of Broadway and 112th Street in New York City on a fall day in 1987, when Charles Ardai, a bookish freshman English major at nearby Columbia University, was walking past a table of used books. The title of a slim volume caught his eye: Double Indemnity. He had never heard of its author, James M. Cain, but he was about to become a hopeless junkie.

"I read it in one gulp and needed more," says Ardai (pronounced ARE-die), now 42. "I found Cain's bleak worldview shockingly sympathetic. His world was brutal, unfair, unjust. As the son of two Holocaust survivors, you learn that the world is an uncaring place. It's indifferent to your suffering."

Ardai, who had started selling articles about video games while still in high school, sold his first short story, "The Long Day," to Ellery Queen's Mystery Magazine for $250 while he was at Columbia. He was specializing in the British romantic poets at the time and embarking on a program to read every word James M. Cain ever published.

After graduation, Ardai put his writing ambitions on hold and went to work for a finance/tech company called the D. E. Shaw Group, where he worked on the early free e-mail service, Juno. Down the hall a co-worker named Jeff Bezos was putting together the concept for an online bookselling service he would eventually call Amazon.

One day Ardai and another co-worker, the graphic designer/novelist Max Phillips, were having a drink and chatting about their shared love for Cain and his pulp peers, the writers of fast-paced, blood-drenched tales that used to appear between colorful paperback covers featuring slinky women wielding a knife or a gun – or a nice dependable baseball bat. The two friends lamented the fact that the genre was in a state of eclipse, and many of the form's masters were either dead or getting there quick.

"There's a body on page one," Ardai says, ticking off pulp fiction's irresistible appeals. "The cover art is classical realism with a heightened sense of sexuality and menace. The stories are heart-stopping, a wonderful blend of high and low culture. Max and I asked ourselves: Why doesn't anyone produce books like that anymore?"

They decided to do it themselves. Phillips did some mock-ups of cover art, and three years later he and Ardai launched a new line, a blend of reprints and paperback originals called Hard Case Crime. Their first book, Grifter's Game by Lawrence Block, has been followed by more than 70 others by such writers as Mickey Spillane, Ed McBain, Donald E. Westlake, Madison Smartt Bell, David Goodis, and Ardai, writing under his own name and the pen name Richard Aleas. Some of the titles will stop your heart, such as Blood on the Mink, The Vengeful Virgin, and The Corpse Wore Pasties. Stephen King's The Colorado Kid has been Hard Case Crime's best-selling title by far, and it became the basis for the TV series Haven, now in its third season on the SyFy channel, for which Ardai has served as consulting producer and occasional scriptwriter.

Which brings us back to James M. Cain.

3.

In 2002, while Hard Case Crime was still in the larval phase, Ardai was exchanging e-mails with Max Allan Collins, a prolific crime writer and dedicated student of the genre. While discussing possible authors for the series, they discovered they shared a passion for Cain's work. This put them in good company. André Gide and Jean-Paul Sartre were also admirers of Cain's stripped-down prose and bleak worldview. So was Albert Camus, who said he used Postman as a model for The Stranger.

Ardai thought he'd read every word Cain ever wrote, but Collins mentioned a book Ardai had never heard of, one that Cain had noted in an interview shortly before his death in 1977, a book that was sketchily summarized in Roy Hoopes's 1987 biography of Cain. The book, Collins told Ardai, was called The Cocktail Waitress.

Ardai then embarked on an odyssey that would last nearly a decade. He started digging for the missing manuscript, contacting Otto Penzler, the founder of Mysterious Press, as well as academics, the Cain estate, book collectors, fellow writers. No one knew a thing. Then serendipity intervened. Ardai's agent, Joel Gotler, inherited the business of an old-school Hollywood agent named H.N. Swanson, who had died in 1991 at the age of 91. Swanson once represented many famous writers, including William Faulkner, Raymond Chandler, and, as it happened, James M. Cain.

"I asked Joel to look into Swanson's files," Ardai said, "and a week later an envelope showed up in the mail. It was a photocopy of The Cocktail Waitress manuscript."

Ardai then learned that there were Cain papers in the Library of Congress, and he promptly took a train to Washington and made a heart-stopping discovery worthy of a pulp novel: more than 100 boxes of papers from all stages of Cain's life, including other completed versions of The Cocktail Waitress, along with partial manuscripts and fragments of the novel, notes Cain wrote to himself, lists of possible names for characters, alternative titles, different versions of key scenes.

"It was like a moment out of Indiana Jones – prying the lid off the sarcophagus, blowing off the dust," Ardai says. "It was breathtaking. I was thrilled. To find new words from an author you thought would never speak again – it was magical."

Ardai spent three months sifting through the drafts and notes, cutting, stitching, smoothing. If anything, he had too much material to sift through. Here's how he describes the arduous editing process in the Afterword to the published book:

Not only did Cain try out multiple variations of key scenes, he went back and forth with regard to his choices.... All of this leaves an editor in a somewhat odd position of having to choose the version of each scene – where there are multiples – that works best in and of itself and also fits best into the overall architecture of the plot. And that means deciding what pieces to leave out, a painful set of decisions. Editing the book was difficult for other reasons as well. Some lines and paragraphs needed to be excised or altered for consistency...or for pacing and focus.... On the other hand, a few excellent scenes Cain wrote in his first draft inexplicably didn't make it into later drafts and I took the opportunity to fit them back in...

I gave particular care to the sections Cain worked over the most himself, aided by the notes he left behind, which ranged from details of setting...to chapter-by-chapter breakdowns of events and motivations...and notes on atmosphere.... It almost felt – almost – like having Cain sitting there with me at the keyboard, watching over my shoulder, keeping me on the straight and narrow.

4.

And now we arrive at an unarguable conclusion and a delicate question. The conclusion is this: While The Cocktail Waitress has its virtues – most notably the unease Joan Medford stirs in the reader, the way it's impossible to know if she's a repeat killer – the book simply is not in a class with Cain's three early masterpieces, Postman, Double Indemnity, and Mildred Pierce. Despite Ardai's deft job of editing a messy mass of material, the book tends to lose its sharpness from time to time. You'll cringe every time Joan Medford says "lo and behold." For me, the setting in a bland Maryland suburb gives the proceedings a fatally tepid feel, the opposite of the smoldering dread and doom that bled through the California sunshine in Cain's dark early masterpieces.

Ardai disagrees, sort of. "Some writers peak early and their powers wane," he says. "Cain tried screenwriting in Hollywood and was a failure. He moved back to his native Maryland, and he hated it. He tried to write a novel set during the Civil War, and it failed. He tried to get labor unions and politics into his fiction. He seemed to have a desire to deal with Big Issues, and he just wasn't good at it. It was almost like he was embarrassed by what he was good at – depicting individuals whose lives are coming apart. With The Cocktail Waitress he was trying to get back to the kind of story that he was known for and that he did best – brutal stories about desperate people in dire circumstances doing terrible things."

The delicate question is this: Shouldn't books that went unpublished in a writer's lifetime, for whatever reason, remain unpublished after the writer's death – especially if the writer expresses the wish that they not see print?

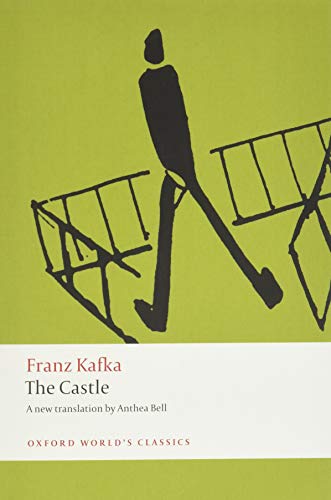

"If an author expressly asks that a book not be published, I would respect that," Ardai says, quickly adding that he believes there are exceptions even to this rule. He cites the case of Franz Kafka, who ordered his friend and biographer, Max Brod, to destroy his unpublished manuscripts after his death. Brod ignored the request, and we now have him to thank for three enduring classics, The Trial, The Castle, and Amerika.

Ardai also cites the more recent case of Vladimir Nabokov, who ordered his family to burn the manuscript of his final, unpublished novel after his death. The "manuscript" consisted of 138 index cards, in no discernible order. Nabokov's son and literary executor, Dmitri, kept the cards in a bank vault, occasionally showing them to scholars after his father died in 1977. Finally, in 2009, Dmitri contravened his father's wishes and published The Original of Laura (A Novel in Fragments). "In fact," David Gates wrote in the New York Times, "it's simply fragments of a novel." Even so, Ardai believes that Max Brod and Dmitri Nabokov did the right thing."If it's a cultural treasure – a book by a Kafka or a Nabokov – I would make an exception," he says. And while he doesn't claim that Cain is in Kafka's and Nabokov's league, he makes no apologies for bringing The Cocktail Waitress into the world.

"I don't think it's a classic," he says, "but I definitely think there are things in it that are exceptional. I'm proud to publish it because of the exceptional parts and because of its historical value. You publish it not to cash in, but because major writers deserve to have their entire catalog available not just to scholars, but to readers. And it's a good read."

No argument there. It falls short of Cain's best work – most books do – but Charles Ardai has done us all a service by unearthing it, lovingly shaping it, and sending it out into the world.

Image Credit: Bill Morris/billmorris52@gmail.com

Shadow of a Doubt: Franz Kafka and TV’s ‘The Killing’

How far would you go to learn the truth? In AMC’s detective drama, The Killing, “the truth” is the identity of 15-year-old Rosie Larsen’s killer in a perpetually-overcast Seattle. Would you risk losing your teenaged son, like Detective Sarah Linden? Ditch your fiancé? Would you work fifty hours straight, like her partner, Detective Stephen Holder? Endanger your sobriety by stepping into the den of your old meth dealer? Would you wrench your family even further apart, like Rosie’s father, Stan Larsen? Would you fight City Hall? Would you give up your badge and your gun?

Would you watch 13 hours of television? 26? 39?

This is, essentially, the question asked of us by The Killing, which just ended its controversial second season. The show began as one of the most critically acclaimed new shows of 2011, nominated for three Critic’s Choice awards and six Emmys. Tim Goodman at The Hollywood Reporter declared it “excellent, absorbing and addictive. When each episode ends, you long for the next – a hallmark of great dramas.” But a few months later, that same reviewer was singing a different tune. “Did The Killing Just Kill Itself?” his review of the first season finale asked.

For those who have not become as addicted to this show as I have, all you really need to know is that, after thirteen incredibly tense episodes, all the evidence began to point toward the charismatic Mayoral candidate, Darren Richmond. Most damningly, a photo from a toll booth showed Richmond driving away from the scene of Rosie’s abduction in the car where her body was later bound inside the trunk. But then, seconds before the credits rolled, Detective Linden discovered the photo was a fake. Meanwhile the innocent Richmond was shot by a friend of the Larsen family. The season ended, and the show’s fans rioted.

When I first began to watch The Killing two months ago, I told a friend who’d been watching since day one. His reaction was vehement. “Goddamn FUCK THE KILLING. I keep watching it and it keeps NOT GOING ANYWHERE. I keep thinking “OK, THIS is it” and theeennn… nope. And yet I cannot stop watching.” This same friend directed me to the website, fuckthekilling.com, which is essentially a short, explicit open letter to the show from its fans.

Most critics were just as outraged. Many cited the fact that The Killing is based on a Danish TV drama Forbrydelsen, or “The Crime”, and the pilot episodes were nearly identical, shot-for-shot. They argue that while the first season of Forbrydelsen ended satisfyingly, by disclosing the true identity of the murderer, The Killing broke that unspoken pact between itself and its audience: watch this show for 13 weeks and you will be rewarded with the truth. Subverting our expectations has brought great acclaim to other AMC shows like Mad Men and Breaking Bad, but with The Killing, the move appears to have backfired.

As the second season began, Goodman issued the show a stern warning. “By not revealing who killed Rosie Larsen in season one, this season could implode.” But in this same breath he complained that Veena Sud was compounding the problem by speaking out and directly assuring fans that the Larsen case would be solved by the end of season two. This creates a major suspense problem. “In the first 12 episodes, viewers will never believe a suspect is about to be revealed or that detectives closing in on a suspect in, say, episode seven, has any real relevancy. It certainly doesn’t make that storytelling immediately essential. Secondly, it’s telling viewers that they will be rewarded with a resolved mystery after 26 hours of television. If you see the appeal in any of this, please fire off a flare.”

Well, Tim, consider this my flare.

Think about it. How can we be upset when the truth is withheld just when we most expect it, and when someone promises that it will be delivered, right on time? But we in the audience always want to have it both ways: we want to have our expectations met, and at the same time, confounded. Novelist Elizabeth Bowen observed that “Story involves action[…] towards an end not to be forseen (by the reader) but also towards an end which, having been reached, must be seen to have been from the start inevitable.” Figuring how to get out of this double-bind has been the failing of many a writer. In all mediums, we reserve a large segment of our judgment until we see how well an entertainment ends. A great ending sends reverberations back through everything that transpired to reach it.

In the second season finale on Sunday night, The Killing achieved one of these great endings for the Larsen case. Sud kept her promise and revealed the truth about Rosie’s murder. The conclusion was satisfying, in that it did not satisfy. Rosie’s killing turned out to be caused by two different villains, one somewhat expected and the other utterly unexpected. In the end, these truths bring neither clarity nor comfort. Not to the Larsens or to the detectives. The truth behind Rosie’s killing turn out to be so meaningless and darkly ironic that we almost wish we didn’t know it. We know how Detective Holder feels as he shakes his head in his dark office. “Just the wrong place at the wrong time. Sometimes it just comes down to that I guess. Just randomness.” He comes to understand, as we must, that the truth is never as holy a grail as the quest we took to find it.

“Sounds like LOST,” another friend of mine scoffed, when I described my love of The Killing, “Never making that mistake again. LOST took away my ability to trust other people.”

Like The Killing, LOST steadily alienated its huge initial audience when writers decided to take the show in unexpected directions and then readily admitted to viewers that they did not have the truth about the mysterious island quite worked out, but that they’d figure it out as they went. The result was seven seasons filled with great drama and action, but also dead-end plots, quickly forgotten clues, and pointless characters. All of this stalling produced one loose end after the next, and there was simply no way to tie them all together in the end.

Tim Goodman likewise criticized the first season of The Killing for introducing too many “red herrings.” A red herring is a staple in most mystery stories. It is a misleading clue planted to distract us from the eventual truth. It is a kind of intended misdirection, which keeps an audience on their toes. The term originates in the training of dogs. A red herring would be run along the ground away from the scent that the dog was meant to follow. The idea was to train the dogs to eventually recognize when they were being fooled.

But while LOST dropped misleading clues haphazardly here and there to buy more time, The Killing has thus far used red herrings intentionally to lead both viewers and detectives in the wrong direction, not simply to kill time, but to make us interrogate our own assumptions about these dead-ends.

Did candidate Richmond really fit the bill? Wouldn’t it have been pretty lame for the oh-so-charming politician to wind up being a sociopathic killer? And why would he have been stupid enough to arbitrarily snuff out a call girl, two weeks before his election? And did it ever make sense that sweet, sheltered Rosie Larsen would work part-time as a high-priced underage hooker? Sud turned Richmond into yet another red herring, and this should have made us, like the detectives, wonder why we were so desperate for the truth that we’d have preferred that patently ridiculous answer. The innocent Richmond was shot and crippled for our eagerness, just as the previous nonsensical suspect, Rosie’s teacher Bennett Ahmed, was beaten nearly to death. Did anyone really think they’d make him into a secret terrorist? Now that we know the truth, it is easier to see how red those herrings really were.

It is telling that Veena Sud’s upcoming film project is a remake of the Hitchcock classic Suspicion. Hitchcock was the rare artist who managed to entertain audiences and subvert their expectations at the same time. Hitchcock achieved this most often by using a “MacGuffin,” allowing the initial mystery itself to become the red herring. Use a MacGuffin right and you can accomplish almost anything; do it wrong and your audience will never trust you again. Just ask M. Night Shyamalan.

The Killing is often compared to the Hitchcockian TV drama, Twin Peaks, which captivated America in 1990. Director David Lynch brought us Detective Dale Cooper, who was also searching for the killer of a young girl deep in the woods of Washington State. Twin Peaks used Laura Palmer’s murder as a MacGuffin to lead its viewers closer to the bizarre townsfolk, through surreal dreams, and chasing after a one-armed man. It became the most popular show on American television, but when Lynch ended his first season without delivering answers, audiences were rabid. Lynch gave in and revealed early in the second season that grieving father Leland Palmer had killed his own daughter.

And after this reveal, Twin Peaks lost its audience anyway. Soon the show ranked 85th out of 89 shows on the air. Now that Veena Sud has kept her word and revealed the killer, she runs the risk of finding her audience evaporating just like Lynch’s.

Fans and critics might well be outraged at The Killing’s anticlimax. Some might even wish Sud had decided to just leave us all in suspense for another year. But hopefully this ending will encourage viewers to stop trying so hard to see The Killing as a typical police drama and wake up to the fact that it long-ago metamorphosed into something much more fascinating. It has been, from the start, a show that makes us question – like Detectives Linden and Holder – the value of the truth, and what we will invest of ourselves in order to know it.

Last year, in an interview with Alan Sepinwall, Veena Sud defended the integrity of the show. “We said from the very beginning this is the anti-cop cop show. It's a show where nothing is what it seems, so throw out expectations. We will not tie up this show in a bow. There are plenty of shows that do that, in 45 minutes or whatever amount of time, where that is expected and the audience can rest assured that at the end of blank, they will be happy and they can walk away from their TV satisfied. This is not that show.”

Veena Sud worked for four years as a writer and producer for the CBS cop show Cold Case, a cop show which follows a tight formula: a long-forgotten case somehow surfaces and eventually is solved through the use of “modern techniques” of DNA processing and microfiber analysis. In truth, cold cases are rarely solved, and lawyers today cite The CSI Effect to explain how juries accustomed to TV crime dramas have come to expect an unrealistic level of certainty in evidence. An FBI study done in 2010 showed that since 1980 only 63% of murders have been solved, nationwide. This ranges from highs of 82% in North Las Vegas and lows of only 21% in Detroit. Perhaps this explains why we are so buoyed by the prospect that a single hair follicle might lead detectives to a killer within hours of a murder. No one ever said red herrings didn’t smell good.

Perhaps Sud asked herself what it says about audiences that we will watch essentially the same unrealistic episode of Cold Case, again and again? That show ran for seven years. CSI has run for thirteen years so far and has spun off two other series, both still running. Law & Order ended after twenty-years, after spinning of four new series. There’s NCIS, times two. Bones. Criminal Minds, times two. Hawaii Five-O all over again. Each show, in its own way, comfortingly repeats the formula, delivering the truth right on time, usually with an arched eyebrow and a wry quip. Perhaps The Killing isn’t breaking a pact with us, but staging an intervention.

It’s suggestive that Detective Holder is a former meth addict, and some of the dialogue between him and Linden revolves around the nature of addiction: what you’ll give up for your high and what rock-bottom looks like. Linden too, is depicted as an addict, not to drugs but to the case. She is, like us, addicted to the truth. Years earlier, Linden had a similar case which was never solved, and it landed her in a psychiatric institution. Then, facing the impossibility of knowing the truth drove Linden crazy. But at the end of the second season, she sees that knowing the truth is almost as unnerving. When Holder insists, for the second time that day, “We got the bad guy,” Linden’s only response is a chilly, “Yeah, who’s that?”

Because The Killing began as an adaptation of the Danish TV drama Forbrydelsen, many compare it to Stieg Larsson’s Girl With the Dragon Tattoo books. But while it has some of that same icy edge and atmosphere, I think a better comparison is to the novels of another introverted writer from a gloomy European locale, whose work also went on to great acclaim only after his death: Franz Kafka.

Kafka’s most famous story, The Metamorphosis, is about a man who wakes up one day mysteriously transformed into a bug. But this strange mutation is a MacGuffin. We want to find out how poor Gregor turned into a bug, and so we delve deeper into Gregor’s sad predicament. Like Hitchcock’s The Birds, Kafka gives no explanation in the end, by which time we are so moved and awestruck that we’ve forgotten what we came for.

Another classic tale, "In the Penal Colony," involves a man journeying to a remote prison to see a machine of elegant torture. An Officer there explains that it painfully tattoos a criminal with the phrase “Be Just” until they eventually receive a mystical revelation and die in ecstasy. The Officer is so excited by this magnificent torture that he jumps into the machine – only it breaks and kills him before he can find out truth the criminals received.

The Killing would fit right in with Kafka’s two best-known novels, The Trial and The Castle, which each feature a protagonist known as “K”. Both novels stretch on for hundreds of pages as K attempts to learn some sort of unobtainable truth. In this absurd pursuit K loses everything, breaks down utterly, and gets nowhere. And because neither novel was even finished at the time of Kafka’s death in 1924, even K’s total ruination is never quite completed.

Both novels show K toiling futilely against the systems of the law. In The Killing the inverse proposition is examined: two lawmen attempt to bring justice and to uncover an important truth. Their truth becomes just as elusive as the one sought by poor K. The deeper they dig, the further away it somehow gets.

Modern detective work, despite microfibers and DNA, is still rooted in the rational principles of the 16th century scientific revolution, when thinkers began to re-embrace the Classical idea that logical inquiry could lead us to the truth. The scientific method makes a kind of pact with us: collect evidence and probe it until the rational world gives up its secrets. Develop a logical hypothesis and test it out. If it fails, then you have at least eliminated something that is untrue. Start over. Try again. Keep looking. You’ve almost got it.

Four centuries later, we live in a world in which astronomers have discovered incredible things about the nature of matter, right down to the tiniest subatomic particle, and charted the expanses of the universe for light-years in all directions. And yet each answer has given us a hundred new mysteries to solve. We’ve interrogated the human body down to the smallest acellular organisms, and for each truth we have learned, ten more questions have popped out from behind it. We’ve learned much, but for all that we understand, perhaps the greatest thing we’ve learned is how much more there is to learn.

In the case of killings, there will are always unsolved cases, wrongful convictions, and unreliable witnesses. But even when we do know, beyond the shadow of a doubt, that one person killed a second person, and we arrest and punish that first person, there’s still so much we don’t know. The Killing makes this uncertainty its very heart. Is imprisoning the killer any justice. Is killing them? Can we ever understand how the killer did what they did? What is the measure of that lost life? What is the measure of the killer’s?

Don’t get me wrong. The pursuit of truth is a noble ambition. Asking if this pursuit is futile is itself but one more truth we should keep pursuing.

People often mistake Kafka for a nihilist, but his books can be very uplifting. In echoing the human struggling we often feel, we can feel less alone in that struggle – we may even laugh at it. Novelist David Foster Wallace explained how he would get his students to see the humor in Kafka. “You can ask them to imagine his stories as a kind of door. To envision us approaching and pounding on this door, increasingly hard, pounding and pounding, not just wanting admission but needing it; we don’t know what it is, but we can feel it, this total desperation to enter, pounding and ramming and kicking. That, finally, the door opens… and it opens outward – we’ve been inside what we wanted all along. Das ist komisch.” (Roughly translated, this means, “That’s pretty funny.”)

The Killing does not want to tell us an easy truth, but a difficult one. Hollywood Reporter Tim Goodman has himself argued that difficult shows can be worth the effort it takes to understand them. “You know what else is difficult? The first chapters of War and Peace. Also, great gobs of Remembrance of Things Past. Did you also know that diving in to William Faulkner can leave you wondering what the hell is going on?”

Plenty of us, of course, don’t have the patience to read the classics, or to even watch The Killing, but this does not mean that we wouldn’t be rewarded if we developed some. By embracing the entertainments of difficulty, we can learn, like Detectives Linden and Holder, to become more aware in our pursuit of the truth. We can begin to see that we are the ones who are forever tattooing that fervent Kafkaesque wish upon the world, “Be Just.”

Dance in Purgatory: László Krasznahorkai’s Satantango

If there is one element of László Krasznahorkai’s prose to which critics are most often drawn, it is the length of his sentences. Indeed, they are long: comma-spliced and unrelenting. They run on, at times, for pages, requiring diligence of even the patient reader. George Szirtes, the award-winning British poet who has translated three of Krasznahorkai’s novels, describes the effect as a “slow lava flow of narrative, a vast black river of type.” But Krasznahorkai’s prose is not singular in this regard. Post-war Europe has produced a cabal of writers responsible for similar feats of syntax: Thomas Bernhard, W.G. Sebald, Bohumil Hrabal, and Witold Gombrowicz, to name a few. Amid such company, Krasznahorkai feels a bit like the uncle whose throat-clearing at holiday dinners causes those at the table to shift uneasily in their seats. He is obsessed as much with the extremes of language as he is with the extremes of thought, with the very limits of people and systems in a world gone mad — and it is hard not to be compelled by the haunting clarity of his vision.

Satantango is the most recent of Krasznahorkai’s novels to appear in English, twenty-seven years after its publication in Hungary. It will be released this February by New Directions, the publisher responsible for the rest of Krasznahorkai’s English-language oeuvre: The Melancholy of Resistance was first published in 1998 (in Hungarian in 1989), followed by War & War in 2006 (in Hungarian in 1999), and AnimalInside, a slim pamphlet-sized book translated by Ottilie Mulzet with art from Max Neumann, in 2010. Satantango is perhaps best known as the seven-hour film of the same name by avant-garde filmmaker Béla Tarr, with whom Krasznahorkai often collaborates. In Tarr’s long, spare, black-and-white shots, the movement of Krasznahorkai’s sentences — if not their vitality or their rhythms — find an appropriate analogue:

He decided to watch everything every carefully and to record it constantly, all with the aim of not missing the smallest detail, because he realized with a shock that to ignore the apparently insignificant was to admit that one was condemned to sit defenseless on the parapet connecting the rising and falling members of the bridge between chaos and comprehensible order. However apparently insignificant the event, whether it be the ring of tobacco ash surrounding the table, the direction from which the wild geese first appeared, or a series of seemingly meaningless human movements, he couldn’t afford to take his eyes off it and must note it all down, since only by doing so could he hope not to vanish one day and fall a silent captive to the infernal arrangement whereby the world decomposes but is at the same time constantly in the process of self-construction.

The sentences have what the critic James Wood, in his The New Yorker essay last July, called a “self-correcting shuffle, as if something were genuinely being worked out, and yet, painfully and humorously, these corrections never result in the correct answer.” One sees similarly recursive patterns in Bernhard and can spot his influence in Krasznahorkai’s later work, most notably in the mad, maddening, György Korin, the protagonist of War & War, to whose machinations Wood refers. Satantango, by contrast, is a quieter book. It is more Beckett-like its sparseness, as though Krasznahorkai, for his novelistic debut, chose to privilege the formal architecture of the novel, the neatness of its structure, over the extremity of his prose. The result is a more mannered brilliance.

Satantango begins with the epigraph: “In that case, I’ll miss the thing by waiting for it.” In the original Hungarian, the line is attributed to “F.K.” — Franz Kafka — borrowed from his novel The Castle. It is unclear why Szirtes has chosen to translate the selection this way and also to leave it unaccredited. In that scene, while waiting for Klamm outside an inn, K. is approached by a man who insists that K. come with him. K. refuses, and the man cannot understand why. “But then I’ll miss the person I’m waiting for,” says K. “You’ll miss him whether you wait or go,” the man replies. Here, in Mark Harman’s translation, K. says, “Then I would rather miss him as I wait.” The implication is comical: faced with evidence to the contrary, we would prefer to believe ourselves better off should we elect to stay. And yet given the choice, who would choose otherwise?

The inhabitants of the nameless, rain-battered village in which Satantango is set are caught in a similarly fraught waiting game. There is the lame Futaki; the libidinous Mrs. Schmidt; the neglected child, Esti, who kills her cat with rat poison; the god-fearing Mrs. Halics; the landlord; and the doctor who, in order to “preserve his failing memory against the decay that consumed everything around him,” maintains extensive dossiers on them all. They are connected by the spiritual poverty — though they suffer different strains of it — that has settled over “the estate.” The estate resembles a failed collective; it has gone to ruin after the closing of a nearby mill, the circumstances of which, like the history of this seemingly forgotten place, are alluded to — often in dreams. Those who have remained on the land do little more than pick fights, sleep with one another’s wives, and toss back shots of pálinka at the landlord’s bar, that is, until Irimiás and Petrina, both thought to be dead, are spotted on the road to the estate. News of their alleged resurrection spreads fast, and with it, the potential for deliverance or destruction. As the citizens of the town continue to wait (a premise owing much to Beckett and Bulgakov), dancing drunkenly late into the night — “Time for a tango!” one man shouts — Mrs. Halics wonders, “Where was the hellfire that would surely destroy them all? . . . How could they look down on this seething nest of wickedness ‘straight out of Sodom and Gomorrah’ and yet do nothing?”

It is at this point in the book that the novel’s two main figures, Irimiás and Petrina, arrive. In a long and impassioned speech, Irimiás offers absolution, promising to lead the villagers to a nearby estate, “a small island for a few people with nothing left to lose, a small island free of exploitation, where people work for, not against each other, where everyone has plenty and peace and security like a proper human being.” But if Irimiás is a prophet, he is a false one. One sees behind his words the same illusions of the very system which has, not long before, broken the villagers themselves. Here, as the people of the town rally behind Irimiás with renewed hope, we begin to get a feel for the dance. The structure of the novel mimics that of the tango: the chapters go six steps forward (part one) and six steps back (part two), with the pivot marked by the arrival of Irimiás and Petrina, and the ending, by the repetition of the first two pages, as if the dance were to continue on in a closed purgatorial loop, the day of judgment remaining just out of reach. And so we, like the denizens of the town, begin the dance again: six steps forward, forever hopeful, forever waiting.

The Burden of Meaningfulness: David Foster Wallace’s The Pale King

In the late David Foster Wallace’s unfinished novel The Pale King, IRS employee Claude Sylvanshine is a “fact psychic.” This means he is periodically overwhelmed with cascades of “ephemeral, useless, undramatic, distracting” information about other people. When he eats a cupcake, for instance, he knows where it comes from, who baked it, and a sprinkling of vital statistics about its baker–his “weight, shoe size, bowling average, American Legion career batting average.” As the details proliferate, it becomes obvious that the sum does not add up to a person. What Sylvanshine learns about others isn’t, and can’t be, insight: it arrives with no context and no narrative, touched off by minimal contact or none at all, and he has no means of organizing or using what he knows. The information is raw, “fractious, boiling,” and its accumulation oppresses him. Some of it presents visually, “queerly backlit, as by an infinitely bright light an infinite distance away.” Sylvanshine’s gift gives him a headache.

Wallace himself, of course, was something of a fact psychic, possessed of freakishly sensitive awareness and unsure of its human use. To read his work is to encounter great drifts of detail, drifts which have contributed, along with his books’ sheer length, to the perception of his work as excessive or maximalist. Wyatt Mason notes in The New York Review of Books that those who characterize Wallace’s fiction this way sometimes imply a failure of control or restraint, as if “however smart he was, he wasn’t smart enough to write fiction that didn’t distract the reader with yieldless shows of virtuosity.” But Wallace’s canonization, now close to complete, means these criticisms no longer have much bite. Mostly we feel that Wallace’s headlong, encyclopedic, garrulous manner was born of necessity, not indulgence, that the stylistic innovations, including the massed detail, grew not from vanity but from some kind of mimetic imperative to reflect back to us our dizzy, painful, teeming, inconclusive lives.

This vision of Wallace is of an artist in full possession of his art, his every choice considered and confident. Even so, D.T. Max, writing for The New Yorker, finds traces in the years before Wallace’s death of a different sort of author, one who had come to doubt the style he’d become known for and grown dissatisfied with himself as a writer, even believing, Max suggests, that he might not be “the kind of person who could write the novel he wanted to write.” How deep this unease went it’s impossible to say, though it does seem that Wallace was conscious early on of the costs exacted by his stylistic choices. In a 1993 interview with Larry McCaffery, he worried about writing “sentences that [were] syntactically not incorrect but still a real bitch to read. Or bludgeoning the reader with data. Or devoting a lot of energy to creating expectations and then taking pleasure in disappointing them.” Still, if he was aware of the risks of his approach, he seemed certain, at least in 1993, that they were worth running. About his project at the time (probably Infinite Jest), he said, “Whether I can provide a payoff and communicate a function rather than just seem jumbled and prolix is the issue that’ll decide whether the thing I’m working on now succeeds or not.”

An unfinished novel almost by definition doesn’t provide a payoff or carry out its “function.” This means we can’t know whether the unfinished book was also unfinishable, an insoluble puzzle. (Though some novels--Kafka’s Castle for example--seem more eloquent and even “successful” for being incomplete.) Certainly Wallace had set himself a problem masochistic or quixotic in its difficulty: how to write an interesting novel about that byword for tedium, the IRS? And how to write a religious novel–which is what The Pale King is, in its preoccupation with grace, illumination, and purpose–about the most disenchanted and secular of professions, namely accounting? Employees of the IRS, fact psychics or not, don’t want for hard numbers. The question is whether, along with the data, they can acquire a sense of vocation and vision, of meaningful work in a meaningful world. It is a question whose implications point inward, to the novelist’s own profession, and outward, to the status of human activity generally in what we have come to call an “information society.”

If Infinite Jest was about addiction, entertainment and distraction–about avoiding the truth–The Pale King is about the opposite phenomena of boredom and attention, about staring at the world instead of looking away. And if Infinite Jest was quintessentially a novel about fuckups and misfits, The Pale King is a novel about reliable employees, people who go to work each day and get there on time. Claude Sylvanshine is one of a handful of primary characters, low-level IRS employees mainly (many of them rote examiners, or “wigglers,” in IRS lingo), whose stories appear and reappear over the course of the book’s 539 pages. Among these narratives, assembled from Wallace’s manuscripts and notes by his longtime editor Michael Pietsch, glimmers a constellation of minor characters, all linked by their association with “the Service.” The relations among the cast blink on and off as the book progresses, alternately intensifying or falling away. There is no central protagonist per se, unless you count David Wallace, the self-described author of what he claims is a memoir written primarily for financial gain.