Mentioned in:

A Year in Reading: 2024

Welcome to the 20th (!) installment of The Millions' annual Year in Reading series, which gathers together some of today's most exciting writers and thinkers to share the books that shaped their year. YIR is not a collection of yearend best-of lists; think of it, perhaps, as an assemblage of annotated bibliographies. We've invited contributors to reflect on the books they read this year—an intentionally vague prompt—and encouraged them to approach the assignment however they choose.

In writing about our reading lives, as YIR contributors are asked to do, we inevitably write about our personal lives, our inner lives. This year, a number of contributors read their way through profound grief and serious illness, through new parenthood and cross-country moves. Some found escape in frothy romances, mooring in works of theology, comfort in ancient epic poetry. More than one turned to the wisdom of Ursula K. Le Guin. Many describe a book finding them just when they needed it.

Interpretations of the assignment were wonderfully varied. One contributor, a music critic, considered the musical analogs to the books she read, while another mapped her reads from this year onto constellations. Most people's reading was guided purely by pleasure, or else a desire to better understand events unfolding in their lives or larger the world. Yet others centered their reading around a certain sense of duty: this year one contributor committed to finishing the six Philip Roth novels he had yet to read, an undertaking that he likens to “eating a six-pack of paper towels.” (Lucky for us, he included in his essay his final ranking of Roth's oeuvre.)

The books that populate these essays range widely, though the most commonly noted title this year was Tony Tulathimutte’s story collection Rejection. The work of newly minted National Book Award winner Percival Everett, particularly his acclaimed novel James, was also widely read and written about. And as the genocide of Palestinians in Gaza enters its second year, many contributors sought out Isabella Hammad’s searing, clear-eyed essay Recognizing the Stranger.

Like so many endeavors in our chronically under-resourced literary community, Year in Reading is a labor of love. The Millions is a one-person editorial operation (with an invaluable assist from SEO maven Dani Fishman), and producing YIR—and witnessing the joy it brings contributors and readers alike—has been the highlight of my tenure as editor. I’m profoundly grateful for the generosity of this year’s contributors, whose names and entries will be revealed below over the next three weeks, concluding on Wednesday, December 18. Be sure to subscribe to The Millions’ free newsletter to get the week’s entries sent straight to your inbox each Friday.

—Sophia Stewart, editor

Becca Rothfeld, author of All Things Are Too Small

Carvell Wallace, author of Another Word for Love

Charlotte Shane, author of An Honest Woman

Brianna Di Monda, writer and editor

Nell Irvin Painter, author of I Just Keep Talking

Carrie Courogen, author of Miss May Does Not Exist

Ayşegül Savaş, author of The Anthropologists

Zachary Issenberg, writer

Tony Tulathimutte, author of Rejection

Ann Powers, author of Traveling: On the Path of Joni Mitchell

Lidia Yuknavitch, author of Reading the Waves

Nicholas Russell, writer and critic

Daniel Saldaña París, author of Planes Flying Over a Monster

Lili Anolik, author of Didion and Babitz

Deborah Ghim, editor

Emily Witt, author of Health and Safety

Nathan Thrall, author of A Day in the Life of Abed Salama

Lena Moses-Schmitt, author of True Mistakes

Jeremy Gordon, author of See Friendship

John Lee Clark, author of Touch the Future

Ellen Wayland-Smith, author of The Science of Last Things

Edwin Frank, publisher and author of Stranger Than Fiction

Sophia Stewart, editor of The Millions

A Year in Reading Archives: 2023, 2022, 2021, 2020, 2019, 2018, 2017, 2016, 2015, 2014, 2013, 2011, 2010, 2009, 2008, 2007, 2006, 2005

The Great Fall 2024 Book Preview

With the arrival of autumn comes a deluge of great books. Here you'll find a sampling of new and forthcoming titles that caught our eye here at The Millions, and that we think might catch yours, too. Some we’ve already perused in galley form; others we’re eager to devour based on their authors, plots, or subject matters. We hope your next fall read is among them.

—Sophia Stewart, editor

October

Season of the Swamp by Yuri Herrera, tr. Lisa Dillman [F]

What it is: An epic, speculative account of the 18 months that Benito Juárez spent in New Orleans in 1853-54, years before he became the first and only Indigenous president of Mexico.

Who it's for: Fans of speculative history; readers who appreciate the magic that swirls around any novel set in New Orleans. —Claire Kirch

The Black Utopians by Aaron Robertson [NF]

What it is: An exploration of Black Americans' pursuit and visions of utopia—both ideological and physical—that spans the Reconstruction era to the present day and combines history, memoir, and reportage.

Who it's for: Fans of Saidiya Hartman's Wayward Lives, Beautiful Experiments and Kristen R. Ghodsee's Everyday Utopia. —Sophia M. Stewart

The Third Realm by Karl Ove Knausgaard, tr. Martin Aitken [F]

What it is: The third installment in Knausgaard's Morning Star series, centered on the appearance of a mysterious new star in the skies above Norway.

Who it's for: Real Knausgaard heads only—The Wolves of Eternity and Morning Star are required reading for this one. —SMS

Brown Women Have Everything by Sayantani Dasgupta [NF]

What it is: Essays on the contradictions and complexities of life as an Indian woman in America, probing everything from hair to family to the joys of travel.

Who it's for: Readers of Durga Chew-Bose, Erika L. Sánchez, and Tajja Isen. —SMS

The Plot Against Native America by Bill Vaughn [F]

What it is: The first narrative history of Native American boarding schools— which aimed "civilize" Indigenous children by violently severing them from their culture— and their enduring, horrifying legacy.

Who it's for: Readers of Ned Blackhawk and Kathleen DuVal. —SMS

The Mighty Red by Louise Erdrich [F]

What it is: Erdrich's latest novel set in North Dakota's Red River Valley is a tale of the intertwined lives of ordinary people striving to survive and even thrive in their rural community, despite environmental upheavals, the 2008 financial crisis, and other obstacles.

Who it's for: Readers of cli-fi; fans of Linda LeGarde Grover and William Faulkner. —CK

The Position of Spoons by Deborah Levy [NF]

What it is: The second book from Levy in as many years, diverging from a recent streak of surrealist fiction with a collection of essays marked by exceptional observance and style.

Who it's for: Close lookers and the perennially curious. —John H. Maher

The Bog Wife by Kay Chronister [F]

What it's about: The Haddesley family has lived on the same West Virginia bog for centuries, making a supernatural bargain with the land—a generational blood sacrifice—in order to do so—until an uncovered secret changes everything.

Who it's for: Readers of Karen Russell and Jeff VanderMeer; anyone who has ever used the phrase "girl moss." —SMS

The Great When by Alan Moore [F]

What it's about: When an 18-year old book reseller comes across a copy of a book that shouldn’t exist, it threatens to upend not just an already post-war-torn London, but reality as we know it.

Who it's for: Anyone looking for a Sherlock Holmes-style mystery dipped in thaumaturgical psychedelia. —Daniella Fishman

The Message by Ta-Nehisi Coates [NF]

What it's about: One of our sharpest critical thinkers on social justice returns to nonfiction, nearly a decade after Between the World and Me, visiting Dakar, to contemplate enslavement and the Middle Passage; Columbia, S.C., as a backdrop for his thoughts on Jim Crow and book bans; and the Israeli-occupied West Bank, where he sees contemporary segregation in the treatment of Palestinians.

Who it’s for: Fans of James Baldwin, George Orwell, and Angela Y. Davis; readers of Nikole Hannah-Jones’s The 1619 Project and Isabel Wilkerson’s Caste, to name just a few engagements with national and racial identity. —Nathalie op de Beeck

Abortion by Jessica Valenti [NF]

What it is: Columnist and memoirist Valenti, who tracks pro-choice advocacy and attacks on the right to choose in her Substack, channels feminist rage into a guide for freedom of choice advocacy.

Who it’s for: Readers of Robin Marty’s The New Handbook for a Post-Roe America, #ShoutYourAbortion proponents, and followers of Jennifer Baumgartner’s [I Had an Abortion] project. —NodB

Gifted by Suzuki Suzumi, tr. Allison Markin Powell [F]

What it's about: A young sex worker in Tokyo's red-light district muses on her life and recounts her abusive mother's final days, in what is Suzuki's first novel to be translated into English.

Who it's for: Readers of Susan Boyt and Mieko Kanai; fans of moody, introspective fiction; anyone with a fraught relationship to their mother. —SMS

Childish Literature by Alejandro Zambra, tr. Megan McDowell [F]

What it is: A wide-ranging collection of stories, essays, and poems that explore childhood, fatherhood, and family.

Who it's for: Fans of dad lit (see: Lucas Mann's Attachments, Keith Gessen's Raising Raffi, Karl Ove Knausgaard's seasons quartet, et al). —SMS

Books Are Made Out of Books ed. Michael Lynn Crews [NF]

What it is: A mining of the archives of the late Cormac McCarthy with a focus on the famously tight-lipped author's literary influences.

Who it's for: Anyone whose commonplace book contains the words "arquebus," "cordillera," or "vinegaroon." —JHM

Slaveroad by John Edgar Wideman [F]

What it is: A blend of memoir, fiction, and history that charts the "slaveroad" that runs through American history, spanning the Atlantic slave trade to the criminal justice system, from the celebrated author of Brothers and Keepers.

Who it's for: Fans of Clint Smith and Ta-Nehisi Coates. —SMS

Linguaphile by Julie Sedivy [NF]

What it's about: Linguist Sedivy reflects on a life spent loving language—its beauty, its mystery, and the essential role it plays in human existence.

Who it's for: Amateur (or professional) linguists; fans of the podcast A Way with Words (me). —SMS

An Image of My Name Enters America by Lucy Ives [NF]

What it is: A collection of interrelated essays that connect moments from Ives's life to larger questions of history, identity, and national fantasy,

Who it's for: Fans of Ives, one of our weirdest and most wondrous living writers—duh; anyone with a passing interest in My Little Pony, Cold War–era musicals, or The Three Body Problem, all of which are mined here for great effect. —SMS

Women's Hotel by Daniel Lavery [F]

What it is: A novel set in 1960s New York City, about the adventures of the residents of a hotel providing housing for young women that is very much evocative of the real-life legendary Barbizon Hotel.

Who it's for: Readers of Mary McCarthy's The Group and Rona Jaffe's The Best of Everything. —CK

The World in Books by Kenneth C. Davis [NF]

What it is: A guide to 52 of the most influential works of nonfiction ever published, spanning works from Plato to Ida B. Wells, bell hooks to Barbara Ehrenreich, and Sun Tzu to Joan Didion.

Who it's for: Lovers of nonfiction looking to cover their canonical bases. —SMS

Blue Light Hours by Bruna Dantas Lobato [F]

What it's about: Through the emanating blue-glow of their computer screens, a mother and daughter, four-thousand miles apart, find solace and loneliness in their nightly Skype chats in this heartstring-pulling debut.

Who it's for: Someone who needs to be reminded to CALL YOUR MOTHER! —DF

Riding Like the Wind by Iris Jamahl Dunkle [NF]

What it is: The biography of Sanora Babb, a contemporary of John Steinbeck's whose field notes and interviews with Dust Bowl migrants Steinbeck relied upon to write The Grapes of Wrath.

Who it's for: Steinbeck fans and haters alike; readers of Kristin Hannah's The Four Winds and the New York Times Overlooked column; anyone interested in learning more about the Dust Bowl migrants who fled to California hoping for a better life. —CK

Innie Shadows by Olivia M. Coetzee [F]

What it is: a work of crime fiction set on the outskirts of Cape Town, where a community marred by violence seeks justice and connection; also the first novel to be translated from Kaaps, a dialect of Afrikaans that was until recently only a spoken language.

Who it's for: fans of sprawling, socioeconomically-attuned crime dramas a la The Wire. —SMS

Dorothy Parker in Hollywood by Gail Crowther [NF]

What it is: A history of the famous wit—and famous New Yorker—in her L.A. era, post–Algonquin Round Table and mid–Red Scare.

Who it's for: Owners of a stack of hopelessly dog-eared Joan Didion paperbacks. —JHM

The Myth of American Idealism by Noam Chomsky and Nathan J. Robinson [NF]

What it is: A potent critique of the ideology behind America's foreign interventions and its status as a global power, and an treatise on how the nation's hubristic pursuit of "spreading democracy" threatens not only the delicate balance of global peace, but the already-declining health of our planet.

Who it's for: Chomskyites; policy wonks and casual critics of American recklessness alike. —DF

Mysticism by Simon Critchley [NF]

What it is: A study of mysticism—defined as an experience, rather than religious practice—by the great British philosopher Critchley, who mines music, poetry, and literature along the way.

Who it's for: Readers of John Gray, Jorge Luis Borges, and Simone Weil. —SMS

Q&A by Adrian Tomine [NF]

What it is: The Japanese American creator of the Optic Nerve comic book series for D&Q, and of many a New Yorker cover, shares his personal history and his creative process in this illustrated unburdening.

Who it’s for: Readers of Tomine’s melancholic, sometimes cringey, and occasionally brutal collections of comics short stories including Summer Blonde, Shortcomings, and Killing and Dying. —NodB

Sonny Boy by Al Pacino [NF]

What it is: Al Pacino's memoir—end of description.

Who it's for: Cinephiles; anyone curious how he's gonna spin fumbling Diane Keaton. —SMS

Seeing Baya by Alice Kaplan [NF]

What it is: The first biography of the enigmatic and largely-forgotten Algerian artist Baya Mahieddine, who first enchanted midcentury Paris as a teenager.

Who it's for: Admirers of Leonora Carrington, Hilma af Klint, Frida Kahlo, and other belatedly-celebrated women painters. —SMS

Absolution by Jeff VanderMeer [F]

What it is: A surprise return to the Area X, the stretch of unforbidding and uncanny coastline in the hit Southern Reach trilogy.

Who it's for: Anyone who's heard this song and got the reference without Googling it. —JHM

The Four Horsemen by Nick Curtola [NF]

What it is: The much-anticipated cookbook from the team behind Brooklyn's hottest restaurant (which also happens to be co-owned by James Murphy of LCD Soundsystem).

Who it's for: Oenophiles; thirty-somethings who live in north Williamsburg (derogatory). —SMS

Seeing Further by Esther Kinsky, tr. Caroline Schmidt [F]

What it's about: An unnamed German woman embarks on the colossal task of reviving a cinema in a small Hungarian village.

Who it's for: Fans of Jenny Erpenbeck; anyone charmed by Cinema Paradiso (not derogatory!). —SMS

Ripcord by Nate Lippens [NF]

What it's about: A novel of class, sex, friendship, and queer intimacy, written in delicious prose and narrated by a gay man adrift in Milwaukee.

Who it's for: Fans of Brontez Purnell, Garth Greenwell, Alexander Chee, and Wayne Koestenbaum. —SMS

The Use of Photography by Annie Ernaux and Marc Marie, tr. Alison L. Strayer [NF]

What it's about: Ernaux's love affair with Marie, a journalist, while she was undergoing treatment for cancer, and their joint project to document their romance.

Who it's for: The Ernaux hive, obviously; readers of Sontag's On Photography and Janet Malcolm's Still Pictures. —SMS

Nora Ephron at the Movies by Ilana Kaplan [NF]

What it is: Kaplan revisits Nora Ephron's cinematic watersheds—Silkwood, Heartburn, When Harry Met Sally, You've Got Mail, and Sleepless in Seattle—in this illustrated book. Have these iconic stories, and Ephron’s humor, weathered more than 40 years?

Who it’s for: Film history buffs who don’t mind a heteronormative HEA; listeners of the Hot and Bothered podcast; your coastal grandma. —NodB

[millions_email]

The Philosophy of Translation by Damion Searls [NF]

What it is: A meditation on the act and art of translation by one of today's most acclaimed practitioners, best known for his translations of Fosse, Proust, et al.

Who it's for: Regular readers of Words Without Borders and Asymptote; professional and amateur literary translators alike. —SMS

Salvage by Dionne Brand

What it is: A penetrating reevaluation of the British literary canon and the tropes once shaped Brand's reading life and sense of self—and Brand’s first major work of nonfiction since her landmark A Map to the Door of No Return.

Who it's for: Readers of Christina Sharpe's Ordinary Notes and Elizabeth Hardwick's Seduction and Betrayal. —SMS

Masquerade by Mike Fu [F]

What it's about: Housesitting for an artist friend in present-day New York, Meadow Liu stumbles on a novel whose author shares his name—the first of many strange, haunting happenings that lead up to the mysterious disappearance of Meadow's friend.

Who it's for: fans of Ed Park and Alexander Chee. —SMS

November

The Beggar Student by Osamu Dazai, tr. Sam Bett [F]

What it is: A novella in the moody vein of Dazai’s acclaimed No Longer Human, following the 30-something “fictional” Dazai into another misadventure spawned from a hubristic spat with a high schooler.

Who it's for: Longtime readers of Dazai, or new fans who discovered the midcentury Japanese novelist via TikTok and the Bungo Stray Dogs anime. —DF

In Thrall by Jane DeLynn [F]

What it is: A landmark lesbian bildungsroman about 16-year-old Lynn's love affair with her English teacher, originally published in 1982.

Who it's for: Fans of Joanna Russ's On Strike Against God and Edmund White's A Boy's Own Story —SMS

Washita Love Child by Douglas Kent Miller [NF]

What it is: The story of Jesse Ed Davis, the Indigenous musician who became on of the most sought after guitarists of the late '60s and '70s, playing alongside B.B. King, Bob Dylan, John Lennon, and more.

Who it's for: readers of music history and/or Indigenous history; fans of Joy Harjo, who wrote the foreword. —SMS

Set My Heart on Fire by Izumi Suzuki, tr. Helen O'Horan [F]

What it is: Gritty, sexy, and wholly rock ’n’ roll, Suzuki’s first novel translated into English (following her story collection, Hit Parade of Tears) follows 20-year-old Izumi navigating life, love, and music in the underground scene in '70s Japan.

Who it's for: Fans of Meiko Kawakami, Ursula K. Le Guin, and Marlowe Granados's Happy Hour. —DF

Didion & Babitz by Lili Anolik [NF]

What it is: A dual portrait of Joan Didion and Eve Babitz, who are so often compared to—and pitted against—each other on the basis of their mutual Los Angeles milieu.

Who it's for: Fans or haters of either writer (the book is fairly pro-Babitz, often at Didion's expense); anyone who has the Lit Hub Didion tote bag. —SMS

The Endless Refrain by David Rowell [NF]

What it's about: How the rise of music streaming, demonitizing of artist revenue, and industry tendency toward nostalgia have laid waste to the musical landscape, and the future of music culture.

Who it's for: Fans of Kyle Chayka, Spence Kornhaber, and Lindsay Zoladz. —SMS

Every Arc Bends Its Radian by Sergio De La Pava [F]

What it is: A mind- and genre-bending detective story set in Cali, Colombia, that blends high-stakes suspense with rigorous philosophy.

Who it's for: Readers of Raymond Chandler, Thomas Pynchon, and Jules Verne. —SMS

Something Close to Nothing by Tom Pyun [F]

What it’s about: At the airport with his white husband Jared, awaiting a flight to Cambodia to meet the surrogate mother carrying their adoptive child-to-be, Korean American Wynn decides parenthood isn't for him, and bad behavior ensues.

Who it’s for: Pyun’s debut is calculated to cut through saccharine depictions of queer parenthood—could pair well with Torrey Peters’s Detransition, Baby. —NodB

Rosenfeld by Maya Kessler [F]

What it is: Kessler's debut—rated R for Rosenfeld—follows one Noa Simmons through the tumultuous and ultimately profound power play that is courting (and having a lot of sex with) the titular older man who soon becomes her boss.

Who it's for: Fans of Sex and the City, Raven Leilani’s Luster, and Coco Mellor’s Cleopatra and Frankenstein. —DF

Lazarus Man by Richard Price [F]

What it is: The former The Wire writer offers yet another astute chronicle of urban life, this time of an ever-changing Harlem.

Who it's for: Fans of Colson Whitehead's Crook Manifesto and Paul Murray's The Bee Sting—and, of course, The Wire. —SMS

Stranger Than Fiction by Edwin Frank [NF]

What it is: An astute curveball of a read on the development and many manifestations of the novel throughout the tumultuous 20th century.

Who it's for: Readers who look at a book's colophon before its title. —JHM

Letters to His Neighbor by Marcel Proust, tr. Lydia Davis

What it is: A collection of Proust’s tormented—and frequently hilarious—letters to his noisy neighbor which, in a diligent translation from Davis, stand the test of time.

Who it's for: Proust lovers; people who live below heavy-steppers. —DF

Context Collapse by Ryan Ruby [NF]

What it is: A self-proclaimed "poem containing a history of poetry," from ancient Greece to the Iowa Workshop, from your favorite literary critic's favorite literary critic.

Who it's for: Anyone who read and admired Ruby's titanic 2022 essay on The Waste Land; lovers of poetry looking for a challenge. —SMS

How Sondheim Can Change Your Life by Richard Schoch [NF]

What it's about: Drama professor Schoch's tribute to Stephen Sondheim and the life lessons to be gleaned from his music.

Who it's for: Sondheim heads, former theater kids, end of list. —SMS

The Serviceberry by Robin Wall Kimmerer [NF]

What it is: 2022 MacArthur fellow and botanist Kimmerer, an enrolled member of the Citizen Potawatomi Nation, (re)introduces audiences to a flowering, fruiting native plant beloved of foragers and gardeners.

Who it’s for: The restoration ecologist in your life, along with anyone who loved Braiding Sweetgrass and needs a nature-themed holiday gift. —NodB

My Heart Belongs in an Empty Big Mac Container Buried Beneath the Ocean Floor by Homeless [F]

What it is: A pseudonymous, tenderly comic novel of blue whales and Golden Arches, mental illness and recovery.

Who it's for: Anyone who finds Thomas Pynchon a bit too staid. —JHM

Yoke and Feather by Jessie van Eerden [NF]

What it's about: Van Eerden's braided essays explore the "everyday sacred" to tease out connections between ancient myth and contemporary life.

Who it's for: Readers of Courtney Zoffness's Spilt Milk and Jeanna Kadlec's Heretic. —SMS

Camp Jeff by Tova Reich [F]

What it's about: A "reeducation" center for sex pests in the Catskills, founded by one Jeffery Epstein (no, not that one), where the dual phenomena of #MeToo and therapyspeak collide.

Who it's for: Fans of Philip Roth and Nathan Englander; cancel culture skeptics. —SMS

Selected Amazon Reviews by Kevin Killian [NF]

What it is: A collection of 16 years of Killian’s funniest, wittiest, and most poetic Amazon reviews, the sheer number of which helped him earn the rarefied “Top 100” and “Hall of Fame” status on the site.

Who it's for: Fans of Wayne Koestenbaum and Dodie Bellamy, who wrote introduction and afterword, respectively; people who actually leave Amazon reviews. —DF

Cher by Cher [NF]

What it is: The first in a two-volume memoir, telling the story of Cher's early life and ascendent career as only she can tell it.

Who it's for: Anyone looking to fill the My Name Is Barbra–sized hole in their heart, or looking for something to tide them over until the Liza memoir drops. —SMS

The City and Its Uncertain Walls by Haruki Murakami, tr. Philip Gabriel [F]

What it is: Murakami’s first novel in over six years returns to the high-walled city from his 1985 story "Hard-Boiled Wonderland and the End of the World" with one man's search for his lost love—and, simultaneously, an ode to libraries and literature itself.

Who it's for: Murakami fans who have long awaited his return to fiction. —DF

American Bulk by Emily Mester [NF]

What it's about: Reflecting on what it means to "live life to the fullest," Mester explores the cultural and personal impacts of America’s culture of overconsumption, from Costco hauls to hoarding to diet culture—oh my!

Who it's for: Lovers of sustainability; haters of excess; skeptics of the title essay of Becca Rothfeld's All Things Are Too Small. —DF

The Icon and the Idealist by Stephanie Gorton [NF]

What it is: A compelling look at the rivalry between Margaret Sanger, of Planned Parenthood fame, and Mary Ware Dennett, who each held radically different visions for the future of birth control.

Who it's for: Readers of Amy Sohn's The Man Who Hated Women and Katherine Turk's The Women of NOW; anyone interested in the history of reproductive rights. —SMS

December

Rental House by Weike Wang [F]

What it's about: Married college sweethearts invite their drastically different families on a Cape Code vacation, raising questions about marriage, intimacy, and kinship.

Who it's for: Fans of Wang's trademark wit and sly humor (see: Joan Is Okay and Chemistry); anyone with an in-law problem.

Woo Woo by Ella Baxter [F]

What it's about: A neurotic conceptual artist loses her shit in the months leading up to an exhibition that she hopes will be her big breakout, poking fun at the tropes of the "art monster" and the "woman of the verge" in one fell, stylish swoop.

Who it's for: Readers of Sheena Patel's I'm a Fan and Chris Kraus's I Love Dick; any woman who is grateful to but now also sort of begrudges Jenny Offil for introducing "art monster" into the lexicon (me). —SMS

Berlin Atomized by Julia Kornberg, tr. Jack Rockwell and Julia Kornberg [F]

What it's about: Spanning 2001 to 2034, three Jewish and downwardly mobile siblings come of age in various corners of the world against the backdrop of global crisis.

Who it's for: Fans of Catherine Lacey's Biography of X and Joshua Cohen's The Netanyahus. —SMS

Sand-Catcher by Omar Khalifah, tr. Barbara Romaine [F]

What it is: A suspenseful, dark satire of memory and nation, in which four young Palestinian journalists at a Jordanian newspaper are assigned to interview an elderly witness to the Nakba, the violent 1948 expulsion of native Palestinians from Israel—but to their surprise, the survivor doesn’t want to rehash his trauma for the media.

Who it’s for: Anyone looking insight—tinged with grim humor—into the years leading up to the present political crisis in the Middle East and the decades-long goal of Palestinian autonomy. —NodB

The Shutouts by Gabrielle Korn [F]

What it's about: In the dystopian future, mysteriously connected women fight to survive on the margins of society amid worsening climate collapse.

Who it's for: Fans of Korn's Yours for the Taking, which takes place in the same universe; readers of Becky Chambers and queer-inflected sci-fi. —SMS

What in Me Is Dark by Orlando Reade [NF]

What it's about: The enduring, evolving influence of Milton's Paradise Lost on political history—and particularly on the work of 12 revolutionary readers, including Malcom X and Hannah Arendt.

Who it's for: English majors and fans of Ryan Ruby and Sarah Bakewell—but I repeat myself. —SMS

The Afterlife Is Letting Go by Brandon Shimoda [NF]

What it's about: Shimoda researches the mass incarceration of Japanese Americans during WWII, and speaks with descendants of those imprisoned, for this essay collection about the “afterlife” of cruelty and xenophobia in the U.S.

Who it’s for: Anyone to ever visit a monument, museum, or designated site of hallowed ground where traumatic events have taken place. —NodB

No Place to Bury the Dead by Karina Sainz Borgo, tr. Elizabeth Bryer [F]

What it's about: When Angustias Romero loses both her children while fleeing a mysterious disease in her unnamed Latin American country, she finds herself in a surreal, purgatorial borderland where she's soon caught in a power struggle.

Who it's for: Fans of Maríana Enriquez and Mohsin Hamid. —SMS

The Rest Is Silence by Augusto Monterroso, tr. Aaron Kerner [F]

What it is: The author of some of the shortest, and tightest, stories in Latin American literature goes long with a metafictional skewering of literary criticism in his only novel.

Who it's for: Anyone who prefers the term "palm-of-the-hand stories" to "flash fiction." —JHM

Tali Girls by Siamak Herawi, tr. Sara Khalili [F]

What it is: An intimate, harrowing, and vital look at the lives of girls and women in an Afghan mountain village under Taliban rule, based on true stories.

Who it's for: Readers of Nadia Hashimi, Akwaeke Emezi, and Maria Stepanova. —SMS

Sun City by Tove Jansson, tr. Thomas Teal [F]

What it's about: During her travels through the U.S. in the 1970s, Jansson became interested in the retirement home as a peculiarly American institution—here, she imagines the tightly knit community within one of them.

Who it's for: Fans of Jansson's other fiction for adults, much of which explores the lives of elderly folks; anyone who watched that documentary about The Villages in Florida. —SMS

Editor's note: We're always looking to make our seasonal book previews more useful to the readers, writers, and critics they're meant to serve. Got an idea for how we can improve our coverage? Tell me about it at sophia@themillions.com.

[millions_email]

Tired of the Same Trump-Era ‘Must-Reads’? Read This Instead

There's a comical number of books we are all supposed to read in this age of Donald Trump. Hannah Arendt’s Origins of Totalitarianism, Sinclair Lewis’s It Can’t Happen Here, Claudia Rankine’s Citizen, and a legion of others that don’t even include all the books about Trump that are written with Trumpian nuance. Books that announce their souls with titles like Fire and Fury and Unhinged. Both sorts—the classics and the classless—risk domination by Trump’s personality. The pervasive, presidential shag has become his own hermeneutic, a maw of interpretation that reduces the loglines for classics and bestsellers alike to his own favorite paradigm: cheap relevancy.

What people need in this fractured age is a book that can accomplish two seemingly contradictory goals. The first is escape, but not your usual escape. By all means, subsume yourself in far-away worlds or cozy cottage deaths; the news shouldn’t play subtext to every waking hour. Additionally, however, is the escape of concentration, an escape that feels especially rare amidst our collective din of notifications. A friend remarked a year or so ago that she found her usual diet of novels more of a tonic than ever because nowhere else could she find as undistracted a mind in action. That perhaps romanticizes the literary experience. Good. We need brighter and more idealistic visions of reading. Concentrate, we should tell ourselves, and thereby feel a little freedom.

The second and more trumpeted goal for reading right now is that we need books that can give us context or insight into what has been (for many of us) a disorienting time. To what extent should we anticipate political dysfunction collapsing into political violence? What factors have contributed to this era of open corruption and rising tribalism, and how do we search for solutions? Here, we are told in various listicles, are books that have answers. And yet there’s one book that is missing from these types of lists, and it isn’t one of the books folks should read, it is the One Book everyone should attempt for 2019. A distraction, a challenge, a historical saga, a spiritual referee, a book so big that back-cover salesmanship and listicle logic shudder under its romping, magisterial shadow. Considered her magnum opus, Rebecca West’s Black Lamb and Grey Falcon is a witty and good-spirited bully, a masterpiece of honest investigation that is as irreducible to the current moment as it is relevant.

Subtitled A Journey Through Yugoslavia, the hulking paperback is often billed as a travelogue. This is technically true, in the same sense that your friend might say, “Meet my cat,” only your friend is a zookeeper. The cat is a lion and perhaps here to eat you. Meet my cat isn’t inaccurate, but neither is it sufficient to explain the situation. Along with her husband and one of Serbia’s leading poets, West tours from Croatia to Montenegro and details an array of pleasant churches, courtyards, sartorial traditions, food, and fertility rites. The book certainly could be used on a journey, or even more likely read as a substitute for one. Its first pleasure is the simplicity of getting away.

But what Black Lamb and Grey Falcon should properly be billed as is an epic of Western history and thought, a book that uses the historical development of the Balkans to investigate nationhood, human violence, spirituality, and the necessity of art. Published in 1941, the post-WWII history of the region does nothing to limit the power of the book’s truths, even when West fails to predict some of the area’s most salient developments (primarily, communism). Never simply one thing, West’s goliath is as interested in the Balkans-qua-Balkans as it is in letting the Balkans’ oppression exemplify humanity’s formal extremes of violence and hate. By formal, I mean the infrastructures that civilizations create to justify, suppress, and foment our basest instincts of annihilation and self-destruction. Caught between the hammer of Austria and the, er, bigger hammer of the Ottoman Empire for most of its history, the Balkans existed in 1937 as a mess of national biases and emergencies. Victims in recovery (one might say), the various nations that composed interwar Yugoslavia indicted at every level the great powers that wrecked them and the spirit behind those powers that wrecked Europe and the world only a few years later. Meet Black Lamb and Grey Falcon; it’s a travelogue.

A definitive hatchet job on the values of imperialism, the book unpacks empire’s fundamental lust for erasure on the part of the aggressor by reviewing three main narratives of history, all of which cover decades of struggle and strife. West begins with the assassination of Franz Ferdinand; continues with the 19th-century liberation and subsequent struggles of Serbia, which climax with the assassinations of King Alexander Obrenovic and his wife Draga; and concludes with the medieval fracturing of the Serbian empire, which lost the ability to self-govern when the Ottomans beat Tsar Lazar soundly in 1389 on the Kosovo field. Duck if West turns your direction, though, because the too-ready concession to pacifism and purity virtue-signaling on the part of those who might oppose the aggressor is also lambasted. At times she sounds like segments of the current American left when it comes to her progressive pals: “Democrats don’t want to rule,” she might tweet, though only as the final punch-line to a thousand-post thread on the evils of American border camps.

If you want relevancy, then Black Lamb and Grey Falcon is as interested in fascism, the exploited urban poor, the rural disaffected, and the malignant stupidity of the powers-that-be as any book I’ve ever read. It features a horrifying travel companion named Gerda, who if represented even half accurately, is a legitimate approximation for the plain-faced bigotry of Nazi Germany that was so explicit as to be easily doubted. West and her husband discuss, in fact, how no one will believe that Gerda could be so anti-Semitic (she’s married to a Jew!) or anti-Slavic (her Jewish husband is a Serbian!). It’s the banality of evil, in a certain sense, long before Arendt made the term famous. Daily life is full of dullness, and when the exceptional occurs, the dullness is often too established to be disrupted. Gerda couldn’t be that bad, part of us thinks, life is never so bald day-to-day. But for all the complications of history, West assures us that we’re wrong. Gerda’s type of hatred is what makes domination thrum. West ultimately pits imperialism against nationalism, insisting that the horrors of the former not be blindly attributed to the latter. Perhaps nationalism as a concept is beyond recovery for you; read this book and discover whether that remains a viable opinion in the face of cultures who must assert their personality as a bulwark against destruction.

So, the book’s content feels current. Yet Black Lamb and Grey Falcon is that much rarer breed, a book of big ideas whose relevancy can’t be draped over whatever fad or crisis is at hand. There are too many facts for such loose abstraction, facts giving birth to other facts at the rate of rabbits. Facts that cast shadows over other facts that all collude to blot out your easy opinions. There are enough facts you wonder if you ever attended a history course or know anything beyond the timeline of your own small life. West opens the book with a reminiscence on the Habsburgs and the Austro-Hungarian Empire, including an account of Empress Elisabeth's 1898 assassination. Her son either killed himself or was assassinated some years before. Why does this matter? It put Franz Ferdinand in line to the throne, which might not have mattered if Alexander Obrenovic and his wife Draga—King and Queen of Serbia (remember?)—hadn't also been assassinated, giving Serbia over to King Peter, who was a capable and intimidating leader. His rehabilitation of Serbia was feared by Austria, but especially by the blustery, hapless, and somewhat pitiable (only because he died) Franz Ferdinand. Hence why he was on the Serbian border when he was shot, which itself was only accomplished by a comedy of errors pulled directly from the imagination of Armando Ianucci.

The too-muchness of all the facts is the point of the book. In some ways, it’s a tracing of causality so complete that you realize the branching effects of any vital action become opaque in their relationship to each other. Trying to hold the accidents of history in your mind in such a way that their connections and disconnections are plain is an exercise in humility and perspective. West wants the reader to know the particulars, but not so that we can pretend to exhaustive comprehension. She wants to share how much she knows precisely because the facts overwhelm even as they illuminate.

Whatever headlines currently dominate your screens, Black Lamb and Grey Falcon transitions from the metaphysical to the historical to the personal with such grace, but also with such relentlessness, that it demands submission. The book is an uncompromising document of hard-won thought and artful intransigence, one that takes you by the hand and teaches you how to read it. History, I could hear West saying, is shorter than you think, and not neutral. Such guidance is the strength of all masterpieces, I think. They teach us a new way of reading that, if we're lucky and receptive and not (you know) evil or anything, inaugurates a new way of seeing the world. I’ve never doubted that something like the Civil War was a cornerstone of American strife, but it was only as I was reading Black Lamb and Grey Falcon that such history felt recent.

While many books attempt to compress the world’s timeline, few, if any, can hope to imitate the way West walks events down a ladder of meaning from the continental to the personal. A perfect moment in one of the historical passages about King Stefan Dusan makes this plain:

In the 49th year of his life, at a village so obscure that it is not now to be identified, he died, in great pain, as if he had been poisoned. Because of his death many disagreeable things happened. For example, we sat in Pristina, our elbows on a tablecloth stained brown and puce, with chicken drumsticks on our plates meagre as sparrow-bones, and there came towards us a man and a woman; and the woman was carrying on her back the better part of a plough.

Comic rather than profound, the movement in this excerpt is a microcosm of the book’s audacity. A king dying in the 14th century in a country distant from her own cannot be impersonal to West if that king’s death not only (in some labyrinth of causality) precipitated the First World War but explains the looming Second World War. Geoffrey Dyer rightly identifies the genius of this passage—and the book—as one of tone. West (the narrator, at least) doesn’t distinguish between persons living or dead, events grand or minimal. They all act upon her, and she unravels their knotted connections with unerring wit.

Perhaps West makes her own case best: “Art is not a plaything, but a necessity, and its essence, form, is not decorative adjustment, but a cup into which life can be poured and lifted to the lips and be tested.” A goblet, a shot, a canteen—a quaff is more than the liquid. A pint of whiskey is still whiskey, but also a cry for help. West’s form is irreducible to scale, although the book’s length makes demands of the reader in and of itself. Her conversations with her husband, her friends, the locals; her forays into art history and craft categorization; her boundless self-deprecation; her insistence that history be viewed intact, every point of the present roped and knotted to leashes reaching out from the past; it’s a grandiose and ridiculous project held together by her casual intimacy with narratives small, epic, and middle-class.

The book is Platonic dialogue, political intrigue, spiritual memoir, vicarious tourism, and not least a polemical tirade aimed at Ancient Rome, Neville Chamberlain, and any idiot in-between. The political history and philosophy the book details are vital, but I can’t think of any other text I’ve either read or even read about that elevates journalism to Homeric proportions. Black Lamb and Grey Falcon is an argument that news cycles last hundreds of years. Our own moment will pass, but its consequences will remain recent history long after we’re dead. Read anyone else you please in the Year of Our Lord 2019, but Rebecca West is relevance immortalized.

Image: Flickr/Jo Naylor

Most Anticipated: The Great First-Half 2019 Book Preview

As you learned last week, The Millions is entering into a new, wonderful epoch, a transition that means fretting over the Preview is no longer my purview. This is one of the things I’ll miss about editing The Millions: it has been a true, somewhat mind-boggling privilege to have an early look at what’s on the horizon for literature. But it’s also a tremendous relief. The worst thing about the Preview is that a list can never be comprehensive—we always miss something, one of the reasons that we established the monthly previews, which will continue—and as a writer I know that lists are hell, a font of anxiety and sorrow for other writers.

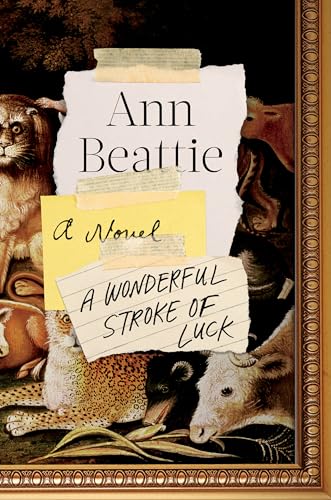

That said, the technical term for this particular January-through-June list is Huge Giant Monster. Clocking in at more than 120 books, it is quite simply, too long. (If I were still the editor and he were still the publisher, beloved site founder C. Max Magee would be absolutely furious with me.) But this over-abundance means blessings for all of us as readers. The first half of 2019 brings new books from Millions contributing editor Chigozie Obioma, and luminaries like Helen Oyeyemi, Sam Lipsyte, Marlon James, Yiyun Li, and Ann Beattie. There are mesmerizing debuts. Searing works of memoir and essay. There’s even a new book of English usage, fodder for your future fights about punctuation.

Let’s celebrate very good things, and a lot of them, where we find them. The Millions, its writers, and its readers have been some of my very good things. I’m so grateful for the time I’ve spent as editor, and with all of you. Happy new year, and happy reading. I'll be seeing you around.

-Lydia Kiesling

January

An Orchestra of Minorities by Chigozie Obioma: Millions Contributing Editor Obioma’s debut novel, The Fishermen, is a merciless beauty and one of my favorites of 2015. I wasn’t alone in this feeling: The Fishermen garnered universal critical acclaim with its recasting of biblical and African mythos to create a modern Nigerian tragedy. His second novel, An Orchestra of Minorities, is a contemporary retelling of Homer’s Odyssey blended with Igbo folklore that has received similar glowing notice so far. As Booklist says in a starred review, An Orchesta of Minorities is “magnificently multilayered…Obioma's sophomore title proves to be an Odyssean achievement.” (Adam P.)

Hark by Sam Lipsyte: In Lipsyte’s latest novel since The Ask, we meet Hark Morner, an accidental guru whose philosophies are a mix of mindfulness, fake history, and something called “mental archery.” Fellow comedic genius Paul Beatty calls it “wonderfully moving and beautifully musical.” While Kirkus thought it too sour and misanthropic, Publishers Weekly deemed it “a searing exploration of desperate hopes.” Their reviewer adds, “Lipsyte’s potent blend of spot-on satire, menacing bit players, and deadpan humor will delight readers.” (Edan)

Mouthful of Birds by Samanta Schweblin: Schweblin’s Fever Dream, published in America in 2017 and shortlisted for the Booker Prize, was, excepting Fire and Fury, perhaps the most frightening book of the last two years. Schweblin has a special knack for blending reality and eerie unreality, and she provides readers more nightmare fuel with Mouthful of Birds, a collection of 20 short stories that has drawn advance praise describing it as “surreal,” “visceral,” “addictive,” and “disturbing.” If you like to be unsettled, settle in. (Adam P.)

We Cast a Shadow by Maurice Carlos Ruffin: VQR columnist and essayist Ruffin now publishes his debut novel, a near-futurist social satire about people in a southern city undergoing "whitening" treatments to survive in a society governed by white supremacy. In a starred review, Publishers Weekly calls this a "singular and unforgettable work of political art.” For Ruffin’s nonfiction, read his excellent essay on gentrification and food in New Orleans for Southern Foodways or his work for VQR. (Lydia)

Late in the Day by Tessa Hadley: It took Hadley 46 years to publish her first novel, 2002’s Accidents in the Home. In the 17 years since, she has made up for lost time, publishing three story collections and six novels, including Late in the Day, about two middle-aged married couples coping with the death of one member of their tight-knit quartet. “Hadley is a writer of the first order,” says Publishers Weekly, “and this novel gives her the opportunity to explore, with profound incisiveness and depth, the inevitable changes inherent to long-lasting marriages.” (Michael)

House of Stone by Novuyo Rosa Tshuma: House of Stone is a debut novel by Zimbabwean author Tshuma. The book opens with the narrative of a 24-year-old tenant Zamani, who works to make his landlord and landlady love him more than they loved their son, Bukhosi, who went missing during a protest in Bulawayo, Zimbabwe. In his book review for The Guardian, Helon Habila praises Tshuma as a "wily writer," and says that her book is full of surprises. House of Stone not only takes unexpected turns in terms of plot lines, but also bears no single boring sentence. It makes the violent political scenes and circumstance-driven characters vivid on the page and thus renders Zimbabwean history in a very powerful and yet believable way. (Jianan)

Sugar Run by Mesha Maren: In what Publishers Weekly describes as an “impressive debut replete with luminous prose,” Maren’s Sugar Run tells the story of Jodi McCarty, unexpectedly released from prison after 18 years inside. McCarty meets and quickly falls in love with Miranda, a troubled young mother, and together they set out towards what they hope will be a better life. Set within the insular confines of rural West Virginia, Sugar Run is a searing, gritty novel about escape—the longing for it, the impossibility of it—and it announces Maren as a formidable talent to watch. (Adam P.)

The Far Field by Madhuri Vijay: Searching for answers about her late mother, Shalini, a 30-year-old privileged woman, travels from Bangalore to Kashmir in search of a mysterious man from her past. In the remote village, political and military tensions rise and threaten the new community she’s immersed herself in. Publishers Weekly, in starred review, wrote: “Vijay’s stunning debut novel expertly intertwines the personal and political to pick apart the history of Jammu and Kashmir.” (Carolyn)

Thick by Tressie McMillan Cottom: A scholar who has earned acclaim both within her discipline of Sociology and outside of the academy for her book Lower Ed, on the predatory for-profit college industry, Cottom has a huge following that looks to her for her trenchant analyses of American society. Now she publishes a collection of essays on race, gender, money, work, and class that combines scholarship and lived experience with Cottom's characteristic rigor and style. (Lydia)

To Keep the Sun Alive by Rebeah Ghaffari: A story of the family of a retired judge in Iran just before the Revolution, where the events that roil the family are set against, and affected by, the events that will roil the nation. Kirkus calls this "an evocative and deeply felt narrative portrait." (Lydia)

Castle on the River Vistula by Michelle Tea: Protagonist Sophie Swankowski’s journeys in Tea’s Young Adult Chelsea Trilogy will come to an end in Castle on the River Vistula, when the 13-year-old magician journeys from her home in Massachusetts to Poland, the birthplace of her friend “the gruff, filthy mermaid Syrena.” Tea is an author familiar with magic, having penned Modern Tarot: Connecting with Your Higher Self through the Wisdom of the Cards, and she promises to bring a similar sense of the supernatural in Sophie’s concluding adventures. (Ed)

Mothers by Chris Power: Smooth and direct prose makes Power’s debut story collection an entrancing read. In “Portals,” the narrator meets Monica, a dancer from Spain, and her boyfriend. “We drank a lot and told stories.” A year later, Monica messages the narrator and says she wants to meet up—and is newly single. Power pushes through the narration, as if we have been confidently shuffled into a room to capture the most illuminating moments of a relationship. Lying on the grass together, Monica stares at the narrator as she rolls onto her back. “It was an invitation, but I hesitated. This was exactly what I had come for, but now the tiny space between us felt unbridgeable.” Mothers is full of those sharp moments of our lives: the pulse of joy, the sting of regret. (Nick R.)

Nobody’s Looking At You by Janet Malcolm: This essay collection is a worthy follow-up to Malcolm’s Forty-One False Starts, which was a finalist for the National Book Critics Circle Award for Criticism. In this new collection, readers can catch up on the masterful profiles of Eileen Fisher, Rachel Maddow, and Yuju Wang they may have missed in The New Yorker, as well as book reviews and literary criticism. (Hannah)

Talent by Juliet Lapidos: This debut is a literary mystery/campus novel set into motion by a graduate student, Anna Brisker, who can’t finish her dissertation on “an intellectual history of inspiration.” When Anna crosses paths with the niece of a deceased writer famous for his writer’s block, she’s thrilled to discover that the eminent writer has left behind unfinished work. Anna thinks she’s found the perfect case study for her thesis, but soon learns that the niece’s motives aren’t what they seem and that the author’s papers aren’t so easily interpreted. (Hannah)

Golden State by Ben Winters: With The Last Policemen Trilogy and Underground Airlines, Winters has made a career of blending speculative fiction with detective noir. His next in that vein is Golden State, a novel set in California in the not-too-distant future—an independent state where untruth is the greatest offense. Laszlo Ratesic works as a Speculator, a state force with special abilities to sense lies. (Janet)

Hear Our Defeats by Laurent Gaudé: Prix Goncourt winning French playwright Gaudé’s philosophical meditation on human foibles and violence makes its English language debut. Bracketed around the romance of a French intelligence officer and an Iraqi archeologist, the former in pursuit of an American narco-trafficker and the latter attempting to preserve sites from ISIS, Hear Our Defeats ultimately ranges across history, including interludes from Ulysses S. Grant pushing into Virginia and Hannibal’s invasion of Rome. (Ed)

You Know You Want This by Kristen Roupenian: The short story collection whose centerpiece is "Cat Person," the viral sensation that had millions of people identifying with/fearing/decrying/loving/debating a work of short fiction last year. (Lydia)

Last Night in Nuuk by Niviaq Korneliussen: This writer from Greenland was 22 when she won a prestigious writing prize, and her subsequent debut novel took the country by storm. Now available for U.S. readers, a profile in The New Yorker calls the novel "a work of a strikingly modern sensibility—a stream-of-consciousness story of five queer protagonists confronting their identities in twenty-first-century Greenlandic culture." (Lydia)

Dreyer's English by Benjamin Dreyer: A guide to usage by a long-time Random House copyeditor that seems destined to become a classic (please don’t copyedit this sentence). George Saunders calls it "A mind-blower—sure to jumpstart any writing project, just by exposing you, the writer, to Dreyer’s astonishing level of sentence-awareness.” (Lydia)

February

Black Leopard, Red Wolf by Marlon James: Following up his Man Booker Prize for A Brief History of Seven Killings, James has written the first book in what is to be an epic trilogy that is part Lord of the Rings, part Game of Thrones, and part Black Panther. In this first volume, a band of mercenaries—made up of a witch, a giant, a buffalo, a shape-shifter, and a bounty hunter who can track anyone by smell (his name is Tracker)—are hired to find a boy, missing for three years, who holds special interest for the king. (Janet)

Where Reasons End by Yiyun Li: Where Reasons End is the latest novel by the critically acclaimed author of Dear Friend, from My Life I Write to You in Your Life. Li creates this fictional space where a mother can have an eternal, carefree conversation with her child Nikolai, who commits suicide at the age of 16. Suffused with intimacy and deepest sorrows, the book captures the affections and complexity of parenthood in a way that has never been portrayed before. (Jianan)

The Collected Schizophrenias by Esmé Weijun Wang: Wang writes brilliantly and beautifully about lives lived with mental illness. Her first novel, The Border of Paradise, traces a family through generations, revealing the ways each becomes inheritors of the previous generation’s isolation and depression. In The Collected Schizophrenias, her first essay collection (for which she was awarded the Whiting Award and Greywolf Nonfiction Prize), Wang draws from her experience as both patient and speaker/advocate navigating the vagaries of the mental healthcare system while also shedding light on the ways it robs patients of autonomy. What’s most astonishing is how Wang writes with such intelligence, insight, and care about her own struggle to remain functional while living with schizoaffective disorder. (Anne)

American Spy by Lauren Wilkinson: It’s the mid-1980s and American Cold War adventurism has set its sights on the emerging west African republic of Burkina Faso. There’s only one problem: the agent sent to help swing things America’s way is having second, and third, thoughts. The result is an engaging and intelligent stew of espionage and post-colonial political agency, but more important, a confessional account examining our baser selves and our unscratchable itch to fight wars that cannot be won. (Il’ja)

Lost Children Archive by Valeria Luiselli: The two-time

finalist for the National Book Critic’s Circle Award has written a road novel

for America in the 21st century. In the book, a family of four set out from their home in New York to visit a place in Arizona called Apacheria, a.k.a. the region once inhabited by the Apache tribe. On their way down south, the family reveals their own set of long-simmering conflicts, while the radio gives updates on an “immigration crisis” at the border. (Thom)

The White Book by Han Kang (translated by Deborah Smith): In 2016, Kang’s stunning

novel The Vegetarian won the Man Booker Prize; in 2018, she drew Man Booker attention again with her autobiographical work The White Book. There are loose connections between the two—both concern sisters, for one, and loss, and both feature Han’s beautiful, spare prose—but The White Book is less a

conventional story and more like a meditation in fragments. Written about and to the narrator’s older sister, who died as a newborn, and about the white objects of grief, Han’s work has been likened to “a secular prayer book,” one that “investigates the fragility, beauty and strangeness of life.” (Kaulie)

Bangkok Wakes to Rainby Pitchaya Sudbanthad: NYFA Fellow Sudbanthad’s debut novel, Bangkok Wakes to Rain, has already been

hailed as “important, ambitious, and accomplished,” by Mohsin Hamid, and a book

that “brilliantly sounds the resonant pulse of the city in a wise and far-reaching meditation on home,” by Claire Vaye Watkins. This polyphonic novel follows myriad characters—from a self-exiled jazz pianist to a former student

revolutionary—through the thresholds of Bangkok’s past, present, and future. Sudbanthad, who splits his time between Bangkok and New York, says he wrote the novel by letting his mind wander the city of his birth: “I arrived at the site of a house that, to me, became a theatrical stage where characters…entered and left; I followed them, like a clandestine voyeur, across time and worlds, old and new.” (Anne)

The Source of Self-Regard by Toni Morrison: A new collection of nonfiction--speeches, essays, criticism, and reflections--from the Nobel-prize winning Morrison. Publishers Weekly says ""Some superb pieces headline this rich collection...Prescient and highly relevant to the present political moment..." (Lydia)

Spirit of Science Fiction by Roberto Bolano: Spirit of Science Fiction is a novel by the critically acclaimed author of 2666, Bolano, translated by Natasha Wimmer. Apparently it is a tale about two young poets aspiring to find their positions in the literary world. But the literary world in Bolano’s sense is also a world of revolution, fame, ambition, and more so of sex and love. Like Bolano’s previous fiction, Spirit of Science Fiction is a Byzantine maze of strange and beautiful life adventures that never fails to provide readers with intellectual and emotional satisfaction. (Jianan)

Bowlaway by Elizabeth McCracken: It’s hard to believe it’sbeen 20 years since McCracken published her first novel, The Giant’s House,perhaps because, since then, she’s given us two brilliant short storycollections and one of the most powerful memoirs in recent memory. Her fanswill no doubt rejoice at the arrival of this second novel, which follows threegenerations of a family in a small New England town. Bowlaway refers to acandlestick bowling alley that Publishers Weekly, in its starred review, calls“almost a character, reflecting the vicissitudes of history that determineprosperity or its opposite.” In its own starred review, Kirkus praisesMcCracken’s “psychological acuity.” (Edan)

Good Will Come from the Sea by Christos Ikonomou (translated by Karen Emmerich): In the same way that Greece was supposedly the primogeniture of Western civilization, the modern nation has prefigured over the last decade in much of what defines our current era. Economic hardship, austerity, and the rise of political radicalism are all manifest in the Greece explored by Ikonomou in his short story collection Good Will Come from the Sea. These four interlocked stories explore modern Greece as it exists on the frontlines of both the refugee crisis and scarcity economics. Ikonomou’s stories aren’t about the Greece of chauvinistic nostalgia; as he told an interviewer in 2015 his characters “don’t love the Acropolis; they don’t know what it means,” for it’s superficial “to feel just pride;” rather, the author wishes to “write about the human condition,” and so he does. (Ed)

The Heavens by Sandra Newman: This novel connects analternate universe New York in the year 2000 with Elizabethan England, througha woman who believes she has one foot in each era. A fascinating-soundingromance about art, illness, destiny, and history. In a starred review, Kirkuscalls this "a complex, unmissable work from a writer who deserves wideacclaim." (Lydia)

All My Goodbyes by Mariana Dimópulos (translated by Alice Whitmore): Argentinian writer Dimópulos's first book in English is a novel that focuses on a narrator who has been traveling for a decade. The narrator reflects on her habit of leaving family, countries, and lovers. And when she decides to commit to a relationship, her lover is murdered, adding a haunting and sorrowful quality to her interiority. Julie Buntin writes, “The scattered pieces of her story—each of them wonderfully distinct, laced with insight, violence, and sensuality—cohere into a profound evocation of restlessness, of the sublime and imprisoning act of letting go." (Zoë)

The Hundred Wells of Salaga by Ayesha Harruna Attah: An account of 19th-century Ghana, the novel follows twoyoung girls, Wurche and Aminah, who live in the titular city which is a notoriouscenter preparing people for sale as slaves to Europeans and Americans. Attah’s novelgives a texture and specificity to the anonymous tales of the Middle Passage,with critic Nadifa Mohamad writing in The Guardian that “One of the strengthsof the novel is that it complicates the idea of what ‘African history’ is.”(Ed)

The Age of Light by Whitney Scharer: This much sought-afterdebut, which was the object of a bidding war, is based on the life of LeeMiller, a Vogue model turned photographer who decided she would rather “take apicture than be one.” The novel focuses on Miller’s tumultuous romance withphotographer Man Ray in early 1930s Paris, as Miller made the transition frommuse to artist. Early reviews suggests that the novel more than lives up to itspromise, with readers extolling its complicated heroine and page-turningpacing. (Hannah)

Northern Lights by Raymond Strom: A story about the struggle for survival in a small town in Minnesota, the novel follows the androgynous teen run-away ShaneStephenson who is searching in Holm, Minn., for the mother who abandonedhim. Shane finds belonging among the adrift and addicted of the crumbling town,but he also finds bigotry and hatred. (Ed)

Adèle by Leila Slimani (translated by Sam Taylor): Slimani, who won the Prix Goncourtin 2016, became famous after publishing Dans le jardin de l’ogre, which is nowbeing translated and published in English as Adèle. The French-Morocconnovelist’s debut tells the story of a titular heroine whose burgeoning sexaddiction threatens to ruin her life. Upon winning an award in Morocco for thenovel, Slimani said its primary focus is her character’s “loss of self.” (Thom)

The Nine Cloud Dream by Kim Man-Jung (translated by Heinz Insu Fenkl): Known as "one of the most beloved masterpieces in Korean literature," The Nine Cloud Dream (also known as Kuunmong) takes readers on a journey reminiscent of Dante’s Inferno combining aspects of Buddhism, Taoism, and indigenous Korean shamanic religions in a 17th-century tale, which, rare in Buddhist texts, includes strong representation of women. Accompanied by gorgeous illustrations and an introduction, notations, and translation done by one of my favorite translators, Heinz Insu Fenkl. Akin to Herman Hesse’s Siddhartha, an intriguing read for readers interested in Buddhism, Korea, and mindfulness. (Marie Myung-Ok)

Notes From a Black Woman’s Diary by Kathleen Collins: Notlong after completing her first feature film, Losing Ground, in 1982, Collins died from breast cancer at age 46. In 2017, her short story collectionabout the lives and loves of black Americans in the 1960s, Whatever Happened toInterracial Love?, was published to ringing critical acclaim. Now comes NotesFrom a Black Woman’s Diary, which is much more than the title suggests. Inaddition to autobiographical material, the book includes fiction, plays,excerpts from an unfinished novel, and the screenplay of Losing Ground, withextensive directorial notes. This book is sure to burnish Collins’sflourishing posthumous reputation. (Bill)

Hard to Love by Briallen Hopper: A collection of essays on therelationships between family members and friends, with background on the author’schildhood in an evangelical family. The collection garnered a starredreview from Kirkus and praise from essayist Leslie Jamison, who calls is “extraordinary.”(Lydia)

A Weekend in New York by Benjamin Markovits: Markovits is aversatile writer, his work ranging from a fictional trilogy about Lord Byron toan autobiographical novel about basketball. He returns to athletics in AWeekend in New York, where Paul Essinger is a mid-level tennis player and1,200-1 shot to win the U.S. Open. Essinger may be alone on the court, but he hasplenty of company at his Manhattan home when his parents visit during thetournament. Upon its British publication, The Guardian praised the “light,limber confidence” with which Markowits handles sporting knowledge and hisacute treatment of the family tensions amid “first-world also-rans.” (Matt)

Mother Winter by Sophia Shalmiyev: This debut is the memoirof a young woman’s life shaped by unrelenting existential terror. The story istold in fragmentary vignettes beginning with Shalmiyev’s fraught emigration asa young child from St. Petersburg, Russia to the United States, leaving behindthe mother who had abandoned her. It closes with her resolve to find herestranged mother again. (Il’ja)

Zuleikha by Guzel Yakhina (translated by Lisa C. Hayden): It is 1930 in the Soviet Unionand Josef Stalin’s de-kulakization program has found its pace. Among thevictims is a young Tatar family: the husband murdered, the wife exiled toSiberia. This is her story of survival and eventual triumph. Winner of the 2015Russian Booker prize, this debut novel draws heavily on the first-personaccount of the author’s grandmother, a Gulag survivor. (Il’ja)

The Atlas of Red and Blues by Devi Laskar: This novel'sinciting incident is a police raid on the home the daughter of Bengaliimmigrants, told from her perspective as she lies bleeding and running throughthe events, experiences, and memories that have led her to this moment. KieseLaymon calls Laskar's book "as narratively beautiful as it isbrutal...I’ve never read a novel that does nearly as much in so few pages.Laskar has changed how we will all write about state-sanctioned terror in thisnation.” (Lydia)

Sea Monsters by Chloe Aridjis: Imagine if Malcom Lowry’shallucinogenic masterpiece Under the Volcano, about the drunken perambulationsof a British consul in a provincial Mexican village on Dia de Los Muertos, hadbeen written by a native of that country? Such could describe Aridjis'snovel Sea Monsters, which follows the 17-year-old Luisa and her acquaintanceTomás as they leave Mexico City in search of a troupe of Ukrainian dwarves whohave defected from a Soviet circus. Luisa eventually settles in Oaxaca whereLuisa takes sojourns to the “Beach of the Dead” in search of anyone who “nomatter what” will “remain a mystery.” (Ed)

Elsewhere, Home by Leila Aboulela: The 13 stories inAboulela's new collection are set in locales as distant as Khartoum and London,yet throughout they explore the universal feelings of the migrant experience:displacement, longing, but also the incandescent hope of creating a differentlife. (Nick M.)

The Cassandra by Sharma Shields: Mildred Groves, TheCassandra’s titular prophetess, sometimes sees flashes of the future. She isalso working at the top-secret Hanford Research Center in the 1940s, where theseeds of atomic weapons are sown and where her visions are growing morehorrifying—and going ignored at best, punished at worst. Balancing thoroughresearch and mythic lyricism, Shields’s novel is a timely warning of whathappens when warnings go unheeded. (Kaulie)

Tonic and Balm by Stephanie Allen: A new title from ShadeMountain Press, Tonic and Balm takes place in 1919, it's setting a travelingmedicine show, complete with "sideshows," sword-swallowers, anddubious remedies. The book explores this show's peregrinations against thebackdrop of poverty and racist violence in rural Pennsylvania. Allen's firstbook, A Place Between Stations: Stories, was a finalist for the Hurston-WrightLegacy Award. (Lydia)

Death Is Hard Work by Khaled Khalifa (translated by Leri Price): “Most of my friendshave left the country and are now refugees,” Khalifa wrote in a recentessay. Yet he remains in Syria, a place where “those of us who have stayed aredying one by one, family by family, so much so that the idea of an empty citycould become a reality.” If literature is a momentary stay against confusion,then Khalifa’s novels are ardent stays against destruction and decay—and DeathIs Hard Work continues this tradition. The novel begins with the dying hours ofAbdel Latif al-Salim, who looks his son Bolbol “straight in the eye” in orderto give his dying wish: to be buried several hours away, next to his sister.The novel becomes a frenetic attempt for his sons to honor this wish and reachAnabiya. “It’s only natural for a man,” Khalifa writes, “to be weak and makeimpossible requests.” And yet he shows this is what makes us human. (Nick R.)

Aerialists by Mark Mayer. For those gutted by the news ofRingling Bros. and Barnum & Bailey Circus closing in 2017, Mayer’s debutcollection supplies a revivifying dose of that carney spirit. The storiesfeature circus-inspired characters—most terrifyingly a murderous clown-cum-realestate agent—in surrealist situations. We read about a bearded womanrevolutionist, a TV personality strongwoman, and, in the grand tradition of petburial writing that reached its acme with Evelyn Waugh’s The Loved One, thefuneral of a former circus elephant. Publishers Weekly called it a “high-wiredebut [that] exposes the weirdness of everyday life.” (Matt)

Friend of My Youth by Amit Chaudhuri: Published for thefirst time in the U.S., this is the seventh novel by the renowned writer, awork of autofiction about a novelist named Amit Chaudhuri revisiting hischildhood in Mumbai. Publishers Weekly says, "in this cogent andintrospective novel, Chaudhuri movingly portrays how other people can allowindividuals to connect their present and past." (Lydia)

A People’s Future of the United States edited by Victor LaValle and John Joseph Adams: An anthology of 25 speculative stories from a range of powerful storytellers, among them Maria Dahvana Headley, Daniel José Older, and Alice Sola Kim. LaValle and Adams sought stories that imagine a derailed future—tales that take our fractured present and make the ruptures even further. Editor LaValle, an accomplished speculative fiction writer himself (most recently The Changeling, and my personal favorite, the hilarious and booming Big Machine), is the perfect writer to corral these stories. LaValle has said “one of the great things about horror and speculative fiction is that you are throwing people into really outsized, dramatic situations a lot...[including] racism and sexism and classism, biases against the mentally ill”—the perfect description for this dynamic collection. (Nick R.)

Trump Sky Alpha by Mark Doten: Doten’s Trump Sky Alpha,is the first and last Trump novel I’ll ever want to read. Doten started writingthe novel in 2015, when our current predicament, I mean, president, was a mereand unfathomable possibility. Doten’s President Trump brings about the nuclearapocalypse, and in its aftermath a journalist takes an assignment to researchInternet humor at the end of the world. The result? An “unconventional anddarkly satirical mix of memes, Twitter jokes, Q&As, and tightly writtenstream-of-consciousness passages,” according to Booklist. From this feat, saysJoshua Cohen,“Mark Doten emerges as the shadow president of our benightedgeneration of American literature.” (Anne)

Nothing but the Night by John Williams: The John Williams ofStoner fame revival continues with the reissue of his first novel by NYRB,first published in 1948, a story dealing with mental illness and trauma withechoes of Greek tragedy. (Lydia)

Famous Children and Famished Adults by Evelyn Hampton:“[Evelyn] Hampton’s stunned sentences will remind you, because you haveforgotten, how piercingly disregulating life is,” writes Stacey Levine ofHampton’s debut story collection Discomfort, published by Ellipsis Press. Ifirst encountered Hampton’s fictions through her novella, Madam, a story of aschoolteacher and her pupils at an academy, where memory is a vehicle and somuch seems a metaphor and language seems to turn in on itself. Hampton’sforthcoming story collection Famous Children and Famished Adults won FC2’sRonald Sukenick Innovative Fiction Prize, and continues with the quixotic. Inthis collection, Noy Holland says, “the exotic and toxic intermingle.” (Anne)

March

The Old Drift by Namwali Serpell: Described as the “Great Zambian Novel you didn’t know you were waiting for,” this debut novel, from the winner of the 2015 Caine Prize for African writing, tells the story of three Zambian families—black, white, and brown—caught in a centuries-long cycle of retribution, romance, and political change. Serpell asks, “How do you live a life or forge a politics that can skirt the dual pitfalls of fixity (authoritarianism) and freedom (neoliberalism)? And what happens if you treat error not as something to avoid but as the very basis for human creativity and community?” Recipient of a starred review from Kirkus and advance praise from Carmen Maria Machado, Alice Sebold, and Garth Greenwell, The Old Drift is already well positioned to become the Next Big Thing of 2019. (Jacqueline)

Gingerbread by Helen Oyeyemi: Oyeyemi became a criticaldarling in 2014 with Boy, Snow, Bird, a retelling of "Snow White." She takes usback into fairy tale world with Gingerbread, the story of mother and daughter,Harriet and Perdita Lee, and their family's famous, perhaps...magical,gingerbread recipe. Along with Harriet's childhood friend Gretel, the Leesendure family, work, and money drama all for the sake of that crunchy spice.(Janet)

The Reign of the Kingfisher by TJ Martinson: Martinson’s debut novel is set in a Chicago that used to have a superhero. It’sone of those books that plays with genre in an interesting way: the prologuereads like a graphic novel, and the entire book reads like literary detectivefiction. With a superhero in it. Back in the 1980s, a mysterious and inhumanlystrong man known as the Kingfisher watched over the streets, until hismutilated body was recovered from the river. In his absence, crime once againbegan to rise. But did the Kingfisher really die? Or did he fake his own death?If he faked his own death, why won’t he return to save his city? Either way,the book suggests, we cannot wait for a new superhero, or for the return of theold one. We must save ourselves. (Emily)

Lot by Bryan Washington: Washington is a talentedessayist—his writing on Houston for Catapult and elsewhere are must-reads—andLot is a glowing fiction debut. Imbued with the flesh of fiction, Lot is aliterary song for Houston. “Lockwood,” the first story, begins: “Roberto wasbrown and his people lived next door so of course I went over on weekends. Theywere full Mexican. That made us superior.” Their house was a “shotgun withswollen pipes.” A house “you shook your head at when you drove up the road.”But the narrator is drawn to Roberto, and when they are “huddled in hiscloset,” palms squeezed together, we get the sense Washington has a keen eyeand ear for these moments of desire and drama. His terse sentences punch andpop, and there’s room for our bated breath in the remaining white space. (NickR.)

The New Me by Halle Butler: If Butler’s first novel,Jillian, was the “feel-bad book of the year,” then her second, The New Me, is askewering of the 21st-century American dream of self-betterment. Butlerhas already proven herself a master of writing about work and its discontents,the absurdity of cubicle life and office work in all of its dead ends. The NewMe takes it to a new level in what Catherine Lacey calls a Bernhardian “darkcomedy of female rage." The New Me portrays a 30-year old temp worker whoyearns for self-realization, but when offered a full-time job, she becomesparalyzed realizing the hollowness of its trappings. (Anne)

Kaddish.com by Nathan Englander: Pulitzer finalist Englander’s latest novel follows Larry, an atheist in a family of orthodox MemphisJews. When he refuses to recite the Kaddish, the Jewish prayer for the dead,for his recently deceased father, Larry risks shocking his family andimperiling the fate of his father’s soul. Like everyone else in the21st century, Larry decides the solution lies online, and he makes awebsite, kaddish.com, to hire a stranger to recite the daily prayer in hisplace. What follows is a satirical take on God, family, and the Internet thathas been compared to early Philip Roth. (Jacqueline)