Mentioned in:

The Great Fall 2024 Book Preview

With the arrival of autumn comes a deluge of great books. Here you'll find a sampling of new and forthcoming titles that caught our eye here at The Millions, and that we think might catch yours, too. Some we’ve already perused in galley form; others we’re eager to devour based on their authors, plots, or subject matters. We hope your next fall read is among them.

—Sophia Stewart, editor

October

Season of the Swamp by Yuri Herrera, tr. Lisa Dillman [F]

What it is: An epic, speculative account of the 18 months that Benito Juárez spent in New Orleans in 1853-54, years before he became the first and only Indigenous president of Mexico.

Who it's for: Fans of speculative history; readers who appreciate the magic that swirls around any novel set in New Orleans. —Claire Kirch

The Black Utopians by Aaron Robertson [NF]

What it is: An exploration of Black Americans' pursuit and visions of utopia—both ideological and physical—that spans the Reconstruction era to the present day and combines history, memoir, and reportage.

Who it's for: Fans of Saidiya Hartman's Wayward Lives, Beautiful Experiments and Kristen R. Ghodsee's Everyday Utopia. —Sophia M. Stewart

The Third Realm by Karl Ove Knausgaard, tr. Martin Aitken [F]

What it is: The third installment in Knausgaard's Morning Star series, centered on the appearance of a mysterious new star in the skies above Norway.

Who it's for: Real Knausgaard heads only—The Wolves of Eternity and Morning Star are required reading for this one. —SMS

Brown Women Have Everything by Sayantani Dasgupta [NF]

What it is: Essays on the contradictions and complexities of life as an Indian woman in America, probing everything from hair to family to the joys of travel.

Who it's for: Readers of Durga Chew-Bose, Erika L. Sánchez, and Tajja Isen. —SMS

The Plot Against Native America by Bill Vaughn [F]

What it is: The first narrative history of Native American boarding schools— which aimed "civilize" Indigenous children by violently severing them from their culture— and their enduring, horrifying legacy.

Who it's for: Readers of Ned Blackhawk and Kathleen DuVal. —SMS

The Mighty Red by Louise Erdrich [F]

What it is: Erdrich's latest novel set in North Dakota's Red River Valley is a tale of the intertwined lives of ordinary people striving to survive and even thrive in their rural community, despite environmental upheavals, the 2008 financial crisis, and other obstacles.

Who it's for: Readers of cli-fi; fans of Linda LeGarde Grover and William Faulkner. —CK

The Position of Spoons by Deborah Levy [NF]

What it is: The second book from Levy in as many years, diverging from a recent streak of surrealist fiction with a collection of essays marked by exceptional observance and style.

Who it's for: Close lookers and the perennially curious. —John H. Maher

The Bog Wife by Kay Chronister [F]

What it's about: The Haddesley family has lived on the same West Virginia bog for centuries, making a supernatural bargain with the land—a generational blood sacrifice—in order to do so—until an uncovered secret changes everything.

Who it's for: Readers of Karen Russell and Jeff VanderMeer; anyone who has ever used the phrase "girl moss." —SMS

The Great When by Alan Moore [F]

What it's about: When an 18-year old book reseller comes across a copy of a book that shouldn’t exist, it threatens to upend not just an already post-war-torn London, but reality as we know it.

Who it's for: Anyone looking for a Sherlock Holmes-style mystery dipped in thaumaturgical psychedelia. —Daniella Fishman

The Message by Ta-Nehisi Coates [NF]

What it's about: One of our sharpest critical thinkers on social justice returns to nonfiction, nearly a decade after Between the World and Me, visiting Dakar, to contemplate enslavement and the Middle Passage; Columbia, S.C., as a backdrop for his thoughts on Jim Crow and book bans; and the Israeli-occupied West Bank, where he sees contemporary segregation in the treatment of Palestinians.

Who it’s for: Fans of James Baldwin, George Orwell, and Angela Y. Davis; readers of Nikole Hannah-Jones’s The 1619 Project and Isabel Wilkerson’s Caste, to name just a few engagements with national and racial identity. —Nathalie op de Beeck

Abortion by Jessica Valenti [NF]

What it is: Columnist and memoirist Valenti, who tracks pro-choice advocacy and attacks on the right to choose in her Substack, channels feminist rage into a guide for freedom of choice advocacy.

Who it’s for: Readers of Robin Marty’s The New Handbook for a Post-Roe America, #ShoutYourAbortion proponents, and followers of Jennifer Baumgartner’s [I Had an Abortion] project. —NodB

Gifted by Suzuki Suzumi, tr. Allison Markin Powell [F]

What it's about: A young sex worker in Tokyo's red-light district muses on her life and recounts her abusive mother's final days, in what is Suzuki's first novel to be translated into English.

Who it's for: Readers of Susan Boyt and Mieko Kanai; fans of moody, introspective fiction; anyone with a fraught relationship to their mother. —SMS

Childish Literature by Alejandro Zambra, tr. Megan McDowell [F]

What it is: A wide-ranging collection of stories, essays, and poems that explore childhood, fatherhood, and family.

Who it's for: Fans of dad lit (see: Lucas Mann's Attachments, Keith Gessen's Raising Raffi, Karl Ove Knausgaard's seasons quartet, et al). —SMS

Books Are Made Out of Books ed. Michael Lynn Crews [NF]

What it is: A mining of the archives of the late Cormac McCarthy with a focus on the famously tight-lipped author's literary influences.

Who it's for: Anyone whose commonplace book contains the words "arquebus," "cordillera," or "vinegaroon." —JHM

Slaveroad by John Edgar Wideman [F]

What it is: A blend of memoir, fiction, and history that charts the "slaveroad" that runs through American history, spanning the Atlantic slave trade to the criminal justice system, from the celebrated author of Brothers and Keepers.

Who it's for: Fans of Clint Smith and Ta-Nehisi Coates. —SMS

Linguaphile by Julie Sedivy [NF]

What it's about: Linguist Sedivy reflects on a life spent loving language—its beauty, its mystery, and the essential role it plays in human existence.

Who it's for: Amateur (or professional) linguists; fans of the podcast A Way with Words (me). —SMS

An Image of My Name Enters America by Lucy Ives [NF]

What it is: A collection of interrelated essays that connect moments from Ives's life to larger questions of history, identity, and national fantasy,

Who it's for: Fans of Ives, one of our weirdest and most wondrous living writers—duh; anyone with a passing interest in My Little Pony, Cold War–era musicals, or The Three Body Problem, all of which are mined here for great effect. —SMS

Women's Hotel by Daniel Lavery [F]

What it is: A novel set in 1960s New York City, about the adventures of the residents of a hotel providing housing for young women that is very much evocative of the real-life legendary Barbizon Hotel.

Who it's for: Readers of Mary McCarthy's The Group and Rona Jaffe's The Best of Everything. —CK

The World in Books by Kenneth C. Davis [NF]

What it is: A guide to 52 of the most influential works of nonfiction ever published, spanning works from Plato to Ida B. Wells, bell hooks to Barbara Ehrenreich, and Sun Tzu to Joan Didion.

Who it's for: Lovers of nonfiction looking to cover their canonical bases. —SMS

Blue Light Hours by Bruna Dantas Lobato [F]

What it's about: Through the emanating blue-glow of their computer screens, a mother and daughter, four-thousand miles apart, find solace and loneliness in their nightly Skype chats in this heartstring-pulling debut.

Who it's for: Someone who needs to be reminded to CALL YOUR MOTHER! —DF

Riding Like the Wind by Iris Jamahl Dunkle [NF]

What it is: The biography of Sanora Babb, a contemporary of John Steinbeck's whose field notes and interviews with Dust Bowl migrants Steinbeck relied upon to write The Grapes of Wrath.

Who it's for: Steinbeck fans and haters alike; readers of Kristin Hannah's The Four Winds and the New York Times Overlooked column; anyone interested in learning more about the Dust Bowl migrants who fled to California hoping for a better life. —CK

Innie Shadows by Olivia M. Coetzee [F]

What it is: a work of crime fiction set on the outskirts of Cape Town, where a community marred by violence seeks justice and connection; also the first novel to be translated from Kaaps, a dialect of Afrikaans that was until recently only a spoken language.

Who it's for: fans of sprawling, socioeconomically-attuned crime dramas a la The Wire. —SMS

Dorothy Parker in Hollywood by Gail Crowther [NF]

What it is: A history of the famous wit—and famous New Yorker—in her L.A. era, post–Algonquin Round Table and mid–Red Scare.

Who it's for: Owners of a stack of hopelessly dog-eared Joan Didion paperbacks. —JHM

The Myth of American Idealism by Noam Chomsky and Nathan J. Robinson [NF]

What it is: A potent critique of the ideology behind America's foreign interventions and its status as a global power, and an treatise on how the nation's hubristic pursuit of "spreading democracy" threatens not only the delicate balance of global peace, but the already-declining health of our planet.

Who it's for: Chomskyites; policy wonks and casual critics of American recklessness alike. —DF

Mysticism by Simon Critchley [NF]

What it is: A study of mysticism—defined as an experience, rather than religious practice—by the great British philosopher Critchley, who mines music, poetry, and literature along the way.

Who it's for: Readers of John Gray, Jorge Luis Borges, and Simone Weil. —SMS

Q&A by Adrian Tomine [NF]

What it is: The Japanese American creator of the Optic Nerve comic book series for D&Q, and of many a New Yorker cover, shares his personal history and his creative process in this illustrated unburdening.

Who it’s for: Readers of Tomine’s melancholic, sometimes cringey, and occasionally brutal collections of comics short stories including Summer Blonde, Shortcomings, and Killing and Dying. —NodB

Sonny Boy by Al Pacino [NF]

What it is: Al Pacino's memoir—end of description.

Who it's for: Cinephiles; anyone curious how he's gonna spin fumbling Diane Keaton. —SMS

Seeing Baya by Alice Kaplan [NF]

What it is: The first biography of the enigmatic and largely-forgotten Algerian artist Baya Mahieddine, who first enchanted midcentury Paris as a teenager.

Who it's for: Admirers of Leonora Carrington, Hilma af Klint, Frida Kahlo, and other belatedly-celebrated women painters. —SMS

Absolution by Jeff VanderMeer [F]

What it is: A surprise return to the Area X, the stretch of unforbidding and uncanny coastline in the hit Southern Reach trilogy.

Who it's for: Anyone who's heard this song and got the reference without Googling it. —JHM

The Four Horsemen by Nick Curtola [NF]

What it is: The much-anticipated cookbook from the team behind Brooklyn's hottest restaurant (which also happens to be co-owned by James Murphy of LCD Soundsystem).

Who it's for: Oenophiles; thirty-somethings who live in north Williamsburg (derogatory). —SMS

Seeing Further by Esther Kinsky, tr. Caroline Schmidt [F]

What it's about: An unnamed German woman embarks on the colossal task of reviving a cinema in a small Hungarian village.

Who it's for: Fans of Jenny Erpenbeck; anyone charmed by Cinema Paradiso (not derogatory!). —SMS

Ripcord by Nate Lippens [NF]

What it's about: A novel of class, sex, friendship, and queer intimacy, written in delicious prose and narrated by a gay man adrift in Milwaukee.

Who it's for: Fans of Brontez Purnell, Garth Greenwell, Alexander Chee, and Wayne Koestenbaum. —SMS

The Use of Photography by Annie Ernaux and Marc Marie, tr. Alison L. Strayer [NF]

What it's about: Ernaux's love affair with Marie, a journalist, while she was undergoing treatment for cancer, and their joint project to document their romance.

Who it's for: The Ernaux hive, obviously; readers of Sontag's On Photography and Janet Malcolm's Still Pictures. —SMS

Nora Ephron at the Movies by Ilana Kaplan [NF]

What it is: Kaplan revisits Nora Ephron's cinematic watersheds—Silkwood, Heartburn, When Harry Met Sally, You've Got Mail, and Sleepless in Seattle—in this illustrated book. Have these iconic stories, and Ephron’s humor, weathered more than 40 years?

Who it’s for: Film history buffs who don’t mind a heteronormative HEA; listeners of the Hot and Bothered podcast; your coastal grandma. —NodB

[millions_email]

The Philosophy of Translation by Damion Searls [NF]

What it is: A meditation on the act and art of translation by one of today's most acclaimed practitioners, best known for his translations of Fosse, Proust, et al.

Who it's for: Regular readers of Words Without Borders and Asymptote; professional and amateur literary translators alike. —SMS

Salvage by Dionne Brand

What it is: A penetrating reevaluation of the British literary canon and the tropes once shaped Brand's reading life and sense of self—and Brand’s first major work of nonfiction since her landmark A Map to the Door of No Return.

Who it's for: Readers of Christina Sharpe's Ordinary Notes and Elizabeth Hardwick's Seduction and Betrayal. —SMS

Masquerade by Mike Fu [F]

What it's about: Housesitting for an artist friend in present-day New York, Meadow Liu stumbles on a novel whose author shares his name—the first of many strange, haunting happenings that lead up to the mysterious disappearance of Meadow's friend.

Who it's for: fans of Ed Park and Alexander Chee. —SMS

November

The Beggar Student by Osamu Dazai, tr. Sam Bett [F]

What it is: A novella in the moody vein of Dazai’s acclaimed No Longer Human, following the 30-something “fictional” Dazai into another misadventure spawned from a hubristic spat with a high schooler.

Who it's for: Longtime readers of Dazai, or new fans who discovered the midcentury Japanese novelist via TikTok and the Bungo Stray Dogs anime. —DF

In Thrall by Jane DeLynn [F]

What it is: A landmark lesbian bildungsroman about 16-year-old Lynn's love affair with her English teacher, originally published in 1982.

Who it's for: Fans of Joanna Russ's On Strike Against God and Edmund White's A Boy's Own Story —SMS

Washita Love Child by Douglas Kent Miller [NF]

What it is: The story of Jesse Ed Davis, the Indigenous musician who became on of the most sought after guitarists of the late '60s and '70s, playing alongside B.B. King, Bob Dylan, John Lennon, and more.

Who it's for: readers of music history and/or Indigenous history; fans of Joy Harjo, who wrote the foreword. —SMS

Set My Heart on Fire by Izumi Suzuki, tr. Helen O'Horan [F]

What it is: Gritty, sexy, and wholly rock ’n’ roll, Suzuki’s first novel translated into English (following her story collection, Hit Parade of Tears) follows 20-year-old Izumi navigating life, love, and music in the underground scene in '70s Japan.

Who it's for: Fans of Meiko Kawakami, Ursula K. Le Guin, and Marlowe Granados's Happy Hour. —DF

Didion & Babitz by Lili Anolik [NF]

What it is: A dual portrait of Joan Didion and Eve Babitz, who are so often compared to—and pitted against—each other on the basis of their mutual Los Angeles milieu.

Who it's for: Fans or haters of either writer (the book is fairly pro-Babitz, often at Didion's expense); anyone who has the Lit Hub Didion tote bag. —SMS

The Endless Refrain by David Rowell [NF]

What it's about: How the rise of music streaming, demonitizing of artist revenue, and industry tendency toward nostalgia have laid waste to the musical landscape, and the future of music culture.

Who it's for: Fans of Kyle Chayka, Spence Kornhaber, and Lindsay Zoladz. —SMS

Every Arc Bends Its Radian by Sergio De La Pava [F]

What it is: A mind- and genre-bending detective story set in Cali, Colombia, that blends high-stakes suspense with rigorous philosophy.

Who it's for: Readers of Raymond Chandler, Thomas Pynchon, and Jules Verne. —SMS

Something Close to Nothing by Tom Pyun [F]

What it’s about: At the airport with his white husband Jared, awaiting a flight to Cambodia to meet the surrogate mother carrying their adoptive child-to-be, Korean American Wynn decides parenthood isn't for him, and bad behavior ensues.

Who it’s for: Pyun’s debut is calculated to cut through saccharine depictions of queer parenthood—could pair well with Torrey Peters’s Detransition, Baby. —NodB

Rosenfeld by Maya Kessler [F]

What it is: Kessler's debut—rated R for Rosenfeld—follows one Noa Simmons through the tumultuous and ultimately profound power play that is courting (and having a lot of sex with) the titular older man who soon becomes her boss.

Who it's for: Fans of Sex and the City, Raven Leilani’s Luster, and Coco Mellor’s Cleopatra and Frankenstein. —DF

Lazarus Man by Richard Price [F]

What it is: The former The Wire writer offers yet another astute chronicle of urban life, this time of an ever-changing Harlem.

Who it's for: Fans of Colson Whitehead's Crook Manifesto and Paul Murray's The Bee Sting—and, of course, The Wire. —SMS

Stranger Than Fiction by Edwin Frank [NF]

What it is: An astute curveball of a read on the development and many manifestations of the novel throughout the tumultuous 20th century.

Who it's for: Readers who look at a book's colophon before its title. —JHM

Letters to His Neighbor by Marcel Proust, tr. Lydia Davis

What it is: A collection of Proust’s tormented—and frequently hilarious—letters to his noisy neighbor which, in a diligent translation from Davis, stand the test of time.

Who it's for: Proust lovers; people who live below heavy-steppers. —DF

Context Collapse by Ryan Ruby [NF]

What it is: A self-proclaimed "poem containing a history of poetry," from ancient Greece to the Iowa Workshop, from your favorite literary critic's favorite literary critic.

Who it's for: Anyone who read and admired Ruby's titanic 2022 essay on The Waste Land; lovers of poetry looking for a challenge. —SMS

How Sondheim Can Change Your Life by Richard Schoch [NF]

What it's about: Drama professor Schoch's tribute to Stephen Sondheim and the life lessons to be gleaned from his music.

Who it's for: Sondheim heads, former theater kids, end of list. —SMS

The Serviceberry by Robin Wall Kimmerer [NF]

What it is: 2022 MacArthur fellow and botanist Kimmerer, an enrolled member of the Citizen Potawatomi Nation, (re)introduces audiences to a flowering, fruiting native plant beloved of foragers and gardeners.

Who it’s for: The restoration ecologist in your life, along with anyone who loved Braiding Sweetgrass and needs a nature-themed holiday gift. —NodB

My Heart Belongs in an Empty Big Mac Container Buried Beneath the Ocean Floor by Homeless [F]

What it is: A pseudonymous, tenderly comic novel of blue whales and Golden Arches, mental illness and recovery.

Who it's for: Anyone who finds Thomas Pynchon a bit too staid. —JHM

Yoke and Feather by Jessie van Eerden [NF]

What it's about: Van Eerden's braided essays explore the "everyday sacred" to tease out connections between ancient myth and contemporary life.

Who it's for: Readers of Courtney Zoffness's Spilt Milk and Jeanna Kadlec's Heretic. —SMS

Camp Jeff by Tova Reich [F]

What it's about: A "reeducation" center for sex pests in the Catskills, founded by one Jeffery Epstein (no, not that one), where the dual phenomena of #MeToo and therapyspeak collide.

Who it's for: Fans of Philip Roth and Nathan Englander; cancel culture skeptics. —SMS

Selected Amazon Reviews by Kevin Killian [NF]

What it is: A collection of 16 years of Killian’s funniest, wittiest, and most poetic Amazon reviews, the sheer number of which helped him earn the rarefied “Top 100” and “Hall of Fame” status on the site.

Who it's for: Fans of Wayne Koestenbaum and Dodie Bellamy, who wrote introduction and afterword, respectively; people who actually leave Amazon reviews. —DF

Cher by Cher [NF]

What it is: The first in a two-volume memoir, telling the story of Cher's early life and ascendent career as only she can tell it.

Who it's for: Anyone looking to fill the My Name Is Barbra–sized hole in their heart, or looking for something to tide them over until the Liza memoir drops. —SMS

The City and Its Uncertain Walls by Haruki Murakami, tr. Philip Gabriel [F]

What it is: Murakami’s first novel in over six years returns to the high-walled city from his 1985 story "Hard-Boiled Wonderland and the End of the World" with one man's search for his lost love—and, simultaneously, an ode to libraries and literature itself.

Who it's for: Murakami fans who have long awaited his return to fiction. —DF

American Bulk by Emily Mester [NF]

What it's about: Reflecting on what it means to "live life to the fullest," Mester explores the cultural and personal impacts of America’s culture of overconsumption, from Costco hauls to hoarding to diet culture—oh my!

Who it's for: Lovers of sustainability; haters of excess; skeptics of the title essay of Becca Rothfeld's All Things Are Too Small. —DF

The Icon and the Idealist by Stephanie Gorton [NF]

What it is: A compelling look at the rivalry between Margaret Sanger, of Planned Parenthood fame, and Mary Ware Dennett, who each held radically different visions for the future of birth control.

Who it's for: Readers of Amy Sohn's The Man Who Hated Women and Katherine Turk's The Women of NOW; anyone interested in the history of reproductive rights. —SMS

December

Rental House by Weike Wang [F]

What it's about: Married college sweethearts invite their drastically different families on a Cape Code vacation, raising questions about marriage, intimacy, and kinship.

Who it's for: Fans of Wang's trademark wit and sly humor (see: Joan Is Okay and Chemistry); anyone with an in-law problem.

Woo Woo by Ella Baxter [F]

What it's about: A neurotic conceptual artist loses her shit in the months leading up to an exhibition that she hopes will be her big breakout, poking fun at the tropes of the "art monster" and the "woman of the verge" in one fell, stylish swoop.

Who it's for: Readers of Sheena Patel's I'm a Fan and Chris Kraus's I Love Dick; any woman who is grateful to but now also sort of begrudges Jenny Offil for introducing "art monster" into the lexicon (me). —SMS

Berlin Atomized by Julia Kornberg, tr. Jack Rockwell and Julia Kornberg [F]

What it's about: Spanning 2001 to 2034, three Jewish and downwardly mobile siblings come of age in various corners of the world against the backdrop of global crisis.

Who it's for: Fans of Catherine Lacey's Biography of X and Joshua Cohen's The Netanyahus. —SMS

Sand-Catcher by Omar Khalifah, tr. Barbara Romaine [F]

What it is: A suspenseful, dark satire of memory and nation, in which four young Palestinian journalists at a Jordanian newspaper are assigned to interview an elderly witness to the Nakba, the violent 1948 expulsion of native Palestinians from Israel—but to their surprise, the survivor doesn’t want to rehash his trauma for the media.

Who it’s for: Anyone looking insight—tinged with grim humor—into the years leading up to the present political crisis in the Middle East and the decades-long goal of Palestinian autonomy. —NodB

The Shutouts by Gabrielle Korn [F]

What it's about: In the dystopian future, mysteriously connected women fight to survive on the margins of society amid worsening climate collapse.

Who it's for: Fans of Korn's Yours for the Taking, which takes place in the same universe; readers of Becky Chambers and queer-inflected sci-fi. —SMS

What in Me Is Dark by Orlando Reade [NF]

What it's about: The enduring, evolving influence of Milton's Paradise Lost on political history—and particularly on the work of 12 revolutionary readers, including Malcom X and Hannah Arendt.

Who it's for: English majors and fans of Ryan Ruby and Sarah Bakewell—but I repeat myself. —SMS

The Afterlife Is Letting Go by Brandon Shimoda [NF]

What it's about: Shimoda researches the mass incarceration of Japanese Americans during WWII, and speaks with descendants of those imprisoned, for this essay collection about the “afterlife” of cruelty and xenophobia in the U.S.

Who it’s for: Anyone to ever visit a monument, museum, or designated site of hallowed ground where traumatic events have taken place. —NodB

No Place to Bury the Dead by Karina Sainz Borgo, tr. Elizabeth Bryer [F]

What it's about: When Angustias Romero loses both her children while fleeing a mysterious disease in her unnamed Latin American country, she finds herself in a surreal, purgatorial borderland where she's soon caught in a power struggle.

Who it's for: Fans of Maríana Enriquez and Mohsin Hamid. —SMS

The Rest Is Silence by Augusto Monterroso, tr. Aaron Kerner [F]

What it is: The author of some of the shortest, and tightest, stories in Latin American literature goes long with a metafictional skewering of literary criticism in his only novel.

Who it's for: Anyone who prefers the term "palm-of-the-hand stories" to "flash fiction." —JHM

Tali Girls by Siamak Herawi, tr. Sara Khalili [F]

What it is: An intimate, harrowing, and vital look at the lives of girls and women in an Afghan mountain village under Taliban rule, based on true stories.

Who it's for: Readers of Nadia Hashimi, Akwaeke Emezi, and Maria Stepanova. —SMS

Sun City by Tove Jansson, tr. Thomas Teal [F]

What it's about: During her travels through the U.S. in the 1970s, Jansson became interested in the retirement home as a peculiarly American institution—here, she imagines the tightly knit community within one of them.

Who it's for: Fans of Jansson's other fiction for adults, much of which explores the lives of elderly folks; anyone who watched that documentary about The Villages in Florida. —SMS

Editor's note: We're always looking to make our seasonal book previews more useful to the readers, writers, and critics they're meant to serve. Got an idea for how we can improve our coverage? Tell me about it at sophia@themillions.com.

[millions_email]

Discovering Ourselves: The Millions Interviews Well-Read Black Girl Glory Edim

Reading Well-Read Black Girl, an anthology of essays by Black women writers, is like finding your favorite books compiled in one place and then getting to see the radiance and sorrow and joy that went into their creation. Glory Edim’s book includes work by Jesmyn Ward, Marita Golden, Tayari Jones, Kaitlyn Greenidge, Dhonielle Clayton, Gabourey Sidibe, and Jacqueline Woodson, to name a few. Each contributor offers a personal account of her literary journey, how it felt growing up without Black characters on the page, and/or the joy of finding themselves mirrored in literature. They describe how their own reading and writing weaves into their larger community stories.

Before she published Well-Read Black Girl, Edim had developed an enthusiastic following of readers who eagerly lap up her book club recommendations and participate in her annual festival celebrating literature by Black women. I had the good fortune to catch up with her at Washington, D.C.’s Busboys and Poets. Glory had just come from visiting the elementary school where her brother teaches. The students there wanted to become writers, and sought her advice on finding literary agents (!).

Glory was appearing in conversation with acclaimed DC-based writer Marita Golden. Among a lifetime of marvelous literary contributions, Marita founded the Hurston Wright Foundation, which supports emerging and midcareer Black writers and preserves and disseminates the rich legacy of African American writing. Marita’s essay in Well-Read Black Girl, “Zora and Me,” is a poignant journey through her own literary maturation:

Like Zora I lost my mother at a young age and warred with a father I loved, it seemed, more than life. Like Zora I stepped over the ashes and debris of loss and struck out on my own, carrying grief and anger on my shoulders.Zora’s mother told her to jump at the sun. My mother told me that one day I would write a book.

Marita pointed out that book clubs are part of the Emancipation story. Following the Civil War, African-American women played a huge role in keeping books in print; books were an important social and economic force.

The Millions: Can you tell us how you got started reading and writing?

Glory Edim: My parents are Nigerian. They came here in search of a better life. I think about how life could have been completely different if they had taken a different path. I grew up in Washington, D.C., and being here is like a homecoming.

After my parents divorced, my father moved back to Nigeria, and we traveled back and forth every summer. Those travels are so much part of who I am.

My mother was a huge influence. She took us to the Smithsonian museums. She would ask us to find a painting that we would like to put on our living room wall and have us talk about it. She took us to all kinds of D.C. cultural events. D.C. was our playground. She read to me every night. Reading aloud is to witness ourselves.

I went to Howard University and was incredibly inspired to be around so much Black excellence in a space that was like love. A big part of my book is trying to recreate the feeling I had at Howard.

After Howard, I worked at the Lincoln Theatre in D.C., where I saw many wonderful plays, and began to think about dialogue in novels. That work made me think about what pulls a reader into a book. What generates an emotional response? I found that it’s important to think across art forms, and study great works of art for their structures.

TM: Tell us about the origin of Well-Read Black Girl, the persona.

GE: My partner gave me a tee shirt for my 31st birthday that said “Well-Read Black Girl.” By then I was living in New York. When I wore it, all kinds of people stopped me to talk about books they loved and ask for book recommendations. The level of interest inspired me to start a book club. More than anything, I wanted to make connections and foster relationships. I saw that people in New York were craving community.

I have a special interest in debut novels. I invited Naomi Jackson to our first book club to talk about her debut novel, The Star Side of Bird Hill. She brought along her friend Natalie Diaz, an incredible poet who just won a MacArthur Genius award. Things went from there.

I was lucky to have a job at Kickstarter, which is filled with techies who read and are engaged in other creative pursuits. I was able to use Kickstarter to launch the Well-Read Black Girl Festival in 2017, which is a cultural event, meant to promote community.

Timing is everything. My work coincided with the start of the Black Lives Matter movement, and online organizing was catching on quickly. Social media is an important part of what I do. Still, there is nothing like holding a real paper book in your hand; there’s nothing like reading a book from the library. One reason for this collection is to take the conversation offline and onto the pages of a book.

TM: Readers are always interested in process. Can you talk a little about that?

GE: I read widely and deeply. I’ve always been curious about the stories of writers. Who inspired them to write? When did they first declare themselves a writer? Beginnings have a significance. In the anthology, we discover how it began for each writer.

When I read for the book club, I read both as a facilitator and as an editor. These are two different roles. I am a lover of art; I study how people put things together.

TM: How did you decide to organize your collection?

GE: I organized it according to my personal taste. I considered my own literary memories and pulled from there. The essays are meant to feel like a conversation. As I prepared to invite contributors, I returned to the pivotal work of Toni Morrison, Cade Bambara, Zora Neale Hurston, and Audre Lorde. The essays I selected are heartfelt, precise, and genuine. Whether you are 16 or 65, I want the reader to be hit with a sense of nostalgia. My hope is that the collection encourages readers to share their own stories.

TM: How did you reach out to other writer/contributors and what was their response?

GE: I had a relationship with a majority of authors—as mentors, book club authors, or fans on social media. Each contributor was generous with their time.

TM: What’s next for you?

GE: You mean beyond growing our community?

I am working on a memoir with my mother. She was severely depressed while I was in college. The whole family came together to help her. Since this was a deeply private experience for her, she is the only one who can tell that story. But it is so much about my family’s legacy that I hope to get it on the page.

I’m always reading. Have you read Dr. Imani Perry’s Looking for Lorraine? It’s about author and playwright and activist Lorraine Hansberry. It’s a must read!

A Brief Caribbean Reading List

Among the string of islands known as the Lesser Antilles lies St. Lucia, famous for the picturesque twin volcanic peaks—Gros Piton and Petit Piton—that rise sharply from the sea. Beyond the beaches and lush rainforests that draw tourists are the simple villages and remnants of a colonial past that inspired the Nobel Laureate Derek Walcott.

Reading Walcott’s poetry is akin to walking the streets of his childhood, beneath fragrant frangipani trees, brushing up against the hybrid languages and people. Walcott’s work—an ode to the island where he was born—is intimately tied to St Lucia.

Like Walcott, these four Caribbean writers celebrate their complicated homelands. Setting aside what’s been in the news of late—flippant, dismissive comments from politicians about Africa, Haiti, and by extension, the entire African diaspora—these four Caribbean writers take you to the heart and soul of Caribbean living, while tackling big issues—from natural disasters and their aftermath to mental illness and the underbelly of tourism.

Haiti

Recent news cycle aside, Haiti today is remembered for the 7.0 magnitude earthquake that struck near Port-au-Prince, taking nearly 300,000 lives. Katia D. Ulysse’s Mouths Don’t Speak takes readers back to the earthquake and its aftermath. With no word from her parents following the earthquake, Jacqueline Florestant presumes her parents died and mourns their loss. She returns to Haiti, which she hasn’t visited since she left 25 years earlier. Seen through the eyes of an expatriate, the Haiti of Jacqueline’s childhood is no more.

Along with the destruction of the country of her childhood, Jacqueline struggles with her husband’s battles with post-traumatic stress disorder from his stint in the military, deception, and more deaths of the people around her.

Far from the brutal regimes of dictatorship—one of the stories we read so often about Haiti— Mouths Don’t Speak tells a story of Haiti we don’t always hear.

Barbados

“The people on the hill liked to say that God’s smile was the sun shining down on them.” So begins Naomi Jackson’s Star Side of Bird Hill, which follows two New York girls sent to live with their grandmother in Barbados when their mother can no longer take care of them. The two sisters, age 10 and 16, experience the Bird Hill community and Barbados through the lens of their Brooklyn upbringing. And through that lens, the “sea explode[s] her sense of wonder, especially when the dense tree cover gave way to the blue-blue water lapping against the shore,” and the “sea got gobbled up by the hotels and resorts, only peeking out between openings in the concrete.”

Before their exile, the girls are virtually on their own, with Dionne, the 16-year-old, standing in as mother to her younger sister. In Barbados, the girls are under the watchful eye of their grandmother, with Dionne trying to shake her grandmother’s grip and the younger Phaedra accompanying her grandmother—a midwife—to deliver babies and trying to get at heart of the mysteries of her mother’s life.

[millions_ad]

This coming-of-age story is a window into small-town island life and the interwoven lives of the many characters who inhabit Bird Hill.

Jamaica

The Montego Bay where Nicole Dennis-Benn’s Here Comes the Sun is set isn’t your typical tourist destination. Yes, there is a glitzy resort set apart from everyday life in Montego Bay, where Margo works and carries on late-night trysts with male guests to make extra money. And there is River Bank where Margo’s sister and mother live—a different world altogether from the manicured lawns and lush gardens in the resort areas.

Here Comes the Sun is a look at what sisters, Margo and Thandie, believe it takes to break out of the societal constraints into which they were born. Margo trades her body for money, which she saves to pay for her sister’s education and save her from a life similar to her own. The younger Thandi bleaches her skin to achieve what she thinks is the epitome of beauty and success.

And it’s a study of the courage to love without restrictions, as well as the hidden lives of the many employees away from the glitz of the resorts.

Trinidad

Lauren Francis-Sharma’s 'Till the Well Runs Dry teems with forbidden love and the secrets that undo relationships. Sixteen-year-old Marcia Garcia meets a policeman, Farouk, of East Indian descent, who, in turn, seeks the help of an obeah woman to make Marcia fall in love with him. She does, but their marriage falls apart before it even has a chance to begin. Despite Marcia and Farouk’s failed marriage, they have four children together, and the children’s voices are an integral part of this family tale.

There are secrets, lots of them. Early in the novel, two children under Marcia’s care disappear without a trace. Not only is the fate of the two boys who could not have left on their own a mystery, but so is their parentage.

From Toco to Blanchisseuse, the villages are authentic places you can visit—from your armchair or in person—on Trinidad’s north coast. 'Till the Well Runs Dry is a great primer of life near the north coast beaches.

Image Credit: Wikimedia Commons.

You Can’t Go Wrong With Heart: The Millions Interviews Jami Attenberg

I'd been hearing about Jami Attenberg's latest novel, All Grown Up, long before it went on sale. Early readers loved it, and their praise produced a kind of roar across the Internet, one full of joy and ferocity. People were grateful for this story and this character: Andrea Bern, a single woman who doesn't have kids, and doesn't want them. When I finally got my hands on a copy, I saw what everyone was talking about; Andrea is like so many women I know, and yet, she is unlike most female characters in fiction. She is also more than her demographic (as we all are). Through a series of droll but big-hearted and compassionate vignettes, Attenberg depicts a profound and authentic portrait of a woman as she moves through this beautiful yet often unjust world. In All Grown Up, there is joy, loneliness, pleasure, despair, grief, hope, frivolity, and matters of great import.

Jami Attenberg is The New York Times bestselling author of five other books, including The Middlesteins and Saint Mazie. She was kind enough to answer my questions via email.

The Millions: All Grown Up is told in a series of vignettes about Andrea's life -- there's one terrific, pithy chapter early on, for instance, called, simply, "Andrea," about how everyone keeps recommending the same book about being single. There are a few chapters about Andrea's friend Indigo: in one she gets married, in another she has child, and so on. Some are about Andrea's dating life, and others focus on her family. I'm curious about how working within this structure affected your understanding of Andrea herself, seeing as she comes into focus story by story, but not in a traditional, chronological way. I also wonder what you want the reader to feel, seeing her from these various angles, some of which overlap, while others don't.

Jami Attenberg: I made a list -- I wish I could find it now; it’s in a notebook somewhere -- of all these different parts of being an adult. For example: your relationship with your family, your career, your living situation, etc. And then I created story cycles around them, and often they were spread out over decades. As an example: what Andrea’s apartment was like when she was growing up versus how she felt about her apartment as an adult in her late 20s versus her late 30s, and how those memories informed her feelings of safety and security and space. A sense of home is a universal topic. And then eventually more relevant, nuanced parts of a specifically female adulthood emerged as I wrote, and little cycles formed around those subjects. So the writing of this book in terms of structure was really an accrual of these cycles.

The goal was to tell the whole truth about this character, and why she had become the person she was -- the adult she was, I guess -- so that she could understand it/herself, and move on from it. The fact that it’s not linear is true to the story of our lives. The moments that inform our personalities come at us at different times. If you were to make a “What Makes Me the Way I Am” top 10 list in order of importance, there’s no way it would be in chronological order. And to me they’re all connected. I’d hope readers see some of their own life challenges in her, and if not her, in some of the other characters, even if they happen at different times. Everything keeps looping around again anyway. (We can’t escape our pasts, we are doomed to repeat ourselves, we are our parents, etc.)

TM: In my mind, and likely in the minds of others, you lead an ideal "writer's life" -- you're pretty prolific, for one, and you also don't teach. You now live in two places: New Orleans and New York City -- which seems chic and badass to me. Plus you have a dog with the perfect under bite! Can you talk a little about your day-to-day life as an artist, and what you think it's taken (besides, say, the stars aligning), to get there? Any advice for writers who want to be like you when they're all grown up?

JA: It took me a long time to figure out what would make me happy, and this existence seems to be it, for a while anyway. I’m 45 now, and I started planning for this life a few years ago, but before then I had no vision except to keep writing, and that was going to be enough for me. Then, after my third winter stay in New Orleans, I realized I had truly fallen in love with the city. And then I had a dream, an actual adult goal. I had two cities I loved, and I wanted to be in both. So it has meant a lot to me to get to this place. I worked so hard to get here! I continue to work hard. No one hands it to you, I can tell you that much, unless you are born rich, which I was not, and even then that’s just money, it’s not exactly a career. And I think the career part, the getting to write and be published and be read part, is the most gratifying of all. Unless success is earned it is not success at all.

My day-to-day life is wake, read, drink coffee, walk the dog, say hi to my neighbors, come home, be extremely quiet for hours, write, read, look at the Internet, eat, walk the dog, have a drink, freak out about the state of America, and have some dinner, maybe with friends. Soon I’ll be on tour for two months, and that will be a whole different way of living, though still part of my professional life. But when I am writing, it is a quiet and simple existence in which I take my work seriously. I have no advice at all to anyone except to keep working as hard as you possibly can.

TM: I've always loved the sensuality of your writing. Whether the prose is describing eating, or having sex, or simply the varied textures of life in New York City, we are with your characters, inside their bodies. What is the process for you, in terms of inhabiting a character's physical experience? Does it happen on the sentence level, or as you enter the fictive dream, or what?

JA: Well thank you, Edan. I’m a former poet, for starters, so I’m always looking to up the language in a specific kind of way. I certainly close my eyes and try to be in the room with a character, and inside their flesh as well, I suppose. I write things to turn myself on. Even my bad sex scenes are in a strange way arousing to me, even if it’s just because they make me laugh. It’s all playtime for me.

All of this kind of thinking comes in the early stages but also in my final edits of the second draft. Most of the lyricism of the work is done before I send the book out to my editor. Her notes to me address the nuts and bolts of plot and architecture, and often also emotions and character motivation. But the language, for the most part, she leaves to me.

TM: My favorite relationship in the novel is between Andrea and her mother. It's loving and comforting even though there are also real tensions and conflicts between them. Can you talk about creating a nuanced, and thus realistic, portrayal of mother and daughter?

JA: It is also my favorite relationship! I could write the two of them forever. I am satisfied with the book as it stands but would still love to write a chapter where the two of them go to the Women’s March together, and Andrea’s mother knits her a pussy hat and Andrea doesn’t want to wear it because she only ever wears black. I have pages and pages of dialogue between them that I never used but wrote anyway just because they were fun together, or fun for me the author, but maybe not fun between the two of them.

Their relationship really comes from living in New York City for 18 years and watching New York mothers and daughters together out in the world and just channeling that. These characters are very much a product of eavesdropping. I try to approach these kinds of family relationships like this: everyone is always wrong and everyone is always right. Like their patterns and emotions are already so ingrained that there’s no way out of it except through, because no one will ever win. But also there is love. Always there is love. And that’s how I know they’ll make it to the other side.

TM: This novel has so many terrific female characters, who are at once immediately recognizable (sort of like tropes of contemporary womanhood, if that makes sense) and also unique. Aside from Andrea and her mother, there is Andrea's sister-in-law, Greta, a once elegant and willowy magazine editor who is depleted (spiritually and otherwise) by her child's illness; Indigo, ethereal yoga teacher turned rich wife and mother, and then divorcée and single mother; the actress with the great shoes who moves into Andrea's building; Andrea's younger and (seemingly?) self-possessed coworker Nina. They're all magnetic -- and they also all fail to hold onto that magnetism. Their cool grace, at least in Andrea's eyes, is tarnished, often by the burdens of life itself. Did you set out to have these women orbiting Andrea, contrasting her, sometimes echoing her, or was there another motivation in mind?

JA: These women were all there from the beginning -- all of them. I had to grow them and inform them, but there were no surprise appearances. I never thought -- oh where did she come from? They were all just real women living and working in today’s New York City, and also they were real women who lived inside of me. I needed each of these women to be in the book or it wouldn’t have been complete. And also I certainly needed them to question Andrea. For example, her sister-in-law in particular sometimes acts as a stand-in for what I imagine the reader must be thinking, while her mother acts as a stand-in for me, both of them interrogating Andrea at various times.

And also always, always, always in my work the female characters are going to be the most interesting. Most of the chapters are named after women. I had no doubt in my mind that I wanted a collective female energy to buoy this book. We’re always steering the fucking ship, whether it’s acknowledged or not.

TM: Were there any models for this book in terms of voice, structure, tone of subject? Are there, in general, any authors and novels that are "fairy godmothers" for you and your writing?

JA: Each book is different, I have a different reading list, but Grace Paley is my mothership no matter what, because of her originality, grasp of voice and dialect, and incredible heart and compassion.

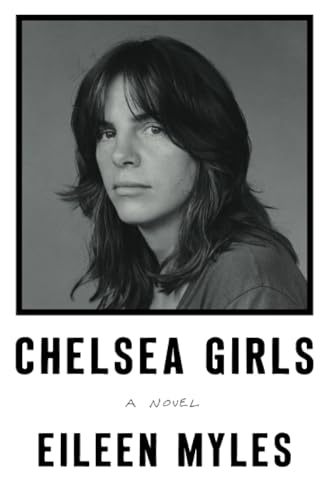

As I began writing All Grown Up, I was reading Patti Smith’s M Train and Maggie Nelson’s The Argonauts, and when I was halfway done with the book I started reading Eileen Myles’s Chelsea Girls. I was not terribly interested in fiction for the most part. I wanted this book to feel memoiristic -- not like an actual memoir, that one writes and tries to put in neat little box, perfect essays or chapters, but just genuinely like this woman was telling you every single goddamn, messy thing you needed to know about her life.

Those three books all feel like unique takes on the memoir. Patti Smith just talks about whatever the fuck she wants to talk about, and Maggie Nelson writes in those short, meticulous, highly structured bursts, where you genuinely feel like she is making her case, and in Chelsea Girls Eileen has this dreamy, meandering quality, although she knows exactly what she’s doing, she’s scooping you up and putting you in her pocket and taking you with her wherever she wants to go. So all of those books somehow connected together for me while I was establishing the feel of this book.

And when I was finishing I read Naomi Jackson’s gorgeous debut, The Star Side of Bird Hill, which is also about family and a collection of strong women and coming of age, although the people growing up in her book are much younger than my narrator. But it was just stunning, and it made me cry, and the emotions felt so real and true. So I think reading her was an excellent inspiration as I wrote those final pages. Like you can’t go wrong with heart.

TM: Since is The Millions, I must ask you: What was the last great book you read?

JA: I just judged the Pen/Bingham contest and all of the books on our shortlist were wonderful: Insurrections by Rion Amilcar Scott; We Show What We Have Learned by Clare Beams; The Mothers by Brit Bennett; Homegoing by Yaa Gyasi, and Hurt People by Cote Smith.