Mentioned in:

The Great Fall 2024 Book Preview

With the arrival of autumn comes a deluge of great books. Here you'll find a sampling of new and forthcoming titles that caught our eye here at The Millions, and that we think might catch yours, too. Some we’ve already perused in galley form; others we’re eager to devour based on their authors, plots, or subject matters. We hope your next fall read is among them.

—Sophia Stewart, editor

October

Season of the Swamp by Yuri Herrera, tr. Lisa Dillman [F]

What it is: An epic, speculative account of the 18 months that Benito Juárez spent in New Orleans in 1853-54, years before he became the first and only Indigenous president of Mexico.

Who it's for: Fans of speculative history; readers who appreciate the magic that swirls around any novel set in New Orleans. —Claire Kirch

The Black Utopians by Aaron Robertson [NF]

What it is: An exploration of Black Americans' pursuit and visions of utopia—both ideological and physical—that spans the Reconstruction era to the present day and combines history, memoir, and reportage.

Who it's for: Fans of Saidiya Hartman's Wayward Lives, Beautiful Experiments and Kristen R. Ghodsee's Everyday Utopia. —Sophia M. Stewart

The Third Realm by Karl Ove Knausgaard, tr. Martin Aitken [F]

What it is: The third installment in Knausgaard's Morning Star series, centered on the appearance of a mysterious new star in the skies above Norway.

Who it's for: Real Knausgaard heads only—The Wolves of Eternity and Morning Star are required reading for this one. —SMS

Brown Women Have Everything by Sayantani Dasgupta [NF]

What it is: Essays on the contradictions and complexities of life as an Indian woman in America, probing everything from hair to family to the joys of travel.

Who it's for: Readers of Durga Chew-Bose, Erika L. Sánchez, and Tajja Isen. —SMS

The Plot Against Native America by Bill Vaughn [F]

What it is: The first narrative history of Native American boarding schools— which aimed "civilize" Indigenous children by violently severing them from their culture— and their enduring, horrifying legacy.

Who it's for: Readers of Ned Blackhawk and Kathleen DuVal. —SMS

The Mighty Red by Louise Erdrich [F]

What it is: Erdrich's latest novel set in North Dakota's Red River Valley is a tale of the intertwined lives of ordinary people striving to survive and even thrive in their rural community, despite environmental upheavals, the 2008 financial crisis, and other obstacles.

Who it's for: Readers of cli-fi; fans of Linda LeGarde Grover and William Faulkner. —CK

The Position of Spoons by Deborah Levy [NF]

What it is: The second book from Levy in as many years, diverging from a recent streak of surrealist fiction with a collection of essays marked by exceptional observance and style.

Who it's for: Close lookers and the perennially curious. —John H. Maher

The Bog Wife by Kay Chronister [F]

What it's about: The Haddesley family has lived on the same West Virginia bog for centuries, making a supernatural bargain with the land—a generational blood sacrifice—in order to do so—until an uncovered secret changes everything.

Who it's for: Readers of Karen Russell and Jeff VanderMeer; anyone who has ever used the phrase "girl moss." —SMS

The Great When by Alan Moore [F]

What it's about: When an 18-year old book reseller comes across a copy of a book that shouldn’t exist, it threatens to upend not just an already post-war-torn London, but reality as we know it.

Who it's for: Anyone looking for a Sherlock Holmes-style mystery dipped in thaumaturgical psychedelia. —Daniella Fishman

The Message by Ta-Nehisi Coates [NF]

What it's about: One of our sharpest critical thinkers on social justice returns to nonfiction, nearly a decade after Between the World and Me, visiting Dakar, to contemplate enslavement and the Middle Passage; Columbia, S.C., as a backdrop for his thoughts on Jim Crow and book bans; and the Israeli-occupied West Bank, where he sees contemporary segregation in the treatment of Palestinians.

Who it’s for: Fans of James Baldwin, George Orwell, and Angela Y. Davis; readers of Nikole Hannah-Jones’s The 1619 Project and Isabel Wilkerson’s Caste, to name just a few engagements with national and racial identity. —Nathalie op de Beeck

Abortion by Jessica Valenti [NF]

What it is: Columnist and memoirist Valenti, who tracks pro-choice advocacy and attacks on the right to choose in her Substack, channels feminist rage into a guide for freedom of choice advocacy.

Who it’s for: Readers of Robin Marty’s The New Handbook for a Post-Roe America, #ShoutYourAbortion proponents, and followers of Jennifer Baumgartner’s [I Had an Abortion] project. —NodB

Gifted by Suzuki Suzumi, tr. Allison Markin Powell [F]

What it's about: A young sex worker in Tokyo's red-light district muses on her life and recounts her abusive mother's final days, in what is Suzuki's first novel to be translated into English.

Who it's for: Readers of Susan Boyt and Mieko Kanai; fans of moody, introspective fiction; anyone with a fraught relationship to their mother. —SMS

Childish Literature by Alejandro Zambra, tr. Megan McDowell [F]

What it is: A wide-ranging collection of stories, essays, and poems that explore childhood, fatherhood, and family.

Who it's for: Fans of dad lit (see: Lucas Mann's Attachments, Keith Gessen's Raising Raffi, Karl Ove Knausgaard's seasons quartet, et al). —SMS

Books Are Made Out of Books ed. Michael Lynn Crews [NF]

What it is: A mining of the archives of the late Cormac McCarthy with a focus on the famously tight-lipped author's literary influences.

Who it's for: Anyone whose commonplace book contains the words "arquebus," "cordillera," or "vinegaroon." —JHM

Slaveroad by John Edgar Wideman [F]

What it is: A blend of memoir, fiction, and history that charts the "slaveroad" that runs through American history, spanning the Atlantic slave trade to the criminal justice system, from the celebrated author of Brothers and Keepers.

Who it's for: Fans of Clint Smith and Ta-Nehisi Coates. —SMS

Linguaphile by Julie Sedivy [NF]

What it's about: Linguist Sedivy reflects on a life spent loving language—its beauty, its mystery, and the essential role it plays in human existence.

Who it's for: Amateur (or professional) linguists; fans of the podcast A Way with Words (me). —SMS

An Image of My Name Enters America by Lucy Ives [NF]

What it is: A collection of interrelated essays that connect moments from Ives's life to larger questions of history, identity, and national fantasy,

Who it's for: Fans of Ives, one of our weirdest and most wondrous living writers—duh; anyone with a passing interest in My Little Pony, Cold War–era musicals, or The Three Body Problem, all of which are mined here for great effect. —SMS

Women's Hotel by Daniel Lavery [F]

What it is: A novel set in 1960s New York City, about the adventures of the residents of a hotel providing housing for young women that is very much evocative of the real-life legendary Barbizon Hotel.

Who it's for: Readers of Mary McCarthy's The Group and Rona Jaffe's The Best of Everything. —CK

The World in Books by Kenneth C. Davis [NF]

What it is: A guide to 52 of the most influential works of nonfiction ever published, spanning works from Plato to Ida B. Wells, bell hooks to Barbara Ehrenreich, and Sun Tzu to Joan Didion.

Who it's for: Lovers of nonfiction looking to cover their canonical bases. —SMS

Blue Light Hours by Bruna Dantas Lobato [F]

What it's about: Through the emanating blue-glow of their computer screens, a mother and daughter, four-thousand miles apart, find solace and loneliness in their nightly Skype chats in this heartstring-pulling debut.

Who it's for: Someone who needs to be reminded to CALL YOUR MOTHER! —DF

Riding Like the Wind by Iris Jamahl Dunkle [NF]

What it is: The biography of Sanora Babb, a contemporary of John Steinbeck's whose field notes and interviews with Dust Bowl migrants Steinbeck relied upon to write The Grapes of Wrath.

Who it's for: Steinbeck fans and haters alike; readers of Kristin Hannah's The Four Winds and the New York Times Overlooked column; anyone interested in learning more about the Dust Bowl migrants who fled to California hoping for a better life. —CK

Innie Shadows by Olivia M. Coetzee [F]

What it is: a work of crime fiction set on the outskirts of Cape Town, where a community marred by violence seeks justice and connection; also the first novel to be translated from Kaaps, a dialect of Afrikaans that was until recently only a spoken language.

Who it's for: fans of sprawling, socioeconomically-attuned crime dramas a la The Wire. —SMS

Dorothy Parker in Hollywood by Gail Crowther [NF]

What it is: A history of the famous wit—and famous New Yorker—in her L.A. era, post–Algonquin Round Table and mid–Red Scare.

Who it's for: Owners of a stack of hopelessly dog-eared Joan Didion paperbacks. —JHM

The Myth of American Idealism by Noam Chomsky and Nathan J. Robinson [NF]

What it is: A potent critique of the ideology behind America's foreign interventions and its status as a global power, and an treatise on how the nation's hubristic pursuit of "spreading democracy" threatens not only the delicate balance of global peace, but the already-declining health of our planet.

Who it's for: Chomskyites; policy wonks and casual critics of American recklessness alike. —DF

Mysticism by Simon Critchley [NF]

What it is: A study of mysticism—defined as an experience, rather than religious practice—by the great British philosopher Critchley, who mines music, poetry, and literature along the way.

Who it's for: Readers of John Gray, Jorge Luis Borges, and Simone Weil. —SMS

Q&A by Adrian Tomine [NF]

What it is: The Japanese American creator of the Optic Nerve comic book series for D&Q, and of many a New Yorker cover, shares his personal history and his creative process in this illustrated unburdening.

Who it’s for: Readers of Tomine’s melancholic, sometimes cringey, and occasionally brutal collections of comics short stories including Summer Blonde, Shortcomings, and Killing and Dying. —NodB

Sonny Boy by Al Pacino [NF]

What it is: Al Pacino's memoir—end of description.

Who it's for: Cinephiles; anyone curious how he's gonna spin fumbling Diane Keaton. —SMS

Seeing Baya by Alice Kaplan [NF]

What it is: The first biography of the enigmatic and largely-forgotten Algerian artist Baya Mahieddine, who first enchanted midcentury Paris as a teenager.

Who it's for: Admirers of Leonora Carrington, Hilma af Klint, Frida Kahlo, and other belatedly-celebrated women painters. —SMS

Absolution by Jeff VanderMeer [F]

What it is: A surprise return to the Area X, the stretch of unforbidding and uncanny coastline in the hit Southern Reach trilogy.

Who it's for: Anyone who's heard this song and got the reference without Googling it. —JHM

The Four Horsemen by Nick Curtola [NF]

What it is: The much-anticipated cookbook from the team behind Brooklyn's hottest restaurant (which also happens to be co-owned by James Murphy of LCD Soundsystem).

Who it's for: Oenophiles; thirty-somethings who live in north Williamsburg (derogatory). —SMS

Seeing Further by Esther Kinsky, tr. Caroline Schmidt [F]

What it's about: An unnamed German woman embarks on the colossal task of reviving a cinema in a small Hungarian village.

Who it's for: Fans of Jenny Erpenbeck; anyone charmed by Cinema Paradiso (not derogatory!). —SMS

Ripcord by Nate Lippens [NF]

What it's about: A novel of class, sex, friendship, and queer intimacy, written in delicious prose and narrated by a gay man adrift in Milwaukee.

Who it's for: Fans of Brontez Purnell, Garth Greenwell, Alexander Chee, and Wayne Koestenbaum. —SMS

The Use of Photography by Annie Ernaux and Marc Marie, tr. Alison L. Strayer [NF]

What it's about: Ernaux's love affair with Marie, a journalist, while she was undergoing treatment for cancer, and their joint project to document their romance.

Who it's for: The Ernaux hive, obviously; readers of Sontag's On Photography and Janet Malcolm's Still Pictures. —SMS

Nora Ephron at the Movies by Ilana Kaplan [NF]

What it is: Kaplan revisits Nora Ephron's cinematic watersheds—Silkwood, Heartburn, When Harry Met Sally, You've Got Mail, and Sleepless in Seattle—in this illustrated book. Have these iconic stories, and Ephron’s humor, weathered more than 40 years?

Who it’s for: Film history buffs who don’t mind a heteronormative HEA; listeners of the Hot and Bothered podcast; your coastal grandma. —NodB

[millions_email]

The Philosophy of Translation by Damion Searls [NF]

What it is: A meditation on the act and art of translation by one of today's most acclaimed practitioners, best known for his translations of Fosse, Proust, et al.

Who it's for: Regular readers of Words Without Borders and Asymptote; professional and amateur literary translators alike. —SMS

Salvage by Dionne Brand

What it is: A penetrating reevaluation of the British literary canon and the tropes once shaped Brand's reading life and sense of self—and Brand’s first major work of nonfiction since her landmark A Map to the Door of No Return.

Who it's for: Readers of Christina Sharpe's Ordinary Notes and Elizabeth Hardwick's Seduction and Betrayal. —SMS

Masquerade by Mike Fu [F]

What it's about: Housesitting for an artist friend in present-day New York, Meadow Liu stumbles on a novel whose author shares his name—the first of many strange, haunting happenings that lead up to the mysterious disappearance of Meadow's friend.

Who it's for: fans of Ed Park and Alexander Chee. —SMS

November

The Beggar Student by Osamu Dazai, tr. Sam Bett [F]

What it is: A novella in the moody vein of Dazai’s acclaimed No Longer Human, following the 30-something “fictional” Dazai into another misadventure spawned from a hubristic spat with a high schooler.

Who it's for: Longtime readers of Dazai, or new fans who discovered the midcentury Japanese novelist via TikTok and the Bungo Stray Dogs anime. —DF

In Thrall by Jane DeLynn [F]

What it is: A landmark lesbian bildungsroman about 16-year-old Lynn's love affair with her English teacher, originally published in 1982.

Who it's for: Fans of Joanna Russ's On Strike Against God and Edmund White's A Boy's Own Story —SMS

Washita Love Child by Douglas Kent Miller [NF]

What it is: The story of Jesse Ed Davis, the Indigenous musician who became on of the most sought after guitarists of the late '60s and '70s, playing alongside B.B. King, Bob Dylan, John Lennon, and more.

Who it's for: readers of music history and/or Indigenous history; fans of Joy Harjo, who wrote the foreword. —SMS

Set My Heart on Fire by Izumi Suzuki, tr. Helen O'Horan [F]

What it is: Gritty, sexy, and wholly rock ’n’ roll, Suzuki’s first novel translated into English (following her story collection, Hit Parade of Tears) follows 20-year-old Izumi navigating life, love, and music in the underground scene in '70s Japan.

Who it's for: Fans of Meiko Kawakami, Ursula K. Le Guin, and Marlowe Granados's Happy Hour. —DF

Didion & Babitz by Lili Anolik [NF]

What it is: A dual portrait of Joan Didion and Eve Babitz, who are so often compared to—and pitted against—each other on the basis of their mutual Los Angeles milieu.

Who it's for: Fans or haters of either writer (the book is fairly pro-Babitz, often at Didion's expense); anyone who has the Lit Hub Didion tote bag. —SMS

The Endless Refrain by David Rowell [NF]

What it's about: How the rise of music streaming, demonitizing of artist revenue, and industry tendency toward nostalgia have laid waste to the musical landscape, and the future of music culture.

Who it's for: Fans of Kyle Chayka, Spence Kornhaber, and Lindsay Zoladz. —SMS

Every Arc Bends Its Radian by Sergio De La Pava [F]

What it is: A mind- and genre-bending detective story set in Cali, Colombia, that blends high-stakes suspense with rigorous philosophy.

Who it's for: Readers of Raymond Chandler, Thomas Pynchon, and Jules Verne. —SMS

Something Close to Nothing by Tom Pyun [F]

What it’s about: At the airport with his white husband Jared, awaiting a flight to Cambodia to meet the surrogate mother carrying their adoptive child-to-be, Korean American Wynn decides parenthood isn't for him, and bad behavior ensues.

Who it’s for: Pyun’s debut is calculated to cut through saccharine depictions of queer parenthood—could pair well with Torrey Peters’s Detransition, Baby. —NodB

Rosenfeld by Maya Kessler [F]

What it is: Kessler's debut—rated R for Rosenfeld—follows one Noa Simmons through the tumultuous and ultimately profound power play that is courting (and having a lot of sex with) the titular older man who soon becomes her boss.

Who it's for: Fans of Sex and the City, Raven Leilani’s Luster, and Coco Mellor’s Cleopatra and Frankenstein. —DF

Lazarus Man by Richard Price [F]

What it is: The former The Wire writer offers yet another astute chronicle of urban life, this time of an ever-changing Harlem.

Who it's for: Fans of Colson Whitehead's Crook Manifesto and Paul Murray's The Bee Sting—and, of course, The Wire. —SMS

Stranger Than Fiction by Edwin Frank [NF]

What it is: An astute curveball of a read on the development and many manifestations of the novel throughout the tumultuous 20th century.

Who it's for: Readers who look at a book's colophon before its title. —JHM

Letters to His Neighbor by Marcel Proust, tr. Lydia Davis

What it is: A collection of Proust’s tormented—and frequently hilarious—letters to his noisy neighbor which, in a diligent translation from Davis, stand the test of time.

Who it's for: Proust lovers; people who live below heavy-steppers. —DF

Context Collapse by Ryan Ruby [NF]

What it is: A self-proclaimed "poem containing a history of poetry," from ancient Greece to the Iowa Workshop, from your favorite literary critic's favorite literary critic.

Who it's for: Anyone who read and admired Ruby's titanic 2022 essay on The Waste Land; lovers of poetry looking for a challenge. —SMS

How Sondheim Can Change Your Life by Richard Schoch [NF]

What it's about: Drama professor Schoch's tribute to Stephen Sondheim and the life lessons to be gleaned from his music.

Who it's for: Sondheim heads, former theater kids, end of list. —SMS

The Serviceberry by Robin Wall Kimmerer [NF]

What it is: 2022 MacArthur fellow and botanist Kimmerer, an enrolled member of the Citizen Potawatomi Nation, (re)introduces audiences to a flowering, fruiting native plant beloved of foragers and gardeners.

Who it’s for: The restoration ecologist in your life, along with anyone who loved Braiding Sweetgrass and needs a nature-themed holiday gift. —NodB

My Heart Belongs in an Empty Big Mac Container Buried Beneath the Ocean Floor by Homeless [F]

What it is: A pseudonymous, tenderly comic novel of blue whales and Golden Arches, mental illness and recovery.

Who it's for: Anyone who finds Thomas Pynchon a bit too staid. —JHM

Yoke and Feather by Jessie van Eerden [NF]

What it's about: Van Eerden's braided essays explore the "everyday sacred" to tease out connections between ancient myth and contemporary life.

Who it's for: Readers of Courtney Zoffness's Spilt Milk and Jeanna Kadlec's Heretic. —SMS

Camp Jeff by Tova Reich [F]

What it's about: A "reeducation" center for sex pests in the Catskills, founded by one Jeffery Epstein (no, not that one), where the dual phenomena of #MeToo and therapyspeak collide.

Who it's for: Fans of Philip Roth and Nathan Englander; cancel culture skeptics. —SMS

Selected Amazon Reviews by Kevin Killian [NF]

What it is: A collection of 16 years of Killian’s funniest, wittiest, and most poetic Amazon reviews, the sheer number of which helped him earn the rarefied “Top 100” and “Hall of Fame” status on the site.

Who it's for: Fans of Wayne Koestenbaum and Dodie Bellamy, who wrote introduction and afterword, respectively; people who actually leave Amazon reviews. —DF

Cher by Cher [NF]

What it is: The first in a two-volume memoir, telling the story of Cher's early life and ascendent career as only she can tell it.

Who it's for: Anyone looking to fill the My Name Is Barbra–sized hole in their heart, or looking for something to tide them over until the Liza memoir drops. —SMS

The City and Its Uncertain Walls by Haruki Murakami, tr. Philip Gabriel [F]

What it is: Murakami’s first novel in over six years returns to the high-walled city from his 1985 story "Hard-Boiled Wonderland and the End of the World" with one man's search for his lost love—and, simultaneously, an ode to libraries and literature itself.

Who it's for: Murakami fans who have long awaited his return to fiction. —DF

American Bulk by Emily Mester [NF]

What it's about: Reflecting on what it means to "live life to the fullest," Mester explores the cultural and personal impacts of America’s culture of overconsumption, from Costco hauls to hoarding to diet culture—oh my!

Who it's for: Lovers of sustainability; haters of excess; skeptics of the title essay of Becca Rothfeld's All Things Are Too Small. —DF

The Icon and the Idealist by Stephanie Gorton [NF]

What it is: A compelling look at the rivalry between Margaret Sanger, of Planned Parenthood fame, and Mary Ware Dennett, who each held radically different visions for the future of birth control.

Who it's for: Readers of Amy Sohn's The Man Who Hated Women and Katherine Turk's The Women of NOW; anyone interested in the history of reproductive rights. —SMS

December

Rental House by Weike Wang [F]

What it's about: Married college sweethearts invite their drastically different families on a Cape Code vacation, raising questions about marriage, intimacy, and kinship.

Who it's for: Fans of Wang's trademark wit and sly humor (see: Joan Is Okay and Chemistry); anyone with an in-law problem.

Woo Woo by Ella Baxter [F]

What it's about: A neurotic conceptual artist loses her shit in the months leading up to an exhibition that she hopes will be her big breakout, poking fun at the tropes of the "art monster" and the "woman of the verge" in one fell, stylish swoop.

Who it's for: Readers of Sheena Patel's I'm a Fan and Chris Kraus's I Love Dick; any woman who is grateful to but now also sort of begrudges Jenny Offil for introducing "art monster" into the lexicon (me). —SMS

Berlin Atomized by Julia Kornberg, tr. Jack Rockwell and Julia Kornberg [F]

What it's about: Spanning 2001 to 2034, three Jewish and downwardly mobile siblings come of age in various corners of the world against the backdrop of global crisis.

Who it's for: Fans of Catherine Lacey's Biography of X and Joshua Cohen's The Netanyahus. —SMS

Sand-Catcher by Omar Khalifah, tr. Barbara Romaine [F]

What it is: A suspenseful, dark satire of memory and nation, in which four young Palestinian journalists at a Jordanian newspaper are assigned to interview an elderly witness to the Nakba, the violent 1948 expulsion of native Palestinians from Israel—but to their surprise, the survivor doesn’t want to rehash his trauma for the media.

Who it’s for: Anyone looking insight—tinged with grim humor—into the years leading up to the present political crisis in the Middle East and the decades-long goal of Palestinian autonomy. —NodB

The Shutouts by Gabrielle Korn [F]

What it's about: In the dystopian future, mysteriously connected women fight to survive on the margins of society amid worsening climate collapse.

Who it's for: Fans of Korn's Yours for the Taking, which takes place in the same universe; readers of Becky Chambers and queer-inflected sci-fi. —SMS

What in Me Is Dark by Orlando Reade [NF]

What it's about: The enduring, evolving influence of Milton's Paradise Lost on political history—and particularly on the work of 12 revolutionary readers, including Malcom X and Hannah Arendt.

Who it's for: English majors and fans of Ryan Ruby and Sarah Bakewell—but I repeat myself. —SMS

The Afterlife Is Letting Go by Brandon Shimoda [NF]

What it's about: Shimoda researches the mass incarceration of Japanese Americans during WWII, and speaks with descendants of those imprisoned, for this essay collection about the “afterlife” of cruelty and xenophobia in the U.S.

Who it’s for: Anyone to ever visit a monument, museum, or designated site of hallowed ground where traumatic events have taken place. —NodB

No Place to Bury the Dead by Karina Sainz Borgo, tr. Elizabeth Bryer [F]

What it's about: When Angustias Romero loses both her children while fleeing a mysterious disease in her unnamed Latin American country, she finds herself in a surreal, purgatorial borderland where she's soon caught in a power struggle.

Who it's for: Fans of Maríana Enriquez and Mohsin Hamid. —SMS

The Rest Is Silence by Augusto Monterroso, tr. Aaron Kerner [F]

What it is: The author of some of the shortest, and tightest, stories in Latin American literature goes long with a metafictional skewering of literary criticism in his only novel.

Who it's for: Anyone who prefers the term "palm-of-the-hand stories" to "flash fiction." —JHM

Tali Girls by Siamak Herawi, tr. Sara Khalili [F]

What it is: An intimate, harrowing, and vital look at the lives of girls and women in an Afghan mountain village under Taliban rule, based on true stories.

Who it's for: Readers of Nadia Hashimi, Akwaeke Emezi, and Maria Stepanova. —SMS

Sun City by Tove Jansson, tr. Thomas Teal [F]

What it's about: During her travels through the U.S. in the 1970s, Jansson became interested in the retirement home as a peculiarly American institution—here, she imagines the tightly knit community within one of them.

Who it's for: Fans of Jansson's other fiction for adults, much of which explores the lives of elderly folks; anyone who watched that documentary about The Villages in Florida. —SMS

Editor's note: We're always looking to make our seasonal book previews more useful to the readers, writers, and critics they're meant to serve. Got an idea for how we can improve our coverage? Tell me about it at sophia@themillions.com.

[millions_email]

Robert Birnbaum and Darin Strauss

As is frequently the case, having met and yakked with young novelist and NYU writing mentor Darin Strauss back in 2002, on the occasion of the publication of his second novel The Real McCoy, he and I kept in touch and resumed our conversation for his 2010 memoir Half a Life.

Though, for a number of reasons, Strauss' tome is not my kind of story — the memoir recounts a profound event in his life when, as a teenager, he runs into and kills a bicyclist — as Strauss is a bright, thoughtful, and engaging conversationalist, I was pleased to talk with him again. In the course of the chat that follows, we talk about this event that has been central in his life, its aftermath, why he wrote the book, readers' responses, his own post-publication conclusions, and a wide swath of topics, literary and non-literary.

Robert Birnbaum: If I didn’t know you as a writer of three well-regarded novels, why would I want to read this book, a memoir?

Darin Strauss: Well, I think this book [Half a Life] has had more commercial appeal than my novels. I am not a fan of memoirs in general. I am a novelist and I will remain a novelist but I think this story — I should say what it’s about. I was in a car accident in high school — I was driving in the far left lane. A young girl on a bicycle on the shoulder swerved across two lanes of traffic into my car and she died.

RB: Does the sentence “I killed her” apply to this?

DS: Well, yeah. That was the thing I couldn’t say for a long time. The first sentence of the book is, ”Half of my life ago I killed a girl.” Which is something it took me 20 years to be able to say. I think she was at fault but I was driving a car and hit her and she died — it's linguistic cowardice to avoid that sentence.

RB: Saying you killed her doesn’t assess responsibility. Blame is a separate issue.

DS: Yes, I think I blamed myself in the past more than I do now. But to answer the first question, the reason I wrote the book is because of the response I got. I did something on This American Life about the accident. Which was the first time that I had done anything publicly about it. The first time I told anyone besides the people close to me was on National Public Radio. I thought I would just do a radio thing about it, but I got hundreds of emails asking me for the text saying they thought it would help them or someone they knew who was going through some sort of grief. And so I thought I should maybe do it as a book — I was always as a kid going through this wishing there was something I could read that would help me. There isn’t anything specifically for people who are survivors of these accidents. Which police call dart-out accidents. And there are 2,000 of those a year and people who are in these dart-outs, or no fault deaths as the insurance companies call them — people who are not at fault are more likely to suffer post-traumatic stress. And so, there was no book for me and so I thought I will write a book for the 18-year-old me who didn’t have the book. And the response has been amazing. Overwhelming. I got emails from people who were coming back from Iraq suffering PTS, or someone whose brother committed suicide. There’s something beneficial in reading a story about someone who is going through grief if the story is told honestly.

RB: What is the benefit?

DS: There are things that I hadn’t seen written about that I wanted to write about. The performative nature of grief — how people don’t feel sad 100% of the time but have to pretend that they do because society expects you to act a certain way. How also we have inappropriate thoughts at these moments, inappropriate actions. I hadn’t seen that written about or examined enough so I wanted to look at that. It's funny, my editor said I should cut something out of the book that was about that. The girl cut in front of my car. I hit her. She died. But as she is lying there in the street some pretty 18-year-old girls came over to me and asked me if I was okay. I can only explain it by saying I was in shock, but these girls were cute and I started flirting with them. As the bicyclist is dying in the street waiting for the ambulance. That’s something I was always embarrassed about but felt I should write about because it was one of those inappropriate moments that I think reveals something about the way we were designed not to deal with grief. But the book’s editor wanted to cut that out because it made me look too unsympathetic.

RB: Isn’t that the point?

DS: If the book is only about me trying to look sympathetic then there is no reason to write the book. I didn’t want to write an advertisement or a piece of propaganda for me. I wanted to write about the young me as I would write about a character in a novel. And look at all that person's flaws and hold them up to the light. Because I think that’s what we get out of good fiction, too. Good fiction teaches you how to live. What I turn to good fiction for is not the plot really — that’s what hooks you into the story. But it’s the observation of how people go through the world. And you learn by seeing people be imperfect and so that’s what I wanted to do. Hopefully — I didn’t set out to write a self-help book but if —

RB: Those tend not to hit their target. Are there stories that shouldn’t be told? Or needn’t be? Years ago Stephen Dixon wrote a book called Interstate, in which two infants are shot and killed in a drive-by and the father who is driving the car descends into a pit of despair. My son had just been born and I just couldn’t read past the first chapter.

DS: I remember the book — it’s the first chapter played out again and again, with different ways the father would handle it. Yeah I think there are some stories that are — but even that handled really well could be great.

RB: Even handling it well —

DS: I know what you are saying. That’s why memoirs for the most part turn me off. When memoir opens itself up to criticism it’s because it's prurient or self-aggrandizing or salacious in some way. So this was an attempt not to — I wanted to make it an anti-memoir. I was going to do the book with Penguin but I ended up doing the book with McSweeney’s —

RB: Why?

DS: I said, I don’t want to write a memoir, I just want to write about this accident and what I learned from it. And I want to do that because people responded really well to the This American Life thing. I wanted to examine it a little more deeply than I did on the radio. (I am actually embarrassed now — having written the book I think the early piece was kind of glib.) But I am not sure how long it’s going to be — it might just be 50 pages. It’s just going to be about the accident. My editor said, that’s great but it has to be 200 pages. We are happy to print it — we need for it to be a viable paperback. It’s got to be 200 pages. I said, what if the story is only 50 pages? He said, well you can pad it. I said, forget it, but then Dave Eggers contacted me or maybe it was Eli [Horowitz] — and McSweeney’s said they would publish it at 50 pages. I said, that’s great, and it ended up being 200 pages. It’s longer than I thought it would be but it's still a short book.

RB: Why are there no chapter headings or numbers or titles?

DS: I wanted it to have a disjointed feeling in the manner that you feel when you go through something like this that life comes at you in a disjointed way.

RB: Can you start anywhere in the book and move backward or forward?

DS: I don’t think so — I hope that there is an arc to it. The challenge was to — every book is a magic trick. Every realistic novel pretends to be realist but is actually a complete fabrication. The trick is to make it seem like it's not. [In] this book [it] was more difficult to do that because I wanted to remain truthful and to be respectful of the girl in the incident, but also I was very aware that I wanted it to be a good reading experience — not just to be a therapy exercise for myself. So I thought, I have to make an arc and a dramatic structure and all that but I wanted it to be less visible. And wanted it to be somewhat disjointed especially in the beginning because that’s the way we experience these things. So hopefully it was mirroring that.

RB: How firm is that border between fiction and non-fiction?

DS: Ah, I’m not a non-fiction writer for the most part, so my wife who is a journalist would laugh and say, “Are you sure you are not making things up? Are you being truthful?” So that was the real challenge — to remain absolutely faithful to the facts. I didn’t want to make anything up.

RB: Two of your novels were based on historical figures or characters —

DS: Chang and Eng, my first book, which was about two famous conjoined twins, I took a lot of liberties.

RB: I noticed you refrained from using “Siamese twins.” [laughs]

DS: Yeah, because I was corrected a lot. People from Thailand are sensitive about that. I sold the book to Thailand — it's not very often there’s an American book about Thailand. They were going to make a big deal of it and fly me out for a Thai book festival, and then they translated it [laughs] and I kept hearing from the translators that they were having a lot of problems: ”You’re making stuff up here. This is not what happened in Thailand back then.” And so I never got the invite. I took a lot of liberties with old Siam, too. I wrote that book when I was 26 and broke and couldn’t afford to fly there. So I bought a Let’s Go Thailand and used that as my research and invented stuff. Which is okay. A novelist doesn’t have to tell the truth. The beginning of Kafka’s Amerika is the Statue of Liberty holding up a big sword. There is a debate of whether he was trying to make a point or he didn’t know.

RB: Alan Furst, who rigorously researches his novels, says he doesn’t take any liberties because as he says, “a lot of blood was shed” in these stories. And beyond that readers still have unwarranted expectations —

DS: I think we talked about this four years ago [more like nine years]. There is a quote from [E.L.] Doctorow where he said, “that historical novelists should do the least amount of research they could get away with.” The key part of the sentence is what you can get away with. You don’t want to make ridiculous mistakes. You don’t want to embarrass yourself or take the reader out of the situation. But you can take liberties because it says “novel” on the book.

RB: More and more it says, “Such and Such, a novel.” And less and less do people pay attention.

DS: It’s true. Although writers go into a publisher and say “novel,” and the publisher kind of slides out into another room. I have a number of students trying to sell novels and they have been told to say it’s a memoir, it's easier to sell memoirs. But Doctorow once told me that he received a letter from someone saying, “In Arizona there aren’t X kind of cactuses which you had in your book.” He said, “There are in my Arizona, madam.” Which is a dashing way of saying he screwed up but he didn’t care.

RB: Tom Franklin [for Hell at the Breech] pointed out that readers would heckle him about armadillos and the shape of a cigarette tin.

DS: Yeah, yeah. Bellow said he was tired of being crucified on the cross of American Realism. Hopefully a novel gets to deeper truths than the shape of a Lucky Strike container. But you do want to be truthful enough — if it’s not plausible the reader will lose confidence and then the book is lost. I was just talking to someone about Zadie Smith’s On Beauty, where she apparently makes tons of mistakes about Boston geography, saying something like Harvard was in Porter Square and things like that. Which took Boston readers out of the book. I didn’t notice it because I am not from Boston. So I thought it was a great book.

RB: Who am I to say something is irresolvable. But I was reading an essay by Curtis White [The Middle Mind] and he refers to William Shawn as the publisher of the New Yorker. I didn’t think it made the rest of his remarks without value, but I wondered about what editors or fact checkers were doing.

DS: I know there are fewer and fewer fact checkers. My wife works at Newsweek and they hire younger and younger people and they have fewer and fewer people to catch mistakes at these magazines. There has been a loosening of standards across the board but that’s a different conversation.

RB: There is always Edward Jones — he spent 12 years writing The Known World, intending to research from a long list he had, and he never used that list. And he most definitely made stuff up. But I dare you to identify it.

DS: Exactly.

RB: [chuckles] Though a history professor from Texas was upset that in my various online citations of my chat with Jones I had no problem with his approach.

DS: I don’t know why people come to fiction with that expectation — that it’s going to be the same as a biography or something. And have the same standards of factualness when it’s a fairy tale — what Nabokov called his books. Peter Carey told me when he writes about his hometown he purposely puts in mistakes just to piss people off. That’s kind of funny.

RB: The other side of the coin is that you can get a certain kind of pleasure out of a book that is about a place with which you are familiar. I loved [the late lamented] Eugene Izzi, a Chicago crime story writer, or I suppose people in Boston like Robert Parker and they expect everything to be as they know it.

DS: A lot of Jon Lethem’s popularity came from taking Brooklyn as his literary subject before anyone else had, and people turned to Motherless Brooklyn — I’m from Brooklyn now so it feels his territory because he wrote about it. So there is a pleasure for natives in reading about their home turf.

RB: So we have variable valences of why we derive pleasure from reading — some are higher than others but when we talk about this stuff we are supposed to say smart things —

DS: Yeah hopefully we turn to books for the writing or the moral truths or whatever you get out of it but there is something nice about saying, “Oh I know that street.”

RB: I find I have learned more history from Gore Vidal, Edward Jones, Alan Furst, John le Carré, John Lawton, and Philip Kerr than as an undergraduate history student.

DS: I was talking to a writer friend David Lipsky. He wrote a book called Absolutely American about West Point and the book about David Foster Wallace where he traveled with him [Although Of Course You End Up Becoming Yourself] — kind of a new way of doing biography. It got good reviews, but I am not sure reviewers understood how revolutionary it could be. Even when people say the novel is in trouble and there aren’t as many readers, which people have been saying as long as there has been a novel around, I am sure more people read about the French-Russian war than read War and Peace, but nobody goes back to read the newspapers. These made-up stories are the way future generations find out about these things. I am sure more people read Libra by Delillo about [Lee Harvey] Oswald than anything else.

RB: Than the Warren Commission Report [laughs].

DS: Exactly. Or anything. If you think about it like that then we have a certain responsibility to be honest.

RB: There is a mistake about the way history is taught — the emphasis is on minutiae and not narrative — not the juicy stories about human frailty and foibles. And what do you know after you know all the details?

DS: Look at the political discourse. It seems like people know nothing.

RB: I see signs calling for the impeachment of the president. And I am sure that the sign carriers know nothing about impeachment. The House decides there is to be a trial —

DS: — based on crimes and misdemeanors. It’s not like saying we don’t like the guy. It’s like if the president is unpopular he should be impeached. The memories are so short — the Clinton impeachment was 10 years ago or so. He was impeached but not forced to leave office. I don’t what it is — there is something narcotized about this country.

RB: I look at James Howard Kunstler’s website ClusterFuck Nation and he decries the public conversation, and he recently asked, “Where did all the sensible people go who used to stand up against the kind of radical silliness that is so prevalent now?”

DS: It’s very strange. Where are the country club Republicans who were fiscally conservative but didn’t want to get rid of public education or meddle in social issues? Didn’t want to overthrow the government?

RB: Sold out? Went to ride their horsies? They supported McCain.

DS: The thing about McCain that was so weird — there’s a great McCain piece by David Foster Wallace — he was honorable enough to do the right thing —

RB: — once in his life.

DS: But in the worst circumstances. To have his fingers broken and to refuse medication — after all this torture to say, “I’m not the first in line so [other] people should go home before me." Which is the most noble thing I can imagine. And then to totally sell out, which makes me think if you can stand up to Viet Cong torture but not attack ads, it says something interesting about power.

RB: And that we are more complicated. I think in some twisted way McCain feels entitled because of his war experience. He is convinced of his own nobility and that the rest of it is just politics. And in a way it is just politics.

DS: It is just politics although he did bring Palin onto the national stage. And so if she is the next president we have him to thank.

RB: My son brought home a chart from school in which he was asked to evaluate himself in ten categories and his teacher would also. The point of the exercise was whether the world was better off with you in it. His self-score was 96 and his teacher scored him 89. They were obviously close, but the class participation was scored a 5 by the teacher. I bring this up because how we see ourselves is a fluctuating thing. And I wonder about this when I try to assign a value to a book like yours. If I understand you correctly the people who benefit from this book are people who have had a similar experience.

DS: Most people have had a similar experience — it doesn’t have to be as spectacular. Everyone carries something that they are guilty about.

RB: You’re extending the franchise of this book.

DS: I’m telling the response I have gotten. People that carry something they are guilty about around or feel a grief they don’t know how to express. It’s been more universal than I thought. Which has been nice. It’s strange for a fiction writer. If you write a novel and people email you it’s generally, I liked it or didn’t like it. Not, here’s my terrible story please tell me what you think. I was doing Philadelphia NPR, and they took callers and each call was sadder than the one before. One woman called in saying her son was killed in a car accident and she had never seen grief written about in that way and she thanked me. That was weird since I wasn’t sure that people who lost kids in car accidents were a demographic for the book. And then a guy called in whose daughter was killed in a car accident and his wife was made quadriplegic and he is taking care of his wife now and his daughter is gone. I didn’t know what to say and he asked me if he should reach out to the driver. I said, “I am only a story teller, I don’t know. If it would make you feel better I think you should.” It sounds like Dr. Phil but I didn’t know how to respond.

RB: Well, you wrote the book – need you say anymore? Or what more is there to say?

DS: I don’t think so but these kinds of books open you up to that. Right before I published I heard from A.M. Homes, who wrote a really good memoir, and she said, ”Be prepared. It's exhausting.” And Dave Eggers who edited the book with me —

RB: He has his own story.

DS: He said you have to prepare yourself. People want to talk to you in a way that they don’t with novels. In a way, it's better if they don’t meet the novelist because the novel stands as its own thing and meeting the novelist can muddy the feeling you get from the book. But if you are writing about yourself, people want to meet you and talk to you to see if you compare to the you in the book or how you are now after you have written the book. So it’s much more intimate.

RB: With the expectation that you have some expertise.

DS: Surprisingly that’s happened a lot. Maybe I just choose subjects that are arcane. My first book about twins — anytime conjoined twins are separated around the world I would get a call from some reporter asking about conjoined twins. And I would say, I’m a novelist.

RB: The world’s foremost authority —

DS: — on Siamese twins. For my third book, a novel called More Than It Hurts You about Münchausen by proxy where a mother injures a child, I was on Good Morning America talking about Münchausen’s disease with an expert. I kept saying I’m happy to go on TV but I’m no expert on this. But maybe that’s not true — Roth said one of the jobs of the novelist is to be smarter on the page than he is in real life. So I had to become an expert — at least temporarily.

RB: It does also speak to the efficacy of the so-called talking cure.

DS: That’s been one of the moving things. I kept a file with hundreds of emails now and a number of them have said, I haven’t told anyone this. I’ve never met you but I haven’t told my husband or something like that. That’s a validation of the talking cure. I had terrible experiences with therapy. Another reason I wrote the book — to figure out what I think about this. That’s the way I do it. Since I’m a writer, to understand how I see something I write it down. It’s much more effective than therapy — sitting at the computer working my way through something.

RB: People certainly organize their perceptions of the world differently — some effortlessly. To me everyday is a new day, almost like starting over again.

DS: Maybe that’s why people look for help — they don’t know how to organize their lives into stories until they see someone else do it. With this book I stumbled into therapeutic cures that I didn’t know about. Not that the book should be therapy for me. If it’s just therapy for me then I should write it and not publish it. I hope it has value beyond being cathartic for me. In this disorder called complicated grief therapy, which is a fancy way of saying people are sad, the therapy for that is that you are to talk into a tape recorder and say what makes you sad and then play it every night for 16 weeks. It sounds like torture — it’s thought to be effective because you have a tape, a physical object that you can turn off and put away. I didn’t know about it until I was researching the book. But writing the story every day and turning the computer off at night was a version of that therapy. The book is like my tape. And then talking about it to you and on the radio and to crowds at readings is like A.A. — making a public confession. So to me it was a great therapy. You said something about organizing life; my friend David Lipsky was saying anyone who teaches writing by saying you should show and not tell is going to fail. As he put it, “life is showing all the time, what literature does is tell you what that show means.” Movies are a show, life is a show. What books can do is tell in a way the others can’t.

RB: Where do these clichés come from, like “write what you know”? What do you know?

DS: Exactly. It’s bad advice for other reasons too. If you only write what you know, you will never know anything new. That’s the weird thing about our education system — right now in the Army they force you to take classes all the time as an adult. Which makes sense — why only be taught for 16 years of your life and then never be taught anything again? That’s to last you for 70 years. Why is that the method? Why wouldn’t you want to keep learning?

RB: There is some science that holds if you continue to learn that is in fact a benefit to your brain.

DS: Yeah, I read about a study that said you should try to switch things up every week just to keep your mind active without taking a course. Open doors left-handed one week and right-handed the next — just to teach yourself even in the most minor way something new to keep your brain active.

RB: When I drive to places I try to take different routes each time. I leave enough time so I may get lost or just wander around. So when will you be done with this?

DS: I was taking to Dani Shapiro who was nice enough to review the book for the Times. I didn’t know her beforehand, but I thanked her for the review and we got to talking and she was saying memoirs kind of never end. A novel is over when your next novel comes out but people still talk to her about the memoir she wrote ten years ago. Because it’s personal, and you are opening up your closet. We’re a voyeuristic society. I find most memoirs distasteful — it’s strange I ended up writing this. I thought, I will never write about this, I am a novelist. Not only that but I don’t read non-fiction a lot so I would never want to write a memoir. Something about this story was very insistent, asking to be told. I realized in writing the book that I had been writing about this all along. The girl’s parents at her funeral told me, we will never blame you — don’t worry about that. But whatever you do in life you have to live it twice as well because you are living for two people. And then they sued me for millions of dollars after that. After they said they wouldn’t blame me. The important thing from that is I took that very seriously, living for two people. I think that’s why I wrote Chang and Eng. That book deals with how we are different people at once. The end of the book — “this is the end that I have feared since we were a child.” So the “I” and the “we” means they are both one and two people. My second book was about a guy who lives in NYC and becomes an imposter and doesn’t tell anyone about his past. I had this accident in high school, went to college, and then moved to NYC and never told anyone about this. My third book is about a family from the suburbs with a secret that no one knows — I was growing up in the suburbs and had this secret, so obviously this has been informing my writing, in a way I hadn’t realized, forever. I wonder how stark a line it will draw in my fiction.

RB: Have you started the next novel?

DS: I have — I wanted something light after this. We’ll see. Writers often have this one thing they obsess about. Roth seemed to be writing the same book for a time — now he is writing obsessive books about being older. I wonder if my obsessions will change — a lot of writers have their one subject and keep writing around it, circling it. Bellow, no matter where his books were set, wrote about what it means to be a thinking person in a society where thinking people are not valued. And Updike had his pet obsessions — they seemed to be about a good boy being naughty. What does that mean? Bellow also said he didn’t want to go there because he didn’t want to know why he was writing what he was writing. Now I know and I wasn’t Bellow to begin with.

RB: Have been teaching since we last spoke?

DS: I went to Columbia as an adjunct for a while and came back when this new director of the creative writing program [of NYU] Deborah Landau, who amazingly re-energized, not even re-, she energized NYU faculty and brought in a bunch of people. I was lucky to be hired by her. She brought in Junot Díaz and Zadie Smith and Jonathan Safran Foer — she brought in this amazing constellation of people. On the poetry side she brought Anne Carson and Charles Simić. It’s an amazing place to work. I have my office there because I can’t work at home — I have three-year-old twin boys. And I go to work and it’s almost stiflingly overwhelming because you know these incredible people are doing incredible work — that’s both energizing and terrifying.

RB: Yeah.

DS: In some ways it’s beneficial to the writing — it forces you to return to first principles all the time. You have to tell students why you think something works and why it doesn’t. It gives voice to your aesthetic in a way that helps you form it. Also, it keeps you open-minded because you are reading people who have a different aesthetic. And you try to help them not by saying how you would write it yourself but try to get them to figure out how to be more successful in what they wanted to do. It can also be stultifying. It’s like when you try to walk up the stairs if you spend the day telling people, ”Well you put one foot in front of the other, and then you lift up your knee and move it forward and put the other foot down.” When you walk the stairs next you will be pretty self-conscious about it. It’s a balancing act.

RB: You use novels in your courses.

DS: In the Crafts classes — I often use books that I think are flawed. I teach Marry Me by Updike which is a good book but not his best.

RB: Glorious failures?

DS: Yeah. I wouldn’t say the book is a failure — but when you see a great writer make mistakes it can be instructive. I teach some all-out masterpieces. I shouldn’t say this but with modern academia you are also expected to have from many different — from both genders and a lot of different ethnic groups. You have to fill those slots.

RB: You feel that is an obligation? Are you conscious of it?

DS: Yes, but it’s not necessarily a bad thing — you want students from all different backgrounds to feel you are not being exclusionary. But I wouldn’t teach an author I don’t like.

RB: Right, it’s not like the choices are limited.

DS: I teach Jhumpa Lahiri and Zadie Smith. I like Zadie’s work better.

RB: I wasn’t impressed by Lahiri’s stories. I liked the film of her novel, The Namesake.

DS: Her stories are well-constructed. They are ingenious but they aren’t exciting language-wise.

RB: How well-read are your students?

DS: It varies. A lot of undergrad students are well-read, but I am often shocked at how they are not. A lot of people want to be writers who don’t care about why or how to get there. So when you come across someone who is paying a lot of money to go to grad school and one assumes they are trying to make that their life, it’s very strange to see that they haven’t read that much.

RB: Assuming it is a prerequisite of being a decent writer?

DS: Yes. It’s kind of like saying I want to be a professional baseball player but I don’t watch or practice much baseball. I just want to put on the glove and play. It’s fine if you are doing it as a social activity. When you make a commitment to be a writer then it’s strange you wouldn’t want to learn about it.

RB: Despite the warnings and evidence, your students still aspire to become writers?

DS: Yes, that’s something I feel guilty about in teaching in these programs.

RB: How many students have you had over the last ten years or so?

DS: 30 a year for nine years. Whatever that is.

RB: 270. Of those, how many have published one book?

DS: Two so far. But a lot of them were undergrads and they are not 30 yet. I think more will do that. It’s a good grad class if two or three publish.

RB: And what are the rest doing?

DS: I don’t know. That’s what’s scary about these programs. They are expensive, although NYU is good about giving money and they are working on making it free for everyone. Then I would feel less guilty about it. You can get a lot out of learning how to write and learning to be a reader.

RB: That’s one self-justification of teachers — you get better readers.

DS: Michael Thomas [Man Gone Down] tells all his students that if they are taking these courses to be writers, it’s a bad idea. This will help you become a smarter reader and if you chose to become a writer, good luck.

RB: Being a smarter reader is a great benefit.

DS: It sure is. But the issue is, is it worth the money? NYU is very competitive to get into — 30 fiction students out of about 800 are accepted.

RB: Like the Writer’s Workshop.

DS: Yeah, and once you are in that circle of fire you are expected to get somewhere. Maybe two out of 30 will publish one book and one of those two will have a career. It’s very tough.

RB: To quote Fats Waller, “One never know, do one?”

DS: [laughs]

RB: Thomas hasn’t been heard from since he won the IMPAC award in 2007.

DS: That was recently. He teaches at Hunter.

RB: That’s an interesting place. They have —

DS: — Peter Carey —

RB: — Colum McCann.

DS: A small department [Tom Sleigh and Gabriel Packard]. McCann won the National Book Award last year and Peter was nominated this year and they are both really, really good.

RB: McCann is Mr. Exuberant.

DS: He really lives up to the image of the Irish raconteur, try to go out drinking with him and you won’t make it home. A great writer. Peter, too. He was a teacher of mine at NYU. It ended up working out for me, but when students ask if should they get an MFA I never give an unqualified yes.

RB: If someone asked me I’d ask, what are the choices? Go into plastic.

DS: I did a reading with Jennifer Egan and she hasn’t gotten her [MFA] and she wondered if she missed out. It hasn’t hurt her. She is having a good career. I tell students if they need the time to write and have people read their stuff then it’s great. I was talking to someone taking a course from Oscar Hijuelos, and he was considered the worst one in the class and the teacher was hard on him saying he shouldn’t be a writer and then something switched and one day he came in with the beginning of his first book and he was great all of a sudden. There shouldn’t be anyone who is an arbiter, saying you can’t write because sometimes it takes people a while.

RB: Isn’t it the same with editors and buying books? Think of all the stories about writers who have gotten 20 to 30 rejections and then one editor says, “Yeah” and they are off.

DS: Proust had to self-publish the first volume of Remembrances of Things Past. One of the things that’s great about him is that everyone said his sentences are too long, that’s why we can’t publish him, [both laugh] so at the beginning of the second book, the sentence is one of the longest in the entire book. What a great fuck you.

RB: It’s fascinating that these literary chats are an attempt to regularize an exploding array of characters and stories. It seems like an untameable beast. As we talk here, what are we explaining or clarifying? The best stuff is maybe what we can’t explain.

DS: That’s true. Writing can be taught to a degree. The best thing it can do is save you years of self-discovery — which may not be a good thing. Maybe you should learn on your own. You can teach people tricks you have learned from reading but obviously you can’t teach talent. Maybe you can help students achieve the maximum from their talent.

RB: Talent can be overrated. There’s something to be said for perseverance.

DS: Lethem who taught at NYU said this to me once: talent was kind of meaningless. Whether you publish or write good books it’s the people who keep trying, keep trying. There’s that Malcolm Gladwell theory — which sounds kind of glib — 10,000 hours at something will make you great at it. I don’t know where that number comes from but it’s probably true. If you sit in the chair for 10,000 hours and that translates over four or five hours a day for eight years, six, seven days a week —

RB: Well, that’s from the outside, from an external observer. Our sense of that time must be indescribably different.

DS: The first 7- or 8,000 hours are fumbling around being terrible — people who are talented might not progress because they are too embarrassed to do the apprentice period. They can’t allow themselves to be bad.

RB: Or someone tells them they are crap and they believe it.

DS: Or someone tells them they are great and they believe it. You really have to get in there in those hours whatever the magic number is, and force yourself to work hard. When I was a grad student it wasn’t the most talented people who moved on — it was the people who could take their first draft and make it a second draft. For example everyone at that level can do a pretty good first draft. It’s people who listen to criticism and say, “Fuck that, I’m good enough” who don’t go on to make a good first draft into a great second draft.

RB: Writing fiction must be about delayed satisfactions — writers take five, eight, twelve years to finish a novel.

DS: The problem with Foer and Zadie Smith being as good as they are – and I think they are both really good writers and I’ve heard they are good teachers – they are dangerous examples because of their early success.

RB: Don’t try this at home, kids.

DS: Exactly.

RB: There seems to be an attitude about Foer in the literary world. Have you noticed that? Jealousy?

DS: Yeah.

RB: In addition to the normal quotient of anti-Semitism? [laughs]

DS: I ran into Jonathan Wilson, a professor of mine, and he was planning on giving talks on new takes on anti-Semitism. I asked, what was he going say? He said, “It exists.” [laughs] If there is bad feeling toward Jonathan [Foer] it's because he has outsized success. That’s hard for people to take. I’m sure a lot of the anti-Franzen griping is the same thing. You make the cover of Time and people will grumble — that’s the way it is.

RB: I remember getting into it with a writer when they retracted a review of Foer’s second novel and came up with a negative one.

DS: I hate when people retract reviews. My first book was badly reviewed in the Washington Post for what I thought were silly reasons. The reviewer didn’t like three things about the book — I named certain characters after my friends (I thanked friends in the afterword) and very minor characters had similar names. The reviewer asked, “Is he playing games or writing a serious book?” I thought, well why are those things in opposition? Second, how am I as a white male in the 20th century qualified to write about Asians in the 19th century? And third, she claimed five words I used were not in currency in the 1800s. She was wrong about that. Those words were found in Shakespeare. I was really pissed off. I was doing an interview somewhere and this reviewer who is also a novelist was there also, doing an interview. And they said such and such is here, she wants to meet you. I said that’s okay and I sneaked out the back.

RB: [laughs]

DS: And she came around and ran into me in the parking lot. She said, “Hey I am so-and-so and I gave your book a bad review.” I said, “Yeah, I remember.” She said, “I’m really sorry I kind of liked the book. I was in a bad mood and my husband is Asian, and I thought I should say something about that.” I thought it was crappy she liked the book —she was entitled to her opinion but to apologize for it was even worse.

RB: Do you write reviews?

DS: I wrote a few that I regret — not that the book was good. It’s not good karma to write negative reviews. I am going to stop doing it. I wrote a good review of Aleksandar Hemon’s The Lazarus Project, which I thought was a good book — that was fun.

RB: As I have said many times, I think book reviewing, especially in newspapers, is a degraded enterprise.

DS: [Martin] Amis has a great quote about that. He said something like, “Reviews are the only forum where the practitioner is working in the exact same mode as the art itself but generally doing it less well.” You don’t have movie critics making a movie about the subject of their reviews. So yeah, I think it’s degraded. There was a recent review of Roth where the reviewer wrote, "I never read any Roth until this book was assigned. I dismissed him without thinking about it.” This is Philip Roth, maybe the greatest living American writer. Not having read Roth, having dismissed him, shouldn’t that disqualify the reviewer?

RB: I recently reviewed the new Cynthia Ozick and according to the dust jacket it was an homage and reworking of Henry James’ The Ambassadors. I hadn’t read that book. It bothered me that other than an epigram from The Ambassadors, I had no clue of anything Jamesian. I see that quite often, that certain stories are tied to an older work. Why tell the reader — if they are familiar with the referred-to book they should recognize it and if not they should not be distracted?

DS: On Beauty is supposed to be an homage to an E.M. Forster book, which I never read. But I liked Smith’s book. It might be a way to spark your imagination. Doctorow’s Ragtime’s plot was lifted from a 19th century novella by Kleist.

RB: And you know this, how?

DS: I took a class from him and he said so.

RB: But was it on the dust jacket?

DS: No.

RB: Does it improve your enjoyment of Ragtime? What does it do for the reader if he knows?

DS: It’s a way of coming clean. Lifting plots is as old as Shakespeare but now people are so afraid of even the whiff of plagiarism they feel if they are upfront about it it's okay. It’s okay whether you own up to it or not because there are only 36 stories out there anyway, and certainly Zadie and Doctorow made something new. But I don’t know why people feel that compunction to own up to stuff. This is something that I have noticed that’s new — even novels are listing all the books used for research. But why bother, it’s a novel.

RB: Over the weekend I read a book that very much resembles [Cormac] McCarthy’s No Country for Old Men — an unstoppable psychopathic killer searching for the protagonist — even when that came to mind I wasn’t put off because the writing was crisp and propulsive. But I could already imagine reviewers taking the author to task for lack of originality.

DS: When I said there were 36 plots, that’s based on this crazy French book called The 36 Dramatic Situations — the author, Georges Polti, spent his life doing a scientific study of writing and came up with the fact that there are only 36 possible stories and there is a wide berth within those. Number 1 is revenge and number 1A is revenge, father against son. You know there is a limited scope within which to work, so what? Why not do what Shakespeare did and use famous stories? There is something energizing about having every plot and format to work with.

RB: Do you ever think about what you would have done if your writing hadn’t panned out?

DS: Oh wow! Well, when I was a kid I thought I might be a lawyer —

RB: — and then you were sued —

DS: — and then I was so turned off by the lawsuit — I wasn’t angry with the parents, they had just lost their daughter and were very vulnerable. But I was certainly angry with the lawyer — he knew they had no case and he actually screwed them over because he told them they could make millions. But they ended up getting the most nominal sum from the insurance company just to make them go away. Which they could have gotten at the outset. And so they had to take five years of legal fees out of that. So they received almost nothing. It was just awful. The police said I wasn’t at fault, five witnesses said I wasn’t at fault. He tried to say I was drunk — 10 o’clock in the morning on a Saturday. Then he tried to say that the policeman who said I wasn’t drunk, was drunk.

RB: [laughs]

DS: It was just an awful experience, dragging me through the mud. And so I thought I am not going to be a lawyer, that’s an awful thing. But I don’t know what I would have done. I don’t know that I could do anything else, so it’s hard to say.

RB: Sold insurance?

DS: I could have done something like that.

RB: A trader or speculator?

DS: That might have been more satisfying. Writing is great in so many ways — being your own boss —

RB: As Shaw said, you don’t have to dress up.

DS: Yeah, so in all the obvious ways it’s great. It is also a job where you are never not working. So I kind of envy those people who are 9 to 5.

RB: How much has your writer life changed now that you are a writer dad?

DS: A lot. The book is short —

RB: [laughs]

DS: The book is short. I started it when my kids were one — to have one-year-old twins in the house means all hands on deck.

RB: One of the challenges of journalism is to write within a word limit.

DS: Thank you so much for having me back.

RB: My pleasure.

Image credit: Robert Birnbaum

The Million Basic Plots

In 1826, the philosopher John Stuart Mill had a nervous breakdown, and one of its causes was pretty odd. “I was seriously tormented by the thought of the exhaustibility of musical combinations,” he wrote in his autobiography.

The octave consists only of five tones and two semi-tones, which can be put together in only a limited number of ways, of which but a small proportion are beautiful: most of these, it seemed to me, must have been already discovered, and there could not be room for a long succession of Mozarts and Webers, to strike out, as these had done, entirely new and surpassingly rich veins of musical beauty.

In a way, Mill was being prescient: within a hundred years, serialist composers would forge onward, like the Vikings colonizing Greenland, to combinations of semi-tones that were not conventionally beautiful. But in another way, Mill was being ridiculous: no, a contemporary composer can't use a tune that Mozart also used, unless it's a deliberate allusion, but she can certainly use a tune that Weber also used, because no one listens to Weber any more. Mill's nightmare of permutational famine would only be a real danger if any motif that any composer invented was registered permanently in some sort of giant musical database. Perhaps such a database does now exist, but no composer would be silly enough to check it. I only wish the same were true for narrative art.

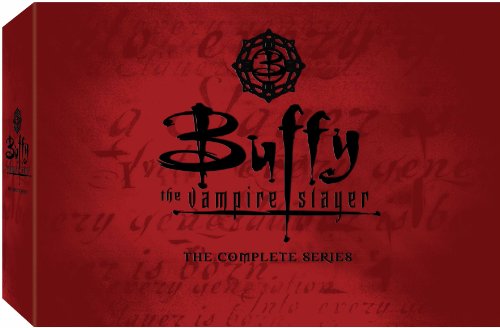

Discovering that the website TV Tropes began as a Buffy the Vampire Slayer messageboard is like discovering that Borges's "Library of Babel" began as a one-volume cricketer's almanac. Since 2004, TV Tropes has swollen into a frighteningly comprehensive taxonomy of all known plot devices across all known media. Every story that's ever thrilled you is there in microscopic cross section. In some respects it resembles books like Georges Polti's The Thirty-Six Dramatic Situations or Christopher Booker's The Seven Basic Plots, but it's not nearly so reductive: it's maximalist not minimalist, always delighted to add new categories. Really, its closest cousin is the Aarne–Thompson classification system, which attempts to anatomize all the world's folklore into about 2,500 elements. And as a writer, I find it impossible to browse TV Tropes without feeling like Mill: how will anyone ever come up with anything new?

This fear isn't abstract. Recently, I was on the point of starting my second screenplay when I thought I might as well check at the patent office for any prior art. On the TV Tropes page for Double Reverse Quadruple Agent, I came across a listing for Cypher, a 2002 film I'd never seen by Vincenzo Natali, director of the terrific Cube. The best twist in my outline was sitting there in Cypher. Dejected, I gave up on the screenplay. TV Tropes may have saved me from wasting my time on an idea that had already been wrung dry, but it may also have prevented me from developing that idea far enough that I could find something in it that was uniquely my own. So far, the same thing hasn't happened with my prose fiction, but perhaps it's only a matter of time.

Of course, this is only a problem because my writing happens to be so preoccupied with plot. Most literary fiction is inoculated against TV Tropes. When Zadie Smith updates Howard's End in On Beauty or Cynthia Ozick updates The Ambassadors in Foreign Bodies, they are assuming that the storylines are not by any means the most gripping things about those novels. I once interviewed the critic James Wood, and he told me that in his reviews he deliberately describes the entire book because he likes “destroying the tyranny of plot.” In other words, if TV Tropes gives you writer's block, then maybe you're not much of a writer.

And you can even make that same argument starting from the other side of the field. I recently asked the author China Miéville about TV Tropes, on which he has his own lengthy entry; because his work wallows in plot, I thought he might find the website as lethal as I do. In fact, he told me that he loves TV Tropes but he doesn't worry about it. You don't need a database, he said, to prove that it's almost impossible to come up with anything truly original – just riffling through the canon will do that. Your task is just to force new tricks on old dogs. (After all, both Cypher and my abandoned screenplay were basically variations on Philip K Dick. TV Tropes itself has an entry for this called Older Than They Think.) And I agree with Miéville up to a point. But a lot of the joy of his novel The City and the City, for instance, arises from its ingenious premise. If he'd read on TV Tropes that The Twilight Zone had used the same plot in 1961, he would probably still have written his book, but I find it hard to believe he wouldn't have been disappointed.

And the horrible thing is, it doesn't stop there. There's a remark somewhere by (I think) Martin Amis about how all young writers have to confront the fact that there just aren't many new ways left to describe an autumn sky or a pretty girl. It's like peak oil for lyricism. And in the age of Google Books and Amazon Search Inside, we have to confront this even more brutally. Every time I come up with a simile that feels like it might be too obvious, I can put it into the search box and find that a dozen romance novelists have used it before me.

The answer, I think, is to think more about your audience. The average reader just isn't as obsessive about precedent as the average writer. She is less likely to notice an echo, and if she does notice, she is less likely to mind. In other words, she is saner. To invent some contorted new plot twist because your previous one was already on TV Tropes, or some cumbersome new metaphor because your previous one was already on Google Books, is just self-indulgence: you like your book a bit more, but everyone else likes it a bit less. It's best to spend just enough time on TV Tropes that you're anxious to do something original, but not so long that you're paralyzed. That's easier advice to give than to follow, however, and whether or not I succeed, there is one pretty humbling circumstance I have no choice but to acknowledge: that the biggest existential challenge that I currently face as a novelist comes from a website that started life as a place for people to talk about whether Buffy should really have got together with Spike.

Previously: Trope is the New Meme

Image credit: Pexels/ana-clara-de-castro.

Tuesday New Release Day

Already on shelves ahead of its "official" release date is Mark Twain's long embargoed Autobiography. Also new this week are The Petting Zoo, a posthumously published novel by punk poet Jim Carroll; a new collection of Selected Stories from master of the form William Trevor; Cynthia Ozick's "retelling" of of Henry James’ The Ambassadors, Foreign Bodies; and, in time for election day today, Matt Taibbi's collection of biting political journalism, Griftopia.

Most Anticipated Summer Reading 2010 and Beyond: The Great 2010 Book Preview Continued

2010 has already been a strong year for fiction lovers, with new novels by the likes of Joshua Ferris, Don DeLillo, Ian McEwan, Lionel Shriver, Jennifer Egan, and David Mitchell. Meanwhile, publishing houses offered up posthumous works by Ralph Ellison, Robert Walser, and Henry Roth, and the font of Roberto Bolaño fiction continued to flow.