Mentioned in:

The Great Fall 2024 Book Preview

With the arrival of autumn comes a deluge of great books. Here you'll find a sampling of new and forthcoming titles that caught our eye here at The Millions, and that we think might catch yours, too. Some we’ve already perused in galley form; others we’re eager to devour based on their authors, plots, or subject matters. We hope your next fall read is among them.

—Sophia Stewart, editor

October

Season of the Swamp by Yuri Herrera, tr. Lisa Dillman [F]

What it is: An epic, speculative account of the 18 months that Benito Juárez spent in New Orleans in 1853-54, years before he became the first and only Indigenous president of Mexico.

Who it's for: Fans of speculative history; readers who appreciate the magic that swirls around any novel set in New Orleans. —Claire Kirch

The Black Utopians by Aaron Robertson [NF]

What it is: An exploration of Black Americans' pursuit and visions of utopia—both ideological and physical—that spans the Reconstruction era to the present day and combines history, memoir, and reportage.

Who it's for: Fans of Saidiya Hartman's Wayward Lives, Beautiful Experiments and Kristen R. Ghodsee's Everyday Utopia. —Sophia M. Stewart

The Third Realm by Karl Ove Knausgaard, tr. Martin Aitken [F]

What it is: The third installment in Knausgaard's Morning Star series, centered on the appearance of a mysterious new star in the skies above Norway.

Who it's for: Real Knausgaard heads only—The Wolves of Eternity and Morning Star are required reading for this one. —SMS

Brown Women Have Everything by Sayantani Dasgupta [NF]

What it is: Essays on the contradictions and complexities of life as an Indian woman in America, probing everything from hair to family to the joys of travel.

Who it's for: Readers of Durga Chew-Bose, Erika L. Sánchez, and Tajja Isen. —SMS

The Plot Against Native America by Bill Vaughn [F]

What it is: The first narrative history of Native American boarding schools— which aimed "civilize" Indigenous children by violently severing them from their culture— and their enduring, horrifying legacy.

Who it's for: Readers of Ned Blackhawk and Kathleen DuVal. —SMS

The Mighty Red by Louise Erdrich [F]

What it is: Erdrich's latest novel set in North Dakota's Red River Valley is a tale of the intertwined lives of ordinary people striving to survive and even thrive in their rural community, despite environmental upheavals, the 2008 financial crisis, and other obstacles.

Who it's for: Readers of cli-fi; fans of Linda LeGarde Grover and William Faulkner. —CK

The Position of Spoons by Deborah Levy [NF]

What it is: The second book from Levy in as many years, diverging from a recent streak of surrealist fiction with a collection of essays marked by exceptional observance and style.

Who it's for: Close lookers and the perennially curious. —John H. Maher

The Bog Wife by Kay Chronister [F]

What it's about: The Haddesley family has lived on the same West Virginia bog for centuries, making a supernatural bargain with the land—a generational blood sacrifice—in order to do so—until an uncovered secret changes everything.

Who it's for: Readers of Karen Russell and Jeff VanderMeer; anyone who has ever used the phrase "girl moss." —SMS

The Great When by Alan Moore [F]

What it's about: When an 18-year old book reseller comes across a copy of a book that shouldn’t exist, it threatens to upend not just an already post-war-torn London, but reality as we know it.

Who it's for: Anyone looking for a Sherlock Holmes-style mystery dipped in thaumaturgical psychedelia. —Daniella Fishman

The Message by Ta-Nehisi Coates [NF]

What it's about: One of our sharpest critical thinkers on social justice returns to nonfiction, nearly a decade after Between the World and Me, visiting Dakar, to contemplate enslavement and the Middle Passage; Columbia, S.C., as a backdrop for his thoughts on Jim Crow and book bans; and the Israeli-occupied West Bank, where he sees contemporary segregation in the treatment of Palestinians.

Who it’s for: Fans of James Baldwin, George Orwell, and Angela Y. Davis; readers of Nikole Hannah-Jones’s The 1619 Project and Isabel Wilkerson’s Caste, to name just a few engagements with national and racial identity. —Nathalie op de Beeck

Abortion by Jessica Valenti [NF]

What it is: Columnist and memoirist Valenti, who tracks pro-choice advocacy and attacks on the right to choose in her Substack, channels feminist rage into a guide for freedom of choice advocacy.

Who it’s for: Readers of Robin Marty’s The New Handbook for a Post-Roe America, #ShoutYourAbortion proponents, and followers of Jennifer Baumgartner’s [I Had an Abortion] project. —NodB

Gifted by Suzuki Suzumi, tr. Allison Markin Powell [F]

What it's about: A young sex worker in Tokyo's red-light district muses on her life and recounts her abusive mother's final days, in what is Suzuki's first novel to be translated into English.

Who it's for: Readers of Susan Boyt and Mieko Kanai; fans of moody, introspective fiction; anyone with a fraught relationship to their mother. —SMS

Childish Literature by Alejandro Zambra, tr. Megan McDowell [F]

What it is: A wide-ranging collection of stories, essays, and poems that explore childhood, fatherhood, and family.

Who it's for: Fans of dad lit (see: Lucas Mann's Attachments, Keith Gessen's Raising Raffi, Karl Ove Knausgaard's seasons quartet, et al). —SMS

Books Are Made Out of Books ed. Michael Lynn Crews [NF]

What it is: A mining of the archives of the late Cormac McCarthy with a focus on the famously tight-lipped author's literary influences.

Who it's for: Anyone whose commonplace book contains the words "arquebus," "cordillera," or "vinegaroon." —JHM

Slaveroad by John Edgar Wideman [F]

What it is: A blend of memoir, fiction, and history that charts the "slaveroad" that runs through American history, spanning the Atlantic slave trade to the criminal justice system, from the celebrated author of Brothers and Keepers.

Who it's for: Fans of Clint Smith and Ta-Nehisi Coates. —SMS

Linguaphile by Julie Sedivy [NF]

What it's about: Linguist Sedivy reflects on a life spent loving language—its beauty, its mystery, and the essential role it plays in human existence.

Who it's for: Amateur (or professional) linguists; fans of the podcast A Way with Words (me). —SMS

An Image of My Name Enters America by Lucy Ives [NF]

What it is: A collection of interrelated essays that connect moments from Ives's life to larger questions of history, identity, and national fantasy,

Who it's for: Fans of Ives, one of our weirdest and most wondrous living writers—duh; anyone with a passing interest in My Little Pony, Cold War–era musicals, or The Three Body Problem, all of which are mined here for great effect. —SMS

Women's Hotel by Daniel Lavery [F]

What it is: A novel set in 1960s New York City, about the adventures of the residents of a hotel providing housing for young women that is very much evocative of the real-life legendary Barbizon Hotel.

Who it's for: Readers of Mary McCarthy's The Group and Rona Jaffe's The Best of Everything. —CK

The World in Books by Kenneth C. Davis [NF]

What it is: A guide to 52 of the most influential works of nonfiction ever published, spanning works from Plato to Ida B. Wells, bell hooks to Barbara Ehrenreich, and Sun Tzu to Joan Didion.

Who it's for: Lovers of nonfiction looking to cover their canonical bases. —SMS

Blue Light Hours by Bruna Dantas Lobato [F]

What it's about: Through the emanating blue-glow of their computer screens, a mother and daughter, four-thousand miles apart, find solace and loneliness in their nightly Skype chats in this heartstring-pulling debut.

Who it's for: Someone who needs to be reminded to CALL YOUR MOTHER! —DF

Riding Like the Wind by Iris Jamahl Dunkle [NF]

What it is: The biography of Sanora Babb, a contemporary of John Steinbeck's whose field notes and interviews with Dust Bowl migrants Steinbeck relied upon to write The Grapes of Wrath.

Who it's for: Steinbeck fans and haters alike; readers of Kristin Hannah's The Four Winds and the New York Times Overlooked column; anyone interested in learning more about the Dust Bowl migrants who fled to California hoping for a better life. —CK

Innie Shadows by Olivia M. Coetzee [F]

What it is: a work of crime fiction set on the outskirts of Cape Town, where a community marred by violence seeks justice and connection; also the first novel to be translated from Kaaps, a dialect of Afrikaans that was until recently only a spoken language.

Who it's for: fans of sprawling, socioeconomically-attuned crime dramas a la The Wire. —SMS

Dorothy Parker in Hollywood by Gail Crowther [NF]

What it is: A history of the famous wit—and famous New Yorker—in her L.A. era, post–Algonquin Round Table and mid–Red Scare.

Who it's for: Owners of a stack of hopelessly dog-eared Joan Didion paperbacks. —JHM

The Myth of American Idealism by Noam Chomsky and Nathan J. Robinson [NF]

What it is: A potent critique of the ideology behind America's foreign interventions and its status as a global power, and an treatise on how the nation's hubristic pursuit of "spreading democracy" threatens not only the delicate balance of global peace, but the already-declining health of our planet.

Who it's for: Chomskyites; policy wonks and casual critics of American recklessness alike. —DF

Mysticism by Simon Critchley [NF]

What it is: A study of mysticism—defined as an experience, rather than religious practice—by the great British philosopher Critchley, who mines music, poetry, and literature along the way.

Who it's for: Readers of John Gray, Jorge Luis Borges, and Simone Weil. —SMS

Q&A by Adrian Tomine [NF]

What it is: The Japanese American creator of the Optic Nerve comic book series for D&Q, and of many a New Yorker cover, shares his personal history and his creative process in this illustrated unburdening.

Who it’s for: Readers of Tomine’s melancholic, sometimes cringey, and occasionally brutal collections of comics short stories including Summer Blonde, Shortcomings, and Killing and Dying. —NodB

Sonny Boy by Al Pacino [NF]

What it is: Al Pacino's memoir—end of description.

Who it's for: Cinephiles; anyone curious how he's gonna spin fumbling Diane Keaton. —SMS

Seeing Baya by Alice Kaplan [NF]

What it is: The first biography of the enigmatic and largely-forgotten Algerian artist Baya Mahieddine, who first enchanted midcentury Paris as a teenager.

Who it's for: Admirers of Leonora Carrington, Hilma af Klint, Frida Kahlo, and other belatedly-celebrated women painters. —SMS

Absolution by Jeff VanderMeer [F]

What it is: A surprise return to the Area X, the stretch of unforbidding and uncanny coastline in the hit Southern Reach trilogy.

Who it's for: Anyone who's heard this song and got the reference without Googling it. —JHM

The Four Horsemen by Nick Curtola [NF]

What it is: The much-anticipated cookbook from the team behind Brooklyn's hottest restaurant (which also happens to be co-owned by James Murphy of LCD Soundsystem).

Who it's for: Oenophiles; thirty-somethings who live in north Williamsburg (derogatory). —SMS

Seeing Further by Esther Kinsky, tr. Caroline Schmidt [F]

What it's about: An unnamed German woman embarks on the colossal task of reviving a cinema in a small Hungarian village.

Who it's for: Fans of Jenny Erpenbeck; anyone charmed by Cinema Paradiso (not derogatory!). —SMS

Ripcord by Nate Lippens [NF]

What it's about: A novel of class, sex, friendship, and queer intimacy, written in delicious prose and narrated by a gay man adrift in Milwaukee.

Who it's for: Fans of Brontez Purnell, Garth Greenwell, Alexander Chee, and Wayne Koestenbaum. —SMS

The Use of Photography by Annie Ernaux and Marc Marie, tr. Alison L. Strayer [NF]

What it's about: Ernaux's love affair with Marie, a journalist, while she was undergoing treatment for cancer, and their joint project to document their romance.

Who it's for: The Ernaux hive, obviously; readers of Sontag's On Photography and Janet Malcolm's Still Pictures. —SMS

Nora Ephron at the Movies by Ilana Kaplan [NF]

What it is: Kaplan revisits Nora Ephron's cinematic watersheds—Silkwood, Heartburn, When Harry Met Sally, You've Got Mail, and Sleepless in Seattle—in this illustrated book. Have these iconic stories, and Ephron’s humor, weathered more than 40 years?

Who it’s for: Film history buffs who don’t mind a heteronormative HEA; listeners of the Hot and Bothered podcast; your coastal grandma. —NodB

[millions_email]

The Philosophy of Translation by Damion Searls [NF]

What it is: A meditation on the act and art of translation by one of today's most acclaimed practitioners, best known for his translations of Fosse, Proust, et al.

Who it's for: Regular readers of Words Without Borders and Asymptote; professional and amateur literary translators alike. —SMS

Salvage by Dionne Brand

What it is: A penetrating reevaluation of the British literary canon and the tropes once shaped Brand's reading life and sense of self—and Brand’s first major work of nonfiction since her landmark A Map to the Door of No Return.

Who it's for: Readers of Christina Sharpe's Ordinary Notes and Elizabeth Hardwick's Seduction and Betrayal. —SMS

Masquerade by Mike Fu [F]

What it's about: Housesitting for an artist friend in present-day New York, Meadow Liu stumbles on a novel whose author shares his name—the first of many strange, haunting happenings that lead up to the mysterious disappearance of Meadow's friend.

Who it's for: fans of Ed Park and Alexander Chee. —SMS

November

The Beggar Student by Osamu Dazai, tr. Sam Bett [F]

What it is: A novella in the moody vein of Dazai’s acclaimed No Longer Human, following the 30-something “fictional” Dazai into another misadventure spawned from a hubristic spat with a high schooler.

Who it's for: Longtime readers of Dazai, or new fans who discovered the midcentury Japanese novelist via TikTok and the Bungo Stray Dogs anime. —DF

In Thrall by Jane DeLynn [F]

What it is: A landmark lesbian bildungsroman about 16-year-old Lynn's love affair with her English teacher, originally published in 1982.

Who it's for: Fans of Joanna Russ's On Strike Against God and Edmund White's A Boy's Own Story —SMS

Washita Love Child by Douglas Kent Miller [NF]

What it is: The story of Jesse Ed Davis, the Indigenous musician who became on of the most sought after guitarists of the late '60s and '70s, playing alongside B.B. King, Bob Dylan, John Lennon, and more.

Who it's for: readers of music history and/or Indigenous history; fans of Joy Harjo, who wrote the foreword. —SMS

Set My Heart on Fire by Izumi Suzuki, tr. Helen O'Horan [F]

What it is: Gritty, sexy, and wholly rock ’n’ roll, Suzuki’s first novel translated into English (following her story collection, Hit Parade of Tears) follows 20-year-old Izumi navigating life, love, and music in the underground scene in '70s Japan.

Who it's for: Fans of Meiko Kawakami, Ursula K. Le Guin, and Marlowe Granados's Happy Hour. —DF

Didion & Babitz by Lili Anolik [NF]

What it is: A dual portrait of Joan Didion and Eve Babitz, who are so often compared to—and pitted against—each other on the basis of their mutual Los Angeles milieu.

Who it's for: Fans or haters of either writer (the book is fairly pro-Babitz, often at Didion's expense); anyone who has the Lit Hub Didion tote bag. —SMS

The Endless Refrain by David Rowell [NF]

What it's about: How the rise of music streaming, demonitizing of artist revenue, and industry tendency toward nostalgia have laid waste to the musical landscape, and the future of music culture.

Who it's for: Fans of Kyle Chayka, Spence Kornhaber, and Lindsay Zoladz. —SMS

Every Arc Bends Its Radian by Sergio De La Pava [F]

What it is: A mind- and genre-bending detective story set in Cali, Colombia, that blends high-stakes suspense with rigorous philosophy.

Who it's for: Readers of Raymond Chandler, Thomas Pynchon, and Jules Verne. —SMS

Something Close to Nothing by Tom Pyun [F]

What it’s about: At the airport with his white husband Jared, awaiting a flight to Cambodia to meet the surrogate mother carrying their adoptive child-to-be, Korean American Wynn decides parenthood isn't for him, and bad behavior ensues.

Who it’s for: Pyun’s debut is calculated to cut through saccharine depictions of queer parenthood—could pair well with Torrey Peters’s Detransition, Baby. —NodB

Rosenfeld by Maya Kessler [F]

What it is: Kessler's debut—rated R for Rosenfeld—follows one Noa Simmons through the tumultuous and ultimately profound power play that is courting (and having a lot of sex with) the titular older man who soon becomes her boss.

Who it's for: Fans of Sex and the City, Raven Leilani’s Luster, and Coco Mellor’s Cleopatra and Frankenstein. —DF

Lazarus Man by Richard Price [F]

What it is: The former The Wire writer offers yet another astute chronicle of urban life, this time of an ever-changing Harlem.

Who it's for: Fans of Colson Whitehead's Crook Manifesto and Paul Murray's The Bee Sting—and, of course, The Wire. —SMS

Stranger Than Fiction by Edwin Frank [NF]

What it is: An astute curveball of a read on the development and many manifestations of the novel throughout the tumultuous 20th century.

Who it's for: Readers who look at a book's colophon before its title. —JHM

Letters to His Neighbor by Marcel Proust, tr. Lydia Davis

What it is: A collection of Proust’s tormented—and frequently hilarious—letters to his noisy neighbor which, in a diligent translation from Davis, stand the test of time.

Who it's for: Proust lovers; people who live below heavy-steppers. —DF

Context Collapse by Ryan Ruby [NF]

What it is: A self-proclaimed "poem containing a history of poetry," from ancient Greece to the Iowa Workshop, from your favorite literary critic's favorite literary critic.

Who it's for: Anyone who read and admired Ruby's titanic 2022 essay on The Waste Land; lovers of poetry looking for a challenge. —SMS

How Sondheim Can Change Your Life by Richard Schoch [NF]

What it's about: Drama professor Schoch's tribute to Stephen Sondheim and the life lessons to be gleaned from his music.

Who it's for: Sondheim heads, former theater kids, end of list. —SMS

The Serviceberry by Robin Wall Kimmerer [NF]

What it is: 2022 MacArthur fellow and botanist Kimmerer, an enrolled member of the Citizen Potawatomi Nation, (re)introduces audiences to a flowering, fruiting native plant beloved of foragers and gardeners.

Who it’s for: The restoration ecologist in your life, along with anyone who loved Braiding Sweetgrass and needs a nature-themed holiday gift. —NodB

My Heart Belongs in an Empty Big Mac Container Buried Beneath the Ocean Floor by Homeless [F]

What it is: A pseudonymous, tenderly comic novel of blue whales and Golden Arches, mental illness and recovery.

Who it's for: Anyone who finds Thomas Pynchon a bit too staid. —JHM

Yoke and Feather by Jessie van Eerden [NF]

What it's about: Van Eerden's braided essays explore the "everyday sacred" to tease out connections between ancient myth and contemporary life.

Who it's for: Readers of Courtney Zoffness's Spilt Milk and Jeanna Kadlec's Heretic. —SMS

Camp Jeff by Tova Reich [F]

What it's about: A "reeducation" center for sex pests in the Catskills, founded by one Jeffery Epstein (no, not that one), where the dual phenomena of #MeToo and therapyspeak collide.

Who it's for: Fans of Philip Roth and Nathan Englander; cancel culture skeptics. —SMS

Selected Amazon Reviews by Kevin Killian [NF]

What it is: A collection of 16 years of Killian’s funniest, wittiest, and most poetic Amazon reviews, the sheer number of which helped him earn the rarefied “Top 100” and “Hall of Fame” status on the site.

Who it's for: Fans of Wayne Koestenbaum and Dodie Bellamy, who wrote introduction and afterword, respectively; people who actually leave Amazon reviews. —DF

Cher by Cher [NF]

What it is: The first in a two-volume memoir, telling the story of Cher's early life and ascendent career as only she can tell it.

Who it's for: Anyone looking to fill the My Name Is Barbra–sized hole in their heart, or looking for something to tide them over until the Liza memoir drops. —SMS

The City and Its Uncertain Walls by Haruki Murakami, tr. Philip Gabriel [F]

What it is: Murakami’s first novel in over six years returns to the high-walled city from his 1985 story "Hard-Boiled Wonderland and the End of the World" with one man's search for his lost love—and, simultaneously, an ode to libraries and literature itself.

Who it's for: Murakami fans who have long awaited his return to fiction. —DF

American Bulk by Emily Mester [NF]

What it's about: Reflecting on what it means to "live life to the fullest," Mester explores the cultural and personal impacts of America’s culture of overconsumption, from Costco hauls to hoarding to diet culture—oh my!

Who it's for: Lovers of sustainability; haters of excess; skeptics of the title essay of Becca Rothfeld's All Things Are Too Small. —DF

The Icon and the Idealist by Stephanie Gorton [NF]

What it is: A compelling look at the rivalry between Margaret Sanger, of Planned Parenthood fame, and Mary Ware Dennett, who each held radically different visions for the future of birth control.

Who it's for: Readers of Amy Sohn's The Man Who Hated Women and Katherine Turk's The Women of NOW; anyone interested in the history of reproductive rights. —SMS

December

Rental House by Weike Wang [F]

What it's about: Married college sweethearts invite their drastically different families on a Cape Code vacation, raising questions about marriage, intimacy, and kinship.

Who it's for: Fans of Wang's trademark wit and sly humor (see: Joan Is Okay and Chemistry); anyone with an in-law problem.

Woo Woo by Ella Baxter [F]

What it's about: A neurotic conceptual artist loses her shit in the months leading up to an exhibition that she hopes will be her big breakout, poking fun at the tropes of the "art monster" and the "woman of the verge" in one fell, stylish swoop.

Who it's for: Readers of Sheena Patel's I'm a Fan and Chris Kraus's I Love Dick; any woman who is grateful to but now also sort of begrudges Jenny Offil for introducing "art monster" into the lexicon (me). —SMS

Berlin Atomized by Julia Kornberg, tr. Jack Rockwell and Julia Kornberg [F]

What it's about: Spanning 2001 to 2034, three Jewish and downwardly mobile siblings come of age in various corners of the world against the backdrop of global crisis.

Who it's for: Fans of Catherine Lacey's Biography of X and Joshua Cohen's The Netanyahus. —SMS

Sand-Catcher by Omar Khalifah, tr. Barbara Romaine [F]

What it is: A suspenseful, dark satire of memory and nation, in which four young Palestinian journalists at a Jordanian newspaper are assigned to interview an elderly witness to the Nakba, the violent 1948 expulsion of native Palestinians from Israel—but to their surprise, the survivor doesn’t want to rehash his trauma for the media.

Who it’s for: Anyone looking insight—tinged with grim humor—into the years leading up to the present political crisis in the Middle East and the decades-long goal of Palestinian autonomy. —NodB

The Shutouts by Gabrielle Korn [F]

What it's about: In the dystopian future, mysteriously connected women fight to survive on the margins of society amid worsening climate collapse.

Who it's for: Fans of Korn's Yours for the Taking, which takes place in the same universe; readers of Becky Chambers and queer-inflected sci-fi. —SMS

What in Me Is Dark by Orlando Reade [NF]

What it's about: The enduring, evolving influence of Milton's Paradise Lost on political history—and particularly on the work of 12 revolutionary readers, including Malcom X and Hannah Arendt.

Who it's for: English majors and fans of Ryan Ruby and Sarah Bakewell—but I repeat myself. —SMS

The Afterlife Is Letting Go by Brandon Shimoda [NF]

What it's about: Shimoda researches the mass incarceration of Japanese Americans during WWII, and speaks with descendants of those imprisoned, for this essay collection about the “afterlife” of cruelty and xenophobia in the U.S.

Who it’s for: Anyone to ever visit a monument, museum, or designated site of hallowed ground where traumatic events have taken place. —NodB

No Place to Bury the Dead by Karina Sainz Borgo, tr. Elizabeth Bryer [F]

What it's about: When Angustias Romero loses both her children while fleeing a mysterious disease in her unnamed Latin American country, she finds herself in a surreal, purgatorial borderland where she's soon caught in a power struggle.

Who it's for: Fans of Maríana Enriquez and Mohsin Hamid. —SMS

The Rest Is Silence by Augusto Monterroso, tr. Aaron Kerner [F]

What it is: The author of some of the shortest, and tightest, stories in Latin American literature goes long with a metafictional skewering of literary criticism in his only novel.

Who it's for: Anyone who prefers the term "palm-of-the-hand stories" to "flash fiction." —JHM

Tali Girls by Siamak Herawi, tr. Sara Khalili [F]

What it is: An intimate, harrowing, and vital look at the lives of girls and women in an Afghan mountain village under Taliban rule, based on true stories.

Who it's for: Readers of Nadia Hashimi, Akwaeke Emezi, and Maria Stepanova. —SMS

Sun City by Tove Jansson, tr. Thomas Teal [F]

What it's about: During her travels through the U.S. in the 1970s, Jansson became interested in the retirement home as a peculiarly American institution—here, she imagines the tightly knit community within one of them.

Who it's for: Fans of Jansson's other fiction for adults, much of which explores the lives of elderly folks; anyone who watched that documentary about The Villages in Florida. —SMS

Editor's note: We're always looking to make our seasonal book previews more useful to the readers, writers, and critics they're meant to serve. Got an idea for how we can improve our coverage? Tell me about it at sophia@themillions.com.

[millions_email]

Joe Sacco Grapples with Human Nature: The Millions Interview

The following interview with Joe Sacco, the comics journalist best-known for his accounts of the war in Bosnia and life in the Palestinian territories, could be called “How to Draw an Atrocity.” His work is layered in well-earned details. Safe Area: Goražde depicts a besieged town sealed off from the world by the Balkan conflict. In the midst of a civil war, one young woman asks Sacco to get her some nice jeans from Sarajevo. In what is so far his magnum opus, Footnotes in Gaza, Sacco researched a forgotten massacre of Palestinian civilians during the Suez War in 1956. There is no photographic evidence of the massacre, and so Sacco was left illustrating the testimonies of older Palestinians, filling in the physical details based on his frequent trips to the Middle East's Soweto. It’s not clear if he broke any unwritten rules concerning the way an atrocity should be depicted. He may be inventing rules of his own.

In his new collection of short pieces, Journalism, he chronicles poverty in rural India, the training of Iraqi security forces, and the recent wave of African immigration to Sacco’s native Malta. (Sacco was born in Malta and remains a citizen of the island nation, but he spent his childhood in Australia and the U.S. and has mostly lived here for about 40 years.) I met Sacco on an August afternoon in his studio in his house in Portland. We began by discussing one of the stories in Journalism, “Trauma on Loan,” about two ordinary Iraqis who were tortured by American soldiers during the early days of the Iraq War. I pointed to one moment in the piece in which Sacco illustrates the story of one of the Iraqis with a point-of-view shot from the perspective of an American soldier.

The Millions: This is something that’s very hard to do in prose journalism. If a victim is telling a story it’s very hard to see it from the point of view of the victimizer. But you, as a comics journalist, can create something like this image.

Joe Sacco: The whole point is to be able to recreate things from different perspectives. I have to give myself that freedom. I’ve always said drawing is a subjective act. Does that absolve me from an accusation of manipulation? Perhaps not in some people’s eyes. You could tone it down, I guess. I could have drawn it in a different way. That’s true. But I chose to draw it this way.

The words themselves are accurate quotes. It says, “One of the detainees was in front. His actions were like a dog’s.” I’m not going to draw a guy who’s just surly, holding back…I have a dog. And the way a dog acts, it begs and is excited. I’m just trying to visualize that.

TM: In your last Comics Journal interview you said that there has always been a grotesque quality in your work. There is some sense of the grotesque, of the strange, of the uncanny in your figures, even though you have this very journalistic desire to show something that’s real. How does this problem manifest itself when you are drawing sympathetic people like these two [Iraqi] gentlemen and this less-than-sympathetic American soldier?

JS: When I’ve said that I’ve tended toward the grotesque…what [I’m] saying is that I can never draw as beautifully as Craig Thompson (Habibi, Blankets). It’s just not in my hand. Even people who look good in real life never look good the way I draw them, not through any desire to make them grotesque but through a certain inability. I just don’t draw beautiful people beautifully. I would rather draw a good-looking woman as a good-looking woman, but I don’t have quite that ability to get it right. So my stuff tends in that direction anyway.

If I’m going to draw some American soldiers taunting an Iraqi prisoner, I’m not going to make their expressions neutral. If you’re taunting someone, you’re taunting someone. And if you’re getting a kick out of it, you’re getting a kick out of it. The action itself is grotesque. The action of doing that is grotesque. And so that’s reflected in the drawing.

TM: There’s a claim that a good novelist has sympathy for all of his characters. [Do you have any such sympathy] when you draw these bullies?

JS: No. Not always. When you’re drawing you have a lot of characters who don’t have speaking parts. A novelist generally deals with a set amount of characters. And you can flesh those characters out. But [when] a novelist is describing getting on a train with a hundred people…[he or she’s] not fleshing out all of those characters. I have to draw them. So it presents a problem.

I have a difficult time drawing the eyes of people when they’re committing atrocious acts. It’s not like I don’t do it if I’m sure they’re sadistic. In this case I probably could have done it. Because in this case, [with] a soldier taunting someone, I can imagine their sadism and I can understand a sadist’s face, or I have the pretense of thinking I can understand a sadist’s face…

Think of it as acting. Think of it as [being] a film director, because, ultimately, that’s what you’re doing. You’re saying to yourself, “How is this person going to be looking if you’re an actor?” And every time you draw something, much like acting, you have to get into the role on some level of what that person is thinking or feeling. It’s easier to draw a sadist. The more difficult thing is to draw ordinary people doing atrocious things. Someone throwing a cigarette to taunt someone is a sadist. Or anyway that’s a sadistic act. And maybe that person isn’t always a sadist. [But] I’m going to draw a sadistic expression.

I had more trouble in the book Footnotes in Gaza with this sort of thing because I didn’t think all those people [Israeli soldiers] were sadists. I think there were sadists among them. But to me, this is a case, generally speaking, of ordinary human beings killing other human beings and perhaps not even out of a sense of hatred.

I couldn’t understand the psychology of doing what they were doing. As I was drawing I didn’t draw their faces exactly because I didn’t want to presuppose their intentions or their psychological state, which is why I very seldom [draw] their eyes.

Doing [Footnotes in Gaza] in particular is when I realized I didn’t understand how to draw certain things because I didn’t understand the psychology of the moment. It’s easier to understand fear. I can draw fear. I can draw sadism. But an ordinary person doing something like this is a very difficult thing to understand. I’m not going to pretend I understand it. It was easier to hide the face.

TM: But when you are giving this level of individuality to these Israeli soldiers, these Serbian genocidal killers, these American soldiers, does that allow you to imagine a kind of individual intelligence behind them that you just described to me?

JS: I think about it all the time. I think, “This one’s gesture is going to be more aggressive. This one’s going to be aggressive but not as aggressive.” …There’s a range. Not all of them are the same. They’re not all going to behave the same way. But then you think, “Well their officers are there and they’re being told to do this. Are they going to do it?” There might be a moment too when you’re doing it and these people [victims] might be sniveling and crawling in front of you and it helps you, because they’re humiliating themselves which makes you despise them. These are things I think about. But they’re not necessarily things I understand. I’m going off in a different direction with my new work because of these very questions.

TM: What’s this new direction?

JS: I’m interested in psychology and neuroscience and understanding human nature. It [came from] the problems I had doing this [Footnotes in Gaza]…With journalism I can explain [events]. I can even explain the history behind [them]. What I couldn’t explain to myself is the individual relationship to those events. That’s why I’m telling you I had a hard time drawing this stuff.

TM: What are you working on now that is dealing with this new direction? I don’t know if you’re comfortable announcing a new project.

JS: It’s hard to describe what I’m trying to do. I want to grapple with the concept of human nature, how we develop societies, our relationship to authority, starting from the primate level on. [It] sounds like a huge huge undertaking and it is and I don’t know if I’ll be able to figure it out. I don’t know if it will make for good comics necessarily. I just want to concentrate on this story about Mesopotamia and the development of the first cities -- even before the first cities -- of how hierarchy developed, how central authority developed, how our role as people under central authority, this relationship, developed. It all interests me. That is enough. And that could go on for years. And I’ve been interviewing archaeologists in different places…

TM: Your books are very easy to read. And many of your contemporaries have moved to making comics difficult. Art Spiegelman, when he made his book about 9/11, In the Shadow of No Towers, designed the format so you don’t know where your eye is supposed to go at any given point. Chris Ware does that a lot as well. You have a linear method. When I read your books I usually feel I know where my eye is supposed to go.

JS: Well if you don’t it’s very intentional. There are cases where you are supposed to be a little confused about how to read things.

TM: Did your journalism training make you think you had to make your work as clear as possible?

JS: I think so. I think that’s it. Journalism is a constraint, on some level. I don’t even like drawing representational-y very much. I don’t think I’m particularly good at it to be honest. It never feels completely comfortable. And I’m not even sure if I drew in a cartoon-y fashion if that would be comfortable.

This is not your New York Times kind of journalism which is often really boring. The difference between reading the standard New York Times writer -- there are some exceptions -- and someone like Robert Fisk of The Independent is like night and day. I feel like I’m there with Fisk, you know. That’s the tradition I’m more interested in journalistically speaking. Yes, I want the situation to be [as] clear as much as possible because I also think often the subject matter itself is difficult for people. It’s not pleasant. I don’t need tricks. I don’t want tricks. It’s mostly pretty standard. You’ll see in my first journalistic work Palestine that there were a lot of different angles and all that. That was fun to draw, [but] it didn’t necessarily help the story along.

TM: I was thinking about the power of the short form versus the long form. I found Footnotes in Gaza impossible to read in one sitting. I felt reading it that there was a circularity to the narrative in which we kept returning to the same problem and that [this circularity] is reflective of the subject matter. So when you see the atrocities in Footnotes in Gaza they stop having the same shock after awhile. But with something like this, “The War Crimes Trials,” which is a total of six pages, there are just these few panels that have, for me at least, far greater shock.

JS: To me that’s very subjective because I’ve heard many people say very different things about Footnotes in Gaza from what you just said as far as its power to shock them. But I’m not even sure that I’m going for shock. I’m just trying to represent things in a way, even in a dull way somehow. I’m not Joe Kubert, may he rest in peace. I’m not going to draw everything spectacularly with explosions and people flying though they look like they’re in a ballet somehow. That’s not how I think of things.

If you look at the scene that you’re pointing to, maybe some of its power comes from the fact that you’re not seeing anyone getting his testicle bitten off. You have to imagine what it’s like. Would it have been more shocking if I had shown it? Maybe on some level. But it would have been cheaper and not as effective. You can be shocking and also not be effective.

TM: When you have to draw these horrors, does it affect other elements of your life?

I was miserable. And I don’t want to do it again, really. There are reasons for going off and doing other projects that aren’t journalistic in the way I’ve done them before. Partly I want to learn something new. I feel like I’ve gone about as far as I can go looking at these sorts of incidents. Which aren’t the same incidents. They’re very different kinds of things. But when you’re involved in [them] they begin to look the same. That’s one of the reasons in that Journalism book I tried to do something different than massacres. I wanted to do [things] about human migration or poverty. And even those are tough things to do. But they’re physically not as hard as drawing dead bodies over and over.

TM: I don’t know if you’ve been told this but you don’t have an identifiable accent. I would have no idea where you’re from unless I was told you were from Malta. It’s not clearly American. It’s not clearly Australian. It’s not clearly anything. Now you mention that you feel some responsibility as a Maltese citizen when you write about the plight of African immigrants in Malta. And that you feel some responsibility if not as an American citizen than as an American taxpayer for the American government’s support of Israel’s actions in the Palestinian territories. But in some ways -- I don’t know if this is insulting -- you are a man without a country.

JS: Why is that insulting?

TM: I don’t know. I’m telling you that in some way you have no fixed background. I don’t know if that helps you when you travel.

JS: Culturally, I feel more American than [anything else]. This is where I spent a lot of my time. I also have a cultural upbringing that is Maltese. So I’m not going to shake either of those things. Nor do I want to. You are who you are. I’m relatively comfortable with who I am. I don’t feel vested in any particular nationality or in any national project. I live here because I live here and I’m comfortable here. I like being here and there are things I like about living in the United States. But I don’t feel I owe anything to the United States, or to Malta or to Europe or Australia. I might feel more responsibility based on where I am for what the United States does or what happens in Malta on some level.

[As for] Bosnia...I don’t think I have a dog in any fight, in a certain way. But I certainly don’t have a dog in that fight. It’s just humans and other humans.

This transcript represents selections from a 90-minute interview. Special thanks to Eric Reynolds of Fantagraphics for assisting in this interview's preparation.

The Politics of Art: Middle Eastern Women in Fiction and Film

The four-and-one-half-hour evening train ride from Ann Arbor, Mich., to Chicago marks the beginning of my occasional, brief getaways. I've devised my own routine: as soon as the conductor checks my ticket, I head to the food car to pick up a small bottle of Cabernet and a frozen pizza -- something I'd hardly eat if it were elsewhere -- to accompany the film I've already picked out. One time, the film I had chosen was The Stoning of Soraya M. It describes the real story of an Iranian woman named Soraya, who is stoned to death as required by the rules of Shari'a, when she is (wrongfully) accused by her husband of having committed adultery. It is a powerful and moving film -- less because of its cinematography, and more due to the plot.

As I watched, I could tell that the woman sitting next to me was taking sneak peaks at the film every now and then. When I finished, she told me that she found the film to be really interesting, and asked me what the title is. At times like this, I find myself caught in a dilemma -- a feeling I suspect many Middle Eastern women get. On the one hand, I too am enraged and have my feminist blood boil at how cruel certain Middle Eastern practices can be toward women. Yet, on the other hand, I worry about the tendency that people may have of succumbing all too easily to culture blaming, perceiving these practices as abstract and independent of historical and global relations. I struggle with the fine balance of condemning violations of human rights without accidentally submitting to contemporary extensions of Orientalism.

I was reminded of this dilemma during Nobel Laureate Tawakkol Karman's speech at the University of Michigan on Nov. 14. Karman is a Yemeni feminist activist who played active roles before and during the Yemeni uprising, considered part of the Arab Spring. Throughout her speech, you could see Karman’s determination to bring democracy and gender equality to Yemen emanating from her whole being. She touched upon issues like how, during President Ali Abdullah Saleh’s rule, women were trapped in their homes under the veil of religion; whereas now, they were out on the streets, not only taking part, but leading the revolution in many aspects.

In popular culture, Middle Eastern women are rarely depicted as such -- willful and agentic. Instead, we see them as a category, rather than individuals, that is surrounded by inhuman (male) oppression. We often receive depictions of Middle Eastern women as submissive and helpless, forced to hide their bodies, and we hardly ever discuss their determination as individuals. Indeed, as Turkish writer Elif Şafak mentions in her TED Talk of July 2010, when Middle Eastern women in literature do not fit these descriptions, they are found not to be “Middle Eastern enough.” Thus, it might surprise some that Karman, who stood strong as she chanted her slogans of peace to the auditorium, with her hands forcefully shooting high up in the air, still chooses to wear the headscarf.

Craig Thompson's latest graphic novel Habibi, and Denis Villeneuve's 2010 film Incendies are two recent narratives that I’ve very much enjoyed, which endorse counter-stereotypical portrayals for their respective Middle Eastern female protagonists, Dodola and Nawal. Both Dodola and Nawal are illustrated as determined individuals, who survive through hardships unimaginable to most of us. And while both women are strong, at a closer glance, there are subtle differences in terms of the perspectives these two depictions provide on Middle Eastern women. This is seen most vividly in the relationships the two women have with their own bodies.

Thompson's Habibi takes place in a country named Wanatolia (a somewhat cheesy play on the word Anatolia). Wanatolia is portrayed as a timeless Middle Eastern country characterized by a water crisis surrounding a spectacular dam, with contrasting skylines of modern skyscrapers and neglected shantytowns, ruled by its insatiable sultan, constantly on the lookout for new gems to be added to his harem.

Dodola is one of the women kidnapped by the sultan's guards for the harem. Being part of the harem means giving up ownership of one's own body, readying it for service of the sultan's lustful urges; whenever and wherever they may emerge. In contrast to the plump and outright unattractive sultan, Dodola is beautiful and skinny. Yet, in spite of how attractive she may seem to others, Dodola feels a strong disconnect with her own body. This feeling of disconnect is further enhanced when she's impregnated by the sultan with the heir of Wanatolia, and as her body begins to accumulate fat. While it seems here that Thompson has yielded to the contemporary pressures of the slim and tender female body image, there is many a reason for Dodola to feel a disconnect with her body. As a nine-year-old girl, Dodola is sold into marriage by her parents, in order to survive the drought. And at 12, her husband is murdered by thieves, and Dodola is sold into slavery.

Thus, Dodola’s body is portrayed as a commodity throughout most of the novel. Even when she and Zam, the 3-year-old boy she rescues from the slave market, attain freedom and start a new life on a boat they find lodged in the middle of the desert (an allusion to Noah’s Ark), Dodola has to sell her body in order to gain advantage to steal food from caravans passing by -- the cliché of the woman as the seductress who uses her body as an object to manipulate men into getting what she wants. It's not long before her violent methods of seduction turn her into the legendary devil woman of the desert, sucking the life out of men through their penises, and leading "an army of jinn." Her myth is so robust that even the sultan of Wanatolia believes that her magical powers are the solution to his boredom. The exoticization of Dodola as such is reminiscent of the portrayals of Middle Eastern women in old Orientalist art and texts. So, although Thompson, on the surface, illustrates Dodola as a strong and determined character who overcomes challenges like poverty, illness, and rape, he can't seem to escape the pitfalls of these age-old, sexist stereotypes. Indeed, the legend of Dodola reaches many men in Wanatolia, one of whom eventually rapes Dodola in the desert. Thus, Dodola is rendered helpless even in one of the rare situations where she is using her own body at her own will, for her own benefit.

Incendies also takes place in a fictional Middle Eastern country. The film opens with the panoramic view of a desolate land, ornate with scarce palm trees extending tall into the sky, resembling the Arabic letter alif -- a reminder of death as a path from earth up to heaven. As the camera scans the landscape, Radiohead’s “You and Whose Army?” fades in, and we are zoomed in through the window of one of the classrooms of a torn down and abandoned school building. The song is blasting now, and we are shown a group of adolescent boys whose heads are being shaved by a couple of men who look like guerilla fighters. Later on, we can infer that the boys are being prepped as militants to fight in the streets during what seems like a civil war, to kill other boys who look just like them. And one of them, the boy with the three black dots tattooed to his foot, is political activist Nawal Marwan's long-lost son, Abou Tarek, the famous torturer of Kfar Rayat, a prison for political criminals.

Like Dodola, Nawal is made to forfeit ownership of her own body quite frequently. Early in the film, when Nawal is young, her lover is murdered by her male relatives, the reason being that a Muslim man cannot be suitable to marry Nawal, who is Christian. Nawal, a disgrace to the family's honor, is forced to give up her illegitimate love child, who will later be known as the aforementioned Abou Tarek, and whom she promises to find one day and love forever. Thus, Nawal's body is similarly portrayed as a commodity, just like that of Dodola's. Nawal's body is owned collectively, is an important determinant of things like honor and reputation for her family, and therefore decisions regarding her body are too important to be given by her. Yet, throughout the film, we see Nawal losing and regaining volition over decisions regarding her body. For instance, Nawal chooses to become politically involved in the civil war, and by disguising herself as a tutor to a nationalist general’s son, attempts the assassination of the general. This is not a very typical portrayal of Middle Eastern women, and demonstrates the urge in Nawal to take charge and make a change. As a result, however, she is sent to Kfar Rayat, where she is regularly tortured and raped. Thus, her body is once again violated, to the extent that she becomes pregnant by her torturer, Abou Tarek, and is prevented from causing a miscarriage. Thus, Nawal becomes pregnant with twins by her long-lost son, neither of them being aware of the situation.

There are many parallels between Dodola's and Nawal's stories of struggle. Both are kept in prison cells almost too small to allow them to stand for extended periods of time, suffering leisurely rapes by men, yet unwilling to give up. Both survive the pains of being separated from their loved ones, and both are reunited with them as a result of their strength and determination. What differentiates Nawal's portrayal from that of Dodola's is the way Nawal refuses to give up ownership of her body, and accepts its legacy no matter what. At the end of Incendies, Nawal's twin children, as asked of them in her will, deliver to Abou Tarek the two letters from her: one written to her torturer/rapist, and the other to her son. Thus, Nawal accepts her baby, despite her devastation at what he has become, and keeps the promise she gave him when he was born, in contrast to Dodola who feels that the sultan's baby growing inside her has taken over her body, pulling on her ribs mercilessly. In contrast to Dodola, who was not saddened by the death of her baby nearly as much as her servant was, Nawal manages to separate the rapist from the son, condemning one while embracing the other, and owns her body in an oblique way. Dodola, however, submits to male domination over her body.

Some have blamed both Villeneuve and Thompson for perpetuating stereotypical beliefs of the Middle East as being composed of war- and poverty-stricken nations, rich with male oppression and crudeness, by setting their stories in the Middle East rather than anywhere else. In Incendies, Nawal’s homeland is never named, and cities are given novel names. Yet, many have thought that parts of the plot bear a strong resemblance to Lebanon’s history, particularly to the Israeli occupation of the 1980s, and there are many similarities between Nawal’s story and Lebanese activist Soha Bechara’s life. These resemblances strike me as reminders of how blurred the line is between reality and fiction. Such an idea lends authority to the abovementioned criticisms -- that the depicted events, or ones very similar, could have easily happened elsewhere. It’s difficult not to agree with these criticisms, in light of how easily these stereotyped incidents become essentialized parts of particular cultures, threatening them with further stigmatization. The outcome of Thompson's well-intentioned depiction of Dodola demonstrates the importance of being mindful of these issues in literature, as in any other medium. However, I also agree with Azar Nafisi, who quotes Adorno saying, “the highest form of morality is to not feel at home in one’s own home.” I find there to be value in being uncomfortable about certain things that go on in your own part of the world, and being comfortable with bringing them forth to a global community for discussion. So, that day on the train, I decided to give my copy of The Stoning of Soraya M. to the curious woman sitting next to me.

The Alternative, The Underground, The Oh-Yes-That-One List of Favorite Books of 2011

While sending out calls for contributors, one writer responded to my email with the observation that these lists “seem to be the new fashion.” True. In the past few weeks, on Twitter and Facebook and wherever else I went to play hooky, these lists -- 100 Notable Books, 10 Best Novels of 2011, 5 Cookbooks Our Editors Loved, etcetera -- were lying in wait, or rather, Tumblr-ing all over the place. Of course, as an eternal sucker for the dangled promise of a good book, I had to read this one, to see what was on offer, and that one, to get it out of the way, and oh yes that one, because . . . just because. I’m not complaining, far from it. I’m just establishing that I have read a lot of these lists, in only the past few weeks, and shared them myself on Facebook and Twitter, usually at times when I should have been working; and now, since I am sick and tired of being sick and tired of seeing the same books on list after list after list, lists drawn up by respected, respectable folks in the same circles of influence, I have reached out to a band of fresh voices (some new, some established, some you know, some you will soon) and compiled the alternative, the underground, the “oh-yes-that-one” list of favorite books of 2011.

Faith Adiele, author of Meeting Faith: The Forest Journals of a Black Buddhist Nun: When Precious Williams was three months old, her neglectful, affluent Nigerian mother placed her with elderly, white foster parents in a racist, working-class neighborhood in West Sussex, England. Precious: A True Story by Precious Williams tells this wrenching story. I kept reading for the clean, wry, angry prose. Zong! by M. NourbeSe Philip is a brilliant example of how poetry can resurrect history and memory. In 1781, the captain of the slave ship Zong ordered 150 Africans thrown overboard so the ship’s owners could collect the insurance money. Philip excavates the court transcript from the resulting legal case -- the only account of the massacre -- and fractures it into cries, moans, and chants cascading down the page. I was tempted to recommend Ngũgĩ wa Thiong’o’s Dreams in a Time of War: A Childhood Memoir, since it came out in 2011. It does a lovely job capturing Kenya on the verge of independence, but read side by side, Wizard of the Crow demands attention. A sprawling, corrosive satire about a corrupt African despot, filled with so-called magical realism, African-style. Deogratias: A Tale of Rwanda by Jean-Philippe Stassen. Rwanda-based Belgian expat Stassen employs beautifully drawn and colored panels to tell the tragic story of Deogratias, a Hutu boy attracted to two Tutsi sisters on the eve of the genocide. After the atrocities Deogratias becomes a dog, who narrates the tale.

Doreen Baingana, author of Tropical Fish: Broken Glass by Alain Mabanckou is, despite its misogynistic tendencies in parts, a brilliant book. A biting satire about desperate conditions and characters who hang out at a slum bar called Credit Gone West, it should make you cry, but you can’t help but laugh bitterly.

Lauren Beukes, author of Zoo City: If a novel is a pint, short stories are like shooters: they don’t last long, but the good ones hit you hard and linger in your chest after. I loved African Delights by Siphiwo Mahala, a wonderful collection of township stories loosely inspired by Can Themba’s Sofiatown classic “The Suit.” In novels, Patrick DeWitt’s wry western, The Sisters Brothers, was fantastic, but I think my favorite book of the year was Patrick Ness’ beautiful and wrenching A Monster Calls, a fable about death and what stories mean in the world.

Margaret Busby, chair of the fiction judges for the 2011 OCM Bocas Prize for Caribbean Literature: White Egrets by Derek Walcott is a superb collection of poetry. Using beautiful cadences and evocative, sometimes startling images, Walcott explores bereavement and grief and being at a stage of life where the contemplation of one’s own death is inevitable. How to Escape a Leper Colony by Tiphanie Yanique is a very accomplished collection that delivers thought-provoking themes, nuanced and vibrant writing, an impressive emotional range and a good grasp of the oral as well as the literary. Also I would mention Migritude by Shailja Patel. Patel’s encounters with the diaspora of her cultural identities -- as a South-Asian woman brought up in Kenya, an Indian student in England, a woman of color in the USA -- give this book a vibrant poignancy. “Art is a migrant,” she says, “it travels from the vision of the artist to the eye, ear, mind and heart of the listener.”

Nana Ayebia Clarke, founder of Ayebia Clarke Publishing: Deservingly selected as overall winner of the 2011 Commonwealth Best Book Prize, The Memory of Love by Aminatta Forna tackles the difficult subject of war and its damaging psychological impact. Set in Sierra Leone in the aftermath of the civil war, Forna’s narrative brings together the good, the bad, and the cowardly in a place of healing: a Freetown hospital to which a British psychologist has come to work as a specialist in stress disorder. The story that unfolds is a moving portrayal of love and hope and the undying human spirit.

Jude Dibia, author of Blackbird: There are a few novels of note written by black authors that I read this year, and one that comes readily to mind is Fine Boys by Eghosa Imasuen. This was a story that was as beautiful as it was tragic and revelatory. It told the tale of two childhood friends living in a country marred by military coups. Striking in this novel is the portrayal of friendship and family as well as the exploration of cult-driven violence in Nigerian universities.

Simidele Dosekun, author of Beem Explores Africa: My favorite read this year was The Memory of Love (Bloomsbury, 2011) by Aminatta Forna. Set in Freetown, Sierra Leone before and after the war, it tells of intersecting lives and loves thwarted by politics. I read it suspended in an ether of foreboding about where one man’s obsession with another’s wife would lead, and could not have anticipated its turns. As for children’s books, I have lost count of the copies of Lola Shoneyin’s Mayowa and the Masquerades that I have given out as presents. It is a colorful and chirpy book that kids will love.

Dayo Forster, author of Reading the Ceiling: It is worth slogging past the first few pages of Binyavanga Wainaina’s memoir, One Day I Will Write About This Place, to get to a brilliantly captured early memory -- a skirmish outside his mother’s salon about the precise placement of rubbish bins. Other poignant moments abound -- as a student in South Africa, a resident of a poor urban area in Nairobi, adventures as an agricultural extension worker, a family gathering in Uganda. With the personal come some deep revelations about contemporary Kenya. Read it.

Petina Gappah, author of An Elegy for Easterly: I did not read many new books this year as I spent most of my time reading dead authors. Of the new novels that I did read, I most enjoyed The Marriage Plot by Jeffrey Eugenides, who writes once every decade, it seems, and is always worth the wait. I also loved Open City by Teju Cole, which I reviewed for the Observer. I was completely overwhelmed by George Eliot’s Middlemarch and W. Somerset Maugham’s Of Human Bondage, both of which I read for the first time this year, and have since reread several times. I hope, one day, or maybe one decade, to write a novel like Middlemarch.

Maggie Gee, author of My Animal Life: I re-read Bernardine Evaristo’s fascinating fictionalized family history, the new, expanded Lara, tracing the roots of this mixed race British writer back through the centuries to Nigeria, Brazil, Germany, Ireland -- comedy and tragedy, all in light-footed, dancing verse. In Selma Dabbagh’s new Out of It, the lives of young Palestinians in Gaza are brought vividly to life -- gripping, angry, funny, political. Somewhere Else, Even Here by A.J. Ashworth is a stunningly original first collection of short stories.

Ivor Hartmann, co-editor of the African Roar anthologies: Blackbird by Jude Dibia is a deeply revealing contemporary look at the human condition, yet compassionate throughout, well paced, and not without its lighter moments for balance. The Collected Stories of Arthur C. Clarke, spans 61 years of his short stories and shows a clear progression of one of the kings of Sci-Fi. The Way to Paradise by Mario Vargas Llosa is a vast, powerful, and masterful work, which focused on Paul Gauguin (and his grandmother).

Ikhide R. Ikheloa, book reviewer and blogger: I read several books whenever I was not travelling the world inside my iPad, by far the best book the world has never written. Of traditional books, I enjoyed the following: Blackbird by Jude Dibia, Open City (Random House, 2011) by Teju Cole, One Day I Will Write About This Place (Graywolf, 2011) by Binyavanga Wainaina, and Tiny Sunbirds, Far Away by Christie Watson. These four books bring readers face-to-face with the sum of our varied experiences -- and locate everyone in a shared humanity, and with dignity. They may not be perfect books, but you are never quite the same after the reading experience.

Eghosa Imasuen, author of Fine Boys: American Gods (William Morrow; 10 Anv ed., 2011) by Neil Gaiman is a novel of hope, of home, and of exile. It superbly interweaves Gaiman’s version of Americana with the plight of “old world” gods, many of them recognizable only by the subtlest of hints. We watch as these old gods do battle with humanity’s new gods: television, the internet, Medicare, and a superbly rendered personification of the sitcom. Read this book, and see the awkward boundaries between literary and genre fiction blur and disappear.

Tade Ipadeola, poet and president of PEN Nigeria: An Infinite Longing for Love by Lisa Combrinck. The voluptuous verse in this stunning book of poetry is a triumph of talent and a validation of the poetic tradition pioneered by Dennis Brutus. I strongly recommend this book for sheer brilliance, and for how it succors the human condition. Desert by J.M.G Le Clézio emerges essentially intact from translation into English, and it weaves a fascinating take of the oldest inhabitants of the Sahara. It’s Our Turn to Eat: The Story of a Kenyan Whistleblower by Michela Wrong tackles endemic corruption in Africa and the global response -- a powerful book.

David Kaiza, essayist: The Guardian voted The Age of Extremes by Eric Hobsbawm as one of the top 100 books of the past century. I don’t care much for these listings, but there is a lot of truth to that choice. Hobsbawm is a Marxist historian, and his insight into the 200 years that re-shaped man’s world (and, as he says, changed a 10,000-year rhythm of human society) is transformational. In 2011, I read 10 of his books, including the priceless Bandits which put Hollywood’s Western genre in perspective and, among others, made me appreciate The Assassination of Jesse James as much as I understood Antonio Banderas’ Puss in Boots. There must be something to a historian who makes you take animation seriously.

Nii Ayikwei Parkes, author of Tail of the Blue Bird: This year I finally managed to read and fall in love with The Last Brother by Nathacha Appanah, which had been sitting on my shelf since last year. It draws on the little-known true incident of a ship of European Jews forced into temporary exile in Mauritius close to the end of the Second World War and weaves around it a simple, compelling story of friendship between two boys -- one a Jewish boy in captivity, the other an Indian-origin Mauritian who has already known incredible trauma at a young age. The friendship ends in tragedy, but in the short space of its flowering and the lives that follow, Nathacha Appanah manages to explore the nature of human connection, love, and endurance, and the place of serendipity in ordering lives. A great read. My plea to my fellow Africans would be to pay more attention to writing from the more peripheral countries like Mauritius and the Lusophone countries; there is some great work coming out of the continent from all fronts. Given my fascination with language, especially sparsely-documented African languages and the stories they can tell us, I have been enjoying Guy Deutscher’s Through the Language Glass, which is a fascinating re-examination of the assumptions language scholars have made for years. Drawing on examples from Australia, Europe, Africa, Asia, and America, he argues that contrary to popular lore, languages don’t limit what we can imagine but they do affect the details we focus on -- for example, a language like French compels you to state the gender if you say you are meeting a friend, whereas English does not. Brilliantly written and accessible, I’d recommend it for anyone who has ever considered thinking of languages in terms of superior and inferior.

Adewale Maja-Pearce, author of A Peculiar Tragedy: Eichmann in Jerusalem by Hannah Arendt. Her argument was the presumed complicity of Jews themselves in Hitler’s holocaust, which necessarily created considerable controversy. Eichmann was a loyal Nazi who ensured the deaths of many before fleeing to Argentina. He was kidnapped by Israel and put on trial, but the figure he cut seemed to the author to reveal the ultimate bureaucrat pleased with his unswerving loyalty to duly constituted authority, hence the famous “banality of evil” phrase she coined. Arendt also notes that throughout Nazi-occupied Europe, only Denmark, Italy, and Bulgaria resisted rounding up their Jewish populations as unacceptable.

Maaza Mengiste, author of Beneath the Lion’s Gaze: I couldn’t put down Season of Migration to the North by Tayeb Salih and wondered what took me so long discover it. The story follows a young man who returns to his village near the Nile in Sudan after years studying aboard. There is startling honesty in these pages, as well as prose so breathtakingly lyrical it makes ugly truths palatable. With a new introduction by writer Laila Lalami, even if you’ve read it once, it could be time to pick it up again. What more can I add to the rave reviews that have come out about the memoir One Day I Will Write About this Place by Binyavanga Wainaina? I found myself holding my breath in some parts, laughing in others, feeling my heart break for him as he tries to find his way in a confusing world. Wainaina’s gaze on his continent, his country, his family and friends, on himself is unflinching without being cruel. The writing is exhilarating. It explodes off the page with an energy that kept me firmly rooted in the world of his imagination and the memories of his childhood. By the end, I felt as if a new language had opened up, a way of understanding literature and identity and what it means to be from this magnificent continent of Africa in the midst of globalization. It’s been hard to consider the Arab Spring without thinking about the African immigrants who were trapped in the violence. The Italian graphic novel Etenesh by Paolo Castaldi tells of one Ethiopian woman’s harrowing journey from Addis Ababa to Libya and then on to Europe. At the mercy of human traffickers, numbed by hunger and thirst in the Sahara desert, Etenesh watches many die along the way, victims of cruelties she’ll never forget. Thousands continue to make the same trek today -- struggling to survive against all odds. Her story is a call to remember those still lost in what has become another middle passage.

Nnedi Okorafor, author of Who Fears Death: Habibi by Craig Thompson is easily the best book I’ve read this year. It is a graphic novel that combines several art forms at once. There is lush Arabic calligraphy that meshes with unflinching narrative that bleeds into religious folklore that remembers vivid imagery. Every page is detailed art. The main characters are an African man and an Arab woman, and both are slaves. Also, the story is simultaneously modern and ancient and this is reflected in the setting. There are harems, eunuchs, skyscrapers, pollution. I can gush on and on about this book and still not do it justice.

Chibundu Onuzo, author of The Spider King’s Daughter: The Help by Kathryn Stockett struck all the right chords. The plot was compelling, the characters were sympathetic, and the theme of race relations is ever topical. If you’re looking for a gritty, strictly historical portrait of life as a black maid in segregated Mississippi, perhaps this book is not for you. But if you want to be entertained, then grab The Help.

Shailja Patel, author of Migritude: In this tenth anniversary year of 9/11, the hauntingly lovely Minaret by Leila Aboulela is the “9/11 novel” I recommend, for its compelling story that confounds all expectations. Hilary Mantel’s epic Booker Prize winner, Wolf Hall, had me riveted for a full four days. It shows how a novel can be a breathtaking ride through history, politics, and economics. Everybody Loves A Good Drought: Stories From India’s Poorest Districts by P. Sainath should be compulsory reading for everyone involved in the missionary enterprise of “development.”

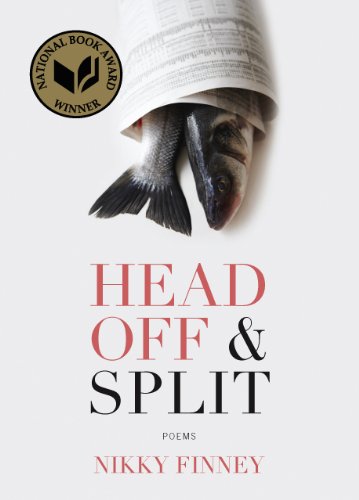

Laura Pegram, founding editor of Kweli Journal: Thelonious Monk: The Life and Times of an American Original by Robin D.G. Kelley is “the most comprehensive treatment of Monk’s life to date.” The reader is finally allowed to know the man and his music, as well as the folks who shaped him. On Black Sisters Street by Chika Unigwe. In this novel, the reader comes to know sisters with “half-peeled scabs over old wounds” who use sex to survive in Antwerp. Winner of this year’s National Book Award for poetry, Head Off & Split by Nikky Finney is a stunning work of graceful remembrance.

Henrietta Rose-Innes, author of Nineveh: Edited by Helon Habila, The Granta Book of the African Short Story is a satisfyingly chunky volume of 29 stories by some of the continent’s most dynamic writers, both new and established. The always excellent Ivan Vladislavic’s recent collection, The Loss Library, about unfinished/unfinishable writing, offers a series of brilliant meditations on the act of writing -- or failing to write. And recently I’ve been rereading Return of the moon: Versions from the /Xam by the poet Stephen Watson, who tragically passed away earlier this year. I love these haunting interpretations of stories and testimonies from the vanished world of /Xam-speaking hunter-gatherers.

Madeleine Thien, author of Dogs at the Perimeter: Some years ago, the Chinese essayist, Liao Yiwu published The Corpse Walker, a series of interviews with men and women whose aspirations, downfalls, and reversals of fortune would not be out of place in the fictions of Dickens, Dostoevsky or Hrabal. The Corpse Walker is a masterpiece, reconstructing and distilling the stories of individuals -- an Abbott, a Composer, a Tiananmen Father, among so many others -- whose lives, together, create a textured and unforgettable history of contemporary China. Liao’s empathy and humour, and his great, listening soul, have created literature of the highest calibre. My other loved books from this year are the Dutch novelist Cees Nooteboom’s story collection The Foxes Come at Night, a visionary and beautiful work, and Barbara Demick’s Nothing to Envy: Ordinary Lives in North Korea.

Chika Unigwe, author of On Black Sisters Street: Contemporary Chinese Women Writers II has got to be one of my favorite books of the year. I recently picked it up in a delightful bookshop in London. When I was growing up in Enugu, I was lucky to live very close to three bookshops, and I would often go in to browse, and sometimes buy books. It was in one of those bookstores that I discovered a dusty copy of Chinese Literature -- and I flipped through and became thoroughly enchanted. I bought the copy and had my father take out a subscription for me. For the next few years the journal was delivered to our home, and I almost always enjoyed all the stories but my favorite was a jewel by Bi Shumin titled “Broken Transformers.” I never forgot that story and was thrilled to discover it (along with five other fantastic short stories) in this anthology.

Uzor Maxim Uzoatu, author of God of Poetry: Search Sweet Country by B. Kojo Laing is a great novel that curiously remains unsung. Originally published in 1986, and reissued in 2011 with an exultant foreword by Kenyan writer Binyavanga Wainaina, Search Sweet Country is a sweeping take on Ghana in the years of dire straits. As eloquent as anything you will ever read anywhere, the novel is filled with neologisms and peopled with unforgettable characters. B. Kojo Laing is sui generis.

Zukiswa Wanner, author of Men of the South: On a continent where dictators are dying as new ones are born, Ahmadou Kourouma’s Waiting for the Wild Beast to Vote remains for me one of the best political satires Africa has yet produced. I Do Not Come to You By Chance by Adaobi Tricia Nwaubani is a rib-cracking book highlighting a situation that everyone with an email account has become accustomed to, 419 scam letters. The beauty and the hilarity of this book stems from the fact that it is written -- and written well -- from the perspective of a scammer.

Michela Wrong, author of It’s Our Turn to Eat: The Story of a Kenyan Whistleblower: Season of Rains: Africa in the World by Stephen Ellis. It’s rare for a book to make you think about the same old subjects in fresh ways. The tell-tale sign, with me, is the yellow highlighting I feel obliged to inflict upon its pages. My copy of Ellis’ book is a mass of yellow. It’s a short and accessibly-written tome, but packs a weighty punch. Ellis tackles our preconceptions about the continent, chewing up and spitting out matters of state and questions of aid, development, culture, spirituality, Africa's past history and likely future. The cover photo and title both failed to impress me but who cares, given the content?

“Horrible things happen everywhere”: The Millions Interview with Craig Thompson

Habibi, Craig Thompson’s first graphic novel in eight years, is a sorrowful epic pipe dream of Muslim culture filtered through a Westernized lens. It tells the story of Dodola and Zam, two child slaves living in a vicious universe in which rape and murder are assumed facts of life. The details can be jarring. The soldiers in his fictional Arabian Nights-inspired kingdom of Wanatolia have daggers but no guns, while street vendors sell slaves in chains next to DVD stands. Still, one need change only one or two small facts of our history and his book could serve as a cousin to the non-fiction comics journalism of Joe Sacco.

Thompson spent a day on most pages of his book. Certain pages, the ones that include intricate Middle Eastern designs, took three days. The cartoonish surrealism of Thompson’s first book Good-bye, Chunky Rice and the simplified, stripped-down drawings in his account of first love in Blankets offered some solace against depictions of abuse and sexual frustration. But the exotic, overbearing detail of Habibi can disturb. The beauty of the book both attracts and alienates.

I met Thompson at the home of mutual friends, a Spanish couple, a writer and painter, in Iowa City on the morning of September 25. The hotels in town were overbooked thanks to a Saturday football game, so he had stayed there the night before. He met me at the door, wearing yesterday’s shirt, looking well-rested. We sat in a huge white room. Sunlight came in from long vertical windows hitting several paintings, including a few of recognizable spots in Iowa City. A cat came by occasionally to rub up against our legs. What follows is a pared-down version of our interview.

The Millions: Was there any moment as you were beginning this book when you sought permission to write it? You are a white person from a very Christian family in Wisconsin. Was there any voice in the back of your head saying, “You don’t get to write about black people or Arab people in the Muslim world”?

Craig Thompson: I didn’t worry about that specifically, partly because the two characters -- Dodola and Zam, an Arab girl and a black boy -- delivered themselves fully realized from my subconscious. So they already were characters that existed outside of me and they dictated a lot of the things they did. I trusted the Turkish writer Elif Shafak -- she wrote The Bastard of Istanbul -- who describes fiction as a way to live other lives and in other worlds. You don’t need to have those experiences directly. It’s almost a shamanistic journey where by tapping your own imagination you access these other roles. And I trusted that.

With all my work, I struggle with giving myself permission to do it. And that comes from coming from a very religious household and a very anti-art household.

I come from very lower-working-class roots, so it’s not like my parents wanted me to have a more high-powered career, like being a doctor. They actually wanted me to have a more modest career, like being an electrician, something that’s very practical. [They wanted me to do] something that serves society rather than [something that] serves oneself, which is their perception of art. Every day I struggle with allowing myself to be an artist. And I have to try to trust the instinct that hopefully art also helps other people and not just oneself.

TM: Do you graft a Christian ethos onto your art then?

CT: Well, for me the Christian ethos is not to judge other people. No human can judge another. I think I am true to that in my art. When you’re a writer, you’re not judging your characters. You can live a lot of different roles on paper without judgment.