As we’ve done for several years now, we thought it might be fun to compare the U.S. and U.K. book cover designs of this year’s Morning News Tournament of Books contenders. Book cover art is an interesting element of the literary world — sometimes fixated upon, sometimes ignored — but, as readers, we are undoubtedly swayed by the little billboard that is the cover of every book we read. And, while many of us no longer do most of our reading on physical books with physical covers, those same cover images now beckon us from their grids in the various online bookstores. From my days as a bookseller, when import titles would sometimes find their way into our store, I’ve always found it especially interesting that the U.K. and U.S. covers often differ from one another. This would seem to suggest that certain layouts and imagery will better appeal to readers on one side of the Atlantic rather than the other. These differences are especially striking when we look at the covers side by side. The American covers are on the left, and the UK are on the right. Your equally inexpert analysis is encouraged in the comments.

Judging Books by Their Covers 2013: U.S. Vs. U.K.

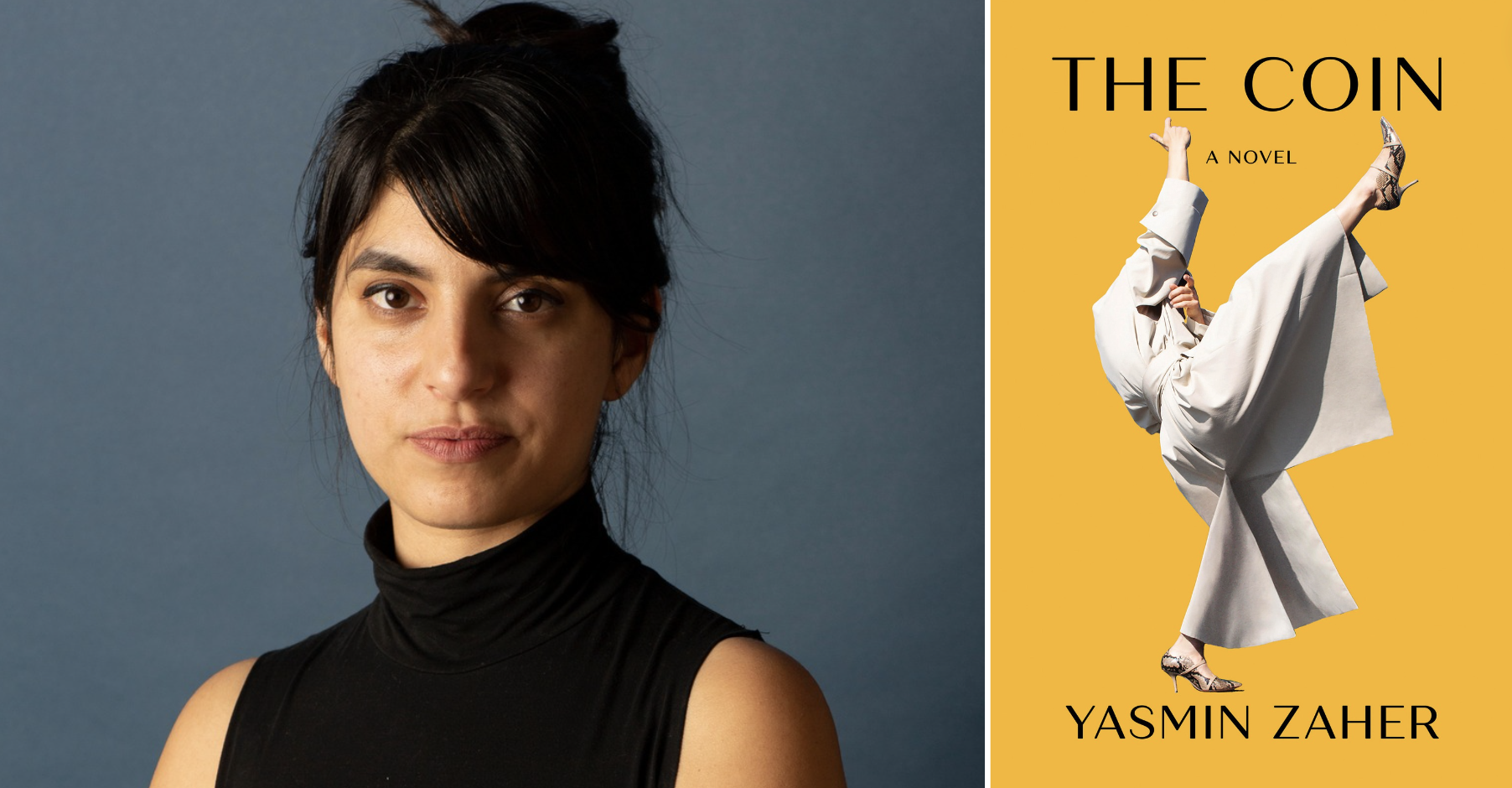

How Yasmin Zaher Wrote the Year’s Best New York City Novel

"This is going to sound absurd, but in a novel, you can say the truth, and in journalism, you cannot."

●

●

●

Things Got Weird: On the Early ‘90s Crack-Up

Ganz vividly renders the early 1990s’ shouty yet blankly confused alienations along with the endlessly gassy and vituperative “whither America?” debates.

●

●

●

●

●

●

The Beguiling Crónicas of Hebe Uhart

'A Question of Belonging' is marked by an unerring belief that a good story can be found almost anywhere.

●

●

●