On three occasions I have performed my civic duty and worked as a poll inspector on election day, an experience for which I reaped the pride of performing one’s civic duty and 150 U.S. dollars. On the occasion of the 2008 primary election, I assisted a gentleman who, like many San Francisco citizens believing themselves to have registered as independent voters, had in fact checked the box for the far-far-right American Independent Party. When these voters showed up on election day, they were presented with a bewildering list of candidates from their party of record. This man told me, “I am trying to vote for the President of the United States of America,” gesticulating to his ballot as if to say, “not this mess.”

It’s a little bit how I feel when I look at The New York Times bestseller list or trawl the front table of a reputable book shop, fondling the covers, reading the backs, feeling frustrated and indecisive and confused: which among these is the yearned-for genius? It’s a wholly unjust parallel, because my wholly unreasonable sense that there aren’t enough geniuses who write novels to amuse me is in no way comparable to an American citizen’s actual voter disenfranchisement resulting from paperwork ambiguities.* But to me, novels are the highest office of the land, and I have very specific and very high expectations for them.

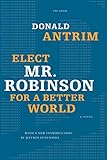

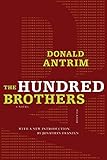

Donald Antrim came to me in three economical little volumes. I did not know about Donald Antrim, and I believe this puts me squarely in the demographic Picador hoped to reach with its re-release of three novels, each featuring an introduction by a big name (Jeffrey Eugenides, Jonathan Franzen, George Saunders). I am grateful, because now I do know about him, his books anyway, and I believe him to be one of the great American writers alive today. Here is my yearned-for genius.

Elect Mr. Robinson for a Better World — the first of a trilogy that also includes The Hundred Brothers and The Verificationist — hit me like the proverbial ton of bricks. In this grim and comic novel, the titular Robinson, an educator and pillar of his Florida community, narrates his descent into a madness even nastier than the one gripping his compatriots. This is America of the heavily-armed future (more heavily-armed, we should say), maybe the fevered dream of the aforementioned American Independent Party (from their website: “We also insist that those who violate our immigration laws…be punished for their crime in a way that will deter them from future offenses.”) The residents of Antrim’s novel build death traps in front of gracious homes — including Robinson’s wife, Meredith, who reclines “in an aluminum chaise, idly carving and shaping bamboo stalks macheted, the previous day, from thickets lining a nearby canal. ‘I love our old house,'” she says, sounding for the world like my very own mother planting an azalea.

Elect Mr. Robinson for a Better World — the first of a trilogy that also includes The Hundred Brothers and The Verificationist — hit me like the proverbial ton of bricks. In this grim and comic novel, the titular Robinson, an educator and pillar of his Florida community, narrates his descent into a madness even nastier than the one gripping his compatriots. This is America of the heavily-armed future (more heavily-armed, we should say), maybe the fevered dream of the aforementioned American Independent Party (from their website: “We also insist that those who violate our immigration laws…be punished for their crime in a way that will deter them from future offenses.”) The residents of Antrim’s novel build death traps in front of gracious homes — including Robinson’s wife, Meredith, who reclines “in an aluminum chaise, idly carving and shaping bamboo stalks macheted, the previous day, from thickets lining a nearby canal. ‘I love our old house,'” she says, sounding for the world like my very own mother planting an azalea.

Mr. Robinson is trying to get a new school going in an increasing fractious and militarized community, where taxpayers have defunded public education and feuding neighbors plant mines in public parks. Mr. Robinson has his eye on a mayoral run; he gives pedantic lectures on medieval torture to rapt audiences. He feels left out as his wife, the center of a new spiritual movement, swims away from him in “icthyomorphic trances.”

In his introduction, Jeffrey Eugenides called Elect Mr. Robinson “a book without antecedents. To compare it to other books is to invite frustration: the templates don’t match up.” In one sense this is true, because the book, all of the books, enact a collision of the real and the surreal that is novel, and extremely jarring (also thrilling). But I hark back to English class (the one place where Freud’s taxonomies are still ascendant) and I think that part of the success of this novel lies in its heavy invocation of the unheimlich , and not only because it describes a balmy burg where Rotarians draw and quarter civic leaders with their Japanese cars. For me it’s the uncanny echo of the great feckless men of American literature — the heroes of Bellow and Irving, their comparatively harmless peccadilloes — that titillates.

When Mr. Robinson appears in the public library for children’s story hour, toting a desecrated book and grisly after a night spent burying a severed foot in a public park, I chortled at the memory of Bogus Trumper returning home befeathered and gore-smeared in The Water-Method Man, holding an expired duck (Mr. Robinson trades his library book for a stuffed buffalo). It’s not that this book has no antecedents — like the other books in the trilogy it’s basically about a guy who’s going through some stuff — but the familiar rake has been transplanted to a murderous and depraved universe.

When Mr. Robinson appears in the public library for children’s story hour, toting a desecrated book and grisly after a night spent burying a severed foot in a public park, I chortled at the memory of Bogus Trumper returning home befeathered and gore-smeared in The Water-Method Man, holding an expired duck (Mr. Robinson trades his library book for a stuffed buffalo). It’s not that this book has no antecedents — like the other books in the trilogy it’s basically about a guy who’s going through some stuff — but the familiar rake has been transplanted to a murderous and depraved universe.

These novels should be read together — Antrim’s prowess, the profound and various weirdness of his three narrators is best appreciated in concert. The Hundred Brothers is literally a novel about a hundred brothers jostling around in a rotting mansion — among them “Albert, who is blind; and Siegfried, the sculptor in burning steel; and clinically depressed Anton, schizophrenic Irv, recovering addict Clayton; and Maxwell, the tropical botanist” — a bunch of guys being guys until it’s time for a symbolic ritual sacrifice in the labyrinthine library. As Jonathan Franzen (the songbird conservationist) correctly observes, “The Hundred Brothers is possibly the strangest novel ever published by an American.”

These novels should be read together — Antrim’s prowess, the profound and various weirdness of his three narrators is best appreciated in concert. The Hundred Brothers is literally a novel about a hundred brothers jostling around in a rotting mansion — among them “Albert, who is blind; and Siegfried, the sculptor in burning steel; and clinically depressed Anton, schizophrenic Irv, recovering addict Clayton; and Maxwell, the tropical botanist” — a bunch of guys being guys until it’s time for a symbolic ritual sacrifice in the labyrinthine library. As Jonathan Franzen (the songbird conservationist) correctly observes, “The Hundred Brothers is possibly the strangest novel ever published by an American.”

As in the other novels, real, melancholy insights are juxtaposed with zingers in a way that demonstrates the range and flexibility of Antrim’s intellect — and that of his narrator:

Conflict is always so difficult to recount…The technical aspects of describing true conflict are daunting. First, you have to establish your antagonists. It is important to avoid cozy oversimplifications, and to bear down instead on all the obscure and intractable problems of identity and desire that make our lives and our needs so various and dissimilar. The problems in describing a person are essentially problems of knowing a person. One of the sad features of most close relationships is the decay of intimacy as a function of time, turmoil, and all the little misunderstandings that inevitably occur between people, leading them, year in and year out, toward the same tired conclusions: conversation falters; friendships fail.

That said, allow me to concede that my brother Hiram is an incredible asshole. He’s just a complete jerk. He finds your worst insecurities and then tortures you until you’ll do practically anything to escape his voice’s dry wheezing and the spectacle of bony fists clutching that walker.

The female only child cringes at the rampant punching, the crumbling ceilings, the ruined books, the confirmation writ large of the singleton’s suspicion that sibling stuff is weird. The book, the house, is overstuffed with crazed men and marvelous set pieces.

The trilogy ends with The Verificationist, which, like a joke at a professional conference, opens with a group of clinical psychologists having breakfast in an all-night pancake joint. The narrator’s predilection for starting food fights and instigating mayhem leads Bernhardt, the most grotesque and overbearing from among his colleagues, to hold him around his midsection almost for the duration of the novel. Pinned by Bernhardt, our narrator ascends for a night flight — both a respectable narrative (and religious) trope and the stuff of psychotic breaks.

The trilogy ends with The Verificationist, which, like a joke at a professional conference, opens with a group of clinical psychologists having breakfast in an all-night pancake joint. The narrator’s predilection for starting food fights and instigating mayhem leads Bernhardt, the most grotesque and overbearing from among his colleagues, to hold him around his midsection almost for the duration of the novel. Pinned by Bernhardt, our narrator ascends for a night flight — both a respectable narrative (and religious) trope and the stuff of psychotic breaks.

Taking place mostly on a ceiling, The Verificationist was probably my least favorite of the three in terms of plot (a ludicrous metric for these novels, I suppose). It might, however, contain the greatest number of killer lines and passages. Holding the narrator aloft, “Bernhardt the horrible father whispered into my ear, ‘You’re nothing but trouble, Tom. That’s why we love you. I know it may surprise you to hear that we love you, but it’s true. I’ll say it again. We’re your coworkers, and we love you.'” Or: “‘I can’t believe it. You bayoneted Dad! And I trusted you,’ declares the girl — brilliantly commandeering, in the way offended people so frequently will, events that occurred years in the past, using them as retrospective evidence pertaining to present circumstances.” Like the other novels, The Verificationist is very funny; like the others, it ends dark and sad.

The oldest of the trilogy, Elect Mr. Robinson is already almost two decades old, sufficiently old to qualify it, I guess, for re-release with a new introduction. But I suspect it’s not so much a function of age that has these books reappearing now. Rather, someone out there knew they hadn’t had their fair shake. They knew there were people who needed these novels — frustrated people and weird people and people who prefer a very correct, very unusual deployment of the English language: formal but personal, arch, hilarious, possessed of a slightly antiquarian flavor. Even very great writers don’t often write like this.

So when you’ve surfeited yourself on hunger games and vampires and zombies and lukewarm bondage and everything else that dulled our synapses this year — when you need a new genius — don’t despair, choose Donald Antrim.

__

*Too late for this man but fortunately for other voters, the registration language for independent voters was changed from “decline-to-state” to “no party preference.”