Difficult relationships between fathers and sons have been fodder for writers for millennia. Sometimes these relationships are simply power struggles, as in so many Greek myths, such as the conflicts first between Uranus and his son Cronus and later Cronus and his son Zeus. Or their conflicts are representative of social strife, as in Ivan Turgenev’s Fathers and Sons. And other times, like in many of Franz Kafka’s most famous works, they’re about, well, Kafka. But no one writing today has explored the mercurial nature of the father-son relationship with more humor and fresh insight than Adam Ehrlich Sachs. Now, with the publication of his third book, Gretel and the Great War, Sachs is broadening his canvas to put this core dynamic in the context of social upheaval, obsession, and, above all, legacy.

Difficult relationships between fathers and sons have been fodder for writers for millennia. Sometimes these relationships are simply power struggles, as in so many Greek myths, such as the conflicts first between Uranus and his son Cronus and later Cronus and his son Zeus. Or their conflicts are representative of social strife, as in Ivan Turgenev’s Fathers and Sons. And other times, like in many of Franz Kafka’s most famous works, they’re about, well, Kafka. But no one writing today has explored the mercurial nature of the father-son relationship with more humor and fresh insight than Adam Ehrlich Sachs. Now, with the publication of his third book, Gretel and the Great War, Sachs is broadening his canvas to put this core dynamic in the context of social upheaval, obsession, and, above all, legacy.

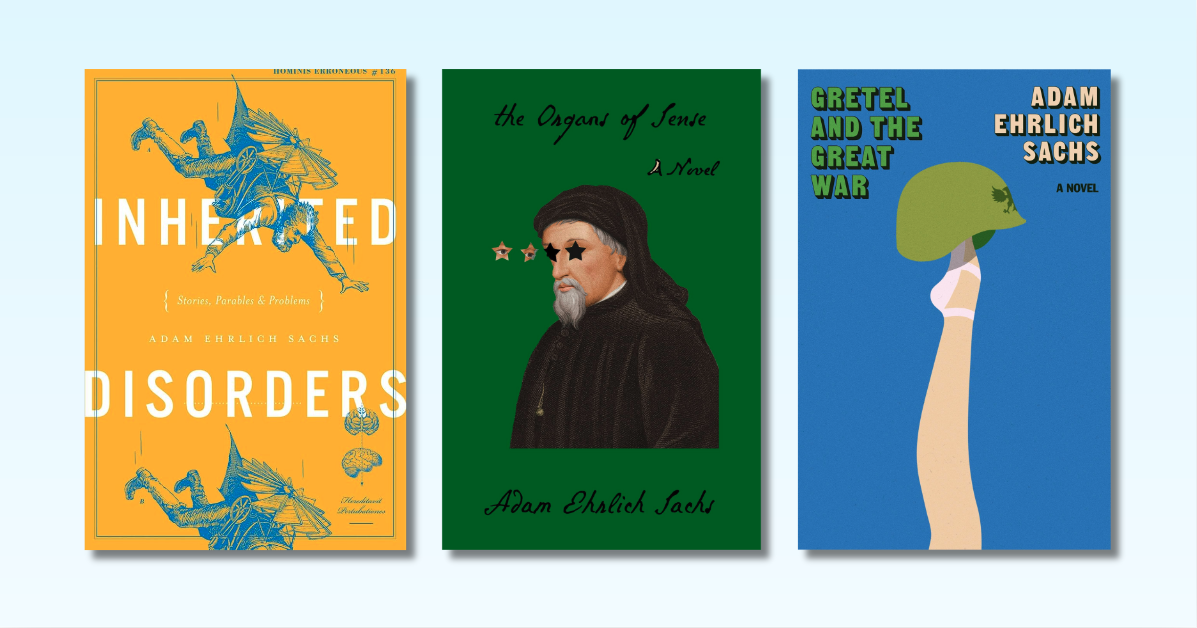

For those unfamiliar with Sachs, reading his three books in chronological order offers an opportunity to see a writer honing his voice and developing a unique style. But perhaps the best way to appreciate Sachs, particularly his growth as a storyteller, is to examine the three literary father figures who have each had an increasingly significant influence on his works, beginning with Kafka.

“You asked me recently,” begins Kafka’s unsent letter to his father, “why I maintain that I am afraid of you. As usual, I was unable to think of any answer to your question, partly for the very reason that I am afraid of you, and partly because an explanation of the grounds for this fear would mean going into far more detail than I could even approximately keep in mind while talking.” Based on these two sentences alone, with their combination of intellectual paralysis, concern with thorough explanations, and verbosity, Kafka  could have been a character straight out of Sachs’s first work, Inherited Disorders: Stories, Parables, and Problems. This collection is full of characters wrestling with the peculiar, often absurd, burdens inherent in being sons to peculiar, often absurd, fathers. One of my personal favorite stories involves an unlikely wager between a gymnast forced to carry the weight of generations of men on his back and a Russian mathematician compelled to work on a single problem that men in his family have passed down to their sons like a cursed heirloom. Yet whereas Kafka’s own complicated relationship with his father had an unmistakable impact on father-son relationships in his fiction, one senses that Sachs approaches this subject with a greater detachment: he finds it captivating without being held captive by it. The fathers and sons of these stories are kindly, vicious, mad, and everything in between. By the book’s end, one feels they have examined every possible permutation of father-son dynamics—and faced the impossibility of creating an identity that is not in some way a reaction to the influence of the previous generation, which inevitably foists its own obsessions onto its progeny.

could have been a character straight out of Sachs’s first work, Inherited Disorders: Stories, Parables, and Problems. This collection is full of characters wrestling with the peculiar, often absurd, burdens inherent in being sons to peculiar, often absurd, fathers. One of my personal favorite stories involves an unlikely wager between a gymnast forced to carry the weight of generations of men on his back and a Russian mathematician compelled to work on a single problem that men in his family have passed down to their sons like a cursed heirloom. Yet whereas Kafka’s own complicated relationship with his father had an unmistakable impact on father-son relationships in his fiction, one senses that Sachs approaches this subject with a greater detachment: he finds it captivating without being held captive by it. The fathers and sons of these stories are kindly, vicious, mad, and everything in between. By the book’s end, one feels they have examined every possible permutation of father-son dynamics—and faced the impossibility of creating an identity that is not in some way a reaction to the influence of the previous generation, which inevitably foists its own obsessions onto its progeny.

Sachs’s fascination with how obsession manifests and the myriad disasters that it brings about goes from thematic to formal with his second work, The Organs of Sense. On the one hand, the novel, about the bizarre life of an eyeless astronomer who confidently predicts a solar eclipse, could be seen as an extension of the kinds of stories in Inherited Disorders. But the drastically different style makes it a far more hypnotic reading experience. Sentences go on for pages, with the astronomer explaining what he was told by people who themselves were told things by others, all while the actual narrator narrates what the astronomer is explaining. This style is reminiscent of László Krasznahorkai and Gert Hoffmann, but the most illuminating comparison is Thomas Bernhard, a master of expressing frustration, particularly over unattainable dreams that curdle into bitter obsessions. The narrator of Bernhard’s 1985 novel Concrete, for instance, is supposed to be writing a book on music but instead tells the story of his failure to write anything. As his unrealized project increasingly defines his entire existence, his gaze turns inward, producing labyrinthine musings like:

Sachs’s fascination with how obsession manifests and the myriad disasters that it brings about goes from thematic to formal with his second work, The Organs of Sense. On the one hand, the novel, about the bizarre life of an eyeless astronomer who confidently predicts a solar eclipse, could be seen as an extension of the kinds of stories in Inherited Disorders. But the drastically different style makes it a far more hypnotic reading experience. Sentences go on for pages, with the astronomer explaining what he was told by people who themselves were told things by others, all while the actual narrator narrates what the astronomer is explaining. This style is reminiscent of László Krasznahorkai and Gert Hoffmann, but the most illuminating comparison is Thomas Bernhard, a master of expressing frustration, particularly over unattainable dreams that curdle into bitter obsessions. The narrator of Bernhard’s 1985 novel Concrete, for instance, is supposed to be writing a book on music but instead tells the story of his failure to write anything. As his unrealized project increasingly defines his entire existence, his gaze turns inward, producing labyrinthine musings like:

I must have made a pitiful, indeed pitiable impression on an observer, though there was none—unless I’m going to say that I am an observer of myself, which is stupid, since I am my own observer anyway: I’ve actually been observing myself for years, if not for decades; my life now consists only of self-observation and self-contemplation, which naturally leads to self-condemnation, self-rejection and self-mockery.

The characters of The Organs of Sense, like the astronomer who aims to produce a catalog of every single star in existence, might exhibit the same tendency to monomania. But just as Sachs bears Kafka’s influence while retaining his own voice, Sachs finds humor where Bernhard often only finds rage (or if there is humor, it’s in how much rage a single person can contain without exploding). Sachs also draws out comedy through linguistic precision. This can be seen in brief moments like when the astronomer demands a written guarantee of funding for his telescopes not within reason but “without” reason, or in a long and memorable episode involving glockenspiels. Much like Bernhard expresses frustration through meandering sentences, Sachs’s characters display the same kind of involuted thinking over pages as much over major plot points as minutiae that recall debates from Seinfeld.

The leap between Sachs’s second and third books is far greater than that between his first and second. Gretel and the Great War combines the best elements of Inherited Disorders and The Organs of Sense by functioning as a collection of episodes, like the former, while also subtly connecting plot elements so that they add up to a cohesive whole, like the latter. No longer content with just fathers and sons, Sachs explores how the anxieties and burdens in those relationships manifest in other familial or ersatz-familial bonds.

The leap between Sachs’s second and third books is far greater than that between his first and second. Gretel and the Great War combines the best elements of Inherited Disorders and The Organs of Sense by functioning as a collection of episodes, like the former, while also subtly connecting plot elements so that they add up to a cohesive whole, like the latter. No longer content with just fathers and sons, Sachs explores how the anxieties and burdens in those relationships manifest in other familial or ersatz-familial bonds.

Gretel and the Great War is presented as 26 bedtime stories sent by a man in an asylum to his daughter, who is taken in by a neurologist after she was found wandering the streets of Vienna. These stories, which often have a darker tone than those in his first collection, will appeal especially to readers who prefer the grim versions of Grimms’ Fairy Tales. On a first read, there are clues, whether in the form of locations or characters, that all these stories connect, allowing the reader to enjoy both the individual tales and the challenge of piecing them together. By the end, however, it is equally clear that these stories are connected not just by plot—rather, they collectively tell the story of a crumbling society. And it’s through this lens that the influence of Stefan Zweig becomes paramount.

Gretel and the Great War is presented as 26 bedtime stories sent by a man in an asylum to his daughter, who is taken in by a neurologist after she was found wandering the streets of Vienna. These stories, which often have a darker tone than those in his first collection, will appeal especially to readers who prefer the grim versions of Grimms’ Fairy Tales. On a first read, there are clues, whether in the form of locations or characters, that all these stories connect, allowing the reader to enjoy both the individual tales and the challenge of piecing them together. By the end, however, it is equally clear that these stories are connected not just by plot—rather, they collectively tell the story of a crumbling society. And it’s through this lens that the influence of Stefan Zweig becomes paramount.

Zweig’s influence was clear in Sachs’s earlier works, most notably his technique of having narrators tell stories told to them by eccentrics they meet on their travels. Zweig was also no stranger to having his plots center on obsession. But what distinguishes Gretel and the Great War is how Sachs begins to place his stories in the context of a particular historical moment. This occurs many times in Zweig’s novels, such as Journey into the Past, where a reunion between two lovers occurs just as a Nazi rally is beginning. The story has focused entirely on these two characters until now, making this intrusion of history all the more jarring. Like the imminent specter of World War II haunts Zweig’s later works, the approach of World War I—the titular Great War—haunts the Vienna of Sachs’s novel.

Zweig’s influence was clear in Sachs’s earlier works, most notably his technique of having narrators tell stories told to them by eccentrics they meet on their travels. Zweig was also no stranger to having his plots center on obsession. But what distinguishes Gretel and the Great War is how Sachs begins to place his stories in the context of a particular historical moment. This occurs many times in Zweig’s novels, such as Journey into the Past, where a reunion between two lovers occurs just as a Nazi rally is beginning. The story has focused entirely on these two characters until now, making this intrusion of history all the more jarring. Like the imminent specter of World War II haunts Zweig’s later works, the approach of World War I—the titular Great War—haunts the Vienna of Sachs’s novel.

In just three works, Sachs has already expanded his narrative territory considerably. Yet if there is one persistent theme it is a concern with legacy—the legacies we seek by chasing our dreams and those we leave to those unwillingly drawn into the orbit of our dreams. Perhaps Sachs will continue to explore this subject in future works, or maybe he will find a new vein to mine. Given his track record, whatever comes next will showcase the talents of a writer who has somehow managed to live up to, and with, the legacy of those who came before.