On a gravel road outside of Cheyenne, Wyoming, I stood before a Little Free Library painted the colors of the Pride flag. How had it arrived here in this deep-red state, so seemingly exposed and yet declaring itself with such self-assurance? This little library, which offered books and their stories for any passerby, must itself be a story.

I opened the library’s glass door and placed a fresh copy of my latest novel, What the Dead Can Say, on the bottom shelf. Then I returned to the car. For months my wife and I had been driving around the country, dropping off free copies of What the Dead Can Say in hundreds of Little Free Libraries. Now, we turned back on to the main road and headed down to Colorado, in search of more.

What the Dead Can Say is my eighth book. Over the course of my career, I’ve published books with Random House and Scribner, and fiction in the New Yorker. But for this most recent novel, I was no longer interested in chasing the prestige that such literary icons confer, no longer wished to jump through traditional publishing’s increasingly narrowing hoops. Instead, I decided to privately print a 1,000-copy limited edition run—then undertake a 10,000-mile journey through 28 states to give away every copy.

The origins of this journey date back to the summer of 1993. I was living in a rural village in West Africa with my wife, the cultural anthropologist Alma Gottlieb, on our third extended stay for her research among the Beng people of Côte d’Ivoire. The village was so isolated that when my father died back in the U.S., the news arrived too late to return home for his funeral. Devastated, we asked the village elders for permission to hold a traditional Beng funeral for my dad, and they agreed. Days after that public ceremony, Kokora Kouassi, a religious leader and friend, revealed that my father had appeared to him in a dream. He was now a member of Wurugbé, the Beng afterlife, where the dead live social lives invisibly among the living. “In Wurugbé,” Kouassi said, “people are the same. They all live together.” He assured me that my father’s spirit wasn’t far away, but hovering close by.

Kouassi’s empathetic words for a mourning son unlocked something, and in the following days 10 characters arose unbidden within me. Suspecting they would populate a future novel, I wrote their initial sketches in my notebook. They were all ghosts. And, though located in the U.S., their afterlife resembled the busy social afterlife of the Beng. Among them was a car mechanic whose afterlife is upended by his discovery of Books on Tape; the ghost of an unhappy 19th-century socialite who finally encounters peace when she inhabits an empty nautilus shell; and an entomologist who spends her afterlife in an ant nest, continuing her research. Then there was Jenny, the ghost of a three-year-old child whose story felt especially urgent to me; early in her afterlife, she develops the ability to absorb and share memories with the other ghosts she encounters in the novel, setting her on an unlikely adventure of balancing herself among these multiple selves.

I worked steadily on the book for 30 years, examining the cultural and historical complexities of America through the lens of ghosts of many eras and diverse backgrounds, all the while publishing four other books of fiction and nonfiction. Yet through all my ghost novel’s stops and starts, I wasn’t going to give up on Jenny, the character who spoke to me most deeply. Understanding the challenge of this ghost child’s afterlife helped me complete the novel. Jenny’s ability to gather and merge with the memories of the other ghosts she encounters certainly makes her unusual, but I realized that Jenny’s journey could be shared with any reader because we too, the living, are inhabited by others throughout our daily lives. Don’t we negotiate continually with our thoughts and memories of the people we know and have known? Whether they are near or far, their presences circle within us, and sometimes haunt us.

By the time I finished writing this very American version of the afterlife in the spring of 2022, What the Dead Can Say had been vetted by the careful readings of many fellow writers. Still, I felt reluctant to submit it to the ever more commercialized and corporatized process of traditional publishing, especially in this era of inflated, ghostwritten blurbs and ubiquitous, depressingly similar “blob” book covers. People who work in publishing love books, they champion their authors, but they’re embedded in a system that sways to the mantra of bottom line, bottom line, bottom line. The words of the late, great guitarist Ellen McIlwaine haunted me: “I’m tired of being on labels. It’s people with temporary jobs making permanent decisions about your career.” So I decided that who my book might reach would not be determined by the calculations of others—not for this novel, whose inspiration had been so deeply personal. I began to consider the path of independent filmmakers, who believe enough in their work to risk maxing out their credit cards.

Yet how to begin?

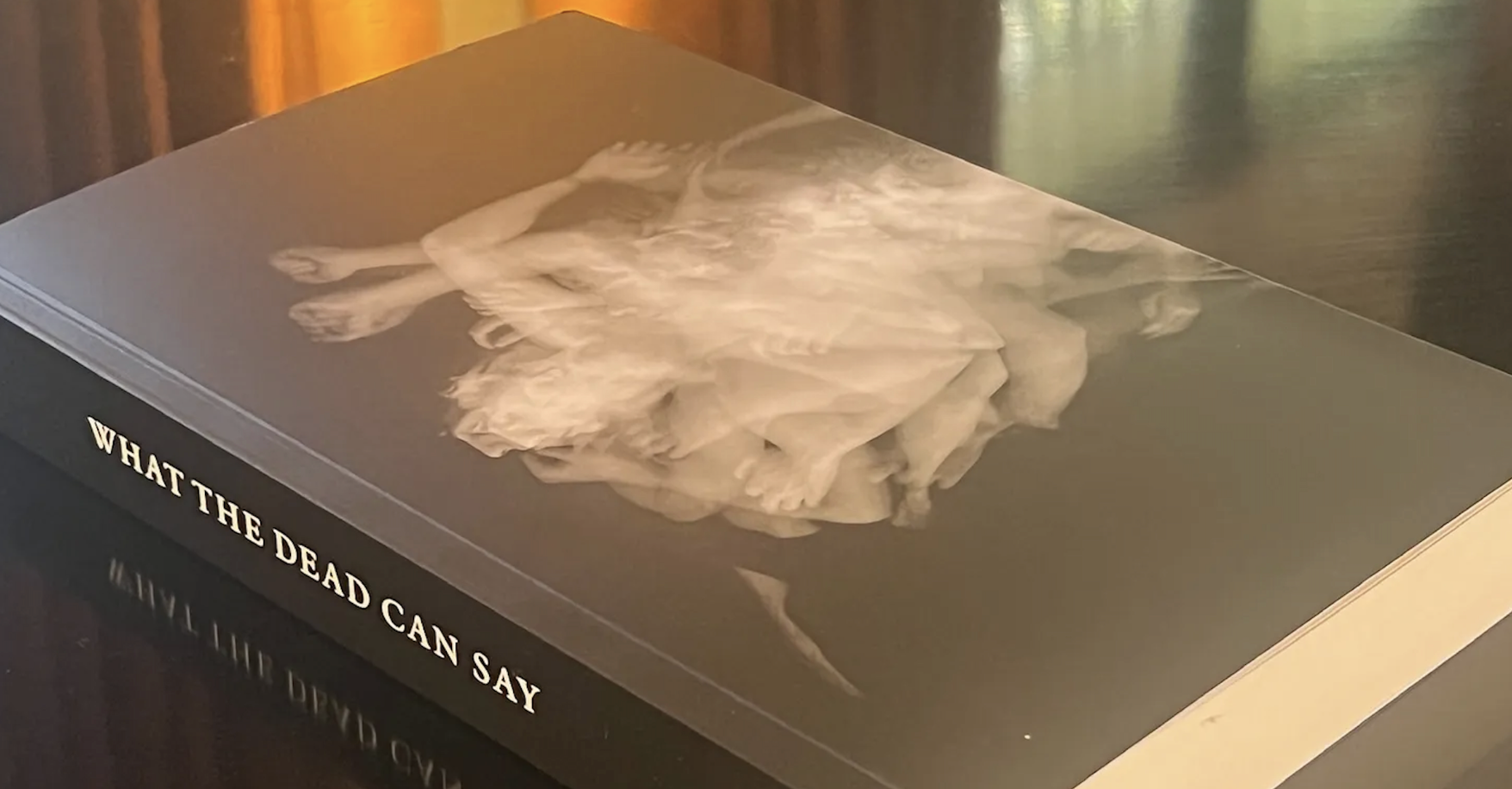

Over all those years, I’d come to imagine exactly how I wanted my book to look. In collaboration with like-minded designers, I created a book that followed its own rules. The black cover sports no title, only an evocative photographic image. There’s no author’s name to be found, only a pseudonym, Author Unseen, which appears only on the title page (printed just below an empty space where my signature, written in invisible ink, lurks). There are no plot giveaways on the front flap. No bloated blurbs crowd the back cover. The back flap contains no litany of honors, no bio at all.

All these choices were influenced by my childhood visits to the town library. Back in those days when librarians removed the jacket covers of newly acquired books, any book I picked from a shelf offered nothing to tease my interest other than the words themselves. I simply started reading. If I liked what I read, I took the book home. Why not, I now thought, present readers with a similar experience of mystery and discovery? But if my novel displayed none of the usual commercial trappings—not even a bar code, because I had no intention of selling it—how then would I reach readers?

Through their local Little Free Libraries.

To locate those readers, Alma and I scoured through the app of the Little Free Library organization, which features a map of the 150,000 little libraries registered across the U.S. Many of the little library listings included a photo and a paragraph about what type of books any given library favors. We marked those that held literary fiction or nonfiction, fantasy or science fiction, or those that simply offered an eclectic range of genres. Eventually, we chose several hundred that might welcome my novel. We’d flip the traditional model of book distribution on its head and transform it into a stealth act of performance art, in the hope that every copy would make it into the hands of a curious reader.

Throughout our long relationship, Alma and I had always been eager for adventure. Now, ready to embark on a new one, we hit the road, switching the roles of driver and navigator back and forth. We discovered that serious readers live everywhere. You can find a well-stocked Little Free Library on the street of a well-heeled suburb or in the center of an inner-city community garden, in a small rural town or on a busy urban bike path. Each little library is a form of public service, an expression of a neighborhood’s reading taste, a literary Rorschach blot, even a genre of sculpture: in Portland, Maine we came upon a little library shaped like a lighthouse; in Beacon, New York, one built out of dismantled piano parts; in Chicago, one resembling an Afghani bus. As the miles of our journey added up, we felt increasingly honored to enter into the invisible slipstream of fellow citizens who love and share books, all the while dropping off copies of a mystery in the shape of a book, as surprised readers in California, Oregon, and New Hampshire have attested online.

With our trek complete by the fall of 2023, I wasn’t yet ready to say goodbye to my ghostly Jenny—or to a project that questions how a book can be published and reach an audience. Now, a subscription-based serialization of What the Dead Can Say is available on the Ghost (yes, Ghost) online publishing platform. This digital version offers extra scenes, illustrations, and brief audio clips read by 21 writers (called the Jennyverse Chorus). The novel also expands into two extra final chapters that take place long after the events of the print version—chapters that extend Jenny’s story much farther than anything I could have imagined when the thought of her first came to me in a small village over 30 years ago.

That said, I don’t see my novel’s Little Free Library journey and its digital reincarnation as a specific template for other writers. At this point in my career, I’ve had the time and resources to realize my vision, advantages not available to everyone. If there’s anything that writers—especially younger writers—might glean from my experience, it is simply to imagine and embrace your own agency. In a publishing climate increasingly fueled by commercialism, don’t be afraid to find a space that most honors your work and, if you think you can, take some risks.