At the beginning of this year, we were living in Madrid and reliant, for our English-language reading, on what everyone referred to as the American Library but is formally called the Library of the International Institute of Madrid. My 7-year-old and I would visit almost every weekend; he’d read and play with the Spanish children visiting to practice their English, while I browsed the stacks. It’s a smallish membership-based library, largely stocked with books donated by members, and so I took what I could get, which led me for the first time in my life to pick up Graham Greene’s The End of the Affair, a novel that had never before interested me. It was a simpler book than I’d been led to believe, about a man’s affair with his friend’s wife. It was actually great. I devoured it the way I devour any story—written or otherwise—about someone’s affair with their friend’s wife. I should not, I told myself afterward, be so prejudiced against canonical white male writers.

At the beginning of this year, we were living in Madrid and reliant, for our English-language reading, on what everyone referred to as the American Library but is formally called the Library of the International Institute of Madrid. My 7-year-old and I would visit almost every weekend; he’d read and play with the Spanish children visiting to practice their English, while I browsed the stacks. It’s a smallish membership-based library, largely stocked with books donated by members, and so I took what I could get, which led me for the first time in my life to pick up Graham Greene’s The End of the Affair, a novel that had never before interested me. It was a simpler book than I’d been led to believe, about a man’s affair with his friend’s wife. It was actually great. I devoured it the way I devour any story—written or otherwise—about someone’s affair with their friend’s wife. I should not, I told myself afterward, be so prejudiced against canonical white male writers.

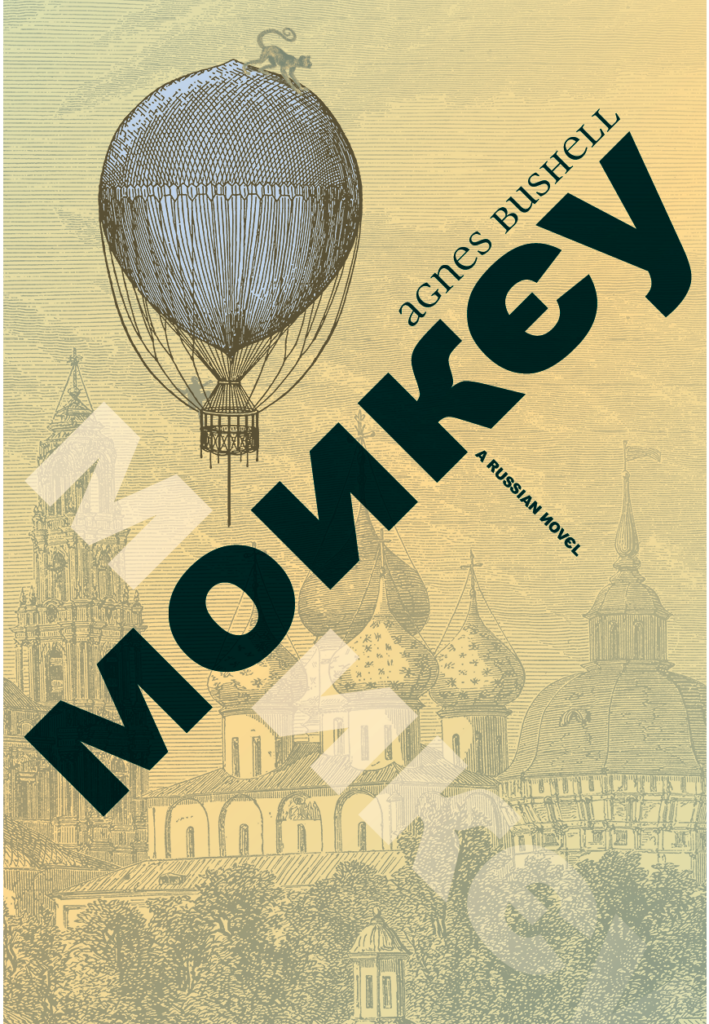

Before I had time to return to the library to make good on this plan, I was delivered a spreadsheet full of recently published novels, which I had agreed to read as a judge of the Community of Literary Magazines and Presses’s Firecracker Awards. We chose as a winner Zain Khalid’s unbelievably weird and brilliant Brother Alive. It was through judging these awards that I also encountered Nataliya Meshchaninova’s Stories of a Life (translated from Russian by Fiona Bell), about girlhood and womanhood in post-Soviet Russia, which was like reading a series of group-text missives from your funniest, smartest, and saddest friend; Irene Solà’s When I Sing, Mountains Dance (translated from Catalan by Mara Faye Lethem), which is convincingly narrated, in turns, from the perspective of a roe-deer, mountains, and the ghosts of the Spanish Civil War, among other characters; and Agnes Bushell’s Monkey, maybe my favorite of them all, a madcap 600-page opus, set in nineteenth-century Russia, about the missing author of a missing manuscript. My favorite parts were about the author’s suffering mother.

Before I had time to return to the library to make good on this plan, I was delivered a spreadsheet full of recently published novels, which I had agreed to read as a judge of the Community of Literary Magazines and Presses’s Firecracker Awards. We chose as a winner Zain Khalid’s unbelievably weird and brilliant Brother Alive. It was through judging these awards that I also encountered Nataliya Meshchaninova’s Stories of a Life (translated from Russian by Fiona Bell), about girlhood and womanhood in post-Soviet Russia, which was like reading a series of group-text missives from your funniest, smartest, and saddest friend; Irene Solà’s When I Sing, Mountains Dance (translated from Catalan by Mara Faye Lethem), which is convincingly narrated, in turns, from the perspective of a roe-deer, mountains, and the ghosts of the Spanish Civil War, among other characters; and Agnes Bushell’s Monkey, maybe my favorite of them all, a madcap 600-page opus, set in nineteenth-century Russia, about the missing author of a missing manuscript. My favorite parts were about the author’s suffering mother.

By the springtime, I had decided to try and write a play adaptation of an essay of mine called “Ghosts.” I’d never written a play, and so I went on a play-reading binge, in which some of my favorites included Sarah DeLappe’s The Wolves, Annie Baker’s The Flick, and Clare Barron’s You Got Older. Then Pantheon bought an experimental essay collection of mine—it’ll be called Searches and will include “Ghosts”— and, for inspiration while finishing the collection, my first attempt at book-length creative nonfiction, I turned to reading some nonfiction with the kind of convention-bending vibes I wanted my collection to have: Ingrid Rojas Contreras’s The Man Who Could Move Clouds and Jami Lin Nakamura’s The Night Parade. I keep pressing both into people’s hands.

By the springtime, I had decided to try and write a play adaptation of an essay of mine called “Ghosts.” I’d never written a play, and so I went on a play-reading binge, in which some of my favorites included Sarah DeLappe’s The Wolves, Annie Baker’s The Flick, and Clare Barron’s You Got Older. Then Pantheon bought an experimental essay collection of mine—it’ll be called Searches and will include “Ghosts”— and, for inspiration while finishing the collection, my first attempt at book-length creative nonfiction, I turned to reading some nonfiction with the kind of convention-bending vibes I wanted my collection to have: Ingrid Rojas Contreras’s The Man Who Could Move Clouds and Jami Lin Nakamura’s The Night Parade. I keep pressing both into people’s hands.

In August, we returned to the U.S., which made it easier to order the books I’ve been wanting to read, through my beloved Poudre River Public Library District. Here, in no particular order, are several that blew my mind: Deena Mohamed’s Shubeik Lubeik, a graphic novel set in an alternate Egypt where people can buy and sell wishes; Lina Wolff’s Carnality (translated by Frank Perry), a novel set in Spain featuring, among other memorable characters, a dark-hearted nun with one of the wildest back stories I’ve ever read; Camille Dungy’s Soil, a gorgeous and subtle memoir about nurturing a garden in Fort Collins, where I happen to live; Catherine Lacey’s Biography of X, a mind-bending fictional biography of an art monster written by her widowed wife; and Justin Torres’s Blackouts, a thrilling puzzlebox of a novel about how identities, gay and otherwise, are performed.

In August, we returned to the U.S., which made it easier to order the books I’ve been wanting to read, through my beloved Poudre River Public Library District. Here, in no particular order, are several that blew my mind: Deena Mohamed’s Shubeik Lubeik, a graphic novel set in an alternate Egypt where people can buy and sell wishes; Lina Wolff’s Carnality (translated by Frank Perry), a novel set in Spain featuring, among other memorable characters, a dark-hearted nun with one of the wildest back stories I’ve ever read; Camille Dungy’s Soil, a gorgeous and subtle memoir about nurturing a garden in Fort Collins, where I happen to live; Catherine Lacey’s Biography of X, a mind-bending fictional biography of an art monster written by her widowed wife; and Justin Torres’s Blackouts, a thrilling puzzlebox of a novel about how identities, gay and otherwise, are performed.

As I write this, the year is coming to an end, and I’ve just finished the book tour for my second book, a story collection called This is Salvaged. Coming home exhausted, I was in the mood for a small and playful read. Whenever this happens, I go to the César Aira section of the library and grab whatever’s there; he’s written more than a 100 novels, last I checked, and I’ve never read one that’s anything less than genius. This time, I chose Dinner, which started out being about a man and his mother going to a friend’s house for dinner and ended up with a zombie apocalypse. I read that Aira never revises his work. He just writes. When he writes his way into a problem, he makes himself keep writing to try to find his way out of it. In this manner, he publishes several novels a year. Having spent about 13 years on each of my first two books, I want to try Aira’s approach with one of the next ones. I wonder if it’s possible for anyone, or only for Aira.

As I write this, the year is coming to an end, and I’ve just finished the book tour for my second book, a story collection called This is Salvaged. Coming home exhausted, I was in the mood for a small and playful read. Whenever this happens, I go to the César Aira section of the library and grab whatever’s there; he’s written more than a 100 novels, last I checked, and I’ve never read one that’s anything less than genius. This time, I chose Dinner, which started out being about a man and his mother going to a friend’s house for dinner and ended up with a zombie apocalypse. I read that Aira never revises his work. He just writes. When he writes his way into a problem, he makes himself keep writing to try to find his way out of it. In this manner, he publishes several novels a year. Having spent about 13 years on each of my first two books, I want to try Aira’s approach with one of the next ones. I wonder if it’s possible for anyone, or only for Aira.

Now the year is almost over. In 2024, I solemnly resolve, I’ll read more canonical white men.

More from A Year in Reading 2023

A Year in Reading Archives: 2022, 2021, 2020, 2019, 2018, 2017, 2016, 2015, 2014, 2013, 2012, 2011, 2010, 2009, 2008, 2007, 2006, 2005