Recently, my partner and I and a few friends gathered with somewhat ridiculous ceremony for a meeting of our book club devoted to E.M. Forster’s queer classic Maurice. That week, we were throwing a dinner party and screening the 1987 Merchant Ivory film adaptation starring James Wilby, Hugh Grant, and Rupert Graves. The whole party was animated by that high-concept, low-ambition, cockeyed wholesome glee that I associate (tellingly) with both adolescence and graduate school. The evening was themed almost to the point of Dadaism—the food prepared from Ismail Merchant’s 1994 celebrity cookbook Passionate Meals, unless brainstormed laboriously using the novel itself. (A dessert based on Alec’s stolen apricot? An homage to the chicken cutlet Risley uses to…demonstrate the tediousness of straight people, or something?) First orders of business were established over a lavish cheese plate: “We need to talk about all the hair-tousling,” someone said.

Recently, my partner and I and a few friends gathered with somewhat ridiculous ceremony for a meeting of our book club devoted to E.M. Forster’s queer classic Maurice. That week, we were throwing a dinner party and screening the 1987 Merchant Ivory film adaptation starring James Wilby, Hugh Grant, and Rupert Graves. The whole party was animated by that high-concept, low-ambition, cockeyed wholesome glee that I associate (tellingly) with both adolescence and graduate school. The evening was themed almost to the point of Dadaism—the food prepared from Ismail Merchant’s 1994 celebrity cookbook Passionate Meals, unless brainstormed laboriously using the novel itself. (A dessert based on Alec’s stolen apricot? An homage to the chicken cutlet Risley uses to…demonstrate the tediousness of straight people, or something?) First orders of business were established over a lavish cheese plate: “We need to talk about all the hair-tousling,” someone said.

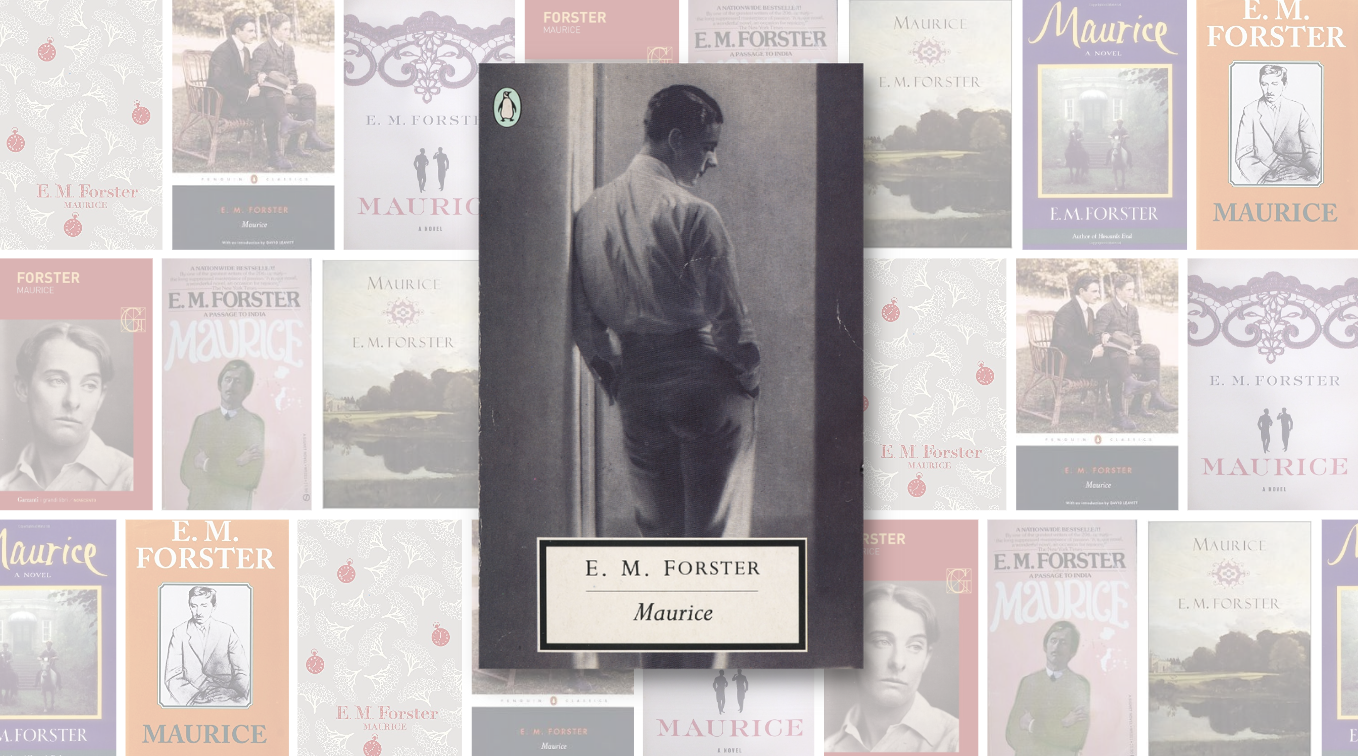

Maurice is, in many respects, a typical Forster novel: full of longing and poignant interiority, with heartbreak and ecstasy gleaned in unlikely places (such as, for instance, a lot of hair-tousling). Maurice Hall, destined for an unremarkable suburban life, is “saved” from this fate by his irrepressible (and not for lack of trying) homosexuality. Awakened and educated by his first beloved, Cambridge classmate Clive Durham (who knows a lot about the Greeks), Maurice is soon heartbroken when Clive “becomes normal” and marries—but he eventually finds love, and his own conception of identity and sexuality, with Clive’s under-gamekeeper Alec Scudder. In a triumphant climax Alec and Maurice escape into exile together, suffering no compromise with conventionality. (Clive, receiving this news, is short-circuited to the point of inanity.)

Maurice is ultimately a story of queer joy—a fantasy, given the era of its composition, but one bittersweetly grounded in reality: Alec and Maurice get their happy ending, but there is no illusion as to what they must sacrifice for it.

Our crew of queer households came to this dinner party somewhat battle-worn, collectively in the ambiguous space between celebration and simple exhaustion. As a group we were dragging ourselves through the final days before a high-stakes medical scan; a debut novel publication; a cross-country move; the end of a harrowing semester. I’d first conceived the idea for the gathering earlier this winter, as I’d tried and failed to concentrate on my dogeared copy of Maurice in my partner’s hospital room. At the time, waiting interminably for doctors to round, the idea of gathering with friends to laugh and eat and talk about a love story was its own kind of quietly unimaginable fantasy. And now, all these months later, here we were. A miracle.

Forster wrote Maurice from 1913 to 1914, following Howard’s End, as “the direct result” of his own homosexual awakening. He then held onto the manuscript for the rest of his life, revising based on the feedback of “carefully picked” friends as well as “useful personal experiences,” and watching the public attitude towards queerness “change from ignorance and terror to familiarity and contempt.” “Unless the Wolfenden Report [which eventually led to the decriminalization of homosexuality in England] becomes law,” Forster wrote then-privately in 1960, “[Maurice] will probably have to remain in manuscript. If it ended unhappily, which a lad dangling from a noose or with a suicide pact, all would be well…But the lovers get away unpunished.”

Forster wrote Maurice from 1913 to 1914, following Howard’s End, as “the direct result” of his own homosexual awakening. He then held onto the manuscript for the rest of his life, revising based on the feedback of “carefully picked” friends as well as “useful personal experiences,” and watching the public attitude towards queerness “change from ignorance and terror to familiarity and contempt.” “Unless the Wolfenden Report [which eventually led to the decriminalization of homosexuality in England] becomes law,” Forster wrote then-privately in 1960, “[Maurice] will probably have to remain in manuscript. If it ended unhappily, which a lad dangling from a noose or with a suicide pact, all would be well…But the lovers get away unpunished.”

In the end the book was published in 1971, a year after Forster’s death, bearing his haunting inscription “Begun 1913 / Finished 1914 / Dedicated to a Happier Year.” He had also left a handwritten note on the manuscript’s cover sheet: “Publishable—but is it worth it?”

“Oh god, it’s too real,” someone said, taking refuge in the cheese plate as we discussed Maurice and Clive’s first halting dormitory encounter. Someone else let out an offended gasp upon discovering that a line of dialogue had been revised in the film version from “Oh, rot” to “Don’t talk rubbish.” (“It changes everything!”) Someone else was already texting more friends a link to order the book.

Immediate critical reception of Maurice subjected Forster to subtler and more varied torments than criminal charges, with assessments ranging from a well-written but dated fairy tale (a pun few reviewers could resist) to “deeply embarrassing.” Cynthia Ozick’s 1971 review in Commentary magazine reaches a particularly high level of vitriol—as a professed admirer of Forster’s previous work, she finds Maurice to be “a disingenuous book, an infantile book,” a failed attempt to “attack and discredit society” and “the culmination of extensive fantasizing”—and compares Forster’s afterword, attesting to his own homosexuality, to “a suicide note.”

This element, in Ozick’s review as well as in general, is striking: the sense of mourning Forster’s legacy, as if the revelation of both his own sexuality and his treatment of it in fiction marred his status as one of the great novelists of the twentieth century. Still, even as critics seemed ready to ritually burn their well-thumbed copies of Howard’s End for guilt by association, many seemed disappointed that Maurice, with its lack of explicit sex, wasn’t gay enough. Philip Toynbee, writing in The Observer, grumbled that there was “nothing particularly homosexual about Maurice other than it happens to be about homosexuals.” Leaving aside the logical morass of this statement, the nearness of the missed point—that queer characters, and queer people in the real world, might have rich inner and outer lives beyond the mechanics of their sexual encounters—is painful; one can almost hear Forster’s famous imperative “Only connect” whizzing by overhead.

Unfortunately, complaints that an LGBTQ+ artist’s work is too queer, or not queer enough, or focuses on the wrong kind of queerness, are all still common. And though modernity has softened the violent objections to Maurice (which has found a devoted following in the half-century since its publication), snide reactions to both the novel itself and to Forster’s relationship with it have evolved with the times as well.

The 1987 film adaptation of Maurice, which our aggressively-themed dinner party lovingly heckled late into the evening, remains a touchstone of queer cinema. It also did no small part to legitimize Maurice as part of the Forster canon, following in step with Merchant Ivory’s adaptation of A Room with a View a few years before. But the duo’s usual screenwriter, Ruth Prawer Jhabvala, refused to collaborate on the film, reportedly calling Maurice “sub-Forster and sub-Ivory.” At the film’s release, Benedict Nightingale sniffed in the New York Times at the perceived inappropriateness of “so defiant a salute to homosexual passion” at the height of the AIDS epidemic. And in a 2018 BFI interview, when (after several minutes’ description of the gratitude of gay men for his work in Maurice) Hugh Grant allows that it was “certainly very brave” of Forster to have written the novel, James Wilby interjects “…although he never published it.” “Yeah, he hid it under his bed, didn’t he,” Grant says, and they end the interview with a chuckle at Forster’s expense—a fussy, fearful caricature, tinged slightly pathetic for not wanting to face obscenity charges, or caustic reviews damning his life alongside his work, or perhaps simply the chortling judgment of straight actors.

The 1987 film adaptation of Maurice, which our aggressively-themed dinner party lovingly heckled late into the evening, remains a touchstone of queer cinema. It also did no small part to legitimize Maurice as part of the Forster canon, following in step with Merchant Ivory’s adaptation of A Room with a View a few years before. But the duo’s usual screenwriter, Ruth Prawer Jhabvala, refused to collaborate on the film, reportedly calling Maurice “sub-Forster and sub-Ivory.” At the film’s release, Benedict Nightingale sniffed in the New York Times at the perceived inappropriateness of “so defiant a salute to homosexual passion” at the height of the AIDS epidemic. And in a 2018 BFI interview, when (after several minutes’ description of the gratitude of gay men for his work in Maurice) Hugh Grant allows that it was “certainly very brave” of Forster to have written the novel, James Wilby interjects “…although he never published it.” “Yeah, he hid it under his bed, didn’t he,” Grant says, and they end the interview with a chuckle at Forster’s expense—a fussy, fearful caricature, tinged slightly pathetic for not wanting to face obscenity charges, or caustic reviews damning his life alongside his work, or perhaps simply the chortling judgment of straight actors.

Publishable—but is it worth it?

Despite its long and difficult road to publication, Maurice is the product of passion and community. Forster kept it for 50 years, not in shameful hiding but in an active process of revision with the help of trusted friends. In 1952, some of those friends passed the manuscript from hand to hand in several stages, from Forster in London to Christopher Isherwood in Los Angeles, in order to protect it from being seized under the revived Comstock laws. Forster was part of a beloved and collaborative community, finding its way through adversity to a queer canon—as so many of us do. He was confident enough to dedicate Maurice the way he did; confident enough to hope that “a happier year” would come. And, by many objective measures, it has. But in this era of record-setting book bans, hateful legislation, and deteriorating media literacy, it strikes me that the cultivation of queer joy—as readers, as writers, and in the revelry of daily life—is still very much a matter of both fierce determination and mutual aid.

The planning of ridiculous dinner parties is, of course, not the vanguard of the resistance. But when delight and normalcy and self-expression and literary community are menaced—then yes, absolutely, ridiculous dinner parties have their role to play.

One of Maurice’s most pivotal plot points relies on a mundane coincidence: unseen workmen leave a ladder leaning against the side of Penge Hall overnight, providing Alec access to Maurice’s open window. This deus ex machina is part of what led some critics to decry the book as childish fantasy. But to me it has a different resonance—the plot doesn’t move because the workmen left the ladder. The plot moves because Alec climbs it; because Maurice lets him in.

There is something to be said for the meaning we make together—in celebration and catharsis, the shared joys and traumas of adolescence and graduate school and all of life’s messier transitions. We’re here to care for each other. We’re here to climb ladders and open windows. We’re here to pass each other’s manuscripts hand to hand, and to wait for each other’s doctors to round, and to make each other the most extravagantly themed cheese plates possible.

May each future year be a happier one.