September 5

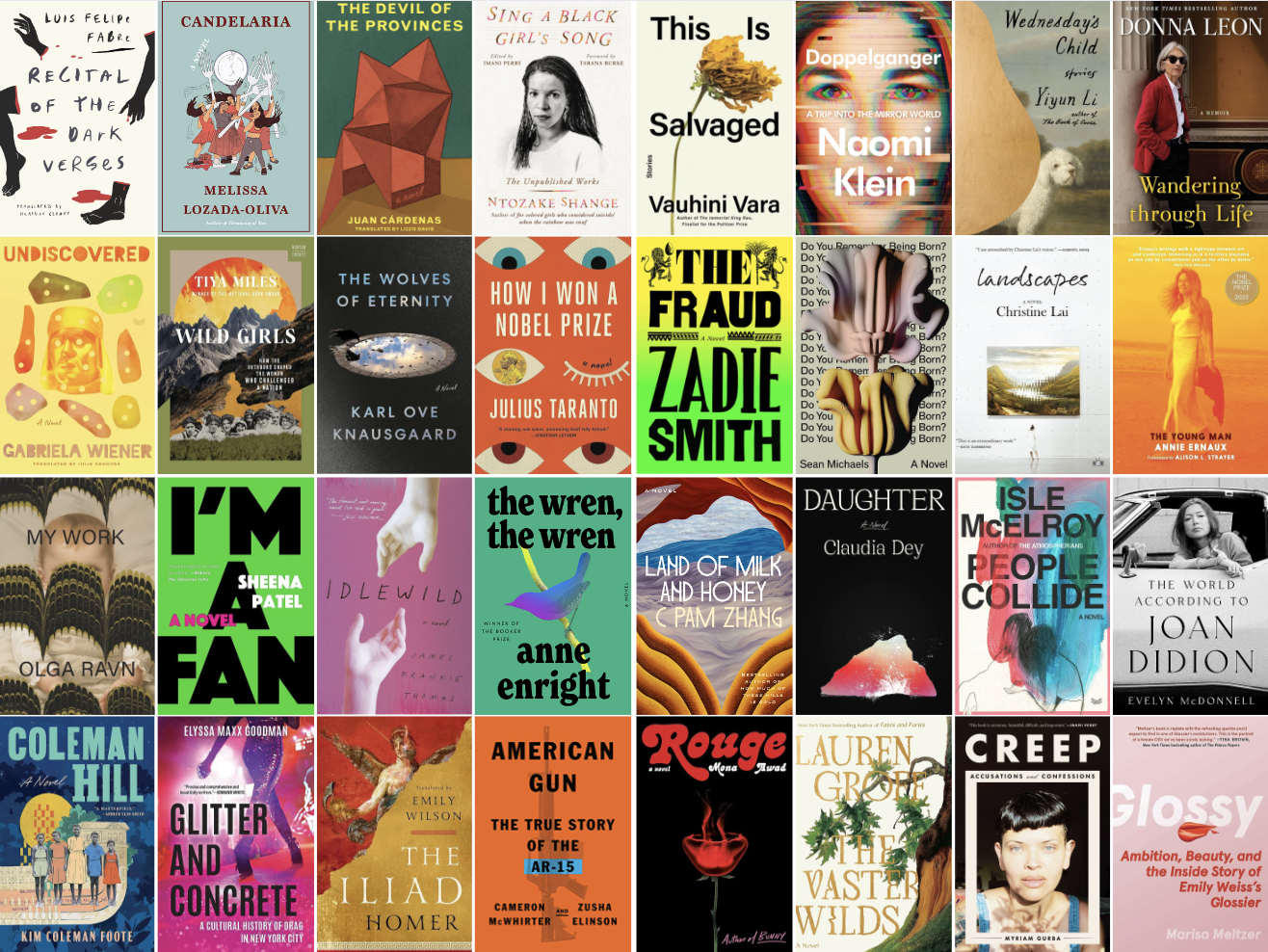

The Fraud by Zadie Smith [F]

by Zadie Smith [F]

Smith returns with her first novel since 2016’s Swing Time. Her first work of historical fiction, The Fraud, is set against a real legal trial over the inheritance of a sizable estate that divided Victorian England and, in the story, captivates the Scottish housekeeper of a famous novelist. Smith probes questions of truth and self-deception, fraudulence and authenticity, and what it means for something to be “real.” —LF

Coleman Hill by Kim Coleman Foote [F]

by Kim Coleman Foote [F]

Foote’s debut traces the entwined fates of two families during the Great Migration in a work of “biomythography,” a term coined by Audre Lorde. Andrew Sean Greer calls this, the inaugural title published by Sarah Jessica Parker‘s imprint, a “masterpiece” and Jacqueline Woodson says, “Once in a while, a writer comes along with a brilliance that stops the breath—Kim Coleman Foote is that writer.”

Wednesday’s Child by Yiyun Li [F]

by Yiyun Li [F]

Li’s been the sort of fiction writer other writers talk about over a few rounds with not-so-hushed awe since her first story collection hit shelves in 2005 and The New Yorker figured out that pretty much any piece she turned in was worth printing. She’s mostly known as a top-notch novelist now, but this return to short fiction—her first collection in 13 years!—should remind those not already passing copies of The Vagrants along to their friends like they’re introductory leaflets to some secret society why they fell in love with Li in the first place. —Allen Charles

I’m a Fan by Sheena Patel [F]

by Sheena Patel [F]

Patel’s debut is one of the first great social media novels (along, perhaps, with Patricia Lockwood‘s No One Is Talking About This). A bold, electric, and ruthless tale of sex, class, status, obsession, self-destruction, and the worst parts of being online, all told from the perspective of a beguiling unnamed narrator involved in a troubled romance, Rachel Yoder calls I’m a Fan “a scathing ode to the psychos and shitheads.” —SMS

Creep by Myriam Gurba [NF]

by Myriam Gurba [NF]

Gurba first captivated the literary world with her scathing essay on American Dirt, which was among first of what would soon be a tsunami of takedowns. In her equally ruthless and razor-sharp essay collection, Gurba considers the idea of “creeps”—both the noun and the verb—as an illuminating instrument for her cultural criticism. The blurber roster is astonishing and includes Luis Alberto Urrea, Imani Perry, Morgan Jerkins, and Rachel Kushner, who writes, “I loved Creep and already consider it essential reading, a California classic.” —SMS

Do You Remember Being Born? by Sean Michaels [F]

by Sean Michaels [F]

First off, can we hear a little commotion for the cover? I mean—stun-ning. But as for what’s inside: Michaels’s disturbingly topical novel follows an aging poet who agrees to collaborate with a Big Tech company’s poetry AI named Charlotte. I’m very much looking forward to this study of the intersections of art, labor, capital, and creativity—a book that I wish wasn’t as timely and relevant as it is. —SMS

September 12

Landscapes by Christine Lai [F]

Landscapes by Christine Lai [F]

In her debut novel, Lai—one of PW’s fall 2023 “writers to watch”—takes inspiration from Sebald to weave a tale of an archivist living and working in the English countryside in the near, climate-change-ravaged future. Art, feminism, and environmentalism collide in this cutting examination of ecological disaster and aesthetic ecstasy. —SMS

Idlewild by James Frankie Thomas [F]

by James Frankie Thomas [F]

I first encountered Thomas as a critic via his wry and razor-sharp review of the recent 1776 revival. So I’m excited to read his debut novel, the story of two estranged friends looking back on their formative years at a small Quaker high school in early-aughts lower Manhattan. Sarah Thankam Mathews and Kiley Reid both loved this one, and Pulitzer winner Paul Harding gave it a hearty “Bravo.” —SMS

Rouge by Mona Awad [F]

by Mona Awad [F]

The latest from Awad, the author of the hit 2020 novel Bunny, is pitched as Snow White meets Eyes Wide Shut—a horror-tinted gothic fairy tale about a lonely dress store clerk whose mother’s sudden death sends her in obsessive search of youth and beauty. Mary Karr herself says that she “couldn’t put it down.” —LF

The Devil of the Provinces by Juan Cárdenas, translated by Lizzie Davis [F]

by Juan Cárdenas, translated by Lizzie Davis [F]

In this tale of a son’s peculiar homecoming, Cárdenas (author of the fantastic 2015 novella Ornamental) mystifies with the story of a crime like no other. After 15 years away from home, a biologist returns to his Colombian village only to find it strikingly different from when he last left it. Amid a tangled web of conspiracy, nothing is as it seems. What happens, Cárdenas asks, when you get stuck in the one place to which you swore you’d never return? —DF

The Young Man by Annie Ernaux, translated by Alison Strayer [NF]

by Annie Ernaux, translated by Alison Strayer [NF]

In the Nobel winner’s latest, Ernaux reflects on an affair she had with a man in his twenties when she was in her fifties. The romance foregrounds various contradictions: why can men have younger lovers, but not women? How is it that Ernaux feels both aware of her age and ageless in the presence of her paramour? It’s a blessing, really, that there is still more Ernaux for Anglophone readers to discover and savor (even if the French did get to read this one a year ahead of us). —SMS

Daughter by Claudia Dey [F]

by Claudia Dey [F]

Dey’s latest novel, after 2018’s Heartbreaker, centers on a woman and her one-hit-wonder novelist father. Living in his shadow and caught in his orbit, she strives to make a life—and art—of her own. Raven Leilani and Miriam Toews are both fans, and Sheila Heti praises Dey for capturing “feelings and struggles I haven’t encountered in other novels. I loved this beautiful book.” —LF

Glitter and Concrete by Elyssa Maxx Goodman [NF]

by Elyssa Maxx Goodman [NF]

From the Jazz Age to Drag Race, journalist and drag historian Goodman offers a timely Technicolor history of drag in New York City and the role it’s played in both queer culture and urban life. Noted New Yorker (and excellent writer) Ada Calhoun calls this a “glamorous, giddy history” and “a love letter to New York City past and present.” —SMS

How I Won a Nobel Prize by Julius Taranto [F]

by Julius Taranto [F]

In Taranto’s debut novel, a grad student follows her disgraced mentor—a star professor embroiled in a sex scandal—to a university that is a safe harbor for scholars of ill repute. A crisis that tests her commitment, marriage, and conscience ensues. Jonathan Lethem calls this one work by “a stunning new talent, announcing itself fully formed”—indeed, a premise like this takes both deftness and confidence to pull off. Sounds like Taranto pulls it off and then some. —SMS

Glossy by Marisa Meltzer [NF]

by Marisa Meltzer [NF]

Cards on the table: I am, as the kids say, a Glossier girlie. But one need not be to pick up Glossy, a bombshell exposé and study of corporate feminism that reveals for the first time what exactly has gone down at Glossier under the leadership of Emily Weiss, who stepped down last year. If you don’t believe me, take Tina Brown‘s word for it; she calls this a book “the portrait of a female CEO we’ve been sorely lacking.” —SMS

The Vaster Wilds by Lauren Groff [F]

by Lauren Groff [F]

Groff follows up her 2021 novel Matrix with another work of historical fiction, trading her 12th-century monastery for a Jamestown-esque colonial settlement. When a servant girl escapes to the wilderness, she’s forced to rethink the laws of civilization and colonialism that she’s internalized. Part-adventure, part-fable, classic Groff. —LF

Doppelganger by Naomi Klein [NF]

by Naomi Klein [NF]

The impetus for this book is actually kind of funny—Klein, upset that she keeps getting confused with the respected-feminist-writer-turned-ostracized-conspiracy-theorist Naomi Wolf, looked into the nature of digital doppelgängers. But that led her down a far more fruitful and fascinating path toward questions of identity, psychology, democracy, communication in the modern age, and, ultimately, this book. And it’s Judith Butler-approved to boot! —SMS

Sing a Black Girl’s Song by Ntozake Shange, edited by Imani Perry [NF]

by Ntozake Shange, edited by Imani Perry [NF]

This posthumous collection of unpublished work by the visionary Shange, edited by Imani Perry and with a foreword by Tarana Burke, introduces readers to never-before-seen essays, plays, and poems by the foundational writer behind the paradigm-shifting 1975 play for colored girls who considered suicide/when the rainbow was enuf. Shange, who died in 2018, was an intellectual giant, in conversation with writers like Morrison and Walker, who never quite got her due in life. —SMS

Betty Friedan: Magnificent Disrupter by Rachel Shteir [NF]

by Rachel Shteir [NF]

Friedan‘s legacy is complicated and sometimes contradictory, and in the first biography of Friedan in more than 20 years, Shteir tries to capture her subject in all her (often frustrating) complexity. A myopic and mercurial crusader, whose devotion was sincere and priorities warped, Friedan deserves a biography that can capture her fullness. And with her rigorous research, interviews, and archival dives, Shteir looks up to the task. —SMS

September 19

Candelaria by Melissa Lozada-Oliva [F]

by Melissa Lozada-Oliva [F]

Lozada-Oliva’s follow-up to her wonderful novel-in-verse Dreaming of You was pitched to me as Julia Alvarez’s How the Garcia Girls Lost Their Accents meets Cormac McCarthy’s The Road. Needless to say, it got my attention. Cults, earthquakes, and a mysterious buffet inside a mall pepper the daunting journey that one woman must take to save her granddaughters and possibly the world. —SMS

Wild Girls by Tiya Miles [NF]

by Tiya Miles [NF]

Miles, a brilliant historian and author of the National Book Award-winning All That She Carried, looks at trailblazing women throughout U.S. history, from Harriet Tubman to Louisa May Alcott to Dolores Huerta, to consider how their girlhood experiences outdoors shaped their lives and work. Miles is a wonderful writer, rigorous researcher, and visionary scholar, and here she takes a totally unique (and characteristically ingenious) perspective on how the natural world influenced many of our most consequential women thinkers and leaders. —SMS

The Book of (More) Delights by Ross Gay [NF]

by Ross Gay [NF]

Gay is back with a follow-up to his tender and uplifting 2019 book The Book of Delights. I’m admittedly curious to see what other delights he could possibly have in store—the first book was a perfect little gem that didn’t exactly demand a sequel—but I trust Gay completely as both a charming prose stylist, a seasoned practitioner of noticing, and a keen observer of the quotidian joys that are all around us. —SMS

Bartleby and Me by Gay Talese [NF]

by Gay Talese [NF]

Sixty years ago, Talese wrote in Esquire that “New York is a city of things unnoticed.” He spent the next six decades doing quite a bit of noticing, chronicling the people (and places and moments) that make the city what it is. In his latest, he remembers the “nobodies” that he’s profiled over the course of his career, the cast of characters perhaps who are not as recognizable as, say, Sinatra or Ali, but nevertheless essential threads in our cultural fabric. —SMS

The Wren, the Wren by Anne Enright [F]

by Anne Enright [F]

Enright, best known for her 2007 Booker Prize-winning novel The Gathering, follows three generations of women who contend with their inheritances from one man—a celebrated Irish poet—that continue to shape their lives. A women-centered family portrait punctuated with lyrical poems, Sally Rooney calls The Wren, The Wren “a magnificent novel.” —LF

The Wolves of Eternity by Karl Ove Knausgaard, translated by Martin Aitken [F]

by Karl Ove Knausgaard, translated by Martin Aitken [F]

Knausgaard returns with another dazzling tome on the human condition, narrated from the dual perspectives of long-lost siblings struggling with the timeless conundrum of responsibility vs. self-actualization. Here Knausgaard fashions his own theories of what it is to love, to lose, to live, and be part of a family. Patricia Lockwood says it best: “Just as we begin to wonder where he is taking us, whether he is capable, he gets us there.” —DF

Wandering Through Life by Donna Leon [NF]

by Donna Leon [NF]

Leon’s Commissario Brunetti books—a Venice-set mystery series with 31 installments (so far)—made her a literary legend. But she’s largely stayed out of the spotlight—until now. In her eighties, Leon looks back on her own adventurous life, traveling the world, settling in Italy, and discovering her passion and aptitude for writing. I’ll be honest, the cover alone sold me here—this is exactly what I want to look when I’m 80: sunglasses, bob, blazer, blindingly cool. You just know she’s got some good stories in her bandoleer. —SMS

50 Years of Ms. edited by Katherine Spillar, foreword by Gloria Steinem [NF]

edited by Katherine Spillar, foreword by Gloria Steinem [NF]

When it launched in 1971, Ms. Magazine was one of the most radical publications on the market, broaching subjects that had long been kept out of popular discourse. With Steinem at its helm, the feminist magazine was essential reading for the era of women’s liberation. This collection of mag’s best writing includes work by Toni Morrison, Joy Harjo, Audre Lorde, bell hooks, Allison Bechdel, and many more. Essential reading for anyone looking to understand the radical roots of mainstream feminism. —SMS

Recital of the Dark Verses by Luis Felipe Fabre, translated by Heather Cleary [F]

by Luis Felipe Fabre, translated by Heather Cleary [F]

Translated by the great Heather Cleary, the debut novel by Fabre made waves in Mexico, earning him the prestigious Elena Poniatowska Prize. (By the way, if you haven’t read Poniatowska, read Poniatowska.) Based on the true story of the theft of the body of Saint John of the Cross from a monastery in Ubeda. Part road-trip novel, part coming-of-age tale, part slapstick comedy, Recital of the Dark Verses is bound to make a splash with Anglophone readers. —SMS

Love in a Time of Hate by Florian Illies, translated by Simon Pare [NF]

by Florian Illies, translated by Simon Pare [NF]

Surely there’s nothing like a book about a bevy of emotionally damaged creative geniuses staring down what must have seemed to them like the end of the world to rile up the sort of lit dork who’s made it this far down this list. This one seems promising, cramming practically every pre-war fave, problematic or no—Sartre and de Beauvoir! Dietrich and Nabokov! Arendt and Benjamin! Dalí and Picasso!—into a history of artists caught between financial collapse and rising fascist violence. Anyway, sound familiar? —AC

September 26

Land of Milk and Honey by C Pam Zhang [F]

by C Pam Zhang [F]

The followup to Zhang’s debut novel How Much of These Hills Is Gold considers the ethics of seeking pleasure against the backdrop of a world in disarray. As environmental catastrophe looms, a chef escapes the city to take a job in an idyllic mountaintop colony, where nothing is as it seems. Among the novel’s fans are Raven Leilani, Roxane Gay, and Gabrielle Zevin, who declares, “It’s rare to read anything that feels this unique.” —LF

My Work by Olga Ravn, translated by Sophia Hersi Smith and Jennifer Russell [F]

by Olga Ravn, translated by Sophia Hersi Smith and Jennifer Russell [F]

I’ve been a fan of Ravn’s since I read her bleak, brilliant sci-fi novella The Employees, translated by Martin Aitken. Her latest, My Work, explores childbirth and motherhood by mixing different literary forms—fiction, essay, poetry, memoir, letters—with her signature experimental flair. I’m especially interested to read Ravn via Smith and Russell, who together have previously translated Tove Ditlevsen. —SMS

Jane Campion on Jane Campion by Michel Ciment [NF]

by Michel Ciment [NF]

I’ll just let Harvey Keitel blurb this one: “Jane Campion is a goddess, and it’s difficult for a mere mortal to talk about a goddess. I fear being struck by lightning bolts.” —SMS

People Collide by Isle McElroy [F]

by Isle McElroy [F]

McElroy’s sophomore novel, which comes on the heels of their debut The Atmospherians, chronicles a husband and wife who switch bodies, only for one of them to disappear without a trace. A fresh take on a classic trope, propelling this speculative story is the question of how this metamorphosis could transform their fraught union. Torrey Peters writes, “I predict Isle McElroy’s People Collide will inaugurate an entire genre.” —LF

This Is Salvaged by Vauhini Vara [F]

by Vauhini Vara [F]

Vara’s story collection, which follows her Pulitzer-nominated debut novel The Immortal King Rao, examines human relationships and our intrinsic yearning for connection. The book’s all-star roster of blurbers includes Deesha Philyaw, Danielle Evans, Elizabeth McCracken, and Lauren Groff, and Pulitzer winner Andrew Sean Greer says This is Salvaged is “for readers who need clarity and hope–that is to say: everybody.” —LA

The World According to Joan Didion by Evelyn McDonnell [NF]

by Evelyn McDonnell [NF]

Since her death in late 2021, Didion has been iconized (i.e. flattened, simplified) even more than she was in life. She was, of course, cold and beautiful and utterly California—but there was much more to her than that. So it’s reassuring to hear the brilliant Hua Hsu report that McDonnell’s new volume on Didion “avoids simple platitudes, approaching the great writer with a fierce, probing intelligence.” Didion deserves no less. —SMS

American Gun by Cameron McWhirter and Zusha Elinson [F]

by Cameron McWhirter and Zusha Elinson [F]

With mass shootings now endemic to American life, two veteran Wall Street Journal journalists look at one of the most common culprits—the AR-15—to figure out how we got here. Tracing the weapon’s history and embrace by the gun industry, the duo reveals the various financial, political, and cultural interests at play in the horrific assent of a killing machine. Esteemed MLK biographer Jonathan Eig calls this “social history at its finest.” —SMS

Undiscovered by Gabriela Wiener, translated by Julia Sanches [F]

by Gabriela Wiener, translated by Julia Sanches [F]

In this work of autofiction, Weiner—a respected Peruvian journalist and writer—considers the legacy of imperialism through one woman’s family ties to both the colonized and colonizers. A study of the intersections of the personal and historical, violence and race, love and desire, I think/hope Undiscovered will be Weiner’s breakthrough moment for Anglophone readers—the blurb from Valeria Luiselli is certainly a good sign. —SMS

The Iliad by Homer, translated by Emily Wilson [F]

by Homer, translated by Emily Wilson [F]

Wilson made waves in 2017 as the first woman to publish an English-language translation of The Odyssey, with its controversial opening line: “Tell me about a complicated man.” She’s been outspoken about the role her womanhood does and doesn’t play in translating, telling the LA Review of Books, “The stylistic and hermeneutic choices I make as a translator aren’t predetermined by my gender identity.” Still, there’s something exciting about experiencing Homer via a woman’s translation, which until now had not even been an option for Anglophone readers. I’m looking forward to Wilson’s take on The Iliad. —SMS