This January, I finally read Jean Rhys’s Good Morning, Midnight, a grim and angry novel to begin a grim and angry year. First published in 1939, the frisson of suppressed brutality its narrator encounters everywhere has started to feel claustrophobically familiar now. In some ways, it’s a novel about precariousness — economic, social, psychological, historical — and about its exhausting effects on the human soul. I think Rhys had a special genius for understanding the subtle relationship between her characters’ inner lives and the grinding machinery of world history. It’s a gift I searched for often in my reading this year.

This January, I finally read Jean Rhys’s Good Morning, Midnight, a grim and angry novel to begin a grim and angry year. First published in 1939, the frisson of suppressed brutality its narrator encounters everywhere has started to feel claustrophobically familiar now. In some ways, it’s a novel about precariousness — economic, social, psychological, historical — and about its exhausting effects on the human soul. I think Rhys had a special genius for understanding the subtle relationship between her characters’ inner lives and the grinding machinery of world history. It’s a gift I searched for often in my reading this year.

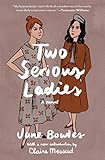

I found it again in Jane Bowles, whose singular novel Two Serious Ladies (1943) I discovered this spring. Written in a kind of flat and gloriously weird prose, the novel loosely follows two women as they throw themselves into destructive crusades against social convention. The private lives of individuals are probably always subject to the public machinations of power, but maybe this is most obvious in periods of historical crisis. At one point in the novel, overhearing a conversation between two young Marxist radicals, the protagonist Miss Goering remarks: “You…are interested in winning a very correct and intelligent fight. I am far more interested in what is making this fight so hard to win.”

I found it again in Jane Bowles, whose singular novel Two Serious Ladies (1943) I discovered this spring. Written in a kind of flat and gloriously weird prose, the novel loosely follows two women as they throw themselves into destructive crusades against social convention. The private lives of individuals are probably always subject to the public machinations of power, but maybe this is most obvious in periods of historical crisis. At one point in the novel, overhearing a conversation between two young Marxist radicals, the protagonist Miss Goering remarks: “You…are interested in winning a very correct and intelligent fight. I am far more interested in what is making this fight so hard to win.”

Margaret Drabble’s Jerusalem the Golden (1967) is a quiet, intimate novel about friendship, sex, and social class. I read it under beating sun in Porto this summer and it charmed me almost to tears. Featuring a wry, self-aware protagonist, a glamorous cast of secondary characters, and cheerfully staunch leftist politics, it seems to me an unfortunately neglected novel of mid-20th-century Britain, and a forerunner of much of the great feminist fiction that followed.

Margaret Drabble’s Jerusalem the Golden (1967) is a quiet, intimate novel about friendship, sex, and social class. I read it under beating sun in Porto this summer and it charmed me almost to tears. Featuring a wry, self-aware protagonist, a glamorous cast of secondary characters, and cheerfully staunch leftist politics, it seems to me an unfortunately neglected novel of mid-20th-century Britain, and a forerunner of much of the great feminist fiction that followed.

On the recommendation of a friend, I picked up a copy of Alejandro Zambra’s My Documents (2015, translated by Megan McDowell), a startling and gorgeous collection of short fiction. Zambra’s observations are forensic, his prose is masterfully direct, and his interrogation of form, voice, and identity feels urgent rather than playful. I practically swallowed the book whole. I’m already looking forward to reading the rest of Zambra’s work, starting right now with his new book Multiple Choice (2016).

At one point in Good Morning, Midnight, Rhys’s narrator declares: “I want a long, calm book about people with large incomes — a book like a flat green meadow and the sheep feeding in it.” I confess that I shared this desire often in 2016. I reread not only Jane Austen’s Northanger Abbey, but also Pride and Prejudice and Persuasion, as well as Charles Dickens’s Great Expectations. A wealth of writing exists on all these novels and I have nothing insightful to add here, except that they consoled me somewhat while the world descended into catastrophe. Great writing can do more, but sometimes consolation is no small task.

At one point in Good Morning, Midnight, Rhys’s narrator declares: “I want a long, calm book about people with large incomes — a book like a flat green meadow and the sheep feeding in it.” I confess that I shared this desire often in 2016. I reread not only Jane Austen’s Northanger Abbey, but also Pride and Prejudice and Persuasion, as well as Charles Dickens’s Great Expectations. A wealth of writing exists on all these novels and I have nothing insightful to add here, except that they consoled me somewhat while the world descended into catastrophe. Great writing can do more, but sometimes consolation is no small task.

More from A Year in Reading 2016

Don’t miss: A Year in Reading 2015, 2014, 2013, 2012, 2011, 2010, 2009, 2008, 2007, 2006, 2005