1.

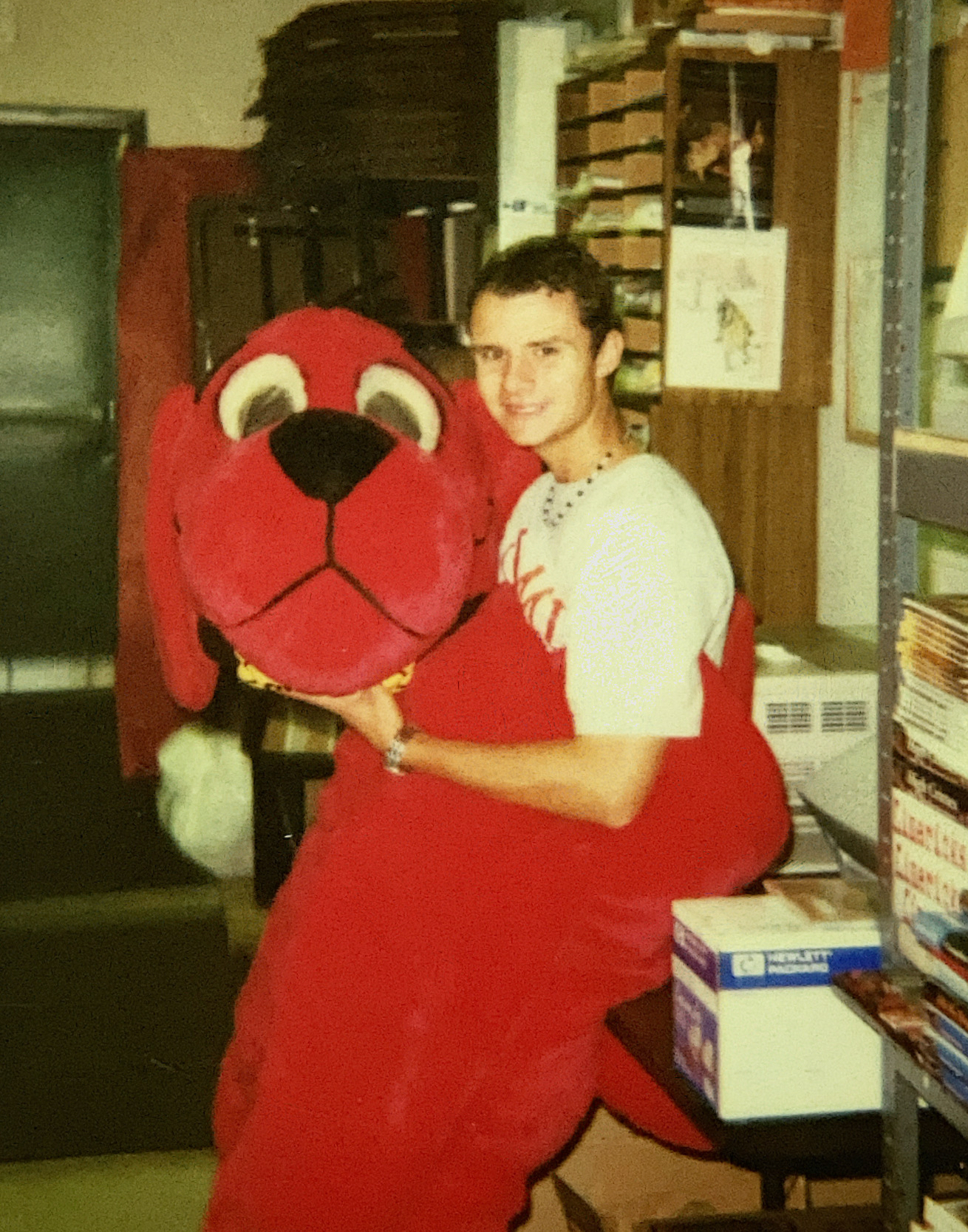

A few months after being hired as a bookseller at the second largest independent bookstore in Indiana, I received an unexpected promotion—to Easter Bunny.

I stared at the bunny suit and accompanying head crushed into the crate in the bookstore’s backroom. “So you want me to put that on?” I said, turning to my boss. My boss—a man in his late 20s—nodded.

“Why me?”

“I don’t know,” he said, grinning. “You look about the right size.”

It was the spring of 2001. I was 16, a sophomore, and, as it turned out, about the right size for the entire menagerie of Saturday morning story hour costumes. Following my stint as the Easter Bunny, I became Clifford the Big Red Dog, Angelina the Ballerina, Franklin the Turtle, Curious George, and Spot, amid a host of other children’s books characters. Since the clunky costumes didn’t allow much in the way of maneuverability, I relied on Sherry—the store’s story time specialist—to guide me by the furry hand from the backroom to the throne in the children’s section. No matter the costume, as soon as I turned the corner, the children greeted me with an enthusiasm generally reserved for Barney and Big Bird. While Sherry read the story, I summoned the miming skills of Marcel Marceau, dramatically reacting to every page. When the story ended, the children engaged in a little light rioting in their attempt to hop onto my lap for a photo.

“Sm-ile!” Sherry called, snapping the photos and allowing the images to unspool from the Polaroid camera. I sweated a river inside that suit until, at last, the line of children reached its end.

“Nice work,” my boss said, removing my head and peeling me out of the suit. “And thanks.”

“No problem,” I replied. I’d begged my way into this job in the hopes that it might lead me closer to a literary life. And it would. Eventually. One character costume at a time.

2.

Long before serving as the bookstore’s various mascots, I was its most loyal customer. I’d grown up in its overstuffed chairs, whittling away my elementary school years with stacks of chapter books piled high alongside me. Over time, the booksellers got to know me; I was the earnest young kid who always reshelved the books he didn’t buy. In some ways, I was a different store mascot then—no costume required.

To celebrate the end of my seventh-grade school year, my mother drove me to the bookstore and said, “You can pick out any book you want.” While my friends spent the first night of summer at the movies, I spent mine running my finger along the spines of books as if performing some divination.

Once, buried in the science fiction section I noticed an unassuming book by Ray Bradbury, whose short story, “The Fog Horn,” we’d read in English class earlier that year. I pulled Dandelion Wine from the shelf and read the back copy. “The summer of ’28 was a vintage season for a growing boy,” it read. “A summer of green apple trees, mowed lawns, and new sneakers. Of half-burnt firecrackers, of gathering dandelions…”

I was sold, not only by the poetic flourishes of the subject but the timing, too. The book began on the first day of summer 1928—precisely 70 years from the moment in which I then lived. Surely it was a sign, a bit of bibliomancy to direct me to whatever came next. I made my way to the register that I would one day operate.

“Great choice,” the bookseller said, ringing me up and returning the book. “When you’re done, come back and tell me what you think.”

“I will,” I promised.

3.

In 2001, Americans were reading three books: Who Moved My Cheese, The Prayer of Jabez, and John Adams. I knew this because, when I wasn’t “in character,” it was my job to shelve them directly across from the registers. I’d face their covers out, giving customers a visual reminder of what they’d seen on the Today Show or in the pages of People magazine. Of course, readers got their recommendations from at least one other source, Oprah Winfrey, whose book selections catapulted more than a few titles—Icy Sparks, Cane River, Stolen Lives—to the top of the bestseller lists. I never read any of them, though many people did. Or at least many people bought them, paged through them, and lugged them to the book club and back. At which point Oprah would make her next selection and the cycle repeated.

I never begrudged this brand of book buyer. True, their literary preferences were decided by a talk show host, but at least that talk show host got them through the door. And without their willingness to plunk down $24.95 a dozen times a year, we’d have never survived the big box bookstores, whose daily encroachment threatened our survival. I didn’t much care if the books were any good; I just wondered what it must feel like to hold in your hands a book you’d written yourself. I wasn’t thinking like a reader, I was thinking like a writer.

For the remainder of my high school career, I began acting like a writer, too—penning failed story after failed story when I wasn’t at school or at the store. And for nearly three years, it seemed I was always at the store. I worked weekends, in addition to one or two weeknights. If my work schedule wreaked havoc on my social life, I can’t recall. What I do remember were the perks: getting paid slightly more than minimum wage to borrow books, chat up fellow readers, and brush shoulders with every author who stepped through our doors. Hardly a week passed when some author didn’t. In my first month, I worked events featuring Dave Pelzer and Bill Bryson, and marveled at their standing-room-only crowds. I set up the chairs and tore down the chairs and peddled their books as best I could. The process repeated itself for James Patterson, Jim Davis, David Almond, and so many others.

Most nights, I maintained some semblance of professionalism, but when I met John Updike, I was too starstruck to manage much beyond the idiotic ramblings of a 17-year-old. “I…I saw your cameo on The Simpsons,” I told him. Updike pondered this and then released his tight New England laugh.

“That’s right,” Updike said. “I did do that, didn’t I?”

Yes, I confirmed. He had.

4.

One night in 2001, the author Peter Jenkins, who’d famously walked across America, stuck around after closing to sign a few stacks of books. I’d been sequestered behind the register for most of his talk, though now that the doors were locked and the customers had gone home, I lingered in his field of vision, hopeful for a conversation. I’d just finished cleaning the bathrooms, my body reeking of lemon-scented disinfectant and toilet bowl cleaner. If he noticed, he offered no indication. Instead, he signed the last of his books, then turned toward me and introduced himself. For 15 minutes, we small-talked near the gas fireplace in the center of the store, surrounded by hundreds of travel books.

“Do you write?” Jenkins asked me.

“I try,” I said.

“Well, what do you write about?”

Nobody had ever asked me that, and whatever answer I managed lacked conviction. My boss was in the backroom counting the drawers, so I took it upon myself to walk the author to the front of the store and send him off. He waved, wished me the best with my writing, and then walked toward his car. I thought: The man now walking before me once walked across America. But even more impressive, he’d written a book about it.

5.

One night, as the rain drummed down upon the store’s skylight, I hid in the fiction section and read a collection of stories by a writer named Jhumpa Lahiri. I was so deeply immersed in the collection’s opening story that I didn’t hear my coworker buzz me over the intercom. Before that night, I’d never heard Lahiri’s name; I knew nothing of her work. But the story of Shoba and Shukamar—and their confessions to one another under cover of darkness—so moved me that I became numb to the world around me. I sunk to the floor alongside the other L- authors—Tim LaHaye, Dennis Lehane, Laura Lippman—and tried to understand how a writer could make me care so deeply about people I’d never met.

“Where on earth were you?” my co-worker asked upon my eventual return to the register.

“I don’t know,” I said. “Somewhere else.”

6.

Four years after purchasing Ray Bradbury’s Dandelion Wine, I received a letter from the author in the mail. I’d written an essay on Bradbury which, much to my astonishment, had won first prize in a national contest. I was working a late shift at the bookstore when my mother hand delivered it.

“This came for you,” she said, pointing to the return address.

Standing at the same register where I’d purchased my first Bradbury book, I opened the envelope. Ray Bradbury had read my essay, his letter informed me, and he thought it “one of the finest” essays he’d ever read. He promised to keep it in his desk drawer “as a permanent piece of literature for me to read from time to time.”

That night, I shelved the books twice as fast. Memoir, history, psychology, reference—the books found their place in record time. I directed customers to The Lovely Bones, The Da Vinci Code, The Corrections—whatever they wanted. It took every ounce of restraint I had to keep from pulling Bradbury’s letter from my pocket and sharing it with every customer. See this? I wanted to shout. Someone out there was listening! Next time somebody asked me what I was writing, I’d have an answer.

That night, I shelved the books twice as fast. Memoir, history, psychology, reference—the books found their place in record time. I directed customers to The Lovely Bones, The Da Vinci Code, The Corrections—whatever they wanted. It took every ounce of restraint I had to keep from pulling Bradbury’s letter from my pocket and sharing it with every customer. See this? I wanted to shout. Someone out there was listening! Next time somebody asked me what I was writing, I’d have an answer.

7.

When Lois Lowry was in town, the bookstore’s owner—who was aware of my literary ambitions—generously assigned me the task of assisting Lowry with her autographs. My job was simple: open each book to the proper page and let her do the work. At that point in my life, Lowry’s The Giver was one of the most consequential books. It was the first book that felt like it was taking me seriously as a reader. It refused merely to entertain.

When Lois Lowry was in town, the bookstore’s owner—who was aware of my literary ambitions—generously assigned me the task of assisting Lowry with her autographs. My job was simple: open each book to the proper page and let her do the work. At that point in my life, Lowry’s The Giver was one of the most consequential books. It was the first book that felt like it was taking me seriously as a reader. It refused merely to entertain.

Since the bookstore owner hadn’t explicitly prohibited me from doing anything dumb, I did something rather dumb. Upon learning that I was a writer, too, Lowry made the mistake of asking the same question Peter Jenkins had asked, only this time I was ready. What was I writing?

“Mostly this,” I said, pulling forth from my backpack my two-hundred-page manuscript. “You can have it if you want,” I said. “I’ve got other copies.”

A polite “thanks but no thanks” was in order. An impolite, “Leave me alone, kid,” would have been warranted, too. Instead, she summoned some wellspring of generosity, and said, “Thank you. I look forward to reading it on the plane.”

A few years back, after a young writer handed me a similarly sized unsolicited manuscript, I reached out to Lois Lowry to beg forgiveness for my faux pax. “I don’t know if you remember me,” I began in an email, “but back in 2002 or so, I handed you my novel….” She did not remember me. Thank God. “But I will tell you that I do treasure each individual encounter,” she added. “And I’m glad you’ve treasured the memory of it as well.”

8.

Later, after publishing a few books of my own, I returned to my hometown to give a reading at the local library. Following the presentation, I glanced up to see the bookstore owner who, 15 years prior, had the bad sense to trust me not to pass off my manuscript to Lois Lowry. I didn’t know what to say to the man. How to thank the person who created the space for some high school kid to get a taste of the literary life?

“I wouldn’t be here if it wasn’t for you,” I finally managed.

“Oh, it was nothing,” he replied.

“It was something,” I said. “Meeting all those authors and shelving all those books, it allowed me to be a part of things.”

Only a handful of people remember how the rain drummed atop the store’s skylight. And how when you looked up in the right light, you could see a hint of your reflection staring back. We shook hands, and I never saw him again. Moments later, I was approached by a teenaged student who informed me he was a writer, too. I took the risk; I asked the question.

“Oh yeah? And what do you write?”

9.

A few summers back, I founded an arts camp for 14-to-18-year-old artists in five disciplines. I did it not because I am a glutton for punishment, but because only now, in middle age, do I understand the impact seasoned artists have had on my life. Not just the aforementioned writers but also the local journalists, the English teachers, the librarians. Those people who helped me understand that there are plenty of paths to the literary life, and only sometimes does that path involve costumes.

When I watch young artists interact with their artist mentors at camp, it all seems far more casual. Either their artistic heroes are humbler, or today’s young artists are harder to impress. If they want to be starstruck, the young artists scroll TikTok. But if they want to learn about color, shape, and how to craft a line, they pocket their phones and turn to their mentors. They are direct, pragmatic, and unafraid. They are what I wish I’d been.

10.

On the night Harry Potter and the Order of the Phoenix was released, the bookstore stayed open late. Hundreds of people packed the store, many of them wearing cloaks and scarves, all of them wielding wands. Though I was fully aware of the Harry Potter phenomena, I’d underestimated the commitment of the series’s superfans. They trembled with anticipation, sheer joy flooding their faces as they dreamed up spells to speed up the hands on their watches.

On the night Harry Potter and the Order of the Phoenix was released, the bookstore stayed open late. Hundreds of people packed the store, many of them wearing cloaks and scarves, all of them wielding wands. Though I was fully aware of the Harry Potter phenomena, I’d underestimated the commitment of the series’s superfans. They trembled with anticipation, sheer joy flooding their faces as they dreamed up spells to speed up the hands on their watches.

Legally, we weren’t allowed to sell the books until midnight. And so, when the hour struck, I joined a parade of booksellers to wheel out the book carts. The superfans—children and adults alike—nearly tore my clothes as they threw their bodies toward those carts, snatching up copies before I even made it to the front of the store. It was the closest I ever came to being a rockstar.

Today, it seems impossible: that there was a time when hundreds of people would gather, stay up late, and squeal at the prospect of getting their hands on a long-anticipated book. It was a communal event, an occasion, something you marked on your calendar. Book buyers have since foregone such occasions in favor of convenience: a click, a swipe, and the book’s delivered straight to your door. At which point the solitary act of buying the book can be accompanied by the solitary act of reading. The bookseller is lost in the process. As is the budding writer.

11.

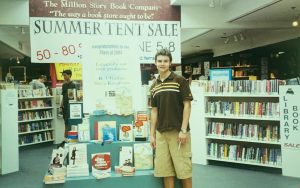

“Smi-ile,” my mother called.

It was May 2003, days before I received my high school diploma. I was at the bookstore, posing before a giant display of graduation books (Oh, The Places You’ll Go, The Healthy College Cookbook). Directly above me was a sign with my name on it, congratulating me on my impending graduation. By then, I’d been working at the bookstore for years, and the people there had become family. Not just my coworkers (one of whom would be a groomsman at my wedding) but also the customers (one of whom would attend that wedding).

It was May 2003, days before I received my high school diploma. I was at the bookstore, posing before a giant display of graduation books (Oh, The Places You’ll Go, The Healthy College Cookbook). Directly above me was a sign with my name on it, congratulating me on my impending graduation. By then, I’d been working at the bookstore for years, and the people there had become family. Not just my coworkers (one of whom would be a groomsman at my wedding) but also the customers (one of whom would attend that wedding).

By August, the bookstore would shutter its doors for good—the latest casualty of the big box bookstores. But even if our store hadn’t closed—even if we’d survived our brick-and-mortar competition—my time donning character costumes had ended. I’d move to Illinois in early September to study English and creative writing at a small liberal arts college. And while the next four years were vital to my writing development, they were not nearly as important as the three years that came before. Amid all those interactions with all those writers, I came to learn one essential truth: Writers were people just like me.

Too-cool-for-school senior that I was, I offered my mother and her camera no more than a two-second grin. Just long enough to snap a shot of me in my natural environment: an 18-year-old in cargo shorts and a Hollister shirt. Staring at the photo today, I notice something else: a pen dangling from my writing hand. It’s the only bookstore photo I’ve got when I’m not in costume. And it’s the photo that captures the most.