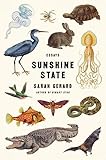

Sarah Gerard arrived on the literary scene with her collection of essays, Sunshine State, three years ago, garnering much praise and being hailed as a “writer to watch.” Her debut novel, Binary Star, received similar praise two years earlier. The Florida-born writer just published her highly anticipated novel True Love, but not before the book made its presence known vis-a-vis every book preview under the sun. And for good reason.

Nina, a struggling writer, college drop-out, and professional bad-decision-maker, forgoes the muted suburbs of Florida for the calamity of New York City in pursuit of the kind of love that will countervail the past she’s left behind. Her search for fulfillment is anything but linear, oscillating between the various people in her life like her mother, a narcissistic lesbian living in a polycule; Odessa, a single mom with a similar penchant for toxic men; Seth, a detached artist who’s lack of commitment permeates every facet of life; Brian, who sets the bar for stability low, but whom Nina considers her most stable partner; and Aaron, a former classmate and aspiring filmmaker who lives with his parents, with whom Nina initially develops a creative relationship with—leaving her life as a writer in the middle of it all.

Told with acerbic wit, keen observation, and elements of dark humor, Gerard’s True Love is a timely tale of yearning for connection in a world that is fragmented by default.

Told with acerbic wit, keen observation, and elements of dark humor, Gerard’s True Love is a timely tale of yearning for connection in a world that is fragmented by default.

The Millions: I see pieces of myself in Nina. Did she come to you like that or did she arrive on the page fully formed from the get-go?

Sarah Gerard: She took some massaging. I went through a few different names and occupations, and at one point had given her a very cumbersome backstory. Hardest was landing on what her motivation is, moment-to-moment, and also long-term—and how those two things might be in conflict. The tone of the book was also difficult to land. For the first several drafts, Nina just had no sense of humor, probably because, ironically, she wasn’t being totally honest with the reader.

TM: How did the idea for True Love come to you?

SG: I was asking broad questions about what love is and how it operates, in my life and in the world. It’s both ambient and directed; a state of being and an action. It’s ecstatic and painful and joyful and crushing. Very often, we can’t seem to find love—or what my partner and I call “good love”—though we want it very badly. A character is a mode of inquiry, so I used Nina as a vehicle to explore how people might get in their own way, looking for love; where we learn to love; how we know love is present; and what love, or the desire for it, leads us to do. I was also, as the title might suggest, curious about the relationship of love and truth.

TM: Your previous novel, Binary Star, hones in on addiction and codependency, which are also, in some form, present in this book. Why did you want to continue your exploration of these themes?

SG: One definition of love that I offer in the book is that of an addiction. Another is a trance. In either case, it’s an altered state of seeing and sensing and understanding. In the book, I define trance as an inwardly directed, selectively focused attention, to the exclusion of all else. I was also thinking of love as a substance that could be just as easily used to manipulate and exploit and traffic in as a drug.

TM: Florida lit is a genre in and of itself. Your debut collection of essays, Sunshine State, I believe, stands at the helm alongside the work of Alissa Nutting and Kristen Arnett. What nod to Florida did you want to give by having your new book start there?

SG: Structurally, my intent was to divide the story into two parts. Florida is much slower and lazier than New York City, so there’s a tonal shift midway through the book when Nina and Seth leave. The world of the story becomes darker, in my mind, and more claustrophobic, threatening. The Florida setting is somewhat disturbing, yet edges toward absurd and provincial, whereas New York is dangerous and exploitative, as Nina experiences it. She’s also separated from her friends and her support network after she leaves Florida, so although the city seems to close in on her, it is also lonelier.

TM: I love the specific references to the neighborhoods in New York City, especially the bookshop where Nina works. I know you were a bookseller at two of NYC’s beloved indie bookstores. What other similarities do you share with Nina?

SG: I love independent bookstores. They really do the Lord’s work. I’ve worked at McNally Jackson Books and Books Are Magic, and would work at another bookstore in a heartbeat. There’s nothing better than talking about books all day, then spending half of your retail-wage paycheck on books because you get a staff discount and have been shopping at work. Seriously, though, bookselling has taught me so much about writing and publishing.

TM: I’m particularly intrigued by Nina’s friend Odessa. She offers this contrast, makes certain things about Nina stand out more. Was this your intention in writing her?

SG: Especially in a first-person narrative, the catalyst for character transformation has to originate outside of a character. Change comes about as a result of friction in the narrative. Nina and Odessa are very different people, but they have a long history, and know each other on a fundamental level. So, Odessa both offers a counterpoint to Nina, as well as a touchstone for who she is, on a base level, when she may feel as if she’s losing herself—or as when, as Odessa points out, she’s lying. Odessa also calls Nina out for her class privilege and her selfishness. A lot of characters call Nina out for various things. Ultimately, each one of them offers a window onto a very tangled situation.

TM: As someone who, at one point, could have been the brand ambassador of toxic relationships, I sometimes fear of stepping back into my old habits. Like, I have to consciously remember the emotional work I’ve done in years of therapy. Do you think we can become addicted to those types of relationships and, if so, do you think we can ever truly move beyond them without them haunting us?

SG: Toxic relationships are hurtful, and exist on a continuum of uncaring and manipulative behavior, ranging from microaggressions to violence. It haunts us because it hurts us. Unlearning it takes self-reflection, and practice acting with compassion, as well as setting boundaries. Forgiveness is also important, and that includes self-forgiveness.

TM: Nina’s mother is very much a presence in her life, even though her absence—especially when she constantly dodges her daughter’s attempts to visit her—is what mostly comprises that presence in Nina’s heart and mind. Do you think her relationship with her mother holds her back, maybe even influences her bad decisions?

SG: One of the questions I was asking in writing this book is where we learn to love. Early relationships are foundational, and patterns are very hard to break, especially when they’re deeply ingrained from a young age. Nina and her mother are more similar than she realizes. There is a lot of her mother in her desire to please, her martyrdom, her inability to take responsibility for the ripple-effects of trauma, her bossiness—just to start. Nina’s path to healing her relationship with her mother begins when she finally sets a boundary with her that she can hold.

TM: Has writing this book taught you anything about yourself?

SG: Everything I write teaches me about myself. It also teaches me about the world.

Bonus Links from Our Archive:

—Transforming Florida: On Sarah Gerard’s ‘Sunshine State’

—The Path to Destruction: On Sarah Gerard’s ‘Binary Star’