A mother of two used to dance at a Tampa-area club called Mermaids. She orgasmed while getting her lower back tattooed, she believes in the Illuminati, and claims to have been abducted by aliens. She believes the earth is hollow. She believes in psychics. You know her as Florida Woman, Florida Man’s less frequently but no less gleefully derided counterpart. To you and many others, these superficial details are not only funny, but further proof of Florida’s endemic, statewide wackiness. From a comfortable remove, you extrapolate. You link headlines into a constellation:

- Two Jailed in Tampon-Tossing Melee in Port St. Lucie

- Naked Man Accused of Home Break-In Just Wanted “Sesame Seeds For His Hamburger”

- Belching Shirtless Woman Says Deputy is “Sexiest Thing”

- Hubby Drove with Wife ON ROOF OF Sport Utility Vehicle

Instead of Orion immortalized for his hunting prowess, this constellation forms a fisherman shooting himself in the junk. As the police blotter rolls, the headlines stack, and now the national conversation around the Punchline State is more roast than dialogue. These days, only West Virginians can relate to the plight of Floridians. In the rest of the nation’s eyes, the welcome signs on both state lines might as well read, Abandon all class, ye who enter here.

But this cruel elision robs people of their humanity, and it ignores the conditions in which they exist. What’s funny about addiction, about spousal abuse? What is it about the addition of palm trees that makes misery comical? It’s telling that the butts of most “Florida Man” (or “Woman”) jokes are working class, strung out, or mentally ill, and that they’re set in a place ranked among the bottom half of all states in education, poverty rate, and mental health services. Sadness overcomes sunshine. Behind every failure lies a murdered dream.

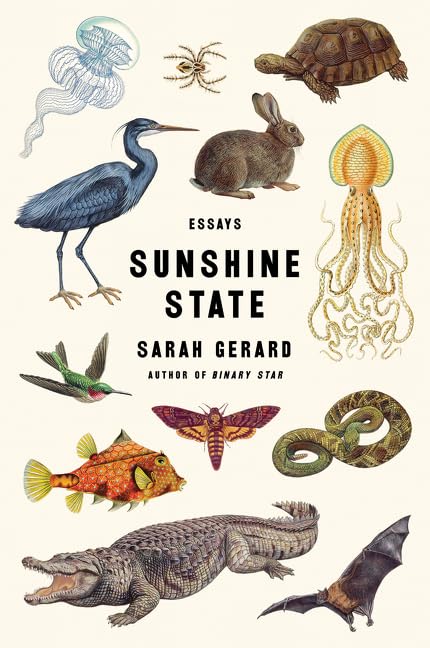

That Mermaids dancer, for instance, was once Sarah Gerard’s closest friend. She’s the subject of “BFF,” the first essay in Gerard’s outstanding new collection, Sunshine State. In a series of short, remembered vignettes, Gerard catalogs the times they shared – both good and bad – and how their lives collided, intertwined, and ultimately diverged. “You were the closest thing I had to a sister,” Gerard writes, recalling their intimacy the way an amputee might remember a lost limb.

There’s a sustained ache throughout, a sincere frustration with childhood naiveté, personal limitations and betrayal. “There was so much I didn’t know about you,” Gerard confesses, “and I’m angry with you for thinking that I did. I’m angry with myself for failing to see it.” Memories of her friend’s youthful quirkiness give way over time to Gerard’s recognition of the scars that shaped them. Recalling the friend’s unpredictability and mistakes, Gerard searches for cause, asking, “Were you mad at your father, who choked your mother while you watched when you were three?”

Or your then-boyfriend, who once swung the broad side of his shovel into your pelvis; who came home drunk one night and peed on you while you slept; who dragged you across your apartment by your hair; who, you once explained, you find sexy because he’s primal?

“BFF” sets a tone for the seven other essays in the collection, which work together to subvert the most common tropes about Florida’s antic madness. Instead they focus on humanizing the state’s inhabitants – inhabitants with hopes and dreams, who cope with systemic and visceral issues all too frequently omitted from national headlines. As the one who got away from the state when her friend could not, Gerard feels guilty. “You haunt me in my everyday,” she writes, simultaneously addressing her one-time friend, but perhaps also addressing her home state itself.

Gerard’s writing has been described as “unflinching,” but perhaps the better terms are “generous” and “patient.” Her patience is what gets her close enough to her subjects that she can round them out, exhibit their complexities, and her generosity is what keeps her from mocking them. “I searched for the proper way to respond,” Gerard writes at one point, in the midst of a conversation with a good-hearted man who’s nevertheless unwell, criminal, or some combination of the two. In Gerard’s hands, the people who would ordinarily be flattened into condescending headlines are given space to take fuller shape, and she’s able to pick at the scabs to probe the scars beneath.

In Sunshine State’s eight essays, Gerard covers her family’s years in the New Thought movement (“Mother-Father God”), her father’s interest in Amway (“Going Diamond”), her grandparents’s twilight years (“Rabbit”), and her drug-addled adolescence (“Records”). She embeds with a recovering addict working to help the homeless (“The Mayor of Williams Park”). She investigates allegations of grift in a bird sanctuary (“Sunshine State”), and she reflects on her life’s journey (“Before: An Inventory”). In that last one, built out of quick, diary-like observations written about the places she’s traveled, readers can tell Gerard’s getting close to Florida when the descriptions of lizards grow more frequent.

Throughout, Gerard’s essays traverse a complete spectrum of themes familiar to anyone who’s spent time in Florida – drugs, teenage boredom, nature, fraud, faith, and homelessness – but they also ground these themes within Florida quite subtly. Gerard’s focus is on the people, less so the place. Better still, her focus is on their states of mind, less explicitly on their state of residence. Those looking for beach walks, zaniness, and neon hijinks ought to look elsewhere, because in Sunshine State, Florida is cast in relief: she’s the recurrent rain in the essay on homelessness; the radiant sun scarring spots into the conservationist’s face; the memory of spurs stuck in a child’s heels; the “lizards on the porch (looking weathered).”

The conceit is powerful. Florida is a state in constant flux, at once being reclaimed by the sea as humans remake her in their own image. She shapes her inhabitants in ways they don’t consciously recognize, and only after leaving do they realize what’s happened. Awakening to a thunderstorm, Gerard writes that morning storms in Florida are “a special kind of sign, a reminder that you’re trespassing on Mother Nature’s turf–that everything you know could be washed away in an instant.” Later, in “Mother-Father God,” Gerard remembers her father’s interest in New Thought literature, especially the work of Ernest Holmes, who taught that “people are at all times engaged in their own transformations.” At the start of “Records,” a pitch-perfect rendering of intense, suburban teenage boredom, Gerard refers to the whole period as her “year of living dangerously.” It’s a nod to the risks she takes, but it’s also acknowledgment that the year ended, that a transformation took place – that it’s been taking place the whole time.

Sunshine State is a welcome addition to the Florida canon, not only because it vivifies the state’s cartoonish image, but also because it demonstrates how continuous the act of transformation can be, and how being engaged with something is not the same as being happy about it.