My reading choices this year were far more focused than they have ever been—rage has a way of focusing you, as does getting the Grace Paley Teaching Fellowship at The New School. I spent most of the year reading in preparation for my course, “Traditions in Non-Western Feminism,” and began by breaking up the regions and peoples and continents that I wanted to explore: East Asia, Africa, South America, the Indian subcontinent, the indigenous peoples of the Americas, and so on. Then I started reading:

So Long a Letter by Mariama Bâ; “Forgive me once again if I have re-opened your wound. Mine continues to bleed.”

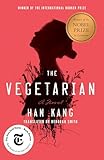

The Vegetarian by Han Kang; “She laughed. Faintly, as if there were nothing she wouldn’t do, as if limits and boundaries no longer held any meaning for her. Or else, as if in quiet mockery.”

The Vegetarian by Han Kang; “She laughed. Faintly, as if there were nothing she wouldn’t do, as if limits and boundaries no longer held any meaning for her. Or else, as if in quiet mockery.”

Tell Me How It Ends by Valeria Luiselli; “In the United States, to stay is an end in itself and not a means: to stay is the founding myth of this society.”

Blood of the Dawn by Claudia Salazar Jiménez; “Made a battlefield, your body has become acutely vulnerable.”

Women Without Men by Shahrnush Parsipur; “In the spring her entire body was covered with new leaves. It was a good spring. She learned the water’s song.”

Women Without Men by Shahrnush Parsipur; “In the spring her entire body was covered with new leaves. It was a good spring. She learned the water’s song.”

In choosing these books for the course, I had thought to show my students (and myself) how the struggles of women in the non-Western world are unique, unexplored, silenced. We read, discussed, dissected. We asked questions of each other. Has there ever been an instance in Western literature of a woman turning into a tree? Why don’t any societies exist (outside of some regions of Tibet) in which a woman takes multiple husbands? How would one take the Terms & Conditions to which we agree whenever we sign a contract and apply them to the body, the boundary of a woman? How many orifices does a woman have?

These questions and more swirled around the room. We debated and we laughed and we cried and we shouted and sometimes we grew quiet. Quiet, quiet. If you say this word softly enough, the wind rushes back into the room, and seas surge, and you can hear the birds. You can hear the sigh of a woman who is not even in the room. Who is on a far continent. Or is she?

Toward the end of the semester, literature did what literature does. Our hearts began to beat in tune. And then we began to understand that yes, each story was unique, perhaps even unexplored, but not one women, not anywhere, was silent. They wrote landays, they pierced their bodies, they wore their abayas inside out. Silence is capitulation; it refuses to be an option for many.

As conversation deepened, as awareness grew, here is what else I realized: it had been so very naïve of me, that breaking up into regions, peoples, continents. It had been so very fustian. Every day gone by, every book read, made me see that the distinctions I had made were arbitrary, elusive. There was only the human journey, the one where we all cry out with mouths full of dirt, the one where we all wear laurels for a crown. Why the segregation? There was only us. As the astronaut Sultan bin Salman bin Abdulaziz Al Saud said about his time in space, “The first day or so we all pointed to our countries. The third or fourth day we were pointing to our continents. By the fifth day, we were aware of only one Earth.”

More from A Year in Reading 2018

Don’t miss: A Year in Reading 2017, 2016, 2015, 2014, 2013, 2012, 2011, 2010, 2009, 2008, 2007, 2006, 2005