The mind is a terrible thing, easily manipulated, blinkered, and pulled in a particular direction. History is no help; recounting the events of brave or stupid people doing brave or stupid things makes us mad and self-righteous, but we are resistant to deviations from our preferred way of reading the past. Even after we’ve figured out history—or think we’ve figured it out—it seems impossible for everyone else to get the narrative right.

So maybe we should be getting all geared up for this “future” about which everyone’s talking. Thanks to tech geniuses and the intellectuals they love to promote, we can expect great things for our flawed minds: expanded memory, a more rigorous use of the synapses, and ideas uploaded directly to the brain with no worry about the consequences. Consider Yuval Noah Harari’s Homo Deus, wherein a torrent of anecdotes serves to refashion humanity into data processing machines, with god-status just around the corner. The downsides involve the coming inequality in pure physical and cognitive ability between the rich and poor, which will only exacerbate their material divide. This isn’t evidently much of a downside for Harari fans like Bill Gates and Mark Zuckerberg, both richer than God Himself.

So maybe we should be getting all geared up for this “future” about which everyone’s talking. Thanks to tech geniuses and the intellectuals they love to promote, we can expect great things for our flawed minds: expanded memory, a more rigorous use of the synapses, and ideas uploaded directly to the brain with no worry about the consequences. Consider Yuval Noah Harari’s Homo Deus, wherein a torrent of anecdotes serves to refashion humanity into data processing machines, with god-status just around the corner. The downsides involve the coming inequality in pure physical and cognitive ability between the rich and poor, which will only exacerbate their material divide. This isn’t evidently much of a downside for Harari fans like Bill Gates and Mark Zuckerberg, both richer than God Himself.

Harari’s future, bright for those at the top, is countered in a recent book of creative revisionism: John Higgs’s Stranger Than We Can Imagine: Making Sense of the Twentieth Century. The book uses the concept of the omphalos, a religious and symbolic navel, or center, of the universe (think Delphi to the ancient Greeks or Graceland to Elvis fans), to discuss how the 20th century radically changed the way we think and act. The West’s omphaloi, once Church, Empire, and Victorian Tradition, are now things like the Universe, Democracy, and the Self.

Harari’s future, bright for those at the top, is countered in a recent book of creative revisionism: John Higgs’s Stranger Than We Can Imagine: Making Sense of the Twentieth Century. The book uses the concept of the omphalos, a religious and symbolic navel, or center, of the universe (think Delphi to the ancient Greeks or Graceland to Elvis fans), to discuss how the 20th century radically changed the way we think and act. The West’s omphaloi, once Church, Empire, and Victorian Tradition, are now things like the Universe, Democracy, and the Self.

These books differ in their respective outlooks—Higgs tells us about a past that’s set us up for failure, whereas Harari relays an exciting, godlike future—but they both have one thing in common: they refer to the story of Marcel Duchamp’s “Fountain,” the symbolic, radical departure for the art world.

How does Harari recount it?

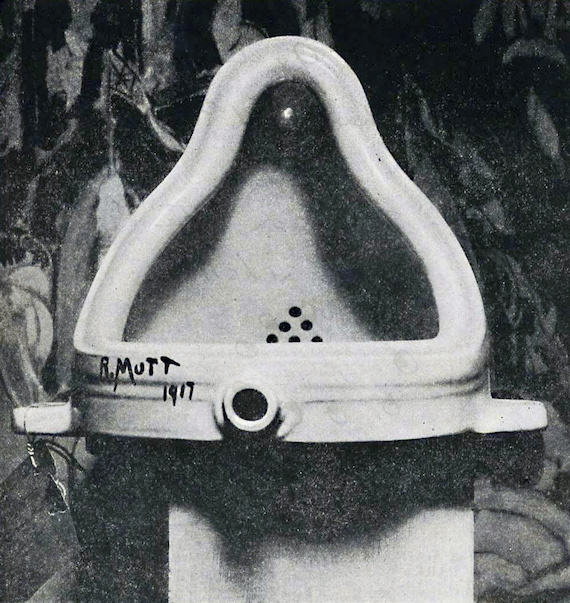

In 1917, Marcel Duchamp took an ordinary mass-produced urinal, named it Fountain, signed his name at the bottom, declared it a work of art and placed it in a Paris museum.

It’s a short statement rife with inaccuracies. It’s probably how Harari remembered the story before dashing it off; it’s probably how his editors remembered it, never considering to quickly glance at a reliable source for basic validation; and it’s probably how many of his eager readers remember it, too, among them ambitious billionaires quickly gaining the abilities to literally shape our minds. But that’s not how the story goes. Duchamp, a Frenchman who decamped to America during World War I, submitted “Fountain” to an art show in New York (not Paris); he signed a name (R. Mutt), not his name on the piece; and he didn’t place it anywhere—this wasn’t some proto-Banksy stunt. It was rejected from an art show, despite the show’s rule that any submissions would be accepted and the fact that Duchamp himself was on the board of the society throwing the show. The original piece was then lost, tossed out with the garbage.

Duchamp also didn’t create a new American movement overnight. A magazine snapshot, some ardent Dadaist clamoring, and a new generation of artists in the ’50s and ’60s turned it into a groundbreaking work of art. The story surrounding Duchamp’s piece is what gave it its radical heft, but this story still makes it Duchamp’s piece.

More transgressive to the modernist narrative, but probably more correct, is Higgs’s version of the story:

Duchamp’s most famous readymade [an everyday object presented as a piece of art] was called ‘Fountain.’ It was a urinal, which was turned on its side and submitted to a 1917 exhibition at the Society of Independent Artists, New York, under the name of a fictitious artist called Richard Mutt. The exhibition was aimed to display every work of art that was submitted, so by sending them a urinal Duchamp was challenging them to agree that it was a work of art. This they declined to do. What happened to it is unclear, but it was not included in the show and it seems likely that it was thrown away in the trash. Duchamp resigned from the board in protest, and ‘Fountain”s rejection overshadowed the rest of the exhibition.

This seems to line up with what actually happened. But Higgs continues to expound upon the background to ‘Fountain:’ he concludes that it probably wasn’t even Duchamp’s work. A Bohemian by the name of Baroness Elsa von Freytag-Loringhoven probably sent it to her friend Duchamp, who then took credit for the work. A letter Duchamp sent to his sister, Suzanne, seems to back this version of events: “One of my female friends, who had adopted the male pseudonym, Richard Mutt, sent me a porcelain urinal as a sculpture.”

Let it also be said that Baroness Elsa von Freytag-Loringhoven was amazing, and it’s almost criminal how she’s been left out of the Dadaist story. Even if she wasn’t, indeed, the real Fountainhead, she seemed to live the movement to a far greater degree than Duchamp ever did. An actual baroness by marriage, she was a performance artist, poet, friend, and subject of artists like Duchamp and Man Ray, with a penchant for scatological humor and creating art out of rubbish (which may mean the person responsible for tossing ‘Fountain’ wasn’t far off the mark).

Duchamp was a forward-thinker, sure. He recognized ‘Fountain’ as part of what Higgs’s refers to as modernity’s “persistent attempts to destroy frames of reference,” in line with the omphalos-shifting revolutions of World War I, popular democracy, and Albert Einstein’s Theory of Relativity. But he also, maybe, knew he could get away with taking credit for history; he knew how people like Harari would casually refer to his version of events as a service of some higher human goal. It wasn’t even the piece, in and of itself, that was groundbreaking—it was the narrative pushed to popularize it. Freytag-Loringhoven was the truer Dadaist, but Duchamp the better marketer.

The way Harari tells of ‘Fountain’ fits exactly into the narrative Homo Deus parlays: modernist liberalism—along with the smashing of the omphalos and the new focus on subjective experiences and definitions—invaded our conscious as quickly as one nation invades another. A cursory look at Google can prove Harari’s account isn’t accurate, but what’s worse is the tone. It’s glib. It’s right in line with how things should be in Harari’s human histories. We just did dumb things, like organize as a society, until a wise person broke our routine. Eventually, a smart person will break our brains, and all for the better.

Higgs isn’t so sure. Yes, the omphalos was shattered by modernism, not unlike Harari’s version of events, but what makes the narrative messier is the power structure. It’s this structure that elevates Duchamp, all the while forgetting the woman who most likely made the piece. Forgetting that he admitted that a woman made it in the first place.

Harari is kind of like Duchamp, in that he’s an educated charlatan selling a particular fantasy. It’s no wonder that wealthy icons like Bill Gates and Mark Zuckerberg signaled his first book, Sapiens: A Brief History of Humankind, as a favorite: it ends with man becoming God through the power of technology, a theme continued in his sequel. Our minds will be enhanced with their technology, and we will accept it as simply as the war-battered Parisian public accepted Duchamp’s ‘Fountain.’

Harari is kind of like Duchamp, in that he’s an educated charlatan selling a particular fantasy. It’s no wonder that wealthy icons like Bill Gates and Mark Zuckerberg signaled his first book, Sapiens: A Brief History of Humankind, as a favorite: it ends with man becoming God through the power of technology, a theme continued in his sequel. Our minds will be enhanced with their technology, and we will accept it as simply as the war-battered Parisian public accepted Duchamp’s ‘Fountain.’

But how will we get our stories straight when the powers that be won’t do it for us? If Harari were left in charge of uploading the bit about Duchamp into my new, improved God-Man brain (should I be able to afford such a luxury), there wouldn’t be any mention of Baroness Elsa von Freytag-Loringhoven. Even if popular history is correct and Duchamp did make the piece, there still wouldn’t be any nuance to ‘Fountain”s history, no what-could-have-beens, no debate about its real creators, thinkers, and influencers. A radical piece of art would be turned into an explanation for why we love social media, and why our brains are nothing more than computers that need to be upgraded, enhanced and molded.

It almost feels like we’re in a race between technology and the fair narrative. As the focus changes, and marginalized people take control their own stories, it’s possible we’ll see a change in the tenor of popular history. The stories of marginalized won’t be seen as “revisionist” history, but simply as history. That is, if they can beat Silicon Valley to our brains.

Image Credit: Wikimedia Commons.